The two stood side by side—one in the shadow of the other—at the corner of West 7th and Taylor streets.

One was imposing: eighteen stories tall and built of steel and brick. The other was less imposing: six feet tall only when standing on his pinewood fruit crate, with a disarming grin, a twisted foot, and a speech impediment. But both were Fort Worth landmarks, and after standing side by side for forty-four years the two landmarks fell within twenty months of each other.

The imposing landmark was the Worth Hotel, which opened on September 24, 1927.

The less-imposing landmark was Monroe Odom, whom Star-Telegram publisher and civic booster Amon Carter selected to cut the ribbon at the hotel’s opening ceremony.

Who was Monroe Odom?

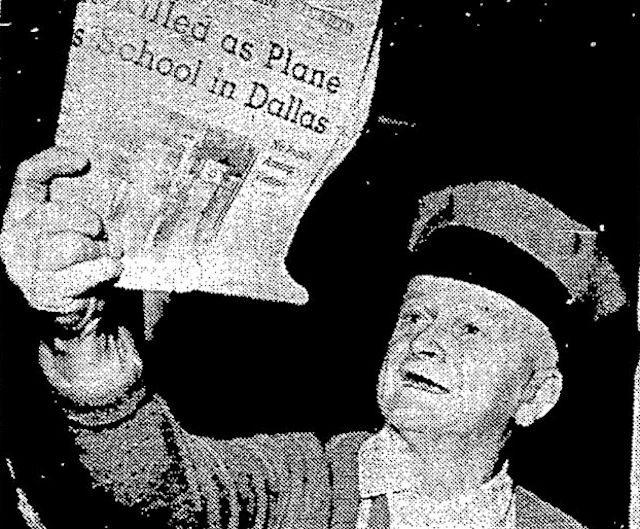

Think back to a time before the newspaper was delivered to your home digitally by a virtual paperboy: the Internet. Think back, even, to a time before the newspaper was dispensed by a vending machine. Early in the twentieth century, when child labor was common and largely unregulated, many people bought their daily newspaper from newsies. Newsies were boys, some of them less than ten years old, who hawked newspapers on sidewalks and street corners, at train stations (and on the trains themselves), and at other locations that had heavy foot traffic. Newsies were part town crier, part carnival barker. They sold newspapers by selling the news therein: “Read all about it,” a newsie might cry out as he touted a headline he had selected to boost sales among passersby, all the while holding up a copy of the latest edition:

“7 Executed by Gang Firing Squad” in Chicago on Valentine’s Day in 1929.

“Japan Declares War on U.S.” on December 8, 1941.

“Surrender Articles Are Signed” on September 2, 1945.

“Surrender Articles Are Signed” on September 2, 1945.

And, closer to home, “18-Foot Python Escapes at Zoo” on September 18, 1954.

For forty-four years Monroe Odom was the king of Fort Worth newsies. From the day he cut that ribbon at the Worth Hotel on September 24, 1927 until the night he died in front of the hotel next to his pinewood fruit crate, Monroe Odom sold the news for twelve hours every day through rain and shine, through good news and bad, through Depression and Prohibition, through two world wars, two Will Rogerses, and two Amon Carters.

Monroe Odom was born in Cleburne in 1902, but he and his mother and sisters soon moved to Fort Worth. Perhaps the most complete account of Monroe Odom’s life in Fort Worth is in Jerry Flemmons’s biography Amon: The Life of Amon Carter, Sr. of Texas. Flemmons writes that Monroe first came to Amon Carter’s attention when Monroe was either five or ten years old. Let’s be conservative: age ten (1912). By 1912 Carter and five other businessmen had taken control of the Fort Worth Telegram and had rebranded it: Star-Telegram. Carter was business manager and secretary, not yet publisher. The newspaper was located at 815 Throckmorton Street. Each day as the latest edition of the Star-Telegram began to roll off the presses, Flemmons writes, newsies gathered at 815 Throckmorton to get newspapers to sell. There was no “Oh, no. I insist: You go first” politeness among the boys. It was every newsie for himself in a frenzied scramble for newspapers. One of the smallest boys, who walked with a limp and talked with slurred speech, held his own amid the flying elbows and expletives.

Monroe Odom was born in Cleburne in 1902, but he and his mother and sisters soon moved to Fort Worth. Perhaps the most complete account of Monroe Odom’s life in Fort Worth is in Jerry Flemmons’s biography Amon: The Life of Amon Carter, Sr. of Texas. Flemmons writes that Monroe first came to Amon Carter’s attention when Monroe was either five or ten years old. Let’s be conservative: age ten (1912). By 1912 Carter and five other businessmen had taken control of the Fort Worth Telegram and had rebranded it: Star-Telegram. Carter was business manager and secretary, not yet publisher. The newspaper was located at 815 Throckmorton Street. Each day as the latest edition of the Star-Telegram began to roll off the presses, Flemmons writes, newsies gathered at 815 Throckmorton to get newspapers to sell. There was no “Oh, no. I insist: You go first” politeness among the boys. It was every newsie for himself in a frenzied scramble for newspapers. One of the smallest boys, who walked with a limp and talked with slurred speech, held his own amid the flying elbows and expletives.

One day Amon Carter witnessed Monroe’s pint-sized pluck.

“Here,” Carter said, handing Monroe twenty newspapers. “Sell these in an hour, and you have a job.” Monroe hurried to the nearest saloon with his newspapers. Only too aware of his physical challenges, Monroe reasoned that men would buy from a small boy with a limp and a speech impediment. Fifteen minutes later Monroe, silver dollars jingling in his pocket, reported back to Carter. For twenty newspapers with a total retail value of forty cents, Monroe had collected eleven dollars. Carter, who had known poverty as a child in Bowie, identified with “his” newsies. Carter also was a businessman who admired moxie. And rewarded it. He hired Monroe on the spot.

It was the last job interview Monroe Odom would ever have.

Monroe, like many other newsies, worked to help support his family. In the beginning, as he learned the trade and rose in seniority in the ragtag fraternity of newsies, Monroe was a rover: He had no territory of his own. But eventually he claimed—and defended, sometimes physically—his own street corner. And then a better street corner.

Then came 1927. Amon Carter was now president and publisher of the Star-Telegram. The newspaper company was now located at 400 West 7th Street. And Monroe Odom was now twenty-five years old—old for a newsie. But with that year came the ultimate newsie territory: When the Worth Hotel opened across Taylor Street from the Star-Telegram building, Amon Carter bestowed upon Monroe territory at the hotel’s front door. Carter even let Monroe cut the ribbon at the opening.

That ribbon-cutting ceremony would be, in effect, a wedding between a man and a building: For the next forty-four years if you walked past the Worth Hotel, you walked past Monroe Odom.

With the new hotel open for business, on the sidewalk near the hotel’s front door Monroe positioned a pinewood fruit crate on which to stand to increase his visibility—and his audibility. His pinewood podium in place, voila: His new retail outlet was fully furnished, and he, like the Worth Hotel, was open for business.

Monroe’s location was indeed prime newsie territory: Within a block of his fruit crate along West 7th Street were—in addition to the Worth Hotel and Theater—the Fort Worth Club Building (with Fakes Department Store on the ground floor), Star-Telegram building, the Neil P. Anderson Building, and, by 1930, the Hollywood Theater and Texas Electric Service Company.

Monroe’s customers, in addition to shoppers and showgoers and hotel guests, included bankers, oilmen, civic leaders. Most were pedestrians. But some were passengers in chauffeur-driven limousines that pulled up to Monroe’s curb. Good tippers. Most of them had home delivery of the Star-Telegram, but Monroe knew the way to their heart—and their wallet.

Beeman Fisher, president of nearby Texas Electric Service Company, began paying Monroe one dollar a week. Eventually Fisher was forking over five dollars a week even though the price of the newspaper had not increased.

In addition, at Christmas Fisher gave Monroe a bonus. Monroe also received a Christmas bonus from the Star-Telegram, although he technically was a freelancer, not an employee.

But perhaps the best measure of Monroe’s salesmanship was his ability to sell a newspaper to the people least likely to want to buy one: Star-Telegram employees.

One day Monroe was in the Worth Hotel coffee shop when a new reporter walked in.

“Paper, mister?” Monroe asked.

”I work for the Star-Telegram,” the reporter explained.

“So what?” Monroe asked.

Some days later the reporter wrote a human interest story about a lost boy. At lunch Monroe came to the reporter’s table in the coffee shop and complimented him. “Kids sell newspapers,” Monroe said. ”You see a copy yet?”

“No. Not yet.”

Monroe handed the reporter a newspaper with the story about the lost boy. The reporter had no small change. He handed Monroe a half-dollar. Monroe shuffled out, no change given. The reporter had been “Monroed.”

Flemmons writes that most every editor and reporter was Monroed at one time or another. It was a verb meaning that Monroe had sold them one of their own newspapers. And with a markup.

Amon Carter himself seldom left the Star-Telegram building without the latest edition in a suit pocket. Nonetheless he bought a copy from Monroe each time he passed on his way to the Fort Worth Club. He gave Monroe a dollar per copy.

Monroe’s rating of the news value of a story was based on his sales. Monroe knew that mayhem, not mundane, sells newspapers. “Train wrecks and plane crashes,” Monroe said. Star-Telegram editors called that the “Monroe Doctrine.”

Star-Telegram editors learned to avoid Monroe on a slow news day. Once a major federal official was fired, and the story ran for days as a board of inquiry investigated the firing.

Monroe collared an editor on the sidewalk: “This Washington stir was real good the first day,” Monroe said, “but the probe stuff is getting thin. Let it go with something else tomorrow.”

Monroe sold newspapers to presidents Roosevelt, Truman, and Eisenhower and to several Texas governors. For example, before John Connally became governor he lived in Fort Worth. When the newly elected Governor Connally returned to town he stayed at the Worth Hotel, where Monroe handed him a newspaper and grinned, “First one’s free, John.”

Wearing an ink-smeared apron with change pockets and, in his later years, a cap with a plastic bill, Monroe addressed them all—the meek and the mighty—by their first name. And they returned the familiarity. To all of Fort Worth the town’s best-known newsboy was just “Monroe.”

Doing business at an upscale hotel and a theater, Monroe also had as customers many celebrities who visited Fort Worth. Clara Bow was an early customer. In 1940 Gary Cooper came to town for the premiere of The Westerner. Amon Carter introduced Cooper to Monroe. As the time for the movie screening neared, Cooper’s publicity agents panicked because they could not find the star of the movie. They finally found Cooper in the Worth Hotel coffee shop—talking to Monroe.

“Don’t go away,” Cooper said to Monroe as Cooper’s publicity agents pulled him out of the coffee shop. “I’ll be right back.”

Many movie stars visited Fort Worth during World War II as part of war bond rally troupes. That’s when Barbara Stanwyck said to Monroe: “Spencer Tracy said to tell you ‘hello.’”

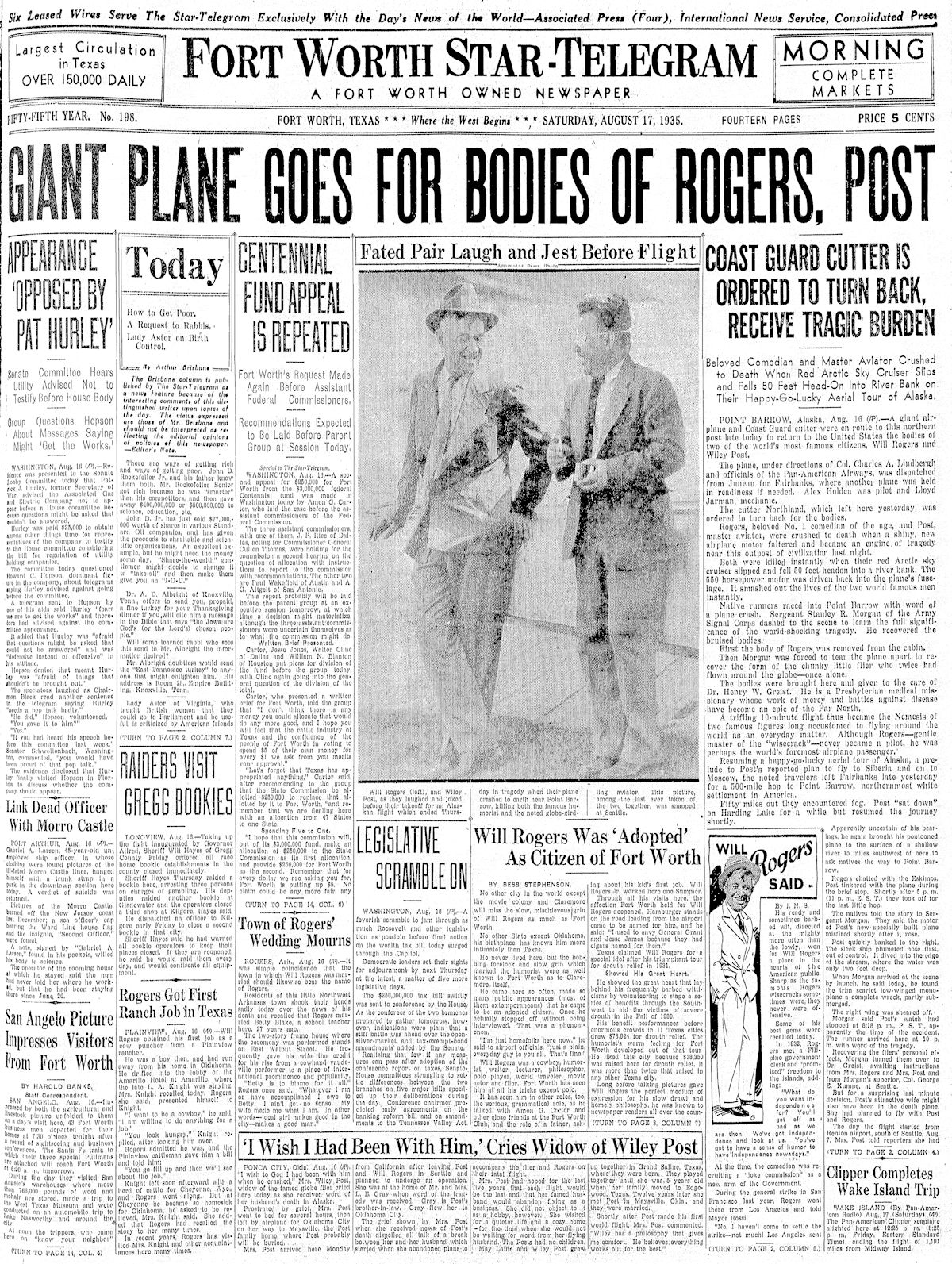

But humorist Will Rogers was Monroe’s favorite celebrity. Rogers, a friend of Amon Carter, stayed in Carter’s suite at the Fort Worth Club adjacent to the Worth Hotel.

Rogers gave Monroe the most money Monroe ever received for a single newspaper: “It was Christmas,” Monroe recalled. “Will handed me twenty dollars, he talked to me a little and then went on. Old Will was really a good man.”

When Rogers was staying at the Fort Worth Club, each day Monroe would take him a newspaper. One day Rogers invited Monroe to stay and have dinner: filet mignon.

After dinner, Flemmons writes, Monroe thanked Rogers for the meal and added, “Wish you’d tell ’em a little more well done next time, Will.”

Rogers laughed. “Okay, Monroe.”

Star-Telegram entertainment columnist Elston Brooks, who, like Monroe, by a young age had become a member of the Star-Telegram “family,” wrote about the time magician Harry Blackstone met his match in Monroe Odom.

Star-Telegram entertainment columnist Elston Brooks, who, like Monroe, by a young age had become a member of the Star-Telegram “family,” wrote about the time magician Harry Blackstone met his match in Monroe Odom.

Blackstone was performing at the Worth Theater, which presented both live entertainment and motion pictures. Monroe never needed a ticket at the Worth Theater. He’d just walk in between editions of the Star-Telegram. He watched Blackstone’s act several times. During each act Blackstone called for a volunteer from the audience to come onto the stage and nail Blackstone into a box from which he would escape. Night after night Monroe watched from the back of the theater as an audience volunteer—using hammer and nails supplied by Blackstone—sealed Blackstone in the box. Then the curtain was drawn. The pit orchestra played the “escape music.” When the curtain opened moments later, there stood the emancipated Blackstone.

Then came the final performance on Blackstone’s final night. A volunteer from the audience was called for. That was Monroe’s cue. He shuffled down the aisle, his apron pockets filled not with change but with nails the size of spikes. He carried a hammer in one hand.

As Blackstone’s frustrated aides watched and wrung their hands, Monroe tattooed the lid of the box with the huge nails on all four sides. Then he drove in a nail beside each of the first round of nails and bent the second nails over the first nails. Blackstone, Brooks wrote, was virtually welded into the box. Billy Muth, a member of the pit orchestra (and Worth Theater organist), recalled that as Monroe hammered, Muth could hear Blackstone muttering inside the box: “What’s going on?”

When Monroe was satisfied with his carpentry he stepped back and watched as the curtain closed and the orchestra played the escape music.

“We played the music bridge three times,” Muth recalled. “Every time the curtain would open, the box would still be there—and I could hear Blackstone cussing inside.”

On the fourth curtain pull, the audience saw a standby, dressed like Blackstone for just such emergencies, standing at the box. The Blackstone doppelganger took a quick—and face-concealing—bow and left the stage.

The box had to be destroyed to free Blackstone.

Long before Blackstone was freed, Monroe had made his escape: He was back outside on his pinewood podium selling the news of the day.

Monroe read each new edition of the newspaper to know the best selling points of his ever-changing product. Often Monroe “yelled” the banner story on page 1, but sometimes he yelled an inside story.

“Sometimes some guy will try to tell me the story I’m yelling is not in the paper,” Monroe once said. “When that happens, I just thumb to the page and show it to him.”

But Monroe’s motto was “Don’t cross your customers. Be friendly, nice, and they come back to you. I haven’t made much money on this job, but I’ve made a million friends.”

Sometimes Monroe tailored his “yell” to the customer. For example, if he saw a banker approaching, he touted a headline about interest rates. If he saw an oilman approaching, he touted a headline about a wildcat strike in west Texas.

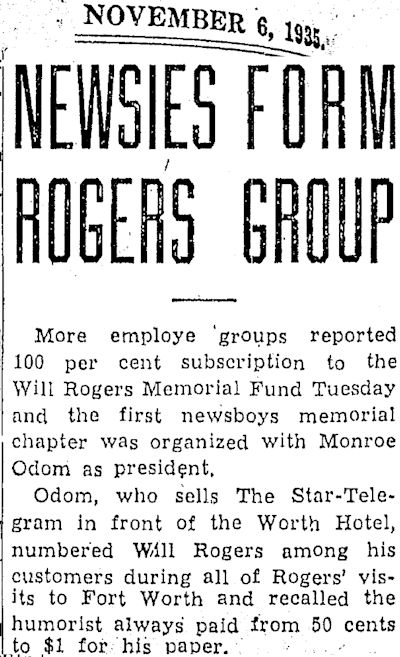

Sometimes the news hit close to home for Monroe. In 1935 came news that must have caused a catch in Monroe’s voice as he yelled the headline: His patron Will Rogers had been killed.

Sometimes the news hit close to home for Monroe. In 1935 came news that must have caused a catch in Monroe’s voice as he yelled the headline: His patron Will Rogers had been killed.

When local newsies formed a memorial chapter to honor Rogers, Monroe was president.

When local newsies formed a memorial chapter to honor Rogers, Monroe was president.

A year later Will Rogers Jr. came to town to attend the Frontier Centennial. The Star-Telegram report said Rogers Jr. “had his first newspaper experience on The Star-Telegram” as an ad salesman. “As Rogers went into the Fort Worth Club, where he is the guest of Amon Carter, he recognized Monroe Odom, newsboy, whom his father often spoke to by name on his many visits here. And, like father, like son, young Rogers bought one.”

A year later Will Rogers Jr. came to town to attend the Frontier Centennial. The Star-Telegram report said Rogers Jr. “had his first newspaper experience on The Star-Telegram” as an ad salesman. “As Rogers went into the Fort Worth Club, where he is the guest of Amon Carter, he recognized Monroe Odom, newsboy, whom his father often spoke to by name on his many visits here. And, like father, like son, young Rogers bought one.”

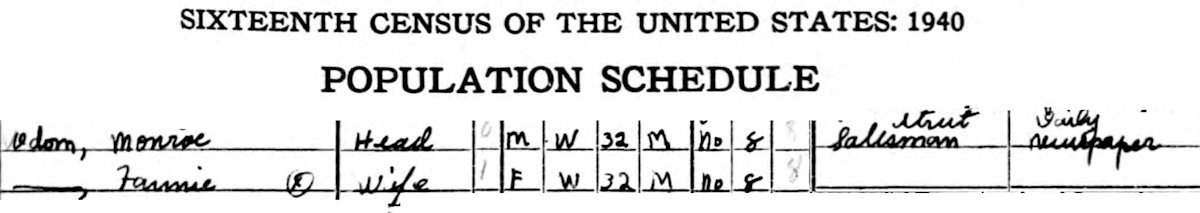

At some point Monroe married. In 1940 “daily newspaper street salesman” Monroe and wife Fannie lived in a small house on James Avenue. Today that house survives, sandwiched between the seminary and Rosemont Middle School.

At some point Monroe married. In 1940 “daily newspaper street salesman” Monroe and wife Fannie lived in a small house on James Avenue. Today that house survives, sandwiched between the seminary and Rosemont Middle School.

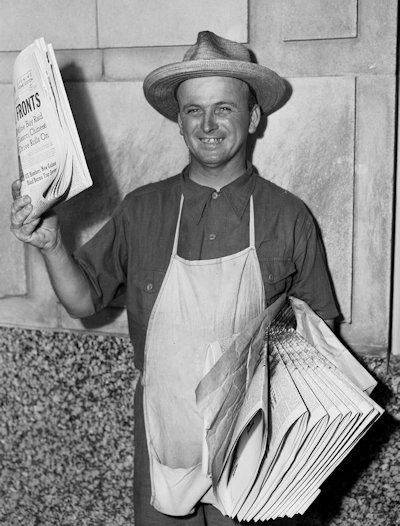

Monroe in 1942. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

Monroe in 1942. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

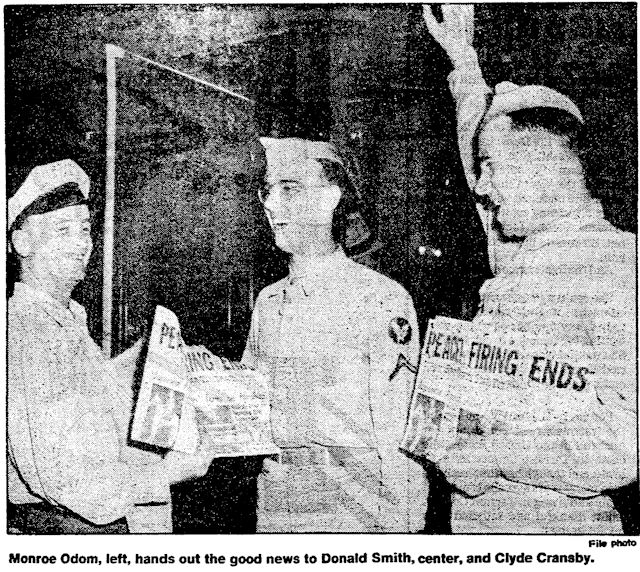

Monroe selling newspapers to soldiers on V-J day in 1945.

Monroe selling newspapers to soldiers on V-J day in 1945.

Monroe selling a copy of the Star-Telegram issue that commemorated Fort Worth’s centennial in 1949 to resident John J. Ray, age 104.

Monroe selling a copy of the Star-Telegram issue that commemorated Fort Worth’s centennial in 1949 to resident John J. Ray, age 104.

Then, in 1955, again came news that must have caused a catch in Monroe’s voice as he yelled the headline: His benefactor, Amon Carter, was dead. Carter in his will left money to his widow and children, his hometown of Bowie, the Fort Worth Club, Fort Worth police and firemen’s associations, Amon Carter Museum of Western Art, his physicians, his attorneys, his chauffeurs. And Monroe Odom.

Then, in 1955, again came news that must have caused a catch in Monroe’s voice as he yelled the headline: His benefactor, Amon Carter, was dead. Carter in his will left money to his widow and children, his hometown of Bowie, the Fort Worth Club, Fort Worth police and firemen’s associations, Amon Carter Museum of Western Art, his physicians, his attorneys, his chauffeurs. And Monroe Odom.

Flemmons writes that when Amon Carter Jr. was a teenager, Senior put Junior under Monroe’s mentorship to sell newspapers. “You might as well begin at the top,” Carter Sr. said. After Senior died Junior became publisher. Soon after Junior’s ascension, Monroe went to see his former protege. “I just wanted you to know I plan to go on selling the Star-Telegram.” Flemmons writes: “Amon Junior knew the empire would not crumble.”

In this photo of 1970 perhaps Amon Junior and Monroe were restaging the days when Junior as a teenager helped Monroe sell newspapers.

In this photo of 1970 perhaps Amon Junior and Monroe were restaging the days when Junior as a teenager helped Monroe sell newspapers.

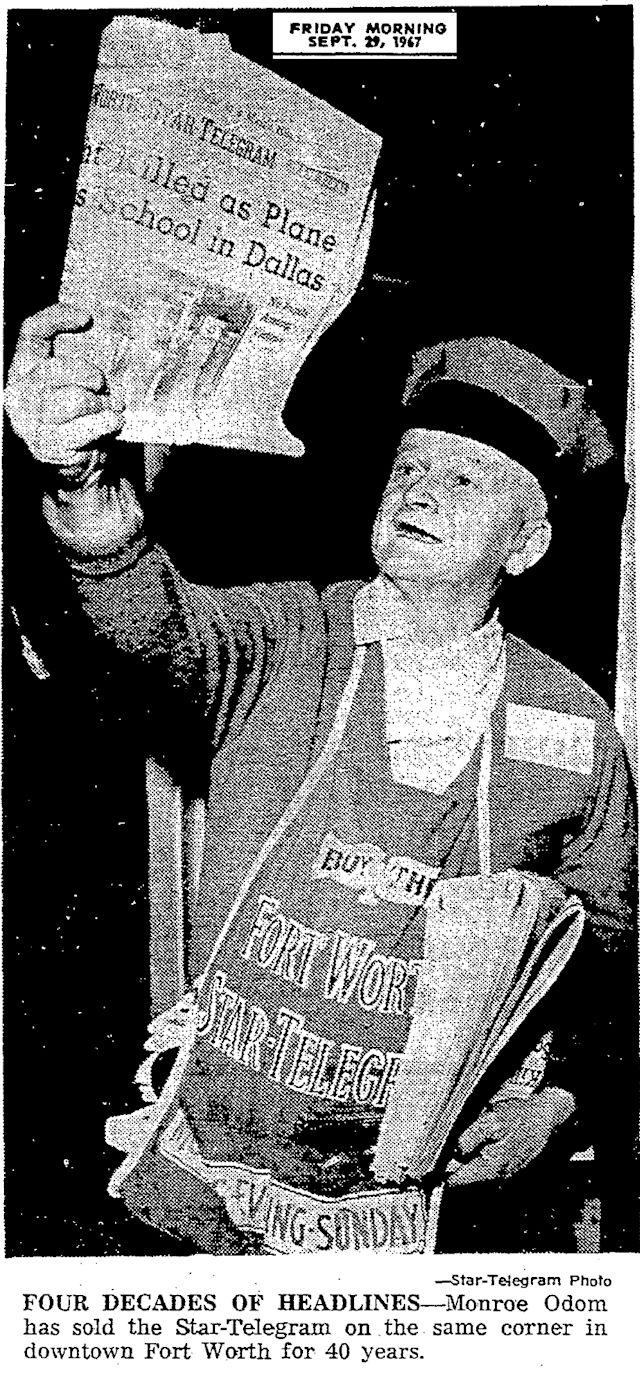

Monroe was interviewed by the Star-Telegram in 1967 when the Worth Hotel and Monroe celebrated their fortieth anniversary. He wore a badge reading “Life begins at 40.”

Monroe was interviewed by the Star-Telegram in 1967 when the Worth Hotel and Monroe celebrated their fortieth anniversary. He wore a badge reading “Life begins at 40.”

In that interview Monroe recalled the hard times of the Depression. “We sold newspapers for a cent each. Then it went to two cents in 1934-35, then to three cents and five cents about the start of World War II.”

Newspaper vendors don’t “holler anymore,” Monroe told the reporter. “People nowdays don’t like to be bothered: I let them know I’m here, but I don’t holler. Headlines sell the papers.”

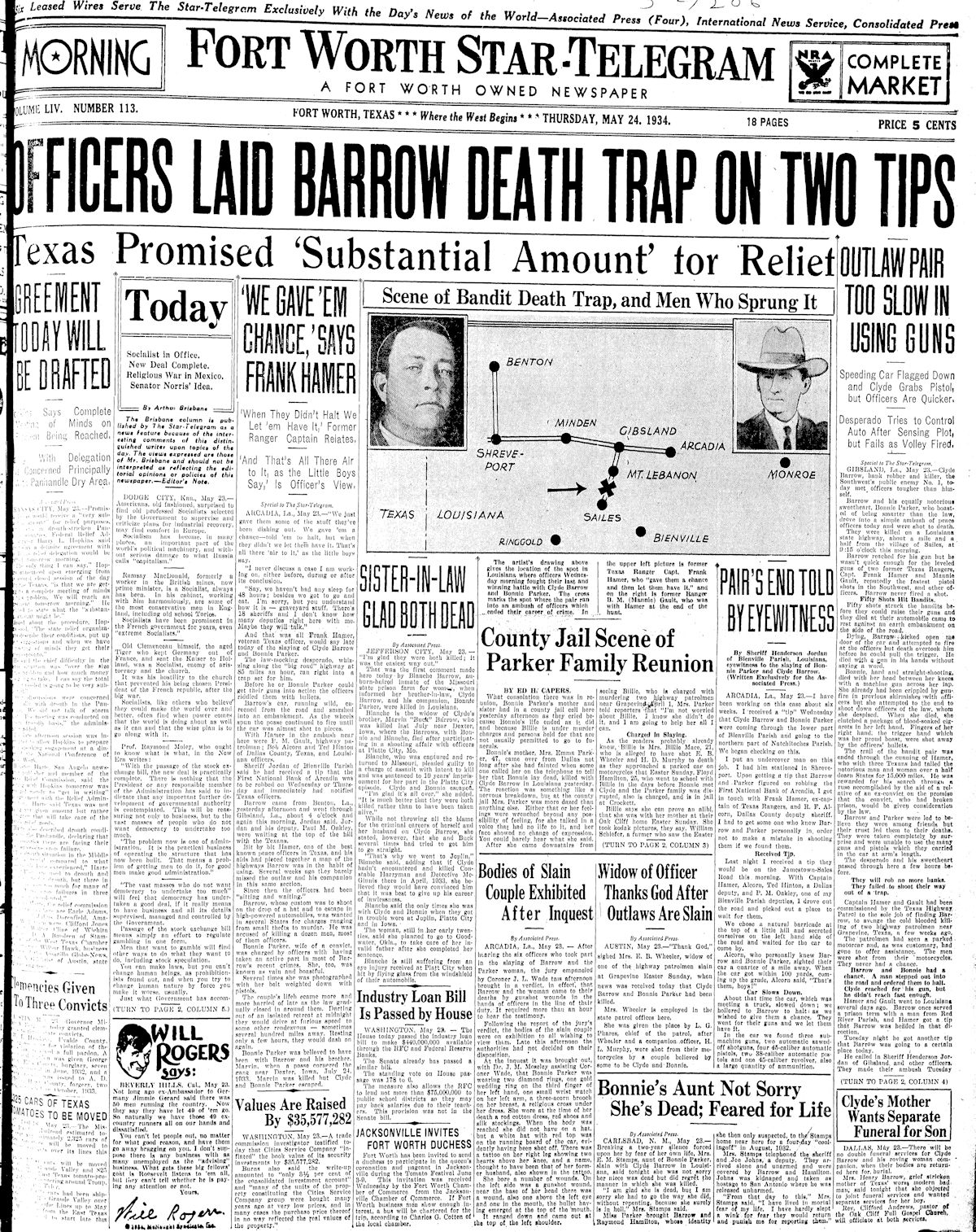

In 1967 Monroe pointed next door to the Worth Theater’s marquee, which advertised the movie Bonnie and Clyde. “Those two sold papers for me by the dozens,” he said.

In 1967 Monroe pointed next door to the Worth Theater’s marquee, which advertised the movie Bonnie and Clyde. “Those two sold papers for me by the dozens,” he said.

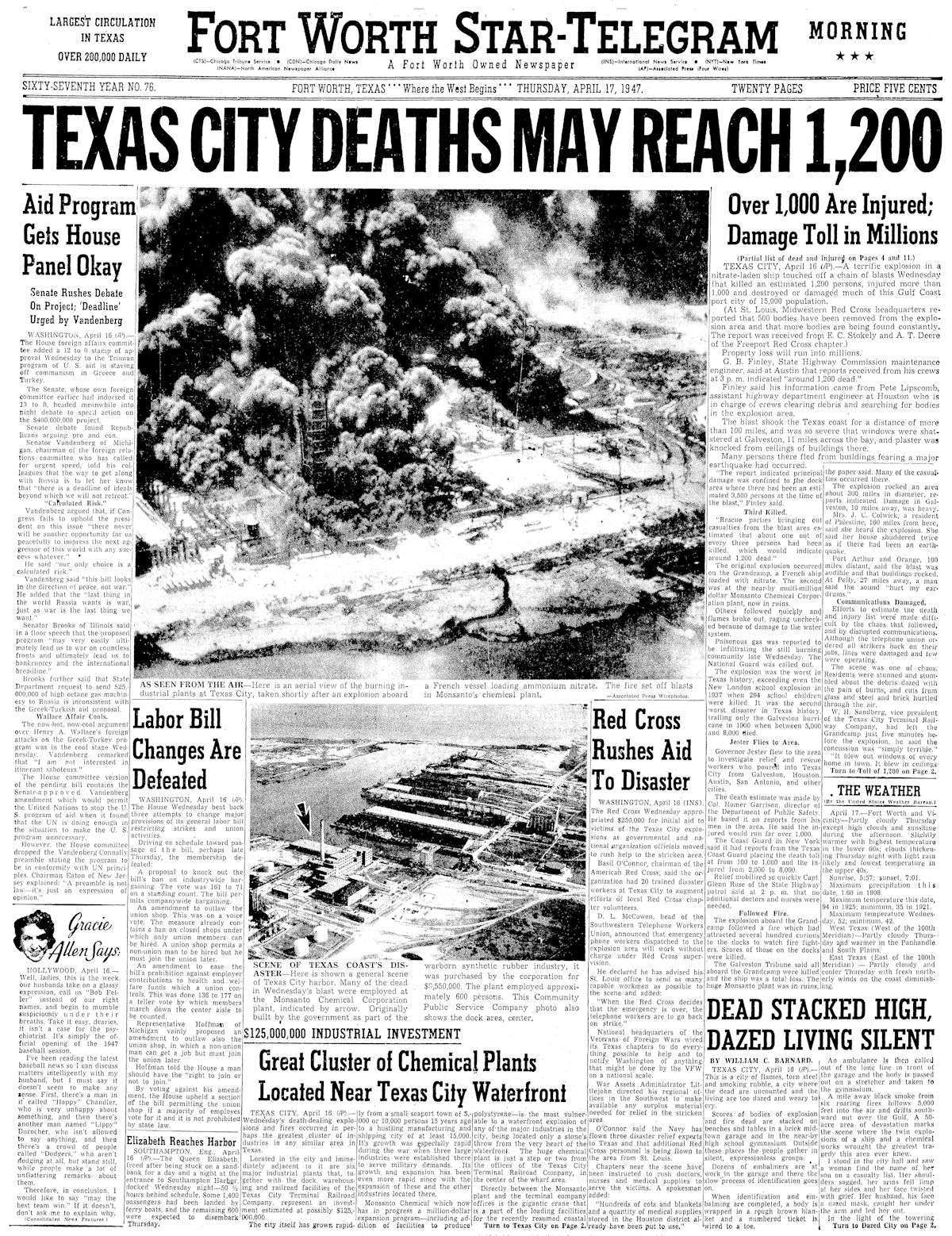

Other headlines Monroe recalled in 1967 were the New London school disaster in 1937 and the Texas City explosion in 1947.

Other headlines Monroe recalled in 1967 were the New London school disaster in 1937 and the Texas City explosion in 1947.

Monroe outlasted four managers of the Worth Hotel. One day a new manager saw Monroe and his pinewood fruit crate and his newspapers cluttering the entrance of the hotel. The manager told a desk clerk to “get rid of that old man out there.” The manager was told that he would be gone before Monroe would be.

And he was.

But by 1967 most people received their newspapers by home delivery or bought them at newsstands or vending machines. Monroe was one of the last of the newsies, a colorful anachronism.

But on he sold.

Monroe worked long hours, standing and yelling the headlines. Those hours took a toll on his twisted foot and his voice. Eventually he became hoarse, rendering his slurred speech still more difficult to comprehend. Monroe’s yell became a mumble.

In 1969 Amon Carter Jr. awarded Monroe a diamond pin in recognition of more than fifty years of service to the newspaper.

Monroe Odom would wear his pin proudly but for only two years.

Monroe Odom would wear his pin proudly but for only two years.

Of the two landmarks at the corner of West 7th and Taylor streets, Monroe Odom was the first to fall. On the night of Valentine’s Day 1971 a Star-Telegram circulation supervisor found Monroe dead beside his stack of newspapers and his pinewood podium in front of the Worth Hotel. Monroe had worked as a Star-Telegram newsie for fifty-nine years, forty-four of those years at the place where he died.

A few hours later, just a few feet away across Taylor Street, the presses printed his obituary on page 1.

His funeral was attended by people who made the news and by people who chronicled the news that he had sold most of his life: business and civic leaders, Star-Telegram writers and editors. Amon Carter Jr. anonymously paid for Monroe’s funeral. Other businessmen and customers contributed to a fund for Monroe’s widow.

During the funeral someone placed a wreath on Monroe’s pinewood fruit crate in front of the Worth Hotel. Monroe was buried wearing the diamond service pin that Amon Junior had given him.

A legend, the Star-Telegram knew, is hard to replace. The newspaper didn’t even try to replace Monroe with another newsie. It replaced man with machine, placing a newspaper vending machine on the sidewalk where for forty-four years Monroe Odom had been a landmark.

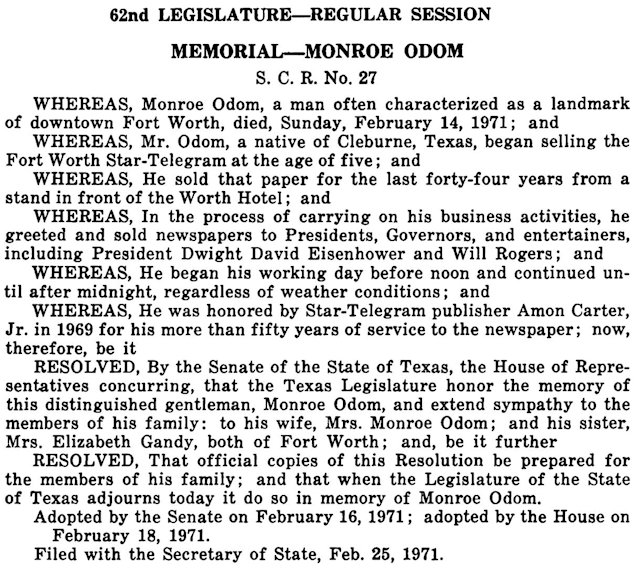

A resolution passed by the Texas legislature acknowledged Monroe as a “distinguished gentleman.”

A resolution passed by the Texas legislature acknowledged Monroe as a “distinguished gentleman.”

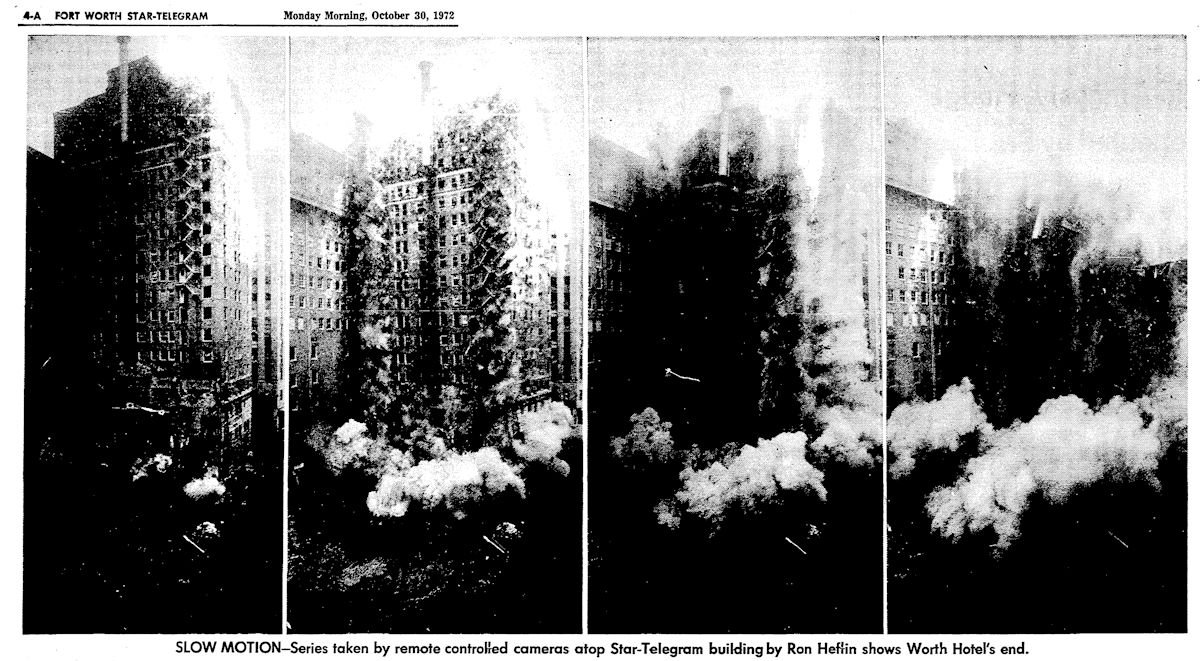

In a marriage the first spouse to die is spared having to grieve the death of the surviving spouse. And so it was in the marriage of Monroe Odom and the Worth Hotel. Twenty months after Monroe died the Worth Hotel and Theater were imploded. (Photo from Jack White Photograph Collection, University of Texas at Arlington Libraries.)

The site of the Worth Hotel and Theater is now a parking garage for the Fort Worth Club. John Monroe Odom, king of the newsies, is buried in Rose Hill Cemetery.

The site of the Worth Hotel and Theater is now a parking garage for the Fort Worth Club. John Monroe Odom, king of the newsies, is buried in Rose Hill Cemetery.

In the Key of Kay: The News Was a Nickel, But the Smile Was on the (Court)House

I loved this presentation of Fort Worth history & Mr. Odom who was really a great man & citizen.

Thank you for the presentation.

History teachers surely should know this story & share it to their students. I really doubt teachers of today will tell about all that was written-so sad to say.

Thank You

Thank you, Martha Day.

After all these decades, the Historical Marker dedication to “My Poppy, Billy Muth, 2001, drew a dedicated crowd of over 100. Tx Girls’ Choir sang,Veteran’s Memporial Dedication, Muth family members from across the US and very SPECIAL AUDIENCE MEMBERS also across TX/US paid tribute to the special “Master of the Keyboard”-Billy Muth -1902-1949. Praise God for His gift to so many theatre audiences, symphony music lovers, church attendees where his music always reached the heart of each person.