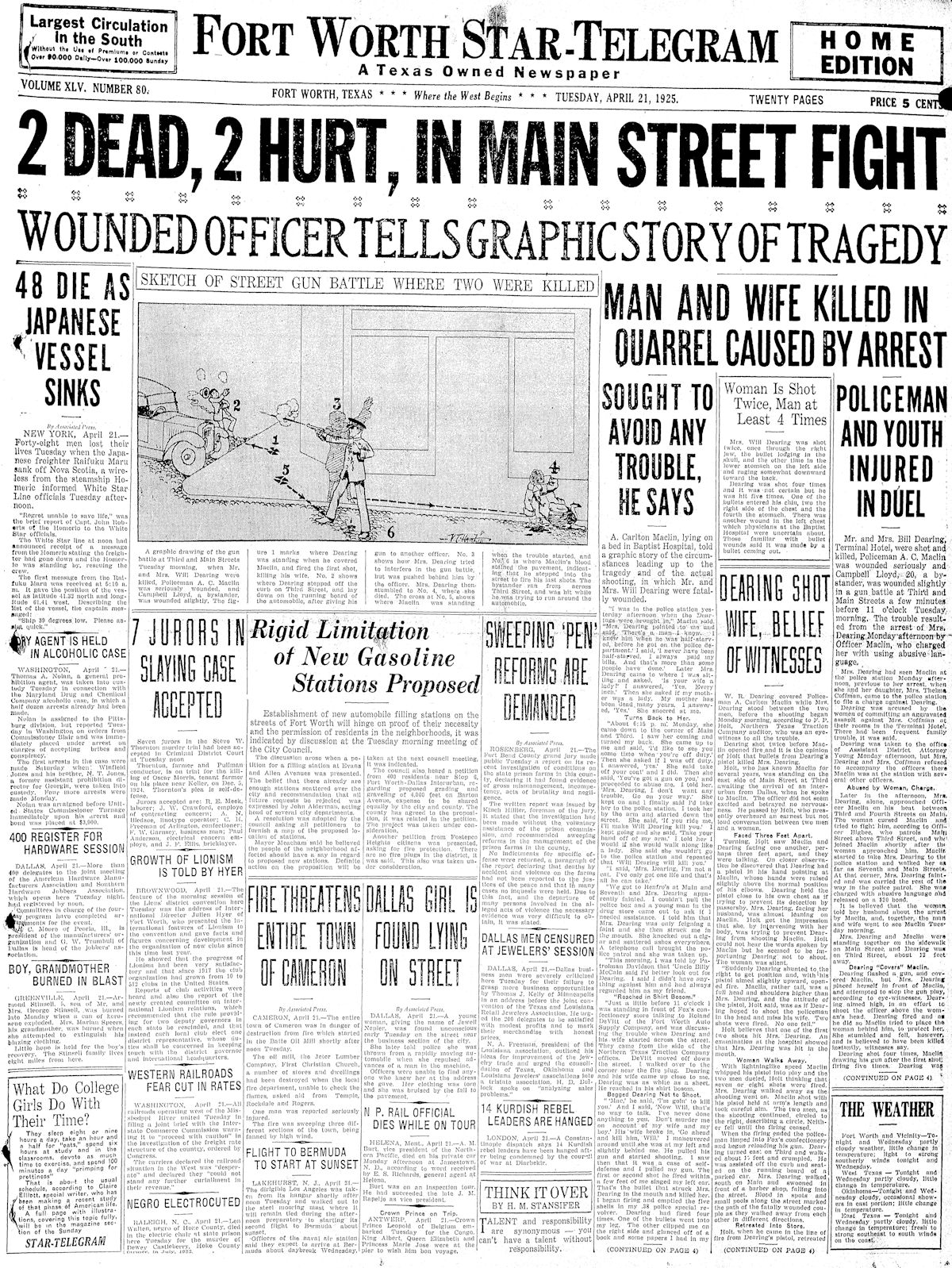

Just before 11 a.m. April 21, 1925 a husband and a wife lay dying a few feet apart near the crossroads of 3rd and Main streets downtown: Will Dearing lay on the running board of a car parked on 3rd Street just a few feet east of Main Street; Tommie Dearing lay on the pavement of Main Street just a few feet south of 3rd Street. A trail of blood drops led west from Will Dearing to the corner. A trail of blood drops led north from Tommie Dearing to the corner.

At the crossroads, in front of a confectionery shop, the two trails of blood drops converged at a pool of blood. That blood belonged not to Mr. or Mrs. Dearing but rather to police officer A. C. Maclin.

Now that we have connected the dots of those two trails of blood drops in space, let us connect the dots in time.

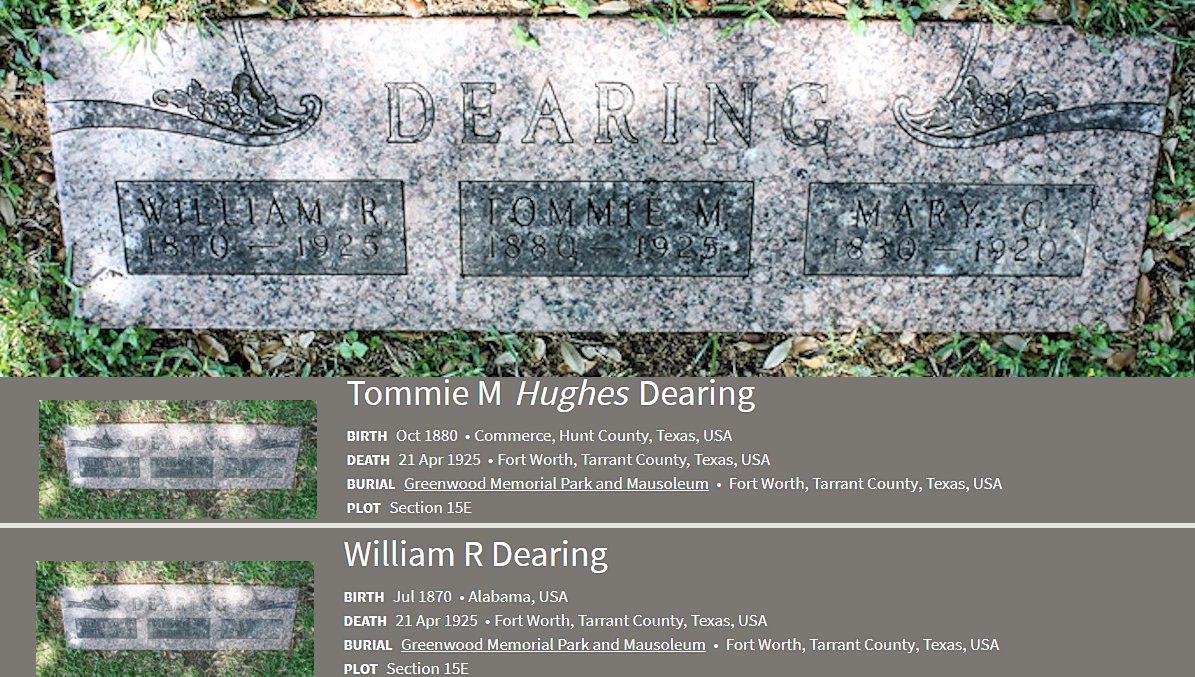

William R. Dearing was born in Alabama in 1870. Tommie Hughes was born in Commerce in 1880 and named for her father, Thomas Terrell Hughes. Will and Tommie married in 1898.

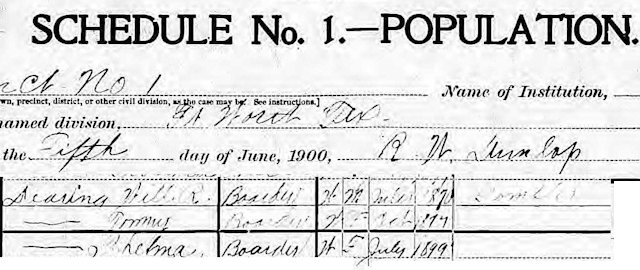

By 1900 Will and Tommie were in Fort Worth. The census listed Will as a farmer. Living with the Dearings was Tommie’s infant daughter Thelma.

By 1900 Will and Tommie were in Fort Worth. The census listed Will as a farmer. Living with the Dearings was Tommie’s infant daughter Thelma.

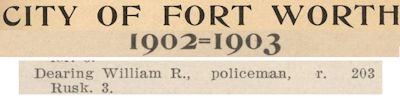

The 1902-1903 city directory listed Will as a Fort Worth police officer.

The 1902-1903 city directory listed Will as a Fort Worth police officer.

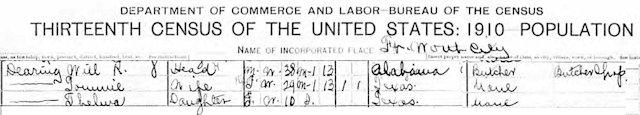

But Dearing left the force in 1907, and the 1910 census listed him as a butcher.

But Dearing left the force in 1907, and the 1910 census listed him as a butcher.

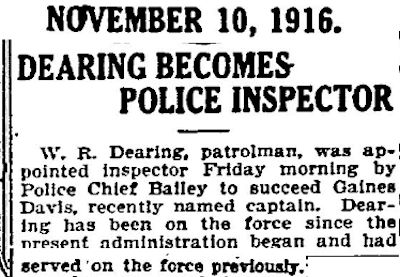

By 1911 Dearing was back on the police force and in 1916 was promoted to the rank of inspector by Chief Cullen Bailey.

By 1911 Dearing was back on the police force and in 1916 was promoted to the rank of inspector by Chief Cullen Bailey.

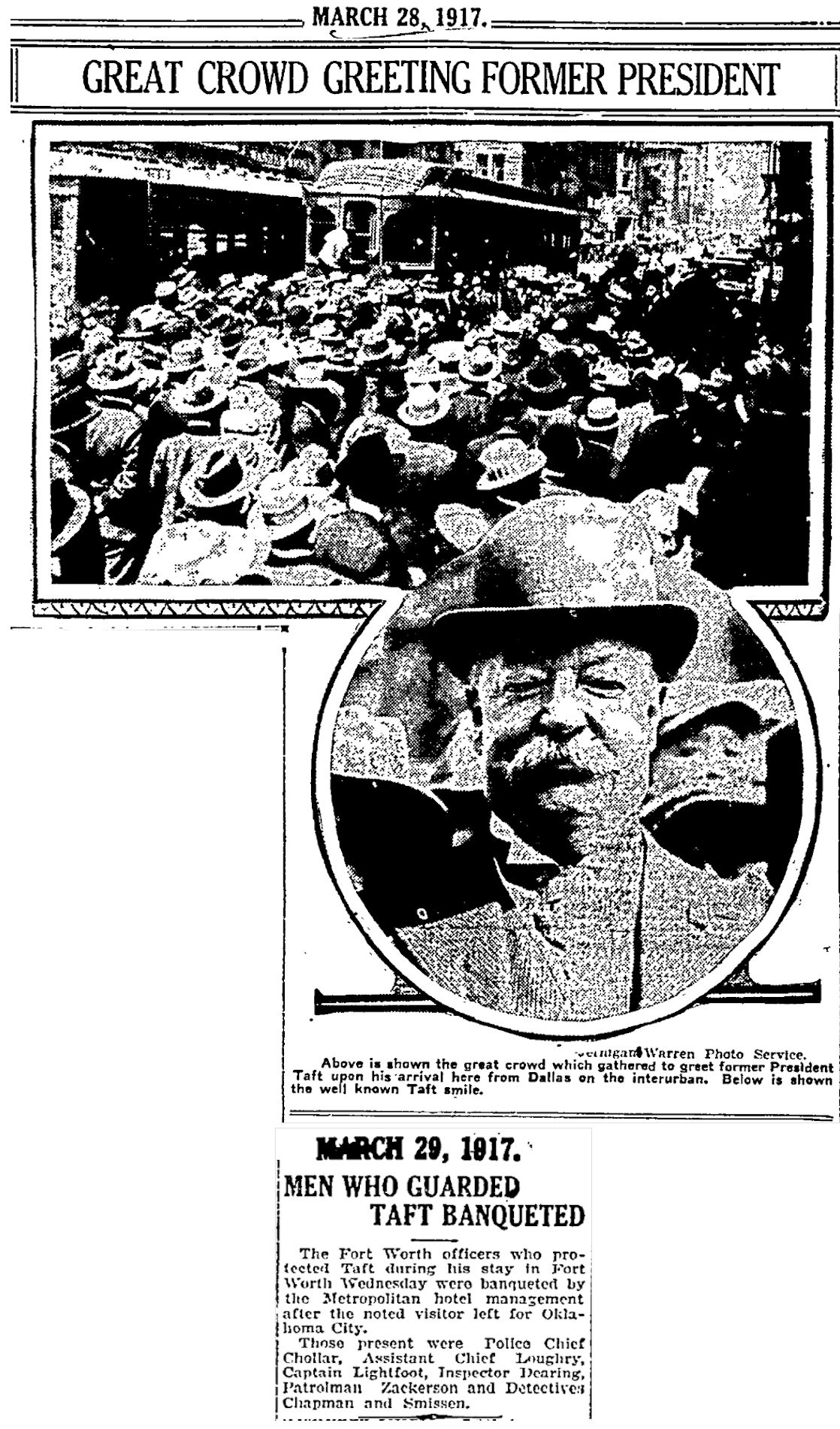

Will Dearing was one of the officers who guarded former President Taft when Taft delivered an address at the Metropolitan Hotel on March 28, 1917.

Will Dearing was one of the officers who guarded former President Taft when Taft delivered an address at the Metropolitan Hotel on March 28, 1917.

Fast-forward five months. Will Dearing was no longer a police inspector. He now worked as a special officer, keeping the peace in downtown cabarets.

Fast-forward five months. Will Dearing was no longer a police inspector. He now worked as a special officer, keeping the peace in downtown cabarets.

On the night of August 24 officer Dearing watched as Leroy Williams, a thirty-one-year-old cabaret singer, walked into a saloon at Commerce and East 4th streets.

Friends of Dearing and Williams later said bad blood had existed between the two men for years.

Dearing had arrested Williams on minor charges in the past. Dearing claimed that Williams had threatened to kill him.

The Star-Telegram later reported that earlier on August 24 Dearing and Williams “had some words” in front of a saloon on Main Street. After the two men went their separate ways Dearing stewed over the encounter.

That night Will Dearing stood at a crossroads. Two paths lay before him. How would he respond to his encounter with Leroy Williams: Get over it or get even for it?

As Dearing watched Williams walk into the saloon at Commerce and East 4th streets, Dearing was holding a twelve-gauge double-barreled shotgun loaded with buckshot. Dearing followed Williams into the saloon. Williams was standing at the bar with his back to Dearing.

“Don’t you move, you _______, I’m going to kill you,” the Star-Telegram quoted Dearing as saying.

As Williams began to turn, Dearing fired at the back of Williams’s head at close range.

As bartender W. C. Rogers watched in shock, Will Dearing turned and walked out of the saloon.

Leroy Williams was not armed when Dearing shot him. Nonetheless, Dearing, upon being arrested and charged with murder, pleaded self-defense, claiming he had felt that his life had been in danger. Will Dearing was not indicted for the shooting death of Leroy Williams.

Fast-forward to 1919. Now Will Dearing was a sheriff’s deputy—briefly. Retired Fort Worth police sergeant and historian Kevin Foster says that after Dearing left the sheriff’s department he worked at a string of jobs: bartender, cabaret bouncer. He operated a boardinghouse for a while.

Fast-forward to 1919. Now Will Dearing was a sheriff’s deputy—briefly. Retired Fort Worth police sergeant and historian Kevin Foster says that after Dearing left the sheriff’s department he worked at a string of jobs: bartender, cabaret bouncer. He operated a boardinghouse for a while.

By 1922 Dearing had changed jobs yet again. He was night watchman for an oil company.

By 1922 Dearing had changed jobs yet again. He was night watchman for an oil company.

Will Dearing’s life had begun to spiral downward. Yes, he was having trouble holding a job. But more, he and his wife, the Star-Telegram would later report, “had been rowing for several years.” And he had begun to drink heavily, Foster says. On top of that, since 1920 Dearing had faced an added challenge: At midnight on January 16, 1920 the dry wind of Prohibition had blown across the American landscape.

Will Dearing’s life had begun to spiral downward. Yes, he was having trouble holding a job. But more, he and his wife, the Star-Telegram would later report, “had been rowing for several years.” And he had begun to drink heavily, Foster says. On top of that, since 1920 Dearing had faced an added challenge: At midnight on January 16, 1920 the dry wind of Prohibition had blown across the American landscape.

To skirt Prohibition laws Will Dearing, like many Americans, resorted to concoctions that contained alcohol but remained legal: patent medicines. One such concoction was Jamaican ginger extract, a patent medicine that was 70-80 percent alcohol. The extract, known colloquially as “Jake,” had been popular even before Prohibition but became even more popular during Prohibition.

To skirt Prohibition laws Will Dearing, like many Americans, resorted to concoctions that contained alcohol but remained legal: patent medicines. One such concoction was Jamaican ginger extract, a patent medicine that was 70-80 percent alcohol. The extract, known colloquially as “Jake,” had been popular even before Prohibition but became even more popular during Prohibition.

Foster says Dearing had become addicted to Jake.

Fast-forward to 1925. After several changes of address in a few years, Will and Tommie Dearing were living in the Terminal Hotel on Lancaster Avenue at Main Street. Tommie’s daughter Thelma Coffman, now grown, lived with them. Will Dearing was now working as house detective at the Metropolitan Hotel.

In April Will Dearing’s downward spiral accelerated to the bottom during forty-eight hours of anger and ambivalence. And he took his wife down with him:

April 20

• Will Dearing’s temper had a short fuse, and that short fuse and a bottle of Jake combined to make a marital Molotov cocktail. Husband and wife argued often. Dearing became physically abusive. His wife was verbally abusive. Foster says that Dearing was “drunk on Jake” on April 20 as the Dearings and Thelma Coffman were driving downtown. Heated words were exchanged, and Dearing lost his temper. Dearing forced stepdaughter Thelma Coffman out of the moving car and into the street. Her injuries were minor, but police officer Karl Howard had witnessed the incident, stopped the car, and took the Dearings and Coffman to the police station. Will Dearing was jailed.

• At the police station Mrs. Dearing filed a charge against her husband for aggravated assault against her daughter. But inexplicably Mrs. Dearing also flew into a rage, screaming and cursing policemen present. She focused her rage on officer A. C. Maclin.

Officer Maclin later told the Star-Telegram:

“I was in the police station yesterday [April 20] afternoon when the Dearings were brought in. Mrs. Dearing pointed to me and said, ‘There is a man I know. I knew him when he was half-starved, before he got on the police department.’ I said, ‘I never have been half-starved, I always paid my bills. And that’s more than some people have done.’

“Later Mrs. Dearing came to where I was sitting and asked, ‘Is your wife a lady?’ I answered, ‘Yes, every inch.’ Then she asked if my mother was a lady. ‘My mother has been dead many years,’ I answered. ‘Yes,’ she sneered at me.”

Soon after Mrs. Dearing began abusing officer Maclin she was ejected from the station.

Officer Maclin’s sergeant told Maclin that if Mrs. Dearing returned to continue her tirade, Maclin was to arrest her.

• Mrs. Dearing went to the county Criminal Courts Building to apply for a gun permit. She told authorities there that her husband had threatened to kill her. She said that he had knocked her down with a pistol near the Majestic Theater on April 18 and that officer A. C. Maclin had refused to arrest Dearing (perhaps explaining her verbal abuse of Maclin).

After Mrs. Dearing became loud and abusive to county authorities, she was denied a gun permit and ejected from the building: her second ejection of the day.

• Later in the day she returned to the Criminal Courts Building and claimed that Will Dearing had knocked down her daughter Thelma.

But then Mrs. Dearing asked county authorities not to prosecute her husband and said she planned to leave town to avoid further trouble with him.

• Likewise, apparently Will Dearing, too, planned to leave town. And that night Dearing apparently lost or gave up his job at the Metropolitan Hotel. The Dallas Morning News later wrote: “Dearing until Monday night [April 20] was house detective at a local hotel. Dearing told several persons Monday afternoon, following the trouble between himself and his wife, that he intended to leave the city that night.”

But neither spouse left town, and their downward spiral continued.

• A few hours after Mrs. Dearing cursed officer Maclin at the police station, Maclin was on his beat downtown when Mrs. Dearing accosted him at the corner of Main and 3rd streets and renewed her tirade. Maclin told Mrs. Dearing that he was arresting her for using abusive language and disturbing the peace and tried to take her into custody. Mrs. Dearing hit Maclin in the face with her purse. Maclin responded with his billyclub.

Officer Maclin later told the Star-Telegram:

“About 6:15 p.m. Monday [April 20] she [Mrs. Dearing] came down to the corner of Main and Third. I saw her coming and turned my back. She came up to me and said, ‘I’d like to see you sometime when you’re off duty.’ Then she asked if I was off duty. I answered, ‘yes.’ She said, ‘Take off your coat’ and I did. Then she said, ‘You’ve got a gun on you’ and proceeded to abuse me. I told her, ‘Mrs. Dearing, I don’t want any trouble. Go on your way.’ She kept on and I finally said I’d take her to the police station. I took her by the arm and started down the street. She said, ‘If you ride me, I’ll make Will Dearing kill you.’ I kept going and she said, ‘Take your hand off of my arm.’ I told her I would if she would walk along like a lady. She said she wouldn’t go to the police station and repeated that ‘Will Dearing will kill you.’

“We got to Renfro’s [drugstore] at Main and Seventh and Mrs. Dearing . . . struck me in the mouth. She knocked out a cigar and scattered ashes everywhere. A telephone call brought the police patrol and she was taken up.”

• Mrs. Dearing joined her husband in the city jail.

• The couple was released from jail on bond that night.

The Dearings did not seem to hold a grudge against officer Howard for his arrest of Dearing. But officer Maclin’s arrest of Tommie stuck in the Dearings’ craw. That night Will Dearing again stood at a crossroads. And his wife stood with him. Two paths lay before them. How would the Dearings respond to officer Maclin’s treatment of Tommie: Get over it or get even for it?

Will and Tommie Dearing chose the path that would lead them to the corner of Main and 3rd the next day.

April 21

• Foster says Will Dearing telephoned the police station three times in the morning to ask which beat officer Maclin was working.

• An officer was dispatched to warn Maclin about Will Dearing.

Officer Maclin later told the Star-Telegram:

“This morning [April 21] I was told . . . better look out for Dearing. I said I didn’t have anything against him and had always regarded him as my friend.”

• About 10:30 a.m. the Dearings met downtown with a lawyer about the charges facing Mrs. Dearing. The Star-Telegram later reported that the Dearings said they “had it in for Maclin and were going to get him.”

• Just before 11 a.m. the Dearings were walking downtown. When they reached the southwest corner of 3rd Street at Main they saw officer Maclin standing on the southeast corner across Main Street. (These corners today are on the northern edge of Sundance Square Plaza.)

Will and Tommie Dearing stood at 3rd and Main streets looking at officer Maclin.

The Dearings had reached their crossroads.

They crossed it.

Officer Maclin later told the Star-Telegram:

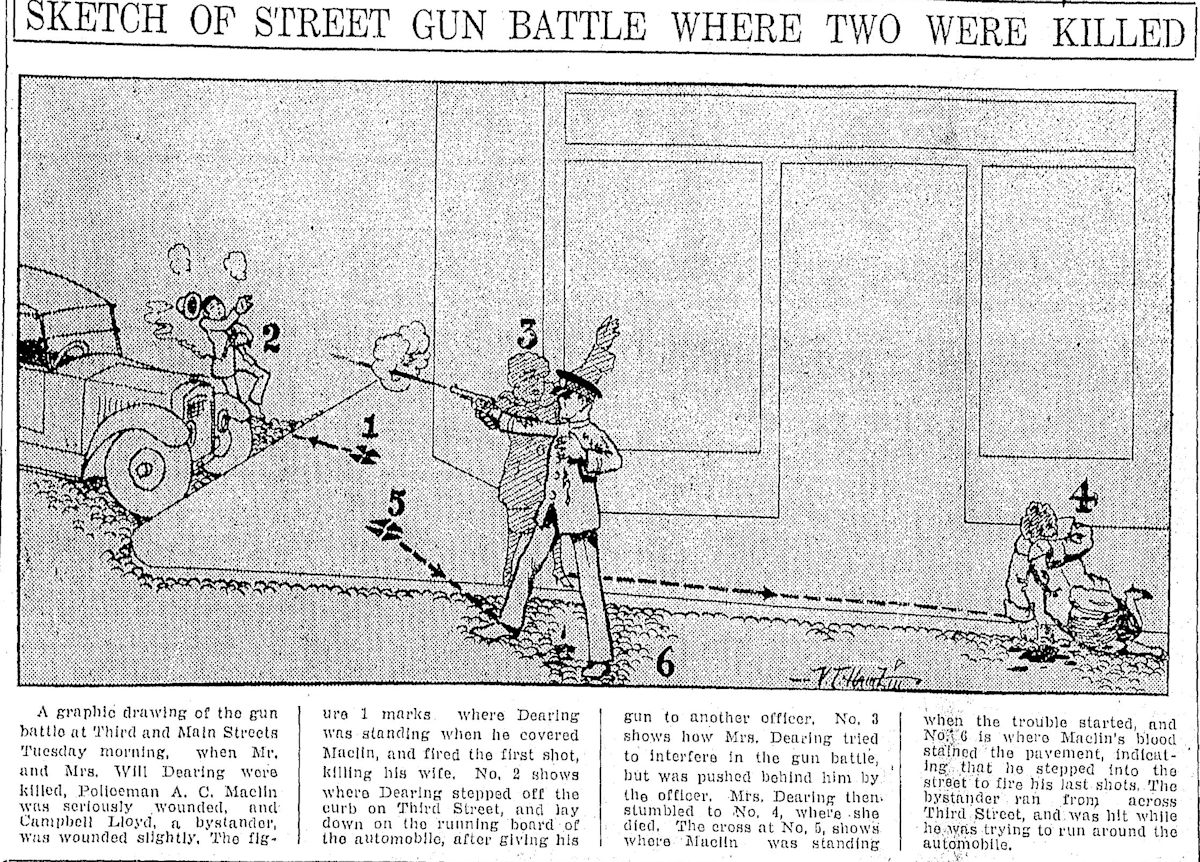

• “Just a little before 11 o’clock I was standing in front of Fox’s confectionery store . . . when Dearing and his wife started across the street. They came from the side of the Northern Texas Traction Company offices. . . . I walked over to the corner near the fire plug. Dearing and his wife came up close to me. Dearing was as white as a sheet. He reached in his shirt bosom.

“‘Mac,’ he said, ‘I’m going to kill you.’ And I said, ‘Now Will, that’s no way to talk. I’ve never done anything to you. Don’t murder me on account of my wife and my boy.’”

Officer Maclin later told the Dallas Morning News:

“When I saw Dearing and his wife coming, I knew what they were coming for. Dearing unbuttoned his coat as he crossed the street, and as he stepped up on the curb he pulled his gun. But still I made no motion to get my gun. I hoped I could talk him out of it. He cursed me and declared he was going to kill me, and I begged him not to murder me, for the sake of my wife and kid.”

At this point, according to Maclin, Mrs. Dearing grabbed Maclin by the left arm and broke in: “Go ahead and kill him, Will.”

Maclin told the Star-Telegram how he tried to shield Mrs. Dearing and innocent bystanders from gunfire:

“I maneuvered around until she was at my left and slightly behind me. He pulled his gun and started shooting. When I saw it was going to be a case of me shooting in self-defense, I maneuvered so that if I missed, my bullets would hit against the brick wall of Renfro’s drug store. I purposely picked an angle in a northeasterly direction so that no innocent bystanders would be hit by any of my bullets. Dearing was firing straight at me and down the street.”

The Star-Telegram reported: “Maclin shot with his pistol at arm’s length and took careful aim. The two men, as the shooting continued, circled to the right, describing a circle. Neither fell until the firing ceased.”

April 21 was a Tuesday. At 10:50 a.m. downtown was crowded.

Maclin recalled: “How in the name of God I wasn’t killed or someone else walking the streets wasn’t killed, I don’t understand. . . . I pulled my gun. The first or second shot he [Dearing] fired within a few feet of me singed my left ear. That’s the bullet that struck Mrs. Dearing in the mouth and killed her.”

The Dallas Morning News wrote: “Maclin maintains, and witnesses express [the] same belief, that Dearing shot his wife in firing at the officer.”

Maclin told the Star-Telegram: “I began firing and emptied the five shells in my .38 police special revolver. Dearing had fired four times. One of the bullets went into my leg.”

At this point in the shootout officer Maclin’s life possibly was saved by circumstance: (1) He was carrying a book in his shirt pocket and (2) Dearing’s pistol misfired:

“The other [bullet fired by Dearing] clipped me on the right side and glanced off of a book and some papers I had in my blouse. Dearing still had one shot to fire. I was looking him straight [in] the eye when he pulled the trigger the fifth time. The pistol snapped and I hobbled into the confectionery store. I pulled out three cartridges and stuffed them in my pistol. Someone helped me stand up and I went out again. I didn’t think Dearing had been badly hurt until I saw him lying on the fender of an automobile.”

After Tommie Dearing was shot she staggered south a few feet on Main Street and collapsed on the pavement in front of Swain’s Barber Shop. Will Dearing staggered east along 3rd Street a few feet and collapsed on the running board of a parked car.

Another policeman, upon hearing gunshots, had rushed to the scene and taken custody of Will Dearing on the running board.

Dearing looked at the officer, surrendered his pistol, and said, “I’m killed.”

In a matter of seconds nine shots had been fired: five by officer Maclin, four by Will Dearing. Will Dearing was hit four times, his wife two times, Maclin two times, and bystander Campbell Lloyd one time. Lloyd had been standing on the corner across 3rd Street (at the Knights of Pythias building) when he was struck in the leg by a stray shot fired by Maclin. (1925 photo from University of Texas at Arlington Libraries.)

After the shooting stopped, the Star-Telegram wrote, one thousand people gathered at the crime scene. A detail of police officers was dispatched to keep traffic moving.

After the shooting stopped, the Star-Telegram wrote, one thousand people gathered at the crime scene. A detail of police officers was dispatched to keep traffic moving.

Will and Tommie Dearing were dead on arrival at local hospitals.

The Dearings were buried on April 22.

The Dearings were buried on April 22.

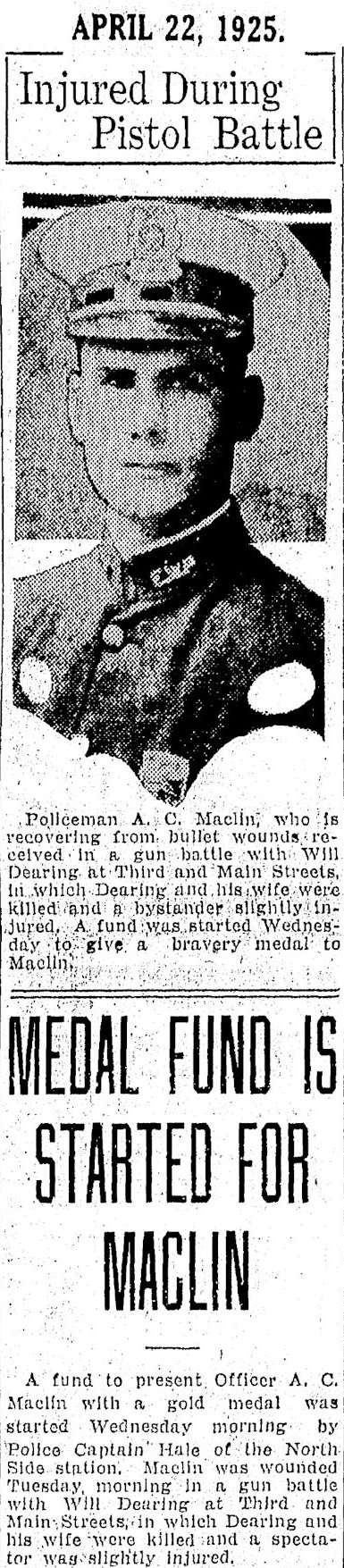

On the day the Dearings were buried, a fund was started for a medal to honor Maclin for his bravery.

On the day the Dearings were buried, a fund was started for a medal to honor Maclin for his bravery.

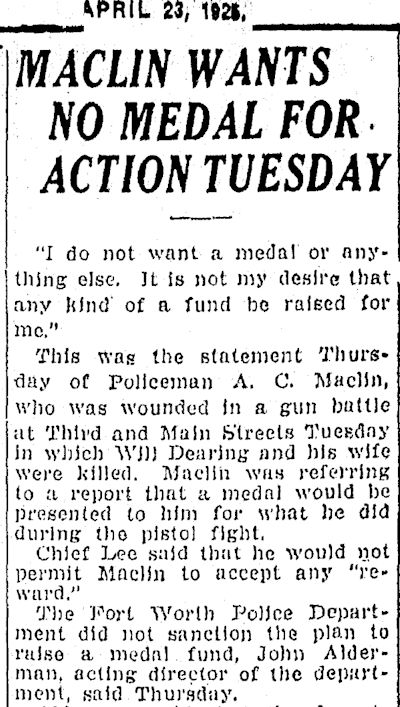

But Maclin said he did not want a medal. He recovered from his wound and resumed his career on the police force. Bystander Campbell Lloyd also recovered from his wound.

But Maclin said he did not want a medal. He recovered from his wound and resumed his career on the police force. Bystander Campbell Lloyd also recovered from his wound.

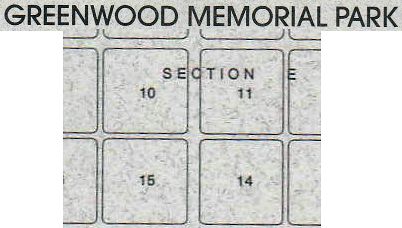

The Dearings are buried in Greenwood Cemetery’s section E, block 11. (Mary C. was Will’s mother.)

The Dearings are buried in Greenwood Cemetery’s section E, block 11. (Mary C. was Will’s mother.)

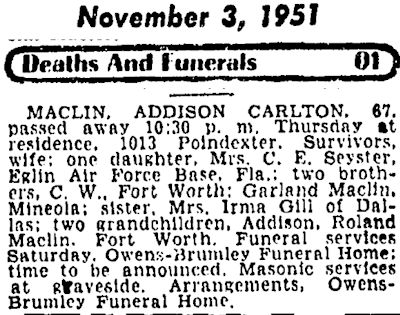

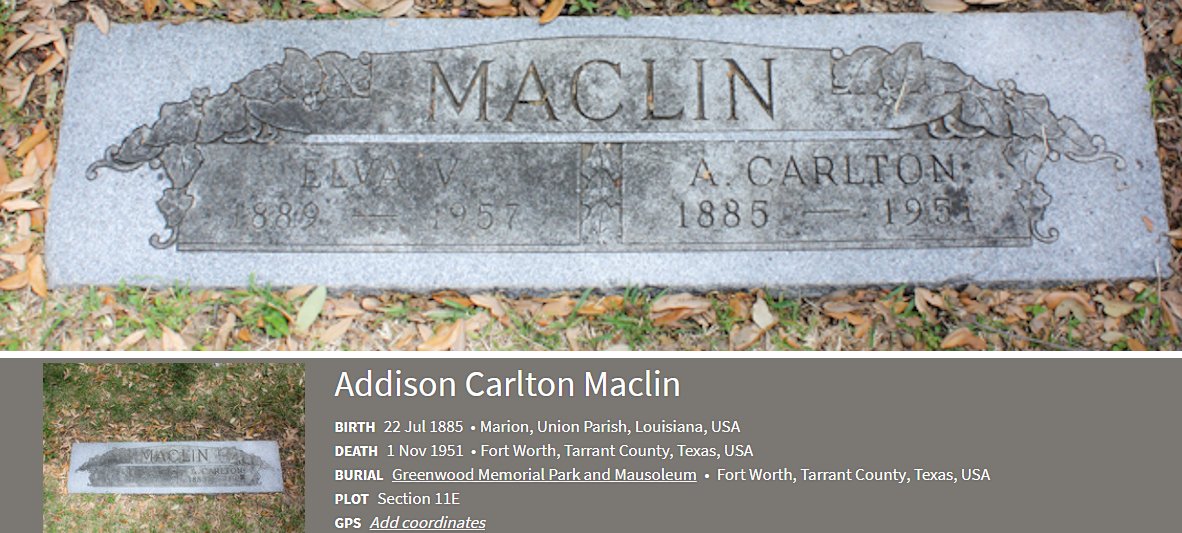

Police officer Addison Carlton Maclin died in 1951.

Police officer Addison Carlton Maclin died in 1951.

Maclin also is buried in Greenwood Cemetery’s section E, block 15, about four hundred feet from the Dearings.

Maclin also is buried in Greenwood Cemetery’s section E, block 15, about four hundred feet from the Dearings.

As you can see, between the Dearings in block 11 and Maclin in block 15 lies a crossroads.

As you can see, between the Dearings in block 11 and Maclin in block 15 lies a crossroads.

(Thanks to retired Fort Worth police sergeant and historian Kevin Foster for the tip and the help.)

Fantastic story! I loved the way you told it too!

Thanks, Kevin. Another wild episode in Cowtown. Could not have told the tale without you.