In May 1893 R. D. Hunter received this message in the mail:

Who were R. D. Hunter, W. K. Gordon, and the other men named, who were the “avengers,” where was “the road to Jimmy’s,” and why had the closing of said road motivated said “avengers” to send Hunter et al. such a valentine?

To answer these questions, let us step back in time and in space: in time to 1880 and in space seventy miles west of Fort Worth to what one early chronicler called, rather grandly, “the Erath Mountains”: “There is nothing in the Erath Mountains to invite human activities. The winding, barren hills have stood for centuries as frowning sentinels over waste plains where the wolf and cougar could scarce make shift [contrive] for a living.”

Ah, but then into those winding, barren hills came William Whipple Johnson of Strawn in southern Palo Pinto County. In 1880 Johnson was having difficulty finding timber to fulfill his contract to provide lumber for fence posts and railroad ties to the Texas & Pacific railroad, which was laying track westward toward Sierra Blanca. He needed more timbered land. In his search Johnson met a farmer in northern Erath County. The farmer told Johnson that, alas, he, too, was having difficulty: He was having difficulty digging a water well on his land because he had struck a dadgummed layer of black rock.

“Black rock, you say? Dadgum,” no doubt said the savvy Johnson to himself.

But not until 1886 would Johnson have enough money to buy the tract of land that he judged to be most suitable for extracting that black rock—the Pedro Herrera survey in those winding, barren hills of the Erath Mountains. In October Johnson sank a shaft sixty-five feet deep. Sure enough: He hit a vein of coal twenty-six inches thick.

Paydirt!

The Johnson Mines were soon in production, manned by miners who were members of the Knights of Labor union. Around the mines formed a settlement known as “Johnsonville.” Johnson built a general store for the miners, who lived in tents and shacks. The miners had a Knights of Labor meeting hall.

In 1887 the T&P railroad laid a spur from its track three miles south to the mines to haul out Johnsonville coal for its steam locomotives. In the beginning the T&P was Johnsonville’s only customer, but eventually a dozen other railroads would buy coal from the mines.

William Johnson paid decent wages ($1.75-$1.95 a ton—about $50 today). Perhaps too decent: In September 1888 he failed to make his payroll for August.

His miners went on strike.

Enter Colonel Robert Dickie Hunter (photo from Ancestry.com). Hunter, born in Scotland in 1833, had come to America with his parents at age nine. He had lived in Colorado and then St. Louis and developed interests in first cattle and then mining.

Soon after William Johnson had opened his mine in Erath County, he had encountered financial difficulty. Johnson through his attorney had received a loan from Hunter, putting up Johnsonville as collateral. About that time Hunter moved to Texas from St. Louis and visited the Johnson mines. He was impressed. On the day the Johnsonville miners struck in September 1888, R. D. Hunter, along with Horace Kingley Thurber of New York and M. B. Loyd, S. P. Greene, and J. Y. Hogsett of Fort Worth, met at the Mansion Hotel in Fort Worth to organize the Texas & Pacific Coal Company (no relation to the railroad company).

In October 1888, one month after William Johnson’s union miners went on strike, Hunter and his new company bought the Johnson mines.

Colonel Hunter immediately made some changes.

Hunter paid lower wages ($1.15-$1.40 a ton) than Johnson had paid.

Hunter paid miners only for large, not small, chunks of coal dug from the mines.

Hunter allowed no unions.

Hunter had the mining settlement enclosed by a six-foot-tall, four-strand, barbed-wire fence. The fence was patrolled by armed guards on horseback. The fence kept union organizers out. The guards kept the peace among Johnsonville residents—and ejected union organizers who managed to infiltrate. The miners referred to the fence as “the wire.” It came to symbolize the company’s control over them.

Hunter soon realized that he had bought a headache: The union miners of Johnsonville considered themselves to be still on strike, but Hunter did not consider them to be his employees. In his view he had bought the mines, not the miners. Hence, he needed to hire 700-1,000 new—and nonunion—miners.

According to Don Woodard in Black Diamonds! Black Gold!: The Saga of Texas Pacific Coal and Oil Company, Hunter told the striking miners: “I will run my business or run it to hell.”

On December 17 the Dallas Morning News reported that “riotous miners” had “inaugurated a reign of terror” and had vowed that “no new employes shall work at the Johnson coal mines.” Colonel Hunter reported that “rowdies” had been firing pistols and throwing rocks in Johnsonville. He asked the governor to dispatch state troops.

The striking miners considered any new miners who went to work for Hunter to be scabs and intimidated prospective miners as they arrived. Accordingly, many miners who arrived from the East to work at Johnsonville found the situation to be dangerous and returned to the East.

On December 22 the sheriff of Erath County also asked the governor to send troops because although the sheriff could keep the peace at the mines while he was there, as soon as he left, the “desperadoes” “intimidate the guards and employes by threats and violence.”

One night in December, the Fort Worth Gazette reported, “a large squad of men” surrounded the offices of the mine management and riddled the building with “several hundred shots.”

So, on December 22 Texas Adjutant General W. H. King dispatched ten Texas Rangers under Captain Sam McMurry to Johnsonville to keep the peace, “and with their presence rioting ceased,” the Gazette reported. But striking miners continued to intimidate prospective new miners. So, in early 1899 the Rangers began escorting new miners, many of them arriving by train from Pennsylvania, from Fort Worth to Johnsonville, and eventually the mine resumed operation with its new employers and its new employees.

With relative labor peace established, in January 1889 Colonel Hunter made another change: He renamed the mining settlement “Thurber” in honor of his friend and partner.

Also in 1889 Hunter became one of the early residents of Fort Worth’s Quality Hill, renting a house at the corner of West Daggett and Summit streets.

With his new mine with its new employees and new name in operation, R. D. Hunter in 1889 made a management decision that would affect Thurber and Texas and, indeed, America for the next thirty years: He hired twenty-seven-year-old William Knox Gordon. Gordon had been born in Spotsylvania, Virginia in 1862. Trained as a civil engineer, he had worked for railroads in Virginia, North Carolina, and Georgia before moving to Texas in 1889 to survey a route for Hunter’s proposed railroad between Thurber and Dublin. That’s when Gordon came to the attention of Hunter, who hired him as a mining engineer but soon gave him management responsibilities. By 1892 Gordon would be superintendent of Thurber.

Colonel Robert Dickie Hunter, with important contributions by William Knox Gordon, would make Thurber one of the largest producers of bituminous coal in Texas, producing three thousand tons of coal a day. By 1913 Thurber would be, according to Black Diamonds! Black Gold!, the largest city on the T&P railroad line between Fort Worth and El Paso. At its peak Thurber would have a population of about eight thousand, one-quarter of whom worked in the mines. By 1913 Thurber would produce 700,000 tons of coal a year.

The company would eventually take coal from fifteen mine shafts and control seventy thousand acres in Erath and Palo Pinto counties.

But in 1890, after only a few months of peace at Thurber, on July 5 Colonel Hunter again asked Texas Adjutant General W. H. King to send Captain McMurry and a few Rangers to Thurber because Hunter feared more labor violence instigated by “a lot of bad men” “loitering” in the area, among whom, he claimed, were Knights of Labor union members and “well-known horse thieves and ex-convicts.”

After arriving in Thurber McMurry reported finding “considerable disorder,” but he and his men kept the peace and departed after less than a month.

Fast-forward through four years of relative labor peace to 1894.

Texas & Pacific Coal Company had been born in Fort Worth in 1888, and although the coal was mined in Thurber, the company’s headquarters remained in Fort Worth in the Hurley Building.

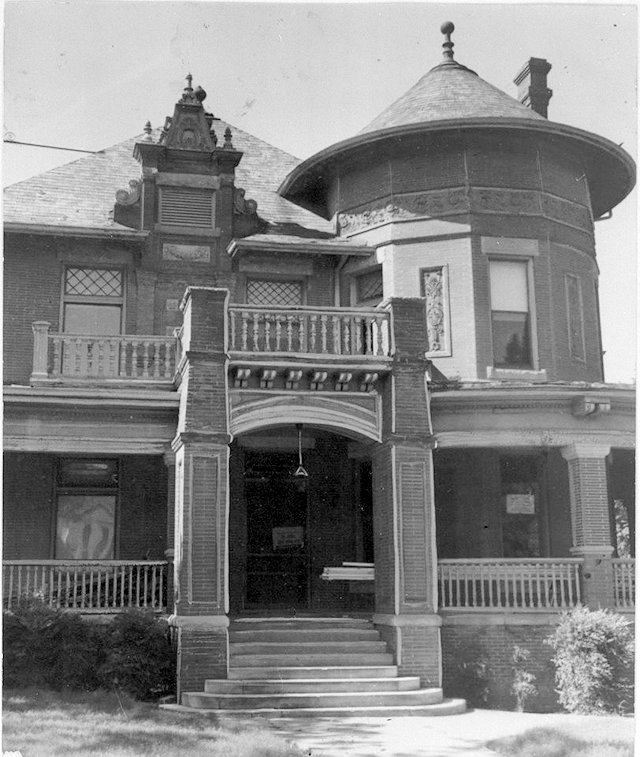

And R. D. Hunter was still on Quality Hill, living at 1418 El Paso Street. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library Special Collections.)

And R. D. Hunter was still on Quality Hill, living at 1418 El Paso Street. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library Special Collections.)

By 1894 two facts defined Thurber:

1. The once-modest mining settlement of Thurber had grown into a town—a company town. In fact, Thurber was the largest company town in the state. Texas & Pacific Coal Company owned everything in town from the bottom of the mine shafts to the top of the smokestacks. All the buildings, all the infrastructure, all the mules, all the machinery. Everything but the people.

(One miner said Colonel Hunter was “a feudalist of old who dreamed of a strictly monopolistic empire.”)

2. Thurber was a nonunion workplace.

And in 1894 two events related to those two key facts would define the year for Thurber.

First, Texas & Pacific Coal Company created a subsidiary: Texas & Pacific Mercantile and Manufacturing Company. This company would operate all mercantile establishments in Thurber: the grocery, dry goods, hardware, and drug stores.

One of Thurber’s company stores. (Photo from Texas Historical Commission.)

The company drugstore. (Photo from Texas Historical Commission.)

Thurber also had a barber shop, photo studio, a stockade, fire department, job printing plant, ice plant, electric plant, waterworks, cotton gin, and two hotels, one of which, the Knox Hotel, was touted as “the best hotel west of Fort Worth.”

There were two lakes, the larger of which (155 acres) was stocked with fish and supplied Thurber with water. Before the waterworks was built, water from the lake was hauled to residents’ houses by tank wagon (W. K. Gordon designed the larger lake and supervised its construction).

The company also built housing—mostly board-and-batten shotgun houses—to rent to its residents. Each house had a stove (coal-burning, of course) inside and a privy outside. Women sometimes papered the bare pine walls with sheets of newspaper. For single miners there were boardinghouses where five or six miners shared a room. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

The town had a library (the county’s first), its own cattle ranch, its own dairy, its own brick plant (see Part 2), fraternal lodge halls, a public school, a parochial school, and a school for African Americans, a cemetery (with separate entrances for Catholics, Protestants, and African Americans).

Thurber had churches for Methodists, Baptists, Catholics, and African Americans. Photo shows St. Barbara’s Catholic Church. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

In 1894 Thurber’s weekly newspaper, Texas Miner, began publication.

Eventually Thurber had an amateur baseball team, two bands, one bandstand, a golf course, tennis courts, and a six hundred-seat opera house (New York’s Metropolitan Opera company performed there).

Oh, and the men of Thurber enjoyed badger fights.

Lastly, there were two saloons (the Snake and the Lizard). The Snake and the Lizard received beer in refrigerated boxcars from Texas Brewing Company.

Aside from the beer, by early in the twentieth century Thurber would be largely self-sufficient.

And Thurber in most respects appeared to be a conventional town, but it was a town without municipal government and city taxes. The company was the government. Because Thurber had no unions and no elected city officials, workers had little say in town affairs.

A company town could be described positively as parental and negatively as authoritarian. E. G. Senter of Texas Farm & Ranch magazine wrote of Thurber in 1898: “The town has its own code, which is more rigorous than the statutes, and when that is violated a writ of ouster is served and rigidly enforced.”

No gambling, no prostitution. And no drunkenness. Mining was dangerous enough when the miners were sober. By order of Colonel Hunter via W. K. Gordon, Thurber bartenders did not overserve patrons. A worker could be discharged for drunkenness.

And in lieu of taxes the company collected payment from the miners for the goods and services it provided them. So, the company paid wages to its workers and provided goods and services to them, but the company got back some of those wages. (Think Tennessee Ernie Ford’s “Sixteen Tons.”)

Thurber employees were paid in scrip, which was legal tender only in Thurber. When employees spent their wages—at the company stores, at the saloons, at the opera house—when they paid their rent (a three-room house rented for $6 a month, fifty cents extra for a porch), when they bought their water from the Thurber lake (ten to twenty-five cents a barrel), paid their electric bill (twenty-five cents per outlet a month), and paid for their health care (fifty cents a month), their wages were returning to the company.

Those employees made Thurber a sooty, simmering pot of goulash: native-born Americans worked alongside immigrants from eighteen countries, including Italy, Poland, Britain, and Ireland and smaller numbers from Mexico, Germany, Belgium, France, Sweden, Austria, and Russia. (According to Thurber historian Leo Bielinski, Thurber’s priest heard confessions in six languages.)

The newspaper was printed in English and Italian.

But miners didn’t have much time to read their newspaper. They went to work at 6 a.m. Thurber was a sprawling compound. If a miner’s assigned mine was close to his shotgun house or boardinghouse, he walked to “the office.” If his mine was distant, he rode the Black Diamond, a shuttle train (for which he paid a fare to the company). At noon he traded a pick for a pail and ate his lunch (bought from the company store) in the mine. He did not tarry over his lunch. Because he was paid by the ton, a quick lunch meant a bigger check. After lunch he picked up his pick and swung it until 5:30.

Thurber’s mine shafts were from 52 to 327 feet underground. Men dug the coal, and mules hauled it out of the mines. The ceilings of the mines were not high enough for men to stand upright—in some mines only twenty-six inches high. Miners crawled on hands and knees, lay on their side, or sat cross-legged to swing a pick at the coal face.

Mining engineer W. K. Gordon helped to make mining safer at Thurber, but mining remained a dangerous occupation. Miners were killed or maimed in cave-ins, explosions, and machinery accidents, by poisonous gas and flooding. Miners died of black lung (pneumoconiosis). Mining at that time also was very physical—more picks and shovels than dynamite.

The second event of 1894 that would define the year for Thurber was another labor-management conflict. Only this time the conflict had a head on it: labor-management-beer.

The brewhaha actually dated back to 1888 when Jimmy Grant had opened a saloon just outside the mining settlement. After Colonel Hunter took over the settlement, he began a crusade against Grant’s saloon for three reasons: (1) Jimmy Grant’s saloon competed with the Thurber saloons for the miners’ business, (2) Jimmy Grant, unlike Thurber bartenders, had no incentive to limit how much patrons drank, but more important, (3) whereas Thurber’s saloons were monitored by Hunter’s security guards, Grant’s saloon offered miners a sanctuary where they could safely vent about wages, work conditions, and such and—even more alarming to Colonel Hunter—fall prey to the seduction of union organizers.

At Hunter’s behest, the Erath County sheriff began conducting raids on Grant’s saloon, arresting patrons for gambling, being drunk and disorderly, discharging firearms.

Jimmy Grant took the hint: In early 1893 he moved his saloon north into Palo Pinto County. But the saloon’s new location was near a wagon road that led from the T&P main track south to Thurber, thus the men of Thurber could continue to find sanctuary, solace, and suds at Jimmy Grant’s.

Soon after relocating, Grant sold controlling interest of his saloon to Maynadier T. Bruce and D. W. Stewart. (Photo of Bruce is from John O. Casler’s Civil War memoir Four Years in the Stonewall Brigade.)

But Colonel Hunter was not done with the rival saloon.

To prevent his men from frequenting Bruce and Stewart’s saloon, Hunter (1) declared it off-limits and (2) closed the wagon road leading to the saloon from Thurber. (Grant’s relocated saloon would be the seed of a settlement of its own—Granttown—where today stands the town of Mingus.)

Soon after, in May 1893, Hunter received the threat from the “avengers”: If he did not reopen “the road to Jimmy Grant’s saloon” and fire W. K. Gordon and four other Thurber officers, he would be killed. Hunter countered by offering a $200 reward for the arrest and conviction of the “avengers.”

Well, it was pretty obvious who would have such a grudge against Hunter, Gordon et al. In autumn of 1893 Grant, Bruce, and a third man were indicted, and in December they were arrested and charged with sending the threatening letter.

Now it was Bruce’s move. While he was awaiting trial, he and D. W. Stewart filed a lawsuit against Hunter and Texas & Pacific Coal Company, accusing them of using “threats, tyranny and coercion over the servants and employes” of Thurber to drive away “nearly all of plaintiffs’ customers.” Bruce and Stewart asked for $10,000 ($290,000 today) in exemplary damages.

In April 1894 the Fort Worth Gazette reported on the status of the case against Bruce and colleagues and reprinted the threatening letter (with the canine genealogy redacted).

Meanwhile, the personal feud of Hunter versus Bruce and Stewart was playing out against a larger feud. In March 1894 Colonel Hunter had reduced wages. Discontent spread among the miners.

And in April the United Mine Workers union had called a general strike. More than 200,000 men nationwide went on strike demanding that wages be raised to their level before the economic panic of 1893.

During the nationwide union strike, labor organizers came to Thurber to urge the miners to strike. Such “agitators” were not welcomed by the company. Nosiree. Not by a long shot. Two newspaper clips show opposing views of the same incident by labor and management. A miner told the Fort Worth Gazette that he had been arrested as an agitator, escorted out of town, threatened with hanging, and shot at as he fled his escorts. But Thurber’s Texas Miner insisted that “No violence was attempted or threatened” despite the fact that the agitator “had the Italians, Poles and French organized, and only needed the negroes now to join ’em for a strike.”

June 1894 was a confrontational month at Thurber.

First Bruce and Stewart fought back against Colonel Hunter: Stewart infiltrated Thurber and posted circulars promising free beer to patrons of Bruce and Stewart’s saloon “just outside of the wire.” Miners would find more than free beer at the off-limits saloon. They would also find labor organizers from back east. But Thurber security guards discovered Stewart, beat him, and put him “just outside of the wire.”

Despite Colonel Hunter’s efforts, on June 4, the Gazette reported, seven hundred Thurber men were on strike because of the wage reduction. Other miners were expected to join the strike.

In early June some Italian miners in two mines told W. K. Gordon that outsiders had warned them that if the Italian miners continued to work without an increase in wages they would be murdered.

Miners reported that in the anonymous darkness of the mines men whom they could not see or identify had threatened them.

The company began trying to recruit hundreds of replacement miners from around the country and Mexico. But men were hesitant to work as scabs during a strike.

Colonel Hunter said two hundred striking miners had been “shooting around and damaging the property,” intimidating replacements, and demanding a wage that would result in the company operating at a loss.

Colonel Hunter was determined to keep Thurber’s miners (1) on the job and (2) ununionized. A former Erath County sheriff said of Hunter: “People feared Colonel Hunter and he usually had his way in all things.”

So, just as Colonel Hunter had done in 1888 and 1890, he asked the Texas adjutant general to send Texas Rangers to Thurber to keep the peace. Captain William Jesse McDonald, of apocryphal “one riot, one Ranger” fame, was dispatched with a small detachment. (Photo from Hardin-Simmons University Library.)

Hunter also managed to get at least two of his employees, including Captain William Lightfoot of Fort Worth, commissioned as special officers of the Texas Rangers assigned to Thurber. Hunter also hired ex-Rangers, among them brothers Ed and Grude Britton, to work at Thurber. Ed was weighmaster. Grude ran one of the Thurber saloons before moving to Fort Worth to run the bar in the Metropolitan Hotel and be shot to death—while walking with Captain Lightfoot—by a police officer.

In June 1894 Texas Miner reported that “enemies of the company” had been meeting with Thurber miners in the “dive . . . just off the company property . . . where free beer is served with a lavish hand.”

Captain Lightfoot—“one of the shrewdest detectives in Texas,” Texas Miner wrote—spent a week undercover in Bruce and Stewart’s saloon, learning of the agitators’ plans to persuade the miners to strike.

One night the “outsiders” and some Thurber miners held a meeting—on company property—and Lightfoot was in attendance undercover, posing as a labor organizer. Agitators told the Thurber miners in attendance that if they struck, they would have the support of “barrels of money and a thousand men.”

At Lightfoot’s signal the building was surrounded, and the agitators were arrested by Thurber security guards.

Captain Lightfoot was promptly accused of rape by the wife of one of the men arrested but was later no-billed by a grand jury.

In another incident in June, Texas Miner reported that William Whittaker, “an aged man living just outside the company property” who was “a rantankerous [sic] agitator,” met with other men to conspire to blow up one of the mines unless the miners struck. But Captain Lightfoot was also at that meeting, and Whittaker was arrested by Texas Rangers and company guards.

Hunter blamed Bruce and Stewart for much of the labor unrest in Thurber in 1894, accusing Bruce and Stewart of plying the miners with strong drink and strong words against Hunter and his coal company.

W. K. Gordon said, “The only men from whom I hear any dissatisfaction are the parties who have been frequenting Bruce and Stewart’s saloon.” Gordon said, “I have frequently passed Bruce and Stewart’s and seen miners lying around the saloon . . . in a state of beastly intoxication.”

After nosing about a few days Texas Rangers Captain McDonald agreed with Hunter and Gordon: He reported to Austin that most of the dissatisfaction seemed to be coming from Bruce and Stewart’s saloon.

But McDonald did attend one meeting of miners where the fiery rhetoric alarmed him. The meeting was held off company property. One speaker told the assembled miners that they should dynamite the mines and get rid of Colonel Hunter. Upon hearing that, McDonald addressed the men: “As you all know, I’m Captain Bill McDonald of the Texas Rangers. The acts that you men are contemplating are unlawful, and I will jail any man who carries out this criminal action.”

The crowd dispersed.

The next day a group of miners approached McDonald and asked if Thurber’s miners would be protected if they returned to the mines.

McDonald said yes, and the miners returned to work.

According to Harold J. Weiss Jr.’s biography of McDonald, Yours to Command, Colonel Hunter praised McDonald as a “brave and efficient officer” who prevented “bloodshed” at Thurber.

On June 20 McDonald was in Fort Worth, where he reported that “all was quiet at the Thurber mines.”

Meanwhile, after eight weeks the nationwide miners strike ended, the miners’ wage demand largely unmet. During the strike at least five people had been killed as striking miners clashed with nonstriking miners, mine company security guards, law enforcement officers, and National Guard troops.

I can find no newspaper reports about the outcome of the legal case against “avengers” Grant, Bruce, and Stewart for mailing the threatening letter to Colonel Hunter. But Bruce, at least, was a free man in October 1894, when he was found guilty of violating liquor laws in Parker County. By the end of 1894 he had moved to Dallas, where he owned a wholesale wine and liquor business.

Two years later a verdict in the other court case—brought by Bruce and Stewart against Hunter for maliciously discouraging patronage of Bruce and Stewart’s saloon—was returned. The “avengers” were awarded $1, just five zeroes short of the sum they had asked.

By 1896 the labor unrest and beer foam had settled, and life both above and below ground went on at Thurber. This Texas General Land Office map of 1896 shows southern Palo Pinto County and northern Erath County. The main spur from the Texas & Pacific railroad track ran south to Thurber, where branch spurs ran to outlying mines on which miners rode the Black Diamond train. (According to John S. Spratt Sr. in his Thurber, Texas, the nearby town of Gordon in southern Palo Pinto County is named for civil engineer H. L. Gordon, not civil engineer W. K. Gordon.)

Thurber in 1898.

In 1899 Colonel Robert Dickie Hunter retired. But his right-hand man, William Knox Gordon, continued as superintendent of Texas & Pacific Coal Company.

Hunter in his retirement remained in Fort Worth and organized the Hunter-Phelan Savings and Trust Company, housed in the 1905 Atelier Building on West 8th Street (next to the Barber’s Bookstore building).

These people were posing in front of Thurber mine no. 8 in 1901. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

In 1902 Colonel Robert Dickie Hunter died in his home on Quality Hill. He was buried in St. Louis.

The next year, 1903, was a momentous one for William Knox Gordon and Texas & Pacific Coal Company. In February Gordon was married.

And in September the miners of Thurber went on strike as the United Mine Workers union tried to unionize southern mines.

When the strike began, just as Colonel Hunter had done in 1888, 1890, and 1894, W. K. Gordon asked Austin to send Texas Rangers to Thurber. Dispatched by Adjutant General John Augustus Hulen (who would later live on Elizabeth Boulevard), Captain John E. Rogers and four Rangers arrived before Labor Day (September 7), which was when Gordon expected United Mine Workers representatives to attempt to unionize the Thurber miners. The miners struck on September 9.

Thurber’s striking miners demanded the right to unionize, a wage increase, a shorter workday, and dismissal of armed guards and Texas Rangers.

Oh, and the miners made one more demand of Texas & Pacific Coal Company: “the wire”—the barbed-wire fence that symbolized the company domination over the workers—must come down.

On September 12 the Telegram reported that striking miners were leaving Thurber and that Captain Rogers and his four men were keeping the peace. W. K. Gordon told the miners that the wage increase they demanded would bankrupt the company.

Note that the report mentions the town of Grant, which had grown from Jimmy Grant’s relocated saloon during the 1894 turmoil.

But something made the strike of 1903 different than the strikes of 1888 and 1894: The Colonel was no longer around. His protégé, William Knox Gordon, and company president Edgar L. Marston were negotiating with the union. Gordon and Marston were not as vehemently opposed to unions as Hunter had been.

In a change of heart that would have given the Colonel a heart attack, Texas & Pacific Coal Company met the strikers’ demands.

American Federation of Labor negotiator C. W. Woodman declared: “The company now recognizes the union.”

After decades of company-employee turmoil, Thurber was unionized. In fact, Thurber became known as the only 100 percent closed-shop city in America.

Oh, and “the wire” came down.

The agreement ending the strike and allowing workers to unionize was signed in the (original) Worth Hotel in Fort Worth. Miners and their families began moving back to Thurber.

(About those job names: As a string of cars loaded with coal was hauled from a mine to an elevator, a spragger uncoupled each car. As each car was loaded onto the elevator, a trapper triggered a trap that held the car securely on the elevator during its ride to the surface.)

Soon after the strike ended, Texas Rangers Captain Rogers said he had not been called upon to put down any violence at Thurber. He praised the striking workers as orderly. In fact, Don Woodard in Black Diamonds! Black Gold! writes that the Rangers passed the time by pitching horseshoes, playing mumblety-peg, and cleaning their pistols. Note that Captain Rogers met with Texas Rangers Captain Sam McMurry, who had been dispatched to Thurber in 1888 and 1890.

Meanwhile, W. K. Gordon suffered a loss in his personal life two years later when his infant daughter died.

Panoramic photo of Thurber in 1911. The unidentified man in the vest may be W. K. Gordon. (Photo from Grace Museum.)

Sanborn map of 1911 shows the overall layout of the mines, the town, and the junction of the Thurber spur and the Texas & Pacific railroad track.

Sanborn map of 1911 shows a section of the town of Thurber. The map notes the population of Thurber at four thousand.

In 1919 the W. K. Gordon family suffered another loss as daughter Louise drowned.

Thurber’s coal mining operation peaked around 1920. But by then railroads—Thurber’s main customer—were switching from coal to oil (see Part 3) as fuel for locomotives. Natural gas was competing with coal for heating fuel. Demand for coal was down. By 1921 the T&P railroad bought so little coal that Thurber was forced to end its contract with the unions. The company refused to pay the higher wages demanded by the unions. The union miners went on strike.

By September 1921 the miners had been on strike five months. W. K. Gordon was pessimistic: “It looks as though we would remain closed indefinitely.” Note that Gordon had been promoted to vice president of the company.

Gordon’s pessimism was well founded. In 1921 the mines closed. Thurber, as first the largest company town in Texas and then as the only 100 percent closed-shop city in the country, had produced thirteen million tons of coal in its lifetime.

By 1940 it would be a ghost town.

Despite occasional drama such as the threat by the “avengers,” Thurber’s labor relations during thirty-five years had been relatively benign. Marilyn D. Rhinehart in her A Way of Work and a Way of Life writes: “Despite the years of labor agitation in a frontier setting, where the use of a rifle was second nature, no pattern of violence among coal miners existed to set the stage for an explosive showdown at Thurber.”

By the time the mines closed, the company would have a new name—“Texas Pacific Coal and Oil Company”—that reflected its new—and lucrative—product (see Part 3). That new product gave the company less incentive to continue mining coal.

In 1923 William Knox Gordon resigned from the company and moved to Fort Worth. Ex-Texas Ranger Ed Britton became superintendent.

Meanwhile, Thurber may have closed its coal mines and lost W. K. Gordon, but the second natural resource that Gordon had helped to coax from the winding, barren hills of the Erath Mountains continued to be paydirt.

Paydirt and the Man from Spotsylvania (Part 2): Shale

(Thanks and a tip of the miner’s helmet to Donna Humphrey Donnell for her help.)