William Knox Gordon was trained as a civil engineer, but, his son later recalled, Gordon was keenly interested in geology. On the day Gordon arrived in Erath County in 1889 he spent hours exploring “the winding, barren hills” of the Erath Mountains (see Part 1), studying the terrain, according to Don Woodard in Black Diamonds! Black Gold!: The Saga of Texas Pacific Coal and Oil Company.

Fast-forward to about 1896.

“While he was walking one day in the rain,” Gordon’s son recalled, “he got mud on his boots. . . . He studied the mud and burned it. It looked as if it would make brick. He or Colonel [R. D.] Hunter sent a sample to a laboratory in St. Louis. The report came back positive.”

That “mud” was actually shale on the property of Texas & Pacific Coal Company at Thurber, and the test report showed that humble mud was suitable for making drain tile, roof and floor tile, and dry-pressed and vitrified brick.

Paydirt!

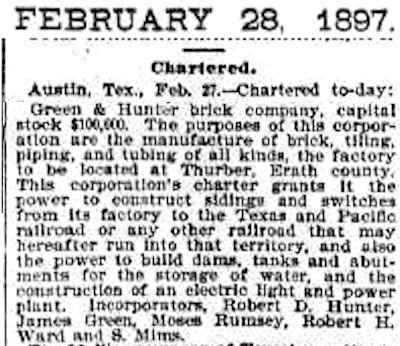

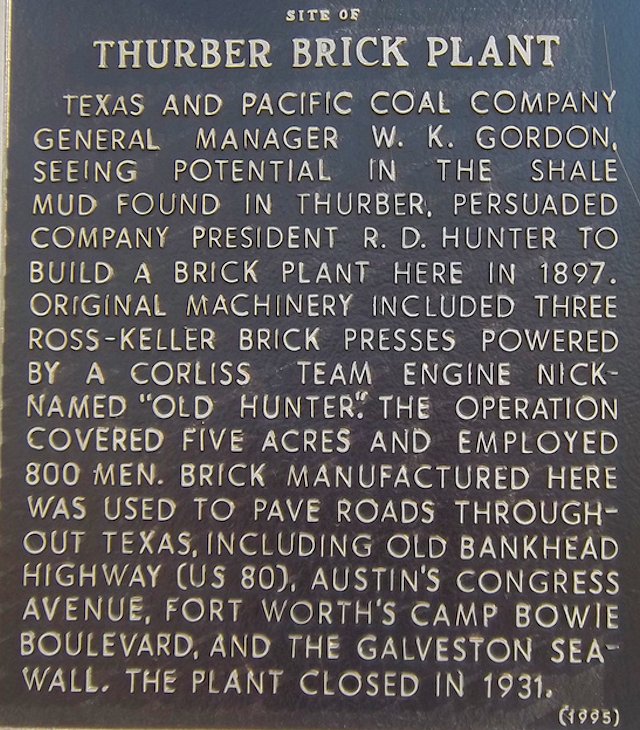

Eager to extract a second natural resource from the Erath Mountains, in 1897 Texas & Pacific Coal Company president Colonel Robert Dickie Hunter chartered, with St. Louis friend James Green, Green and Hunter Brick Company.

Eager to extract a second natural resource from the Erath Mountains, in 1897 Texas & Pacific Coal Company president Colonel Robert Dickie Hunter chartered, with St. Louis friend James Green, Green and Hunter Brick Company.

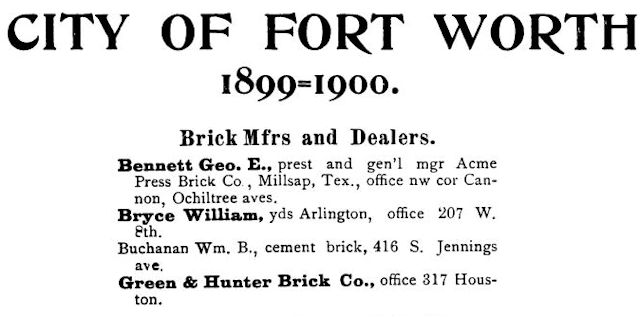

The brick company, like the coal company, was headquartered in Fort Worth. In the beginning the brick company was not part of the coal company.

The brick company, like the coal company, was headquartered in Fort Worth. In the beginning the brick company was not part of the coal company.

The brick plant at Thurber covered five acres, produced seventy-five thousand bricks a day, and employed eight hundred men. Much of the work was done by machinery, but some of the work was done manually, one brick at a time. The shale was dug out of a hillside by a thirty-ton steam shovel that moved along sections of railroad track. When the shovel reached the end of its track, the shovel simply picked up the section of track that was now behind it and placed the section down in front of it and moved on. The shovel dumped the shale into cars, which were hauled to the plant, where the shale was ground into a fine grit, mixed with water to form a stiff mud, sliced by wire knives into “green brick” of the desired shape, and moved to dryers and then to kilns—really big kilns—for firing.

In the beginning the kilns were fueled by pea coal dug by Thurber’s miners. And that coal didn’t cost the company a dime: The company paid its miners for digging only large chunks of coal.

After firing, finished bricks were loaded onto railroad boxcars for delivery.

(Watch a silent documentary on the Thurber brick plant.)

The brick plant in 1898. After the brick plant opened, the company began to replace Thurber’s wooden buildings with brick buildings. Some housing for employees was built with rejected bricks.

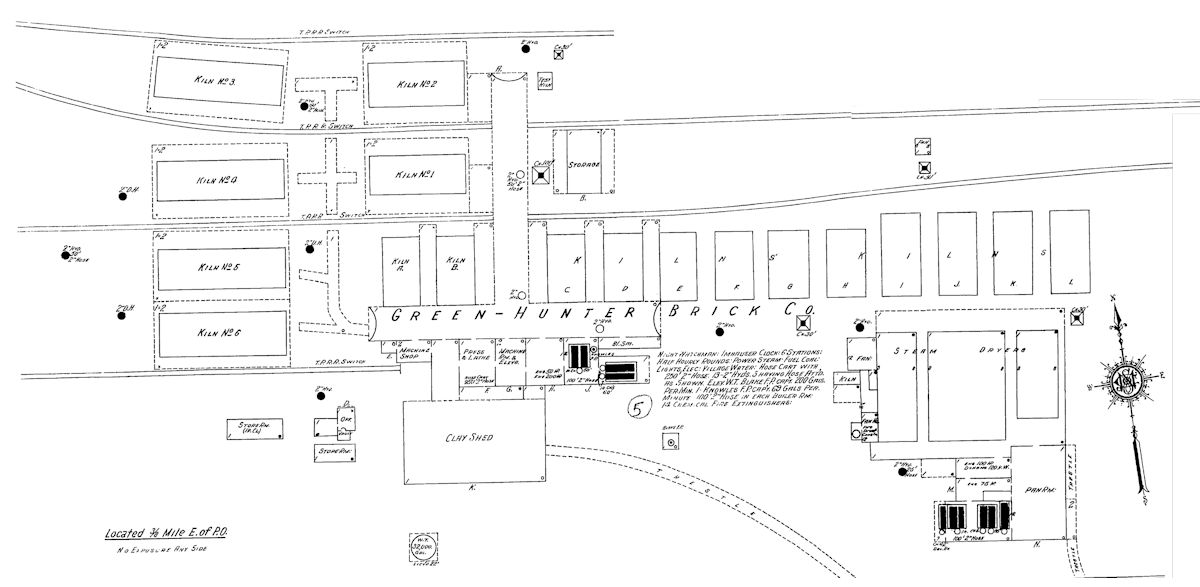

A diagram of the brick plant.

A diagram of the brick plant.

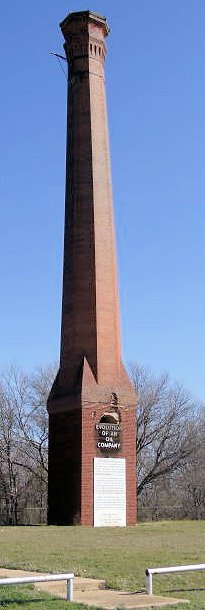

In 1908 Thurber built a new electric power plant. Powered by coal, naturally. While building that power plant Thurber also built itself a skyline and a monument to its brickworks: The power plant’s brick smokestack is 128 feet tall. It replaced a smokestack built in 1898 that was 160 feet tall. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

In 1908 Thurber built a new electric power plant. Powered by coal, naturally. While building that power plant Thurber also built itself a skyline and a monument to its brickworks: The power plant’s brick smokestack is 128 feet tall. It replaced a smokestack built in 1898 that was 160 feet tall. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

If you have been in Texas long, chances are good that you have trod on Thurber bricks.

If you have been in Texas long, chances are good that you have trod on Thurber bricks.

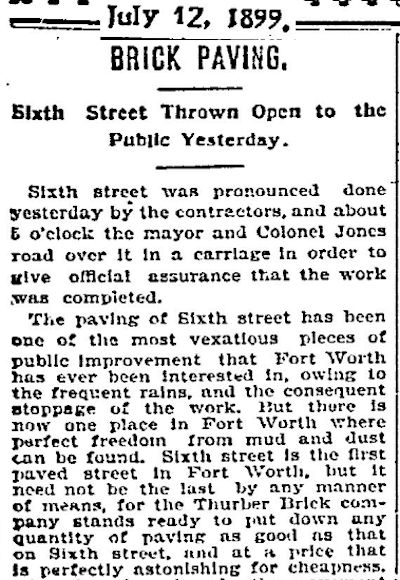

For example, in 1899 Thurber bricks were laid on West 6th Street, “the first paved street in Fort Worth” and one of the first brick-paved streets in Texas.

In 1900 Texas & Pacific Coal Company absorbed Green and Hunter Brick Company. By 1902 (when Colonel Hunter died) the brick company also was referred to as “Thurber Brick Company.” The Thurber Brick Company competed with Acme Brick Company, founded by George Bennett in 1891 in Parker County, and the Cobb brothers’ brick plant, founded in 1907 on Sycamore Creek.

Thurber bricks—millions of them—built the Stockyards and packing plants. This brick is on the Swift property.

Thurber bricks—millions of them—built the Stockyards and packing plants. This brick is on the Swift property.

Brick floor in Stockyards Station (originally the hog and sheep pens) on East Exchange Avenue.

Brick floor in Stockyards Station (originally the hog and sheep pens) on East Exchange Avenue.

The Thurber brand is stamped on this brick at the Stockyards.

The Thurber brand is stamped on this brick at the Stockyards.

The Thurber brand is embossed (raised) on this brick at the Stockyards. The triangle containing the letters B, T, and T (for “Brick, Tile and Terra Cotta Workers’ Alliance”) is the mark of the union and appears on “newer” bricks—those made after Thurber workers unionized in 1903.

The Thurber brand is embossed (raised) on this brick at the Stockyards. The triangle containing the letters B, T, and T (for “Brick, Tile and Terra Cotta Workers’ Alliance”) is the mark of the union and appears on “newer” bricks—those made after Thurber workers unionized in 1903.

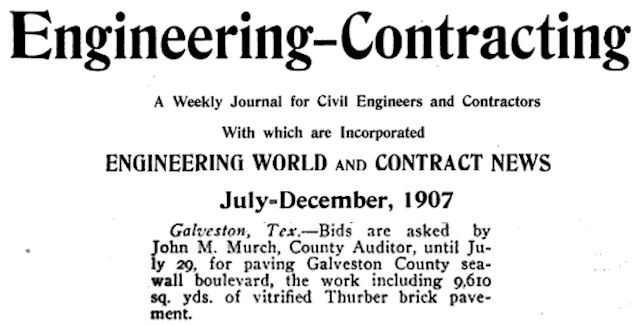

After the hurricane of 1900, Thurber provided the bricks for Galveston’s seawall and the boulevard along the seawall.

After the hurricane of 1900, Thurber provided the bricks for Galveston’s seawall and the boulevard along the seawall.

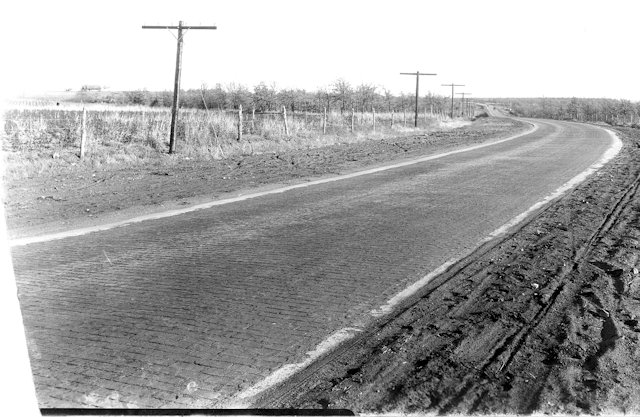

Parts of the Bankhead Highway were paved with Thurber bricks. (Photo from Boyce Ditto Public Library.)

Parts of the Bankhead Highway were paved with Thurber bricks. (Photo from Boyce Ditto Public Library.)

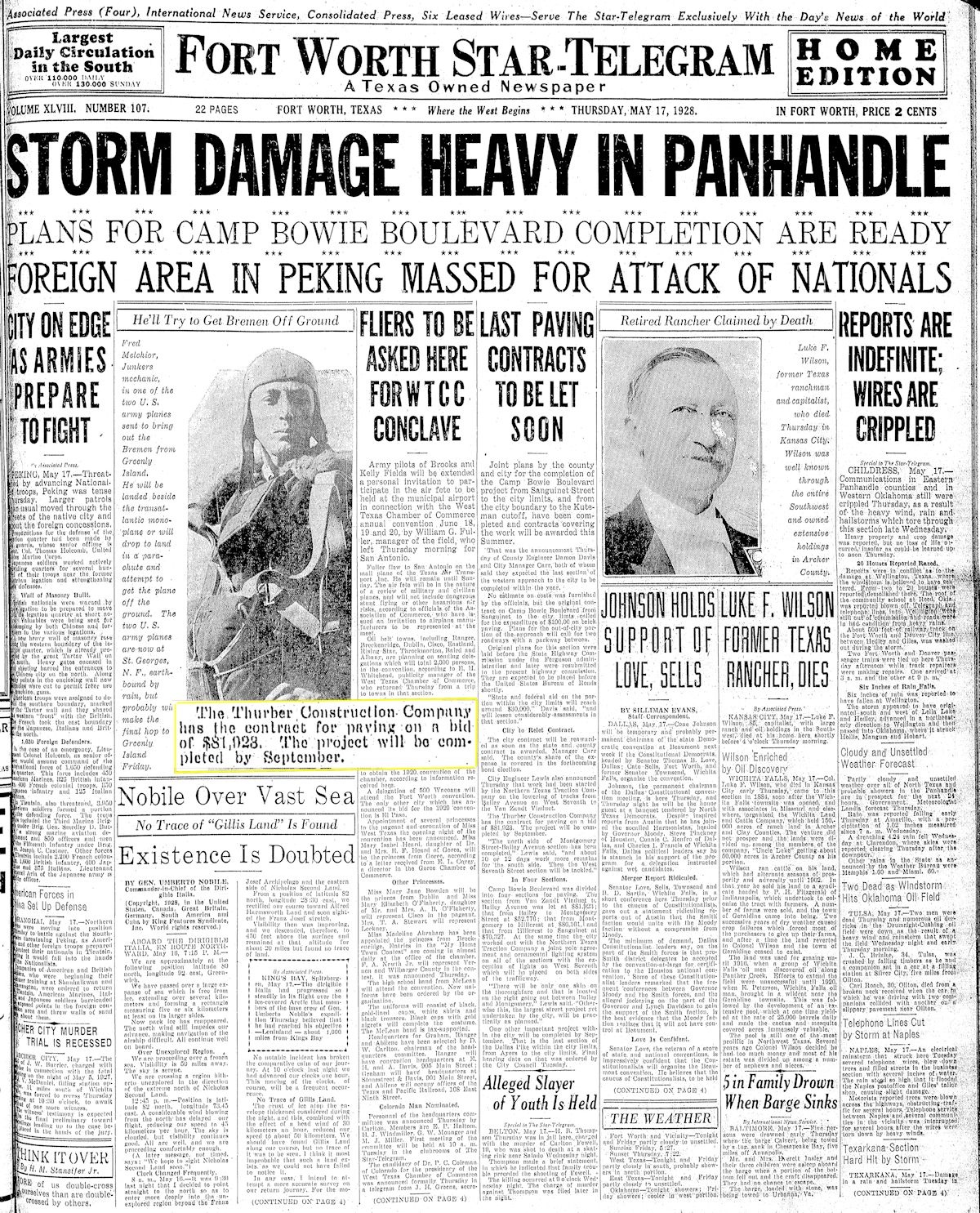

In 1927-1929 Thurber provided the bricks for Camp Bowie Boulevard (replacing creosoted wooden blocks). The paving of the street with Thurber bricks was done by—wait for it—the Thurber Construction Company. North Main, Exchange, Commerce, Daggett, south Hemphill, West 7th, and other streets in Fort Worth also were paved with Thurber bricks.

In 1927-1929 Thurber provided the bricks for Camp Bowie Boulevard (replacing creosoted wooden blocks). The paving of the street with Thurber bricks was done by—wait for it—the Thurber Construction Company. North Main, Exchange, Commerce, Daggett, south Hemphill, West 7th, and other streets in Fort Worth also were paved with Thurber bricks.

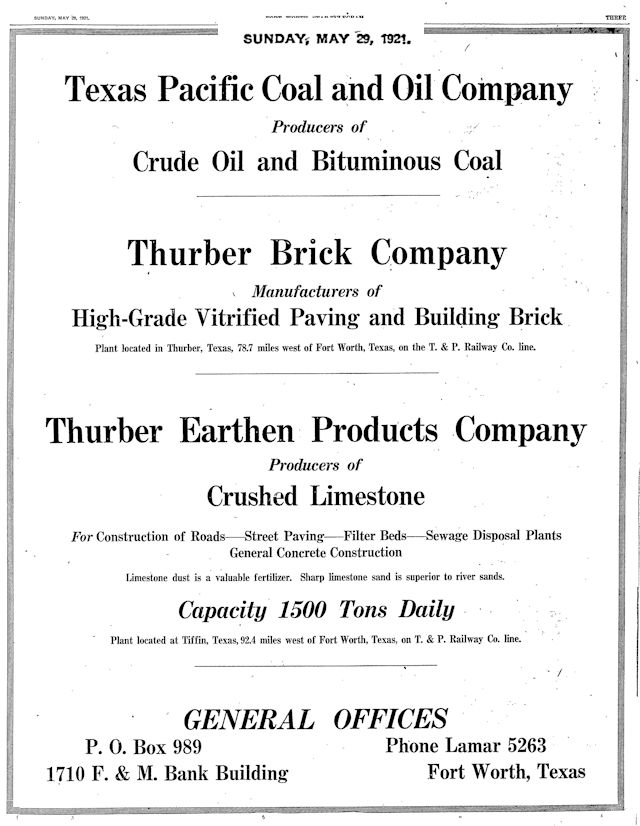

By 1921 the company also was producing crushed limestone.

By 1921 the company also was producing crushed limestone.

Thurber’s coal mines shut down in 1921, but its brick plant continued to operate. But John S. Spratt Sr. in his Thurber, Texas writes that the Great Depression of 1929 greatly reduced the demand for brick. The plant closed in 1931, putting several hundred men out of work. Spratt said the company allowed the men to continue living rent free in their company house and to receive thirty dollars in credit each month at the company store. “This [arrangement] apparently continued for several years.”

Thurber’s coal mines shut down in 1921, but its brick plant continued to operate. But John S. Spratt Sr. in his Thurber, Texas writes that the Great Depression of 1929 greatly reduced the demand for brick. The plant closed in 1931, putting several hundred men out of work. Spratt said the company allowed the men to continue living rent free in their company house and to receive thirty dollars in credit each month at the company store. “This [arrangement] apparently continued for several years.”

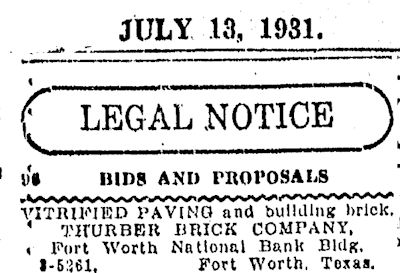

By 1931, after more than thirty years and almost a billion bricks, the company was selling off its inventory.

By 1931, after more than thirty years and almost a billion bricks, the company was selling off its inventory.

Meanwhile, W. K. Gordon, who had been superintendent of Thurber’s coal operation and the impetus behind Thurber’s brick operation, had been instrumental in converting a third natural resource in the area into paydirt.

My late dad somehow got a hold of hundreds of Thurber brinks. He and his father paved our driveway and back porch with them. I can’t give away many of them (as they are in use) but holler at me if you want some.

I have 700 or so stockyards brick we need to sell. In storage in Arlington

Leon, do the bricks you have say Thurber on them? I may want a few. Please contact me.