You might not have known their family names: Pappajohn, Phiripes, Klidas, Salicos, Sparto. You might not have seen their family farms as you drove past them on White Settlement Road or Jacksboro Highway or Beach Street. But if you lived in Fort Worth in the twentieth century you may have eaten the vegetables they grew. Perhaps you bought directly from their grocery store or their produce market or indirectly at a supermarket through a wholesaler.

They were the Greek truck farmers of the Trinity River, the first of them arriving here more than a century ago.

Greeks immigrants came to America, as did so many others from Europe, looking for a better life, even if in one case a better life meant simply riding tall in the saddle: The first Greek to settle in Fort Worth was Demetrios Anagnostakis. Anagnostakis, who read Zane Grey novels, arrived in Cowtown in 1893 with spurs in his eyes: He wanted to be a cowboy. As close as he got was a job tending cattle in the pens at the stockyards.

Many Greek immigrants arriving after Anagnostakis, especially after 1902, followed in his bootprints: They worked at the stockyards and especially the packing plants. Like other immigrants, the Greeks formed an enclave for their mutual support. That enclave was located on North Calhoun and North Jones streets at Central Avenue—walking distance to the packing plants.

Most of the first Greek immigrants were men. Some planned to save enough money to bring their family to America. Others married a local woman and started a family here from scratch.

Few of the immigrants regarded a job at the packing plants as a lifelong career. Some Greeks saved their money and opened small businesses such as bakeries and restaurants. For example, in 1921 Greek immigrant George Koutsoubos opened the restaurant that would evolve into Famous Hamburgers, the walk-up eatery that operated for decades at the corner of Main and East 1st streets.

The Greeks clung to their native language and religion, food (head cheese, moussaka, baklava) and customs even as they blended with their adopted culture. Each succeeding generation was more assimilated. The first-generation immigrants might speak only Greek or fractured English. Their grandchildren might speak only English.

Many Greeks arriving early in the twentieth century were fleeing ethnic and religious oppression of Christian Greeks by Turks of the Ottoman empire. To keep their religion alive, in 1910 Fort Worth’s Greeks chartered St. Demetrios Greek Orthodox Church—the first Greek Orthodox church in Texas. At first the congregation worshipped in rented space downtown. Then it bought a modest wooden building. In 1917 the congregation laid the cornerstone of a fine brick church building, designed by L. B. Weinman, at 2022 Ross Avenue near the packing plants. Services were held almost entirely in Greek. The current St. Demetrios church is located at 2020 Northwest 21st Street near Jacksboro Highway.

Many Greeks arriving early in the twentieth century were fleeing ethnic and religious oppression of Christian Greeks by Turks of the Ottoman empire. To keep their religion alive, in 1910 Fort Worth’s Greeks chartered St. Demetrios Greek Orthodox Church—the first Greek Orthodox church in Texas. At first the congregation worshipped in rented space downtown. Then it bought a modest wooden building. In 1917 the congregation laid the cornerstone of a fine brick church building, designed by L. B. Weinman, at 2022 Ross Avenue near the packing plants. Services were held almost entirely in Greek. The current St. Demetrios church is located at 2020 Northwest 21st Street near Jacksboro Highway.

For more than a century St. Demetrios church has been the religious and social center of the Greek community—bake sales, dances, weddings, baptisms, funerals.

As some of the Greek immigrants passed through New York Harbor bound for Ellis Island and eventually Fort Worth early in the twentieth century, they saw in Lady Liberty’s hands not a torch and a tablet but a hoe handle and a seed packet. These immigrants had been farmers in the old country and yearned to be farmers again in their adopted country.

Oh, initially many of them took jobs at the packing plants. But they saved their wages to buy mules and plows to farm as tenants. They kept saving until they could buy their own farm.

The climate of their new home reminded them of the old country: mild winters, hot, dry summers, and a long growing season.

Early in the twentieth century most of Fort Worth was south of the river. North of the river plenty of undeveloped land remained, especially along the Trinity River. The Greek truck farmers bought land along the river for three reasons:

- The river provided water for irrigation. The property line of the Greek farmers extended to the middle of the river channel, and they had riparian rights to pump as much water as they wanted.

- The land was cheap. Why was it cheap? Because it was prone to flooding (1908, 1922, 1949).

But that flooding brings us to the third reason for farming land along the river:

- Its floodplain was fertile. Centuries of flooding had deposited tons of rich sandy loam silt.

Thus the farmers had a love-hate relationship with the river. Floods had made the land along its banks fertile. But floods also could wipe out a farmer’s crop, especially before the river was constrained by the floodway in the 1950s and 1960s.

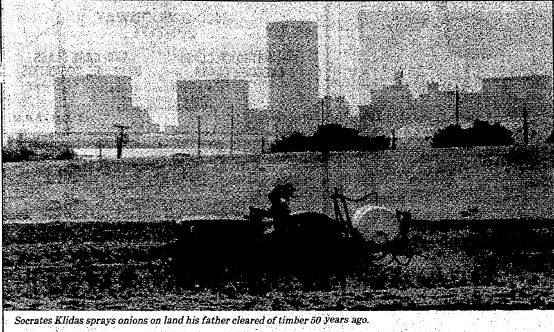

The Greek farmers of the floodplain could look south across the river at the growing skyline of downtown Fort Worth, look north at the bustling, bawling stockyards-packing plants area where they once worked.

Farming for the Greeks was a family enterprise. Their children were driving tractors when most of their classmates were learning to ride bicycles. And farming was a tradition, handed down from generation to generation for decades.

J’Nell Pate writes in North of the River that by the 1930s about seventy-five percent of the Greeks in Fort Worth were truck farmers. (The word truck in truck farm has nothing to do with motor vehicles. The motor vehicle truck comes from the Greek word trochos meaning “wheel.” The truck in truck farm comes from the Old French word troque meaning “barter.”)

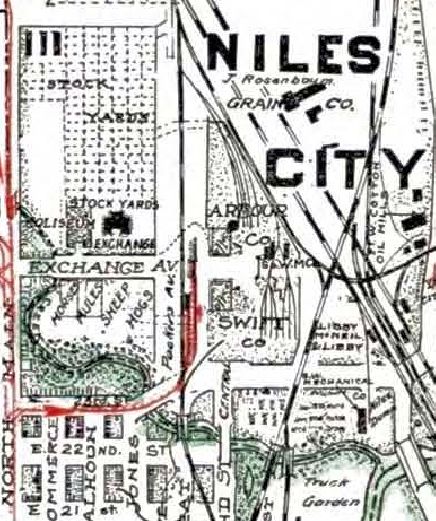

A 1919 map of the North Side shows a large truck garden just south of the Swift packing plant at the confluence of the Trinity River and Marine Creek. Adjacent to the truck garden was the sewage treatment plant of the packing plants. Was the garden fertilized by sludge from that plant?

A 1919 map of the North Side shows a large truck garden just south of the Swift packing plant at the confluence of the Trinity River and Marine Creek. Adjacent to the truck garden was the sewage treatment plant of the packing plants. Was the garden fertilized by sludge from that plant?

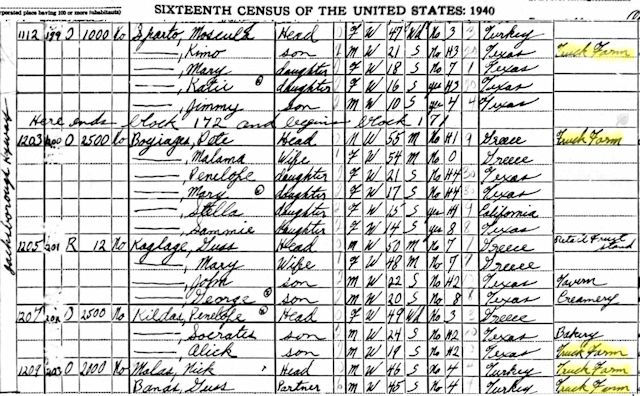

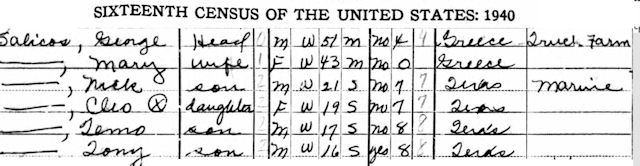

Many Greeks who farmed along the river lived on nearby streets: Jacksboro Highway, Terrace Avenue, White Settlement Road, Ohio Garden Road. For example, the 1940 census lists five truck farmers—three of them born in Turkey or Greece—living in the first two blocks of Jacksboro Highway north of the river.

Many Greeks who farmed along the river lived on nearby streets: Jacksboro Highway, Terrace Avenue, White Settlement Road, Ohio Garden Road. For example, the 1940 census lists five truck farmers—three of them born in Turkey or Greece—living in the first two blocks of Jacksboro Highway north of the river.

In 1952 the triangle bounded by the river, North University Drive (left), and Jacksboro Highway (right) was farmland. Oakwood Cemetery is in the upper right.

In 1952 the triangle bounded by the river, North University Drive (left), and Jacksboro Highway (right) was farmland. Oakwood Cemetery is in the upper right.

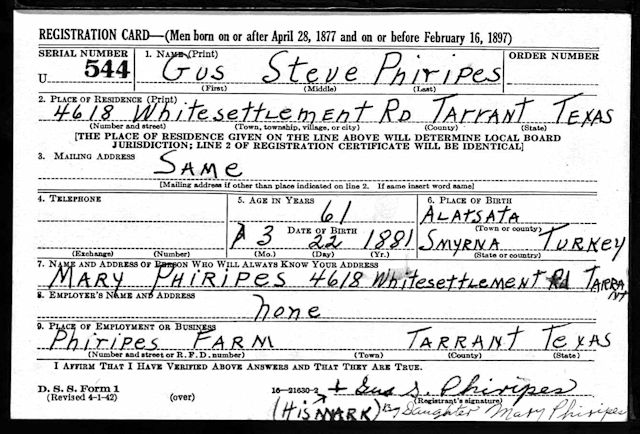

Among the first of the Greek farmers was Gus Phiripes, an ethnic Greek who was born in Turkey in 1881 and passed through Ellis Island sometime between 1910 and 1916. He got a job at the Swift packing plant and married Katherine Spinos, herself a Greek immigrant. Gus and Katherine’s son George was born in Niles City.

In 1914 Gus bought eight acres on the river off Cold Springs Road on the Samuels Avenue peninsula. He worked the land barefoot.

In 1922 Gus bought twelve acres on White Settlement Road.

Although past sixty years of age during World War II, Gus registered for the draft in his adopted country. On this card he made his X mark beside his name, written by daughter Mary.

Although past sixty years of age during World War II, Gus registered for the draft in his adopted country. On this card he made his X mark beside his name, written by daughter Mary.

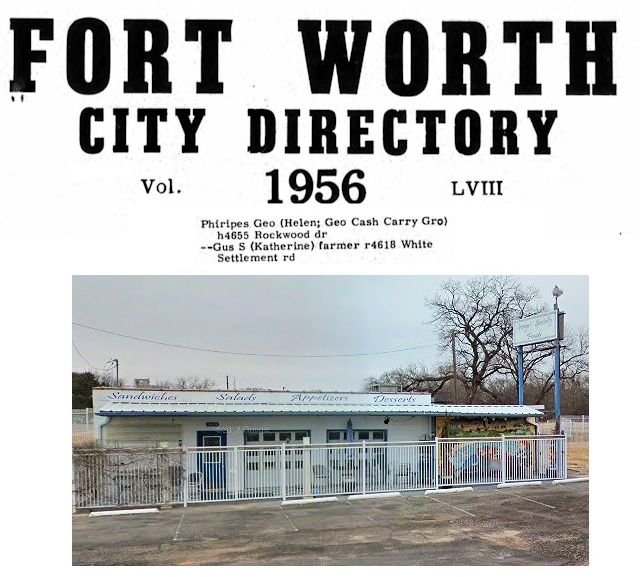

In 1951 the Phiripes family opened George’s Cash and Carry store at 4424 White Settlement Road. For forty-eight years son George sold the farm’s produce in addition to dry goods: mustard greens, beets, onions, peppers, eggplant. The store evolved into George’s Imported Foods, stocking eight varieties of Greek wine, eight brands of olives, fifteen brands of Mediterranean olive oil. And cheeses from Greece, Italy, Cyprus, Israel, Bulgaria, and Switzerland.

In 1951 the Phiripes family opened George’s Cash and Carry store at 4424 White Settlement Road. For forty-eight years son George sold the farm’s produce in addition to dry goods: mustard greens, beets, onions, peppers, eggplant. The store evolved into George’s Imported Foods, stocking eight varieties of Greek wine, eight brands of olives, fifteen brands of Mediterranean olive oil. And cheeses from Greece, Italy, Cyprus, Israel, Bulgaria, and Switzerland.

About three miles downstream from the Phiripes farm, near Oakwood Cemetery, was the farm begun by Jim Klidas, an ethnic Greek born in Turkey in 1880. In 1980 son Socrates Klidas told the Star-Telegram that his father had cleared the land of timber and began farming it in the 1920s. The Klidas farm, Socrates said, was “just two miles as the crow flies from the county courthouse.”

About three miles downstream from the Phiripes farm, near Oakwood Cemetery, was the farm begun by Jim Klidas, an ethnic Greek born in Turkey in 1880. In 1980 son Socrates Klidas told the Star-Telegram that his father had cleared the land of timber and began farming it in the 1920s. The Klidas farm, Socrates said, was “just two miles as the crow flies from the county courthouse.”

From the Klidas farmhouse Socrates’s wife Ernestine could see the big revolving clock atop Continental National Bank. She used that clock to time stews and meatloafs, and the family used the clock to know when to come in from the fields for lunch.

Socrates recalled: “It was hard getting started. . . . That first winter me and my father and my brother spent digging up pecan and oak trees this big around” he said, spreading his arms as far as he could. “Back then there weren’t any bulldozers. We had to dig a hole around the tree, cut off as many roots as we could, hitch up a team of horses or mules, and we pulled ’em out.”

The Klidas farm had twenty-seven acres in greens, peppers (including jalapeno), beets, and onions.

When the river was widened in the 1950s the farm lost a few acres.

Socrates described how the family processed a typical crop: Onions were picked, tied in small bundles, washed, packed four dozen bundles to a crate, and trucked to a wholesale warehouse for distribution to local supermarkets.

Farther downstream, around two lazy loops in the river, was the farm of George Salicos, born in Greece about 1889. He arrived on the North Side in 1912 and soon got a job at a packing plant. Then he rented farmland until the 1930s. By then Salicos, like Gus Phiripes, could afford to buy eight acres on the Trinity River near Samuels Avenue. Salicos and wife Mary and children lived on his farm, drilled a well, and irrigated from the river. Even during the Depression the family had plenty to eat and to sell.

Farther downstream, around two lazy loops in the river, was the farm of George Salicos, born in Greece about 1889. He arrived on the North Side in 1912 and soon got a job at a packing plant. Then he rented farmland until the 1930s. By then Salicos, like Gus Phiripes, could afford to buy eight acres on the Trinity River near Samuels Avenue. Salicos and wife Mary and children lived on his farm, drilled a well, and irrigated from the river. Even during the Depression the family had plenty to eat and to sell.

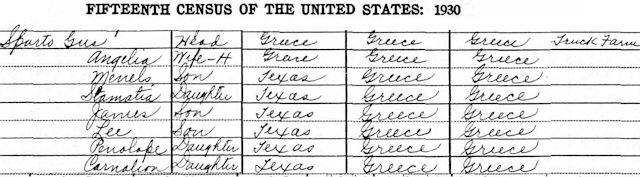

Sitheris “Jim” Sparto, born in Greece in 1894, came to America in 1912. His brother Gus, who was already here, helped Jim get a job at the Swift packing plant. Jim worked hard and saved his money. He met another Greek immigrant, Moscola Vloitos, who had come to America to live with her two brothers in 1916. Jim and Moscola married and rented farmland near White Settlement Road. Later the Spartos bought land on the river south of Oakwood Cemetery.

Sitheris “Jim” Sparto, born in Greece in 1894, came to America in 1912. His brother Gus, who was already here, helped Jim get a job at the Swift packing plant. Jim worked hard and saved his money. He met another Greek immigrant, Moscola Vloitos, who had come to America to live with her two brothers in 1916. Jim and Moscola married and rented farmland near White Settlement Road. Later the Spartos bought land on the river south of Oakwood Cemetery.

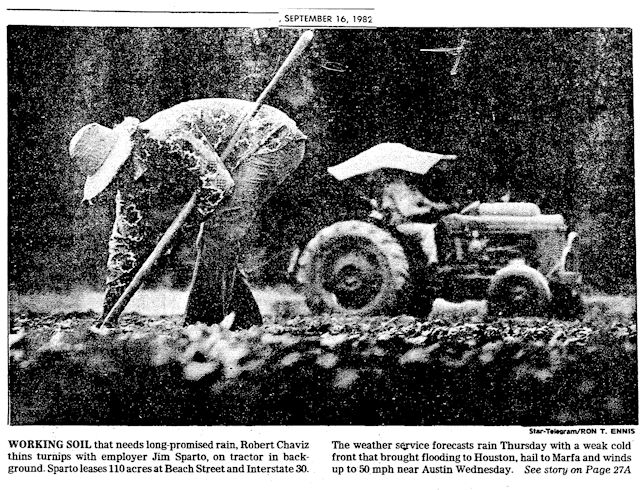

Four of Gus’s sons and a son-in-law also farmed 110 acres on Beach Street at Interstate 30. They leased the land from the Tarrant County Water Board.

Four of Gus’s sons and a son-in-law also farmed 110 acres on Beach Street at Interstate 30. They leased the land from the Tarrant County Water Board.

Gus’s son James enjoyed advances in farming technology that Gus and Jim might have envied, such as an air-conditioned tractor with cigarette lighter, power steering, radio, and seat belts.

“Being a farmer in the city is just like being a plumber or an electrician in the city,” James told the Star-Telegram in 1980. “You get up and go to work. Only you don’t have as far to commute as a lot of people.”

He pointed out another advantage of farming in the city: “You’ve got more people here you can hire, like high school kids. And you’re closer to equipment and fuel.”

Sparto suspected that even city noise is a boon to farming: The traffic noise of nearby I-30 scared away insect pests.

For many years the Spartos sold their produce—okra, onions, mustard greens, carrots, and beets—at a farmers market on Jones Street downtown. The Spartos farmed their land until the 1980s. The Beach Street farm is now part of the western extension of Gateway Park.

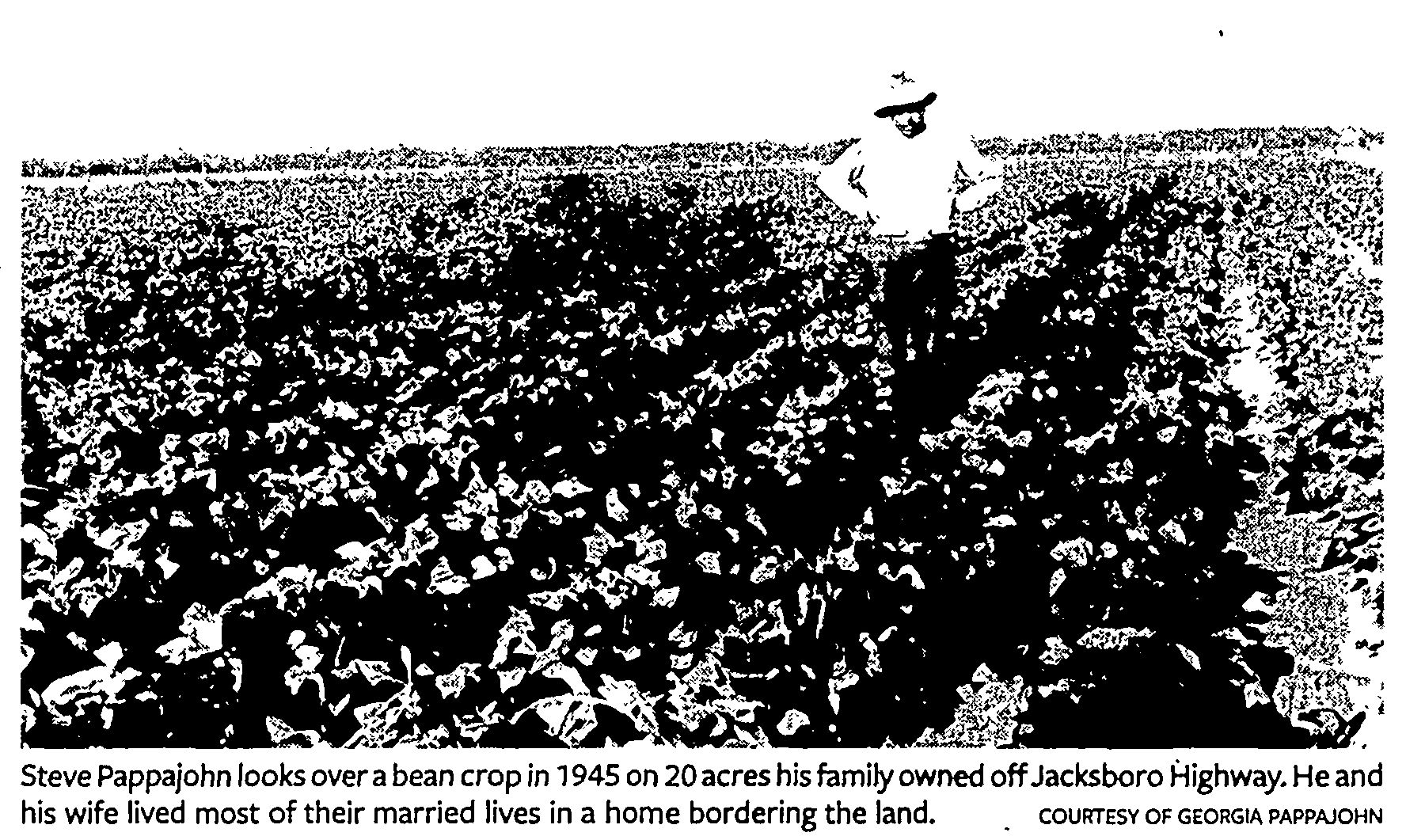

George (1880-1959) and Katy (1888-1979) Pappajohn were two more ethnic Greeks born in Turkey. They came to Fort Worth with their son Steve about 1915. George first worked for a packing plant and then rented farmland on the Trinity River. In 1934 the Pappajohns purchased their own land along the original channel of the Trinity near Rockwood golf course, just west of Jacksboro Highway on Ohio Garden Road.

George (1880-1959) and Katy (1888-1979) Pappajohn were two more ethnic Greeks born in Turkey. They came to Fort Worth with their son Steve about 1915. George first worked for a packing plant and then rented farmland on the Trinity River. In 1934 the Pappajohns purchased their own land along the original channel of the Trinity near Rockwood golf course, just west of Jacksboro Highway on Ohio Garden Road.

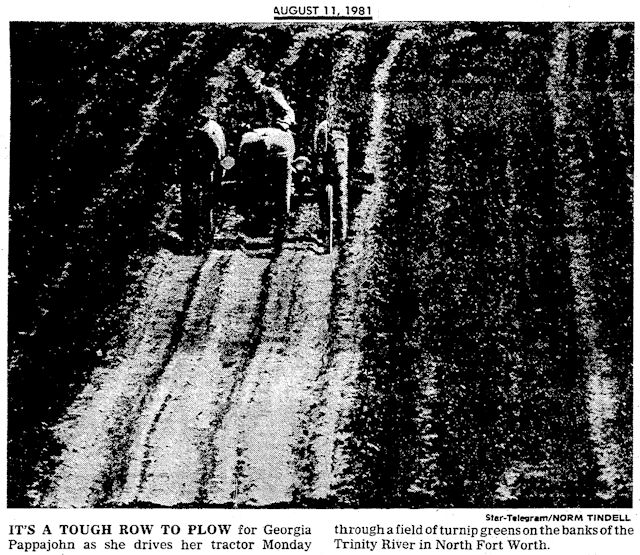

In 1945 son Steve married local girl Georgia Cole, and she fully embraced farm life and Greek life.

“There is nothing easy about farming,” Georgia told the Star-Telegram in 2007 at age eighty-four. “They don’t give you a thing on a farm except hard work,” she said.

“There is nothing easy about farming,” Georgia told the Star-Telegram in 2007 at age eighty-four. “They don’t give you a thing on a farm except hard work,” she said.

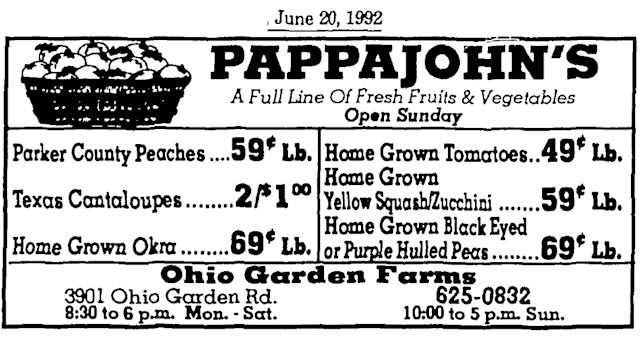

The children of Steve and Georgia—the third generation of Pappajohns—continued to truck farm in the 1990s, selling vegetables—beans, mustard greens, collard and turnip greens, sweet corn, and yellow squash—at their own produce market on Ohio Garden Road and also selling to wholesalers.

The children of Steve and Georgia—the third generation of Pappajohns—continued to truck farm in the 1990s, selling vegetables—beans, mustard greens, collard and turnip greens, sweet corn, and yellow squash—at their own produce market on Ohio Garden Road and also selling to wholesalers.

Most of the first two generations of Greek truck farmers—the immigrants and their children—are dead now. Fort Worth’s Greeks were a close community. The farmers were friends, members of St. Demetrios church. They served as best men and bride’s maids at each other’s weddings. They served as pallbearers at each other’s funerals.

Most of the first two generations of Greek truck farmers—the immigrants and their children—are dead now. Fort Worth’s Greeks were a close community. The farmers were friends, members of St. Demetrios church. They served as best men and bride’s maids at each other’s weddings. They served as pallbearers at each other’s funerals.

Rare is the third or fourth generation who embraces the passion of the first generation. Each succeeding generation of Greeks showed less interest in farming and straddling a tractor in the Texas heat.

Pate writes in North of the River that Mary Sparto, daughter of immigrants Jim and Moscola Sparto, recalled that the first generation and second generation of Greeks in Fort Worth truck farmed.

“But the third generation went to college and got other jobs,” she said.

And farming was becoming more expensive. In 1980 Georgia Pappajohn said, “Fertilizer has gone sky high, gas has gone sky high, oil has gone sky high. Insecticide has gone sky high, seed has gone up. It’s hard to keep young people on the farm. The way things are going, when I’m gone, I’m sure he [son Nick] could make more money doing about anything else.”

Son Nick said in 1980, “I just don’t see how people are going to keep raising when there’s not any more money in it than there is.”

He added: “I ought to quit eventually. But we’ve got all this equipment invested. You can’t do much of anything else with the land. It’s in the floodplain.”

Too, there were external pressures. Land in a growing city is too valuable to survive long as farmland. The Trinity River floodway allowed houses to be built closer to the river, making farmland more valuable. Some farmland was lost to the floodway. Other farmland was lost as streets were cut. Gas well drillers came knocking with fists full of dollars.

One by one the truck farms of the Trinity River disappeared under concrete and asphalt.

But one vestige of the Greek farms of the twentieth century survives. The Pappajohn family still owns its farmland, now bordered by Ohio Garden Road, a mobile home park, the original channel of the river, a gas well, and Rockwood golf course.

But one vestige of the Greek farms of the twentieth century survives. The Pappajohn family still owns its farmland, now bordered by Ohio Garden Road, a mobile home park, the original channel of the river, a gas well, and Rockwood golf course.

From the river levee the field of the Pappajohn farm can be seen beyond the Rockwood golf carts. The family’s Ohio Garden Farms produce market was housed in the building labeled “PM.”

From the river levee the field of the Pappajohn farm can be seen beyond the Rockwood golf carts. The family’s Ohio Garden Farms produce market was housed in the building labeled “PM.”

Today Nick Pappajohn, the third generation of his family to plant the fertile floodplain of the Trinity River, who almost forty years ago said, “I ought to quit eventually,” still plants fourteen acres of the Pappajohn farm—in hay.

Today Nick Pappajohn, the third generation of his family to plant the fertile floodplain of the Trinity River, who almost forty years ago said, “I ought to quit eventually,” still plants fourteen acres of the Pappajohn farm—in hay.

(Thanks to Earl Belcher for the tip.)

Back in the mid to late 70’s my family lived in a small house on Sherwood Dr. across the street from Nick. I remember when Nick Jr. was born. We moved away early in the 80’s but I remember Nick and his family.

I have found pictures of my great grandfather working his crops on White settlement road that you’re welcome to add to the page. I can attach them to an email if you’d like

The author of this site unfortunately passed last year and only recycled articles are being posted.

Georgia Pappajohn was my great aunt, and I just want to say thank you for researching and writing this. I really enjoyed reading it. I remember running around down there, through the produce stand and Christmases at her house. Her funeral was at St. Demetrios back in 2011 and we all miss her.

Two fun facts to throw in there… Paris Coffee Shop was also a Greek contribution, run by Georgia’s best friends Artemis and I believe her American husband, Mr Smith. It was later run by her son, Mike Smith until 2021. Mike only recently passed.

The other is that the made for TV movie “Finding the way Home” (1991) with George C. Scott was filmed on Aunt Georgia’s farm on Ohio Garden.

again, thank you

Thank you. The Greek farmers made a great contribution to Fort Worth.

Love this!!! I grew up right down the road from the Pappajohn farm & market and loved this family as my own growing up. My parents were friends of Steve & Nick and my older brother & I grew up and were friends with Nicks children Hailey & Nicholas. I loved loved Georgia Pappajohn and Jimmie Bakintas and Georgia Bakintas was great friends with my cousin Tonia. I spent lots of time hanging out with Hailey at the farm and market and at the house there. Not blood related, but like family & I LOVE this piece on this wonderful family and their history.

Thank you, Amanda. I really enjoyed researching the Greek farmers.

I went to work in the law offices of Willis & McEntire when I was 17, fresh out of Poly, and the first case I can remember was for the Spartos family, and they were being challenged, if I remember correctly, about taking water out of the Trinity for their truck farm, and arguing for their riparian rights! At 17, I had to look up riparian to see what it meant! Mr. Sparto was a really nice man, and we won his case!

Thanks, Shirley. The Greek farmers are a wonderful part of Fort Worth’s history. I think I was forty before I knew what riparian means.

Constantine was my great grandfather. I live in the same rock house on the original property and make my garden in the same dirt. My grandfather Steve had me on the tractor at an early age and after all these years the tractor still remains at the homestead. George’s store was my great uncles sandwich shop when growing up. It is a very humbling experience to get on the old tractor and chug around the property knowing the history. Even though I’m fourth generation, there’s something highly satisfying about watching the plows turn dirt from the seat of an old tractor and thinking about how many times ut must have been done. I really liked this article and would be happy to offer any info or answer questions.

Thank you, Steven. Your family story is a wonderful part of Fort Worth history. I so enjoyed learning it.

That’s my home….. I grew up at 3803 Ohio garden road. My father was Steve Pappajohn, my uncle is Nick Pappajohn and my grandma was Georgia Pappajohn. This literally made me cry. I know the Phirripes. I know Nick and his son Theo.The Greek community was disintegrated and it breaks my heart. I used to look forward to going to Mrs.Chumpus’ house because she was so sweet and always was happy to see me and dad come fix whatever she needed tending to around her house, usually just the odd job..trim a few tree limbs, look at her faucet leaks. I feel like my great-grandparents would be so heart broken, over how broken our family and community has befallen.

Your family and the other Greek farming families were a big part of Fort Worth in the twentieth century. I enjoyed learning and telling their story.