On a pleasant spring morning in 1934—April 1, Easter Sunday—the three remaining members of the Barrow gang—Bonnie and Clyde and Henry Methvin—waited on the side of Dove Road near the intersection of Highway 114 outside Grapevine. Clyde had arranged a get-together with the Barrow and Parker families of west Dallas at this isolated spot. Going into west Dallas to visit family was now too risky for fugitives Bonnie and Clyde. As the three waited at their parked car for the two families to arrive, Clyde slept on the back seat. Bonnie sat on the grass and played with a white rabbit she intended to give her mother as an Easter gift. Bonnie had named the rabbit “Sonny Boy.”

Henry Methvin stood guard. He was, as always, watching for the law. He also was watching for Raymond Hamilton. The hard feelings between Clyde and Hamilton had intensified since Hamilton had left the gang. Clyde knew that Hamilton had just robbed a bank and taken a mother and child hostage and might be headed for Grapevine. If Clyde saw Hamilton he intended to shoot him on sight.

Hamilton never drove past on that Easter Sunday.

But state troopers E. B. Wheeler and H. D. Murphy did. The two motorcycle officers were riding north on Highway 114 about 3:45 p.m. As they passed the intersection with Dove Road they saw the black Ford parked on the side of the road. Perhaps they thought a motorist was stranded. Perhaps they thought the car matched the description of the car that Raymond Hamilton was last seen driving.

Either way, Wheeler and Murphy doubled back and rode east on Dove Road toward the car.

When Methvin saw the two lawmen approaching he grabbed his Browning automatic rifle. Bonnie went to the car and woke Clyde, who grabbed his sawed-off shotgun and stood behind the car.

The two troopers stopped near the car and parked their motorcycles.

Clyde planned to take the two troopers prisoner. He said to Methvin: “Let’s take ’em!”

Methvin misunderstood Clyde’s intention and opened fire, shooting Wheeler in the chest. As soon as Murphy reached for his pistol, Clyde shot him. As the two troopers lay wounded on the ground Methvin shot them again with a pistol.

The troopers’ handguns were still holstered.

Bonnie and Clyde and Henry Methvin and a rabbit named “Sonny Boy” fled to Oklahoma.

Officer Wheeler, twenty-six, had been a trooper four years. He lived at 1101 Fairmount Avenue in Fort Worth. Officer Murphy, twenty-four, had just finished trooper training. April 1 was his first day on paired duty on the highways.

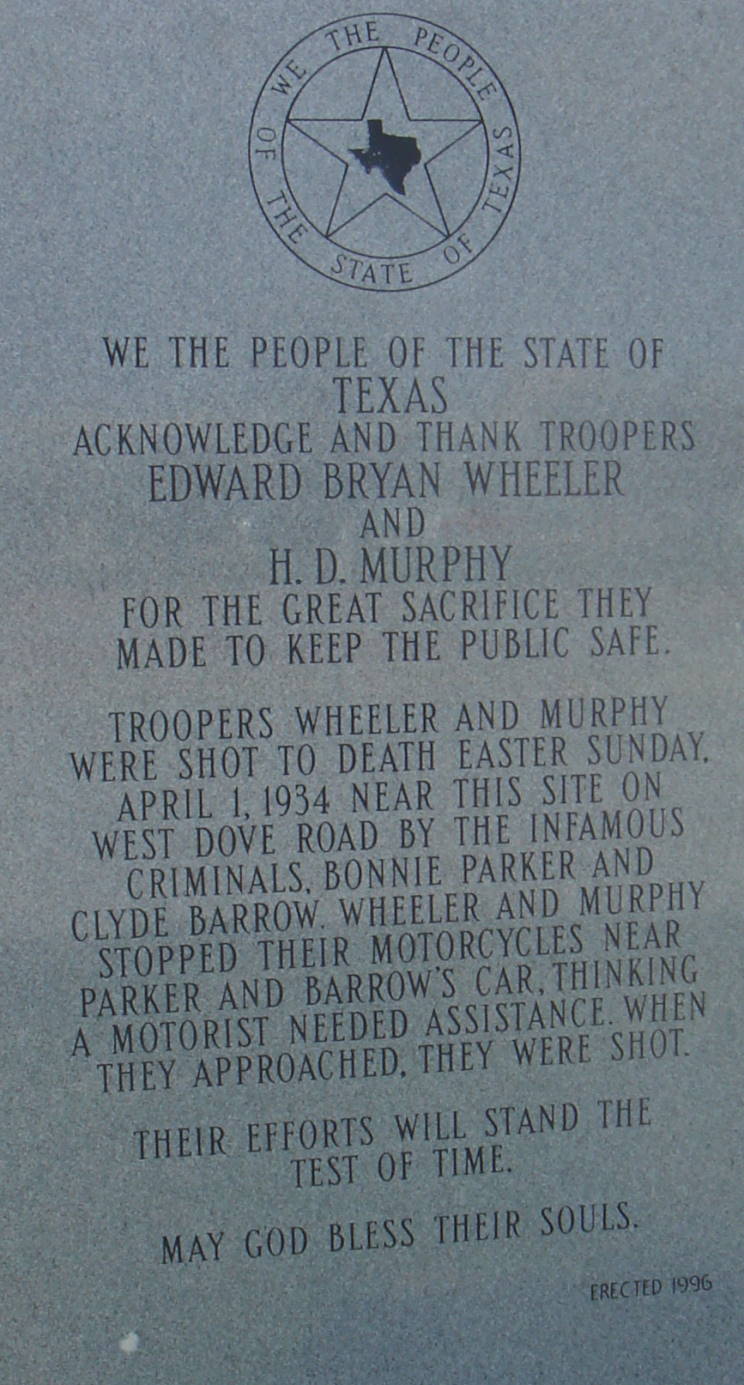

A memorial honoring the two fallen troopers stands near the scene of the crime.

A memorial honoring the two fallen troopers stands near the scene of the crime.

Officers Murphy and Wheeler became yet another chapter in the story of Bonnie and Clyde. With deputy sheriff Malcolm Davis (see Part 1), Murphy and Wheeler were among nine lawmen thought to have been killed by the Barrow gang.

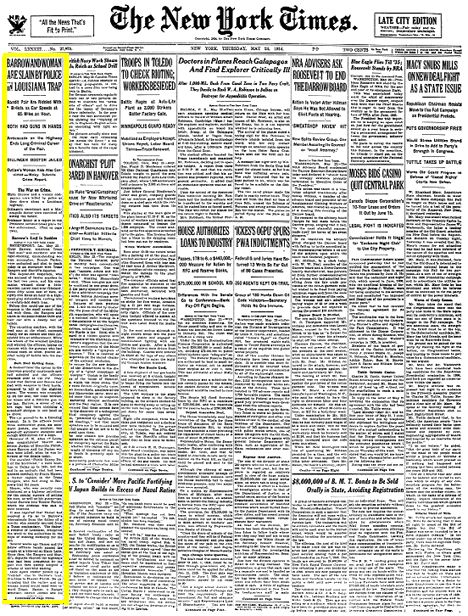

With the murders of Murphy and Wheeler public sentiment toward Bonnie and Clyde—working-class folk heroes to some—began to sour. Law enforcement increased its effort to stop the Barrow gang before another lawman or another private citizen was killed. Rewards were offered.

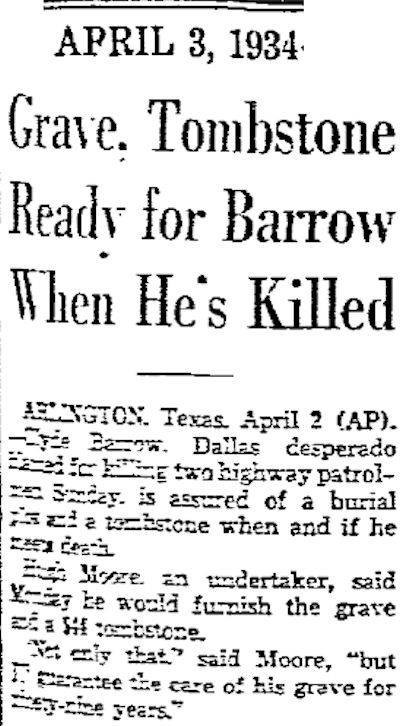

Reflecting this change in public sentiment, the day after the double murder Arlington undertaker Hugh Moore offered Clyde Barrow some free real estate.

Reflecting this change in public sentiment, the day after the double murder Arlington undertaker Hugh Moore offered Clyde Barrow some free real estate.

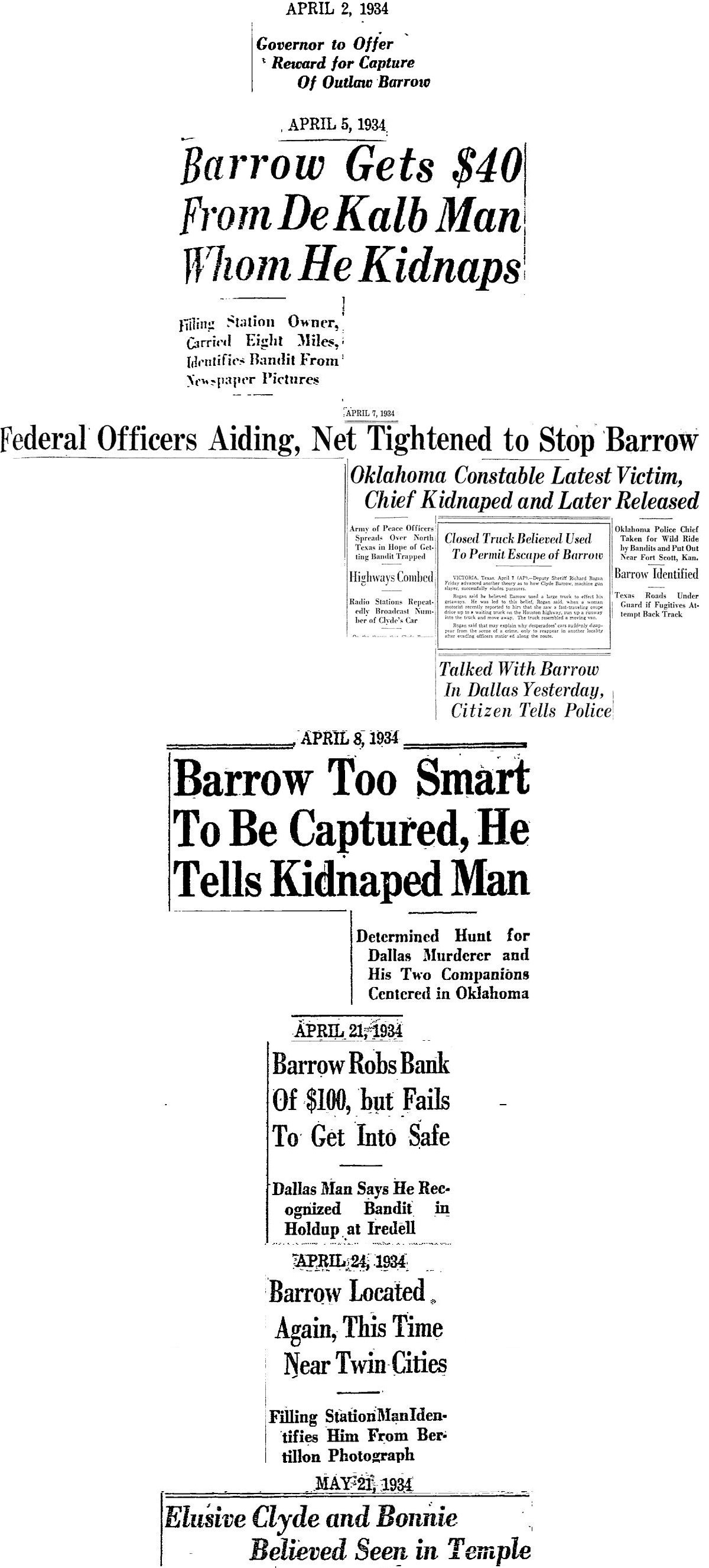

Fast-forward from April 2—past more two murders and at least two more bank robberies and numerous sightings (both real and imagined) of the gang by the public—to May 21, 1934.

Fast-forward from April 2—past more two murders and at least two more bank robberies and numerous sightings (both real and imagined) of the gang by the public—to May 21, 1934.

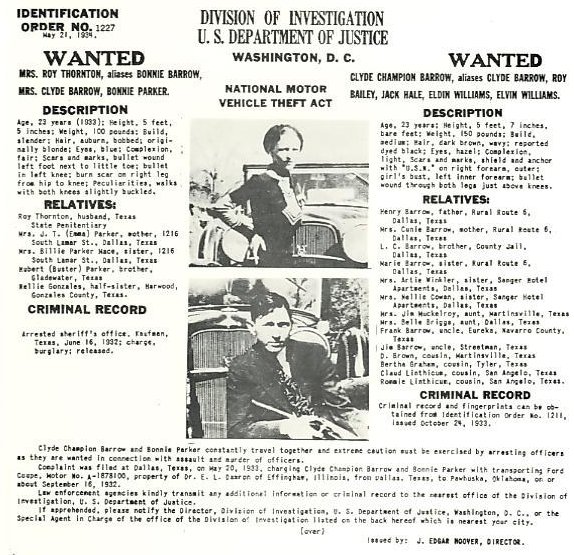

The FBI issued a wanted poster for Bonnie and Clyde. It noted that she “walks with both knees slightly buckled” from the auto accident in 1933 (see Part 1). (Photo from Federal Bureau of Investigation.)

The FBI issued a wanted poster for Bonnie and Clyde. It noted that she “walks with both knees slightly buckled” from the auto accident in 1933 (see Part 1). (Photo from Federal Bureau of Investigation.)

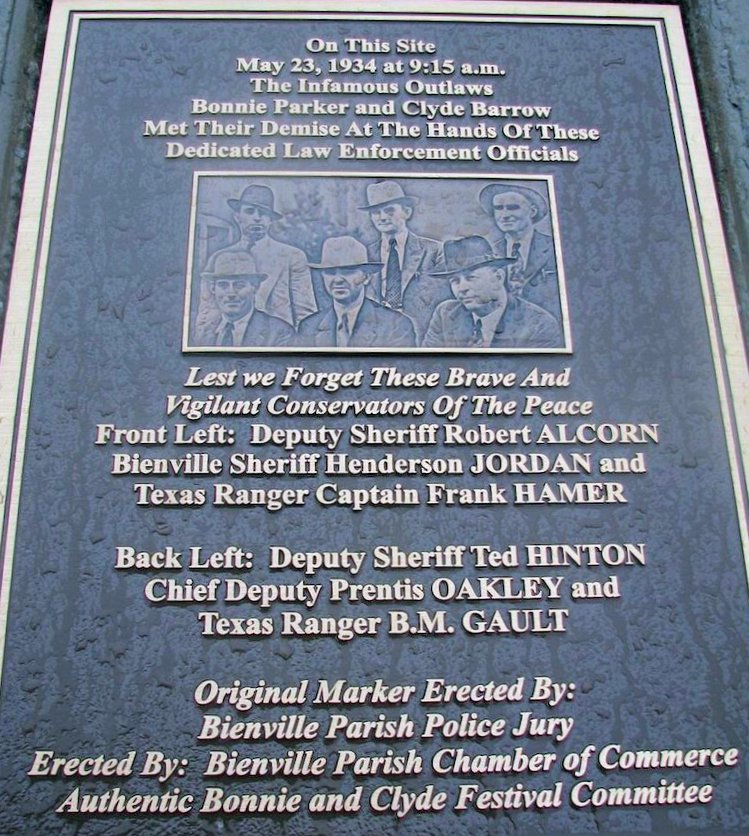

Meanwhile, because Clyde’s base of operations was west Dallas, it had made sense for ex-Texas Ranger Frank Hamer (pictured) to establish his base of operations in Dallas as he hunted for Bonnie and Clyde. Dallas County Sheriff Smoot Schmid had lent Hamer two deputies—Bob Alcorn and Ted Hinton. Hinton had known Bonnie when she was a waitress in a café near the courthouse. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

Meanwhile, because Clyde’s base of operations was west Dallas, it had made sense for ex-Texas Ranger Frank Hamer (pictured) to establish his base of operations in Dallas as he hunted for Bonnie and Clyde. Dallas County Sheriff Smoot Schmid had lent Hamer two deputies—Bob Alcorn and Ted Hinton. Hinton had known Bonnie when she was a waitress in a café near the courthouse. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

Hamer had worked his leads in the Dallas underworld—Bonnie and Clyde’s friends in low places, anyone who knew members of the Barrow gang, anyone who could get Hamer one step closer to Barrow.

Hamer had discovered that Bonnie and Clyde occasionally holed up in an abandoned farmhouse in the backwoods ten miles south of Gibsland, Louisiana not far from the home of gang member Henry Methvin’s parents, Ivan and Ava.

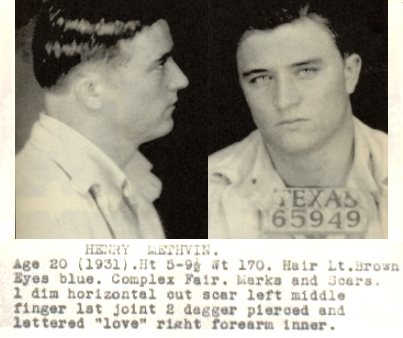

That juxtaposition had made Hamer especially interested in Henry Methvin. Methvin faced a lot of prison time, especially after escaping from Eastham prison farm and killing two state troopers. Could Hamer persuade Methvin to “flip” on Bonnie and Clyde in return for leniency?

Ivan and Ava Methvin knew Bonnie and Clyde. In fact, when Bonnie and Clyde holed up in the farmhouse hideout, Clyde claimed to be working for Ivan as a logger. With the approval of Texas Governor Miriam A. “Ma” Ferguson, Hamer had approached Henry and his parents and promised them a full parole for Henry if they would help Hamer kill or capture Bonnie and Clyde.

The Methvins agreed to help.

On May 21 Hamer and his posse built a blind of brush and vines on a hill above a long, straight stretch of Louisiana state highway 154—the road that Bonnie and Clyde traveled between Gibsland and their hideout.

Also on May 21 Henry Methvin found an excuse to slip away from Bonnie and Clyde at the hideout. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

Also on May 21 Henry Methvin found an excuse to slip away from Bonnie and Clyde at the hideout. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

Henry and Bonnie and Clyde agreed that Methvin would reunite with Bonnie and Clyde at the hideout in a few days.

Henry knew that a reunion was not to be.

On the morning of May 23 Bonnie and Clyde ate breakfast at a cafe in Gibsland and then headed back to the hideout in a stolen 1934 Ford Model 730 Deluxe V8 sedan.

Clyde was wearing a silk suit and a western-style shirt and tie. Bonnie was wearing a red dress with matching shoes and hat. She was reading a true-detective magazine.

Now Bonnie and Clyde were, as deputy sheriff Malcolm Davis and state troopers Murphy and Wheeler had been, in the wrong place at the wrong time: Louisiana state highway 154 just after 9 a.m. This time they would pay with their lives.

As the posse waited in the blind above the highway, Frank Hamer intended to fight fire with fire: Each man in the posse was armed with a Browning automatic rifle—a favored weapon of Clyde Barrow. Each man also had a twelve-gauge shotgun and two forty-five-caliber automatic pistols.

Meanwhile father Ivan Methvin had stopped his Model A logging truck in the middle of highway 154 near the posse’s blind. He removed a tire to make the truck appear disabled.

About 9:15 the posse heard the whine of a car approaching at high speed.

As Clyde drove south on highway 154, next to his left leg was a sixteen-gauge sawed-off shotgun, next to his right leg a twenty-gauge shotgun, and in his belt was a forty-five-caliber automatic pistol.

He never got a hand on them, just as state troopers Murphy and Wheeler had never gotten a hand on their pistols on Easter Sunday seven weeks earlier.

When Bonnie and Clyde recognized Ivan Methvin standing beside his truck Clyde slowed the car.

That was Ivan Methvin’s cue. He ran into the woods, out of harm’sway.

And that was Hamer’s cue.

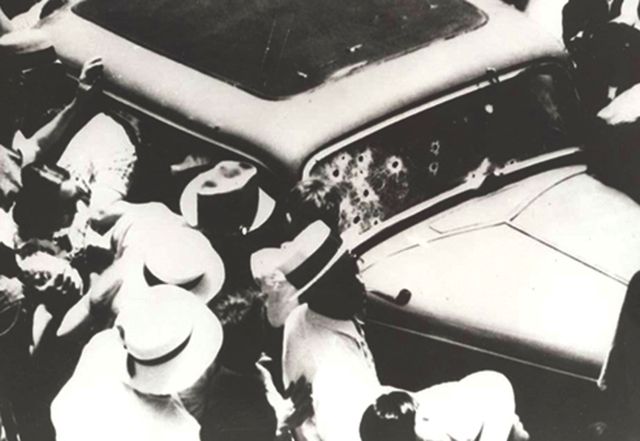

In the first three seconds the lawmen fired 120 steel-jacketed .30-06 rounds from their Brownings. In those three seconds the car became a four-door coffin. Bonnie screamed as the first two shots hit Clyde in the head, killing him instantly.

With Clyde dead behind the wheel, the car began to roll down the hill. The posse members continued to fire, emptying first their Browning automatic rifles, then their shotguns, then their handguns. On and on the six men fired at the two inert bodies, as if venting two years of frustration by the American justice system as Bonnie and Clyde had robbed, killed, eluded manhunts, and survived gunfights only to rob and kill again.

Not this time.

According to statements by posse members Hinton and Bob Alcorn:

“Each of us six officers had a shotgun and an automatic rifle and pistols. We opened fire with the automatic rifles. They were emptied before the car got even with us. Then we used shotguns . . . There was smoke coming from the car, and it looked like it was on fire. After shooting the shotguns, we emptied the pistols at the car, which had passed us and ran into a ditch about 50 yards on down the road. It almost turned over. We kept shooting at the car even after it stopped. We weren’t taking any chances.”

Photo from Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Photo from Federal Bureau of Investigation.

The posse members, temporarily deafened by their bombardment, inspected the perforated Ford. In the front seat two bloody rag dolls slumped forward. Clyde had been hit at least twenty-five times, Bonnie at least twenty-eight. The South’s most notorious crime couple had been killed a dozen times over. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

The posse members, temporarily deafened by their bombardment, inspected the perforated Ford. In the front seat two bloody rag dolls slumped forward. Clyde had been hit at least twenty-five times, Bonnie at least twenty-eight. The South’s most notorious crime couple had been killed a dozen times over. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

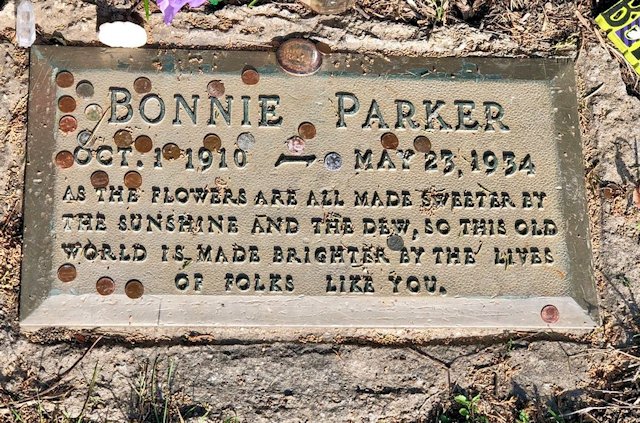

Bonnie Elizabeth Parker was twenty-three. Clyde Chestnut Barrow was twenty-five.

Ted Hinton, who had known Bonnie in what now seemed like another life, opened the door on the passenger side and lifted her, all one hundred pounds, hoping she might still be alive. After a moment he placed her back on the front seat.

The posse found the Barrow car to be a rolling armory: stolen automatic rifles, sawed-off semiautomatic shotguns, handguns, and several thousand rounds of ammunition (including one hundred twenty-round Browning automatic rifle magazines), along with fifteen sets of stolen license plates. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

The posse found the Barrow car to be a rolling armory: stolen automatic rifles, sawed-off semiautomatic shotguns, handguns, and several thousand rounds of ammunition (including one hundred twenty-round Browning automatic rifle magazines), along with fifteen sets of stolen license plates. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

Also inside the car was this visual non sequitur: Among the high-powered armament was Clyde’s saxophone. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

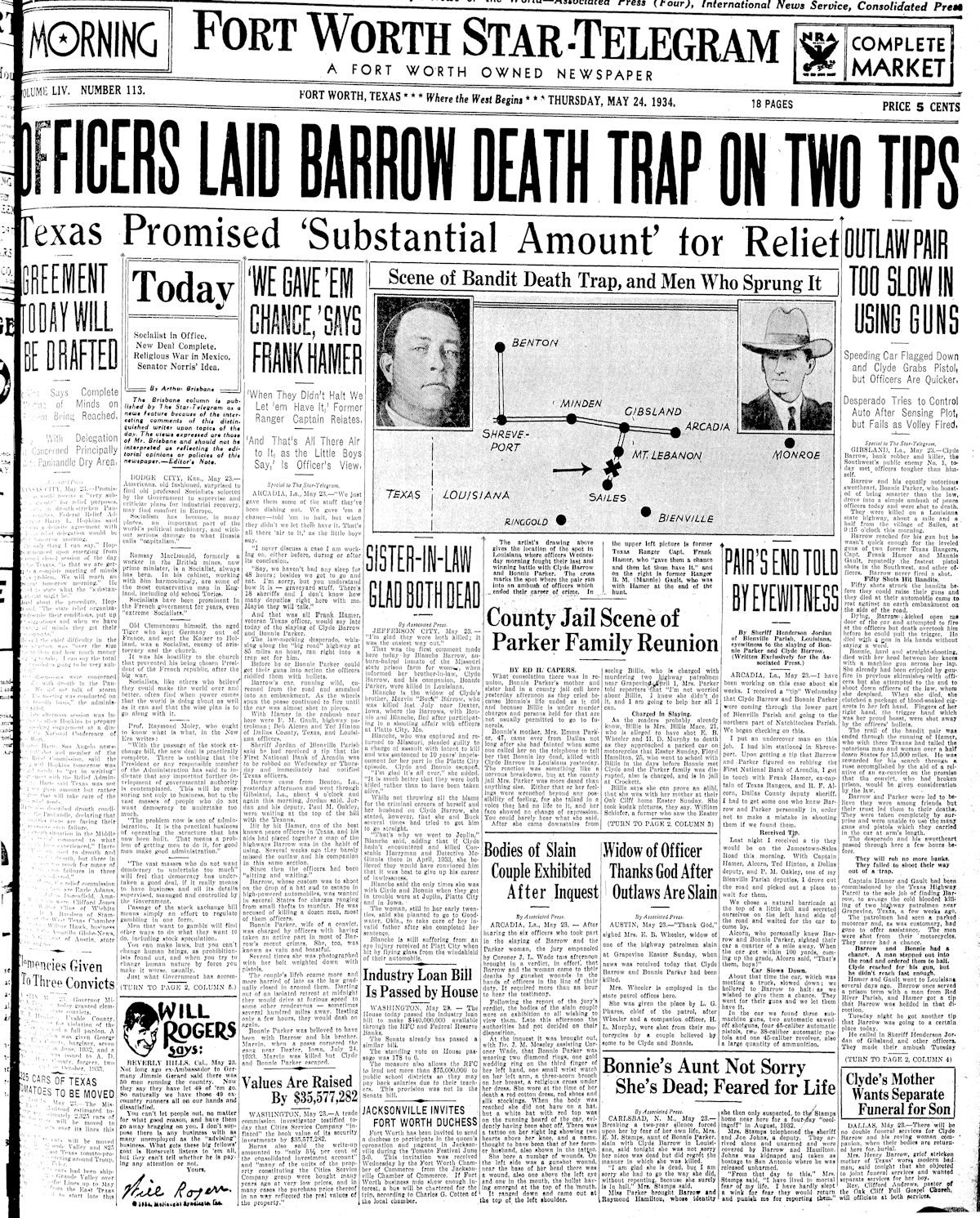

The ambush made the front page of the New York Times.

The ambush made the front page of the New York Times.

After the ambush the morbid public circus began. In the remote backwoods of Louisiana a crowd quickly gathered at the ambush scene. Two members of the posse, left to guard the corpses, lost control of the jostling, curious throng. One woman cut off locks of Parker’s hair and pieces of her dress, which were sold as souvenirs. One man tried to cut off Barrow’s trigger finger.

Arriving at the scene, the coroner saw the following: “. . . nearly everyone had begun collecting souvenirs such as shell casings, slivers of glass from the shattered car windows, and bloody pieces of clothing from the garments of Bonnie and Clyde. One eager man had opened his pocket knife, and was reaching into the car to cut off Clyde’s left ear.”

The shot-up Ford, with the bodies still inside, was towed to Arcadia, Louisiana and put on public view at a furniture store that doubled as a funeral parlor.

At the coroner’s inquest someone stole Clyde’s diamond stickpin.

Undertaker C. F. “Boots” Bailey had difficulty embalming the bodies because of all the bullet holes. Assisting Bailey was a man named “Dillard Darby.” The Barrow gang had kidnapped Darby a year earlier after the gang stole his car and he tried to retrieve it and was taken hostage by the gang. Bonnie had been morbidly amused to learn that Darby was an undertaker. E. R. Milner in The Lives and Times of Bonnie & Clyde writes that Bonnie said to Darby: “When the law catches us, you can fix us up.”

And so he did.

In Dallas a man offered to pay Clyde’s family $50,000 ($900,000 today) for Clyde’s body, which the man wanted to mummify and exhibit in a traveling tent show.

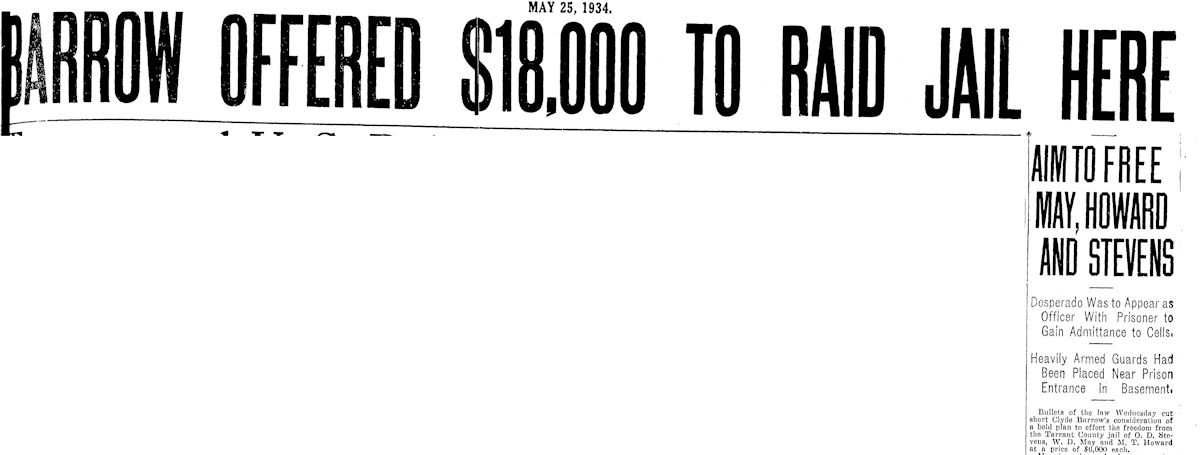

The death of Bonnie and Clyde must have been disheartening to O. D. Stevens of Handley. After Clyde was killed U.S. Marshal J. R. “Red” Wright told a newspaper that authorities had recently learned that Clyde had agreed to break Stevens and his associates W. D. May and M. T. Howard out of the Tarrant County jail, where they were being held after a mail train robbery and the murder of three gang members. Stevens, impressed by Clyde’s liberation of Raymond Hamilton from Eastham prison farm, had agreed to pay Clyde $18,000 ($340,000 today).

The death of Bonnie and Clyde must have been disheartening to O. D. Stevens of Handley. After Clyde was killed U.S. Marshal J. R. “Red” Wright told a newspaper that authorities had recently learned that Clyde had agreed to break Stevens and his associates W. D. May and M. T. Howard out of the Tarrant County jail, where they were being held after a mail train robbery and the murder of three gang members. Stevens, impressed by Clyde’s liberation of Raymond Hamilton from Eastham prison farm, had agreed to pay Clyde $18,000 ($340,000 today).

The sharecropper’s son and the county spelling bee champion, who had inflicted so much upon so many in a desperate attempt to escape from west Dallas, were returned to west Dallas.

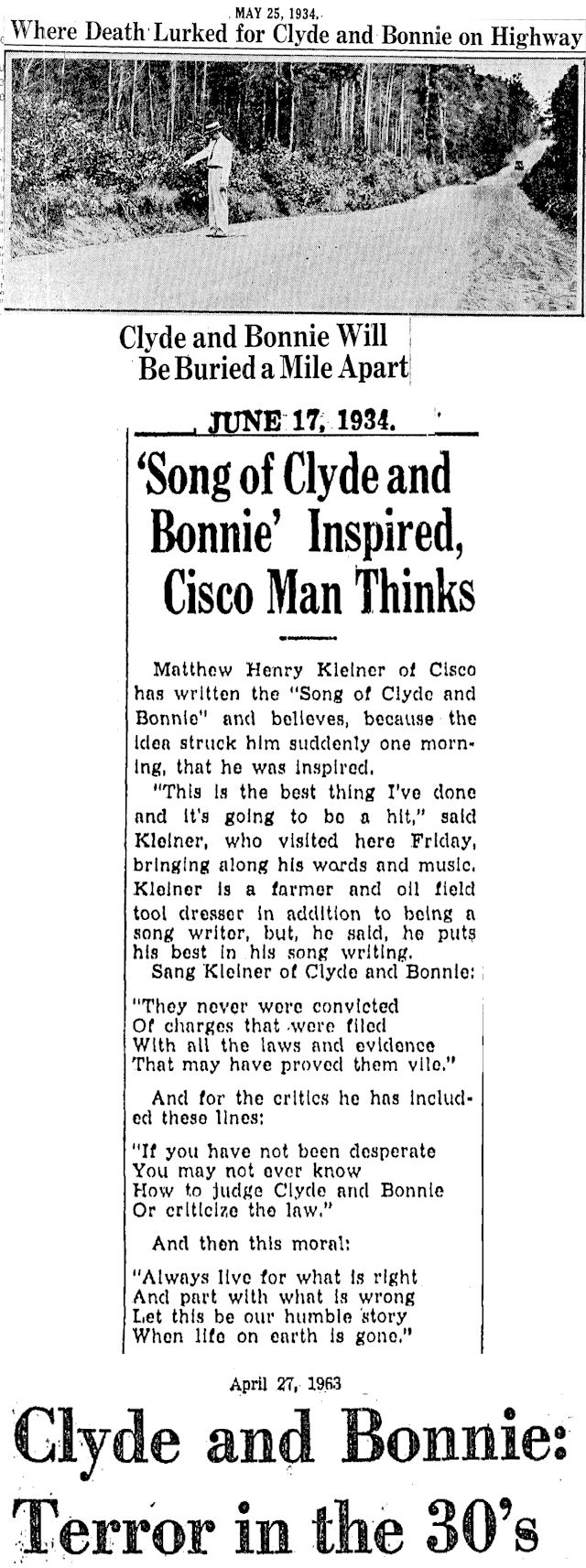

Bonnie was buried in Fishtrap Cemetery, Clyde in Western Heights Cemetery.

Even though both funerals were private, thousands of people milled about the funeral homes and cemeteries. One entrepreneur set up an ice cream stand nearby and did good business.

Clyde’s funeral was held at Sparkman-Holden-Brand Funeral Home (once the mansion of Colonel A. H. Belo) on Ross Avenue.

During Barrow’s private graveside service an airplane flew over low and dropped a spray of flowers. The flowers were from gambler and police character Benny Binion.

Bonnie’s family received sympathy cards allegedly sent by Pretty Boy Floyd and John Dillinger. The largest floral tribute was sent by a group of Dallas newsboys; the deaths of Bonnie and Clyde had sold a half-million newspapers in Dallas alone.

Bonnie, dressed in a blue silk negligee, was laid out in a silver casket. Her permanent wave partly concealed her head wounds.

Bonnie’s sister, Mrs. Billie Parker Mace, attended Bonnie’s funeral in the custody of the Tarrant County sheriff and four deputies. Mrs. Mace was being held for questioning in the Dove Road murders on Easter Sunday.

And now that Bonnie and Clyde were dead and buried, the next stage for them was immortality.

After all, they had what it takes: They were reckless, they were in love, and they died young.

Bonnie and Clyde’s time in the headlines had been little more than two years. And eighty years ago at that. But legends don’t die with the passage of time. Indeed, they feed on time.

The process began quickly. By the weekend Bonnie and Clyde’s death was shown in newsreel footage by at least two Dallas theaters.

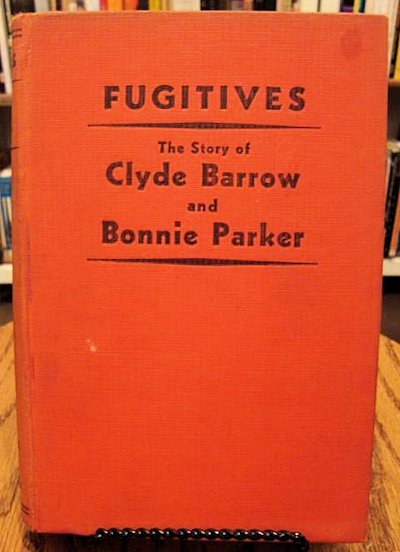

Then came the books. Dozens of them. Among the first to be published after the death of Bonnie and Clyde was Fugitives: The Story of Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker (1934) as told by Bonnie’s mother Emma and Clyde’s sister Nell. Clyde’s sister Marie told the story in The Family Story of Bonnie and Clyde. Buck Barrow’s widow Blanche told the story in My Life with Bonnie and Clyde. Gang member Ralph Fults told the story in Running With Bonnie and Clyde: The Ten Fast Years of Ralph Fults.

Then came the books. Dozens of them. Among the first to be published after the death of Bonnie and Clyde was Fugitives: The Story of Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker (1934) as told by Bonnie’s mother Emma and Clyde’s sister Nell. Clyde’s sister Marie told the story in The Family Story of Bonnie and Clyde. Buck Barrow’s widow Blanche told the story in My Life with Bonnie and Clyde. Gang member Ralph Fults told the story in Running With Bonnie and Clyde: The Ten Fast Years of Ralph Fults.

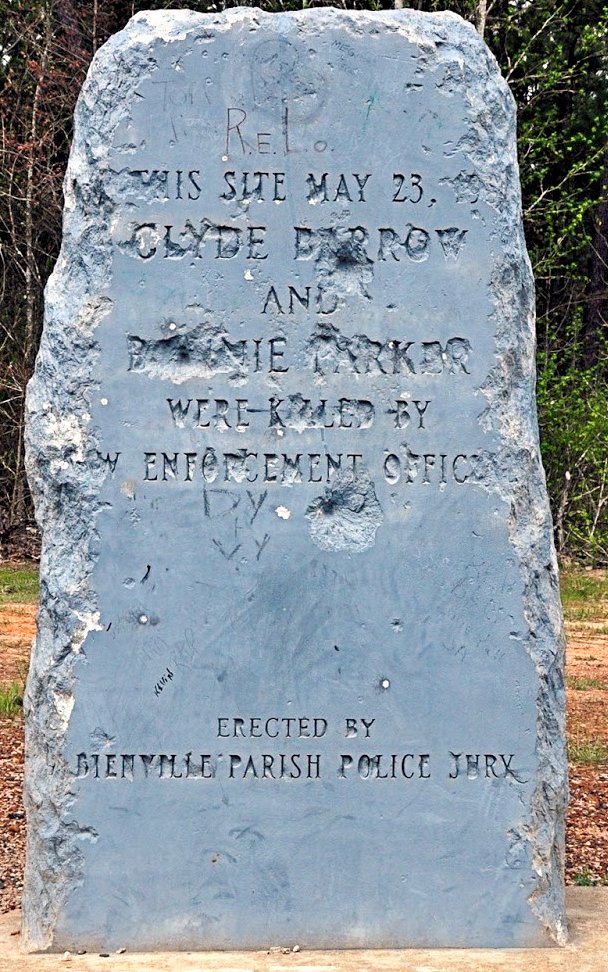

Today books (and blog posts) are still being written, documentaries made, monuments dedicated, details of their life debated.

Today books (and blog posts) are still being written, documentaries made, monuments dedicated, details of their life debated.

The houses they lived in, the schools they attended, the scenes of their crimes are stops on Bonnie and Clyde guided tours.

Their personal effects, from eyeglasses to clothing, are highly prized in private collections and museums.

The “death car,” after being displayed around the country for years (including at the Great American Road Rally in Arlington in 1988), is now in a casino in Nevada.

Their graves are still visited by people who never knew them. People leave flowers, coins, and other mementoes. Some give, others take: John Neal Phillips, author of Running With Bonnie and Clyde: The Ten Fast Years of Ralph Fults, said of Barrow’s tombstone: “Someone used to steal it every Texas-OU weekend. One time the police recovered it from the home of a prominent businessman who was using it as a coffee table to entertain his weekend guests.”

Their graves are still visited by people who never knew them. People leave flowers, coins, and other mementoes. Some give, others take: John Neal Phillips, author of Running With Bonnie and Clyde: The Ten Fast Years of Ralph Fults, said of Barrow’s tombstone: “Someone used to steal it every Texas-OU weekend. One time the police recovered it from the home of a prominent businessman who was using it as a coffee table to entertain his weekend guests.”

Today the tombstones of both Bonnie and Clyde are set in concrete to discourage theft.

And, of course, as immortals, Bonnie and Clyde lost their need for last names. Think Elvis, Capone, Cher. In the beginning Bonnie and Clyde were referred to as “the Barrow gang” and “Clyde Barrow and his woman companion” and then “Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker.”

Gradually they became . . . “Clyde and Bonnie.” Huh? Today first billing for Clyde sounds strange to our ears, especially after the 1967 movie.

Gradually they became . . . “Clyde and Bonnie.” Huh? Today first billing for Clyde sounds strange to our ears, especially after the 1967 movie.

As Bonnie Elizabeth Parker Thornton, county spelling bee champ, sat beside Clyde Barrow. sharecropper’s son, while their various stolen V8 Fords careened down all those two-lane roads from all those heists to all those hideouts, she had seemed to foresee what they someday would meet as they topped the next rise in the road. The final stanza of her poem “The Story of Bonnie and Clyde”:

Some day they’ll go down together;

And they’ll bury them side by side;

To few it’ll be grief

To the law a relief

But it’s death for Bonnie and Clyde.

several years ago I was down that way over to gibsland ,la.boots henton was raising money to put up new site markers.sad to see them all shoot up.good work mike.

Thanks, Earl. Markers in the middle of nowhere are easy targets, I guess.