About 9:25 on the night of January 7, 1908, the Fort Worth Telegram reported the next day, passengers on a streetcar crossing the Jennings Avenue viaduct saw a “faint blaze” under the eave of the west end of the Texas & Pacific freight depot about five hundred feet east of the viaduct.

Passengers, including County Commissioner Duff Purvis, said they watched as the blaze traveled along a “narrow thread, apparently a light wire.”

Another passenger, attorney R. H. Buck, said, “I could have extinguished the blaze with a single bucket of water and really started to get off the car and go to the scene, but the blaze was apparently so insignificant that I was sure the watchman would be able to handle it without assistance.”

At about the same time, the Fort Worth Record reported the next day, men working at the depot heard three explosions at three-minute intervals in the depot’s warehouse section. Almost a half-mile away at the Metropolitan Hotel at Main and 9th streets, Dr. A. W. Miller said he, too, heard three explosions.

T&P employee J. S. Wood said he was in the depot within thirty feet of the point of the first explosion. He said the explosion blew out windows of the depot and blew off a portion of the roof.

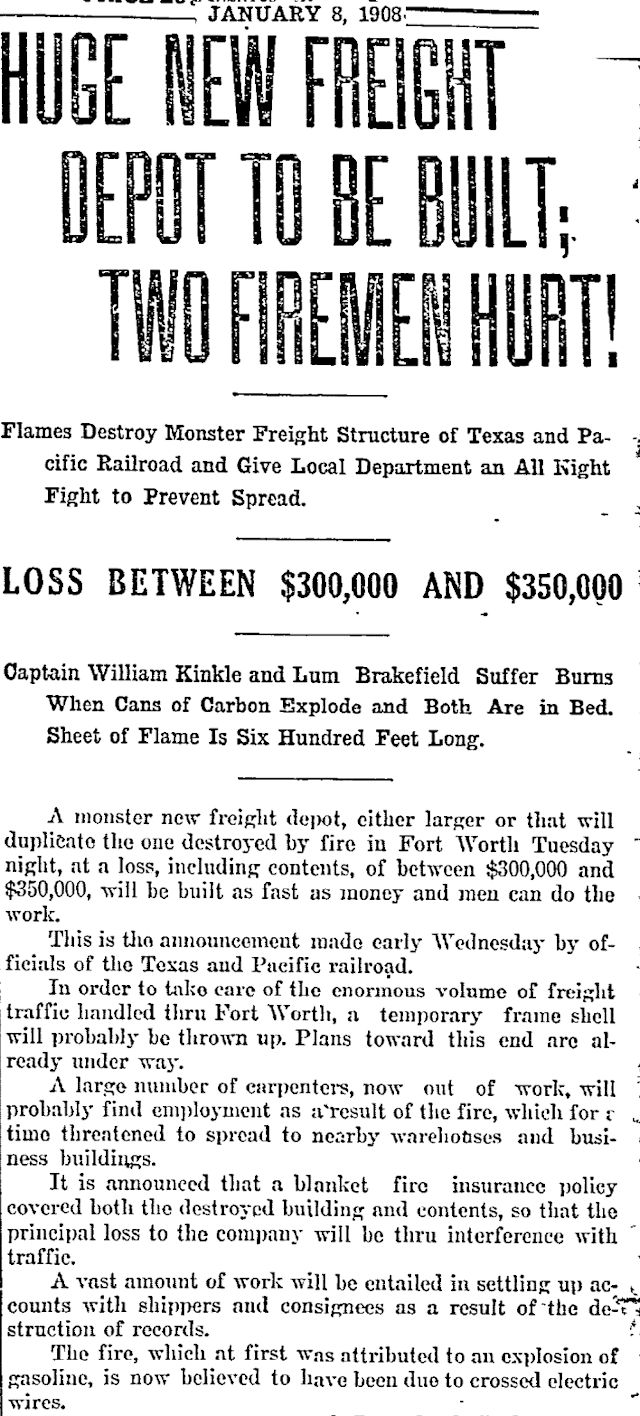

The front page of the Telegram January 8.

The front page of the Telegram January 8.

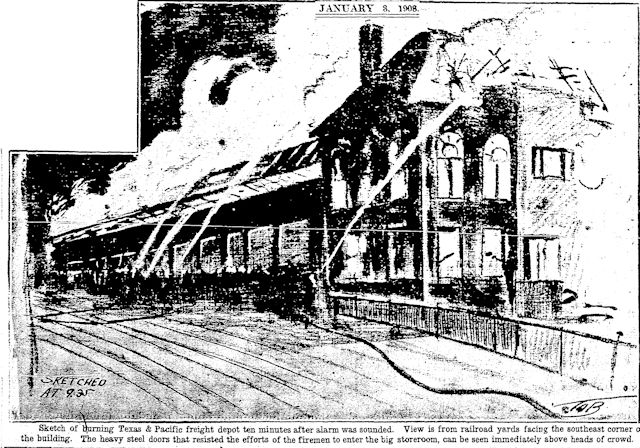

The Fort Worth Record printed the story and a sketch on an inside page. The T&P depot also handled freight for the International & Great Northern and Katy railroads.

The Fort Worth Record printed the story and a sketch on an inside page. The T&P depot also handled freight for the International & Great Northern and Katy railroads.

The T&P freight depot, built in 1902, was a huge structure, stretching six hundred feet along Lancaster Avenue with 330,000 cubic feet of storage space.

The T&P freight depot, built in 1902, was a huge structure, stretching six hundred feet along Lancaster Avenue with 330,000 cubic feet of storage space.

This Charles Swartz photo of the freight depot’s office building was taken in 1905 when President Roosevelt spoke in the public square between the freight office and the 1899 T&P passenger station. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Librar

This Charles Swartz photo of the freight depot’s office building was taken in 1905 when President Roosevelt spoke in the public square between the freight office and the 1899 T&P passenger station. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Librar

This undated photo shows the freight depot from the intersection of Main and Lancaster streets. Behind the streetcar can be seen the top of the Al Hayne memorial. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

The wind was blowing briskly from the west on the night of January 7, 1908. Vents at the west and east ends of the depot allowed the wind to blow into the warehouse section and create a draft that spread the fire so quickly that the depot was engulfed in five minutes.

No one was working in the warehouse section that night. Thirty-five clerks were working in the brick office building on the east end. When the fire was discovered, one clerk ran to the nearest fire alarm on Main Street. Other clerks tried to fight the fire with water buckets and hand extinguishers but were soon outmatched and fled the building.

One clerk, twenty-five-year-old Walter Shedd, fled the burning office building with his colleagues but then stopped and ran back into the fire and smoke, risking his life to rescue . . . his typewriter.

Meanwhile twenty-five loaded freight cars were standing on a track alongside the depot when the fire broke out. Daniel Tubbs and other engineers in the train yard quickly began using switch engines to move the cars to safety.

During the age of steam downtown Fort Worth could be a mighty loud place, what with locomotives coming and going from several train yards day and night. There were few sounds louder than a locomotive engine.

One of those sounds was a locomotive whistle.

As the engineers worked to move the freight cars away from the fire, they began to blow their engine whistles and kept up the cacophony to draw attention to the emergency.

Firemen at the central fire station ten blocks away at Throckmorton and Monroe streets heard the engine whistles before they received the fire alarm and knew there must be a fire in one of Fort Worth’s several train yards. The fire horses were in harness, and the firemen were on their wagons before the first alarm was received.

Six fire companies responded. Fifteen streams of water were quickly trained on the fire.

But it was too little too late. The sides and doors of the depot’s warehouse section were corrugated steel. Firemen were hampered because the doors could not be opened so that firemen could access the interior of the warehouse section. Firemen had to stand outside the building and aim their hoses over the walls to get the water onto the fire through the collapsed roof.

So intense was the heat of the fire that a telephone pole two blocks away burned. As poles nearer the depot burned, people had to avoid falling telephone, electric, and telegraph wires.

Streetcars were diverted from their routes because fire hoses were laid across the tracks.

After firemen realized that the depot and its contents could not be saved, they turned their attention to preventing the fire from spreading to adjacent businesses. Only one commercial building, housing a feedstore, received minor damage.

The glare of the fire could be seen for miles. The Record wrote that the burning depot was quickly surrounded by “a wall of humanity”—perhaps twenty thousand people. Onlookers filled the train yard and the surrounding streets. People perched on the tops of boxcars in the train yard, lined the Jennings Avenue viaduct, even hopped onto freight trains moving through the train yard and watched from the top of cars.

A dozen policemen worked to keep the crowd out of the way of firemen.

The Record noted the number of women watching, dressed in “beautiful gowns that but a few minutes before graced the ballroom, the opera box or the parlor.”

Boys eagerly volunteered to carry hoses for the firemen. Now and then, the Record wrote, a fireman would aim his hose at a cluster of boys and ricochet a stream of water off the street to move them back out of harm’s way.

The depot fire burned itself out after two hours.

Only two injuries were reported: Two firemen were burned when cans of carbon in the warehouse exploded.

The Record wrote that “there was nothing left of the once splendid structure but a smoldering pile of brick and iron ruins.”

The depot was located about five hundred feet from where another “once splendid structure”—the Spring Palace—had burned just as quickly in 1890.

The Record said the loss of building and contents was $250,000 ($7 million today), called the fire “one of the costliest in the history of Fort Worth.” The Telegram put the loss even higher.

So, what caused the fire—electrical wiring (as the Telegram reported) or explosions (as the Record reported)? T&P freight agent A. W. Montague said that, per railroad regulations, no gasoline, gunpowder, or other explosives were stored in the depot. But T&P officials also dismissed electricity as the cause of the fire, saying that power to the building was cut off at 6:30 each evening. The depot electricity was supplied by a generator in the basement of the 1899 passenger depot.

As of January 13 the Telegram reported that the cause remained “mysterious.”

T&P responded to the catastrophe quickly. The Record reported that Page Harris, T&P division superintendent, was on his way to Fort Worth from Marshall before the fire burned itself out. Texas & Pacific faced two immediate challenges: 1. keep freight moving by providing temporary storage for freight and temporary office space for freight clerks and 2. replace the depot.

Freight operation returned to near normal within two days. An army of carpenters threw up temporary freight shelters. Some freight was simply loaded into parked freight cars in the train yard, the cars acting as mini-freight depots.

On the morning after the fire T&P announced that it would begin work “at once” on clearing the ruins and rebuilding the depot on the site, using the concrete foundation, which was not damaged.

On January 31 the Telegram reported that work on the new depot was “progressing rapidly,” even though there had been a delay in a shipment of bricks from Thurber.

On January 31 the Telegram reported that work on the new depot was “progressing rapidly,” even though there had been a delay in a shipment of bricks from Thurber.

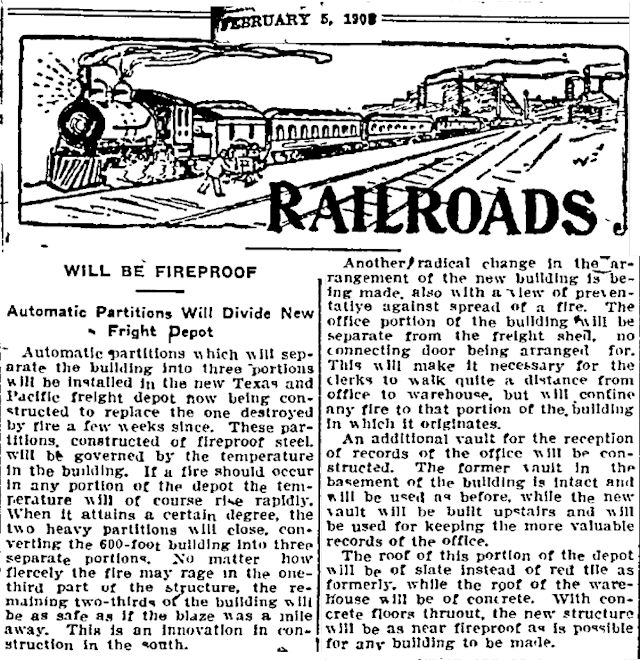

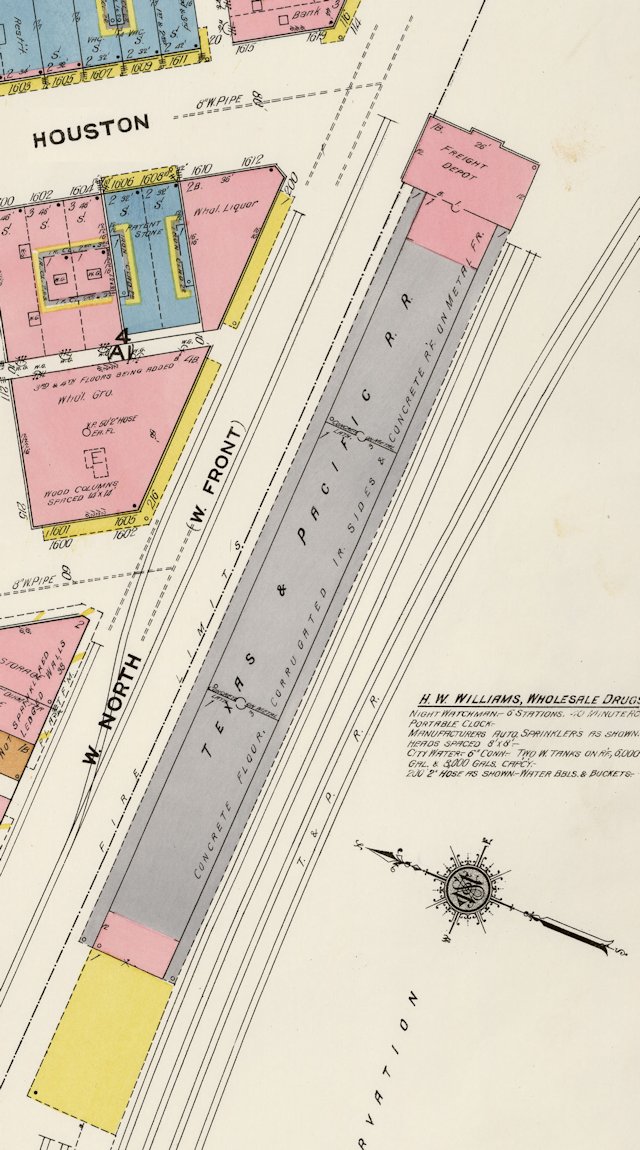

Texas & Pacific, seeking to learn from the past, incorporated features to make the new depot “as near fireproof as is possible.” Two partitions of fireproof steel would divide the warehouse section into three areas. The partitions would automatically close when triggered by high temperatures, confining a fire to one of the three areas. Also the office building would not be attached to the warehouse section. The office building would have an additional vault. The roof of the office building would be of slate, the roof of the warehouse section of concrete. Floors throughout would be of concrete.

Texas & Pacific, seeking to learn from the past, incorporated features to make the new depot “as near fireproof as is possible.” Two partitions of fireproof steel would divide the warehouse section into three areas. The partitions would automatically close when triggered by high temperatures, confining a fire to one of the three areas. Also the office building would not be attached to the warehouse section. The office building would have an additional vault. The roof of the office building would be of slate, the roof of the warehouse section of concrete. Floors throughout would be of concrete.

(The Katy railroad would open its own fireproof freight depot on East Vickery Boulevard in January 1909. That depot would survive the South Side fire in September.)

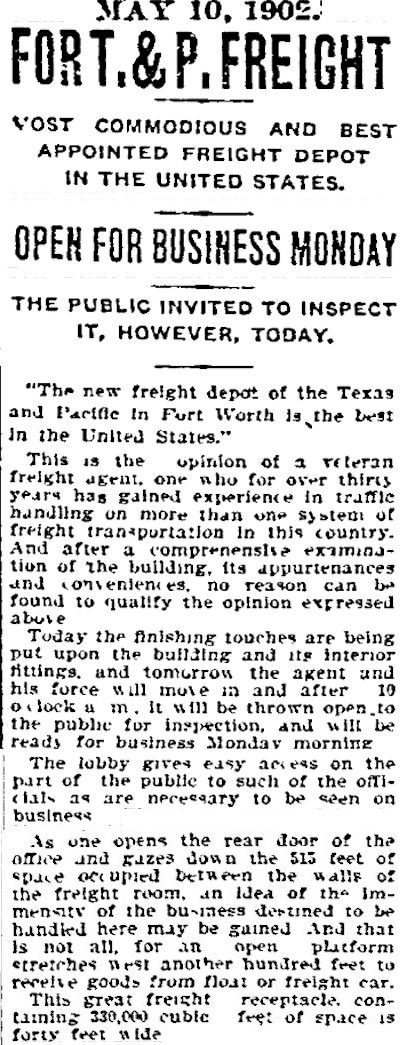

In less than four months T&P’s replacement freight depot was completed.

In less than four months T&P’s replacement freight depot was completed.

The 1910 Sanborn map shows the office building and the warehouse section with its two automatic partitions. (Front Street is today’s Lancaster Avenue.)

The 1910 Sanborn map shows the office building and the warehouse section with its two automatic partitions. (Front Street is today’s Lancaster Avenue.)

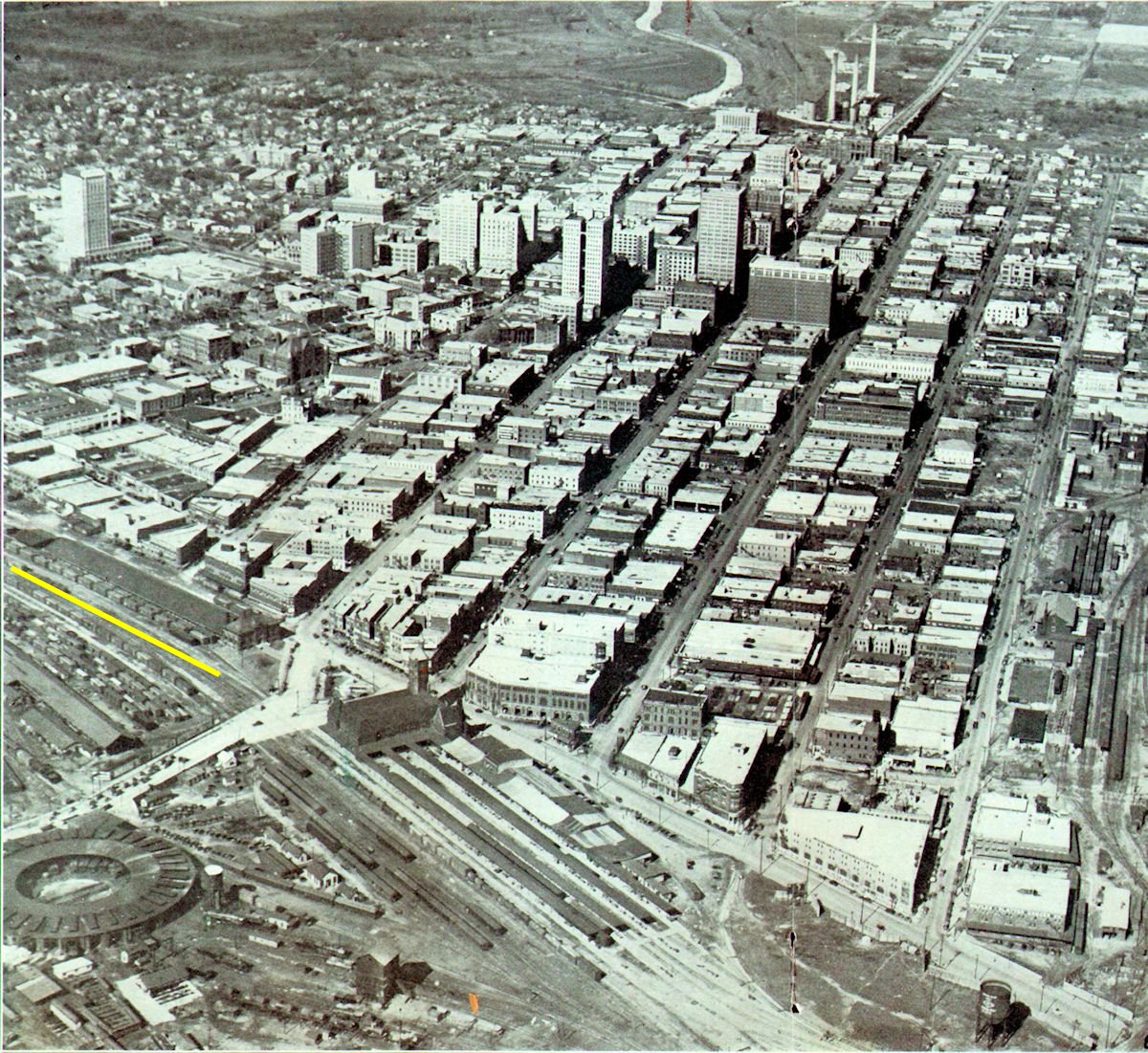

The 1908 depot appears on the left side of this 1928 aerial photo.

The 1908 depot appears on the left side of this 1928 aerial photo.

This grainy closeup shows that the 1908 depot was very similar to the 1902 depot.

This grainy closeup shows that the 1908 depot was very similar to the 1902 depot.

This 1932 photo looking west along the railroad tracks shows two pairs of old and new: On the right are the 1899 passenger depot and the 1908 freight depot. On the left are the 1931 passenger and freight depots. (Photo by J. W. Barriger III from his collection in the National Railroad Library.)

This 1932 photo looking west along the railroad tracks shows two pairs of old and new: On the right are the 1899 passenger depot and the 1908 freight depot. On the left are the 1931 passenger and freight depots. (Photo by J. W. Barriger III from his collection in the National Railroad Library.)

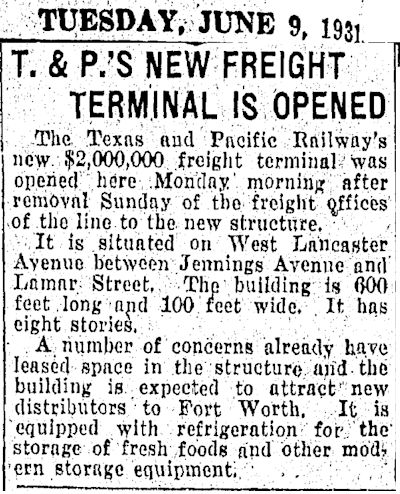

In 1931 T&P replaced the 1908 depot with a much bigger depot: six hundred feet long, one hundred feet wide, and eight stories high.

In 1931 T&P replaced the 1908 depot with a much bigger depot: six hundred feet long, one hundred feet wide, and eight stories high.

The 1931 freight depot was part of T&P’s transformation of the south end of downtown: new passenger depot, new freight depot, and vehicular underpasses on Main, Jennings, and Henderson streets.

The 1931 freight depot was part of T&P’s transformation of the south end of downtown: new passenger depot, new freight depot, and vehicular underpasses on Main, Jennings, and Henderson streets.

Footnote: Seven of Fort Worth’s early fires (four of them on railroad property) occurred in the area between Lancaster Avenue and Hattie Street south of downtown: Spring Palace (1890), 1882 T&P passenger depot (1896), 1899 T&P passenger depot (1904), Fifth Ward school and Missouri Avenue Methodist Church (1904), T&P freight depot (1908), South Side (1909), Fort Worth High School (1910).

(Thanks to historian Dr. Richard Selcer for the tip.)