Most people run from fire. Only a few run to fire. Some of those who run to fire are paid to do so: professional firefighters. But some who run to fire harbor no expectation of payment.

They are volunteer firefighters, and Fort Worth has long benefited from volunteer firefighters both organized and impromptu.

In fact, when the city incorporated in 1873, and B. B. Paddock organized Fort Worth’s first firefighting unit, it was made up of sixty volunteers. Not until 1893 did Fort Worth start paying its firefighters.

In fact, retired Fort Worth police sergeant and historian Kevin Foster says Fort Worth’s professional firefighters relied on volunteer firefighters well into the twentieth century.

In fact, retired Fort Worth police sergeant and historian Kevin Foster says Fort Worth’s professional firefighters relied on volunteer firefighters well into the twentieth century.

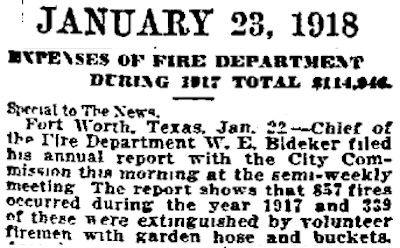

For example, in 1918 Fire Chief William E. Bideker in his annual report reported that in 1917 volunteer firefighters had extinguished 339 fires equipped with just buckets and garden hoses.

By the time Bideker issued that report in 1918, one such volunteer firefighter—of the impromptu type—had been dead six years.

And Bideker had led the attempt to save his life.

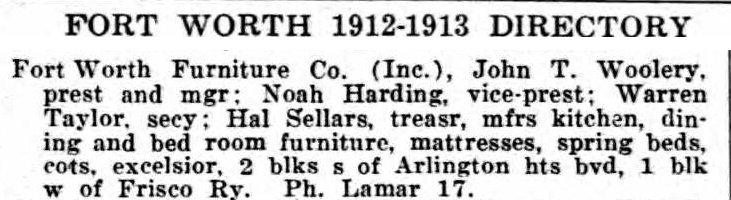

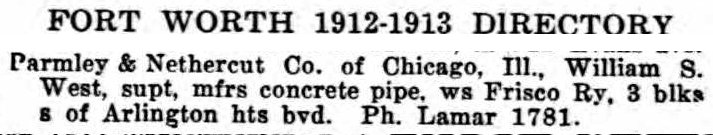

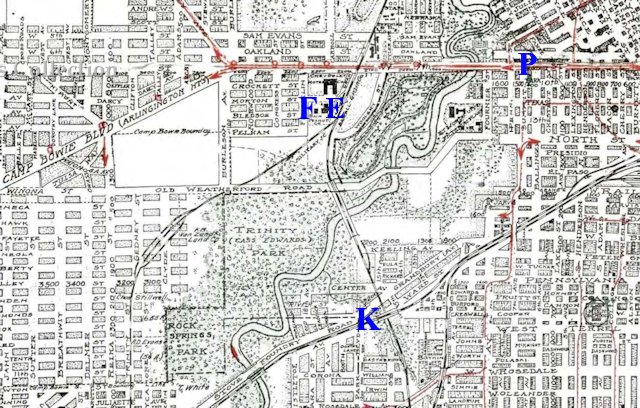

At 10 o’clock on the night of March 5, 1912 the night watchman of the Fort Worth Furniture Company factory, located two blocks south of West 7th Street and one block west of the Frisco railroad tracks, discovered that one of the factory’s buildings was on fire. He began blowing the factory’s steam whistle as an alarm. At the adjacent Parmley & Nethercut concrete pipe company, night watchman William B. Moser heard the whistle, saw the smoke, and turned in the fire alarm.

At 10 o’clock on the night of March 5, 1912 the night watchman of the Fort Worth Furniture Company factory, located two blocks south of West 7th Street and one block west of the Frisco railroad tracks, discovered that one of the factory’s buildings was on fire. He began blowing the factory’s steam whistle as an alarm. At the adjacent Parmley & Nethercut concrete pipe company, night watchman William B. Moser heard the whistle, saw the smoke, and turned in the fire alarm.

In less than a minute, the Fort Worth Record reported the next day, the “big auto engine” of Company 2 at the central fire station at Throckmorton and Monroe streets downtown was on its way to the fire (the fire department had only recently converted from horse-drawn to gasoline-powered vehicles).

As the professional firefighters were responding, so were the volunteers.

About a mile south of the furniture factory on Stove Foundry Road (today West Vickery Boulevard) Frank Peter Keniff, an employee of Parmley and Nethercut, saw the flames and smoke rising above the trees of Trinity Park to the north.

Suspecting that his place of employment or one very near it was on fire, he bid his wife of eight months goodbye and ran to the fire. Accompanying Keniff was Nathan Moser, who also lived on Stove Foundry Road and was the son of the night watchman of Parmley & Nethercut.

To reach the fire Keniff and Nathan Moser had to across the Trinity River. They probably crossed on the Frisco railroad bridge near today’s Forest Park Boulevard and followed the track north. The Frisco track passed within a block of the burning factory.

After Keniff and Moser reached the factory Keniff used a hammer to break through the fence around the factory. He then organized other volunteers into a bucket brigade. Some of those volunteers may have been employees of the furniture factory who lived in cottages around the factory.

As the bucket brigade of volunteers was fighting the fire, Company B of the Fort Worth fire department arrived. The fire department had responded to the alarm even though the furniture factory was located in what was then a “suburb” outside the city limits.

After the firefighters arrived Keniff rushed into the factory’s machine building with them and helped to close the fire door to contain the fire. He then joined the bucket brigade alongside three firefighters from Company B.

Those fighting the fire, both professionals and volunteers, faced three challenges—two certain and one potential.

The first certain challenge was the nature of this fire. A furniture factory naturally stores several kinds of flammable liquids in addition to its inventory of flammable wood, cotton, cloth, and excelsior.

The second certain challenge was location. Because the furniture factory was not in the city, the nearest fire plug was located at West 7th Street and Summit Avenue—a mile away. Firemen quickly laid out five thousand feet of hose from that plug westward along West 7th Street.

They came up two hundred feet short.

One of the fire companies rushed back to its station (no. 5 on Bryan Avenue) on Tucker’s Hill on the near South Side to retrieve two hundred feet of hose. The Fort Worth Record said that mile of hose was the most ever laid out for a Fort Worth fire to that date.

Even with a steam pumper engine at the fire plug, the Record reported, by the time the water from the fire plug reached the furniture factory, the stream of water was “thin and feeble.”

The potential challenge to firefighters was the Empire grain elevator, located just one block from the furniture factory along the west side of the Frisco track. If the fire spread to the elevator, grain dust is highly combustible.

F is the furniture factory. E is the Empire grain elevator. P is the fire plug. K is Keniff’s home on Stove Foundry Road. (Burleson Avenue is today’s University Drive. North Street is today’s Lancaster Avenue.)

F is the furniture factory. E is the Empire grain elevator. P is the fire plug. K is Keniff’s home on Stove Foundry Road. (Burleson Avenue is today’s University Drive. North Street is today’s Lancaster Avenue.)

Five more fire companies were dispatched as firefighters sought to contain the fire.

In the machine building Frank Keniff and the rest of the bucket brigade worked in hellish conditions. The building had become an oven. Around them smoke swirled. Over their heads rafters burned. Brick walls and metal machinery were too hot to touch, the very air almost too hot to breathe.

Suddenly the men heard a sharp crack and a roar.

Fire Captain Frank Bishop shouted, “Watch out, men! Back!”

The other men in the bucket brigade retreated as a wall collapsed toward them.

Keniff turned to retreat but was too late.

He screamed as he was buried beneath an avalanche of red-hot bricks and burning timbers.

The men who had retreated in time were showered with falling debris but uninjured.

They rushed to the mound of debris where Keniff had been buried.

Fire Chief Bideker led the attempt to rescue Keniff. As Bideker and others dug through hot bricks and burning timbers, other firefighters and volunteers continued to fight the fire with the limited water from the fire plug and the bucket brigade.

As the burning buildings were weakened, more walls threatened to collapse. Firefighters stood on one burning roof and used a long iron pipe to push over a weakened two-story brick wall before it could collapse on someone.

Meanwhile, as Bideker and his crew worked to rescue Keniff, at first they could hear his moaning. But his voice grew weaker and weaker.

Then silence.

Elsewhere in the factory, the draft created by the fire sent incandescent sheets of tin from the roof of the buildings sailing into the air. Some landed hundreds of feet away.

By now the flames and smoke were visible all over town. Nearby City Park (now Trinity Park) was “bright as day,” the Record wrote, and “weird and fantastic shadows were cast” by the “lurid tongues of flame leaping heavenward.”

Gawkers rode the Summit and Arlington Heights streetcars to the scene to watch the conflagration. Because the furniture plant was not located in the city limits, Fort Worth police had not responded, allowing the crowd of onlookers to get closer.

Finally, after almost an hour of digging, Bideker and his crew reached Frank Keniff. He was crushed and burned and suffocating but still alive.

An ambulance was already waiting.

In the crowd of onlookers was a man from the medical college founded by Fort Worth University. He felt Keniff’s pulse. It was, like the water from the fire plug, “thin and feeble.”

“Boys, he’s still alive. Bring me some whisky.”

A railroad man lent a bottle, and whisky was administered.

Keniff clung to life as he was loaded into the ambulance but was declared dead at the hospital.

The fire was brought under control after three hours, but in the varnish and finishing buildings of the factory the fire burned all night.

These reports are from the Record and the Dallas Morning News.

An insurance company placed this ad next to the Record news story about the fire.

An insurance company placed this ad next to the Record news story about the fire.

The furniture company’s initial estimate of $100,000 ($2.6 million today) in losses was later cut in half.

The president of the company said the burned buildings would be replaced with fireproof buildings.

W. S. Weston, superintendent of the Parmley & Nethercut concrete pipe plant, said of Frank Keniff: “He was one of the best workers I ever saw, always willing to work, and never satisfied until he was busy.”

The furniture company and the concrete pipe company paid for Keniff’s funeral.

The furniture company and the concrete pipe company paid for Keniff’s funeral.

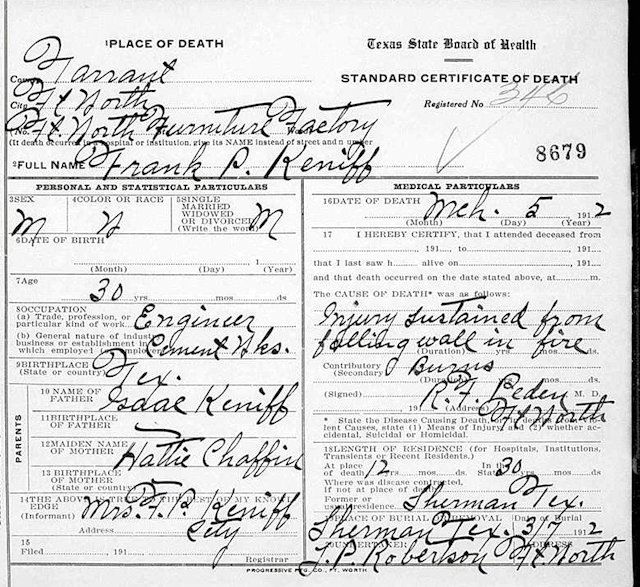

Frank Keniff was thirty years old, had moved to Fort Worth from Sherman. He had worked as a laborer, painter, carpenter, furniture repairer, and most recently as a civil engineer for Parmley & Nethercut.

Frank Keniff was thirty years old, had moved to Fort Worth from Sherman. He had worked as a laborer, painter, carpenter, furniture repairer, and most recently as a civil engineer for Parmley & Nethercut.

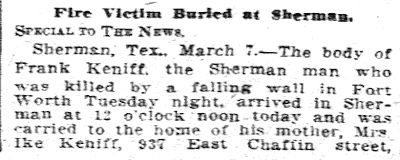

Frank Keniff was buried in Sherman.

Frank Keniff was buried in Sherman.

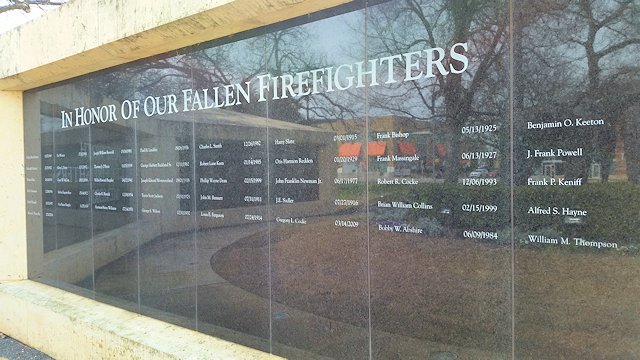

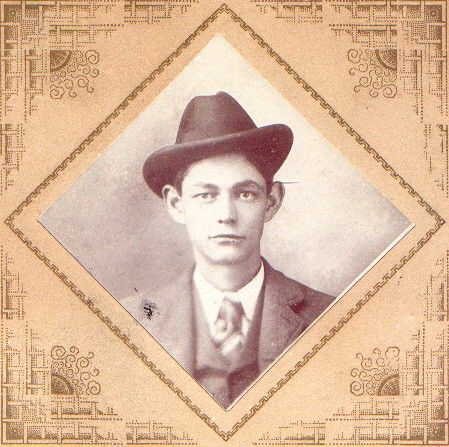

Frank Keniff is honored at the Fort Worth Police and Firefighters Memorial in Trinity Park. The memorial is located a quarter-mile from where he died. (Keniff family photo from Kathy Freeburger.)

Frank Keniff is honored at the Fort Worth Police and Firefighters Memorial in Trinity Park. The memorial is located a quarter-mile from where he died. (Keniff family photo from Kathy Freeburger.)

Keniff’s name is inscribed above that of another civil engineer who was the sole fatality of a Fort Worth fire.

Keniff’s name is inscribed above that of another civil engineer who was the sole fatality of a Fort Worth fire.

(Thanks to retired Fort Worth police sergeant and historian Kevin Foster for his help.)