The two men were born one hundred miles and seven years apart after the Civil War ended. Seven hundred miles and forty-five years later, as a new war began, the two men would die just minutes apart at the same rolltop desk in an office in Fort Worth’s city hall.

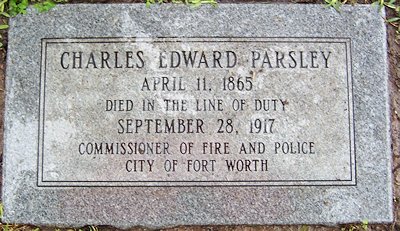

Charles Edward Parsley was born in Marshall County, Tennessee on April 11, 1865, two days after the Civil War ended.

James Kidwell Yates was born in White County, Tennessee in 1872.

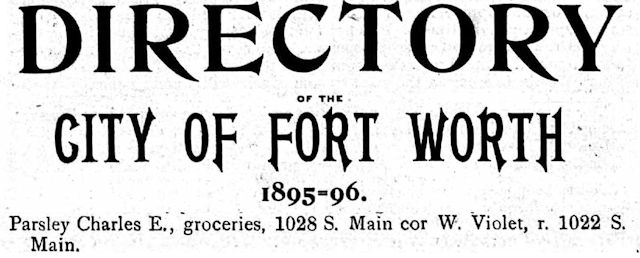

By 1895 Ed Parsley was in Fort Worth, a grocer on South Main Street.

By 1895 Ed Parsley was in Fort Worth, a grocer on South Main Street.

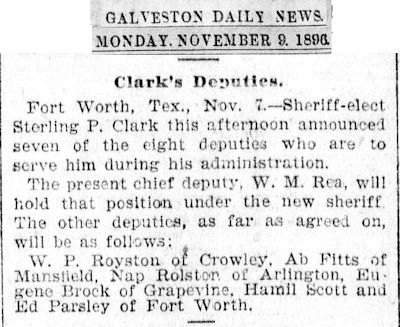

But the next year he was appointed deputy sheriff by incoming Sheriff Sterling P. Clark. (Also appointed deputy sheriff was Hamil Scott, who would be killed in the line of duty in 1907.)

But the next year he was appointed deputy sheriff by incoming Sheriff Sterling P. Clark. (Also appointed deputy sheriff was Hamil Scott, who would be killed in the line of duty in 1907.)

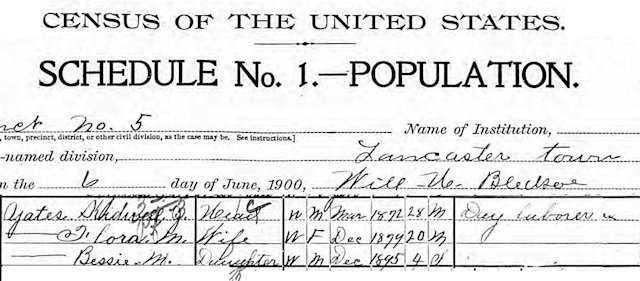

By 1900 James Yates was a day laborer in Lancaster in Dallas County. Now Parsley and Yates were only thirty miles apart.

By 1900 James Yates was a day laborer in Lancaster in Dallas County. Now Parsley and Yates were only thirty miles apart.

Yates was married now, with a four-year-old daughter.

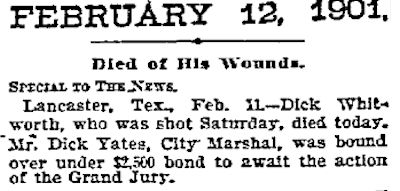

In 1901 Yates became a city marshal in Lancaster and had not been on the job long when he shot a man to death. According to Written in Blood by historian Dr. Richard Selcer and retired Fort Worth police sergeant and historian Kevin Foster, Yates had previously arrested the man, Dick Whitworth, and Whitworth had threatened to get even. Preemptively, Yates went looking for Whitworth, found him, shot him four times, and turned himself in. Yates was no-billed by a grand jury.

In 1901 Yates became a city marshal in Lancaster and had not been on the job long when he shot a man to death. According to Written in Blood by historian Dr. Richard Selcer and retired Fort Worth police sergeant and historian Kevin Foster, Yates had previously arrested the man, Dick Whitworth, and Whitworth had threatened to get even. Preemptively, Yates went looking for Whitworth, found him, shot him four times, and turned himself in. Yates was no-billed by a grand jury.

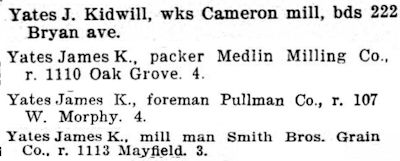

James Yates moved to Fort Worth about 1903 and between 1904 and 1910 worked at a series of jobs, three of them at flour mills. (Elizabeth Street was two blocks south of East Vickery Boulevard.) Now James Yates and Ed Parsley were in the same town, both living on the South Side.

James Yates moved to Fort Worth about 1903 and between 1904 and 1910 worked at a series of jobs, three of them at flour mills. (Elizabeth Street was two blocks south of East Vickery Boulevard.) Now James Yates and Ed Parsley were in the same town, both living on the South Side.

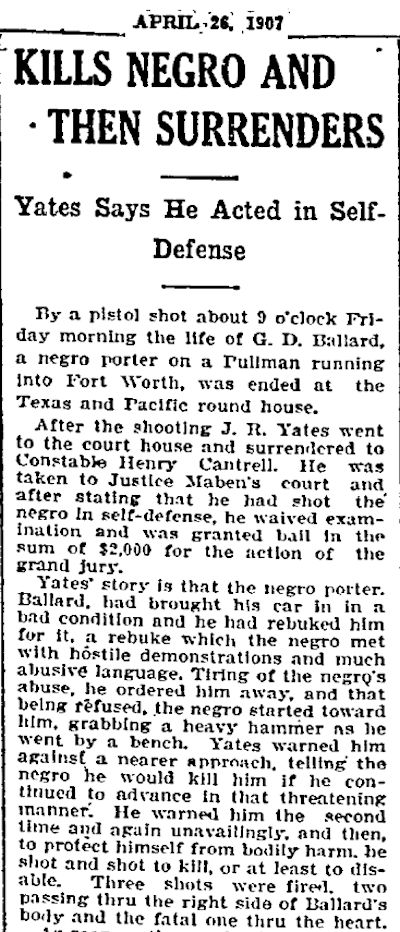

While working for the Pullman company in 1906 Yates shot to death porter G. D. Ballard. As with the Whitworth shooting, Yates turned himself in. He claimed self-defense, saying Ballard had threatened him with a hammer after the two men had argued. The case was dismissed because no witnesses could be secured.

While working for the Pullman company in 1906 Yates shot to death porter G. D. Ballard. As with the Whitworth shooting, Yates turned himself in. He claimed self-defense, saying Ballard had threatened him with a hammer after the two men had argued. The case was dismissed because no witnesses could be secured.

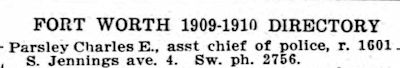

Meanwhile Ed Parsley had moved from the sheriff’s department to the police department and was advancing his career: By 1909 he was an assistant chief.

Meanwhile Ed Parsley had moved from the sheriff’s department to the police department and was advancing his career: By 1909 he was an assistant chief.

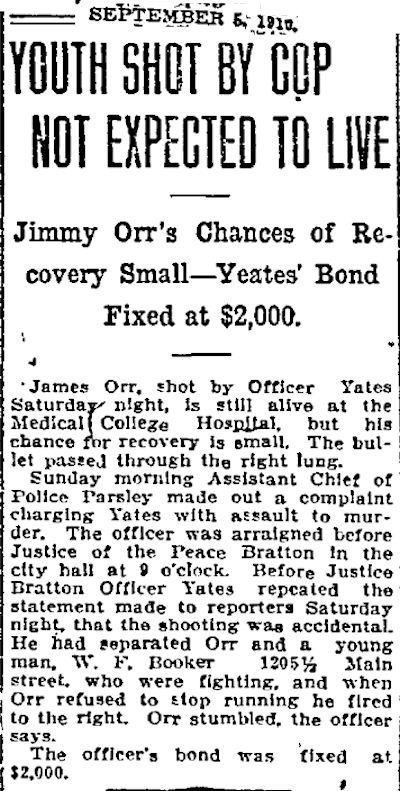

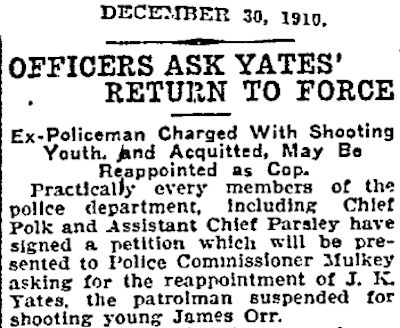

In 1910 Yates joined the Fort Worth police department. Now James Yates and Ed Parsley were brothers in blue. And just as at Lancaster, James Yates had not been on the job long when he was in the news. While on patrol in Hell’s Half Acre one night Yates had come upon two youths fighting. He broke up the fight, but one youth ran away. The fleeing youth was unarmed, but rather than chase him, Yates fired at him, later claiming that he had fired to the right of the fleeing youth but that the youth had stumbled into the path of the bullet, which passed through his right lung. Now the lives of James Yates and Ed Parsley crossed as Assistant Police Chief Parsley charged Yates with assault to murder and suspended him from the force.

In 1910 Yates joined the Fort Worth police department. Now James Yates and Ed Parsley were brothers in blue. And just as at Lancaster, James Yates had not been on the job long when he was in the news. While on patrol in Hell’s Half Acre one night Yates had come upon two youths fighting. He broke up the fight, but one youth ran away. The fleeing youth was unarmed, but rather than chase him, Yates fired at him, later claiming that he had fired to the right of the fleeing youth but that the youth had stumbled into the path of the bullet, which passed through his right lung. Now the lives of James Yates and Ed Parsley crossed as Assistant Police Chief Parsley charged Yates with assault to murder and suspended him from the force.

Despite the dire “Not Expected to Live” headline above, the shooting victim did live. And as in Lancaster, James Yates was not tried for the shooting. Ed Parsley, who had suspended Yates, was among police officers who signed a petition urging that Yates be reinstated to the police force.

Despite the dire “Not Expected to Live” headline above, the shooting victim did live. And as in Lancaster, James Yates was not tried for the shooting. Ed Parsley, who had suspended Yates, was among police officers who signed a petition urging that Yates be reinstated to the police force.

He was.

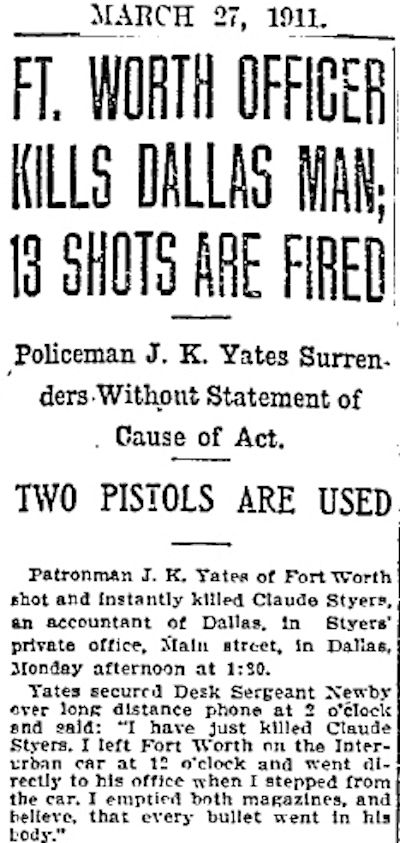

In 1911 Yates killed another man. This time he was acting as a private citizen, not a police officer. In Dallas he fired thirteen bullets into accountant Claude Styers.

In 1911 Yates killed another man. This time he was acting as a private citizen, not a police officer. In Dallas he fired thirteen bullets into accountant Claude Styers.

As with the Whitworth killing, Yates turned himself in: He went to the sheriff’s office and calmly telephoned the Fort Worth police department, told the desk sergeant what he had done, and asked that Police Chief June Polk come to Dallas so that Yates could “fix everything all right with him.” Yates offered no explanation for the shooting.

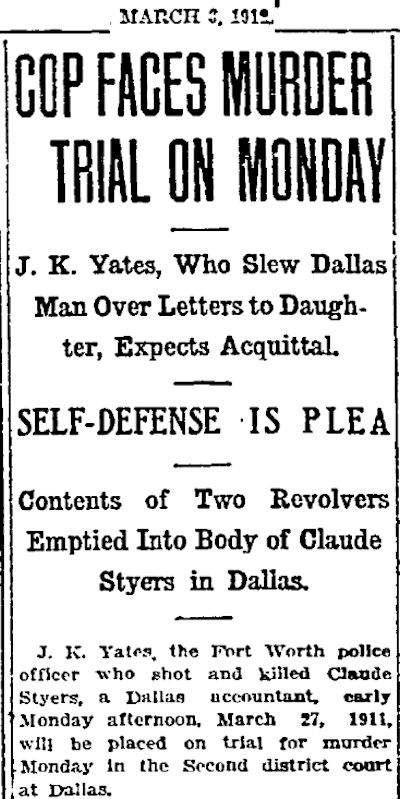

But at his trial Yates pleaded self-defense and cited “the unwritten law.” Yates had accused Styers of the “ruin” of his daughter Bessie. According to the Buffalo Law Review, the unwritten law was an uncodified constraint that protected “those who killed to defend the honor of women. . . . a husband, brother, or father could justifiably kill any man who had a sexual relationship outside of marriage with the killer’s wife, daughter, sister, or mother.”

But at his trial Yates pleaded self-defense and cited “the unwritten law.” Yates had accused Styers of the “ruin” of his daughter Bessie. According to the Buffalo Law Review, the unwritten law was an uncodified constraint that protected “those who killed to defend the honor of women. . . . a husband, brother, or father could justifiably kill any man who had a sexual relationship outside of marriage with the killer’s wife, daughter, sister, or mother.”

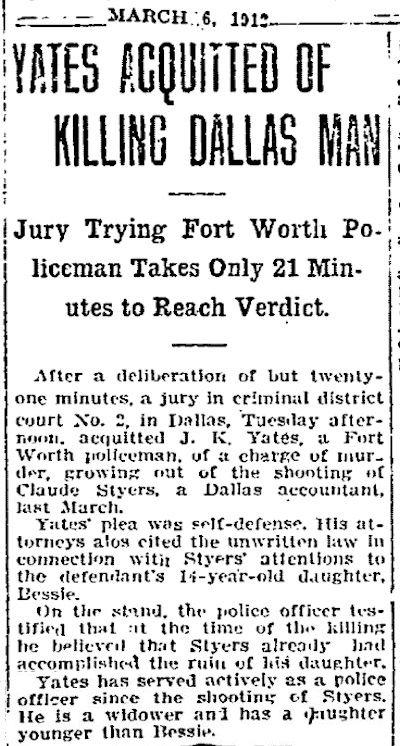

As with the Whitworth killing, Yates was cleared in the killing of Styers. Note that by now Yates was a widower.

As with the Whitworth killing, Yates was cleared in the killing of Styers. Note that by now Yates was a widower.

In 1915 newly elected Police Commissioner M. W. Hurdleston instituted changes in the police department. James Yates was one of four officers assigned to mounted patrol at the Missouri Avenue station because the unpaved streets of the South Side made patrolling on bicycle dangerous.

In 1915 newly elected Police Commissioner M. W. Hurdleston instituted changes in the police department. James Yates was one of four officers assigned to mounted patrol at the Missouri Avenue station because the unpaved streets of the South Side made patrolling on bicycle dangerous.

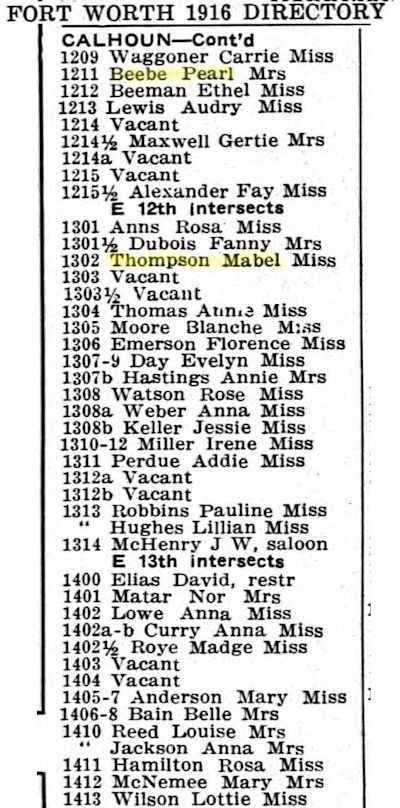

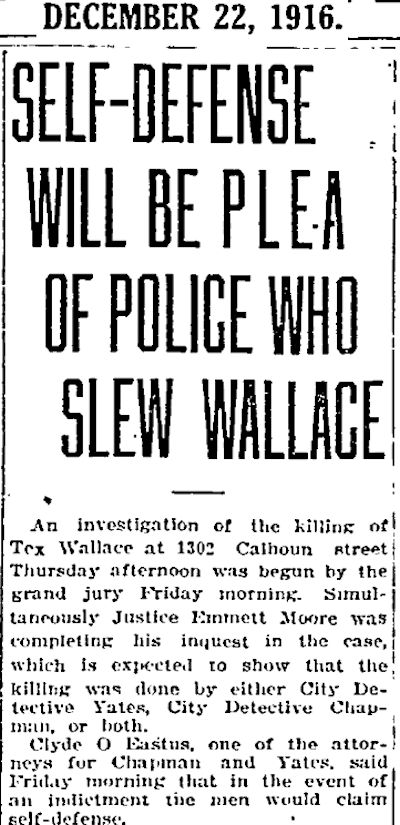

Fast-forward to 1916. Another year, another killing. Tex Wallace, forty, was an accomplished yeggman (safecracker) with a prolific arrest record. Recently he had grown weary of being hauled in by police and had begun to make threats against officers. Two of those officers were James Yates (by now a detective) and George Chapman. As he had with Dick Whitworth, Yates acted preemptively. On December 21 he and Chapman went to the brothel of Mabel Thompson at 1302 Calhoun Street in the Acre.

Note the high percentage of Misses in Mabel’s stretch of Calhoun Street in 1910. (One Mrs. was Pearl Beebe, a madam who is buried in Soiled Doves Row at Oakwood Cemetery.)

Note the high percentage of Misses in Mabel’s stretch of Calhoun Street in 1910. (One Mrs. was Pearl Beebe, a madam who is buried in Soiled Doves Row at Oakwood Cemetery.)

Mabel’s brothel was Tex Wallace’s second home. Detectives Yates and Chapman entered Mabel’s brothel and walked back to the room containing a dance floor. Sure enough, there was Wallace, dancing with one of Mabel’s misses. According to Yates and Chapman, when Wallace saw them he moved his hand toward his hip pocket. Fearing that Wallace was reaching for a gun, Yates and Chapman later claimed, they shot Wallace six times.

Tex Wallace was not armed.

The miss with whom Wallace was dancing told a different story. She claimed that Yates, before shooting Wallace, had called out a warning to her and had pulled her out of the line of fire.

As with the Whitworth, Ballard, and Styers killings, Yates turned himself in. He and Chapman were charged with murder. But as with the Whitworth, Ballard, and Styers killings, Yates was not indicted.

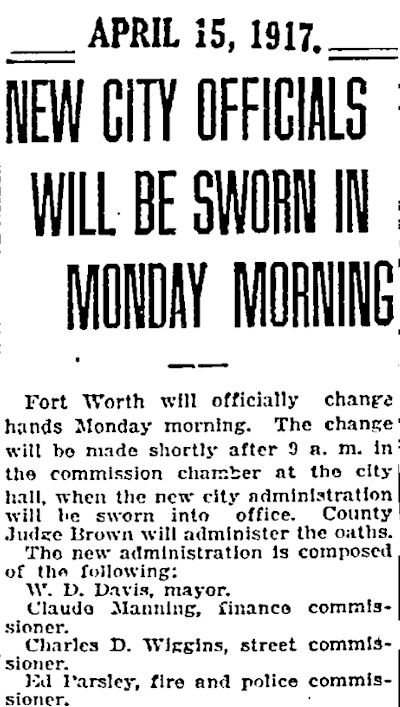

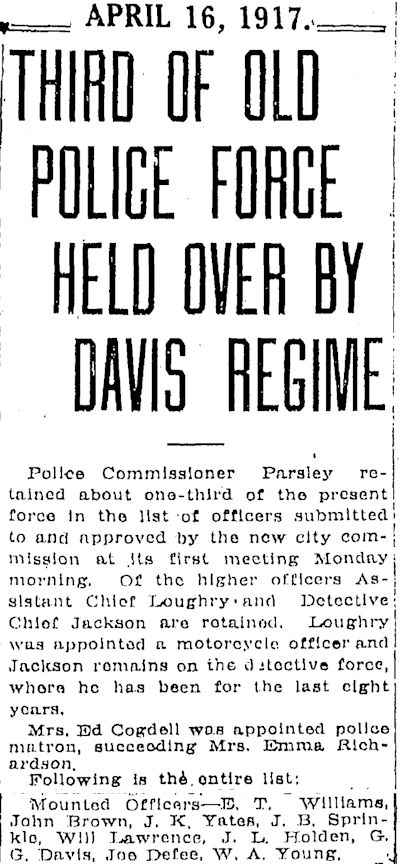

On April 16, 1917, ten days after America declared war on Germany, Charles Edward Parsley’s star was rising: He was sworn in as Fort Worth’s police and fire commissioner.

On April 16, 1917, ten days after America declared war on Germany, Charles Edward Parsley’s star was rising: He was sworn in as Fort Worth’s police and fire commissioner.

That same day, James Kidwell Yates’s star was falling: Parsley began putting his stamp on the two departments under his supervision, dismissing some people, promoting and demoting others. Among those demoted was detective James Yates, now busted back where he had been in 1915: mounted patrol on the South Side.

That same day, James Kidwell Yates’s star was falling: Parsley began putting his stamp on the two departments under his supervision, dismissing some people, promoting and demoting others. Among those demoted was detective James Yates, now busted back where he had been in 1915: mounted patrol on the South Side.

Yates resented the demotion. He also resented having to buy a horse, which mounted patrolmen were required to do.

Yates resented the demotion. He also resented having to buy a horse, which mounted patrolmen were required to do.

He resigned.

Soon after, Yates joined a detective agency that had been formed by another recently released officer.

Soon after, Yates joined a detective agency that had been formed by another recently released officer.

But James Kidwell Yates brooded. He nursed a grudge like a baby nurses a bottle.

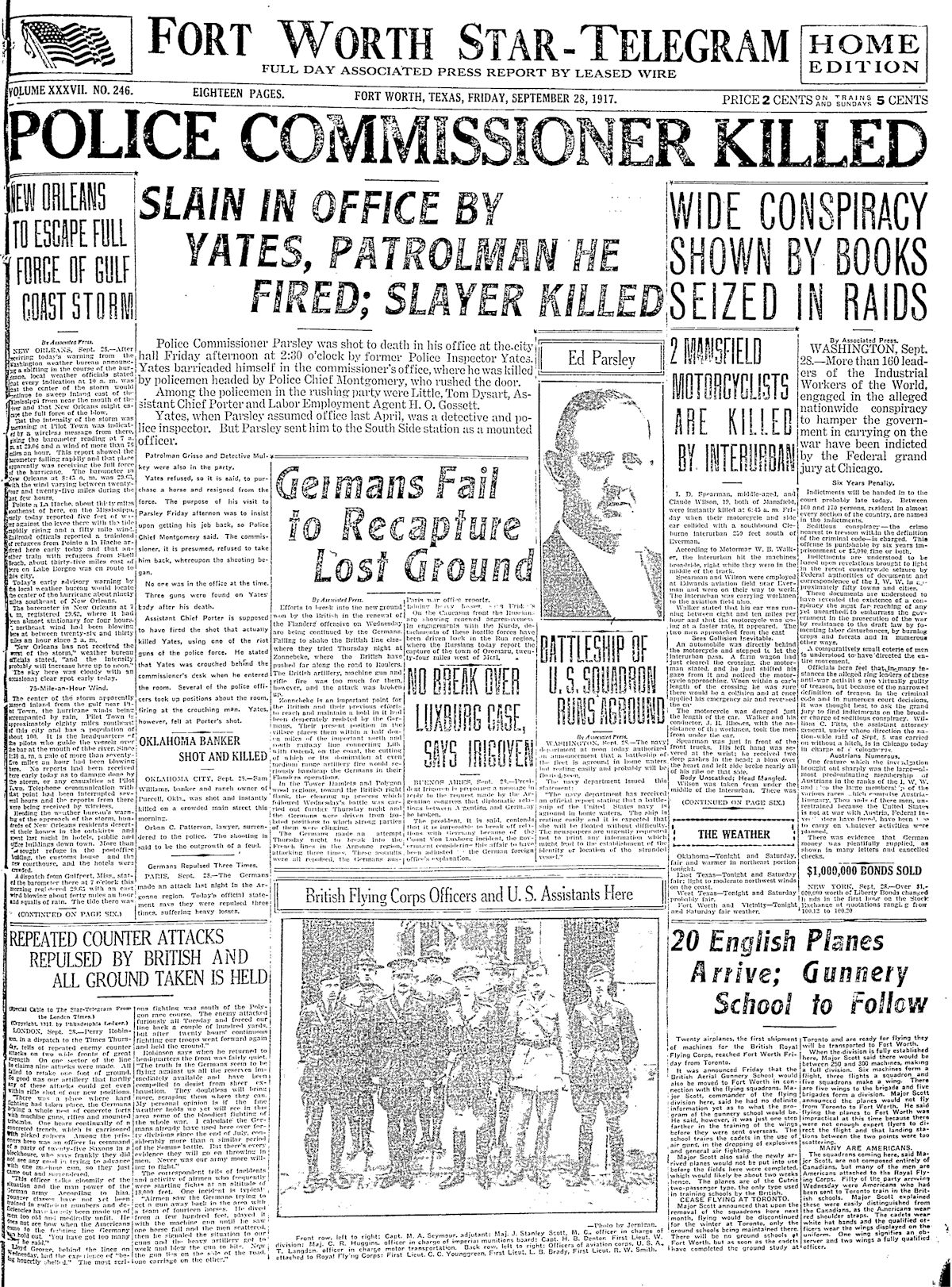

On September 28, 1917 Charles Edward Parsley had been in his new position less than six months when Yates walked into city hall on Throckmorton Street. According to the Star-Telegram, Yates first went to the reception room outside the private office of Mayor W. D. Davis and asked to see Davis. W. T. Coleman, city weights and measures inspector, was in the reception room at the time. Coleman later said: “Knowing he [Yates] was vexed because of not getting the position he wanted, and knowing his past record, I decided to keep him from the mayor if possible and avoid trouble.”

Even though Mayor Davis was in his private office talking with a friend, Coleman told Yates that the mayor was not in his office and would be gone an hour. Yates said he’d wait and sat down in the reception room. As Yates sat there so close to the mayor’s private office, Coleman feared that Yates would hear the mayor’s voice and realize he had been lied to.

But after a few minutes Yates got up and left the reception room.

Moments later Coleman heard two loud gunshots. Coleman ran into the mayor’s office and asked Davis if he was armed. “No,” the mayor said. “What is the matter?”

Coleman said, “Yates has just killed someone, likely Parsley.”

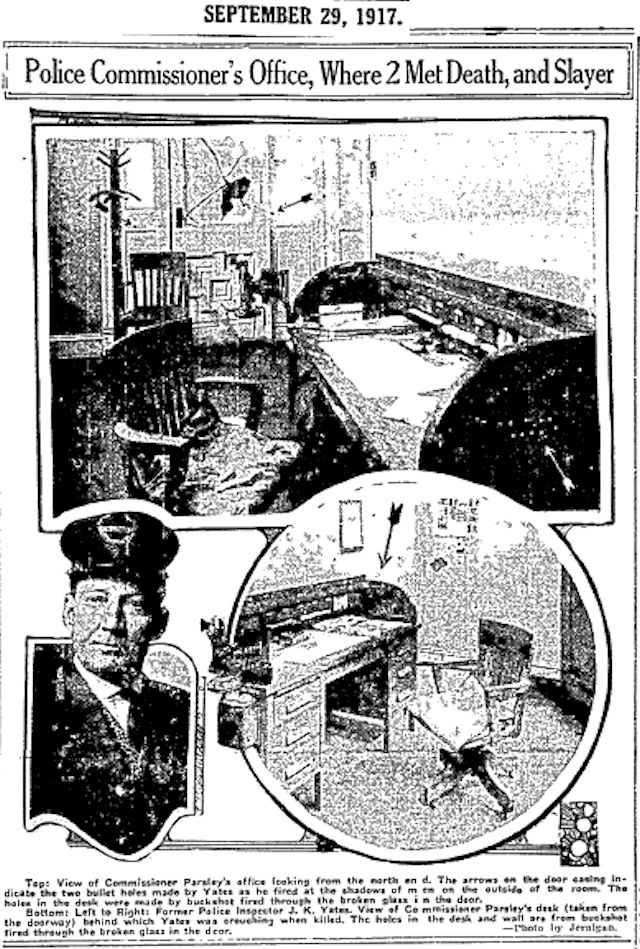

Indeed, the Star-Telegram reported, Yates had walked into Parsley’s office, found it unoccupied, then through a window saw Parsley standing on the steps of city hall and summoned him. After Parsley entered his office, Yates apparently without any exchange of words shot Parsley first in the back and then in the head. Parsley collapsed near his rolltop desk. As police officers and others in city hall reacted to the sound of gunshots, Yates remained in the office with Parsley’s body on the floor and the door locked. Yates crouched behind Parsley’s desk and kept his eyes fixed on the frosted glass panel of the door.

Soon Yates saw silhouettes on that frosted glass panel: Men were standing on the other side of the door. He fired several shots through the door, wounding an officer in the hall.

As Yates hunkered behind his rolltop palisade, he could not hear the riot guns being handed out in the hall. One of those guns went to Assistant Police Chief Rufus Porter, who stationed himself at the door to the office of Police Chief Oscar Montgomery, sixteen feet from the door to Parsley’s office. Yates’s gunfire had shattered the frosted glass panel of the door to Parsley’s office, giving Porter a “window” of four or five inches in the frosted glass panel, the Star-Telegram wrote. Porter sighted down the barrel of his riot gun through that window and waited. All he could see was the rolltop desk. Crouched behind the rolltop desk, Yates was out of view of people on the other side of the door.

Meanwhile ten officers and other city employees had assembled in the hall, heavily armed and waiting for the order to storm Parsley’s office.

Rufus Porter, too, bided his time. Suddenly through his tiny window in the door he saw the top of a felt hat appear above the rolltop desk. But Porter waited. Then Yates’s forehead was visible above the desk. Again Porter waited. Then he saw the green eyeglasses that Yates wore. Still Porter waited. If he could see Yates, could Yates see him? Porter, like everyone else on the force, knew Yates’s reputation. Yates was a quick and accurate shot and a remorseless killer.

Porter sighted down his gun barrel through his window as, with excruciating slowness, Yates lifted his head another inch above the rolltop desk.

Porter saw Yates’s nose.

Rufus Porter fired two shots—one through the desk into Yates’s obscured torso and one at Yates’s exposed head. Yates crumpled onto the floor behind the desk.

The silence was broken only by ragged breathing in the hall as men exhaled.

One of those men called to Yates.

No reply.

At a signal, men armed with riot guns and led by Chief Montgomery charged through the door into Parsley’s office, firing several shots at Yate’s sprawled body as they entered the room. He was dead.

Twelve feet away lay the body of Charles Edward Parsley.

The room, the Star-Telegram wrote, looked like “the scene of a pitched battle.” The desk and walls were perforated with bullet holes.

Gunsmoke and plaster dust swirled in the air.

How did it get that far?

How did it get that far?

The police department had known that Yates was a loose cannon. The Star-Telegram reported that for several weeks after Yates was demoted and resigned, he had “threatened several times to come to the city hall and make a general ‘cleanup’ by killing Mayor Davis, Commissioner Parsley, Chief Montgomery, and Detective Chief Connelley. Both Porter and Montgomery had been warned of this threat of Yates, and efforts had been made to calm him down.”

Upon his death Yates was found to be armed with three large-caliber revolvers and “many extra cartridges,” the Star-Telegram wrote.

Chief Montgomery said afterward, “Well, boys, he came ready for all of us, as he said he would.”

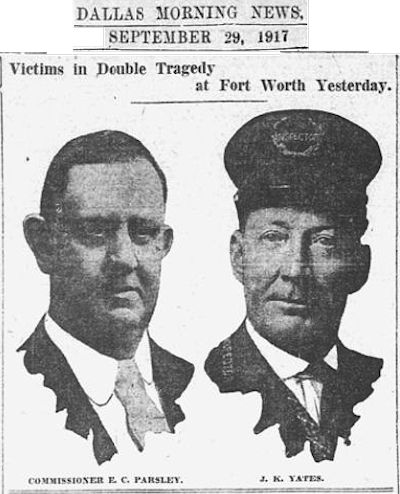

Photo montage shows Commissioner Parsley’s rolltop desk, where first Parsley and then James Yates (pictured) were fatally shot.

Photo montage shows Commissioner Parsley’s rolltop desk, where first Parsley and then James Yates (pictured) were fatally shot.

More than three thousand people attended the funeral for Charles Edward Parsley. He is buried in Greenwood Cemetery.

More than three thousand people attended the funeral for Charles Edward Parsley. He is buried in Greenwood Cemetery.

James Kidwell Yates is buried in Lancaster.

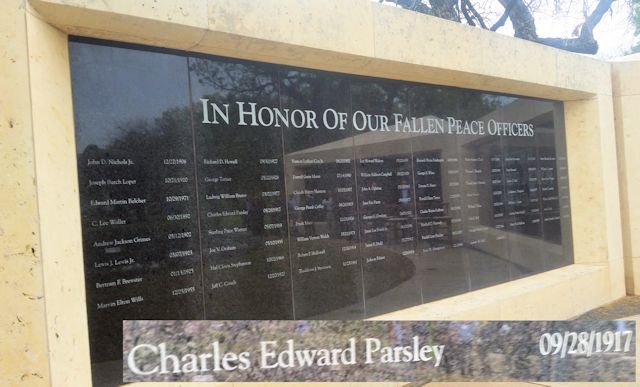

Police and Fire Commissioner Charles Edward Parsley is the highest-ranking officer honored at the Fort Worth Police & Firefighters Memorial in Trinity Park.

Police and Fire Commissioner Charles Edward Parsley is the highest-ranking officer honored at the Fort Worth Police & Firefighters Memorial in Trinity Park.

The killing of the Pullman porter sounds fishy. Those “negro” porters coveted their jobs, knew how to serve, and knew how to abase themselves when dealing with hostile white people.Yates’ sociopathic tendencies showed up and the porter ended up dying. No way Yates does time for killing a negro in any kind of confrontation. He gets a taste of blood and wants more. Mr. Parsley was a victim of Yates’ immunity to prosecution.

I AM PROUD TO BE THE GRAND NEPHEW OF ED PARSLEY. HE WAS WELL LOVED BY ALL OF US.HE MADE A DIFFERENCE WITH HIS LIFE. I,JAMES H. PARSLEY HAVE DISTINGUISHED THE FAMILY BY BEING THE RECIPIENT OF THE CONGRESSIONAL GOLD MEDAL OF HONOR.I AM 96 MY EMAIL [email protected]