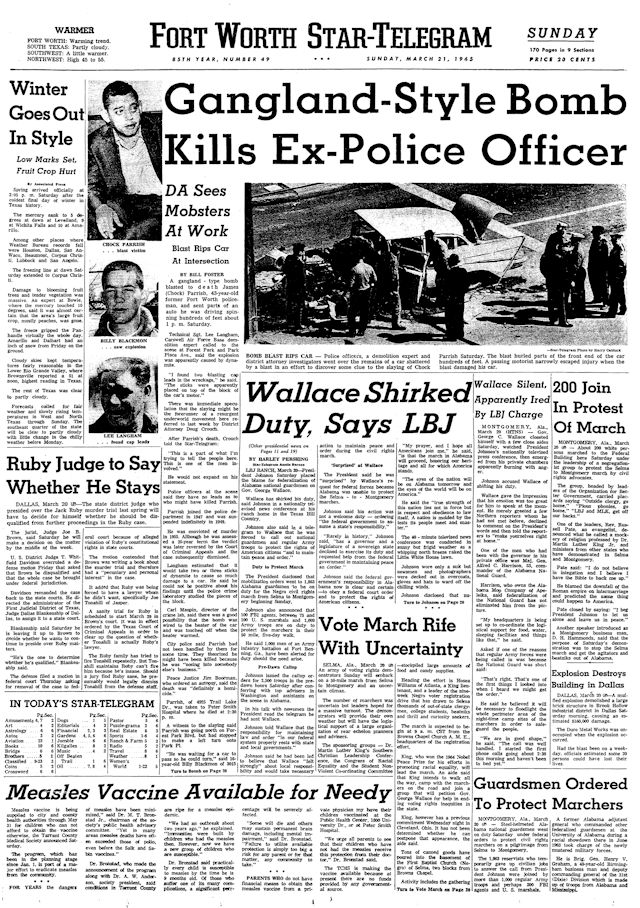

The spring of 1965 began like it was the 1950s on Jacksboro Highway. It had all the elements of the old days: a car-bombing, a drive-by assassination, warnings of an underworld resurgence, a Cadillac loaded with weapons, a vendetta, accusations of bribery, missing cash, front-page headlines.

The only missing element was a woman whom the newspapers described in breathless terms.

No, wait. Got that, too.

Now we’re all set for March 20, 1965.

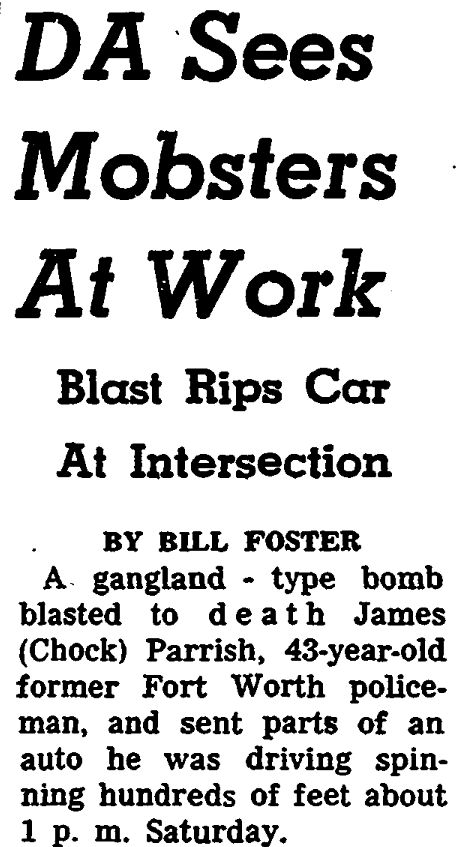

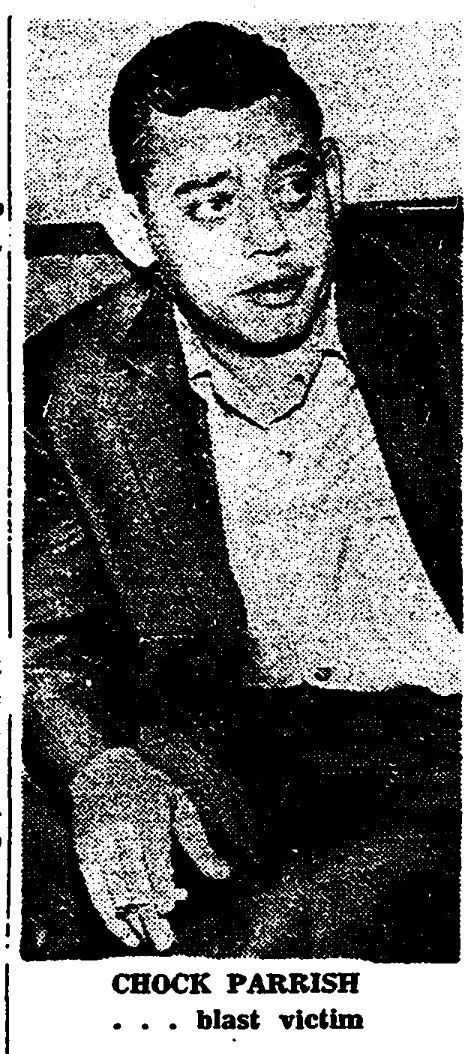

It was a cold day with a high in the 40s. And that cold would be the death of James (“Chock”) Parrish.

Just before 1 p.m. Parrish, forty-three, drove away from Burkett’s Recreation Club on Hemphill Street. He turned on his car’s heater. A few minutes later he was driving north on Forest Park Boulevard. At Park Place Avenue he yielded to an oncoming car before turning west onto Park Place.

The 1957 Chevy that Parrish was driving would never get a chance to become a classic: As the oncoming car passed, the Chevy exploded. The front end of the car, a witness said, was jolted eight feet off the pavement. Glass and metal were thrown into trees hundreds of feet away. The windshield of the passing car was blown out, the car’s hubcaps blown off.

The 1957 Chevy that Parrish was driving would never get a chance to become a classic: As the oncoming car passed, the Chevy exploded. The front end of the car, a witness said, was jolted eight feet off the pavement. Glass and metal were thrown into trees hundreds of feet away. The windshield of the passing car was blown out, the car’s hubcaps blown off.

The driver of the passing car was not injured but later said of the blast: “I thought it was going to rock my car over.”

At 2225 Edwin Street two blocks away the resident said the blast blew open the doors of his house.

A pedestrian who rushed to the scene said Parrish looked at his mutilated legs and said, “Now I know I’m dead.”

Ninety minutes later he was.

A relative said Parrish had feared for his life and had employed a bodyguard for the last three weeks but was alone when he took his last drive.

Investigators said three or four sticks of dynamite had been planted at the rear of the car’s engine. The police crime lab director said the dynamite probably “was wired to the heater of the car and was touched off when the heater warmed.”

Investigators said three or four sticks of dynamite had been planted at the rear of the car’s engine. The police crime lab director said the dynamite probably “was wired to the heater of the car and was touched off when the heater warmed.”

Parrish had been a Fort Worth motorcycle police officer from 1947 to 1949 but had been suspended (first for “buzzing” houses in an airplane and later for being AWOL). Gradually he spiraled down into the underworld.

On May 16, 1955 Parrish, Charlie Bob Eggleston (brother of Tincy), Wilcie T. (“Blackie”) Matthews, and other gamblers held a dice game at Matthews’s tourist court on East Belknap Street. Parrish accused Matthews of cheating, pulled a pistol, and shot him to death. (Matthews in 1952 had been acquitted of fatally shooting his wife as she sat on the toilet in their home.)

On May 16, 1955 Parrish, Charlie Bob Eggleston (brother of Tincy), Wilcie T. (“Blackie”) Matthews, and other gamblers held a dice game at Matthews’s tourist court on East Belknap Street. Parrish accused Matthews of cheating, pulled a pistol, and shot him to death. (Matthews in 1952 had been acquitted of fatally shooting his wife as she sat on the toilet in their home.)

Parrish was convicted of murder, but the conviction was overturned after the defense’s star witness, Joseph Wilson (“Happy Jack”) Jones, described by one newspaper as “a slot machine ‘pirate,’” was shot to death in 1959 by another man in an argument over Jones’s estranged wife. (Note the headline “Wife Is Charged After Body Found.”)

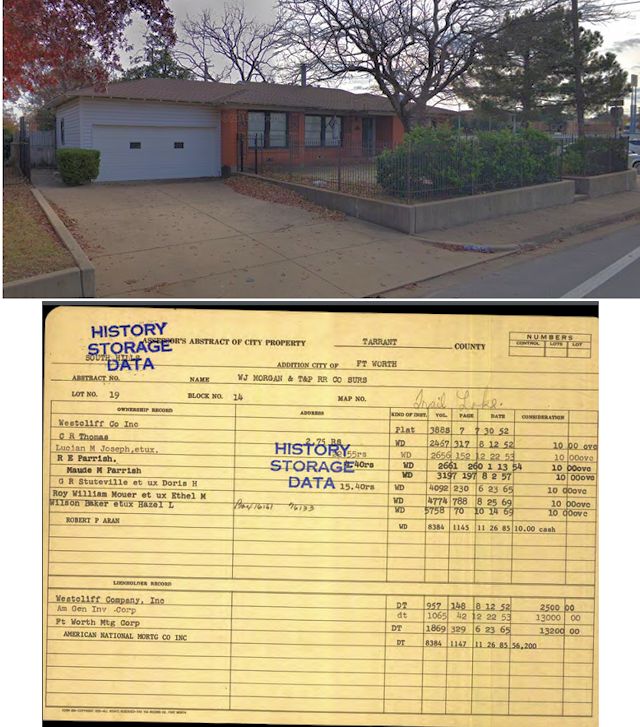

Parrish lived with his mother at 4925 Trail Lake Drive. His mother claimed she did not know what her son did for a living. The Press said he was a used car dealer.

Parrish lived with his mother at 4925 Trail Lake Drive. His mother claimed she did not know what her son did for a living. The Press said he was a used car dealer.

The 1957 Chevy that Parrish was driving was registered to the mother of Danny McComb, a former Jacksboro Highway tavern owner who had been suspected in the kidnapping of two police officers and the gang slaying of hoodlum George Kean, whose body was found in a shallow grave in Michigan in 1958.

After the Parrish bombing, police could not find Danny McComb.

McComb’s mother said, “I hope nothing’s happened to my boy.”

Underworld killings usually presented investigators with an embarrassment of riches when it came to suspects. In addition to McComb, the Press reported, police wanted to talk to local police character Coy Clark about the bombing. Clark was said to be (1) Fort Worth’s no. 1 abortionist and (2) the husband of Parrish’s girlfriend. The Press reported that City Hall sources speculated that Parrish was killed because he talked too freely about underworld activities.

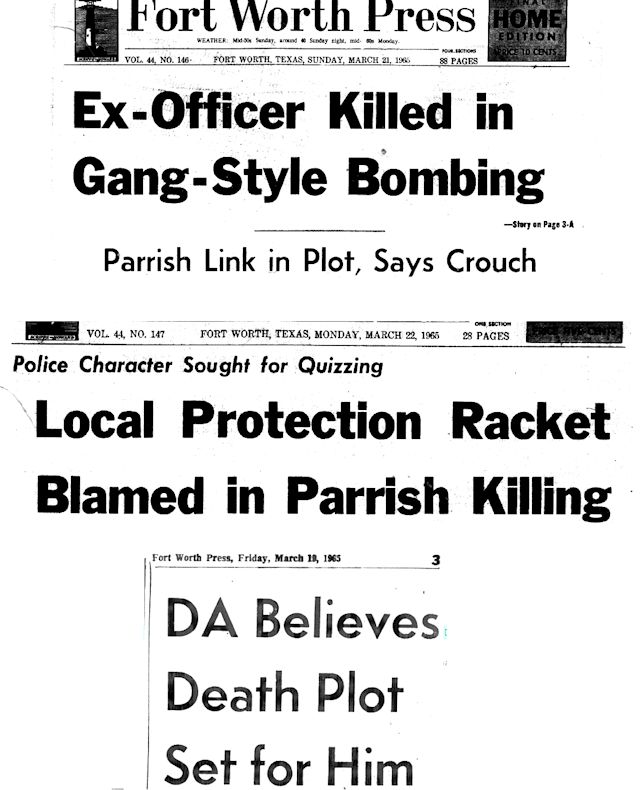

Just four days earlier District Attorney Doug Crouch had warned that a “major underworld movement” was emerging in Tarrant County. In fact, Crouch suspected that he was the target of an assassination plot (see Part 2).

Just four days earlier District Attorney Doug Crouch had warned that a “major underworld movement” was emerging in Tarrant County. In fact, Crouch suspected that he was the target of an assassination plot (see Part 2).

Crouch said the Parrish car-bombing was an example of the underworld resurgence he had warned about.

Neither Crouch nor Harry Beason, one of Crouch’s investigators, would comment when asked if the Parrish killing was linked to a plot against Crouch, although the Star-Telegram later reported that Crouch “hinted” at a link.

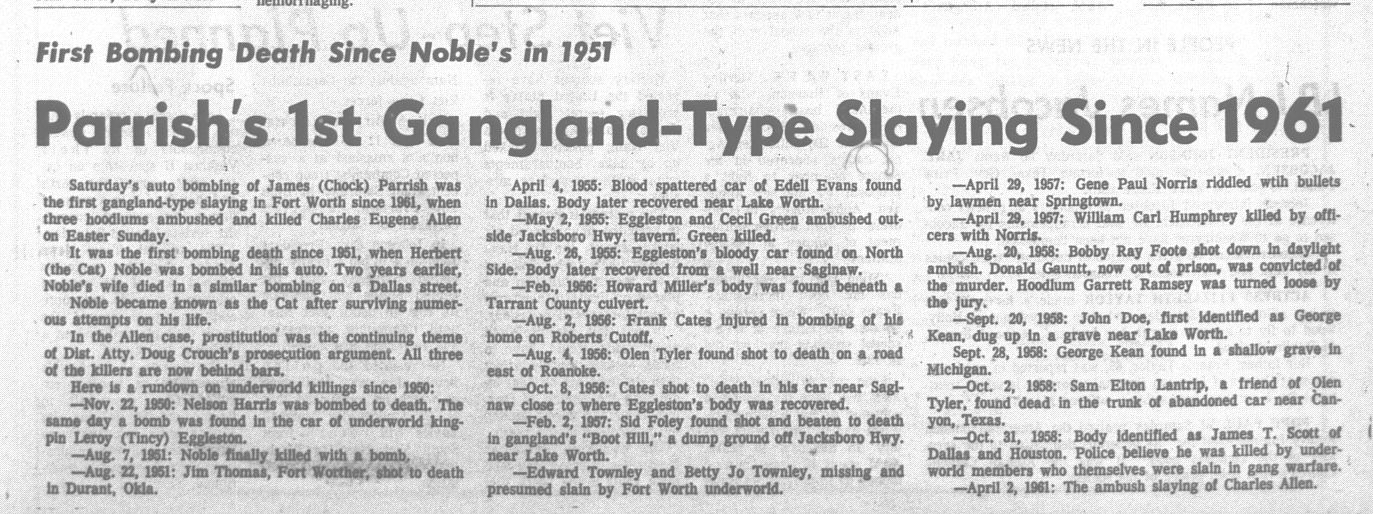

After the Parrish car-bombing the Press printed a list of gangland slayings since 1951. Many of the victims were habitues of Jacksboro Highway.

After the Parrish car-bombing the Press printed a list of gangland slayings since 1951. Many of the victims were habitues of Jacksboro Highway.

On that March 20 in 1965, when Chock Parrish turned on his car heater, and the Chevy exploded, and Parrish caught his death of cold, he apparently had been anticipating warmer weather: He had two fishing rods and a minnow bucket in the back seat of the Chevy.