The time: 1870s. The place: northern Texas. That intersection of time and place also was the intersection of physics and crime, an intersection seemingly ruled by these two corollaries to Newton’s laws of motion:

If it moves, it can be stopped, and if it can be stopped, it can be robbed.

If you lived at that intersection of time and place, your modes of transportation (beyond walking) were horse, streetcar, stagecoach, and train. And, as we shall see, in all four modes you could find yourself looking down the barrel of a gun:

In February 1879 a mail rider traveling between Breckinridge and Palo Pinto west of Fort Worth “was accosted by a highwayman, who commanded him to drop the mail-bag.” At first the rider refused. But upon “hearing the ominous ‘click’ of a pistol,” he complied. The highwayman, now in possession of the mail bag, ordered the rider to turn and ride until he was told to halt. When the rider was about fifty yards out, the highwayman told him to halt, but the rider instead “put spurs to his horse and dashed away.” The rider alerted nearby residents and described the bandit. Based on that description, a local man of twenty four was arrested. The mail rider identified the man as the robber. The suspect claimed that he had been framed by the mail rider.

In February 1879 a mail rider traveling between Breckinridge and Palo Pinto west of Fort Worth “was accosted by a highwayman, who commanded him to drop the mail-bag.” At first the rider refused. But upon “hearing the ominous ‘click’ of a pistol,” he complied. The highwayman, now in possession of the mail bag, ordered the rider to turn and ride until he was told to halt. When the rider was about fifty yards out, the highwayman told him to halt, but the rider instead “put spurs to his horse and dashed away.” The rider alerted nearby residents and described the bandit. Based on that description, a local man of twenty four was arrested. The mail rider identified the man as the robber. The suspect claimed that he had been framed by the mail rider.

Despite the word Train in the headline, “the horse cars” in which two prominent citizens were riding toward the Texas & Pacific train depot to get “a little fresh air” on the night of July 31, 1878 were horse-drawn streetcars. (Imagine complaining about air quality in 1878!) Two “rough looking men with six-shooters” entered the car and demanded money of “the two peaceable gents.” The take: ten cents (less than three dollars today). Nonetheless, B. B. Paddock’s Democrat lamented the “foul deed” and hoped “our efficient city marshal will ferret out the perpetrators.” “Jim” was City Marshal Jim Courtright. Oddly, the crime report ends with an apparent joke/ad about “brave and sagacious” Courtright bringing the “culprits” before a bar other than that of justice: “Uncle Bob” Winders’s Cattle Exchange Saloon.

Despite the word Train in the headline, “the horse cars” in which two prominent citizens were riding toward the Texas & Pacific train depot to get “a little fresh air” on the night of July 31, 1878 were horse-drawn streetcars. (Imagine complaining about air quality in 1878!) Two “rough looking men with six-shooters” entered the car and demanded money of “the two peaceable gents.” The take: ten cents (less than three dollars today). Nonetheless, B. B. Paddock’s Democrat lamented the “foul deed” and hoped “our efficient city marshal will ferret out the perpetrators.” “Jim” was City Marshal Jim Courtright. Oddly, the crime report ends with an apparent joke/ad about “brave and sagacious” Courtright bringing the “culprits” before a bar other than that of justice: “Uncle Bob” Winders’s Cattle Exchange Saloon.

On the morning of January 26, 1878 the stagecoach bound for Weatherford left Fort Worth’s El Paso Hotel carrying mail and five passengers. The driver “cracked his whip as he pulled away from the El Paso.” Less than two miles from the hotel the stagecoach passed Major Khleber Miller Van Zandt’s cottage on his farm in today’s Trinity Park as the coach headed toward its first station near Mary’s Creek west of Fort Worth.

On the morning of January 26, 1878 the stagecoach bound for Weatherford left Fort Worth’s El Paso Hotel carrying mail and five passengers. The driver “cracked his whip as he pulled away from the El Paso.” Less than two miles from the hotel the stagecoach passed Major Khleber Miller Van Zandt’s cottage on his farm in today’s Trinity Park as the coach headed toward its first station near Mary’s Creek west of Fort Worth.

Meanwhile, a “tramp” walking along the coach road near Mary’s Creek was accosted by two men who jumped out of the brush. Armed with a Winchester rifle and two six-shooters, they told him not to “utter a word or make any break” lest they “riddle him with peanuts and corn.”

Assuming their threat to be more figurative than horticultural, the tramp obeyed. The two gunmen told him that they were going to rob the stagecoach and that they would “retard his further progress” only temporarily.

Upon the sound of the approaching stagecoach the two gunmen covered their faces with handkerchiefs with eye holes and stepped into the road in front of the coach with guns leveled at the driver.

Upon the sound of the approaching stagecoach the two gunmen covered their faces with handkerchiefs with eye holes and stepped into the road in front of the coach with guns leveled at the driver.

The stagecoach stopped.

While one bandit kept his Winchester aimed at the driver, the other bandit “gathered the harvest” in the coach: three gold watches and $500 ($1,300 today). One passenger had $400 tucked in a glove that went unharvested.

The two robbers, after asking the driver if he, too, wished to contribute to their collection, escaped into the brush. They were assumed to have had horses waiting nearby and to have skedaddled for “the Nation” (Indian Territory, now part of Oklahoma).

The Democrat wrote that the manner in which the robbery was conducted showed that the “perpetrators are ‘genuine’ scholars, well schooled in the ‘biz.’”

The Democrat concluded its report with “The prospect of their capture is not flattering.”

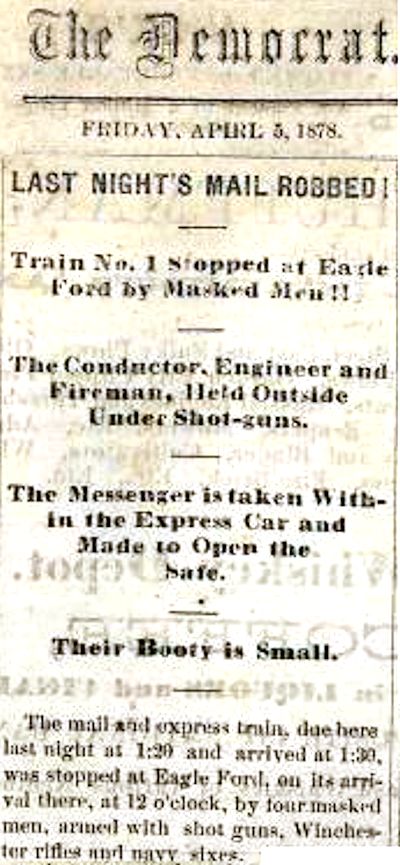

Just after midnight on April 4, 1878 the Texas & Pacific passenger train bound for Fort Worth was stopped at Eagle Ford in Dallas County when suddenly four men armed with Winchesters, shotguns, and six-shooters swarmed the train and herded the train crew onto the station platform.

Just after midnight on April 4, 1878 the Texas & Pacific passenger train bound for Fort Worth was stopped at Eagle Ford in Dallas County when suddenly four men armed with Winchesters, shotguns, and six-shooters swarmed the train and herded the train crew onto the station platform.

While three of the gang aimed guns at the train crew on the platform, the leader went to the express car. The door was locked. He demanded that the clerk inside open the door. A voice inside declined. The leader said he would force his way in.

The clerk unlocked the door. The leader greeted him with the boast that his gang had recently robbed a train at Hutchins in Dallas County.

Then the leader of the gang marched the clerk and the express car guard, “under the gentle persuasion of a rifle,” to the platform to join the rest of the hostages.

The leader returned to the express car, found the safe locked, went back to the platform to fetch the clerk, and made him open the safe. The yield: perhaps $40 ($1,000 today). The leader also took the registered packages from the car’s mail compartment.

The four bandits wore handkerchiefs over their faces, although the face of the leader of the gang was briefly revealed. He was described as “a small, spare man with a moustache and imperial” (an imperial is a pointed beard on the chin. Think Buffalo Bill, General Custer, Cardinal Richelieu.).

As the robbers left the station, they warned those on the platform that if anyone fired at them they would return to burn the station and raise “merry h—l.”

The gang disappeared on foot behind the station but was thought to have had horses hidden nearby.

Passengers on the train were not molested “in the slightest manner,” the Democrat wrote.

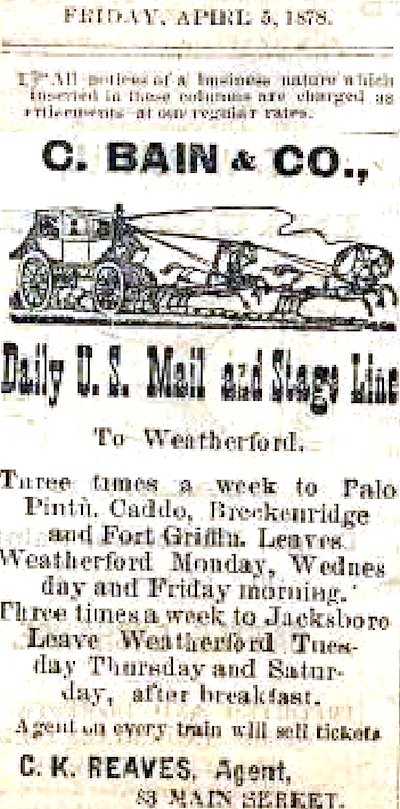

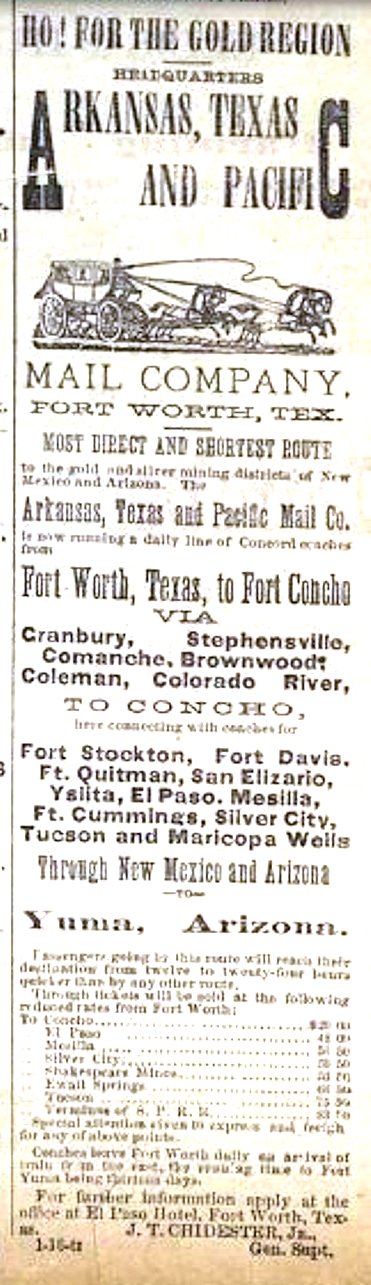

The daily stage to Yuma, Arizona left Fort Worth’s El Paso Hotel upon arrival of the Texas & Pacific passenger train from the east. The trip to Yuma was twelve hundred miles and took thirteen days, thus averaging ninety dusty miles a day. Concord coaches, swaying on a suspension of leather straps, were pulled by four horses.

The daily stage to Yuma, Arizona left Fort Worth’s El Paso Hotel upon arrival of the Texas & Pacific passenger train from the east. The trip to Yuma was twelve hundred miles and took thirteen days, thus averaging ninety dusty miles a day. Concord coaches, swaying on a suspension of leather straps, were pulled by four horses.

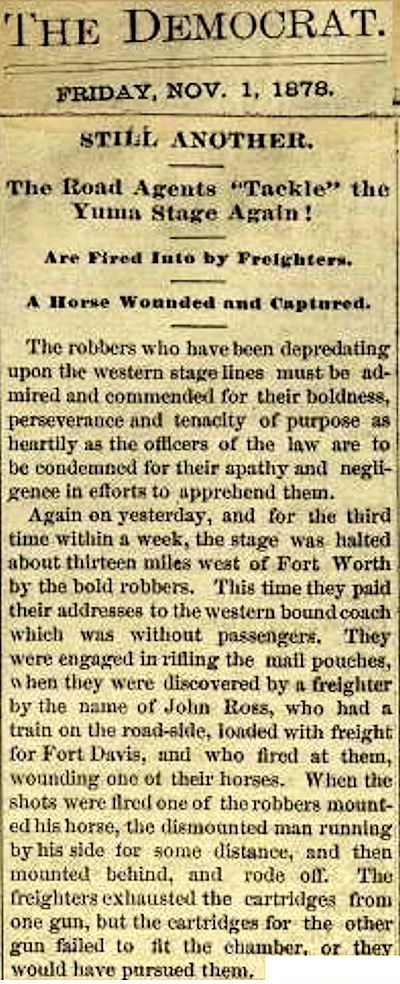

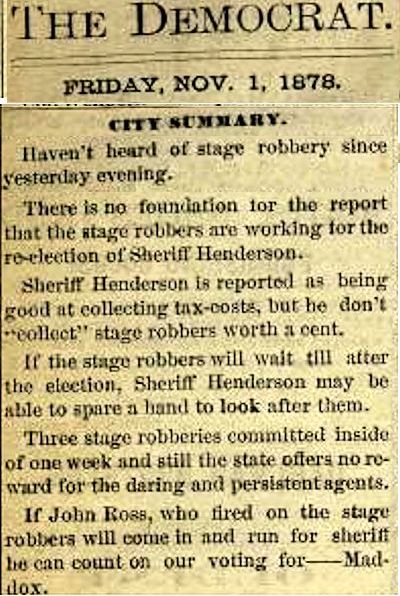

Trains and stagecoaches were favorite targets of robbers in 1878. With each new robbery railroad and stagecoach companies, express companies, and newspaper editors pointed fingers and fretted. After three stagecoach robberies in Tarrant County in one week, the Democrat criticized Sheriff Henderson and the state.

Trains and stagecoaches were favorite targets of robbers in 1878. With each new robbery railroad and stagecoach companies, express companies, and newspaper editors pointed fingers and fretted. After three stagecoach robberies in Tarrant County in one week, the Democrat criticized Sheriff Henderson and the state.

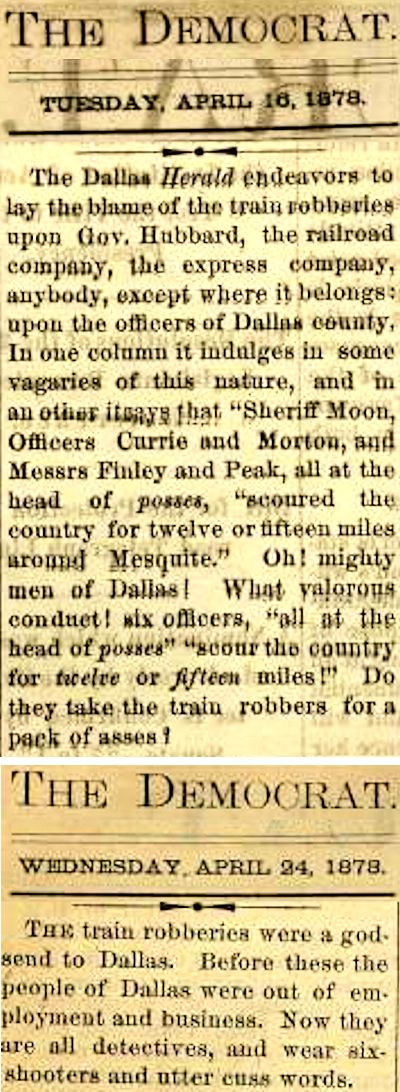

Just as Tarrant County had suffered three stagecoach robberies in a week, the Eagle Ford train robbery was one of four in Dallas County between February 22 and April 10. (According to the book Texas Train Robberies by W. C. Jameson, all four were committed by Sam Bass and colleagues. Bass would be killed on July 21.) That crime spree was all the pretext Paddock’s Democrat needed to take a couple of cat’s-paw swipes at Panther City’s downriver rival.

Posts About Fort Worth’s Wild West History

Posts About Crime Indexed by Decade