Before he drove a luxury automobile, he drove cattle. Before he built hotels, he built herds. Before he sat on a board of directors, he sat on a saddle.

Christopher Augustus O’Keefe was born on the family plantation in Alabama in 1852. He was, the Star-Telegram wrote in 1929, of the third generation of Irish gentry.

Like Cowtown’s other cattleman capitalists—Fountain Goodlet Oxsheer, W. T. Waggoner, Samuel Burk Burnett, Winfield Scott, Marion Sansom, George T. and William D. Reynolds—O’Keefe developed his cowman skills early. When his family relocated in 1865, Gus gained his first experience as a trail hand by helping his brother drive the family’s milk cows to their new home.

At age fifteen Gus left home. He and his older brother James went to Minnesota, where they cut wheat and bound it by hand. They also freighted railroad crossties by sled across a frozen bay of Lake Superior.

Gus then went down the Mississippi River as far as St. Louis and veered west on foot into Texas, arriving in Red River County in 1868.

He drove a team of oxen, he herded cattle to the ports of Shreveport and Jefferson to be shipped to New Orleans.

One day in Louisiana O’Keefe treated himself to luxury travel—a train. The train passed a magnificent herd of horses. O’Keefe was so enchanted by the rolling thunder that he got off the train at the next stop, made his way back to the ranch, and hired himself out to the owner.

By 1878 he had moved on to Mitchell County in west Texas. There he hired on as a cowhand for ranchers George W. Waddell and J. F. Byler.

Soon O’Keefe moved on to work on the Long S Ranch of Christopher Columbus Slaughter. The Long S sprawled across Mitchell and Howard counties. Slaughter, regarded as the “cattle king of Texas,” was the brother of Fort Worth’s John Bunyan Slaughter.

C. C. Slaughter was impressed with O’Keefe as a businessman and a cowman and appointed him ranch manager, a job that allowed O’Keefe to acquire a one-sixth interest in Slaughter’s forty thousand-plus cattle.

In those days some Texas ranches were kingdoms unto themselves, sprawling over tens of thousands, even a million acres. The Texas range was mostly unfenced, although there were occasional “drift fences” to prevent cattle from drifting too far south to escape cold weather in the winter.

Then came the winter of 1884-1885. A cowboy of the Long S Ranch recalled January 1855: “One evening about three o’clock a great black cloud appeared in the north. We knew a blizzard was coming and that a drift [of the cattle] was certain. In less than an hour the storm was raging, but it was nearly midnight before the lead of the herd began to pass. We were on the very center of the line of the drift and the ground was covered with six or seven inches of snow. . . . All night the blizzard raged and all night the mighty avalanche of cattle moved before it.”

Writer Patrick Dearen writes that the blizzard swept the Plains from the northeast. Cattle instinctively fled the snow and bitter northeast wind, migrating southwestward. They drifted out of Kansas and Colorado, Oklahoma, and the Texas Panhandle by the tens of thousands, straying as much as six hundred miles from their home range.

When these herds struck an occasional drift fence, the lead cattle stopped and simply froze to death. Tens of thousands died and piled up along the fences. The carcasses created a macabre staircase by which trailing cattle crossed the obstacle.

Tens of thousands of cattle drifted to the Pecos River of west Texas, where they massed for miles along the sheer bank.

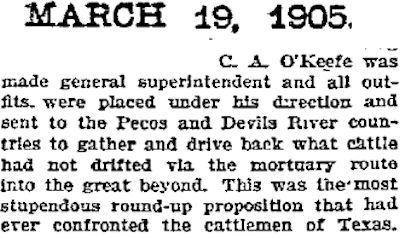

Dearen writes that in late winter 1885 Texas ranchers, with their losses mounting by the day, convened in Colorado City in Mitchell County and appointed Gus O’Keefe to organize a roundup the likes of which had never been attempted.

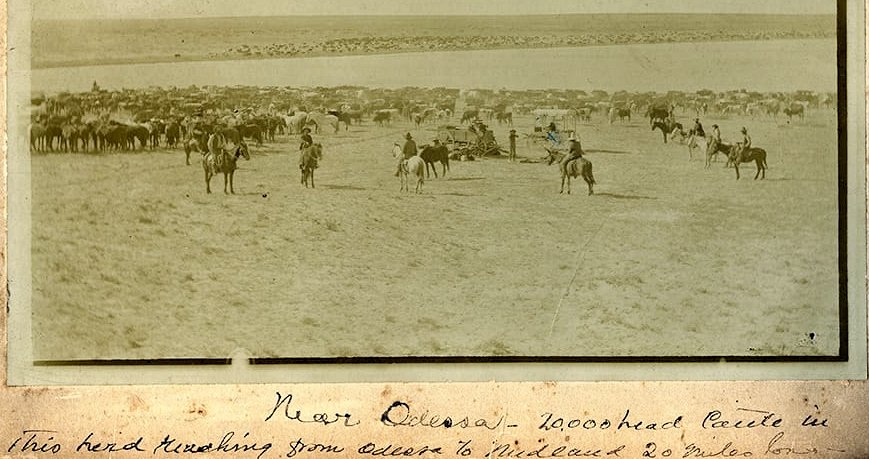

O’Keefe set up his headquarters in Odessa and dispatched more than two hundred cowboys and one thousand saddle horses to the Pecos River area to round up the stranded cattle.

A rare photo of the Pecos Drift roundup shows part of a herd twenty miles long and containing twenty thousand cattle. One eyewitness recalled seeing a swath of cattle three miles wide that required fourteen hours to pass a given point. (Photo from the Haley Memorial Library of Midland.)

A rare photo of the Pecos Drift roundup shows part of a herd twenty miles long and containing twenty thousand cattle. One eyewitness recalled seeing a swath of cattle three miles wide that required fourteen hours to pass a given point. (Photo from the Haley Memorial Library of Midland.)

The roundup would last two months and take its tolls on cows and cowboys alike. An estimated 150,000 cattle had died in the Pecos Drift. But under O’Keefe’s supervision an equal number were returned to ranches.

With the Pecos Drift roundup Gus O’Keefe had ensured that his name would be remembered for decades in the cattle industry of the Southwest.

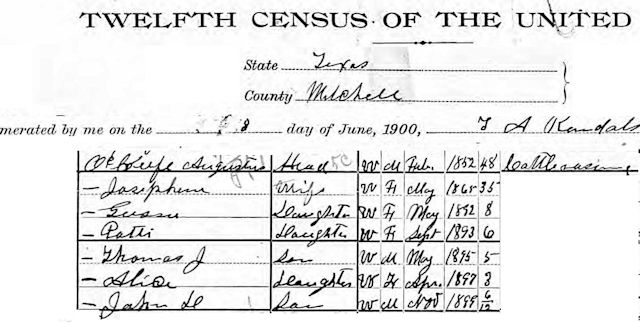

In 1888 he left the Slaughter operation and bought the C A Ranch near Colorado City. Three years later he married Josephine McMillon. They would have five children.

He also bought the HXW Ranch. In the 1890s O’Keefe sold the C A and the HXW and bought the Fish Ranch in Dawson County. The ranch’s brand was the outline of a fish. He eventually would own tens of thousands of acres of ranchland.

O’Keefe also was director of Colorado City National Bank and remained the biggest taxpayer in Mitchell County, B. B. Paddock wrote.

O’Keefe also was director of Colorado City National Bank and remained the biggest taxpayer in Mitchell County, B. B. Paddock wrote.

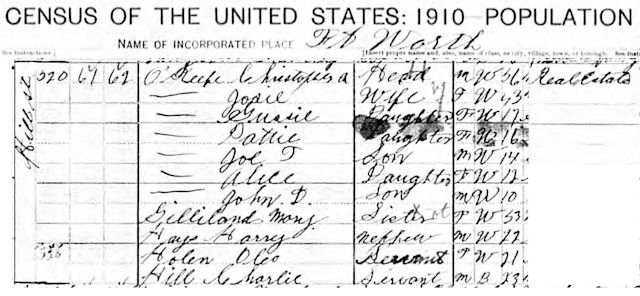

By 1905 cattle had made Gus O’Keefe a wealthy man. That year he moved to Fort Worth so that his children could attend better schools. He bought the Quality Hill mansion that L. B. Weinman had designed in 1897 for cattleman William T. Scott.

By 1905 cattle had made Gus O’Keefe a wealthy man. That year he moved to Fort Worth so that his children could attend better schools. He bought the Quality Hill mansion that L. B. Weinman had designed in 1897 for cattleman William T. Scott.

But by 1905 O’Keefe was fifty-three years old. Many of those years had been hard ones riding the range. He suffered poor health the rest of his life.

Nonetheless, in Fort Worth O’Keefe added real estate and oil production to his portfolio. In the 1910 census he listed his occupation as real estate. (Hill Street was renamed “Summit.”)

Nonetheless, in Fort Worth O’Keefe added real estate and oil production to his portfolio. In the 1910 census he listed his occupation as real estate. (Hill Street was renamed “Summit.”)

In 1916 O’Keefe and W. J. Binyon Sr. and Jr. chartered Binyon-O’Keefe Fire Proof Storage Company. The building still stands.

In 1916 O’Keefe and W. J. Binyon Sr. and Jr. chartered Binyon-O’Keefe Fire Proof Storage Company. The building still stands.

O’Keefe owned prime real estate on Main and Houston streets downtown. On one of his blocks stands the most prominent legacy of C. A. O’Keefe: his Blackstone Hotel.

O’Keefe owned prime real estate on Main and Houston streets downtown. On one of his blocks stands the most prominent legacy of C. A. O’Keefe: his Blackstone Hotel.

The hotel opened on October 10, 1929, two weeks before the stock market crash.

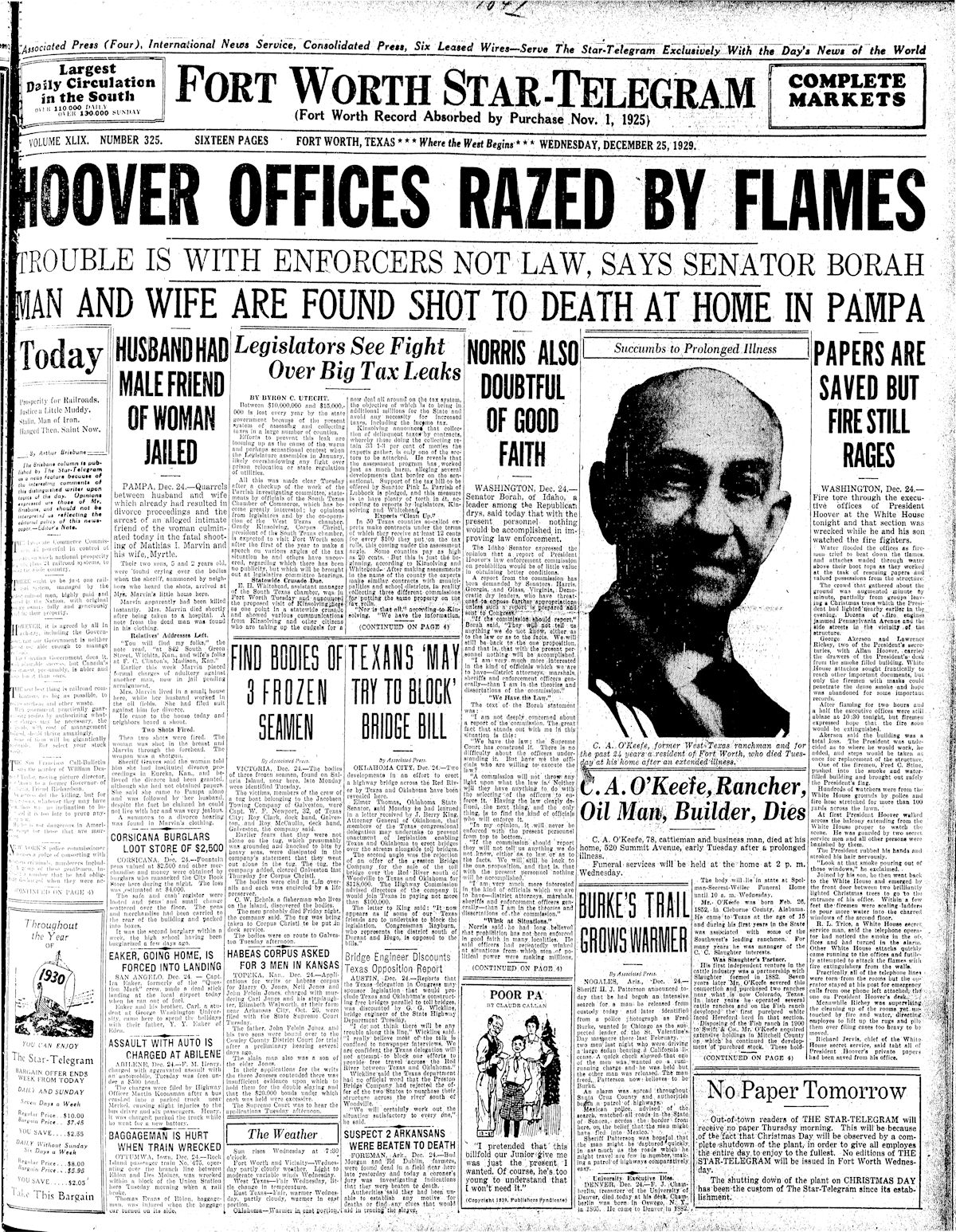

Christopher Augustus O’Keefe, ramrod of the Pecos Drift roundup and cattleman capitalist, died on Christmas Eve 1929, ten weeks after his Blackstone Hotel opened. He was seventy-seven years old.

Christopher Augustus O’Keefe, ramrod of the Pecos Drift roundup and cattleman capitalist, died on Christmas Eve 1929, ten weeks after his Blackstone Hotel opened. He was seventy-seven years old.

Among his honorary pallbearers were Star-Telegram publisher Amon Carter, cattleman capitalists William E. Connell and Cass Edwards, and cattlemen from around the state.

Gus O’Keefe is buried in Shannon Rose Hill Cemetery.

Gus O’Keefe is buried in Shannon Rose Hill Cemetery.