He was a mover and a shaker, a “yes, we can”er and a canner.

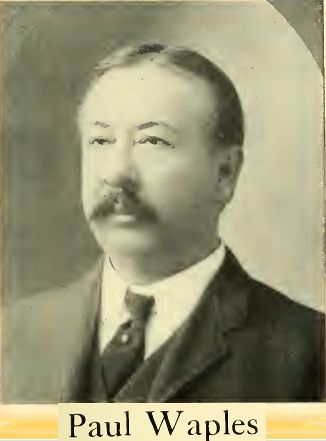

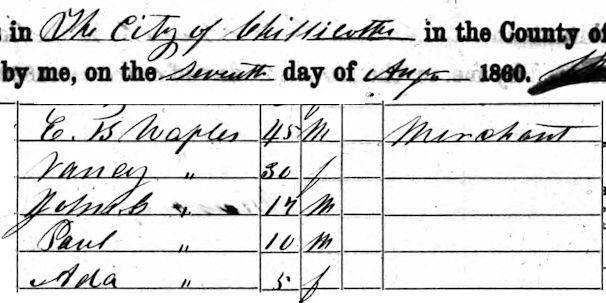

Paul Waples was born in Chillicothe, Missouri in 1850. By 1872 he had graduated from college and married in that state.

Paul Waples was born in Chillicothe, Missouri in 1850. By 1872 he had graduated from college and married in that state.

Meanwhile that same year, five hundred miles south of Chillicothe, the Missouri-Kansas-Texas (Katy) railroad was laying track south through Oklahoma toward Texas.

Sam Hanna and Joe Owens operated a commissary at Colbert’s Ferry, a crossing on the Red River near where the Katy track would cross the river into Grayson County. The commissary sold such staples as coffee beans, crackers, sugar, and lard to railroad workers and ranchers and ammunition to hunters.

When the railroad reached Grayson County in 1872 a town site was laid out along the tracks, and town lots were sold. The town of Denison was born. (Denison was named for the vice president of the railroad.)

Hanna and Owens relocated to the new town.

They weren’t the only ones.

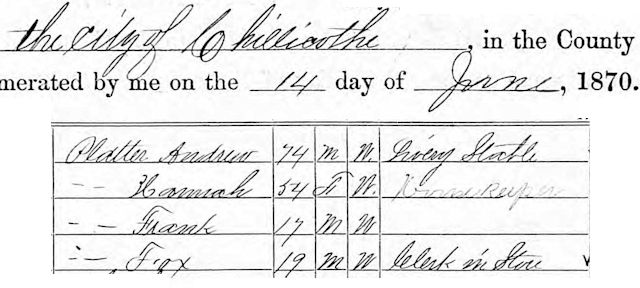

Back in Chillicothe, Missouri several families, including Leeper, Lingo, Waples, and Platter, moved to the Sherman-Denison area in the 1870s.

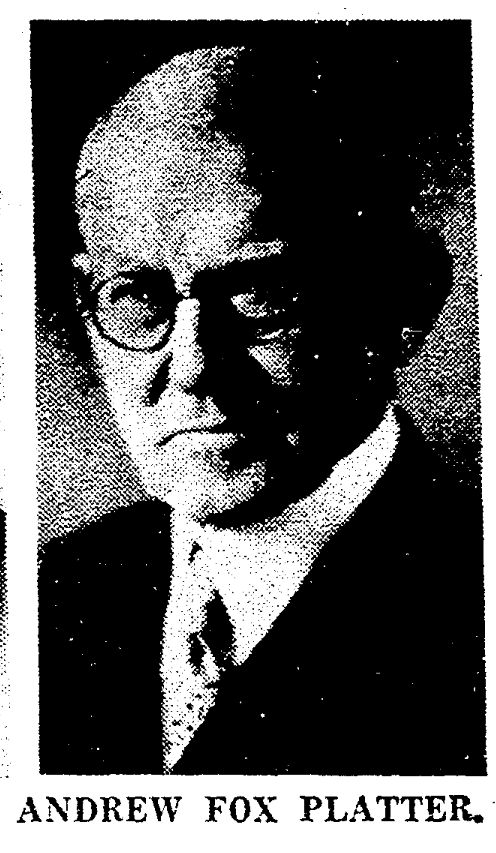

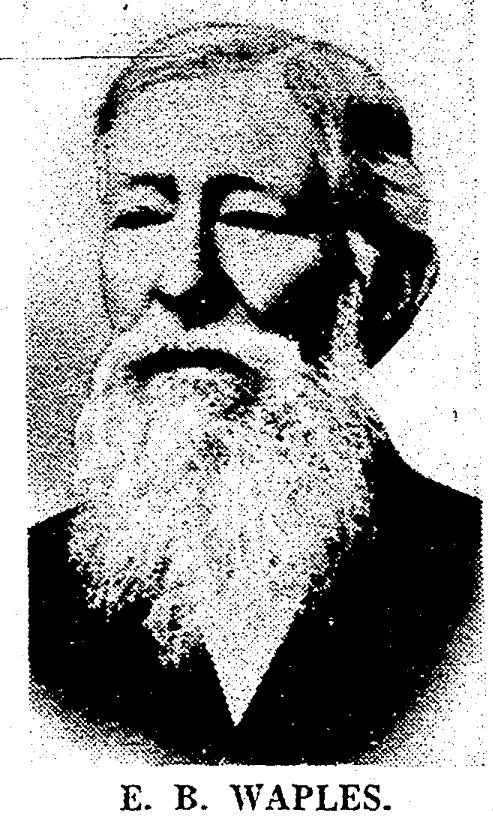

In 1878 one of the Platters—Andrew Fox Platter—became a bookkeeper for the Hanna-Owens firm. In 1882 Platter bought Owens’s interest, and the firm became Hanna-Platter & Company. That same year Fox Platter married Fannie Waples, daughter of Sherman merchant Edward B. Waples.

In 1878 one of the Platters—Andrew Fox Platter—became a bookkeeper for the Hanna-Owens firm. In 1882 Platter bought Owens’s interest, and the firm became Hanna-Platter & Company. That same year Fox Platter married Fannie Waples, daughter of Sherman merchant Edward B. Waples.

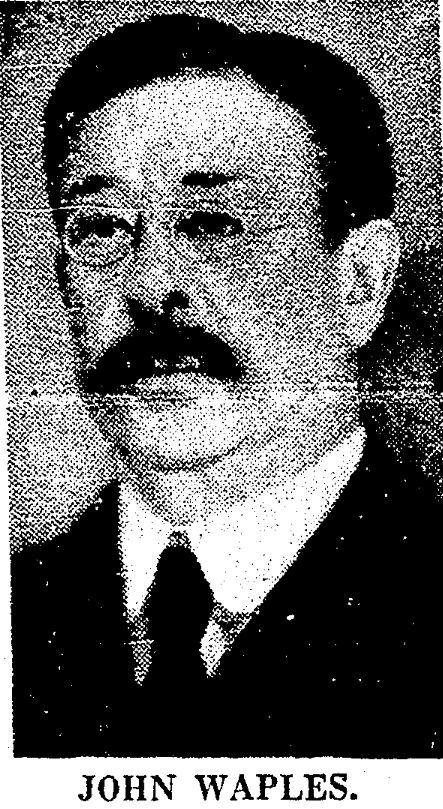

In 1885 Platter convinced his father-in-law, Edward B. Waples, and two brothers-in-law, Paul and John Graves Waples, to join his company. The elder Waples bought interest in the company and was named president.

In 1885 Platter convinced his father-in-law, Edward B. Waples, and two brothers-in-law, Paul and John Graves Waples, to join his company. The elder Waples bought interest in the company and was named president.

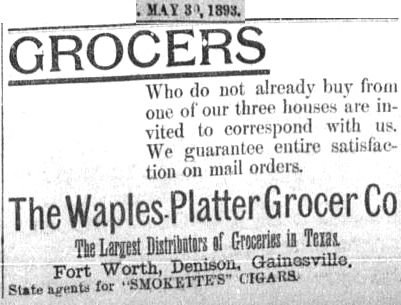

In 1887 the company was renamed “Waples-Platter & Company.”

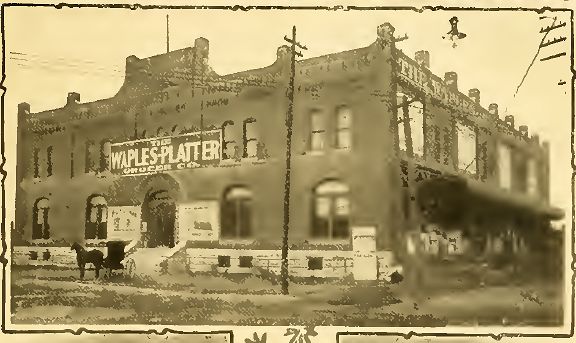

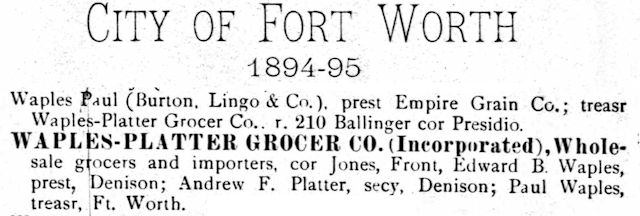

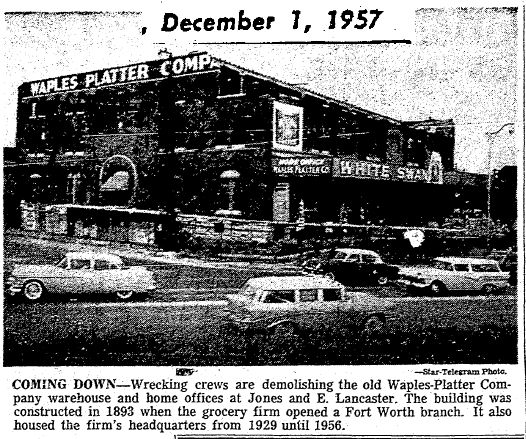

Waples-Platter wholesale grocery company opened a branch in Fort Worth in 1893.

Waples-Platter wholesale grocery company opened a branch in Fort Worth in 1893.

The building was located at Jones and Lancaster streets.

The building was located at Jones and Lancaster streets.

In 1894 Paul Waples moved to Fort Worth. He was treasurer of Waples-Platter and president of Empire Grain Company. He lived on Ballinger Street on Quality Hill.

In 1894 Paul Waples moved to Fort Worth. He was treasurer of Waples-Platter and president of Empire Grain Company. He lived on Ballinger Street on Quality Hill.

With the death of Edward B. Waples in 1898 Paul became president of Waples-Platter.

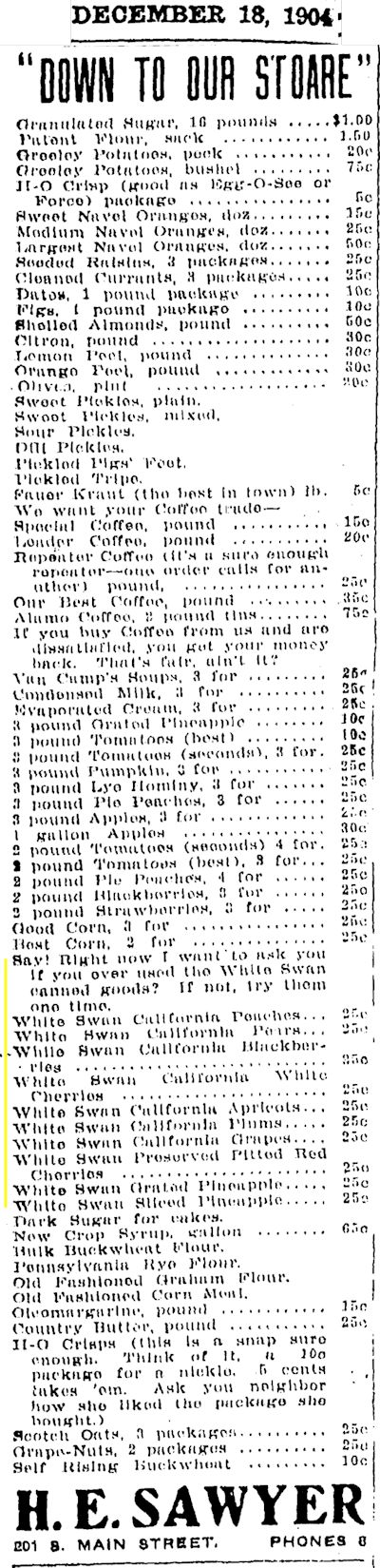

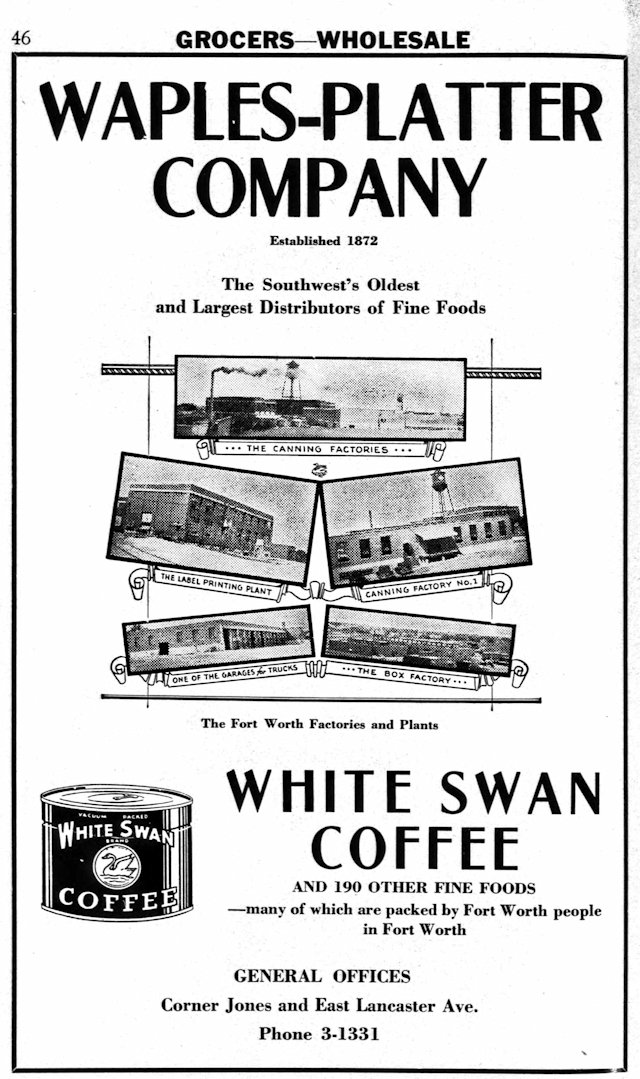

Waples-Platter distributed its White Swan brand canned foods and coffee to grocers such as Turner & Dingee and Henry Sawyer at 201 South Main Street.

Waples-Platter distributed its White Swan brand canned foods and coffee to grocers such as Turner & Dingee and Henry Sawyer at 201 South Main Street.

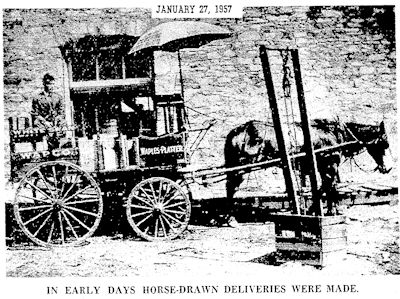

Deliveries to grocers were made by horse and wagon. There was a stable adjacent to the headquarters and warehouse on Jones Street. Not until 1917 would Waples-Platter convert from horses to trucks.

Deliveries to grocers were made by horse and wagon. There was a stable adjacent to the headquarters and warehouse on Jones Street. Not until 1917 would Waples-Platter convert from horses to trucks.

The year 1902 was a big one for Fort Worth. By then Paul Waples had become a civic leader. He was president of the Board of Trade (forerunner of the chamber of commerce) and in that capacity took part in laying the cornerstone for the Swift and Armour packing plants on March 12. People in the photo identified with numbers written above their heads: 1. Board of Trade vice president Dr. J. L. Cooper, 2. Paul Waples, 3. unidentified, 4. alderman Tom Murray, 5. alderman B. L. Waggoman, 6. Police Chief William Rea, 7. city waterworks superintendent Hugh L. Calhoun, 8. banker W. G. Newby, 9. cattleman and planter Van Zandt Jarvis, 10. civic leader J. J. Jarvis. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

The year 1902 was a big one for Fort Worth. By then Paul Waples had become a civic leader. He was president of the Board of Trade (forerunner of the chamber of commerce) and in that capacity took part in laying the cornerstone for the Swift and Armour packing plants on March 12. People in the photo identified with numbers written above their heads: 1. Board of Trade vice president Dr. J. L. Cooper, 2. Paul Waples, 3. unidentified, 4. alderman Tom Murray, 5. alderman B. L. Waggoman, 6. Police Chief William Rea, 7. city waterworks superintendent Hugh L. Calhoun, 8. banker W. G. Newby, 9. cattleman and planter Van Zandt Jarvis, 10. civic leader J. J. Jarvis. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

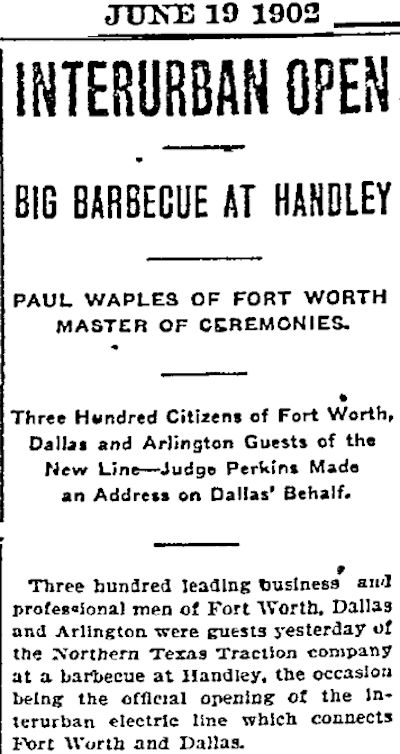

And in June Waples was master of ceremonies at the formal opening of the interurban at the Lake Erie power plant.

And in June Waples was master of ceremonies at the formal opening of the interurban at the Lake Erie power plant.

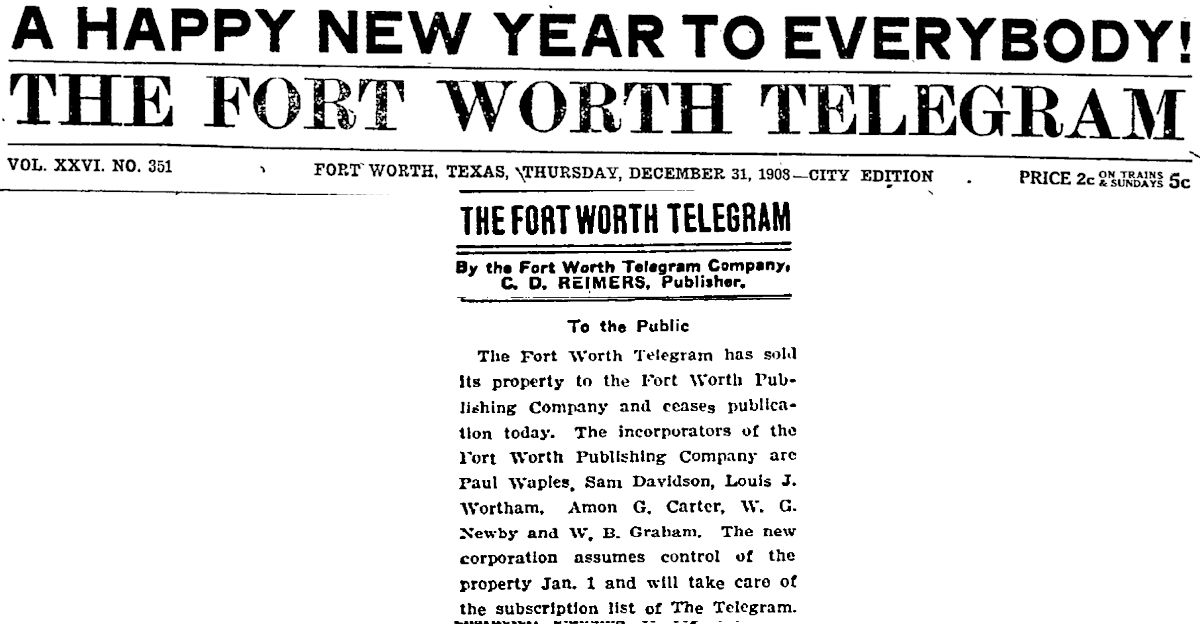

Fast-forward to 1905. Amon Giles Carter had landed in Fort Worth from Bowie via San Francisco. Carter wanted to publish a newspaper to compete with Fort Worth’s Telegram. Carter had no money to invest in the newspaper, but he knew someone who did: Paul Waples. Carter talked Waples into investing in the venture. As the major money man, Waples became president of the new publishing company.

The Star published its first edition on February 1, 1906. But despite ad manager Carter’s flair for selling ads, the Star soon was losing money. All the local advertising went to the rival Telegram, leaving the Star with national ads for patent medicines. Bankruptcy loomed. Then Carter came up with an audacious plan: Rather than fold, up the ante. Carter sold Paul Waples on investing still more money.

And they bought the Telegram.

Waples was an incorporator of the new company.

Waples was an incorporator of the new company.

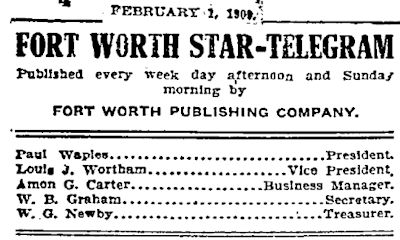

And when the Star and Telegram merged as the Star-Telegram, Waples remained as president.

And when the Star and Telegram merged as the Star-Telegram, Waples remained as president.

In 1912 Waples-Platter bought twenty-seven acres just west of the Cobb brothers’ North Glenwood addition and built a cannery in 1913.

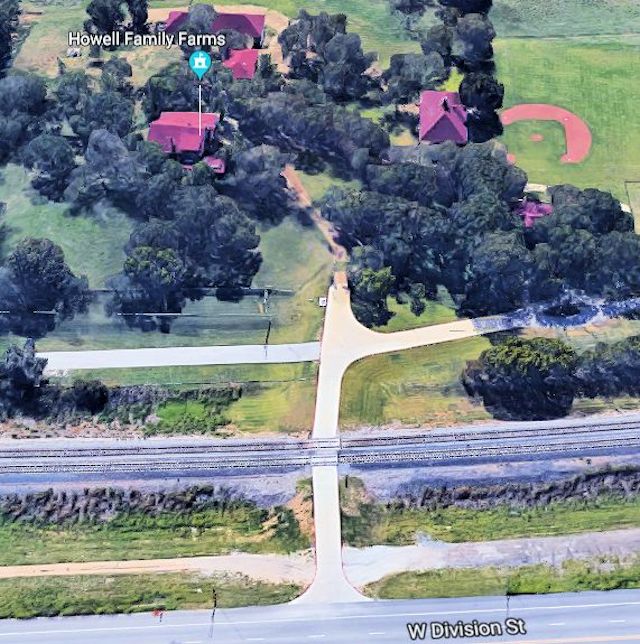

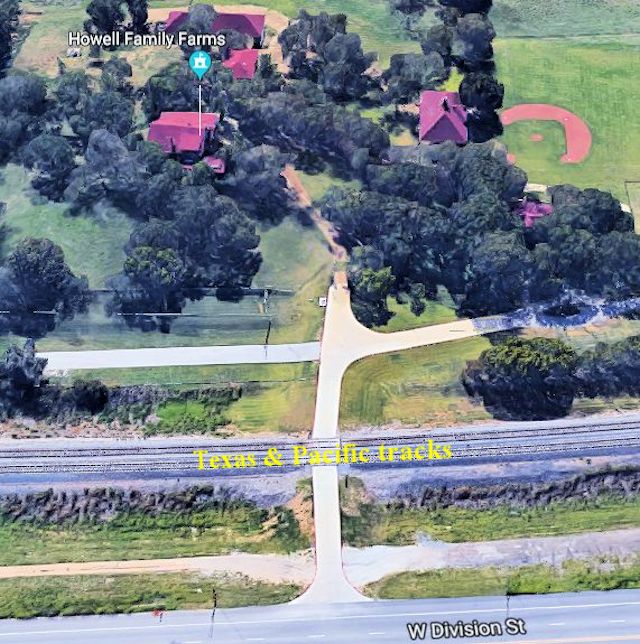

Also in 1912 Paul Waples bought 622 rural acres on a wooded hillside east of Handley. The north edge of the property bordered the narrow traffic corridor that included the Fort Worth-Dallas Pike, the Texas & Pacific tracks, and the interurban track. The property was 2.5 miles east of the interurban power plant where Waples had served as master of ceremonies when the interurban opened in 1902.

At the highest point on the property he built a three-story brick home and an eleven-stall barn. At the bottom of the hill the iron entry gate bore the monogram W. On his country estate he walked with his dog, Prince Hamlet, and rode his horses.

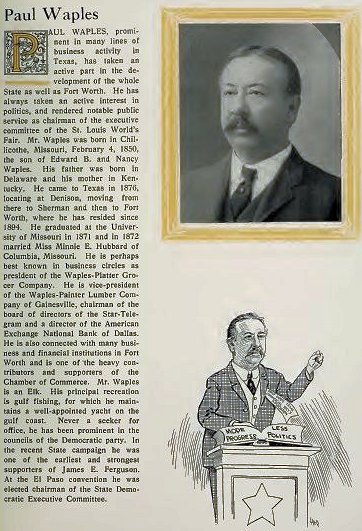

In 1914 Paul Waples had lived in Fort Worth twenty years and was one of Fort Worth’s established civic leaders. That year he was included in the book Makers of Fort Worth.

In 1914 Paul Waples had lived in Fort Worth twenty years and was one of Fort Worth’s established civic leaders. That year he was included in the book Makers of Fort Worth.

As a civic booster with “yes, we can” optimism, Waples rivaled B. B. Paddock and Amon Carter. Waples was a widower and childless, and he seemed to channel his attention into the growth of his adopted hometown. Of course, the growth of Fort Worth also made men such as Paddock, Carter, and Waples wealthy.

By 1916 Paul Waples was director of three banks, chairman of the Democratic state executive committee, a supporter of the Union Gospel Mission and the YMCA, owned interests in lumber companies and the coal mine at Thurber, was a trustee of Texas A&M University. He had helped to persuade Swift and Armour to build in Fort Worth in 1902 and Chevrolet in 1916.

He had been chairman of the executive committee of the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair.

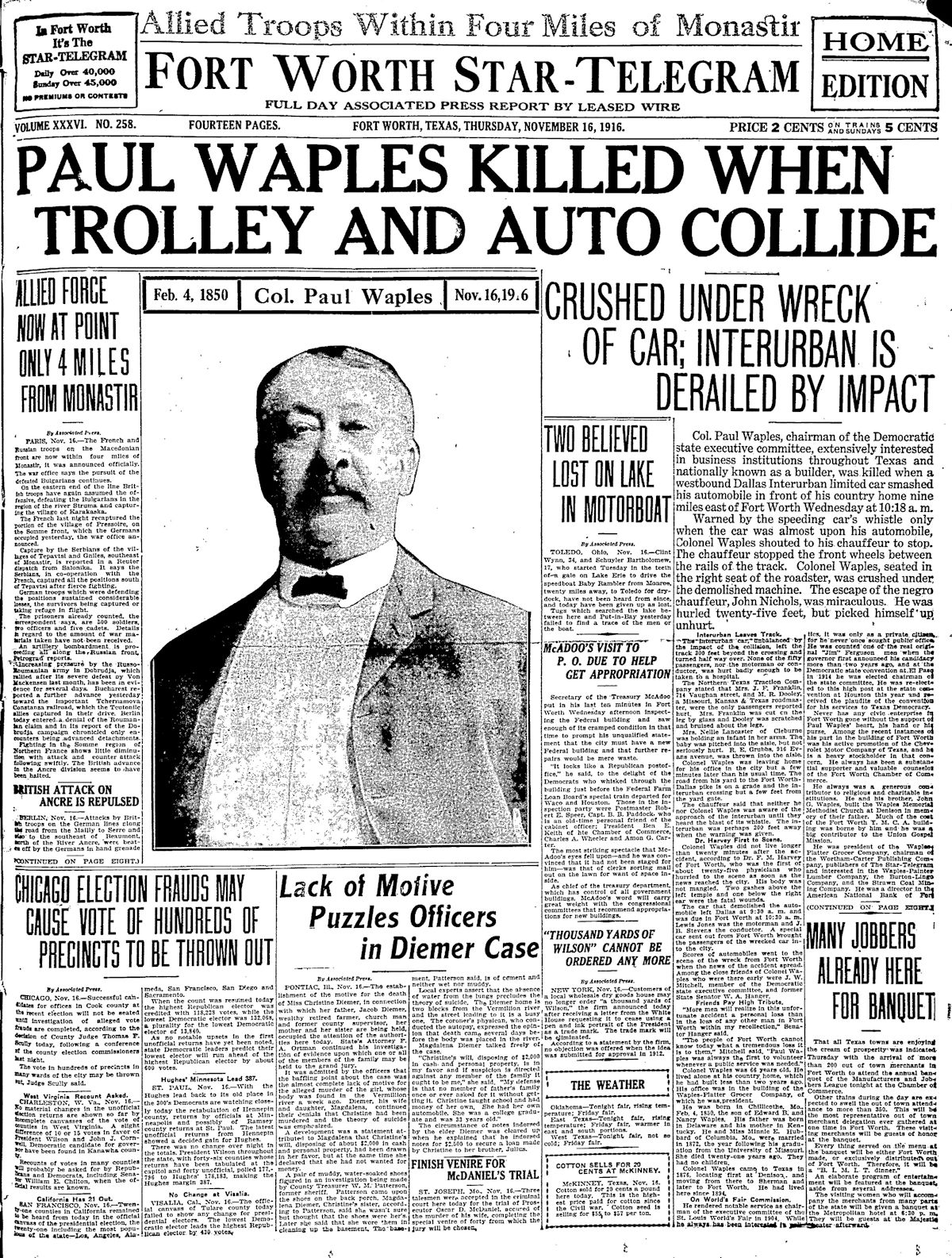

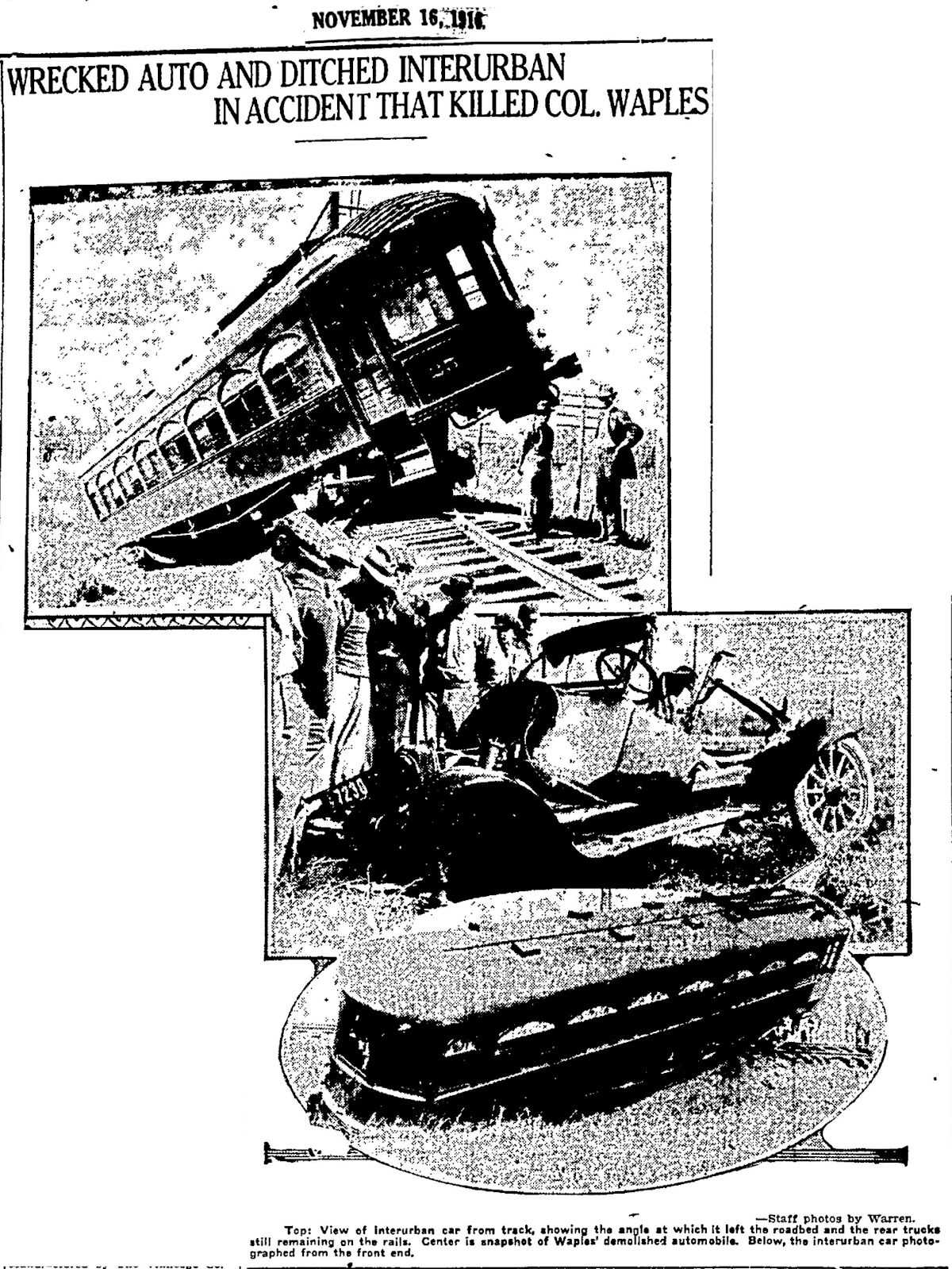

On the morning of November 15, 1916 Paul Waples was sitting in the back seat of his car as his chauffeur drove down the drive of his estate toward the Fort Worth-Dallas Pike en route to Waples’s office in Fort Worth.

To get to the pike, the car had to cross both the railroad tracks and the interurban track.

At 10:18 the westbound interurban trolley was traveling at sixty miles per hour in open country as it neared the Waples crossing.

The Star-Telegram later wrote that Waples and his chauffeur did not see the trolley and hear the “blast of its whistle” until the trolley was just two hundred feet away. Traveling at sixty miles per hour, the trolley covered those two hundred feet in a heartbeat.

(As I understand it, interurban motormen sounded a bell as an alarm in the city but a whistle in rural areas.)

Waples told his chauffeur to stop their car. The driver stopped, but the front wheels of the car were on the track.

The trolley car rammed the right front side of the Waples car.

The chauffeur was thrown twenty-five feet from the car but not seriously injured.

The trolley car was a motorcar, meaning it was self-contained: It could both carry passengers and pull a trailer (motorless) car.

After ramming the Waples car, the trolley car careened along the track for three hundred feet before partially derailing and coming to rest on the embankment of the track’s elevated roadbed.

The trolley car had downed some telephone poles. The interurban’s overhead line also was downed, posing an electrical hazard.

Twenty-five physicians rushed to the scene from Fort Worth, but none of the fifty passengers was seriously injured.

But Paul Waples, age sixty-six, lived only twenty minutes after the accident. (Fort Worth historian Andy Nold points out that the motorcar was no. 25, which has been restored and is on display at Fort Worth Central Station downtown.)

But Paul Waples, age sixty-six, lived only twenty minutes after the accident. (Fort Worth historian Andy Nold points out that the motorcar was no. 25, which has been restored and is on display at Fort Worth Central Station downtown.)

Passengers praised the courage of the motorman, Lewis Jones, who stayed at the controls, blowing his whistle and braking to stop the trolley as quickly as he safely could.

One passenger said: “When the impact came and the interurban jumped the track he never flinched, sticking right to his post with glass flying all about him and blood streaming from his face.”

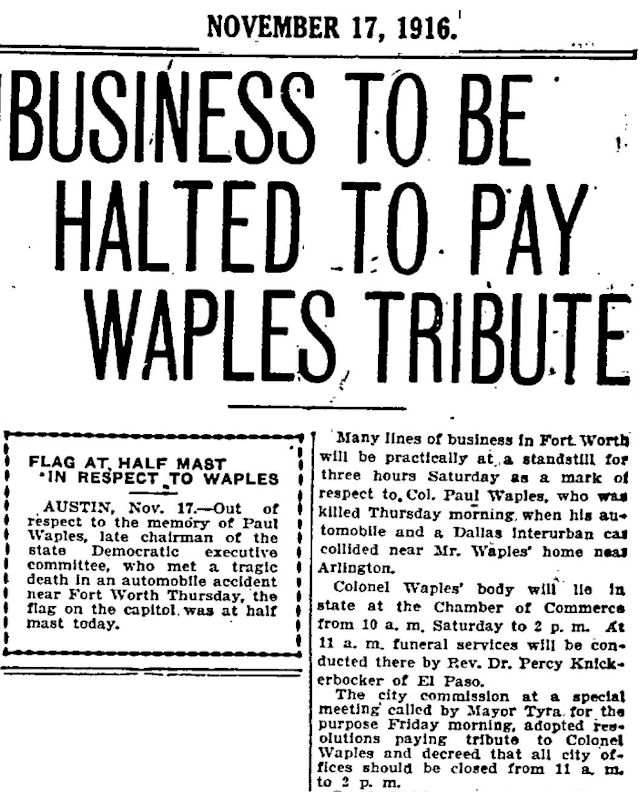

On November 17 Fort Worth municipal offices closed for three hours while Waples’s body lay in state in the chamber of commerce auditorium. All wholesale grocery companies in town also closed. In Austin the flag atop the Capitol was lowered to half staff.

On November 17 Fort Worth municipal offices closed for three hours while Waples’s body lay in state in the chamber of commerce auditorium. All wholesale grocery companies in town also closed. In Austin the flag atop the Capitol was lowered to half staff.

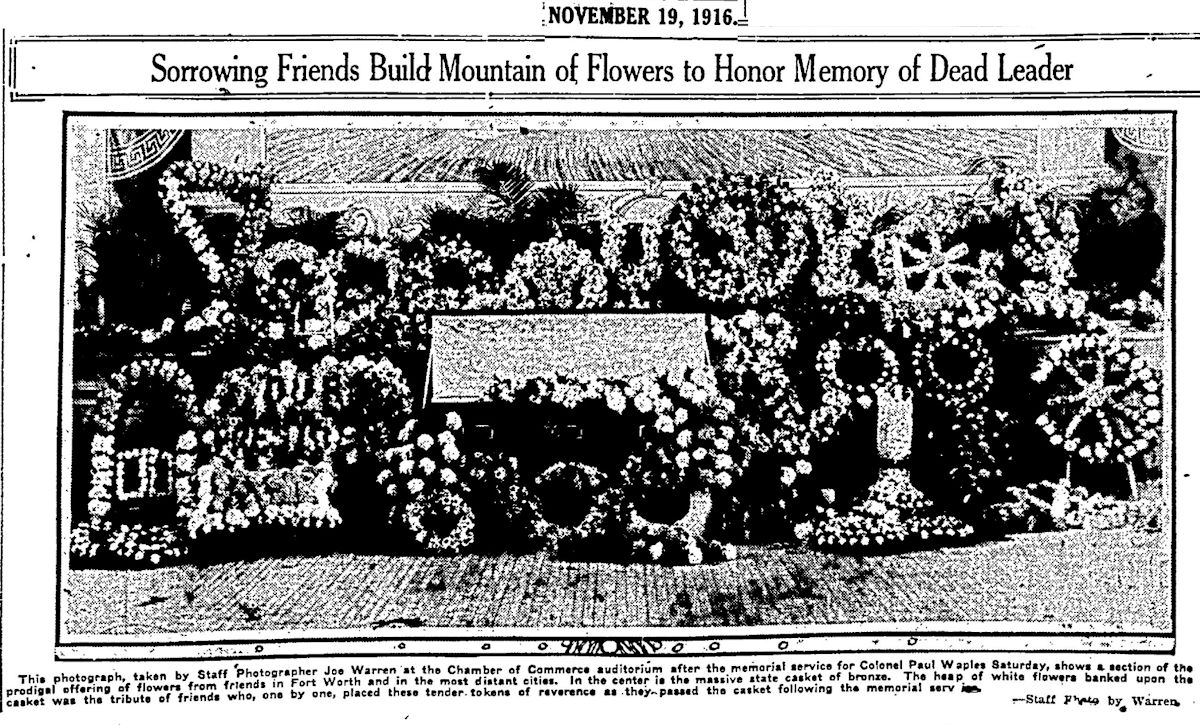

Fifteen hundred people, among them Governor James Ferguson, attended a memorial service in the chamber of commerce auditorium. After lying in state in the auditorium, the body was taken back to Waples’s country estate to lie in state until the train trip to Denison for funeral and burial.

Fifteen hundred people, among them Governor James Ferguson, attended a memorial service in the chamber of commerce auditorium. After lying in state in the auditorium, the body was taken back to Waples’s country estate to lie in state until the train trip to Denison for funeral and burial.

Photo shows Waples’s casket surrounded by wreaths in the auditorium on November 18.

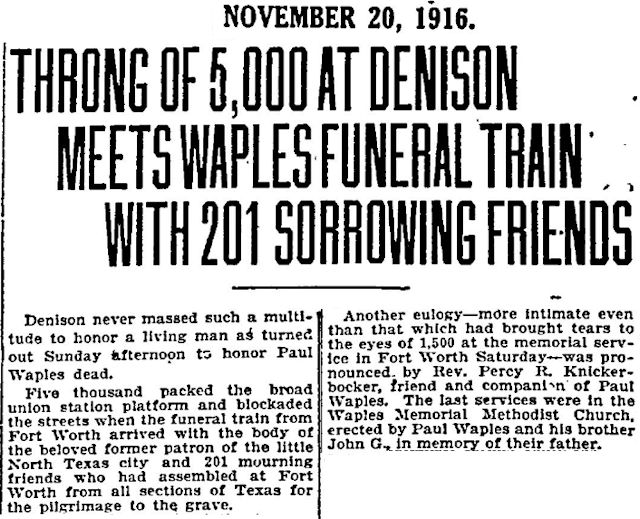

In Denison five thousand people met the train carrying Waples’s body. The body was accompanied by two hundred mourners from Fort Worth. The funeral was held in the church that Paul and John Waples had erected in memory of their father. Active pallbearers included candy maker John P. King and grocer A. S. Dingee. Honorary pallbearers included Paddock, Carter, Governor Ferguson, William P. Hobby Sr., and Samuel Burk Burnett.

In Denison five thousand people met the train carrying Waples’s body. The body was accompanied by two hundred mourners from Fort Worth. The funeral was held in the church that Paul and John Waples had erected in memory of their father. Active pallbearers included candy maker John P. King and grocer A. S. Dingee. Honorary pallbearers included Paddock, Carter, Governor Ferguson, William P. Hobby Sr., and Samuel Burk Burnett.

Paul Waples was buried in Fairview Cemetery in Denison.

Paul Waples was buried in Fairview Cemetery in Denison.

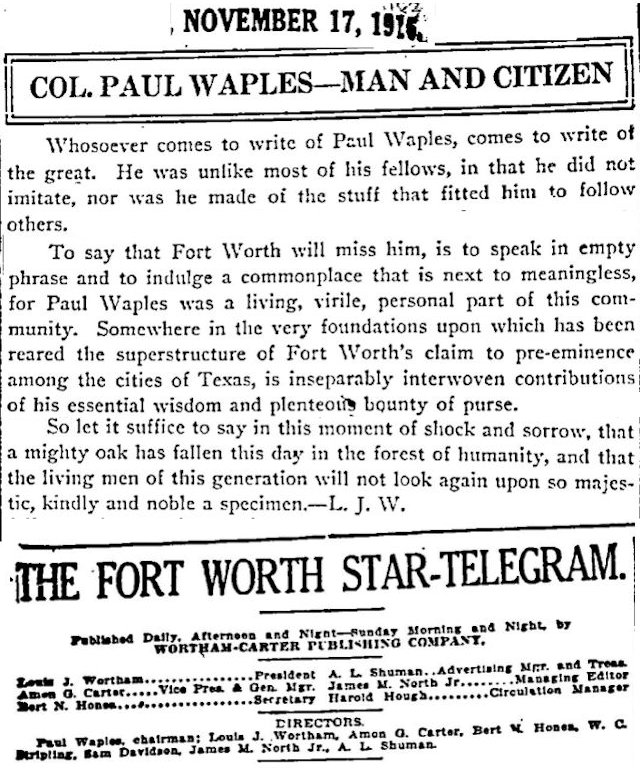

Here is a condensed version of the tribute paid by Louis J. Wortham, Texas legislator and president of the Star-Telegram’s parent, Wortham-Carter Publishing Company.

Here is a condensed version of the tribute paid by Louis J. Wortham, Texas legislator and president of the Star-Telegram’s parent, Wortham-Carter Publishing Company.

“A mighty oak has fallen this day in the forest of humanity,” Wortham wrote.

Waples had remained chairman of the Wortham-Carter Publishing Company board until his death. A plaque at the 1921 Star-Telegram building read: “In grateful remembrance of Colonel Paul Waples, whose unstinted support made possible this enterprise.”

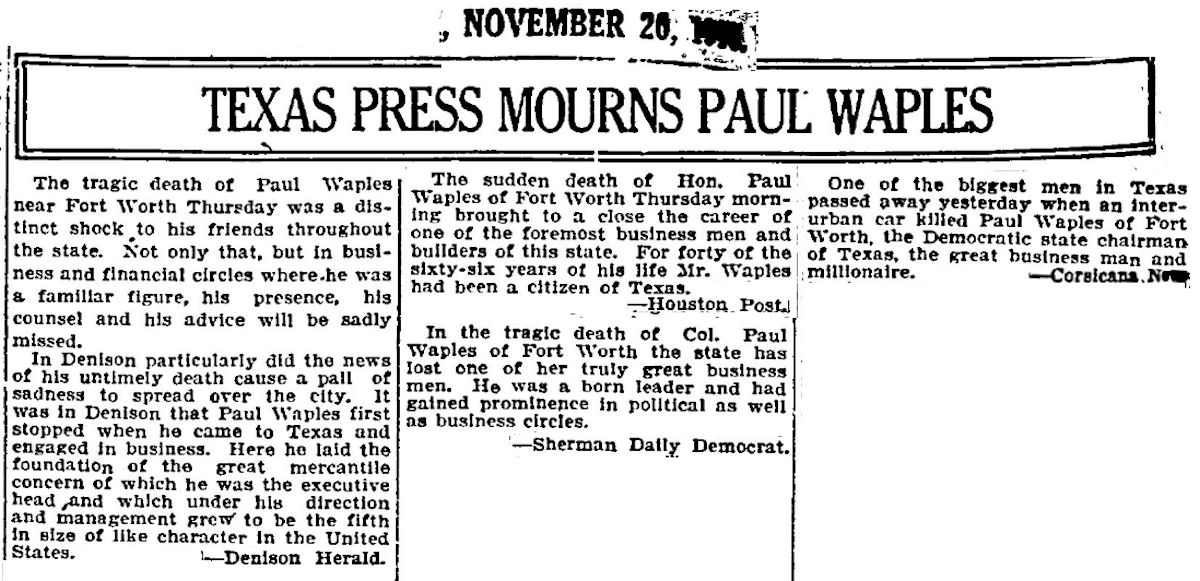

On November 20 the Star-Telegram printed some tributes from other Texas newspapers.

On November 20 the Star-Telegram printed some tributes from other Texas newspapers.

Waples was known for his generosity in addition to his business sense. The Reverend Perry R. Knickerbocker in his eulogy said, “I know of one man who called upon Paul Waples no less than 100 times to get financial aid—always for someone else—and he never failed to get more than he asked for.”

Waples’s will bequeathed $1,000 ($23,000 today) to each of an estimated 170 female employees who had worked for him at least two years.

The value of his estate was estimated at $500,000 ($11.6 million today).

For the company that Paul Waples headed, life and business went on. This ad appeared in the camp publication of Camp Bowie in 1917.

For the company that Paul Waples headed, life and business went on. This ad appeared in the camp publication of Camp Bowie in 1917.

This aerial photo shows the south end of downtown in 1928. The Waples-Platter building is in the lower right. Also shown are the 1899 Texas & Pacific passenger depot, the 1886 Joseph H. Brown building, the Carpenter paper company building, and the 1925 Monnig warehouse (Water Gardens Place today).

This aerial photo shows the south end of downtown in 1928. The Waples-Platter building is in the lower right. Also shown are the 1899 Texas & Pacific passenger depot, the 1886 Joseph H. Brown building, the Carpenter paper company building, and the 1925 Monnig warehouse (Water Gardens Place today).

In 1929 the Waples-Platter company moved its home office from Denison to Fort Worth.

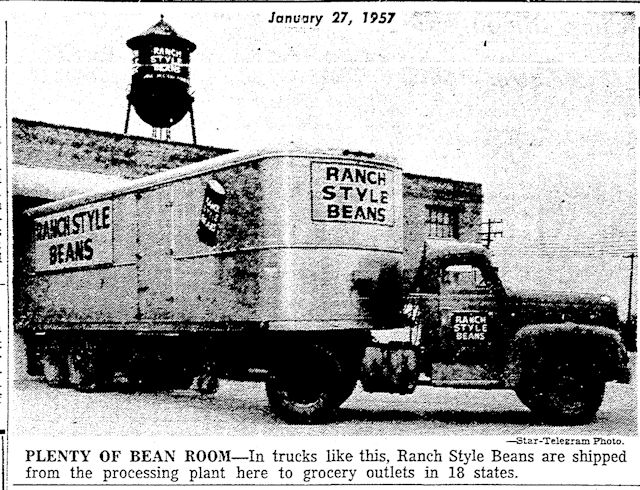

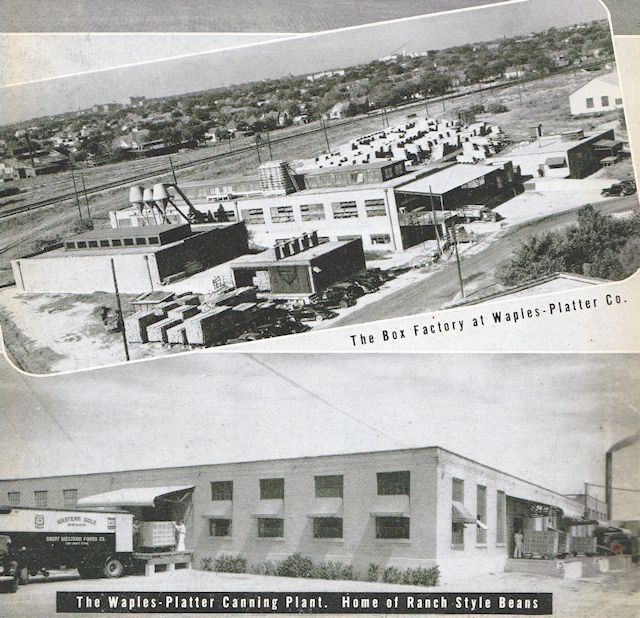

A Waples-Platter subsidiary, Great Western Canning Plant, began canning Chuck Wagon Beans in 1931. But in 1935, because of a trademark conflict, the name of the product was changed to a brand that even our generation remembers: Ranch Style Beans.

A Waples-Platter subsidiary, Great Western Canning Plant, began canning Chuck Wagon Beans in 1931. But in 1935, because of a trademark conflict, the name of the product was changed to a brand that even our generation remembers: Ranch Style Beans.

The seven-story-tall “bean cooker” of the Waples-Platter canning plant was a landmark for years.

This 1942 ad features the 1913 canning plant.

This 1942 ad features the 1913 canning plant.

The facility was served by a spur of the Texas & Pacific railroad and made its own boxes, printed its own labels.

The facility was served by a spur of the Texas & Pacific railroad and made its own boxes, printed its own labels.

This aerial photo from 1949 shows the Waples-Platter canning plant in addition to the fading footprint of the I&GN railyard, Hub furniture factory, city bus barn, Vickery Boulevard, East Lancaster Avenue, and one house of the Cobb brothers’ North Glenwood addition. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

In 1957 the 1893 Waples-Platter building on Jones Street was torn down to make way for the elevated section of I-30.

In 1957 the 1893 Waples-Platter building on Jones Street was torn down to make way for the elevated section of I-30.

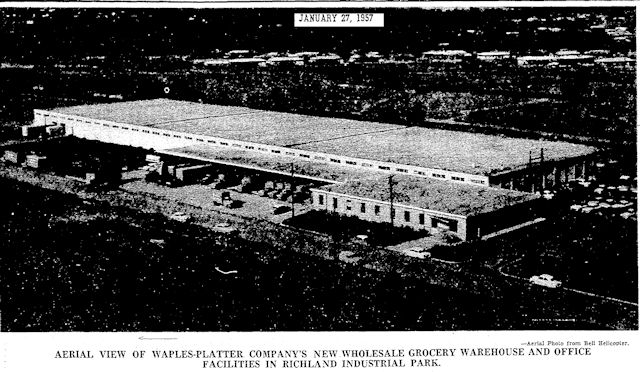

That same year Waples-Platter moved to a new facility in Richland Industrial Park along the Rock Island railroad track. By then the company had become one of the largest grocery wholesalers in the Southwest with twenty-two branches.

That same year Waples-Platter moved to a new facility in Richland Industrial Park along the Rock Island railroad track. By then the company had become one of the largest grocery wholesalers in the Southwest with twenty-two branches.

(If you’re a bean counter, by 1957 the Great Western division of Waples-Platter processed five million pounds of dry beans per year.)

While researching this post I realized that every Saturday for the last two years I have biked past the 1957 Waples-Platter facility at 7133 Burns Street in Richland Industrial Park next to the Trinity Railway Express station. The building now houses Coastal Marine and Vital Records Control.

While researching this post I realized that every Saturday for the last two years I have biked past the 1957 Waples-Platter facility at 7133 Burns Street in Richland Industrial Park next to the Trinity Railway Express station. The building now houses Coastal Marine and Vital Records Control.

In 1982, one hundred years after Fannie Waples married Andrew Fox Platter, Oklahoma City-based Fleming Companies Inc. bought five of the six Waples-Platter divisions of Fort Worth.

In 1983 American Home Products of New York bought the sixth and last: Ranch Style Inc.

The Ranch Style plant, located just west of the Poly Freeway and south of Lancaster Avenue, canned its last bean in 2010. But the building has been preserved. In fact, it has been preserved in alcohol:

The plant is now the home of Trinity River Distillery, the big “Ranch Style” sign facing the freeway replaced by one for the distillery’s Texas Silver Star Whiskey.

The plant is now the home of Trinity River Distillery, the big “Ranch Style” sign facing the freeway replaced by one for the distillery’s Texas Silver Star Whiskey.

As for Paul Waples’s country estate, in 2002 political consultant Scott Howell bought the forty remaining acres of the property from the Waples family, restored much of it, and now rents it as a special-events venue:

As for Paul Waples’s country estate, in 2002 political consultant Scott Howell bought the forty remaining acres of the property from the Waples family, restored much of it, and now rents it as a special-events venue:

Howell Farms at Waples-Platter.

Howell Farms at Waples-Platter.

The barn now has chandeliers and a dance floor.

The barn now has chandeliers and a dance floor.

A caretaker’s cottage of native sandstone dates to the 1930s.

A caretaker’s cottage of native sandstone dates to the 1930s.

The stone-and-iron entrance gate with the W monogram survives.

The stone-and-iron entrance gate with the W monogram survives.

The main house has not been restored but retains its high ceilings and ornate brass doorknobs. Its porches have views all around.

The main house has not been restored but retains its high ceilings and ornate brass doorknobs. Its porches have views all around.

Details of the front of the house.

Details of the front of the house.

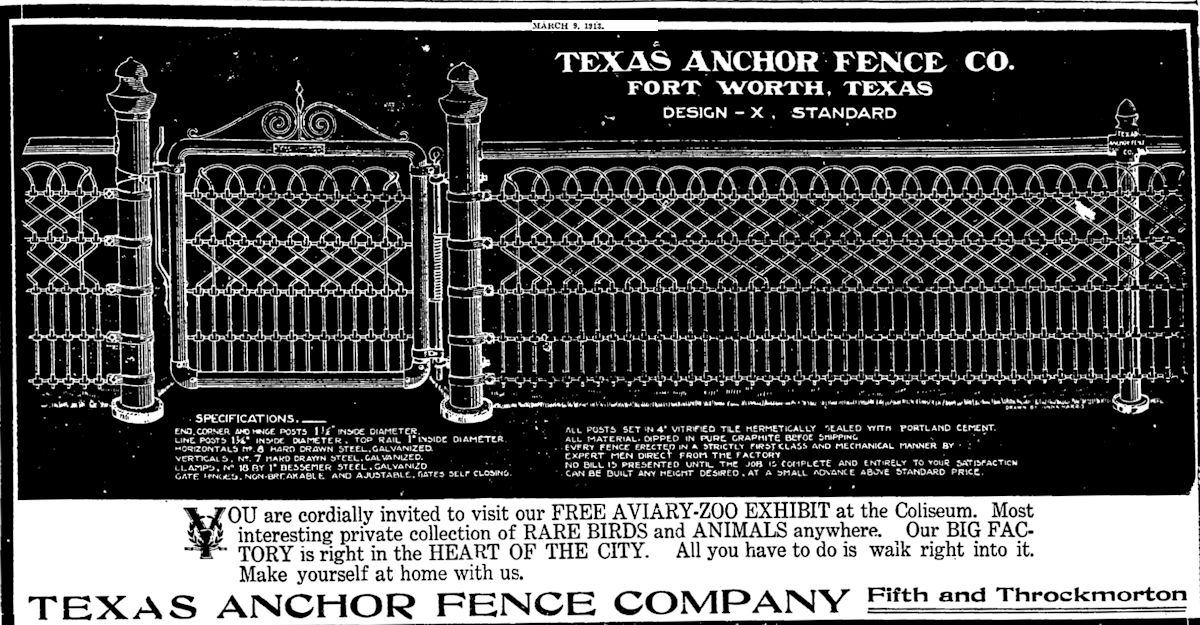

The wire fence along the front of the property is typical of the early 1900s and may have been made by Fort Worth’s Texas Anchor Fence Company.

The wire fence along the front of the property is typical of the early 1900s and may have been made by Fort Worth’s Texas Anchor Fence Company.

Today, as in 1916, to reach the highway from the Waples estate you must use the private driveway. The interurban track no longer crosses the driveway. But the Texas & Pacific tracks do.

Today, as in 1916, to reach the highway from the Waples estate you must use the private driveway. The interurban track no longer crosses the driveway. But the Texas & Pacific tracks do.

Look both ways.

Look both ways.

Paul Waples (Part 2): At the Foot of the Hill, a History Mystery

Does anyone know who the General Contractor was for the Waples Platter Building in Fort Worth, Texas?

Waples in 1893 apparently bought the property of Fort Worth Grocery Company, which began business in 1885. So the building at Lancaster and Jones was already there in 1893. I have seen nothing on who the general contractor was.

My daughter is getting married at the Howell Family Farms soon so I was researching that venue and came upon this article. What a fun read, both parts! I thoroughly enjoyed it except now our wedding planning will probably be interrupted by examining the area and theorizing for myself the purpose of the stairs to nowhere and other areas.

Thank you, Mr. Boyer. It’s a beautiful property, even without its history. Congratulations to your daughter. And look twice crossing those tracks!

Mike, this is another stunner, & one that hits close to home. My husband worked for Ranch Style Beans for 20 years & often talked about the history with the Waples family.

Thanks, Sarah. This one was Hometown by Handlebar’s one-thousandth post on its eighth birthday, and I wanted something special. Part 2 is probably more than anyone wants to read, but I think I found a small piece of Fort Worth history.