What a year 1927 was for the legends of cinema: Al Jolson and his The Jazz Singer, Fritz Lang and his Metropolis, Alfred Hitchcock and his The Lodger, Lorene Van Voast and Mary Elizabeth Isleib and their Sauce and Applesauce.

What? You say you never heard of the last two?

Well! Get hep. How can you ever hope to be the bee’s knees if you don’t know your onions?

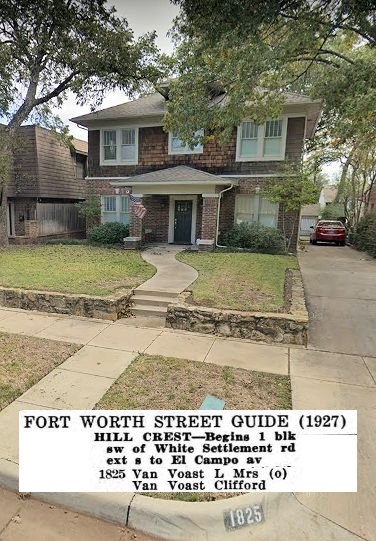

Lorene Van Voast was perhaps the most heralded screenwriter to come out of 1825 Hillcrest Avenue.

Lorene Van Voast was perhaps the most heralded screenwriter to come out of 1825 Hillcrest Avenue.

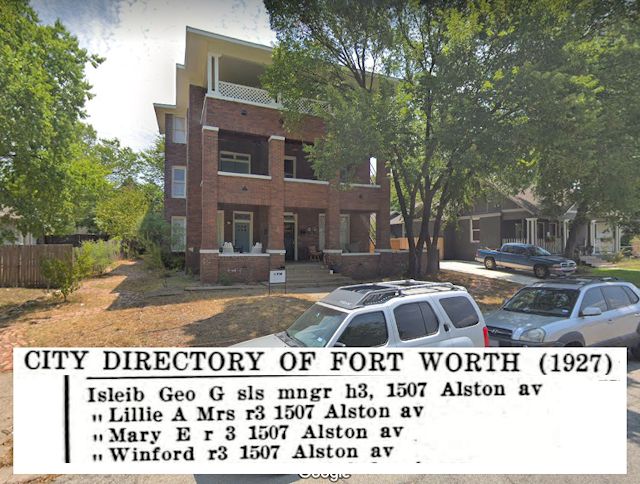

Likewise, Mary Elizabeth Isleib was perhaps the most glamorous starlet to emerge from 1507 Alston Avenue.

Likewise, Mary Elizabeth Isleib was perhaps the most glamorous starlet to emerge from 1507 Alston Avenue.

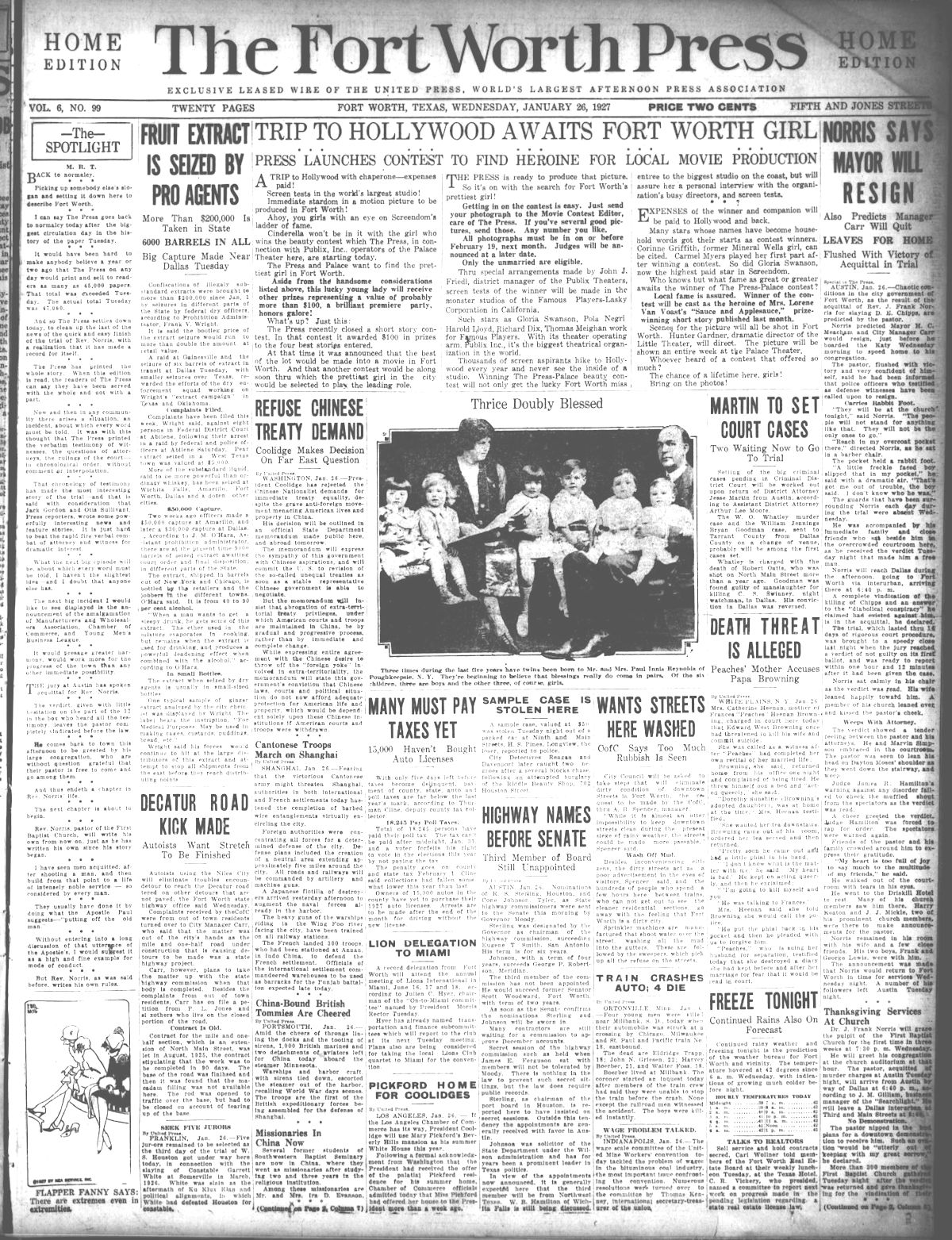

See, in 1927 the Metroplex was suffering a severe case of movie madness. Three movies using local talent as screenwriters and actors were shot in Fort Worth and Dallas as part of a nationwide publicity campaign by Famous Players-Lasky Corporation, a motion picture and distribution company that owned Paramount Pictures, which owned Publix, a chain of almost two thousand theaters, including the Worth and Palace in Fort Worth and the Palace in Dallas.

The first of the three Metroplex movies was sponsored by the Fort Worth Press and the Palace Theater.

The Palace had opened in 1919.

The Palace had opened in 1919.

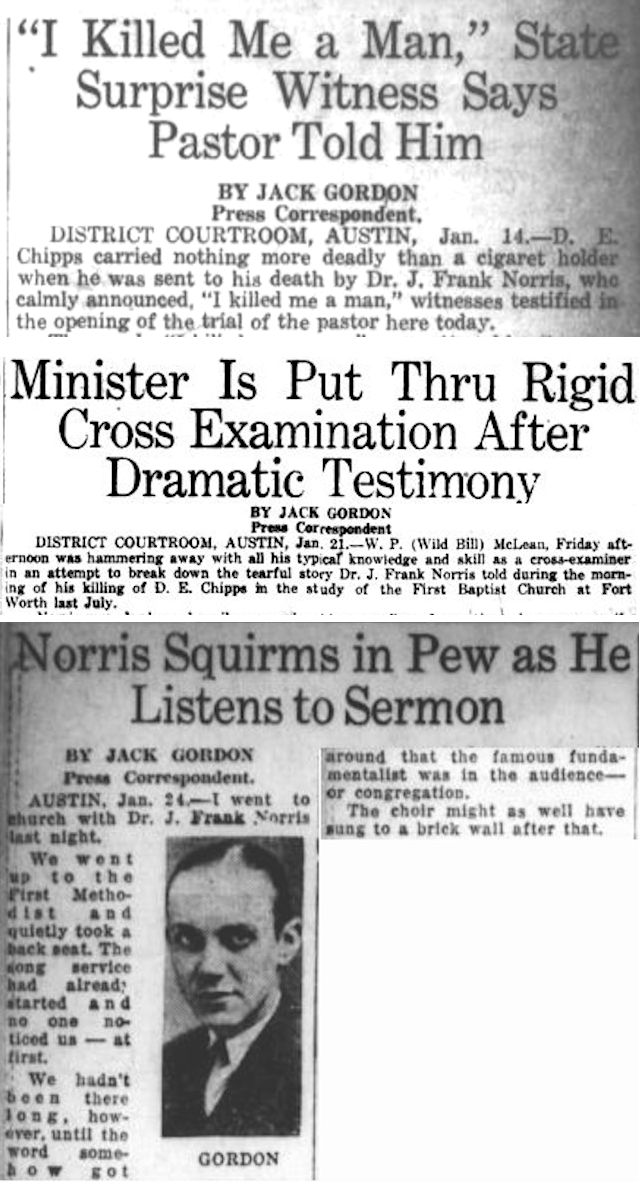

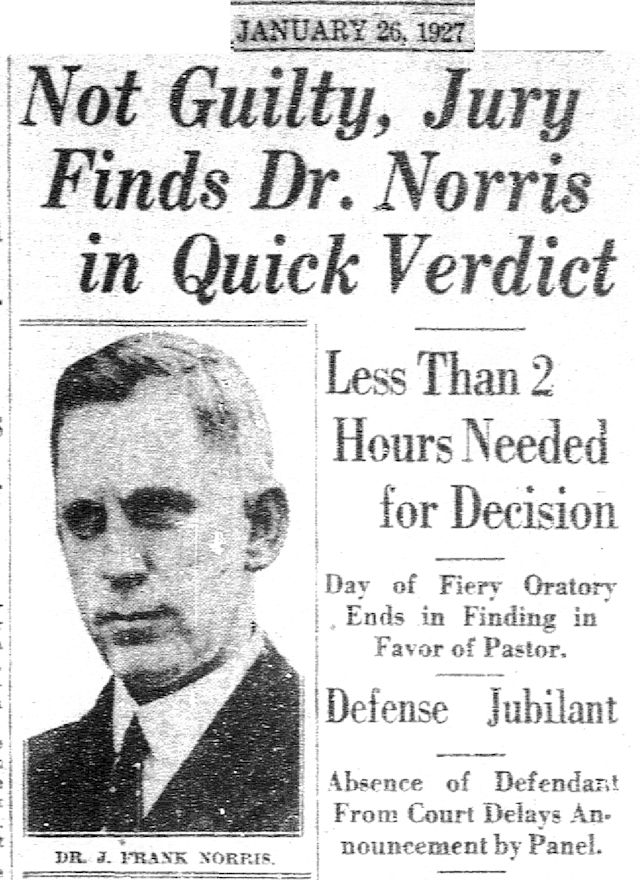

Whereas the stodgy Star-Telegram and Dallas Morning News would confine coverage of their movie projects to their inside entertainment page, the spritely Press plastered coverage of its movie project across the front page, the frilliness of the subject contrasting with dire headlines about natural disasters and war in China and crime, especially the murder trial of J. Frank Norris.

In fact, perceiving Norris’s murder trial as high drama, the Press assigned its theater writer, twenty-five-year-old Robert Jackson (“Jack”) Gordon, to cover the trial in Austin.

On January 26—the day newspapers announced that Norris had been acquitted—Gordon hurried back to Fort Worth and, clearing the throat of his typewriter, switched from his somber courtroom reporter’s voice to his breezy theater writer’s voice, and the Press began promoting the Press-Palace all-Fort Worth movie next to a story about Norris predicting that the mayor of Fort Worth would resign because of the acquittal. Norris said Mayor H. C. Meacham was part of a conspiracy against him.

On January 26—the day newspapers announced that Norris had been acquitted—Gordon hurried back to Fort Worth and, clearing the throat of his typewriter, switched from his somber courtroom reporter’s voice to his breezy theater writer’s voice, and the Press began promoting the Press-Palace all-Fort Worth movie next to a story about Norris predicting that the mayor of Fort Worth would resign because of the acquittal. Norris said Mayor H. C. Meacham was part of a conspiracy against him.

On front page after front page from January through April Gordon and the Press promoted first the contests and auditions to select the movie’s heroine and supporting cast and finally the filming. In 1927 most people would not have known the conventions of a film script, so the Press instead held a short story contest. Lorene Van Voast’s “Sauce and Applesauce” was the winner and became the basis of the script.

On front page after front page from January through April Gordon and the Press promoted first the contests and auditions to select the movie’s heroine and supporting cast and finally the filming. In 1927 most people would not have known the conventions of a film script, so the Press instead held a short story contest. Lorene Van Voast’s “Sauce and Applesauce” was the winner and became the basis of the script.

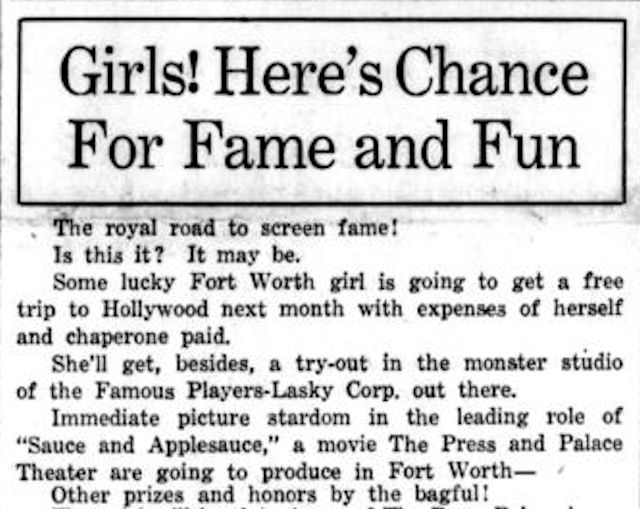

The Press trumpeted the benefits that would accrue to the winner of the beauty contest that would determine the star of the movie:

The Press trumpeted the benefits that would accrue to the winner of the beauty contest that would determine the star of the movie:

She would be feted at a party at the Palace Theater when the movie premiered.

As star of the all-Fort Worth movie, “local fame is assured” her, the Press promised. Moreover, she would win a chance at Hollywood stardom: a chaperoned trip to Hollywood to be interviewed by directors and take a screen test for Famous Players-Lasky Corporation. She would “meet oodles of movie stars.”

The Press reminded its readers that Corinne Griffith, who lived briefly in Mineral Wells and became known as “the Orchid of the Screen,” and Gloria Swanson (“now the highest paid star in Screendom”) had gotten their start in Hollywood by winning such beauty contests.

“Who knows but what fame as great or greater awaits the winner of The Press-Palace contest?”

The Press invited single women to submit photos to its movie contest editor. Almost four hundred women did so.

In the first assessment of photos, five judges—Fort Worth residents—could consider only beauty and “photographic possibilities,” not acting ability.

But after ten finalists were selected for their “photographic possibilities,” they were given scenes to perform so judges could assess grace and expressiveness.

Then the winner was selected.

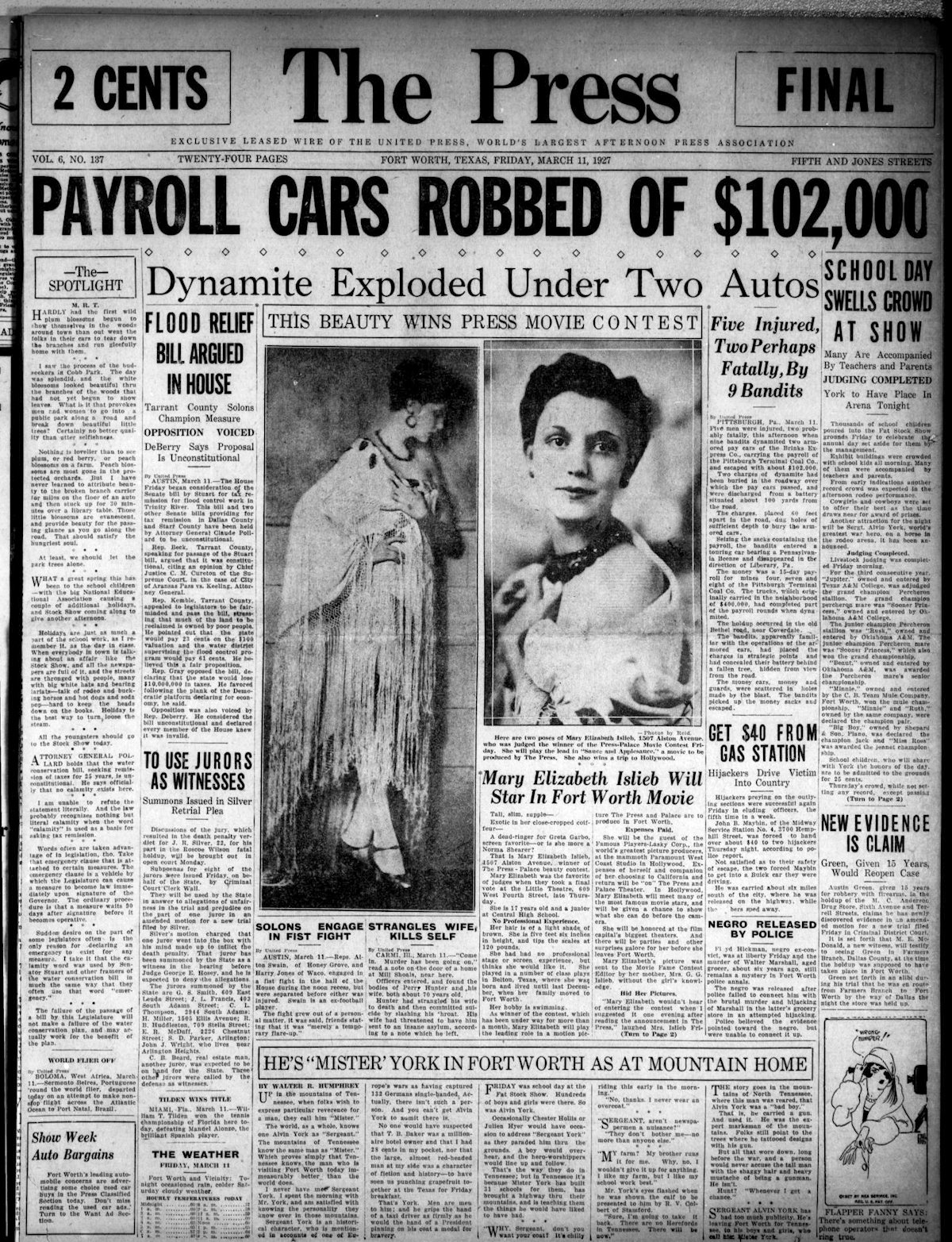

She was Mary Elizabeth Isleib, seventeen, a junior at Central High.

She was Mary Elizabeth Isleib, seventeen, a junior at Central High.

Her mother told the Press that Mary had scoffed at the idea of entering the contest and even went so far as to hide her best photos. But her mother submitted two that Mary had overlooked.

The Press gushed of Mary: “Tall, slim, supple—Exotic in her close-cropped coiffeur—A dead-ringer for Greta Garbo, screen favorite, or is she more a Norma Shearer?”

The supporting cast included a local amateur actor, a judge, and a city policeman.

A. P. Mitchell Auto Company provided a Cadillac for the production.

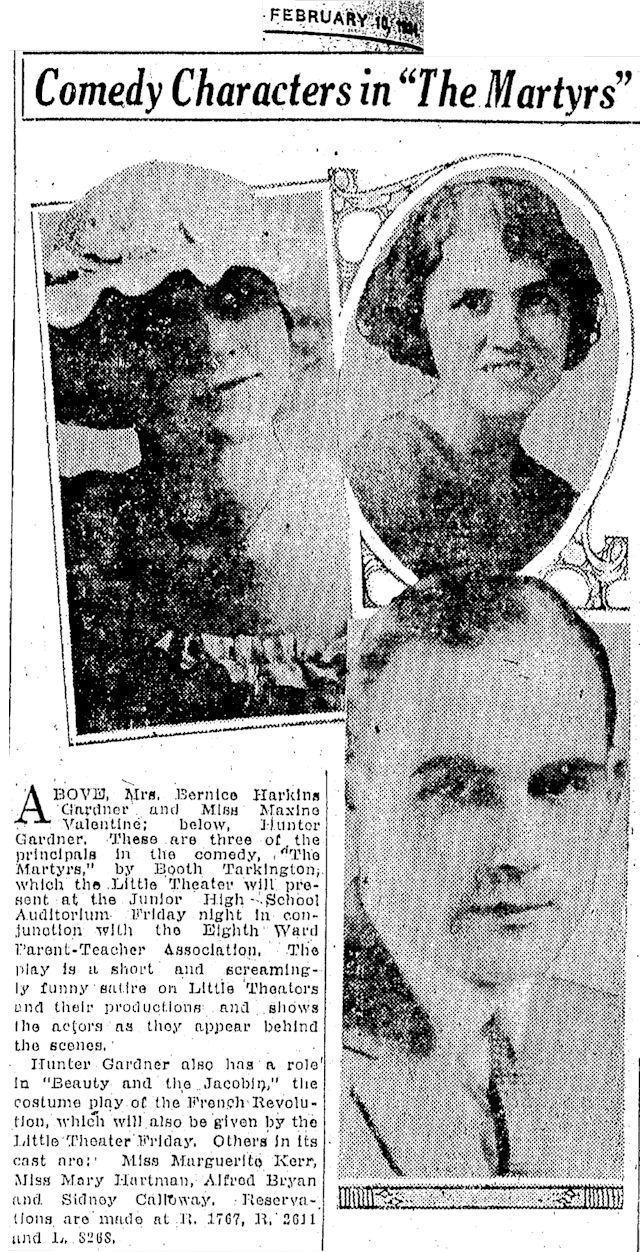

Director of the movie was Hunter Gardner, actor and director of Fort Worth’s Little Theater. Little Theater had been founded in 1921 as the Vagabond Players. (Another Vagabond Player was future Pulitzer Prize winner Katherine Anne Porter.)

Director of the movie was Hunter Gardner, actor and director of Fort Worth’s Little Theater. Little Theater had been founded in 1921 as the Vagabond Players. (Another Vagabond Player was future Pulitzer Prize winner Katherine Anne Porter.)

With the Sauce and Applesauce script, heroine, supporting cast, and director selected, the next order of business was scouting locations. The script called for a farmhouse. Jack Gordon helped scout the area to find a suitable farmhouse. The home of W. M. Eagle—with its “big, windswept porches”—in Riverside was selected.

The script also called for a horse. Feedstore operator Charley Klimist lent “heavyweight” Ben to the movie production.

Now it was almost time to make some movie magic. Just one more task: Before filming of Sauce and Applesauce began, director Gardner gave Mary “a long lesson” (ninety minutes) “in the principles of movie acting,” and quicker’n you can say, “All right, Mr. DeMille,” she was ready for her close-up.

Filming began on March 23 at the Eagle farm in Riverside. Encouraged by the Press, the public came to watch.

But soon after filming began, just as Ben the heavyweight horse was beginning to enjoy his celebrity, owner Charley Klimist up and sold him! One day Ben was in the limelight, the star of screen and stable; the next day he belonged to a teamster and was “hauling rock for a city sewer project.”

I’ll bet Mr. Ed was never treated so shabbily!

The show must go on. The movie company soon found a replacement: former racehorse Bailey D. Bailey D, his owner said, drank three cups of coffee each morning—from a cup.

As Gordon reported on the movie production, he sprinkled in explanations of the technical side of state-of-the-art filmmaking in 1927. For example, he explained that because in the beginning of the film Mary had to look haggard—with hollow cheeks—rouge was applied to her cheeks because red appears black on film.

The Press explained that movie film, unlike photographs, can’t be touched up after the fact, so actors must apply makeup before filming. Actors wore yellow greasepaint that looked “little short of hideous” in person but was flattering on film.

Gordon explained moviemaking techniques that we take for granted today. For example, to film close-ups of Mary’s changing expressions as she drove a buggy, while Gordon “cranked” the camera a man off camera rocked the parked buggy to make it appear to be rolling.

“When the picture is thrown on the Palace screen,” Gordon wrote, “nobody in the world would guess the buggy wasn’t moving. That’s just one of the sundry tricks we movie producers use.”

Moviemaking terms that we are familiar with today were new to readers in 1927. Thus, the Press placed terms such as shoot and rushes and location in quotation marks.

Gordon was given the lofty title of “assistant director,” and as such he felt it only fitting that he be provided with pair of “knickers” (jodhpurs). And, yes, Gordon pointed out that Gardner directed with a megaphone.

Gordon was given the lofty title of “assistant director,” and as such he felt it only fitting that he be provided with pair of “knickers” (jodhpurs). And, yes, Gordon pointed out that Gardner directed with a megaphone.

Sauce and Applesauce—as well as the Star-Telegram and Dallas Morning News movies—almost certainly was a silent movie, with caption cards inserted to show dialog and sounds. The movie probably was a two-reeler (20-24 minutes long).

By today’s standards the plot was simple.

In the opening scene, filmed at the Eagle farmhouse, Mary, the young wife of a middle-aged farmer, is washing clothes in a tub. Her life is drudgery. Her husband Alf is a miser.

Mary wears a “long, old-fashioned gingham dress borrowed from her mother” and appears “work-worn and untidy.”

In a later scene Mary asks her husband for a new dress. He refuses.

Still later Mary is driving her horse and buggy to town. She is taking butter and eggs to sell and $500 in cash to deposit in a bank.

Suddenly she has had enough.

Mary gets a close-up as she reaches her “dramatic decision.”

Gordon wrote of the star: “She is going to have a chance to do some high-powered acting.”

“Sick of the tight-fisted methods of her worse half, she decides to blow the ‘wad’ for clothes, and let the worst come.”

Then Mary is shown “getting diked out in a downtown department store” and getting the latest “ponjola bob” hair-do. Then she is shown “driving right up Main” “in the niftiest toggery from head to foot.”

A Cinderella-type transformation takes place as Mary becomes the “knockout” she really is and “steps out in the latest bob, the snappiest togs.”

But Mary soon realizes that one does not ride a bucolic buggy while wearing the latest bob and the snappiest togs. So, she has someone telephone her husband to ask him to come fetch her in the “flivver.” When hubby Alf gets the call, he fears that something “calamitous” has befallen his wife in the big sinful city.

“My God! To town, quick!” a caption card shrieks.

The camera then follows Alf’s “hysterical dash from the farm” in a neighbor’s fast roadster.

At this point you might be wondering what the title of the movie means. The Press did not explain. Sauce could refer to heroine Mary’s chutzpah in defying her miserly husband. And applesauce was 1920s slang synonymous with malarkey.

Likewise, Jack Gordon only teased the movie’s ending, writing of husband Alf when he reaches the transformed Mary sporting “the latest bob, the snappiest togs”:

“And when he sees Mary Elizabeth! And when he realizes what’s happened to his five hundred—!

“Folks, it’s going to be a snappy flicker!”

That snappy flicker premiered on April 30, 1927 at the Palace Theater.

That snappy flicker premiered on April 30, 1927 at the Palace Theater.

It was the cat’s meow.