As long as trains roll down tracks, railroading will be a dangerous profession.

Huge engines with a jillion metal moving parts move those metal moving parts down iron rails at high speed, powered by fire and steam in the old days, by flammable diesel fuel today.

What could go wrong?

An example of what could go wrong occurred on the morning of March 29, 1913. Texas & Pacific train 15, a freight train known as the Mineola Dodger, had just left Handley headed for Fort Worth. Train 15 was pulled by T&P engine 325, built in 1903 by the ALCO-Cooke locomotive works in Paterson, New Jersey. Engine 325 was a 4-6-0 formation: four leading wheels, six driving wheels, no trailing wheels. The locomotive’s boiler weighed fifteen thousand pounds (the equivalent of three 1963 Lincoln Continentals).

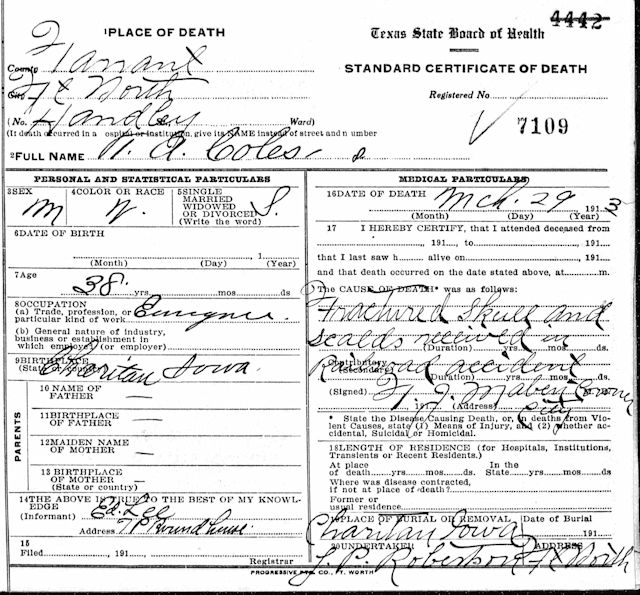

Tom Coles was the engineer of the Mineola Dodger that day.

Tom Coles was the engineer of the Mineola Dodger that day.

In Handley Coles had waited for a passenger train to pass and then, about 8 a.m., put his train into motion toward Fort Worth. But moments later Coles stopped the train just east of today’s Loop 820 and south of Lancaster Avenue (near the Dixie House Cafe).

In Handley Coles had waited for a passenger train to pass and then, about 8 a.m., put his train into motion toward Fort Worth. But moments later Coles stopped the train just east of today’s Loop 820 and south of Lancaster Avenue (near the Dixie House Cafe).

Cole stopped the train over the underpass where the interurban track (yellow line) crossed under Old Handley Road and the T&P tracks. The underpass under Old Handley Road is still there. A trickle of water flows through what is left of the interurban underpass under the T&P railroad tracks.

Interviewed later, witnesses said they saw Coles, wearing a derby hat, on the ground beside the locomotive. They said he was “oiling around,” which was the practice of an engineer to walk around a locomotive to check bearings for excessive heating by touching them with his hand and oiling as needed.

Witnesses said the train’s fireman, J. T. Moore, also was on the ground, and the brakeman, George Thomas, was on the ground about fifty feet away in front of the locomotive.

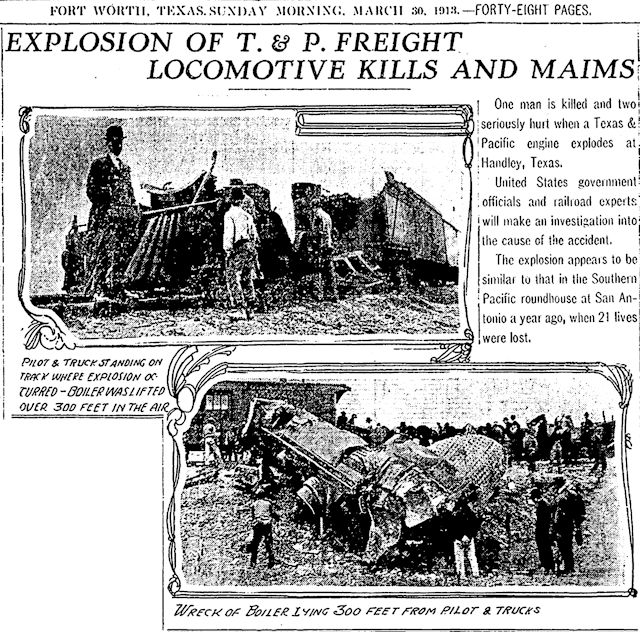

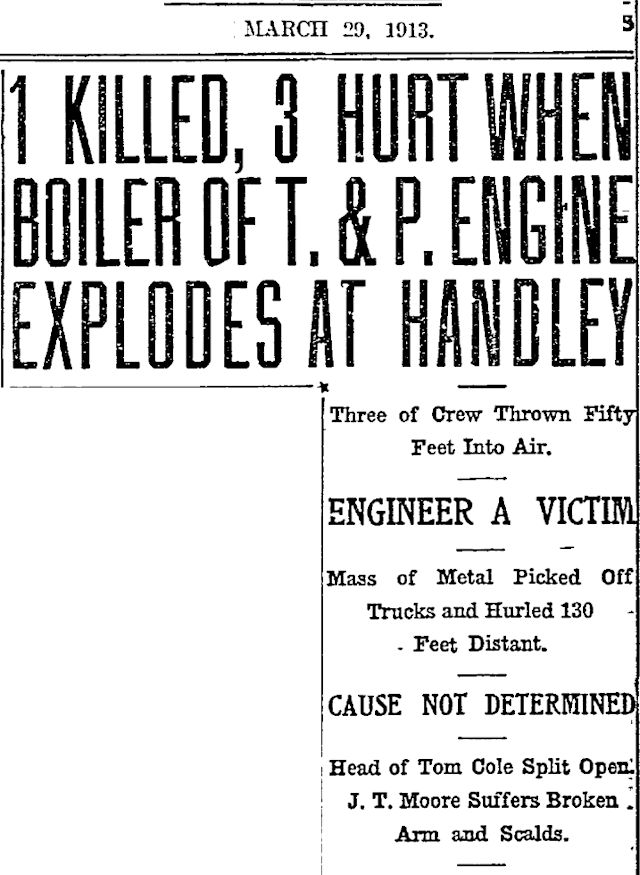

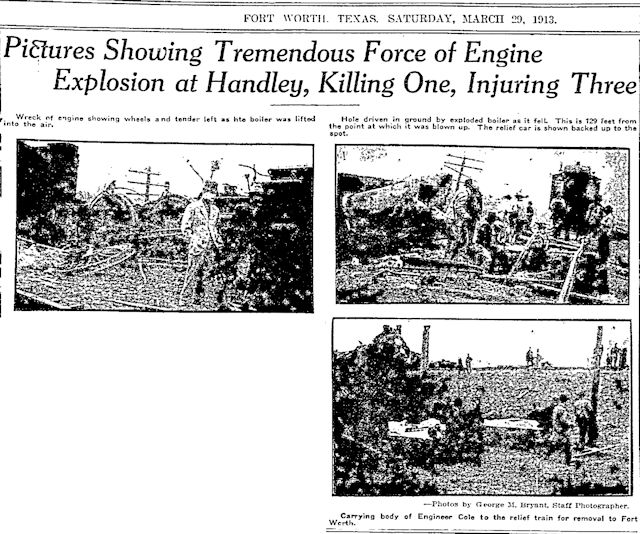

Suddenly a boom shattered the air and shook the ground. The three railroad men disappeared in a cloud of steam and smoke as the cloud began to rain fragments of metal piping and plating, and the fifteen-thousand-pound boiler, torn loose from the locomotive frame, rose out of the cloud and tumbled end over end through the air.

One hundred thirty feet from the locomotive frame the cylindrical boiler landed almost vertically on its end, embedding itself five feet in the ground. The shattered boiler, dripping water and hissing steam, slumped, teetered a few seconds, and fell over with a metallic crash.

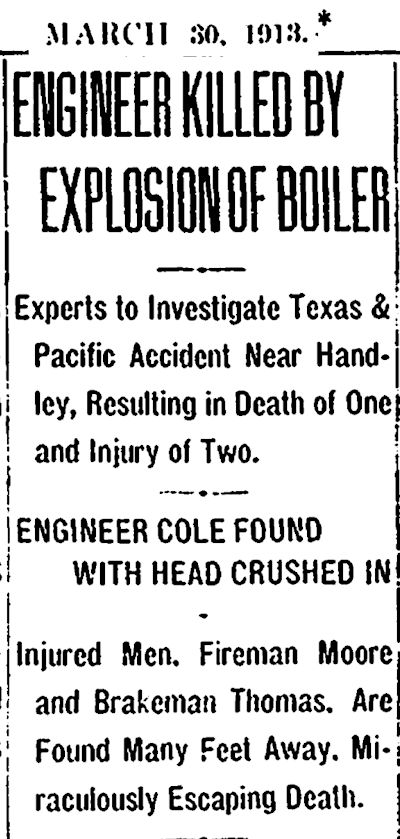

The Fort Worth Record wrote that the “boiler was lifted over 300 feet in the air” and was “a mass of twisted boiler plate and flues.” The boiler was split from end to end along the top.

Lesser debris was thrown hundreds of feet from the locomotive. The sand dome was propelled six hundred feet. The force of the explosion uncoupled the locomotive from its tender and propelled the boilerless locomotive thirty feet along the track.

Telegraph pole cross arms two hundred feet away were snapped by flying debris, and telegraph and telephone wires were downed.

The accident was front-page news in both the Star-Telegram and Record.

The accident was front-page news in both the Star-Telegram and Record.

T. I. Darnell of Handley witnessed the explosion. “I was almost jarred off my feet, and when I looked up the air was full of flying pieces of iron. . . . I saw dust, smoke, steam, and iron in the air.”

Darnell said the airborne boiler was “traveling slowly and turning over and over.”

The train’s engineer, fireman, and brakeman were hurled fifty feet into the air by the explosion.

Fireman J. T. Moore suffered a broken arm and scalds. Brakeman George Thomas suffered only shock. The boiler had sailed over his head.

But engineer Tom Coles was killed. His head had hit a railroad track when he landed.

But engineer Tom Coles was killed. His head had hit a railroad track when he landed.

The two injured men were given first aid by two Handley doctors, and a rescue train was dispatched from Fort Worth. On board the rescue train was Dr. Bacon Saunders, who was division surgeon of several railroads serving Fort Worth.

The two injured men were taken to St. Joseph Hospital, which had been founded by the Missouri Pacific railroad.

The explosion was heard a half-mile away, and a crowd soon gathered at the scene.

The explosion was heard a half-mile away, and a crowd soon gathered at the scene.

Walter “Smokey” Darr, who would grow up to be a locomotive engineer himself, was thirteen years old. Years later he recalled hearing the explosion and racing down the tracks to the accident scene. He recalled that engineer Coles died with his watch still running and his derby hat undamaged.

Witnesses speculated that Coles’s hat had been blown off his head as he was thrown into the air.

A T&P master mechanic arrived with the rescue train and began investigating the accident. The Star-Telegram said the mechanic would confer with experts of other railroads before reaching a conclusion about the cause of the explosion.

One early theory was that engineer Coles had discovered that the boiler was low on water and overheated and had stopped the train to refill the boiler. Perhaps the cold water hitting the overheated boiler caused the boiler to explode.

With engineer Coles dead, the key to the mystery lay with fireman Moore.

But Moore was too weak to be interviewed immediately after the explosion, and I found no followup newspaper reports on the investigation.

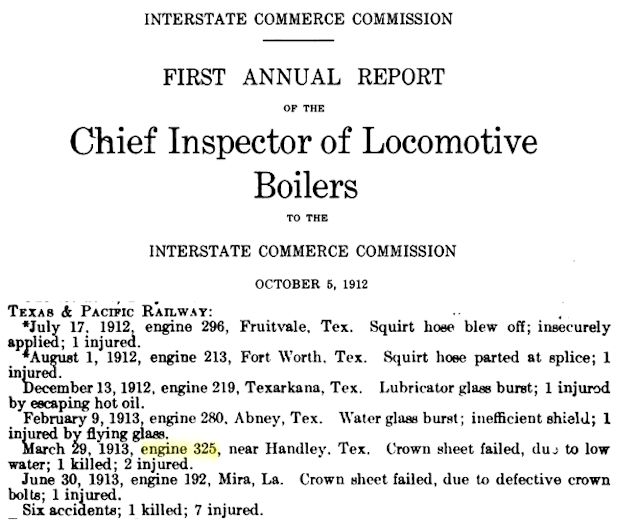

However, the 1913 annual report of the chief inspector of locomotive boilers to the Interstate Commerce Commission lists the cause of the accident as “Crown sheet failed, due to low water.”

However, the 1913 annual report of the chief inspector of locomotive boilers to the Interstate Commerce Commission lists the cause of the accident as “Crown sheet failed, due to low water.”

In fact, that annual report lists 302 crown sheet failures due to low water, resulting in accidents that injured dozens and killed several across the country.

According to that annual report, Tom Coles was the only T&P fatality.

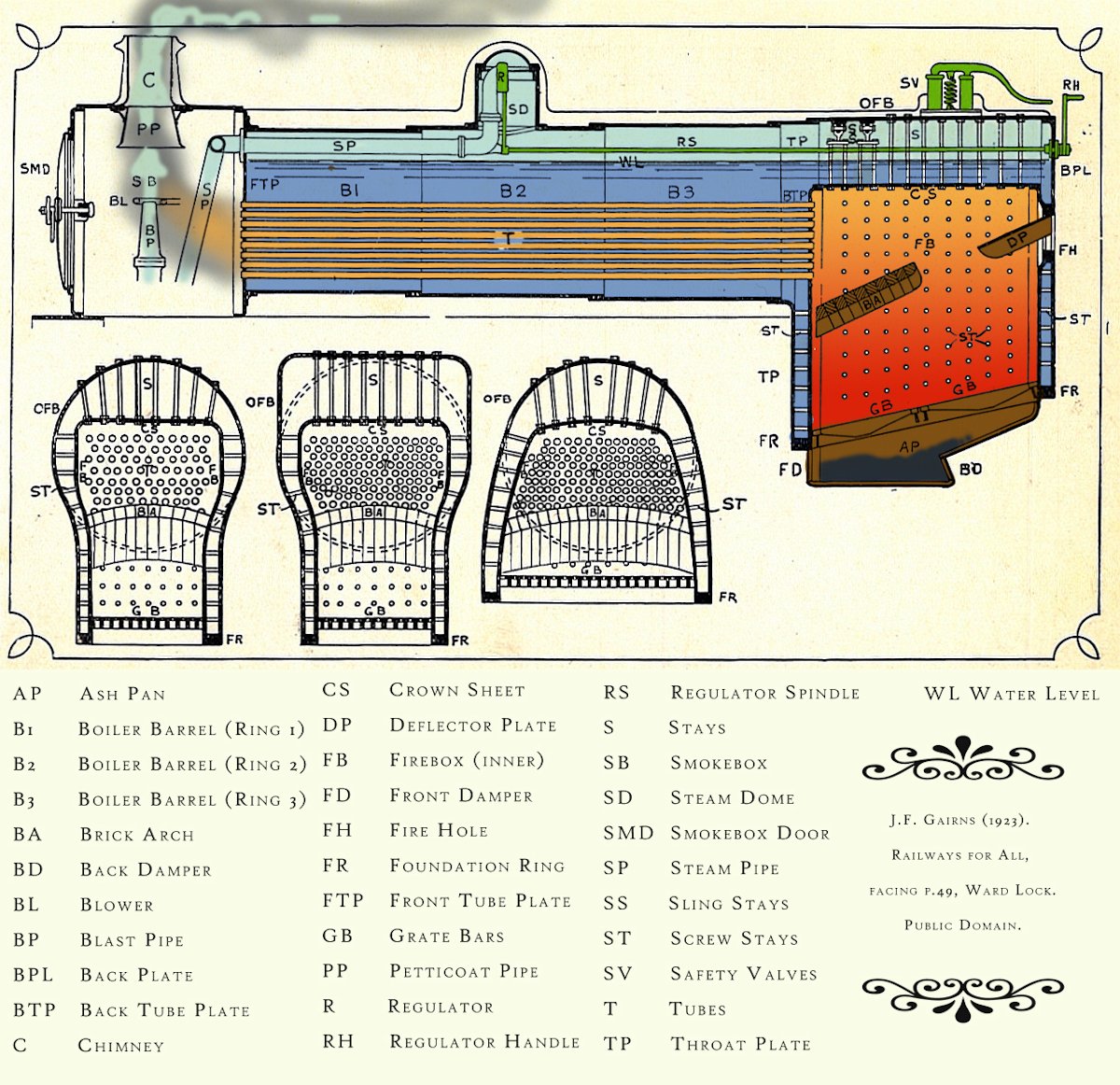

What was a crown sheet? A crown sheet was the top of the firebox at the cab end of a boiler on a locomotive. The firebox was where the fuel—wood or coal—was burned. Thus, the firebox was like a stove, and the crown sheet was like the stovetop. The crown sheet had to be covered by water at all times. If not, the crown sheet could become overheated, melt, and deform. This deformation could result in a boiler explosion. In fact, crown sheet failure due to low water, usually caused by human error, was the leading cause of locomotive boiler explosions during the age of steam.

What was a crown sheet? A crown sheet was the top of the firebox at the cab end of a boiler on a locomotive. The firebox was where the fuel—wood or coal—was burned. Thus, the firebox was like a stove, and the crown sheet was like the stovetop. The crown sheet had to be covered by water at all times. If not, the crown sheet could become overheated, melt, and deform. This deformation could result in a boiler explosion. In fact, crown sheet failure due to low water, usually caused by human error, was the leading cause of locomotive boiler explosions during the age of steam.

In this cross-section, the firebox (FB) and crown sheet (CS) are on the right.

Maintaining adequate water over the crown sheet typically was the responsibility of the fireman.

This thermal image shows the heat of a steam locomotive. To railroaders a locomotive boiler was the Grim Reaper on wheels. After all, a contraption that, when properly controlled, can create enough steam pressure to move a train of hundreds of tons can, when not properly controlled, be as destructive as a weapon of war. An explosion could turn a boiler into a grenade, ripping apart the boiler’s metal plating and propelling shards of plating like shrapnel. An explosion could turn a boiler into a missile, launching the boiler free of the locomotive frame and propelling it more or less intact into the air, as in the accident that killed Tom Coles.

This thermal image shows the heat of a steam locomotive. To railroaders a locomotive boiler was the Grim Reaper on wheels. After all, a contraption that, when properly controlled, can create enough steam pressure to move a train of hundreds of tons can, when not properly controlled, be as destructive as a weapon of war. An explosion could turn a boiler into a grenade, ripping apart the boiler’s metal plating and propelling shards of plating like shrapnel. An explosion could turn a boiler into a missile, launching the boiler free of the locomotive frame and propelling it more or less intact into the air, as in the accident that killed Tom Coles.

As in most disasters, at Handley the difference of a few seconds on a clock or a few degrees on a compass could have altered the death toll. It could have been worse: The passenger train had passed engine 325 moments before the explosion; interurban trains ran under the T&P track where the Mineola Dodger was parked; homes were located nearby; a work detail of more than fifty men was grading right-of-way within one hundred yards of the locomotive, but the boiler was hurled in the other direction. It could have been better: If engineer Coles had been standing where his brakeman was standing, Coles might have suffered only shock, maybe even kept his derby hat on.

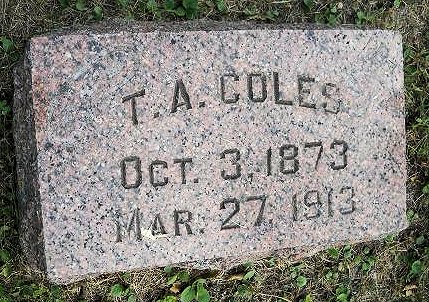

Tom Coles is buried in his native Iowa. He was thirty-nine years old.

Tom Coles is buried in his native Iowa. He was thirty-nine years old.

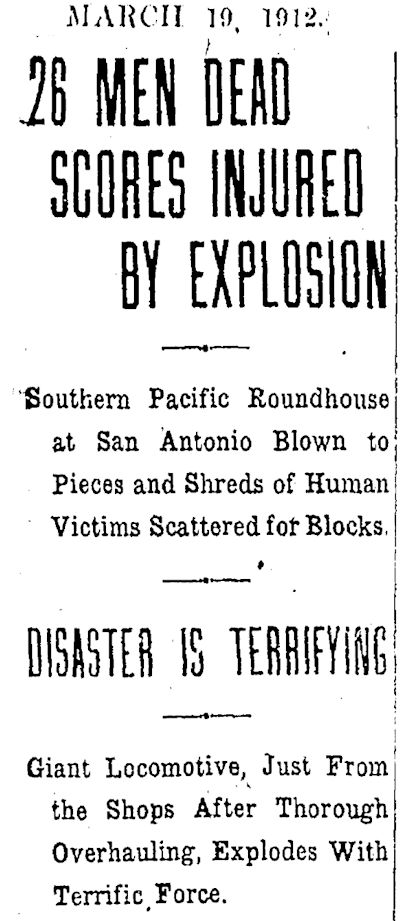

Footnote 1: The Record photo caption above refers to an explosion at the Southern Pacific roundhouse in San Antonio in 1912. That explosion was the worst railroad boiler explosion in U.S. history. It occurred when the boiler of an engine in the Southern Pacific roundhouse blew up with the force of a bomb. The roundhouse was destroyed, and twenty-six people (not twenty-one as reported by the Record) were killed. The firebox’s crown sheet was propelled almost two thousand feet into the air. But that explosion was caused by a faulty valve.

Footnote 1: The Record photo caption above refers to an explosion at the Southern Pacific roundhouse in San Antonio in 1912. That explosion was the worst railroad boiler explosion in U.S. history. It occurred when the boiler of an engine in the Southern Pacific roundhouse blew up with the force of a bomb. The roundhouse was destroyed, and twenty-six people (not twenty-one as reported by the Record) were killed. The firebox’s crown sheet was propelled almost two thousand feet into the air. But that explosion was caused by a faulty valve.

Footnote 2: Less than three miles east of where engineer Tom Coles was killed, in 1885 T&P engine 642 plunged into Village Creek, killing fireman J. G. Habeck, and in 1916 an interurban train killed Paul Waples.

(Thanks to Dennis Hogan for his help.)

Excellent sleuthing supported by your contemporary photos! As always, a top notch report.

Could not have done it without you. Thanks again.