It was the first of the three theaters on downtown’s Show Row. In fact, the Palace made the Worth and the Hollywood seem like cinematic whippersnappers.

The Palace’s first presentation (The Land of Nod) and its last (The Big Sleep) may have had slumbersome titles, but in between were almost seventy years of lively entertainment—opera, vaudeville, silent movies, talkies, personal appearances by motion picture elite—that inspired applause, bravos and boos, cheers and tears and plenty of popcorn.

In fact, by the time “The End” came for the Palace, the theater could trace its story back almost a century.

Culture came early to Cowtown—four years before the Short-Courtright shootout. In 1883 local capitalist Walter Huffman led a syndicate that built the Fort Worth Opera House at the corner of East 3rd and Rusk (now Commerce) streets. After Huffman died in 1890 Phil Greenwall bought the opera house from Huffman’s heirs and operated it as “Greenwall’s Opera House.” Greenwall and brother Henry were impresarios in Texas theater, managing a circuit of dozens of theaters across the state, booking live entertainment—stock companies, opera companies, burlesque, and other acts—and later movies.

In fact, by 1905 Greenwall’s was presenting the new phenomenon—moving pictures—although the theater continued to stress live entertainment.

In fact, by 1905 Greenwall’s was presenting the new phenomenon—moving pictures—although the theater continued to stress live entertainment.

But in 1908 the opera house was damaged by high winds. Architect Marshall Sanguinet advised Phil Greenwall that the building was not worth repairing. Greenwall decided to find someone to finance a replacement building.

But in 1908 the opera house was damaged by high winds. Architect Marshall Sanguinet advised Phil Greenwall that the building was not worth repairing. Greenwall decided to find someone to finance a replacement building.

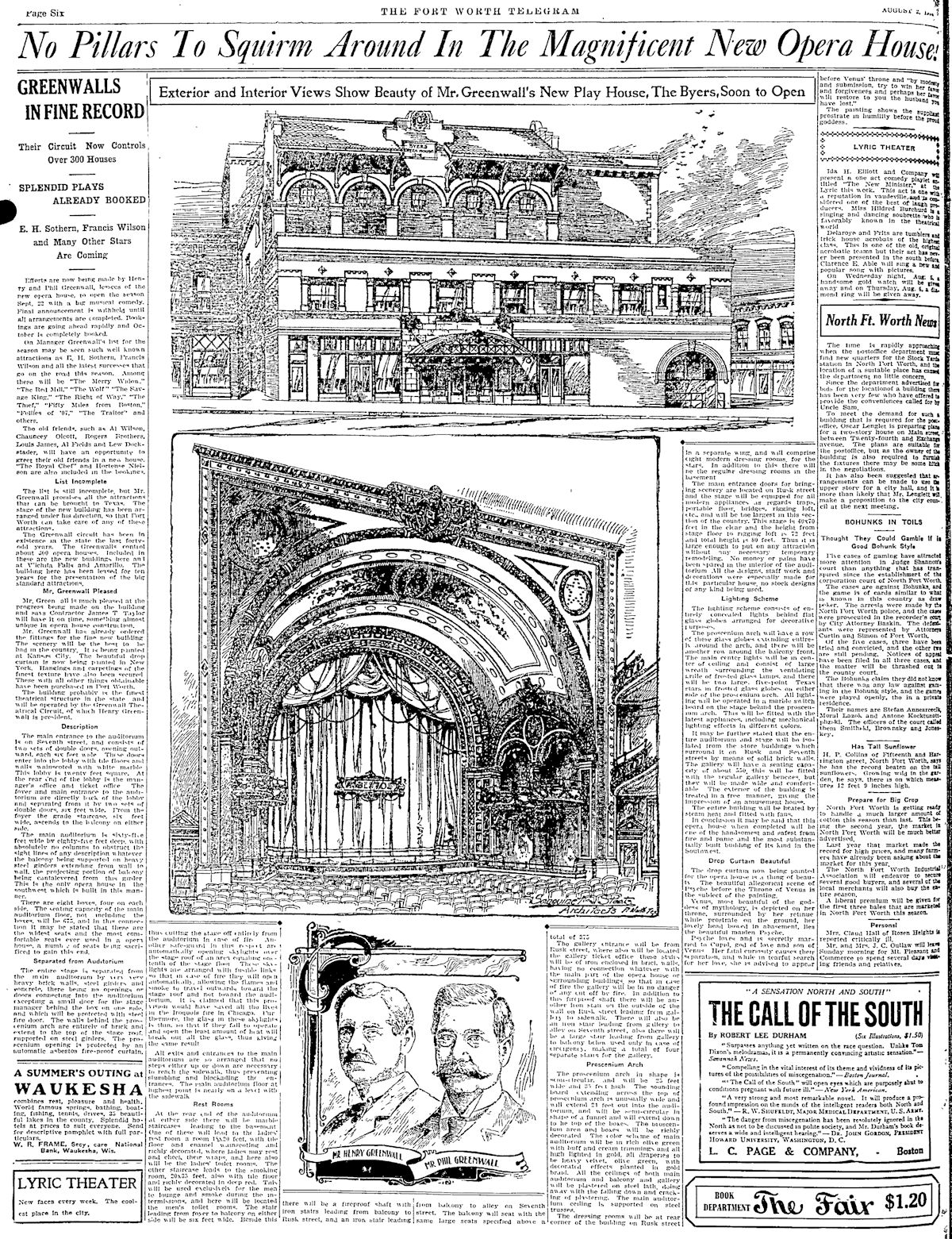

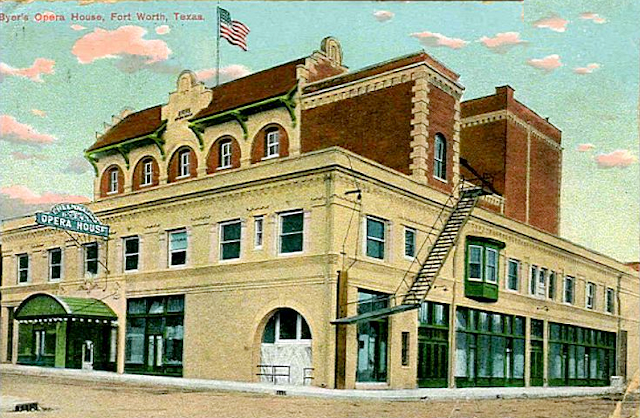

Local capitalist Andrew Thomas Byers financed the new building at East 7th and Rusk streets and leased it to Greenwall.

Local capitalist Andrew Thomas Byers financed the new building at East 7th and Rusk streets and leased it to Greenwall.

The new opera house had sixteen hundred seats, nineteen hundred lights, eight boxes, and no columns in the seating area to obstruct sightlines.

The new opera house had sixteen hundred seats, nineteen hundred lights, eight boxes, and no columns in the seating area to obstruct sightlines.

The lobby had tiled floors and walls with marble wainscoting. Sanguinet and Staats were the architects.

By now the Greenwall brothers managed more than three hundred theaters.

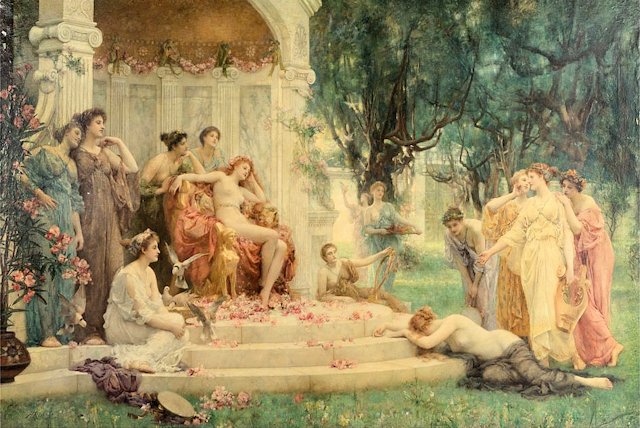

The handpainted drop curtain of the new opera house depicted the 1894 Henrietta Rae painting Psyche Before the Throne of Venus. (Painting from Wikimedia.)

The handpainted drop curtain of the new opera house depicted the 1894 Henrietta Rae painting Psyche Before the Throne of Venus. (Painting from Wikimedia.)

The opera house was known alternately as “Byers’ Opera House” and “Greenwall’s Opera House.”

By either name, the theater proclaimed itself the “handsomest theater in the South.”

The theater opened September 21, 1908 with the musical extravaganza The Land of Nod. Also on the bill was the “Dance of Salome,” which in 1908 was the talk of Europe and America. The dance was inspired by the biblical story, but the gauzy costume and “gyrations” of the actress portraying Salome were seen in some quarters as decidedly unbiblical, condemned from podium and pulpit.

The theater opened September 21, 1908 with the musical extravaganza The Land of Nod. Also on the bill was the “Dance of Salome,” which in 1908 was the talk of Europe and America. The dance was inspired by the biblical story, but the gauzy costume and “gyrations” of the actress portraying Salome were seen in some quarters as decidedly unbiblical, condemned from podium and pulpit.

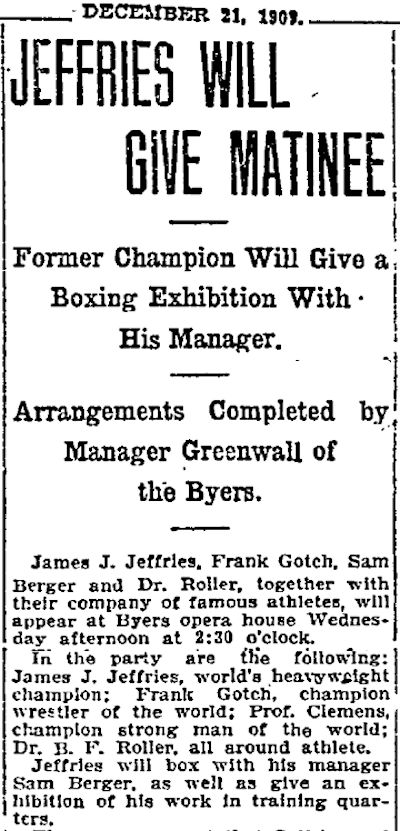

But the Byers was not all arias and adagios. In 1909 former heavyweight champion boxer Jim Jeffries gave an exhibition on the Byers stage. Boxers Jim Corbett and Bob Fitzsimmons also made personal appearances at the Byers.

But the Byers was not all arias and adagios. In 1909 former heavyweight champion boxer Jim Jeffries gave an exhibition on the Byers stage. Boxers Jim Corbett and Bob Fitzsimmons also made personal appearances at the Byers.

Verdi’s Il Trovatore was presented in 1910.

Verdi’s Il Trovatore was presented in 1910.

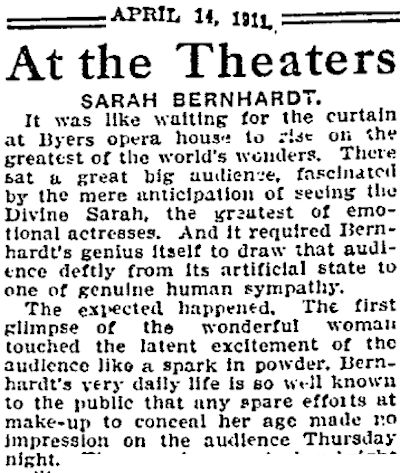

The “divine” Sarah Bernhardt trod the boards in 1911.

The “divine” Sarah Bernhardt trod the boards in 1911.

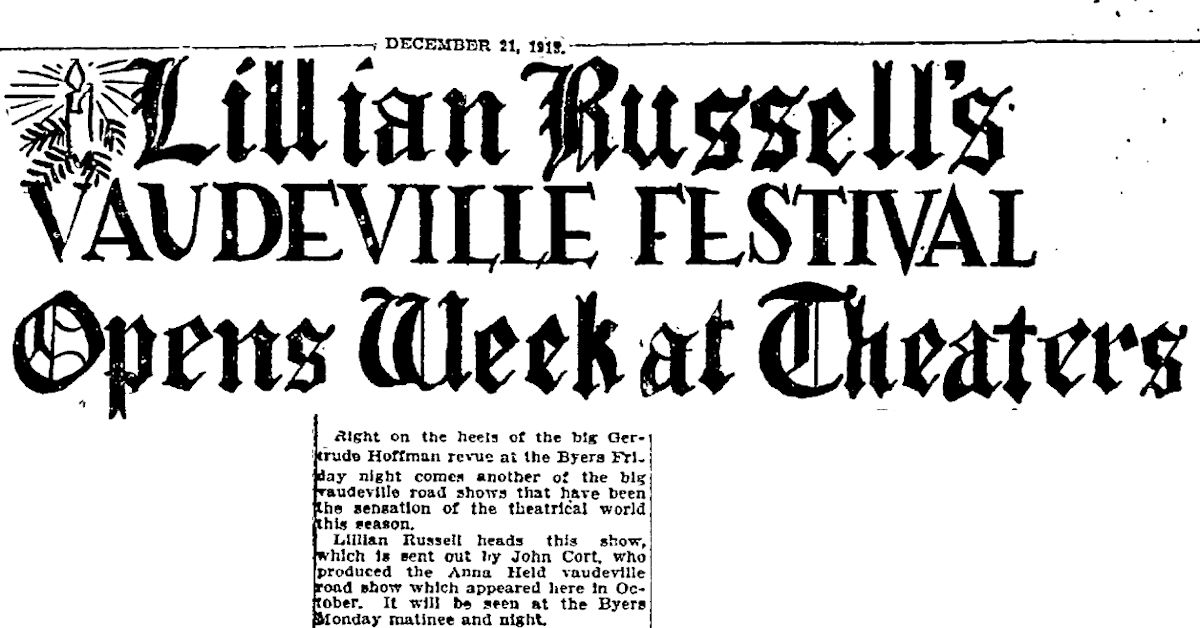

Followed by Lillian Russell in 1913.

Followed by Lillian Russell in 1913.

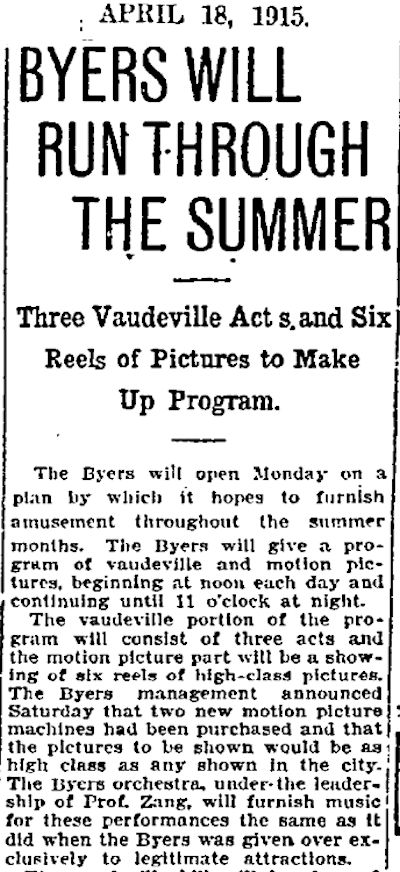

In 1915 Phil Greenwall, who had resisted booking vaudeville in favor of “legitimate theater,” gave in and began offering vaudeville along with movies at the Byers.

In 1915 Phil Greenwall, who had resisted booking vaudeville in favor of “legitimate theater,” gave in and began offering vaudeville along with movies at the Byers.

D. W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation had its Fort Worth premiere at the Byers in 1915.

D. W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation had its Fort Worth premiere at the Byers in 1915.

By 1916 Fort Worth had several theaters—including the Majestic—presenting live performances ranging from opera to vaudeville, melodramas to musicals, and moving pictures.

By 1916 Fort Worth had several theaters—including the Majestic—presenting live performances ranging from opera to vaudeville, melodramas to musicals, and moving pictures.

But popular taste was changing. Legitimate theater was yielding to vaudeville, which would yield to movies. The theaters and circuits had to follow suit.

But in 1916 Phil Greenwall sold his Byers lease to the Interstate Theater circuit, which, like the Greenwall brothers, had begun by booking live performances and transitioned into booking movies.

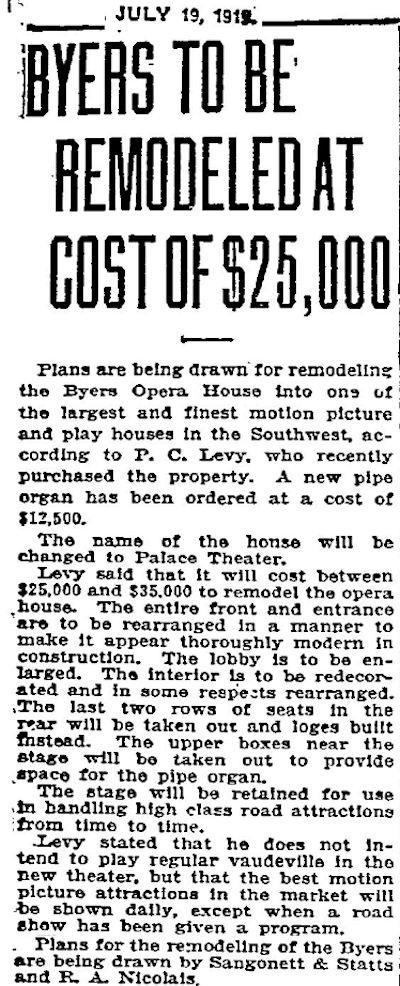

In 1919 Pierre Levy bought the Byers building and converted it into the first theater in town designed to show motion pictures (but it also had a stage “for high-class road attractions”).

In 1919 Pierre Levy bought the Byers building and converted it into the first theater in town designed to show motion pictures (but it also had a stage “for high-class road attractions”).

Architects Sanguinet and Staats, assisted by Raphael Nicholais, designed the new look. (Nicholais in 1923 would design R. O. Dulaney’s fine house on Elizabeth Boulevard.)

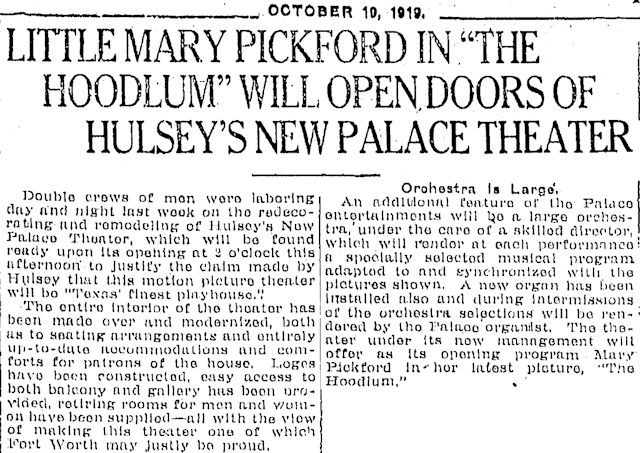

The interior of the theater was enlarged and customized for the motion picture experience. A new organ was installed. The theater would have a resident orchestra and conductor.

This photo shows how much the facade of the Palace had changed by 1964. The marquee was topped by the word PALACE in letters bright and large enough to be seen from the ticket queues at the Hollywood and Worth theaters.

This photo shows how much the facade of the Palace had changed by 1964. The marquee was topped by the word PALACE in letters bright and large enough to be seen from the ticket queues at the Hollywood and Worth theaters.

But to the right of the marquee can be seen some of the original brick detailing of the 1908 exterior. To the left is the edge of the 1930 Aviation Building (see below). (Photo from UNT Media Library.)

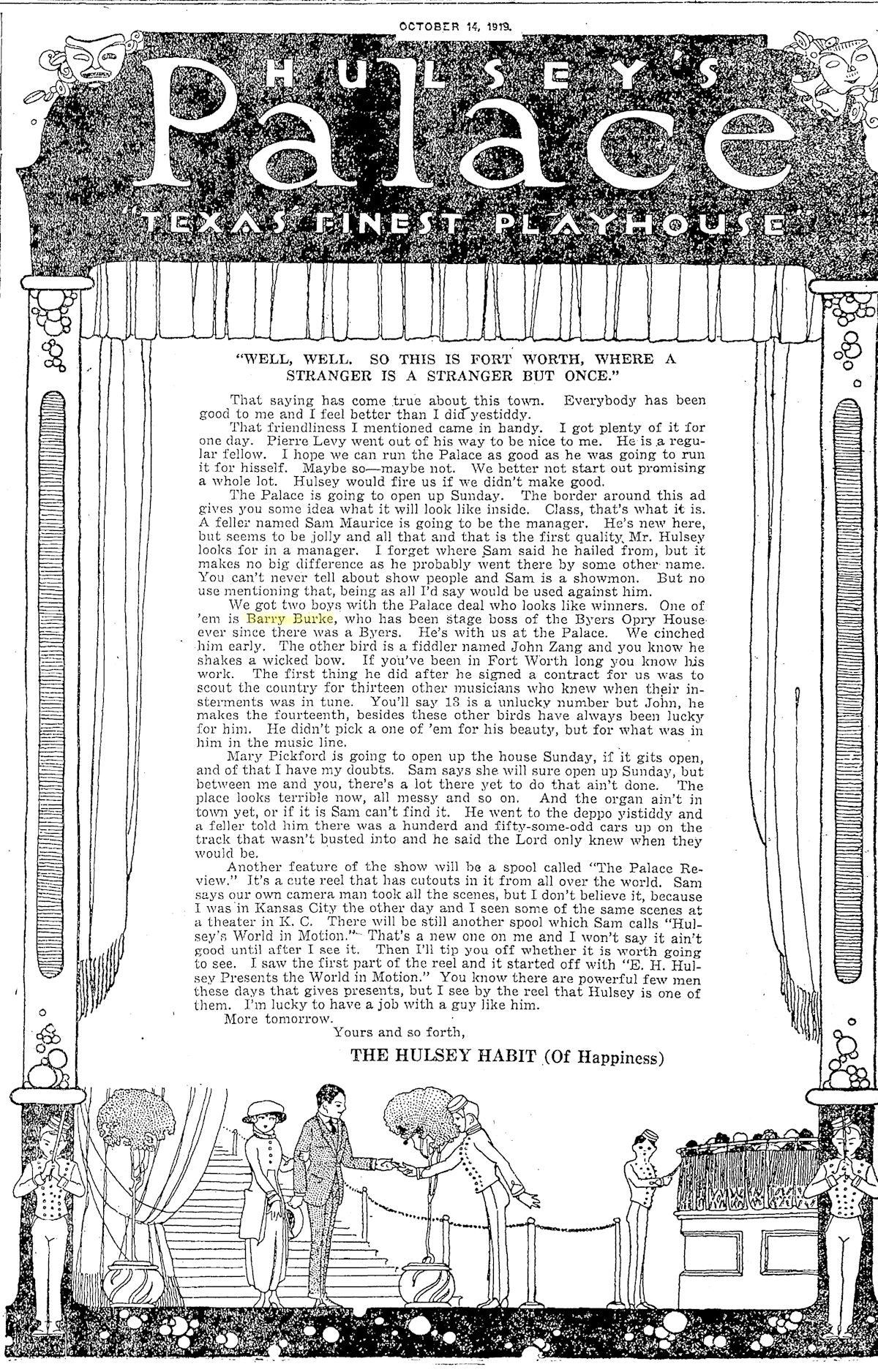

Levy sold the remodeled building to E. H. Hulsey of Dallas. Hulsey owned several theaters. In this rather folksy open letter, note the reference to Barry Burke (see Part 2).

Levy sold the remodeled building to E. H. Hulsey of Dallas. Hulsey owned several theaters. In this rather folksy open letter, note the reference to Barry Burke (see Part 2).

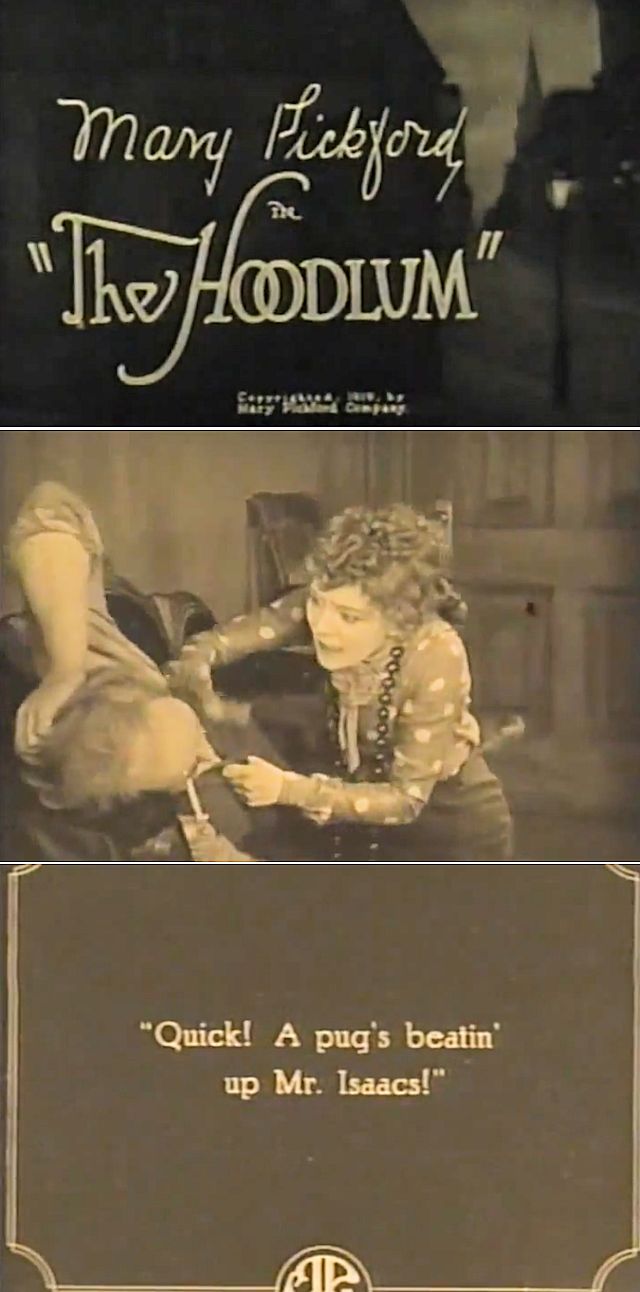

The Palace Theater opened on October 19, 1919 with The Hoodlum starring Mary Pickford.

The Palace Theater opened on October 19, 1919 with The Hoodlum starring Mary Pickford.

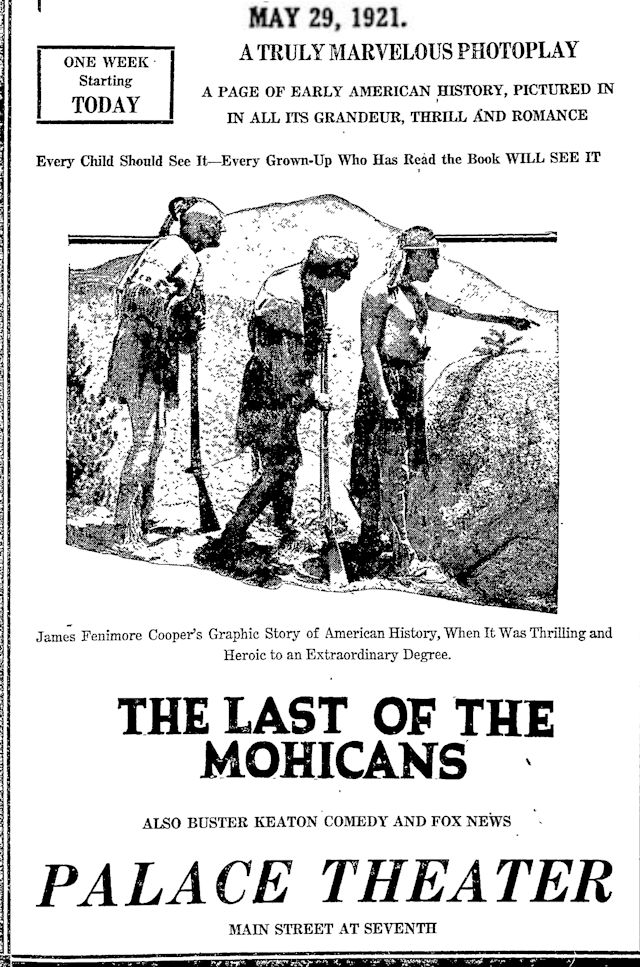

In 1921 the “truly marvelous photoplay” The Last of the Mohicans was presented.

In 1921 the “truly marvelous photoplay” The Last of the Mohicans was presented.

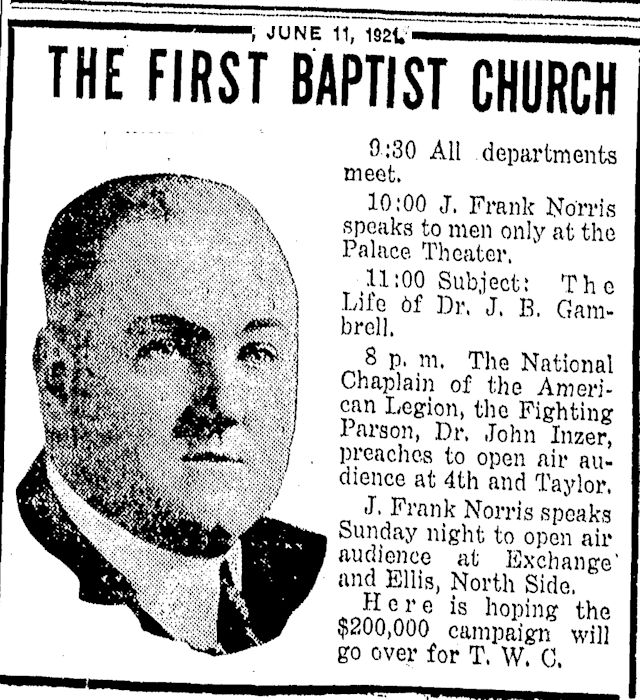

Theaters are dark in the mornings. So, the Palace booked J. Frank Norris, who often addressed men-only audiences.

Theaters are dark in the mornings. So, the Palace booked J. Frank Norris, who often addressed men-only audiences.

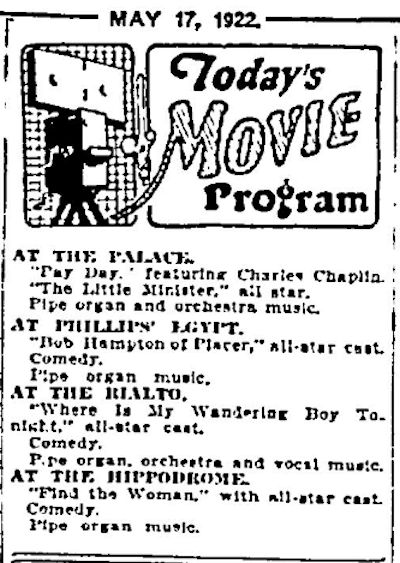

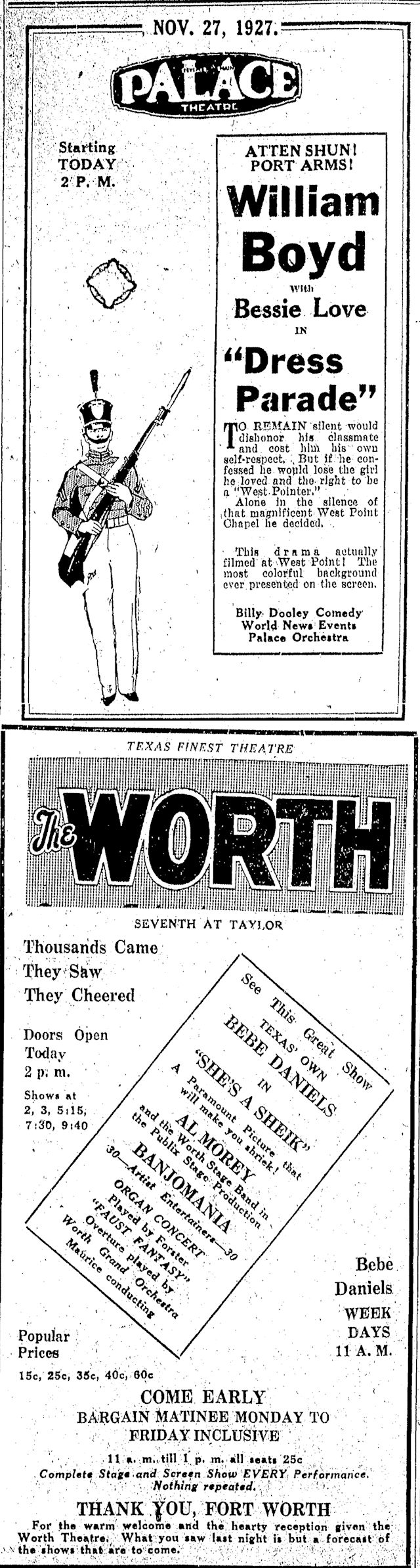

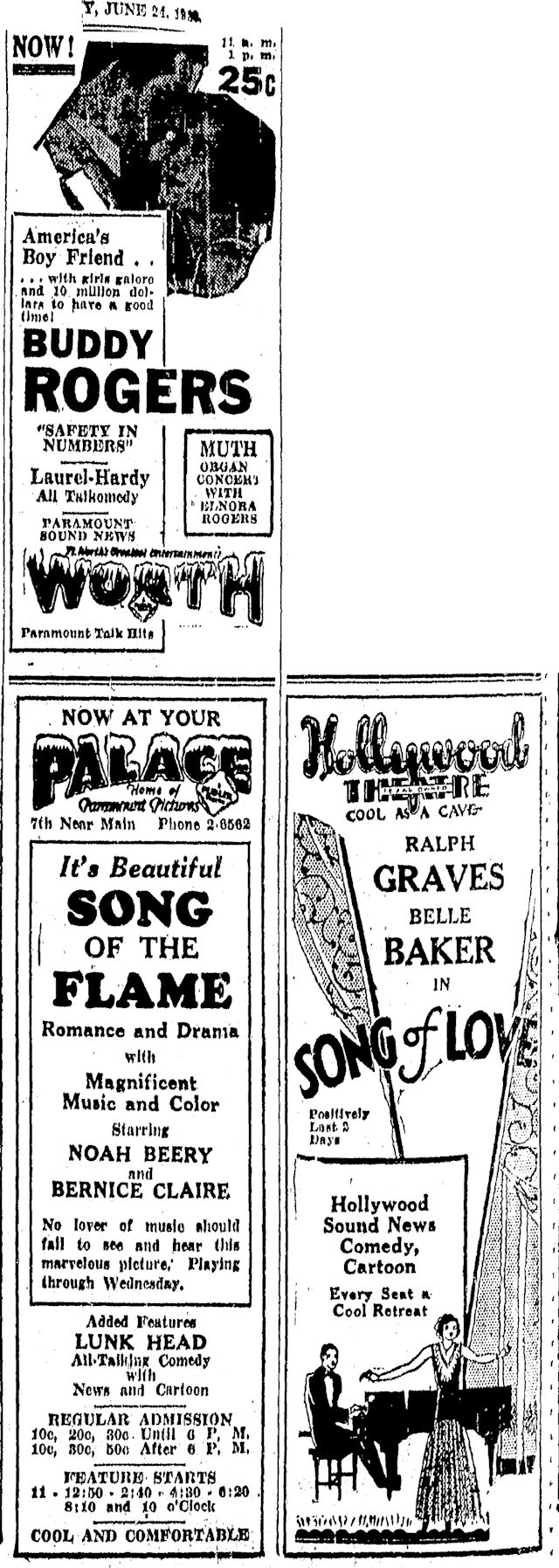

Note that each film theater also presented organ music. The organist performed between movies or live performances and also provided the background music for the silent movies being shown.

Note that each film theater also presented organ music. The organist performed between movies or live performances and also provided the background music for the silent movies being shown.

In 1927 the Palace got some competition on 7th Street as the Worth Theater opened.

In 1927 the Palace got some competition on 7th Street as the Worth Theater opened.

Three years later Show Row got its third and last member as the Hollywood Theater opened.

Three years later Show Row got its third and last member as the Hollywood Theater opened.

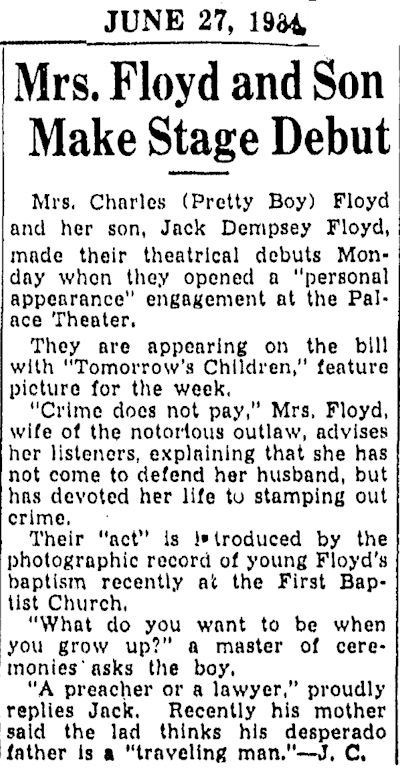

The wife and son of bank robber Charles (“Pretty Boy”) Floyd appeared at the Palace in 1934 to remind their audience that “crime does not pay.”

The wife and son of bank robber Charles (“Pretty Boy”) Floyd appeared at the Palace in 1934 to remind their audience that “crime does not pay.”

(Pretty Boy Floyd would probably agree with claim on October 22 when police and FBI agents led by Melvin Purvis closed in on him in a cornfield in East Liverpool, Ohio.)

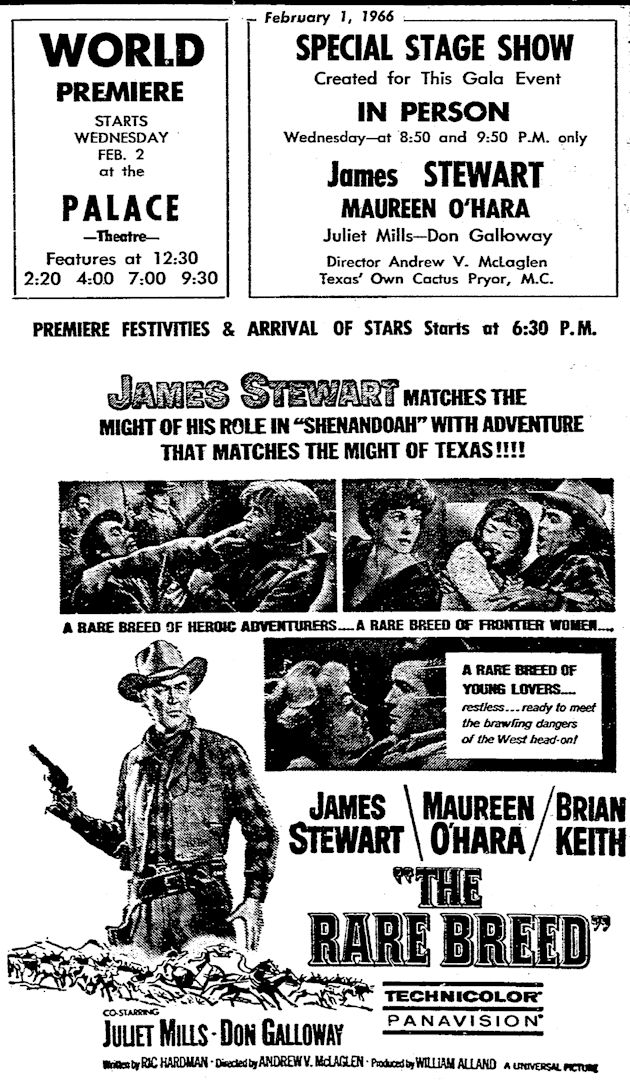

Jimmy Stewart and Maureen O’Hara made a personal appearance at the Palace in 1966 to promote The Rare Breed.

Jimmy Stewart and Maureen O’Hara made a personal appearance at the Palace in 1966 to promote The Rare Breed.

But then came the 1970s, and that decade was not kind to the Palace or, indeed, to all of Show Row.

The Worth Theater closed in 1971, was demolished in 1972.

In 1976 the Hollywood Theater closed. (Some of the theater survives within the repurposed building.)

In 1974 local businessman John O’Hara bought the Palace from the ABC Interstate Theaters chain, which had planned to close the theater. He hoped to keep the projectors turning, showing classic movies.

In 1974 local businessman John O’Hara bought the Palace from the ABC Interstate Theaters chain, which had planned to close the theater. He hoped to keep the projectors turning, showing classic movies.

But for the Palace, Elston Brooks wrote, The Big Sleep, starring Bogie and Bacall, was the last picture show. The theater closed in November 1974.

But for the Palace, Elston Brooks wrote, The Big Sleep, starring Bogie and Bacall, was the last picture show. The theater closed in November 1974.

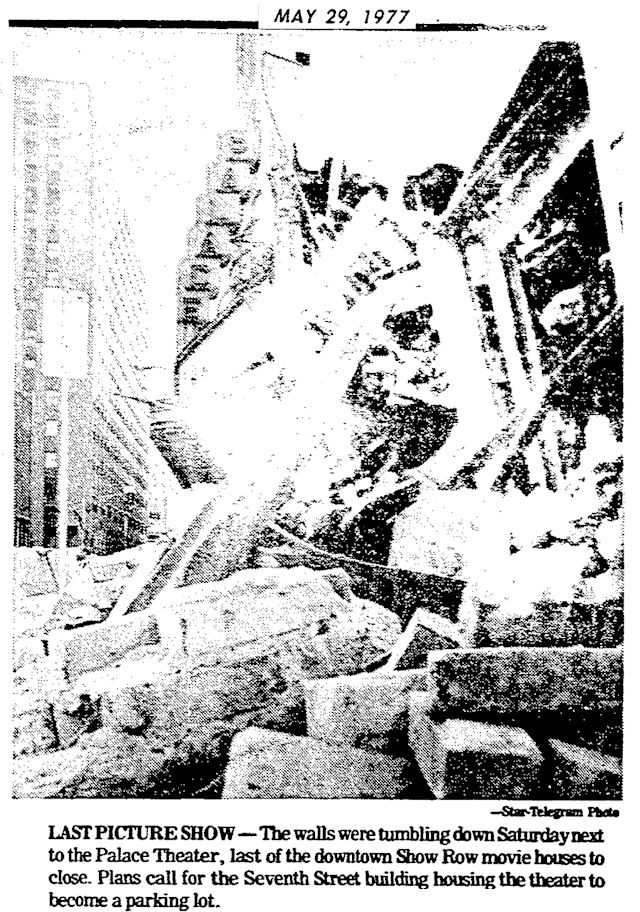

The Palace Theater was torn down in 1977, replaced by a parking lot.

The Palace Theater was torn down in 1977, replaced by a parking lot.

This 1945 photo shows the Aviation Building dwarfing the Palace Theater. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Libraries W. D. Smith Commercial Photography Collection.)

Since 1930 the Palace’s neighbor to the west had been the nineteen-story art deco Aviation Building, designed by Wyatt Hedrick. The building opened as the home of American Airlines and was built by A. P. Barrett.

Since 1930 the Palace’s neighbor to the west had been the nineteen-story art deco Aviation Building, designed by Wyatt Hedrick. The building opened as the home of American Airlines and was built by A. P. Barrett.

The Aviation Building (later named “Trans-American Life Building”) was torn down in 1978, replaced by a drive-through bank facility.

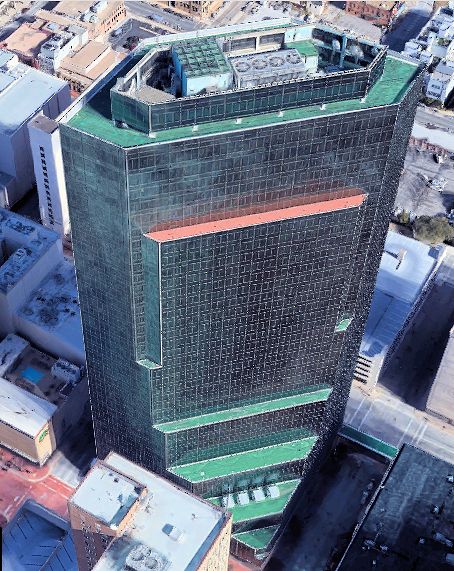

In 1982 the Aviation Building and Palace Theater lots yielded to the forty-story Carter-Burgess Plaza building (now the UMB Bank Building).

In 1982 the Aviation Building and Palace Theater lots yielded to the forty-story Carter-Burgess Plaza building (now the UMB Bank Building).

The End

Please file out of the theater in an orderly fashion. Good night, and drive safely.

“But wait, Hometown!” I hear you say. “What about the Palace Theater’s famous lightbulb?”

Ah, you remembered. Follow the usher to Part 2:

The Palace Theater (Part 2): Burn Brightly, Eternal Light

Fort Worth’s Street Gang

Posts About Cinema in Cowtown