Every year in the life of a big city is filled with news. Of course, current events aside, the year 1949 had been destined to be newsworthy for Fort Worth way back on June 6, 1849 when Major Ripley Arnold had raised the U.S. flag over the Army’s new Fort Worth.

On October 30, 1949 the Star-Telegram commemorated Cowtown’s centennial year with a 480-page special edition.

On October 30, 1949 the Star-Telegram commemorated Cowtown’s centennial year with a 480-page special edition.

Elsewhere during the year 1949 in Fort Worth, on March 2 Lucky Lady II, a B-50 stationed at Carswell Air Force Base, landed after completing the world’s first around-the-world nonstop flight. Also in March, William Knox Gordon, the man who coaxed coal, shale, and oil out of the earth, died.

On April 2 WBAP-TV broadcast the first baseball game in the Southwest: the Fort Worth Cats versus the Brooklyn Dodgers at LaGrave Field. The Dodgers won 9-3. Jackie Robinson hit a triple.

On May 15 LaGrave Field was destroyed by fire.

Two days later ten people died in the worst flood in Fort Worth history.

On September 15 five crew members were killed when their B-36 crashed at Carswell.

In October, William J. Bailey, the man who built both a vaudeville theater and a cemetery, died.

In December Bob Hope played in a charity golf match at River Crest Country Club.

Amid those news events of 1949 two crimes made the front pages locally and even from coast to coast.

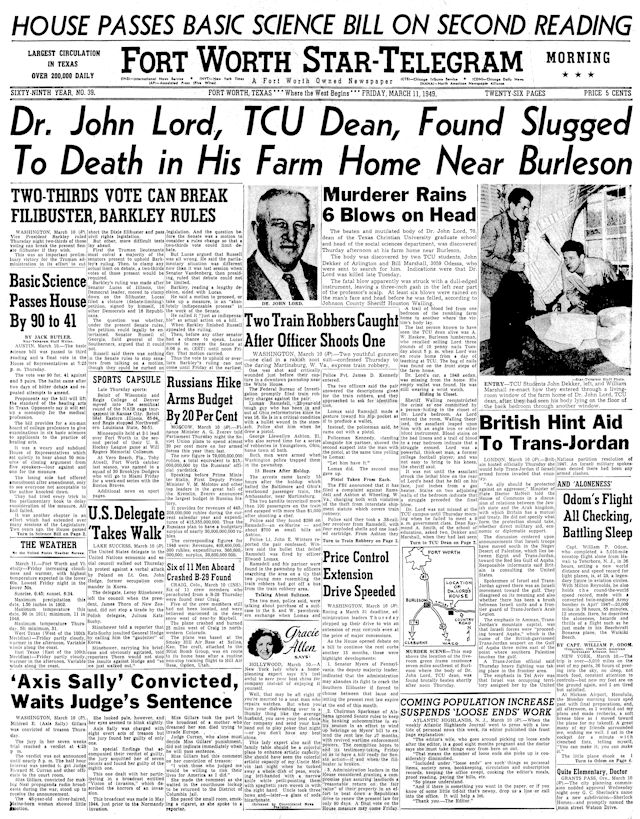

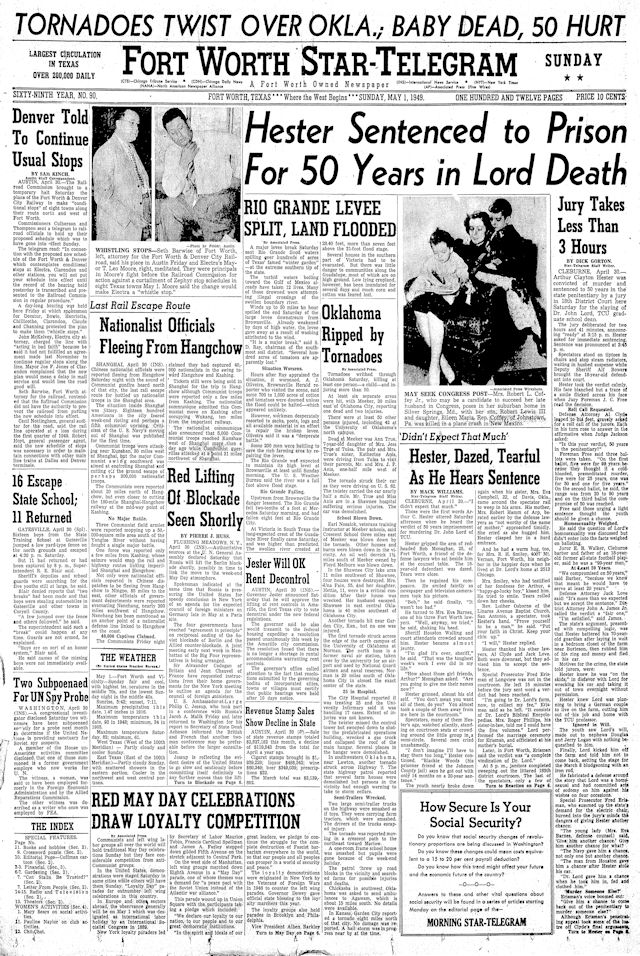

On March 10 the badly beaten body of Dr. John Lord, seventy, was found in his farmhouse in Johnson County. Lord—dean of TCU’s graduate school and head of the social sciences department—had taught at TCU thirty years.

On March 10 the badly beaten body of Dr. John Lord, seventy, was found in his farmhouse in Johnson County. Lord—dean of TCU’s graduate school and head of the social sciences department—had taught at TCU thirty years.

The story was on front pages from coast to coast.

The story was on front pages from coast to coast.

Johnson County Sheriff Houston Walling said Lord had been hit on the head and face at least six times with an angle iron or other blunt instrument, probably wielded by an assailant who had sprung from a bedroom closet. Lord’s wallet was empty. A wedding band and his automobile were missing.

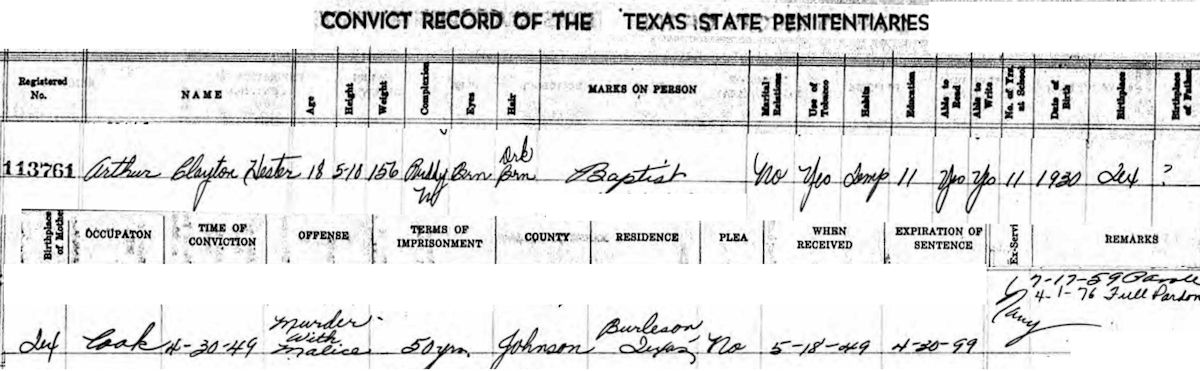

Suspicion fell upon Lord’s ward, Arthur Clayton Hester, eighteen.

Suspicion fell upon Lord’s ward, Arthur Clayton Hester, eighteen.

Hester, who walked with a slight limp after contracting polio at age eight, as a youth had been placed in an orphanage by his mother. Leaving the orphanage and homeless in 1945, he was walking down Chicago Street in Meadowbrook when he saw Lord working in his garden. Hester asked Lord for a meal. Lord took the boy in, became his guardian, enrolled him at Poly High School. Hester soon enlisted in the Navy, and Lord moved from Meadowbrook to the Johnson County farm. Hester was dishonorably discharged from the Navy for overstaying furloughs. He returned to Lord to live at the farm, where Hester worked as cook and driver.

When Lord’s body was found on March 10, 1949, Hester was missing. Hester was charged with murder.

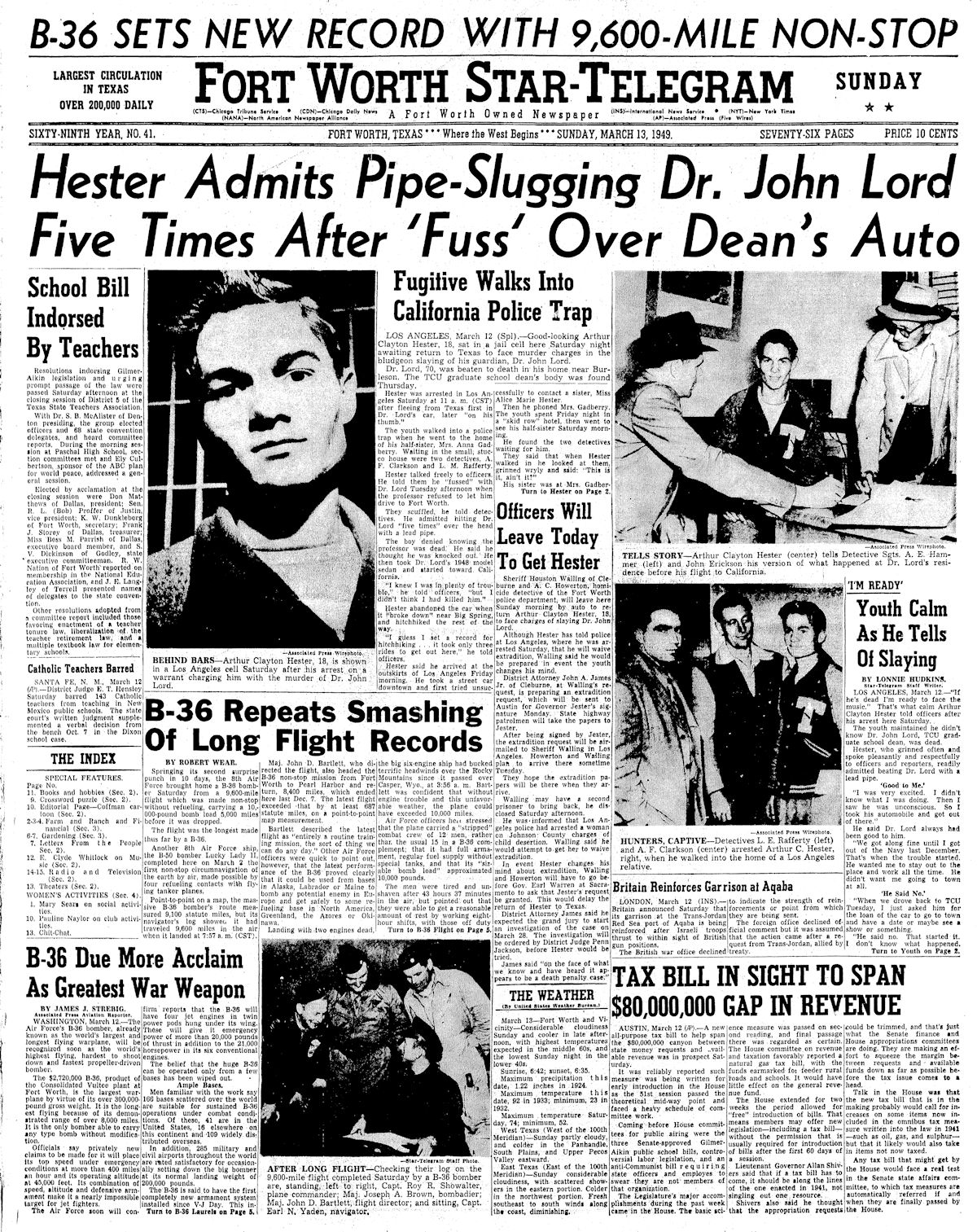

After Lord’s car was found east of Big Spring, police suspected that Hester was hitchhiking to California to stay with his sister. Two Los Angeles police officers were waiting for Hester when he arrived at his sister’s home. He was arrested and brought back to Cleburne to be jailed.

After Lord’s car was found east of Big Spring, police suspected that Hester was hitchhiking to California to stay with his sister. Two Los Angeles police officers were waiting for Hester when he arrived at his sister’s home. He was arrested and brought back to Cleburne to be jailed.

Hester confessed to hitting Lord with a lead pipe after the two argued because Hester without Lord’s permission had driven Lord’s car to Waco to visit a girlfriend.

Hester claimed that when he had fled the scene he did not know that Lord had been killed.

Hester told police that he and Lord had argued often since their reunion. He blamed his “restlessness” on his dishonorable discharge.

Meanwhile, flags were lowered to half staff at TCU, and classes were suspended for two hours for his funeral.

Hester later led police to the Fort Worth pawn shop where he had been paid $4 for the wedding band he had taken from Lord’s finger.

Hester also was questioned for two hours by a psychiatrist.

“The doctor asked me if I liked girls, and I replied that I do,” Hester told the Star-Telegram. “He also wanted to know if I had a conscience and seemed very annoyed when I answered yes. When he asked me if I thought I was insane, I said no. I asked him if he thought he was crazy.”

Hester’s mother, Mrs. Maggie Hamm of Arp, said, “I never could help him much after his daddy, John, died when he was two. I had to put him and his two sisters in orphanages because I couldn’t support them.”

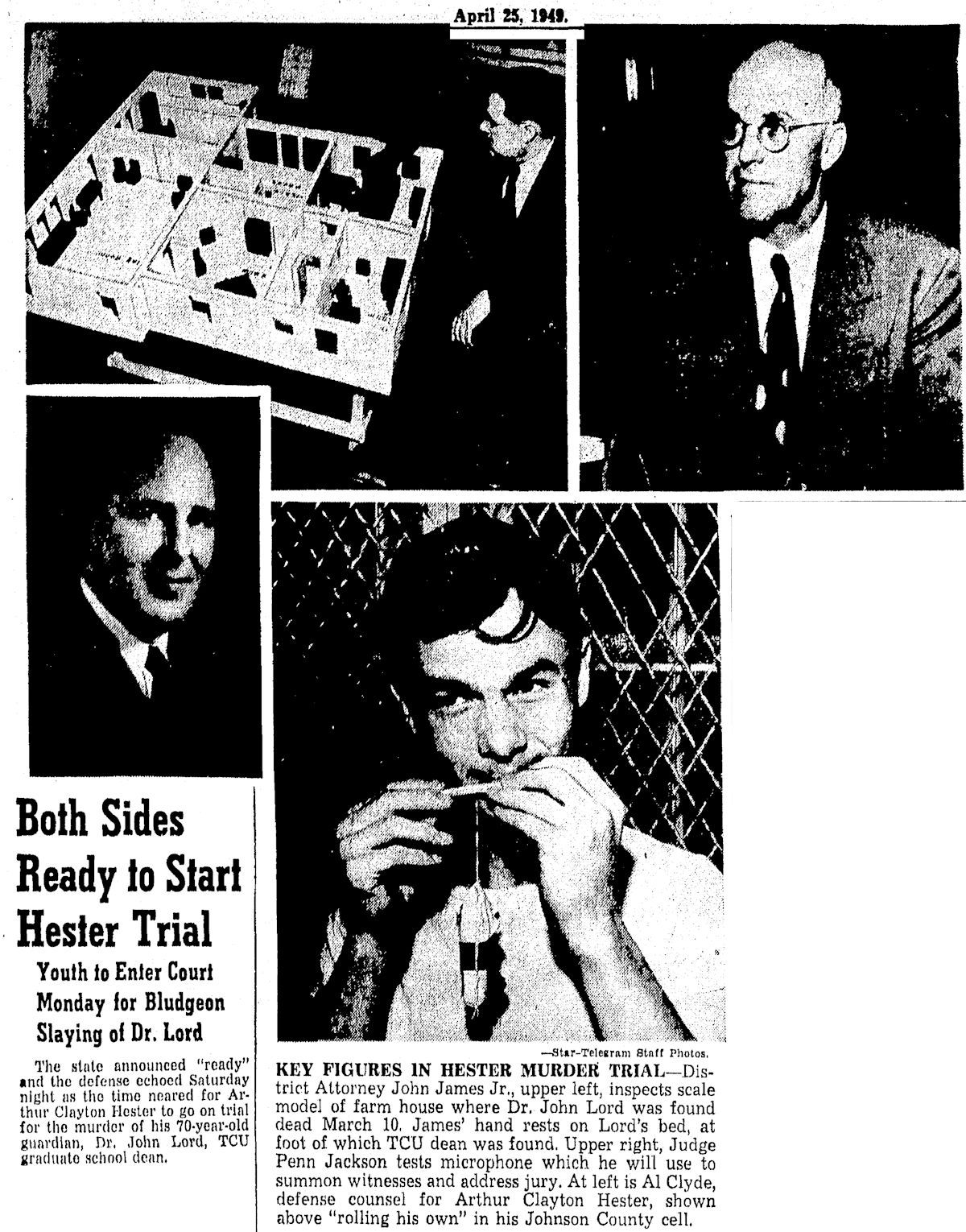

Hester’s trial began on April 26. The state sought the death penalty for murder with malice.

Hester’s trial began on April 26. The state sought the death penalty for murder with malice.

Hester’s defense counsel did not deny that Hester attacked Lord with an iron pipe. The defense contended that Hester did not mean to kill Lord and that the state could not prove that Hester’s assault was the cause of death because the state had failed to order an autopsy.

Motives for the murder, the state told jurors, were:

Hester knew he was in disfavor with Lord for wrecking his car and driving it out of town without permission.

Hester knew Lord was planning to bring in a German couple to live on the farm, denying Hester of his job and home with Lord.

Hester had seen Lord’s will naming two nephews as heirs, with no mention of Hester.

Finally, Lord had evicted Hester from the farm and told him not to come back.

Hester testified that Lord had sexually assaulted him at least four times. Hester later recanted that testimony, signing a statement in which he said, “Dr. John Lord did not at any time ever make an unnatural sex advance toward me.”

He later recanted his recantation by stating that “he [Lord] was a homosexual and I said he wasn’t because I thought it would give me less time at the pen. . . . I got the idea that if I tried to clear Dr. Lord’s name, it would help me out in Huntsville.”

Special prosecutor Fred Erisman of Longview, who summed up the state’s demand for the electric chair, stressed to the jury the dangers of giving Hester a second chance: “The young lady [defense counsel Eva Barnes, who would become Tarrant County’s first woman judge] said, ‘Give him another chance.’ Give him another chance for what? Dr. Lord gave him a chance when he took him in, fed and clothed him. Give him a chance to come back out of the penitentiary to murder someone.”

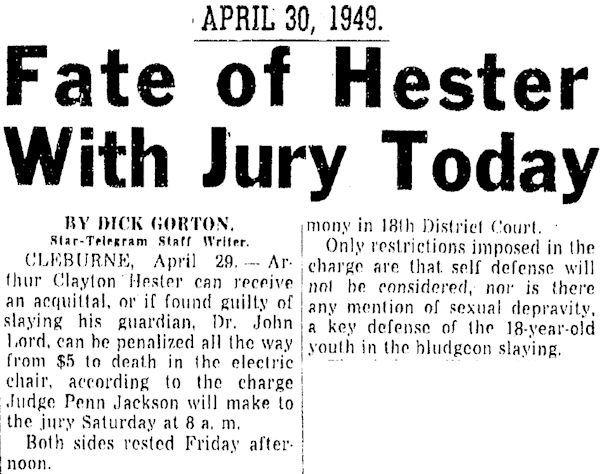

The judge’s instructions to the jury included a wide range of possible punishments: from a $5 fine (simple assault) to execution in the electric chair (murder with malice).

The judge’s instructions to the jury included a wide range of possible punishments: from a $5 fine (simple assault) to execution in the electric chair (murder with malice).

Erisman left the courthouse before the jury reached a verdict.

“I’m going to Dr. Lord’s farm now to collect my fee,” Erisman said as he left. “It consists of Dr. Lord’s Biblical Encyclopedias. Mrs. Roger Phillips, his sister-in-law, told me I could have the five volumes.”

Lord had performed the marriage ceremony for Erisman and had officiated at his mother’s burial.

The jury deliberated less than three hours before delivering a sentence of fifty years in prison.

The jury deliberated less than three hours before delivering a sentence of fifty years in prison.

The jury foreman said jurors had advocated sentences ranging from five to ninety-nine years. On the third ballot they compromised on fifty years.

One juror said jurors compromised on fifty years because that sentence assured that Hester would serve at least twenty years.

Hester was not so sure: “I don’t imagine I’ll have to stay there too long,” Hester told the Star-Telegram. “Blackie Woods [a Johnson County jail cellmate] says he got out with only fourteen months on a twenty-year sentence.”

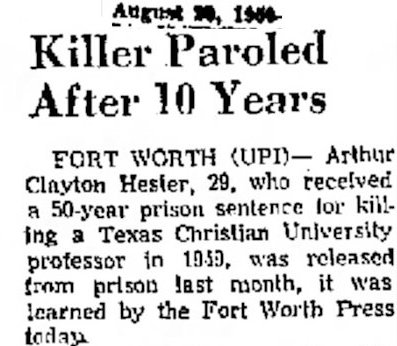

And Hester was right. In 1959 he was paroled after ten years.

And Hester was right. In 1959 he was paroled after ten years.

According to his prison record, Hester received a full pardon on April 1, 1976.

According to his prison record, Hester received a full pardon on April 1, 1976.

Arthur Clayton Hester died in 1986 and is buried next to his wife in Rusk, Texas.

Arthur Clayton Hester died in 1986 and is buried next to his wife in Rusk, Texas.

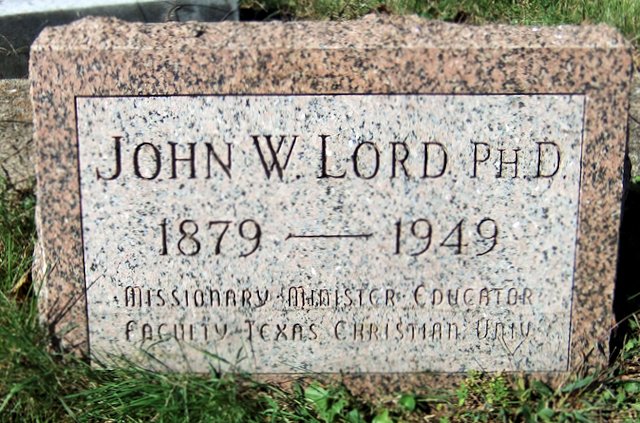

Dr. John W. Lord is buried next to his wife in Kentucky.

Dr. John W. Lord is buried next to his wife in Kentucky.

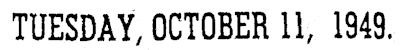

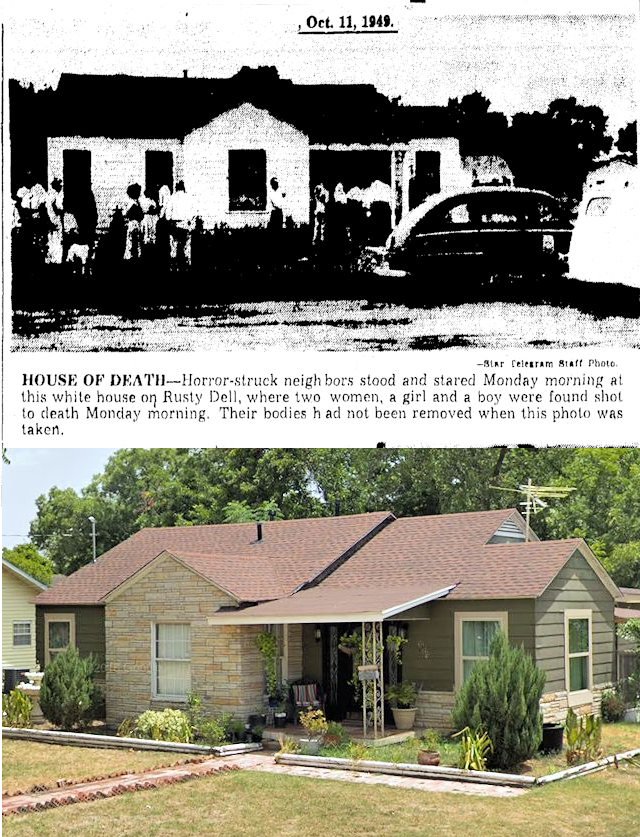

On the morning of Monday, October 10, Mrs. T. C. Hukill of 3816 Rusty Dell in Riverside was surprised when the two children of next-door neighbors Richard G. and Elizabeth Finch did not appear for their ride to school. Mrs. Hukill customarily gave Penelope and Richard Allan Finch a ride when she drove her daughter to Springdale Elementary School.

On the morning of Monday, October 10, Mrs. T. C. Hukill of 3816 Rusty Dell in Riverside was surprised when the two children of next-door neighbors Richard G. and Elizabeth Finch did not appear for their ride to school. Mrs. Hukill customarily gave Penelope and Richard Allan Finch a ride when she drove her daughter to Springdale Elementary School.

Later that morning Mrs. Hukill telephoned the Finch house but got no answer. She went next door, knocked on the front and rear doors. Then she began peering in windows. She saw the body of Mrs. Finch’s mother, Mrs. Edith Walker, on her bedroom floor.

Police were called.

The four occupants of the house—Mrs. Finch, thirty-three; daughter Penelope, eight; son Richard Allan, seven; and Mrs. Walker, about sixty-five—were found dead in their bedrooms.

The four occupants of the house—Mrs. Finch, thirty-three; daughter Penelope, eight; son Richard Allan, seven; and Mrs. Walker, about sixty-five—were found dead in their bedrooms.

All four had been shot in the head.

A .22-caliber pistol was found three inches from the right hand of Mrs. Walker.

Neighbors said they had last seen Mrs. Finch and her children Saturday night.

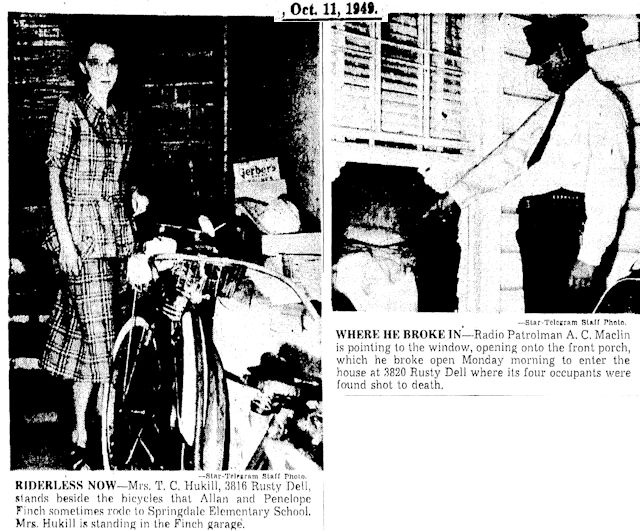

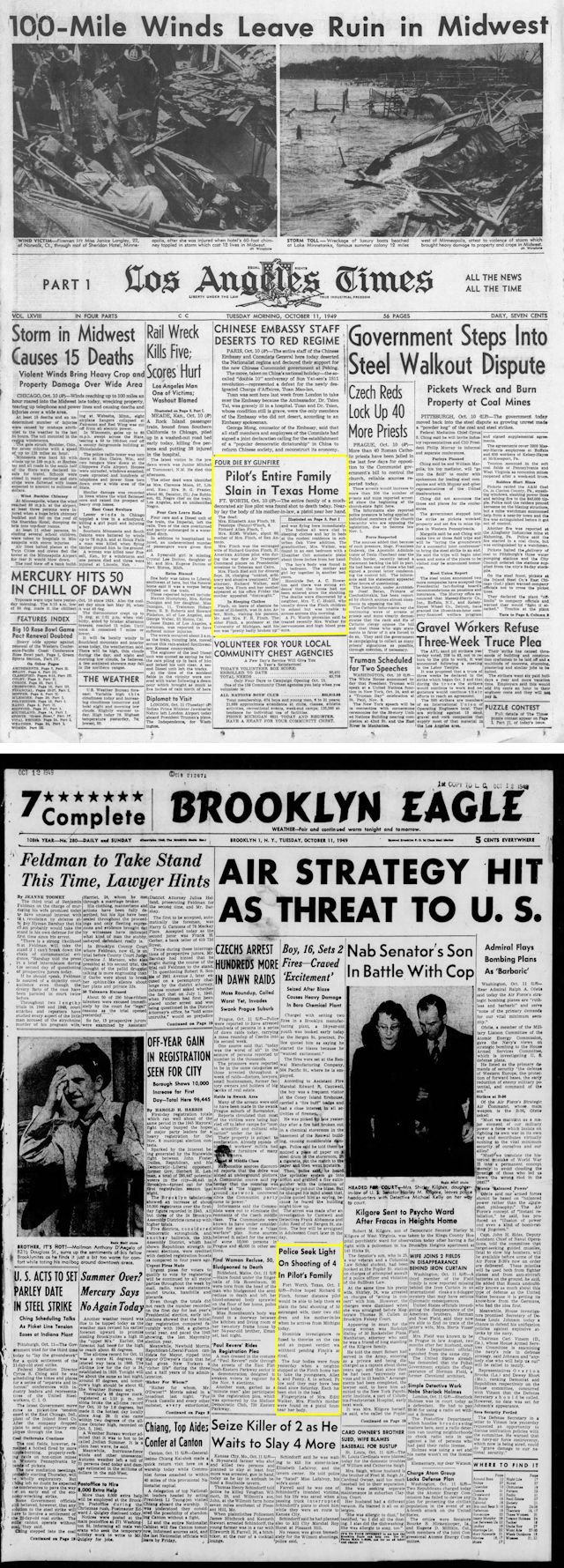

The story was news from coast to coast.

The story was news from coast to coast.

Mr. and Mrs. Finch had been estranged since June. Mr. Finch, thirty-seven, was an American Airlines pilot. He had suffered from an allergy and asthma since serving in north Africa as an Air Force colonel during World War II and was on a two-year leave of absence from American Airlines.

Mr. and Mrs. Finch had been estranged since June. Mr. Finch, thirty-seven, was an American Airlines pilot. He had suffered from an allergy and asthma since serving in north Africa as an Air Force colonel during World War II and was on a two-year leave of absence from American Airlines.

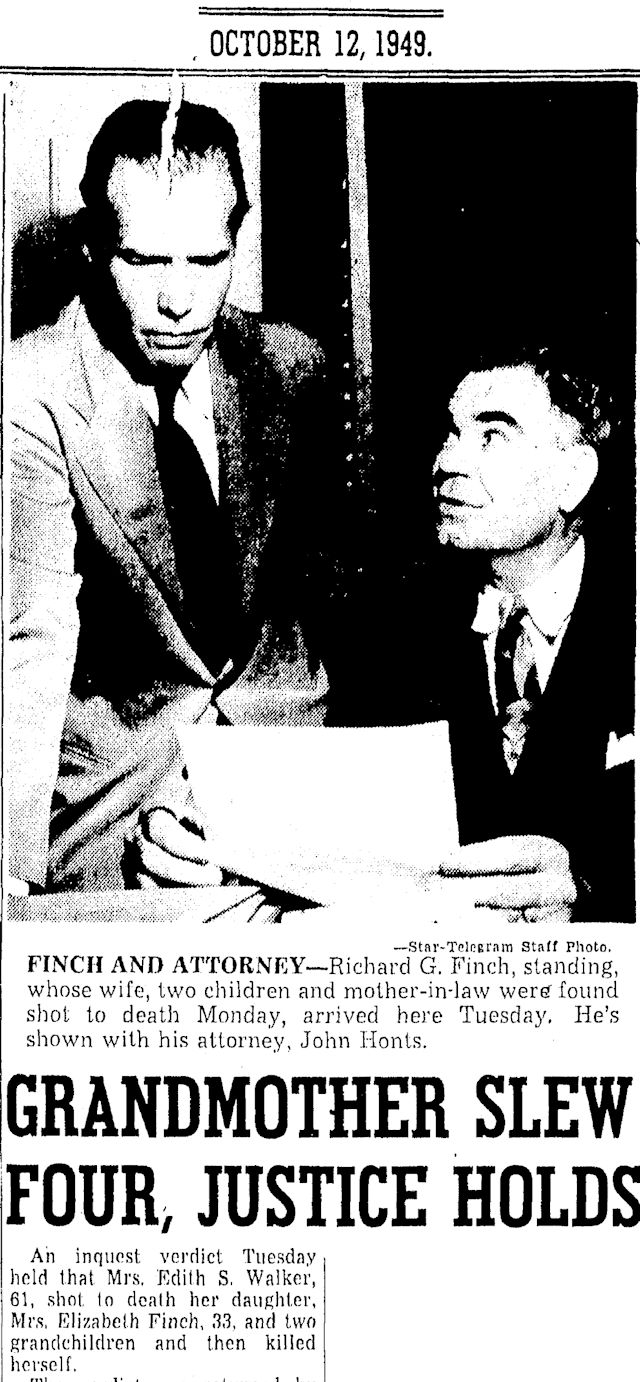

Mr. Finch was visiting his parents in Michigan when notified of the four deaths.

He returned to Fort Worth the day after the bodies were found.

The Star-Telegram reported that Mrs. Walker had moved in with the Finches that summer. Mr. Finch had said at the time that it “wouldn’t work out” and had suggested she instead live with her sons.

Soon after, Mr. and Mrs. Finch separated. In September Mrs. Finch filed a petition for divorce, charging Mr. Finch with mental cruelty and “unkind, arbitrary, and abusive treatment.”

But on October 7 Mrs. Finch, accompanied by her mother, had told her attorney that she wanted the petition for divorce to be dismissed.

Four days later she was found dead.

For all its tragedy and the front-page headlines, the Finch case, like the Lord case, presented little whodunit suspense. The crime weapon was found near Mrs. Walker’s hand and had her fingerprints on it. The house showed no sign of forced entry. Nothing was missing to indicate robbery.

For all its tragedy and the front-page headlines, the Finch case, like the Lord case, presented little whodunit suspense. The crime weapon was found near Mrs. Walker’s hand and had her fingerprints on it. The house showed no sign of forced entry. Nothing was missing to indicate robbery.

The day after the bodies were found, a justice of the peace ruled that Mrs. Walker had killed her daughter and two grandchildren and then killed herself.

Mrs. Finch’s attorney later told police that Mrs. Walker had seemed “distraught” when her daughter had asked that the divorce petition be dismissed.

A Fort Worth physician had recently treated Mrs. Walker for nervousness.

Mr. Finch said he had been unaware that his wife had asked that her divorce petition be dismissed.

“If I had [known], I would have been back here, and I might have stopped this thing. If this suit [petition] was actually withdrawn, I know it precipitated the shooting. I wish they had wired me.”

On October 26 Judge Renfro in 96th District Court dismissed the divorce petition of Mrs. Finch, as she had requested four days before she, her two children, and mother were found dead.

On October 26 Judge Renfro in 96th District Court dismissed the divorce petition of Mrs. Finch, as she had requested four days before she, her two children, and mother were found dead.