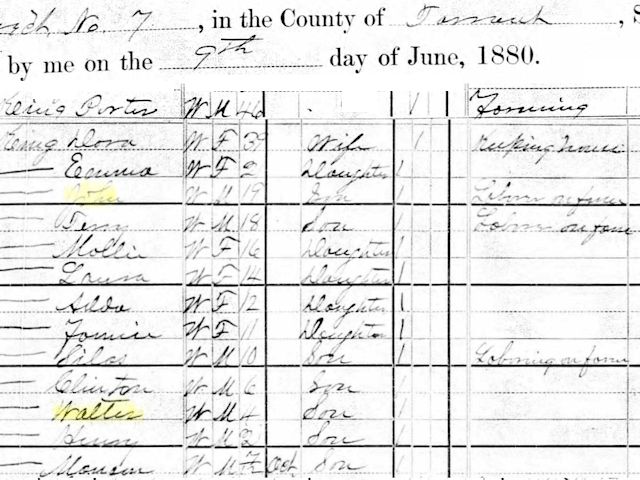

Walter G. King was born in 1876, one of twelve children of Porter and Dora King.

In 1880 the children ranged in age from nineteen years (son John P.) to seven months (son Manson). Walter was four, fifteen years younger than John.

In 1880 the children ranged in age from nineteen years (son John P.) to seven months (son Manson). Walter was four, fifteen years younger than John.

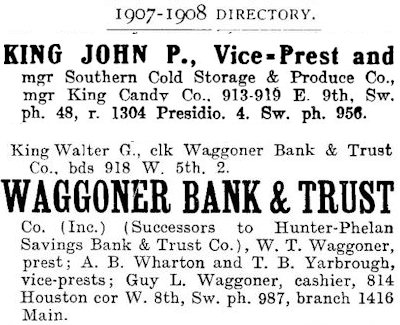

Fast-forward to 1907. John P. King had grown up to become the candyman: manager of King Candy Company. Brother Walter was a clerk at Waggoner Bank & Trust. President of the bank was cowman capitalist W. T. Waggoner. One of the vice presidents was Waggoner’s son-in-law, A. B. Wharton of today’s Thistle Hill.

Fast-forward to 1907. John P. King had grown up to become the candyman: manager of King Candy Company. Brother Walter was a clerk at Waggoner Bank & Trust. President of the bank was cowman capitalist W. T. Waggoner. One of the vice presidents was Waggoner’s son-in-law, A. B. Wharton of today’s Thistle Hill.

But that year Waggoner opened a branch bank on Main Street, and Walter King was named assistant cashier in charge of the new branch.

But that year Waggoner opened a branch bank on Main Street, and Walter King was named assistant cashier in charge of the new branch.

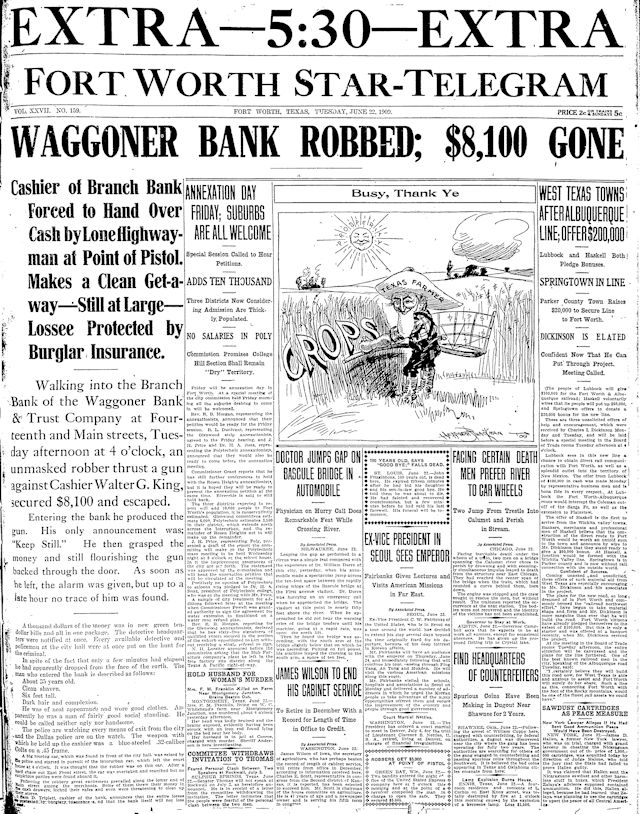

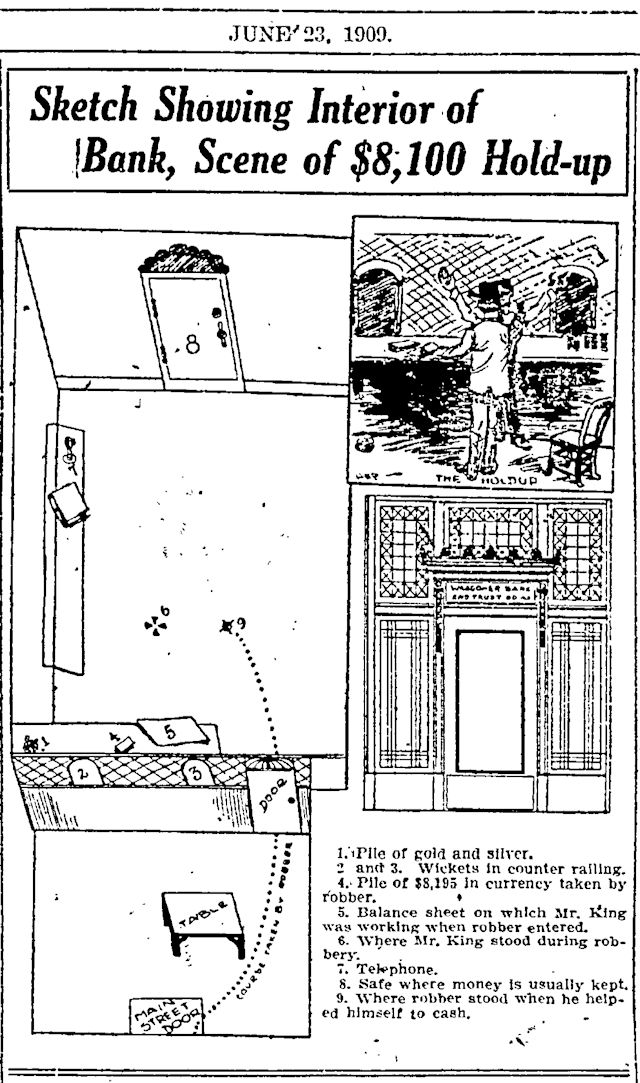

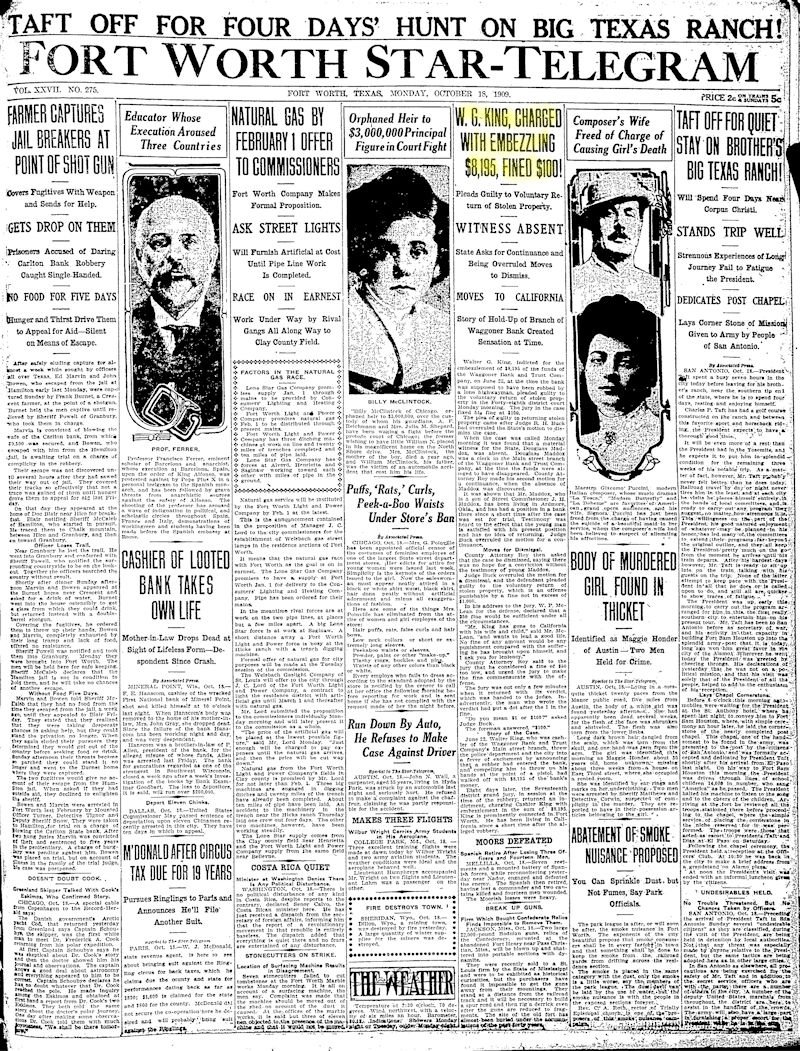

Fast-forward two years. At 4:05 p.m. on June 22, 1909, the Star-Telegram reported in an extra edition just eighty-five minutes later, a “lone highwayman” armed with a 32-caliber pistol entered the branch bank, walked to a wicket, and confronted cashier King, who was on the other side of the counter counting money.

Fast-forward two years. At 4:05 p.m. on June 22, 1909, the Star-Telegram reported in an extra edition just eighty-five minutes later, a “lone highwayman” armed with a 32-caliber pistol entered the branch bank, walked to a wicket, and confronted cashier King, who was on the other side of the counter counting money.

“Keep still,” the highwayman said to King. The Dallas Morning News wrote that King had “the muzzle of a six-shooter . . . pushed under his nose.”

The Star-Telegram wrote: “The robber was quiet and businesslike. . . . There was no order of ‘hands up,’ no blood-curdling threats, and no picturesque actions.”

The robber then walked past the counter to where King—and the money—was.

The robber took $8,195 ($231,000 today) in currency that was stacked on the counter.

Also on the counter was a thousand dollars in gold and silver, which the robber did not take.

The robber’s timing was impeccable. King was the only employee in the bank at the time after business hours. The money was in plain sight on the counter. And if the robber had entered the bank a minute or two later, the money would have been safely locked in the vault. The bank also had more than the usual amount of cash on hand because June 22 was close to payday for workers of the nearby Texas & Pacific and Fort Worth & Denver City railroads.

The robber also knew where the bank cashier kept his own weapon: The Dallas Morning News reported that the robber, even before reaching for the money on the counter, reached beneath the counter and took the cashier’s pistol.

What the robber did not take was the gold and silver. The Star-Telegram theorized that he “did not wish to be hindered by weight in his flight.”

The robber quietly backed out the front door of the bank.

By the time King reached the front door, he later told police, the robber was nowhere to be seen. The robber blended in with other pedestrians on the crowded sidewalk and, the Star-Telegram wrote, “had apparently dropped from the face of the earth.”

King phoned the main Waggoner bank and the police.

King gave police a detailed description of the robber: about thirty-five years old, clean shaven, six feet tall, dark hair and complexion, neat appearance, good clothes.

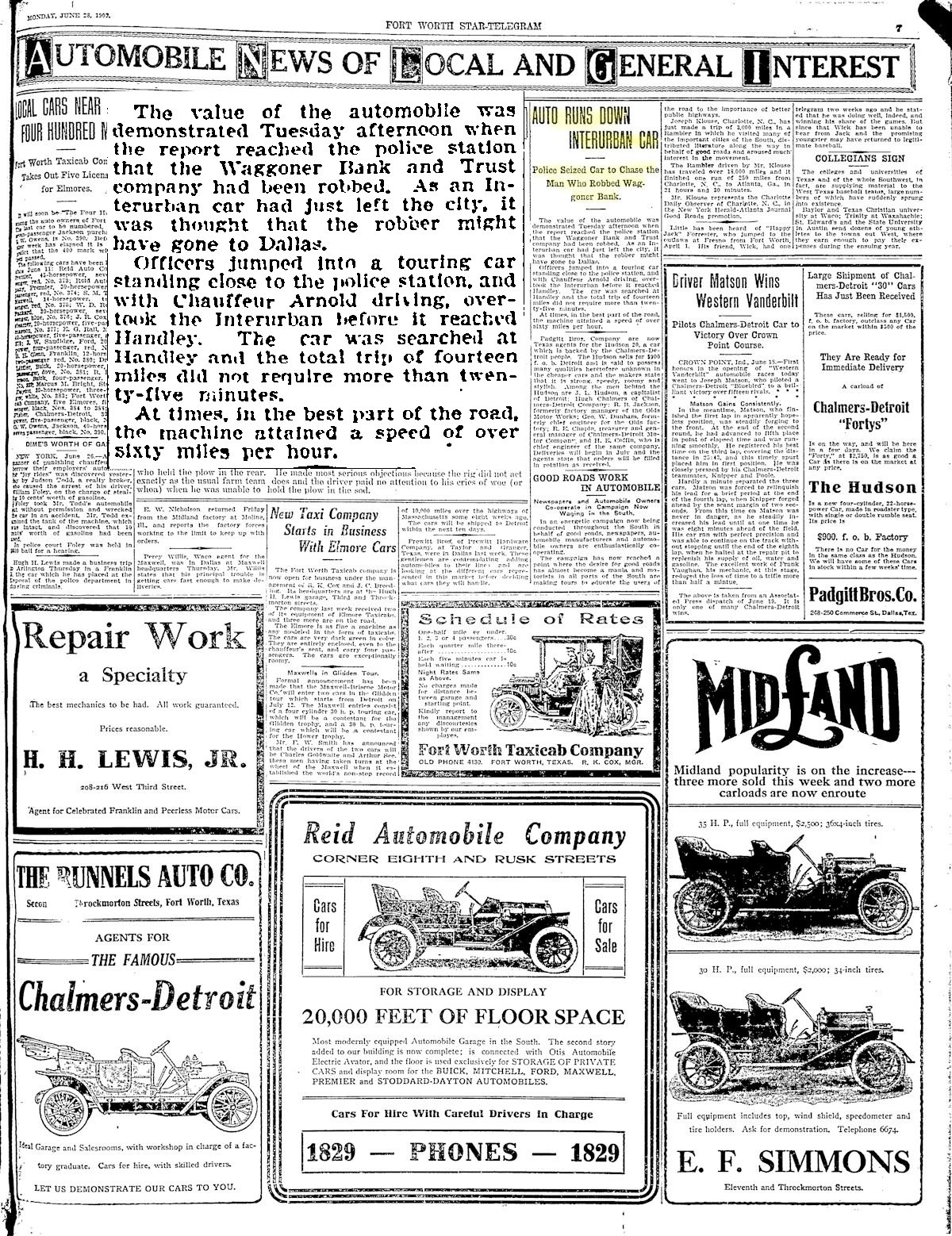

The robbery was one of the first crimes in Fort Worth in which police relied on the automobile in their investigation. In 1909, the Star-Telegram reported in a sidebar on the robbery, only 390 automobiles were registered in the city. (Fort Worth’s population in 1910 would be 73,312, so 390 automobiles is about one per 188 people.)

The robbery was one of the first crimes in Fort Worth in which police relied on the automobile in their investigation. In 1909, the Star-Telegram reported in a sidebar on the robbery, only 390 automobiles were registered in the city. (Fort Worth’s population in 1910 would be 73,312, so 390 automobiles is about one per 188 people.)

After cashier King gave the alarm, Mayor William D. Davis and former Police Chief James H. Maddox arrived at the branch bank in Davis’s new seven-seat Empire automobile. Davis later lent his car to Fire and Police Commissioner George Mulkey for use in the investigation.

Davis had made news on his first day in office on June 2 because he drove his “famous motor car” as he toured the various sites of municipal government.

Even the mere presence of an automobile was noteworthy in 1909. Witnesses told police that they had seen an automobile “waiting” at a corner a half-block from the branch bank “a few minutes before the robbery. . . . A few minutes later the auto was gone.”

After police were told that an interurban trolley bound for Dallas had passed the branch bank on Main Street shortly after the robbery, officers commandeered a “big touring car” that was parked near the police station and ordered the chauffeur to follow that trolley. With the chauffeur at the wheel, the trip of fourteen miles along the unpaved wagon road to Dallas “did not require more than twenty-five minutes,” and “at times . . . the machine attained a speed of over sixty miles per hour.”

Meanwhile bank vice president Tom Yarborough, another early autoist, also had pursued the interurban trolley in his car. He reached the trolley before the police did and halted it this side of Handley.

Yarborough was searching the interurban cars when police and their chauffeur arrived.

No robber was found, but the chauffeur had a tale to tell at dinner that night.

The robbery was reported in the New York Times.

The robbery was reported in the New York Times.

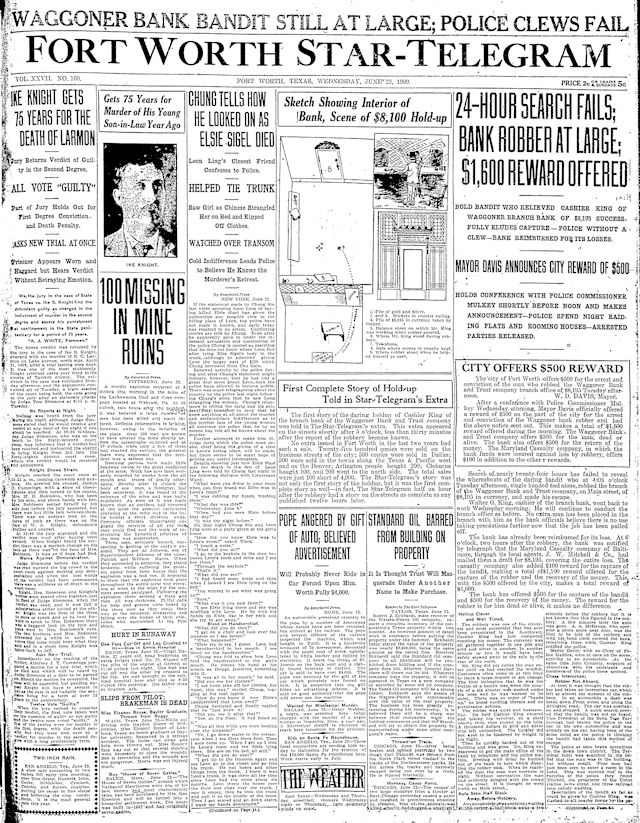

Cashier King returned to work the next day as the Star-Telegram reported “Police Without a Clew.”

Cashier King returned to work the next day as the Star-Telegram reported “Police Without a Clew.”

Police had spent the night raiding and rousting as they searched for the robber. Police searched the nearby Terminal Hotel and rooming houses. Men were arrested but soon released. Most of them were railroad men who boarded near the rail yards between runs.

As police beat the bushes, helpful citizens came forward. For example, Ed Pennington, ticket agent for the Houston & Texas Central railroad, offered police a possible clue: Just after the robbery a stranger “rushed” into the H&TC office in the Worth Hotel on Main Street and “flashed a roll of big bills.” The stranger bought a ticket to Mobile, Alabama without even asking the price. Pennington said the stranger hadn’t been seen since.

Within two hours of the robbery, the bank’s insurance company had reimbursed the bank for the loss.

Now, after police had spent a full day searching in vain for the robber, the Waggoner bank, its insurance company, and even the city offered rewards totaling $1,600 ($45,000 today) for both the return of the money and the apprehension—dead or alive—of the robber.

“The robbery was one of the cleverest and most successful that has ever been perpetrated in the Southwest,” the Star-Telegram wrote.

Mayor Davis said, “The man who is desperate enough and cool enough to take such a step is the most dangerous man that there can be around.”

The Tarrant County grand jury, already in session when the robbery occurred, took up the case. Witnesses—including Chief of Police June Polk—came and went as rumors (the robber had been captured and had confessed) circulated and were denied by police and the bank.

Police were aided by two detectives working for the insurance company and one working for the Texas Bankers’ Association.

Four days passed. Each day the news was “no news” in the search for the robber.

Then, on July 1, after eight days of no news, the cold case got hot.

Then, on July 1, after eight days of no news, the cold case got hot.

And embarrassing.

Friends of cashier Walter King said he had notified bank officials that he had just set the time lock on the vault of the branch bank to open at a certain hour. He told bank officials that when they opened the vault at that hour, they would find the $8,195.

And voila! They did. The stolen money had been unstolen!

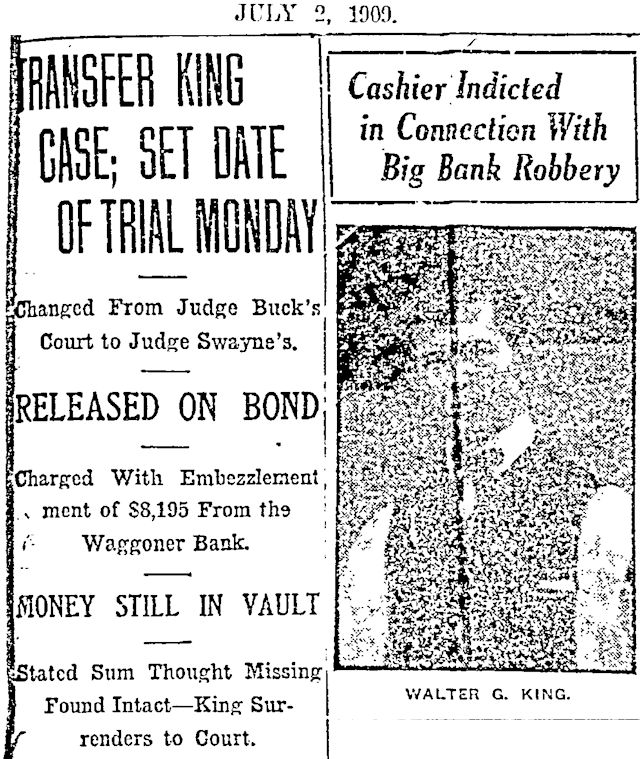

King was indicted for embezzlement of $8,195.

Signers of his $5,000 ($140,000 today) bond included his brother and Brown Harwood, a real estate dealer who would become the no. 2 man in the national Ku Klux Klan.

With the bank’s money returned and his freedom bought, just one thing remained on Walter King’s to-do list: move to California.

Fast-forward to October. When King’s case came to trial, the state could not produce a material witness. Douglas Maddox, son of James H. Maddox, former city marshal and deputy sheriff, had been a clerk at the branch bank under King. Douglas Maddox was now working at a bank in another city and said he did not wish to return to Fort Worth to testify against his former supervisor.

Well, all right then.

The state told the judge that without the testimony of Maddox it could not convict King of embezzlement.

The state asked that the trial be delayed.

The judge refused.

The state asked that the case be dismissed.

The judge refused.

But the judge did allow King to plead guilty to a charge of voluntary return of stolen money, a crime punishable by a fine of up to $1,000 ($28,000 today).

Defense attorney W. P. McLean Jr. told the jury, “Mr. King has gone to California with his wife and child and wants to lead a good life. No fine of any amount would be any punishment compared with the suffering he has brought upon himself.”

The jury fixed King’s fine at $100 ($3,000 today).

The jury fixed King’s fine at $100 ($3,000 today).

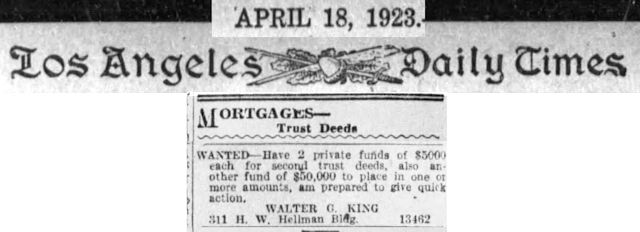

Apparently Walter G. King remained in California and remained in the financial industry.

Apparently Walter G. King remained in California and remained in the financial industry.