When you travel south on Main Street from Vickery Boulevard you ascend an incline, rising about forty feet during the 1,600 feet you travel before you begin to descend. You don’t notice the incline much in a car. But on a bicycle you notice.

After years of sweating and swearing my way up that incline I find that it has a name far more polite than the name I had been applying to it:

After years of sweating and swearing my way up that incline I find that it has a name far more polite than the name I had been applying to it:

“Tucker’s Hill.”

And therein lies some history.

And therein lies some history.

William Bonaparte Tucker (“Bony” to his friends) was born in Kentucky in 1824.

William Bonaparte Tucker (“Bony” to his friends) was born in Kentucky in 1824.

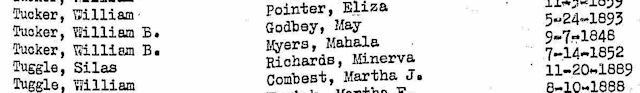

He was married in 1848 to Mahala Ann Myers.

He was married in 1848 to Mahala Ann Myers.

In 1850 Bony and Mahala were living in Casey County, Kentucky.

In 1850 Bony and Mahala were living in Casey County, Kentucky.

In 1853, the year the Army abandoned its Fort Worth, the couple moved to Fort Worth and settled four miles north of town. Later Major James Jones Jarvis would live nearby. Today that area is Jarvis Heights.

In 1853, the year the Army abandoned its Fort Worth, the couple moved to Fort Worth and settled four miles north of town. Later Major James Jones Jarvis would live nearby. Today that area is Jarvis Heights.

Tucker was among the founders of Fort Worth’s first Masonic lodge in 1854. He held the office of tiler (outer guard).

In the early days of Anglo settlement, Tucker “fought Indians on the present site of Fort Worth when white inhabitants west of the Sabine [River] were very few.”

Tucker was a farmer, like his father before him. But in 1856 he entered politics. He was elected county sheriff, replacing John B. York. In 1858 Tucker was elected district clerk.

In 1860 Tucker was among civic leaders who signed a bond assuring taxpayers that if Fort Worth was selected as county seat in the third Fort Worth-Birdville face-off, a county courthouse would be built in Fort Worth at no cost to taxpayers.

In 1862 Tucker was elected county judge and served until 1867, when he was forced out of office by a legal technicality.

And that is when, according to another county judge—C. C. Cummings writing in The Bohemian magazine in 1899—Tucker got out of politics and into real estate. Tucker anticipated the eventual arrival of the railroads in Fort Worth and the ensuing economic boom. He bought 160 acres south of town below the Fifth Ward.

And that is when, according to another county judge—C. C. Cummings writing in The Bohemian magazine in 1899—Tucker got out of politics and into real estate. Tucker anticipated the eventual arrival of the railroads in Fort Worth and the ensuing economic boom. He bought 160 acres south of town below the Fifth Ward.

Tucker built a mill, grinding corn and wheat, on today’s Jennings Avenue near where Fort Worth High School would be built in 1891. Most of the area’s early mills were powered by water, but Tucker’s mill was powered by a treadwheel turned by oxen.

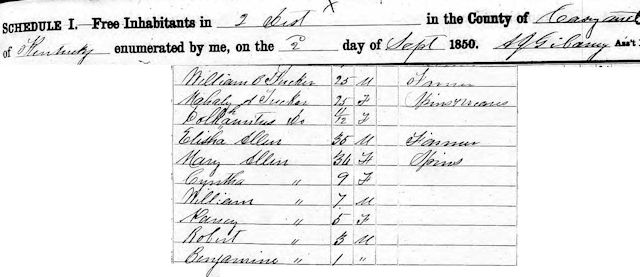

At the top of Tucker’s Hill a half-mile east of his mill in 1870 Tucker built the first house south of the Texas & Pacific tracks in what would become the near South Side. (Photo from The Bohemian, 1899.)

At the top of Tucker’s Hill a half-mile east of his mill in 1870 Tucker built the first house south of the Texas & Pacific tracks in what would become the near South Side. (Photo from The Bohemian, 1899.)

He cut oak, elm, and cottonwood trees along the river and hauled the timber to a sawmill. Then the milled lumber was hauled by “six-yoke ox teams” to Tucker’s Hill.

Lumber for weatherboarding was hauled by ox from Limestone County. The Telegram in 1907 wrote that the “bullwhacker” (driver of an ox wagon) on that trip was Tucker’s son Rowan. Rowan, like brother Bony Jr., would become a police officer.

The lumber for Tucker’s house was dressed by hand. The ornamental molding also was handmade.

The house was framed with mortise-and-tenon joints, not nails.

At a time when people were still building log cabins, Tucker built himself a showcase: two stories, ten rooms. “By long odds the finest dwelling in this part of the state,” the Telegram wrote.

The Telegram wrote that the house, with six Tucker children, became “the rendezvous for all of the young people in town.”

In 1870 the city of Fort Worth was largely confined to today’s downtown area, which is flat.

Even a decade later, because most buildings were less than three stories high, the Tuckers from the second floor of their house on top of Tucker Hill probably could see the observation tower of the 1877 courthouse more than a mile to the north.

Even in 1899, after almost thirty years of development, Judge Cummings wrote that the Tucker house “commands a superb view of the surrounding city and country.”

Having built the first house south of the railroad tracks, Tucker then became the first developer of what would become the South Side. He platted most of his 160 acres as “Tucker Addition.”

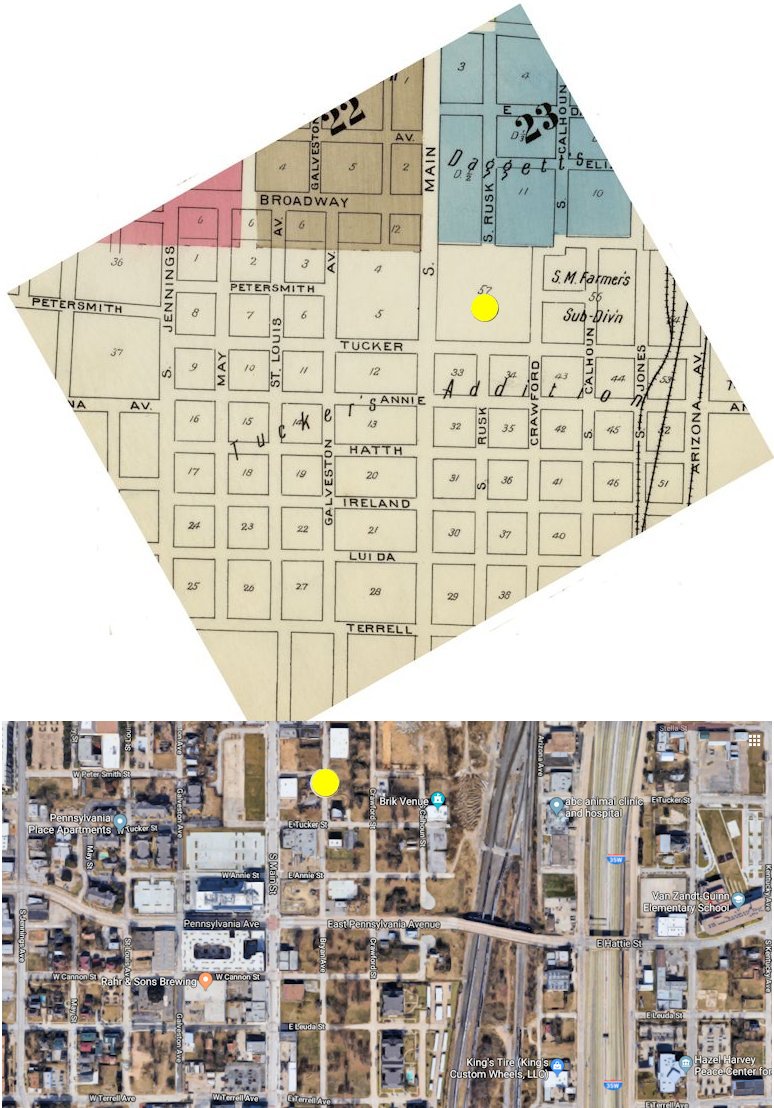

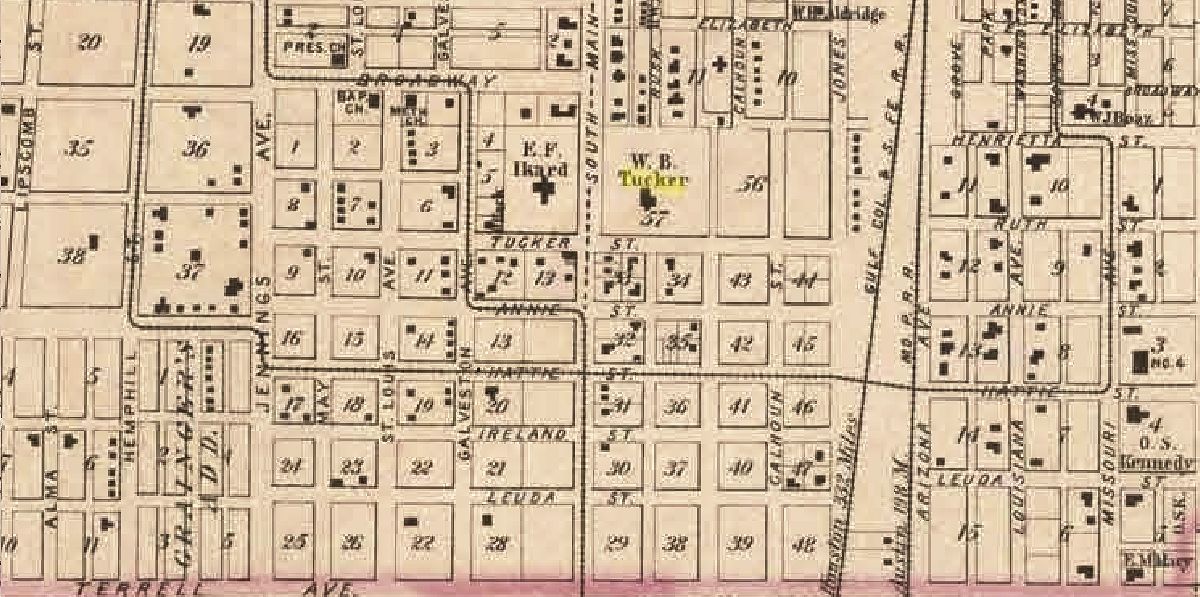

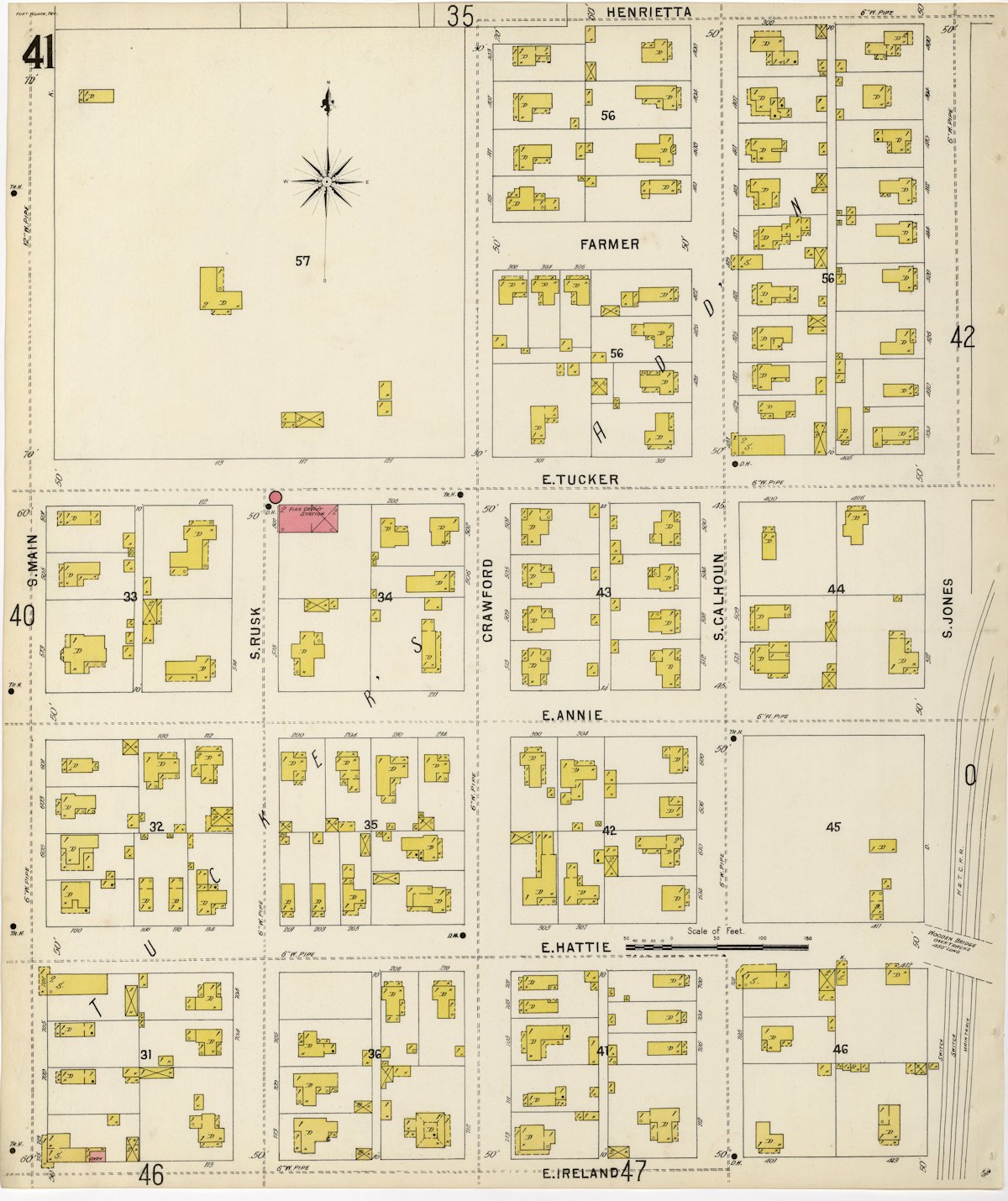

The 1898 map shows that Tucker retained a four-block area (block 57) as his residence.

The 1898 map shows that Tucker retained a four-block area (block 57) as his residence.

The Telegram wrote in 1907 that the Tucker Addition lies between Kentucky and Jennings streets (east to west). The north and south boundaries are Peter Smith and Terrell streets.

Today the addition is mostly commercial and multifamily (and several long-vacant lots), with the Burlington Northern Santa Fe tracks and Interstate 35W on the eastern edge.

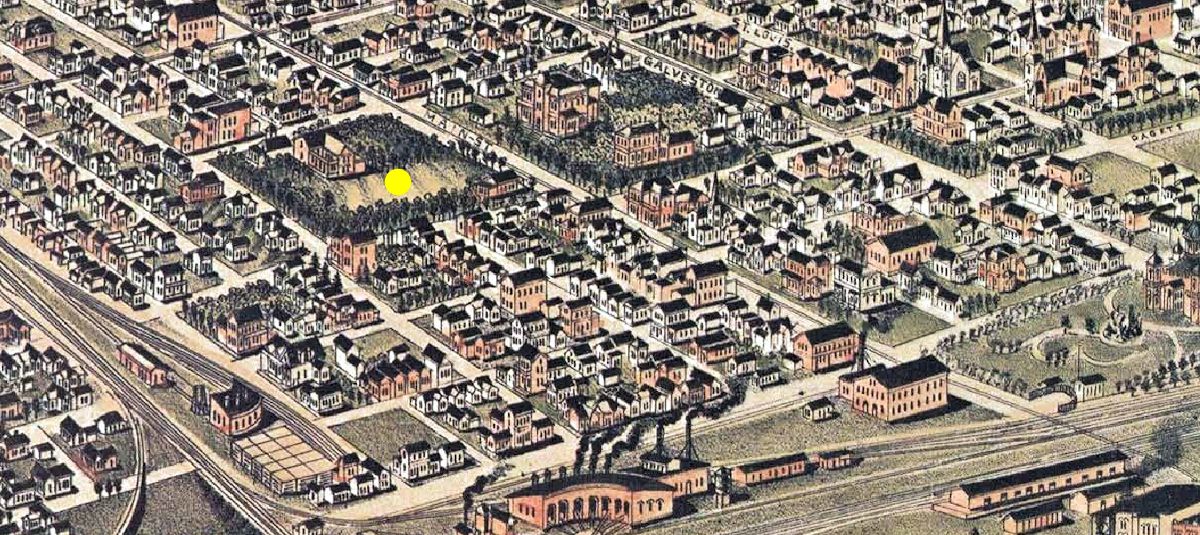

The yellow circles pinpoint the location of the Tucker house.

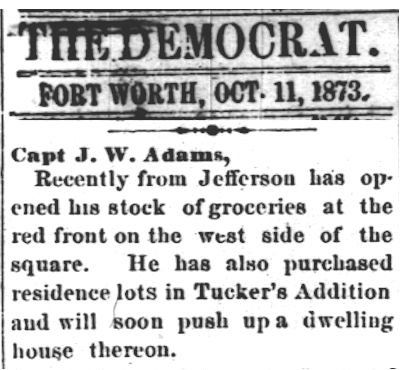

In 1873, even though his store was a mile away on the courthouse square, Captain J. W. Adams chose to build his home in the ’burbs: Tucker Addition.

In 1873, even though his store was a mile away on the courthouse square, Captain J. W. Adams chose to build his home in the ’burbs: Tucker Addition.

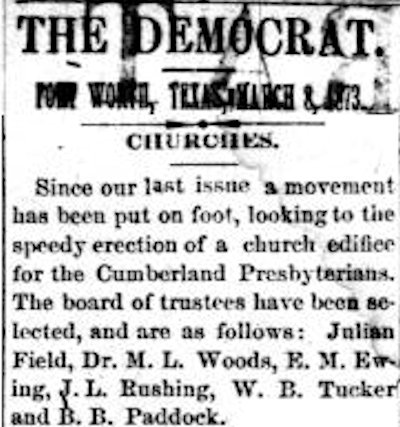

That same year Tucker, along with B. B. Paddock and Julian Feild, was a leader in an effort to build a Cumberland Presbyterian church.

That same year Tucker, along with B. B. Paddock and Julian Feild, was a leader in an effort to build a Cumberland Presbyterian church.

Not surprisingly, Tucker also was among the many civic leaders who helped bring the first railroad to town in 1876.

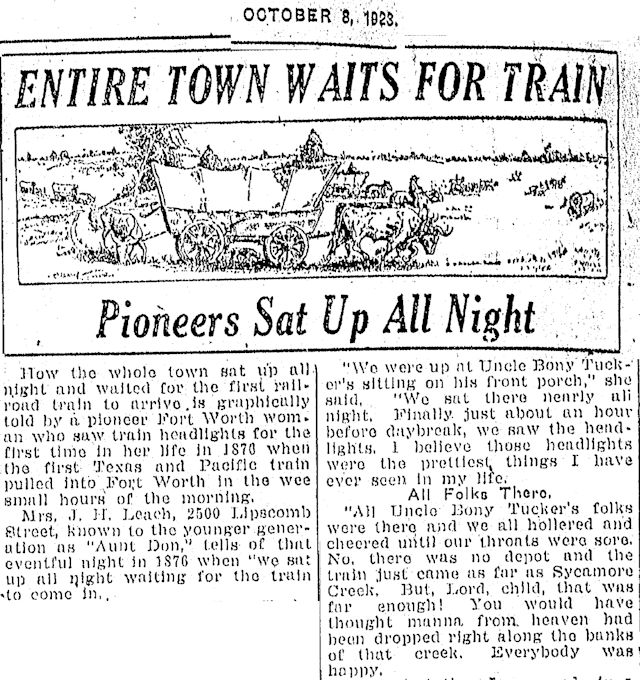

In 1923 Mrs. J. H. Leach recalled sitting on Bony Tucker’s porch and watching for “the first railroad train to arrive” “just about an hour before daybreak.” She recalled that the train approached only as far as Sycamore Creek. She may have been describing the construction train delivering men and materials to build the railroad bridge over the creek. According to the Democrat, the first train arrived on July 19 at 11:23 a.m.

In 1923 Mrs. J. H. Leach recalled sitting on Bony Tucker’s porch and watching for “the first railroad train to arrive” “just about an hour before daybreak.” She recalled that the train approached only as far as Sycamore Creek. She may have been describing the construction train delivering men and materials to build the railroad bridge over the creek. According to the Democrat, the first train arrived on July 19 at 11:23 a.m.

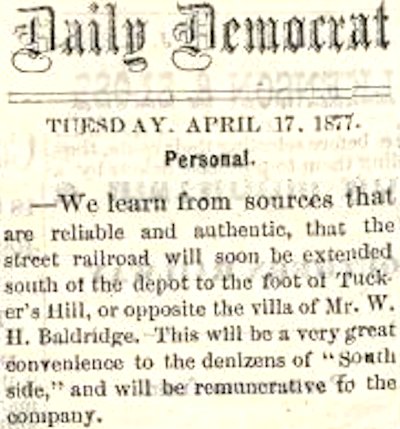

The year 1876 brought both the railroad and streetcar service to Fort Worth. By 1877 there was talk of extending the streetcar track south of the T&P depot across the railroad tracks to the foot of Tucker Hill. W. H. Baldridge lived on Main Street at the railroad tracks. He was a conductor on the T&P.

The year 1876 brought both the railroad and streetcar service to Fort Worth. By 1877 there was talk of extending the streetcar track south of the T&P depot across the railroad tracks to the foot of Tucker Hill. W. H. Baldridge lived on Main Street at the railroad tracks. He was a conductor on the T&P.

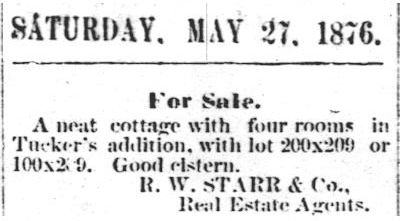

![]() In 1877 Tucker listed himself in the city directory as “capitalist.”

In 1877 Tucker listed himself in the city directory as “capitalist.”

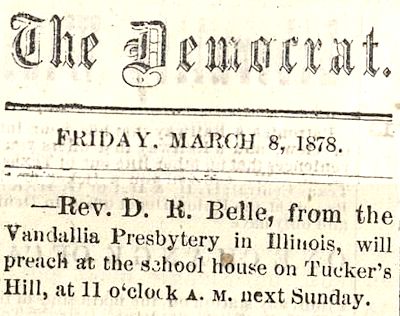

By 1878 Tucker Hill had a school. (Fort Worth would not have a public school system until 1882.)

By 1878 Tucker Hill had a school. (Fort Worth would not have a public school system until 1882.)

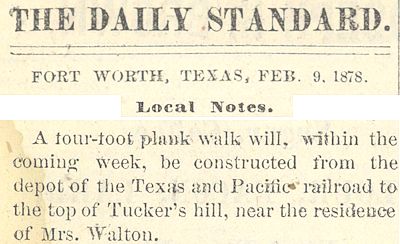

That same year a wooden sidewalk was planned from the depot to the top of Tucker Hill.

That same year a wooden sidewalk was planned from the depot to the top of Tucker Hill.

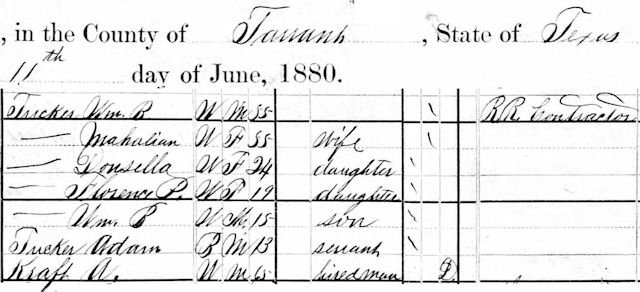

Tucker listed himself as a “railroad contractor” in 1880.

Tucker listed himself as a “railroad contractor” in 1880.

With the arrival of the railroad in 1876, Tucker’s gamble of 1867 began to pay off. Tucker Addition was only two thousand feet from the depot. Fort Worth began to grow. The population increased; land for housing was in demand. Tucker Addition, like the rest of Fort Worth, boomed.

With the arrival of the railroad in 1876, Tucker’s gamble of 1867 began to pay off. Tucker Addition was only two thousand feet from the depot. Fort Worth began to grow. The population increased; land for housing was in demand. Tucker Addition, like the rest of Fort Worth, boomed.

By 1885 Tucker Addition was in the city limits but still sparsely developed. Note that Tucker retained those four square blocks for his residence. The big cross-shaped house across Main Street from the Tucker homestead belonged to cattleman Elisha Floyd Ikard. Ikard, a Texas Ranger in the 1870s, controlled 150,000 acres of grazing land in the 1880s.

By 1885 Tucker Addition was in the city limits but still sparsely developed. Note that Tucker retained those four square blocks for his residence. The big cross-shaped house across Main Street from the Tucker homestead belonged to cattleman Elisha Floyd Ikard. Ikard, a Texas Ranger in the 1870s, controlled 150,000 acres of grazing land in the 1880s.

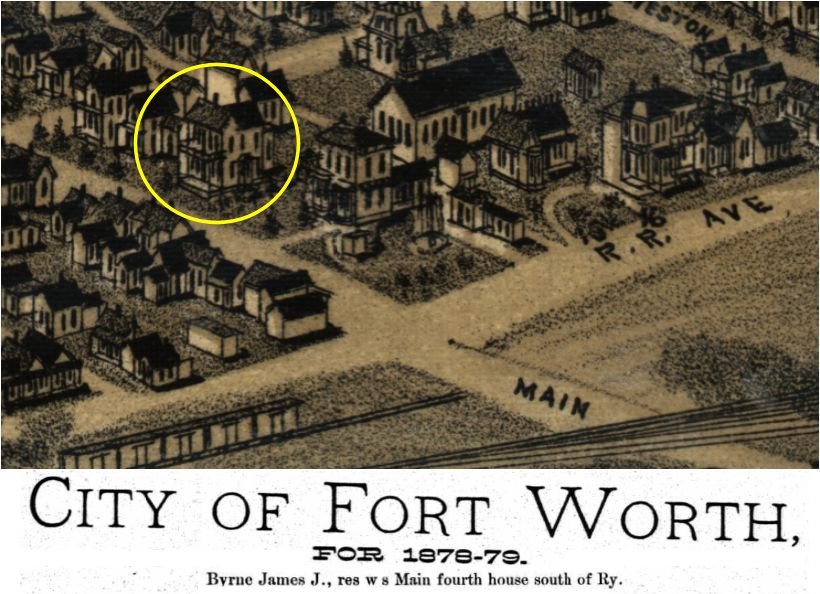

At the foot of Tucker Hill was the home of General J. J. Byrne, who lived on the west side of Main Street south of the railroad tracks, possibly in the circled house. Byrne’s house later became the Protestant Sanitarium. General Byrne in 1880 foresaw his own death.

At the foot of Tucker Hill was the home of General J. J. Byrne, who lived on the west side of Main Street south of the railroad tracks, possibly in the circled house. Byrne’s house later became the Protestant Sanitarium. General Byrne in 1880 foresaw his own death.

By 1891, this bird’s-eye-view map shows, Tucker Addition was much more developed. Tucker held on to his four blocks at East Tucker and Main streets. The T&P roundhouse is at the bottom of the map. The big Ikard house is visible across Main Street.

By 1891, this bird’s-eye-view map shows, Tucker Addition was much more developed. Tucker held on to his four blocks at East Tucker and Main streets. The T&P roundhouse is at the bottom of the map. The big Ikard house is visible across Main Street.

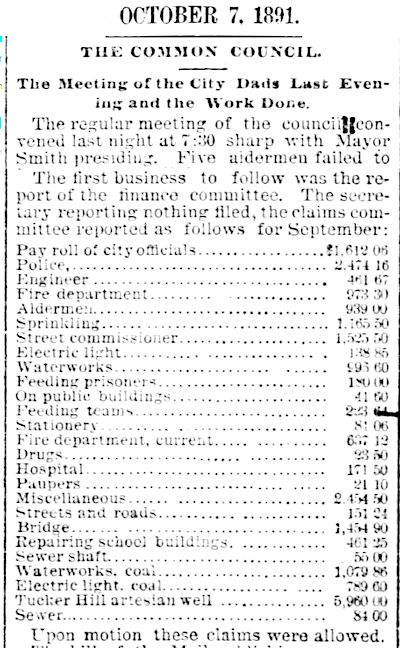

In 1891 the city drilled an artesian well on Tucker’s Hill. The waterworks drew water from the river and artesian wells.

In 1891 the city drilled an artesian well on Tucker’s Hill. The waterworks drew water from the river and artesian wells.

The Tucker house was located at 115 East Tucker Street just north of where the Tucker Hill fire station (no. 5) would be built on Bryan Avenue after the South Side fire of 1909. This 1898 map shows in the upper left corner the four blocks that Tucker retained as his residence.

The Tucker house was located at 115 East Tucker Street just north of where the Tucker Hill fire station (no. 5) would be built on Bryan Avenue after the South Side fire of 1909. This 1898 map shows in the upper left corner the four blocks that Tucker retained as his residence.

In 1899 Judge Cummings wrote, “Mr. Tucker and his [second] wife are . . . passing their old age in leisure and comfort.”

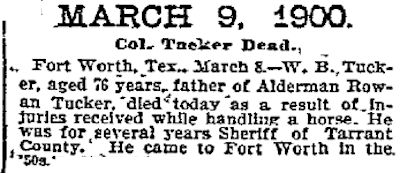

But not for long. The man known as “father of the South Side” died in 1900.

But not for long. The man known as “father of the South Side” died in 1900.

William Bonaparte Tucker, farmer-turned-county judge-turned-developer, is buried in Pioneers Rest Cemetery.

William Bonaparte Tucker, farmer-turned-county judge-turned-developer, is buried in Pioneers Rest Cemetery.

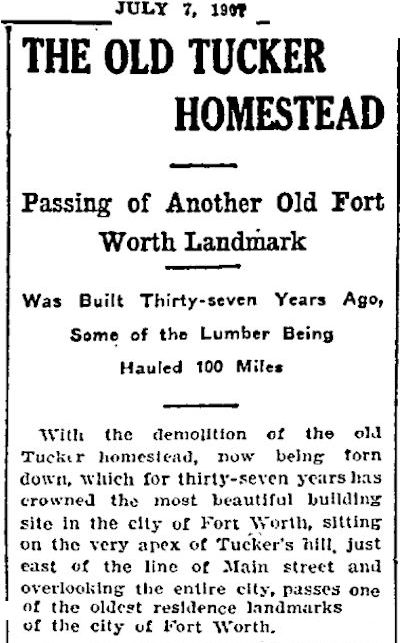

The house that he built at the top of Tucker’s Hill in 1870 was torn down in 1907.

The house that he built at the top of Tucker’s Hill in 1870 was torn down in 1907.

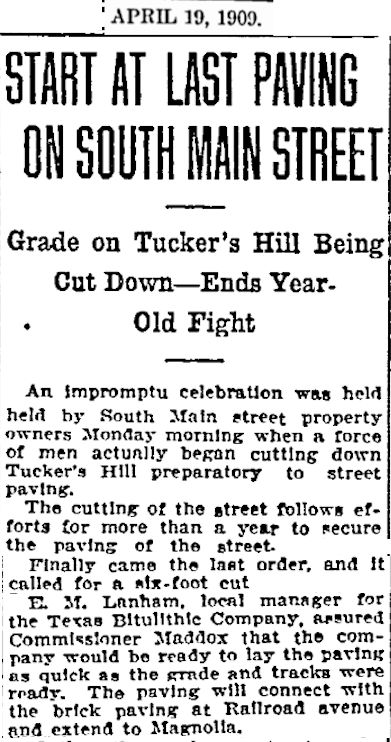

Change was not done with Tucker Hill. As steep as that hill seems to bicyclists today, it once was even steeper. In 1909, at the request of business owners along South Main Street, the grade of Main Street up Tucker Hill was cut down by six feet, and Main was paved from Railroad Avenue (Vickery Boulevard today) south to Magnolia Street.

Change was not done with Tucker Hill. As steep as that hill seems to bicyclists today, it once was even steeper. In 1909, at the request of business owners along South Main Street, the grade of Main Street up Tucker Hill was cut down by six feet, and Main was paved from Railroad Avenue (Vickery Boulevard today) south to Magnolia Street.

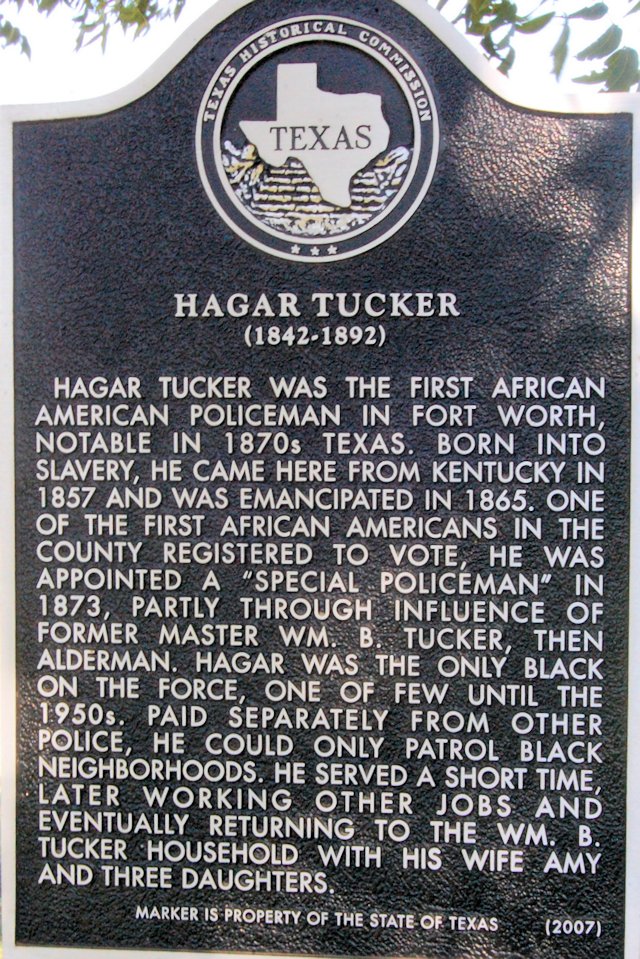

Footnote: There’s another Tucker of historical significance: Hagar Tucker, a former slave of W. B. Tucker, became Fort Worth’s first African-American police officer in 1873 through the influence of W. B. Tucker.

Footnote: There’s another Tucker of historical significance: Hagar Tucker, a former slave of W. B. Tucker, became Fort Worth’s first African-American police officer in 1873 through the influence of W. B. Tucker.