During the days of the wild West, just as today, the legal wheels of justice (the court system) turned slowly (motions to delay, mistrials, retrials, appeals, stays, continuances, etc.). On the other hand, the illegal wheels of justice (vigilantism) during the days of the wild West virtually burned rubber (lynching).

And those illegal wheels still turned now and then in the twentieth century. In fact, in 1920 they rolled Tom Vickery to his grave.

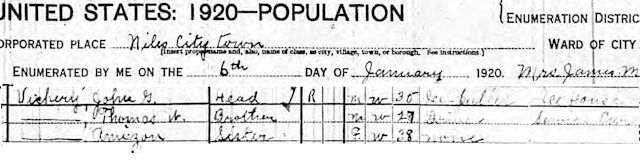

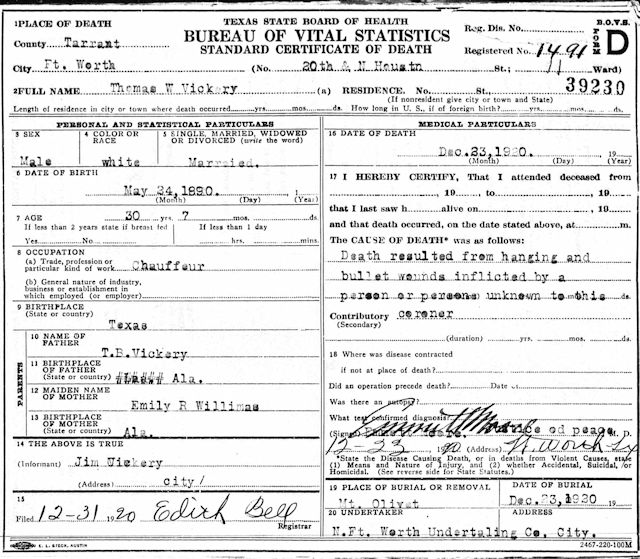

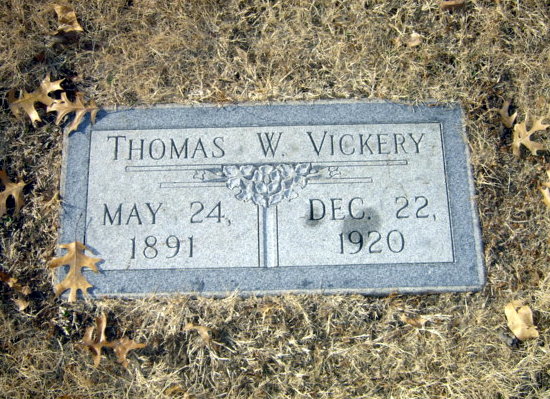

Vickery, born in 1891, worked as a mechanic and a service car driver (chauffeur) when not engaged in less legitimate pursuits.

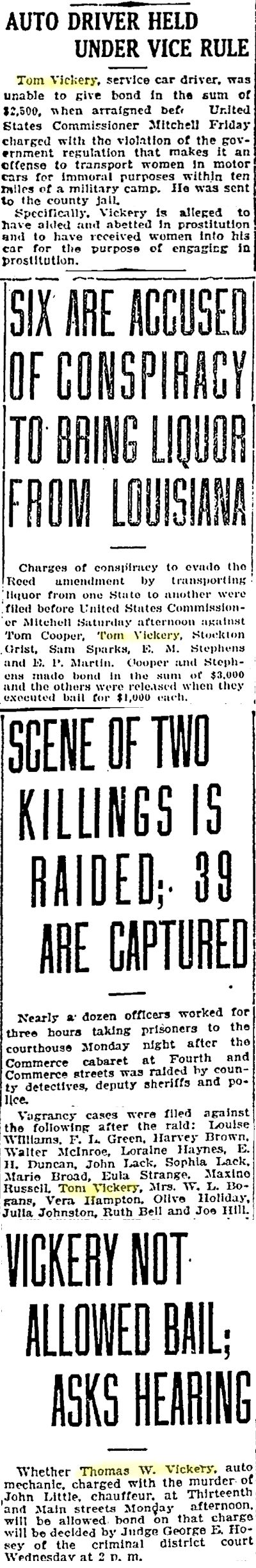

For example, in 1917-1918, as the city clamped down on vice to protect the Sammies at Camp Bowie, Vickery was accused of using his car to engage in prostitution and to bring liquor across state lines. He was charged with vagrancy after a raid on a downtown “cabaret.” Most seriously, he was charged with murdering fellow chauffeur John Little. Vickery claimed self-defense, said he shot Little after Little threatened him with a knife and vowed “to kill him within six months if he stays in Fort Worth.”

For example, in 1917-1918, as the city clamped down on vice to protect the Sammies at Camp Bowie, Vickery was accused of using his car to engage in prostitution and to bring liquor across state lines. He was charged with vagrancy after a raid on a downtown “cabaret.” Most seriously, he was charged with murdering fellow chauffeur John Little. Vickery claimed self-defense, said he shot Little after Little threatened him with a knife and vowed “to kill him within six months if he stays in Fort Worth.”

Meanwhile, Mrs. Little—who admitted to having “improper relations” with Vickery—was under indictment for assault to murder her husband when Tom Vickery finished what she had started.

Vickery was never tried for killing Little because of lack of evidence: No one was brave enough to testify against a killer. Charges also were dropped against Mrs. Little.

Soon after, the widow swapped her mourning veil for a bridal veil: She and Tom Vickery were wed.

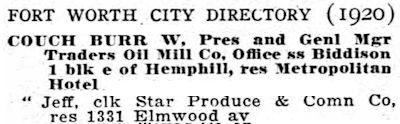

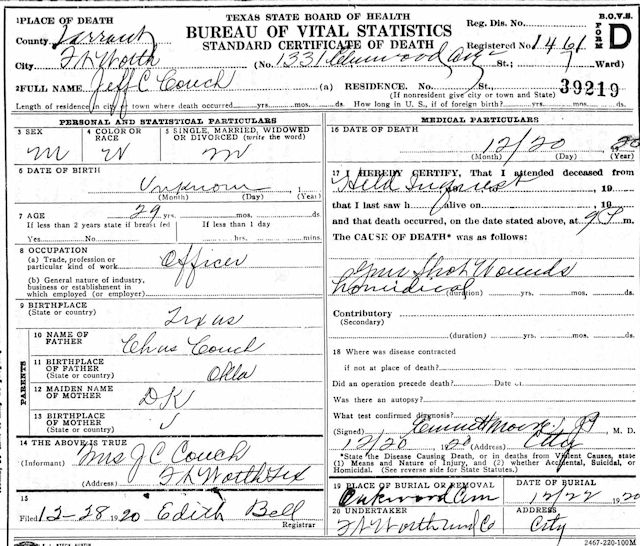

Fast-forward to 1920. Jeff Couch, twenty-six, began the year as a clerk in a wholesale produce company. But in October, the Star-Telegram reported, he joined the police force. Not surprising: Couch’s father and stepfather had been Fort Worth police officers.

Fast-forward to 1920. Jeff Couch, twenty-six, began the year as a clerk in a wholesale produce company. But in October, the Star-Telegram reported, he joined the police force. Not surprising: Couch’s father and stepfather had been Fort Worth police officers.

In November Couch was assigned to Hell’s Half Acre—and the night beat at that. Even in 1920, after the cleanup triggered by the installation of Camp Bowie, the Acre was still a dangerous place.

Couch took on the Acre after only one month on the job, with no formal police training (police academies were still decades away), and with nothing to recommend him for police work except that his father and stepfather had been policemen, and thus Couch had more knowledge of policing than did the average twenty-six-year-old wholesale produce clerk.

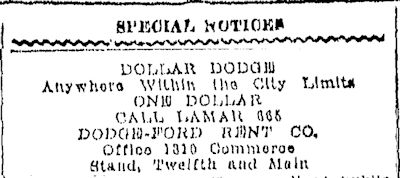

Fast-forward to December 20. Tom Vickery was working as a service car driver at Dollar Dodge, a limousine company on Commerce at East 12th Street. ($1 would be $12 today.)

Fast-forward to December 20. Tom Vickery was working as a service car driver at Dollar Dodge, a limousine company on Commerce at East 12th Street. ($1 would be $12 today.)

That night officer Jeff Couch went to Dollar Dodge to investigate a report that gunshots had been fired. Couch found Tom Vickery drunk and waving a pistol. Equally drunk but unarmed was Niles City alderman Robert W. Dawson. Vickery had chauffeured Dawson earlier in the day, and now Dawson was accusing Vickery of stealing $95 from him. The two men had argued, leading Vickery to begin firing his pistol to make his points.

In the Dollar Dodge office were the company manager, a Mr. Ford, and the wife of H. F. Neal, owner of the company. Ford and Mrs. Neal were afraid of Vickery when he was drunk and armed.

Officer Couch’s inexperience quickly began to show. Rather than confront Vickery, Couch went into the office to talk to Ford and Mrs. Neal.

Seeing his chance, Vickery left the premises.

Witnesses said Jeff Couch had not drawn his gun, had made no attempt to arrest Vickery.

He would get another chance.

Dollar Dodge owner H. F. Neal arrived and asked Couch to stay in case Vickery returned. Neal, too, feared Vickery when the latter had been drinking.

Couch agreed to stay.

Then Ford asked Couch to accompany him as he drove alderman Dawson somewhere to sleep it off.

Neal later told the Star-Telegram that Ford and officer Couch “drove out of the garage and had gone about fifty yards south on Commerce Street when Vickery came up and called to them, commanding them to stop. They stopped and drove back to the garage. Vickery had a gun in each hand. Ford and Couch got out of the car. Vickery was abusing all of us, waving and threatening with his guns. “Policeman Couch seemed scared,” Neal said. “I was still trying to coax Vickery to stop when he turned on me, cursed and shot at me. I ran into the office and he followed. While he and I were in my office he telephoned for a [taxi] at once. Policeman Couch remained out in front all during that time.

“Vickery went back to the sedan and tried to awaken [Dawson] in the rear seat. About that time the [taxi] which Vickery had phoned for drove up. Vickery and [Dawson] left. I asked Couch why he did not arrest Vickery. He didn’t answer. Vickery then drove back to my office, got out of his car with a gun in each hand.”

Still officer Couch did nothing.

He was running out of chances.

Vickery, holding two guns on Neal and officer Couch, marched them into the Dollar Dodge garage.

Then he began shooting.

Vickery shot Jeff Couch seven times in the back—just two blocks from where Vickery had shot John Little three years earlier. Couch fell to the floor, his pistol still in its holster.

Vickery fled in a car.

Forty minutes later he surrendered at the sheriff’s office and was jailed.

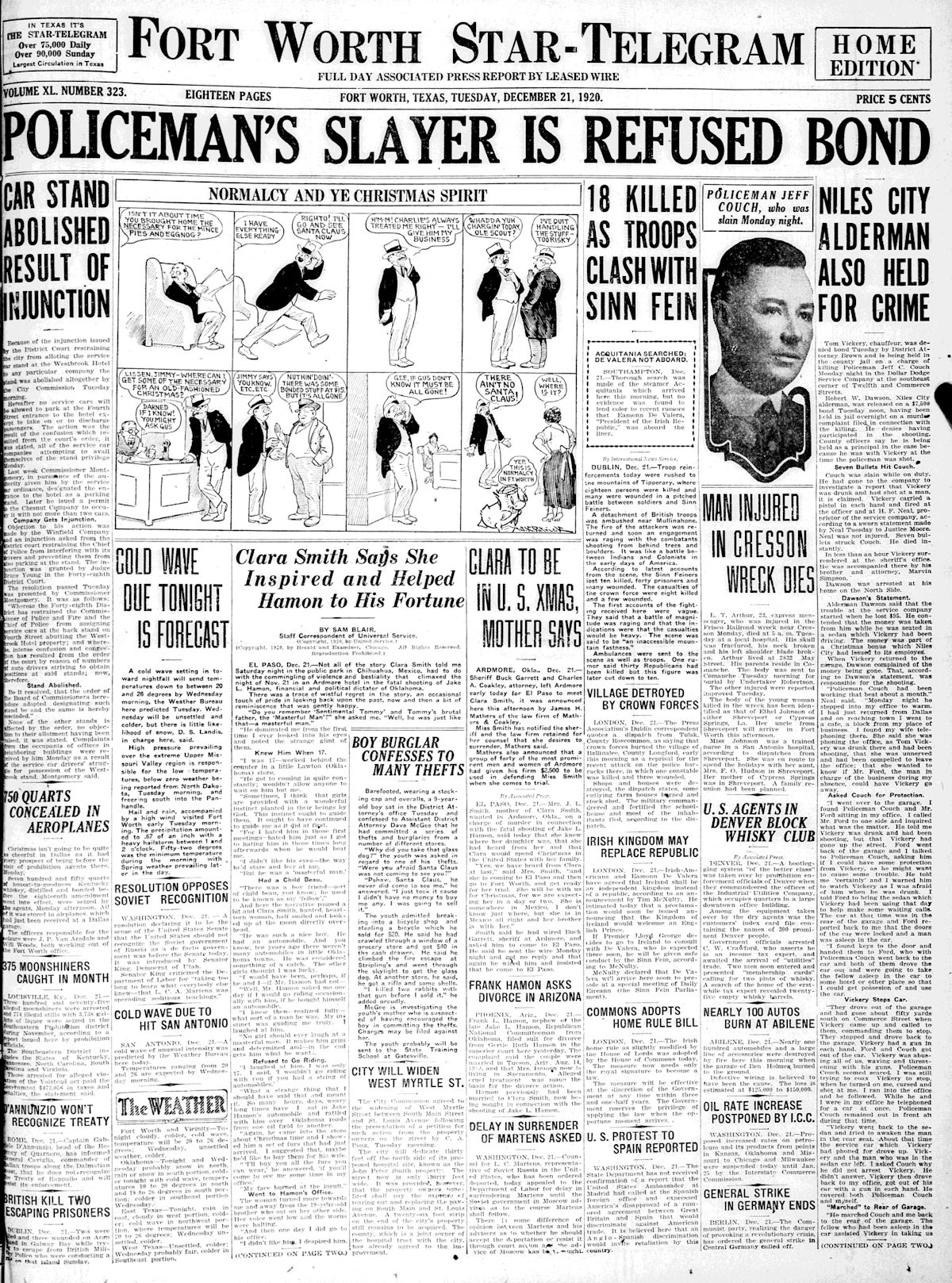

Because the Star-Telegram was an evening newspaper at the time, its first edition after the nighttime murder had to report both that officer Couch had been killed and that Tom Vickery had been arrested and denied bond.

Because the Star-Telegram was an evening newspaper at the time, its first edition after the nighttime murder had to report both that officer Couch had been killed and that Tom Vickery had been arrested and denied bond.

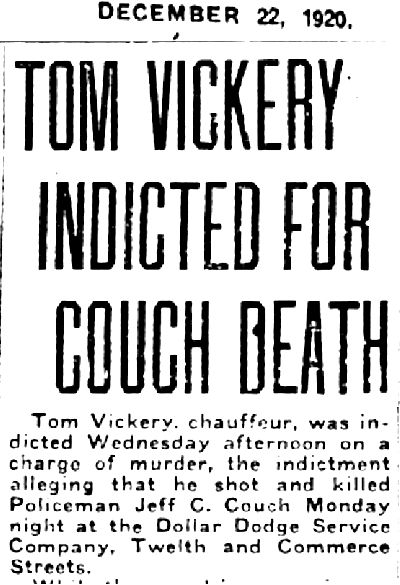

On December 22 Tom Vickery was indicted for first-degree murder.

On December 22 Tom Vickery was indicted for first-degree murder.

That same day officer Jeff Couch, a produce clerk with a badge, was buried in Oakwood Cemetery. Six police officers served as pallbearers. He was buried near his father and stepfather—three police officers in a family plot.

That same day officer Jeff Couch, a produce clerk with a badge, was buried in Oakwood Cemetery. Six police officers served as pallbearers. He was buried near his father and stepfather—three police officers in a family plot.

The inscription from Couch’s widow at the bottom on the tombstone reads: “You who are far yet evermore nearest. Since we together solved love’s golden clue. Across the leagues that sunder us, my dearest my thoughts forever will fare back to you.”

![]() His name is engraved on the wall of the Fort Worth Police and Firefighters Memorial in Trinity Park.

His name is engraved on the wall of the Fort Worth Police and Firefighters Memorial in Trinity Park.

Meanwhile Tom Vickery’s lawyer, Marvin Simpson, said two city policemen told him that Vickery would be killed if he was released on bond.

Despite that threat and the initial denial of bond, Simpson tried to arrange a bond hearing to free his client. But Simpson was having difficulty. Part of the difficulty lay in the relaxed work schedule just three days before Christmas. And part of the difficulty, historians Dr. Richard Selcer and Kevin Foster write in Written in Blood: The History of Fort Worth’s Fallen Lawmen, lay in the fact that no one in the legal system was overly eager to set free a cop killer.

So, Vickery remained in jail in an isolated cell.

Which should have been the safest place for him.

It wasn’t.

After 11 p.m. on December 22 twenty-five to thirty men arrived at the jail in four cars. The men were armed with pistols. They wore black masks and “uniforms,” although witnesses later were vague about what kind of uniforms.

The mob divided into two submobs. One submob remained outside the jail building at a basement window of the office of Deputy Sheriff Barney Fitch.

The other submob entered the jail and went to the jailer’s office, where R. A. Cox was on duty alone.

The mob knew its way around the jail.

Cox heard a knock at his door.

The Star-Telegram wrote: “When he opened the door several pistols were flashed in his face. About twenty men were in the corridor, every one of whom wore a mask and carried a pistol. Cox was ordered to take the mob to Vickery’s cell and to open the cell. He told the mob that he had been on the job only a short time and that he did not know the combination to the locks. However, he was forced to take the men to the fifth floor of the jail where Vickery’s cell was located. When he could not open the combination the masked men threatened to take his life.”

Cox told the mob: “I don’t know the combination—I can’t open the cell—if you want to kill me for that, go ahead.”

“We will get someone who knows the combination,” one of the mob said.

While a few men guarded Cox, the majority went to the hall that adjoins the office of Deputy Sheriff Fitch. Fitch was awakened by noises in the hall. He could see men walking past his office. Ile picked up his telephone and called the police station, asking for reinforcements.

“I then started to my trunk to get my pistol,” Fitch recalled. “The trunk is in the corner of the room, almost under a window which was raised. As I started to raise the trunk lid, three pistols were poked through the window at me. I jumped back into the corner of the room.

“‘Don’t you move in there or we will get you,’ the men told me. I told them not to move out there or I would ‘get them.’ However, I had not succeeded in getting my pistol from my trunk and I was unarmed. I was stalling for time, waiting for aid from the police station. The men opened my door and came in. Every man had a pistol on me.”

The mob escorted Fitch at gunpoint to the cellblock on the fifth floor. They ordered him to open the cellblock door. Again stalling for time, Fitch later said, he misdialed the combination twice, telling the mob that he had forgotten the combination.

“If you think more of Vickery’s life than you do of your own, all right,” one of the vigilantes said.

Fitch got the combination right on the third try, and the mob headed down the row of cells.

The Star-Telegram wrote: “The men went directly to Vickery’s cell. Vickery had been aroused, probably by the walking of the men outside. Several pistols were pointed at him through the bars.

“‘We want you,’ said one of the masked men, ‘get up from there!’

“Vickery said, ‘What do you want me for?’ One of the men answered, ‘It doesn’t make a damn bit of difference what for. Get up!’

“‘Well, you are getting an innocent man,’ was Vickery’s only remark as he obeyed the commands to leave his cell.”

Now one submob marched Vickery to the elevator and took him down and out to the automobiles waiting at the curb. As he left the jail Vickery was wearing only trousers, undershirt, and socks. He wore no shoes. Vickery made no resistance, didn’t utter a word from the time he was taken from his cell until he was out of the building. Another submob marched Cox and Fitch downstairs and warned them to remain quiet. Then all of the submobs assembled at the waiting automobiles.

Police Chief R. R. Porter later said that he was at home about 11:40 p.m. when he received an anonymous phone call telling him where the body of Tom Vickery could be found. Porter and Justice of the Peace Emmett Moore drove to that location.

The Star-Telegram wrote: “Vickery’s bullet-riddled body was found under a hackberry tree early Thursday morning on the road that leads from Samuels Avenue to the packing houses. . . . Directly over the body was a rope suspended from a limb of the tree. After Vickery was hanged, the loop around his neck was cut by bullets from pistols and the body had fallen to the ground. Examination of the body proved that the neck had not been broken by hanging, but by bullets instead. Besides the bullet wounds to Vickery’s neck, there were four bullet holes in his chest.

“That the mob worked quietly is evidenced by the fact that no sound of the trouble was heard by residents in the home of A. S. Dingee, 106 Prosser Street, less than 300 yards from the scene of the lynching, until the firing of the shots was started. According to Mrs. Dingee, she was awakened by two shots in rapid succession between 11:30 and 12 o’clock and followed just a minute later by ten or twelve more in quick succession.”

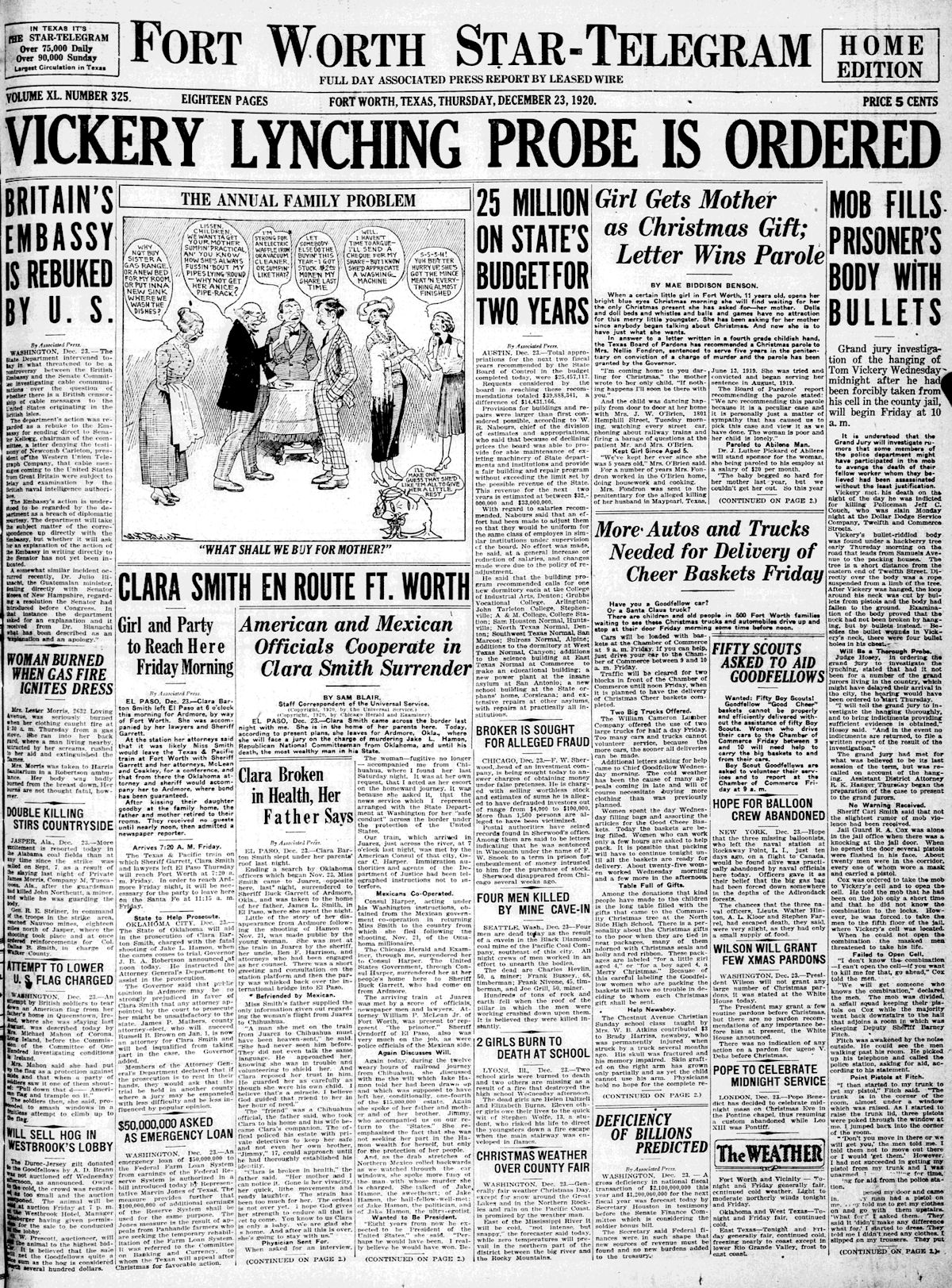

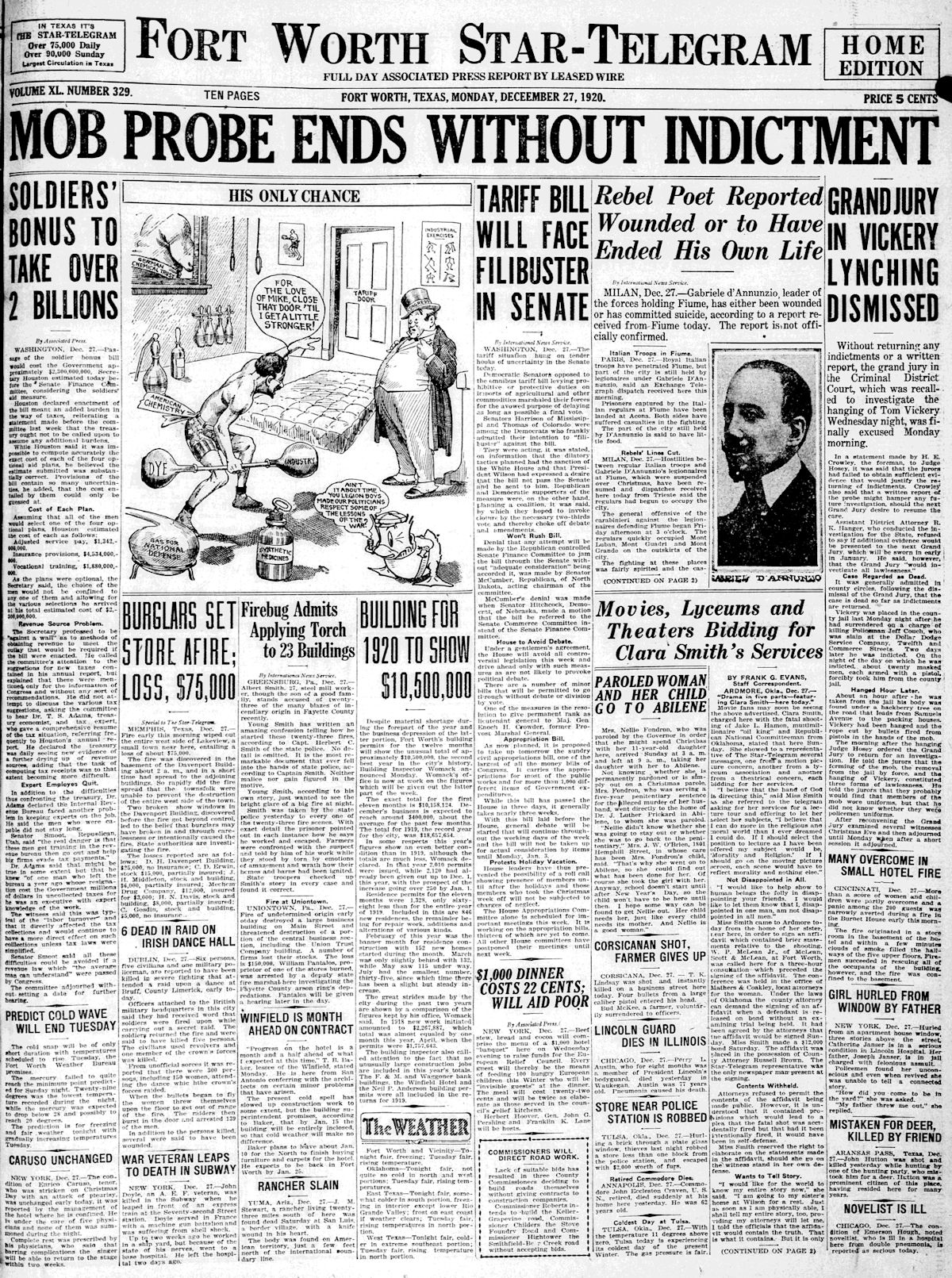

Again, the first edition of the Star-Telegram after the lynching had to report both that Tom Vickery had been lynched and that a grand jury would begin investigating the lynching on December 24.

Again, the first edition of the Star-Telegram after the lynching had to report both that Tom Vickery had been lynched and that a grand jury would begin investigating the lynching on December 24.

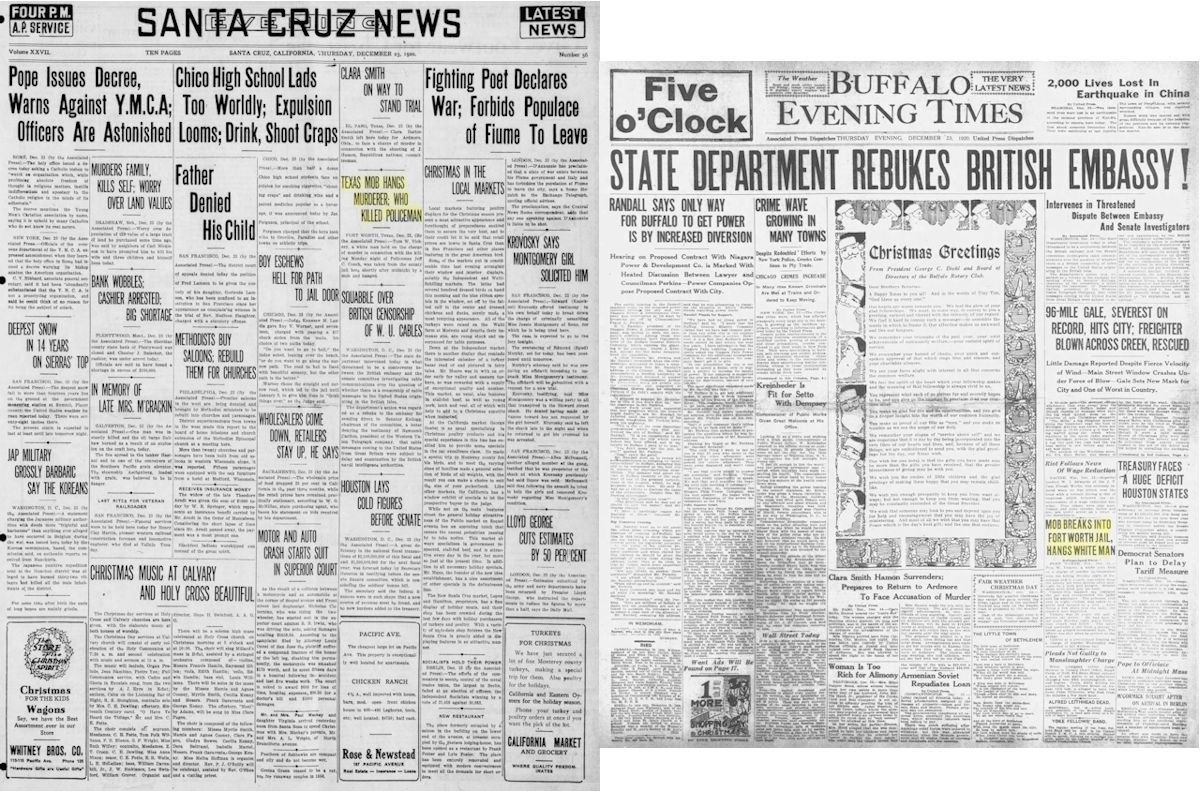

The lynching was on front pages from coast to coast.

The lynching was on front pages from coast to coast.

Tom Vickery was buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery.

Tom Vickery was buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery.

Deputy Sheriff William M. Rea, a veteran lawman, said the lynching was the first illegal hanging in the county. But, for example, two abolitionists were hanged here in 1860.

As the grand jury began to call witnesses, the Star-Telegram wrote: “It is understood that the Grand Jury will investigate rumors that some members of the police department might have participated in the mob to avenge the death of their fellow worker whom they believed had been assassinated without the least justification.”

So, avenging police officers may have been members of the mob. Another rumor implicated the Ku Klux Klan, which was becoming prominent in Fort Worth. In fact, in Fort Worth in 1920 the Klan and the police were not mutually exclusive: Some police officers were members of the Klan.

As often happened after crimes by anonymous vigilantes, no one was indicted for the lynching.

As often happened after crimes by anonymous vigilantes, no one was indicted for the lynching.

Indeed, the illegal wheels of justice would turn again. Fast-forward to 1921. Another year, another Christmas, another lynching: On December 11, 1921 packing plant strike breaker Fred D. Rouse would be taken from his hospital bed and shot and lynched by a mob at the same tree where Tom Vickery was shot and lynched.