He is not as well remembered as other Cowtown cattleman-capitalists (W. T. Waggoner, Samuel Burk Burnett, Winfield Scott, M. B. Loyd, E. B. Harrold, Marion Sansom, George T. and William D. Reynolds, C. A. O’Keefe, or even Fountain Goodlet Oxsheer).

But Elisha Floyd Ikard, like those other men, lived in an era of remarkable cultural and technological change, an era when a rancher could start out fighting Native Americans on the frontier and making cattle drives on the Chisholm Trail and end up living in a mansion in the city and being driven to bank director meetings in a chauffeured automobile.

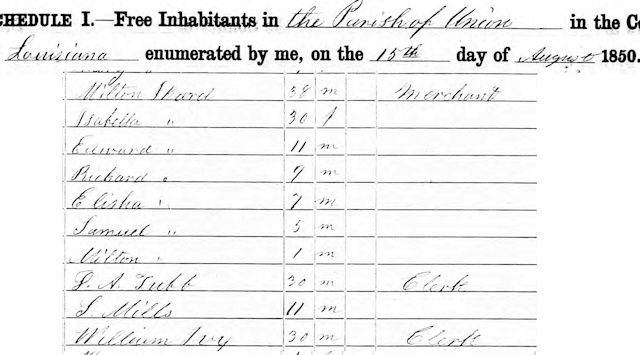

E. F. Ikard was born in 1844 in Mississippi to Dr. Milton and Isabella Ikard. By 1850 Dr. and Mrs. Ikard, with children and slaves, were in Louisiana.

E. F. Ikard was born in 1844 in Mississippi to Dr. Milton and Isabella Ikard. By 1850 Dr. and Mrs. Ikard, with children and slaves, were in Louisiana.

In 1855 the family and slaves moved to Parker County, Texas.

Cattle in Texas in the 1860s grazed on mostly open range—few fences. They tended to stray, especially southward in winter to avoid the cold. In 1865 E. F. and his brother William S. came up with a money-raising scheme: They rounded up stray cattle in Parker County. Then, carrying with them the brands of the stray cattle, they attended a meeting of ranchers. The brothers offered to sell the recovered cattle back to the ranchers, taking their payment in cash ($1 a head) or cattle. By that exchange the brothers got enough cash and cattle to start their own cattle business.

In 1867 the brothers drove their first herd to Kansas on the Chisholm Trail, made a profit, and were able to buy all the cattle they wanted on credit after that.

They made from one to four cattle drives to Kansas each year until the Missouri-Kansas-Texas railroad reached Denison in 1874, making shipping cattle to market by rail possible.

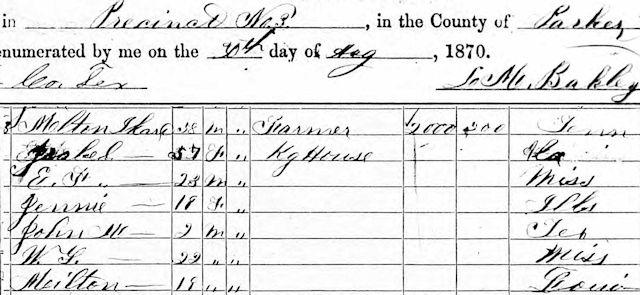

E. F. Ikard had three brothers in 1870. A fourth had been killed in the war.

E. F. Ikard had three brothers in 1870. A fourth had been killed in the war.

In 1871 brothers E. F. and William S. moved to Clay County, where they built a log cabin with a buffalo-hide roof. The brothers helped to organize the county and to lay out the town of Henrietta. E. F. built the county jail. There is an Ikard Street in downtown Henrietta.

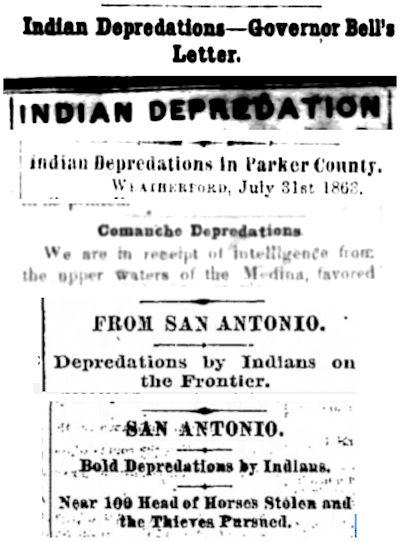

But north Texas in the mid-1870s was fraught with violence: Fifty years after Austin’s colony, white settlers and Native Americans were still at odds.

“Depredations” was newspapers’ favorite noun for offenses by Native Americans. No doubt if the Native Americans had published newspapers, they, too, might have used the same noun for offenses by white settlers.

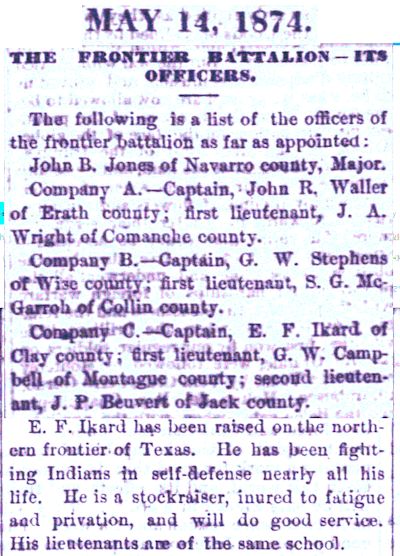

In 1874 Governor Richard Coke authorized formation of the Texas Rangers Frontier Battalion to protect white settlers against Native Americans but also to police white lawbreakers. The battalion during its first seventeen months engaged in twenty-one fights with Native Americans.

In 1874 Governor Richard Coke authorized formation of the Texas Rangers Frontier Battalion to protect white settlers against Native Americans but also to police white lawbreakers. The battalion during its first seventeen months engaged in twenty-one fights with Native Americans.

The battalion consisted of six companies. At age twenty-eight E. F. Ikard of Company C was the youngest of the six captains, according to Texas Rangers: Lives, Legend, and Legacy by Bob Alexander and Donaly E. Brice.

The Texas Rangers were often outnumbered.

The Texas Rangers were often outnumbered.

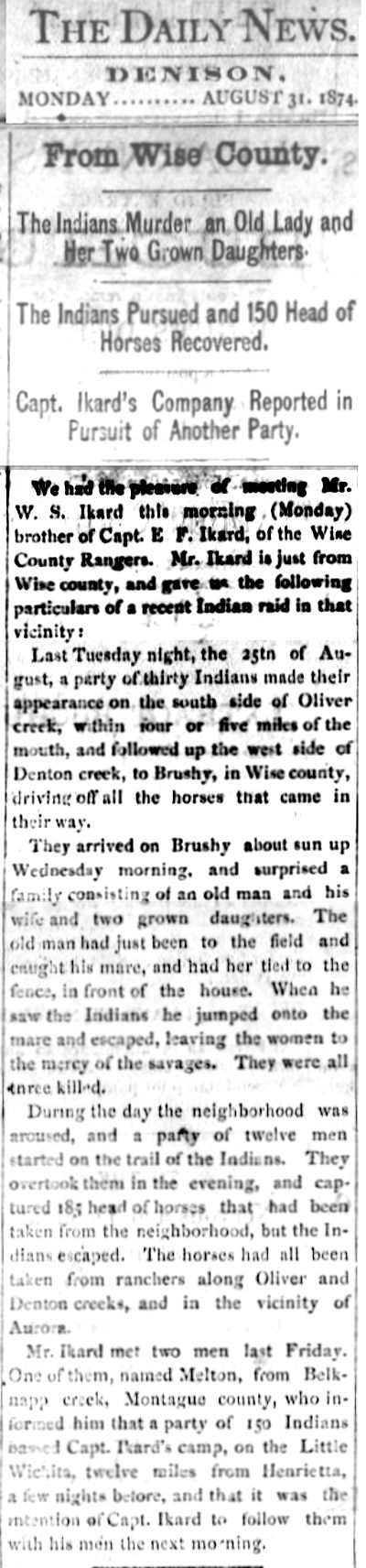

Brother William recounted an attack in Wise County to the Denison newspaper.

Brother William recounted an attack in Wise County to the Denison newspaper.

E. F. Ikard served as a Texas Ranger about one year and returned to ranching with his brother William.

E. F. Ikard served as a Texas Ranger about one year and returned to ranching with his brother William.

In 1876 William was credited with introducing Hereford cattle to Texas.

In the 1880s the brothers began expanding their cattle operation, buying grazing rights in north Texas and Oklahoma and buying ranchland (paying as little as fifty cents an acre) in and around Clay County until their 100,000-acre V-Bar Ranch made them among the most prominent cattlemen in the area. The brothers sold herds for sums as great as $350,000.

The Ikard brothers were among the first ranchers in north Texas to fence their ranges, but because they left gaps and gates in fences, they were not troubled by fence-cutting. Native Americans also did not harass the Ikards because the brothers hired Native American cowboys and paid Comanche Chief Quanah Parker for protection from raids.

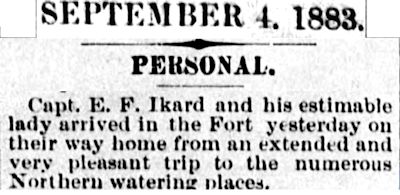

How life had changed for Ikard by 1883. No longer did he chase Native Americans on horseback or drive cattle up dusty trails. Now he traveled by train: Chicago, St. Louis, Denver. And the “watering places” he stopped at weren’t stock tanks.

How life had changed for Ikard by 1883. No longer did he chase Native Americans on horseback or drive cattle up dusty trails. Now he traveled by train: Chicago, St. Louis, Denver. And the “watering places” he stopped at weren’t stock tanks.

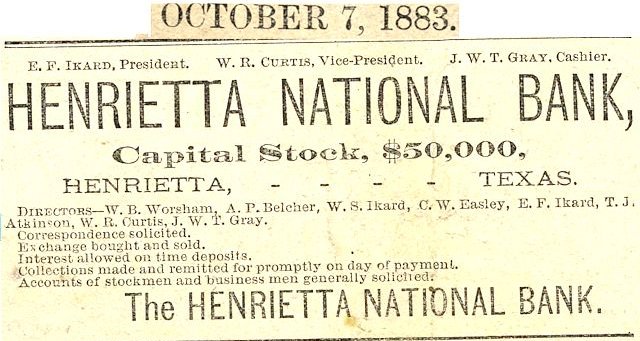

Like so many successful cattlemen, the Ikard brothers diversified into banking.

Like so many successful cattlemen, the Ikard brothers diversified into banking.

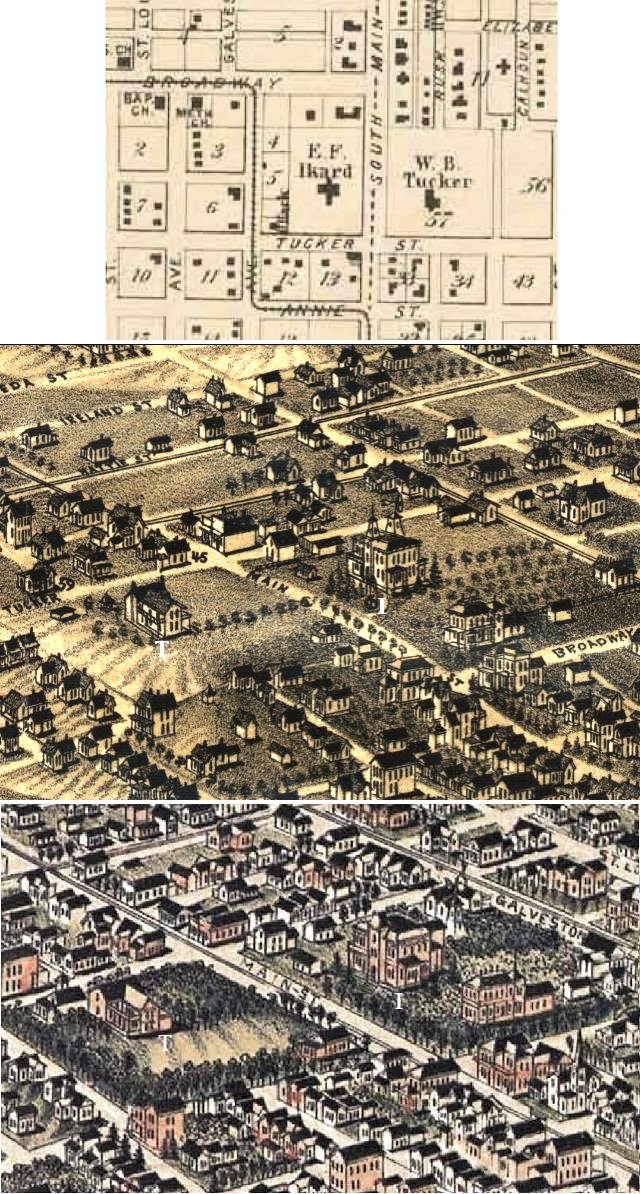

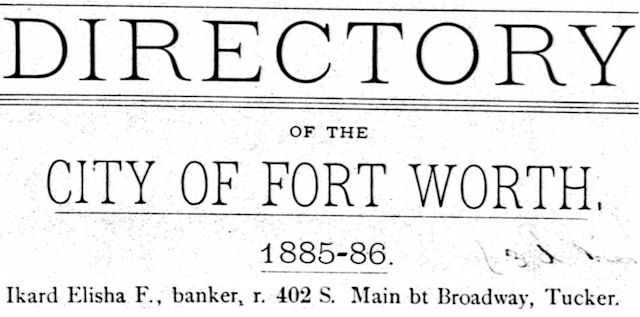

By 1884 long gone for E. F. Ikard were the days of building a log cabin with a buffalo-hide roof. At the top of Tucker’s Hill on Fort Worth’s South Main Street he built a three-story mansion on a large lot. His hilltop neighbor to the east was William Bonaparte Tucker, known as the “father of the South Side.” Ikard lived in Fort Worth from 1884 to about 1891. He then moved to Oklahoma. Maps are from 1885, 1886, and 1891.

By 1884 long gone for E. F. Ikard were the days of building a log cabin with a buffalo-hide roof. At the top of Tucker’s Hill on Fort Worth’s South Main Street he built a three-story mansion on a large lot. His hilltop neighbor to the east was William Bonaparte Tucker, known as the “father of the South Side.” Ikard lived in Fort Worth from 1884 to about 1891. He then moved to Oklahoma. Maps are from 1885, 1886, and 1891.

(Among later residents of the Ikard block would be merchant George Monnig and Leonard’s Department Store sidewalk singing street missionaries Herman and Sylvia Douglas.)

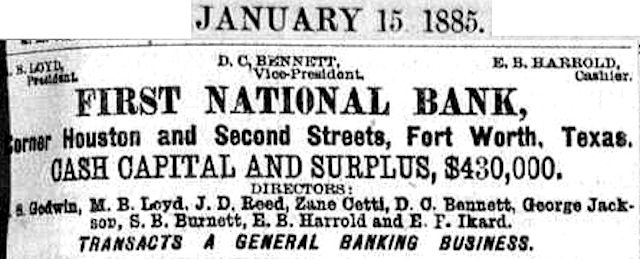

Ikard also was a director of First National Bank. Other cattlemen who were directors were Burnett, Loyd, and Harrold.

Ikard also was a director of First National Bank. Other cattlemen who were directors were Burnett, Loyd, and Harrold.

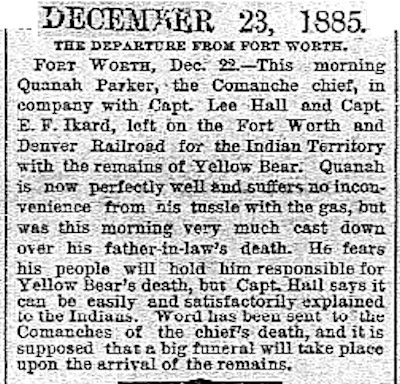

In 1885 Ikard accompanied Quanah Parker as the body of Yellow Bear was returned to the Indian Territory after a fatal accident in Fort Worth.

In 1885 Ikard accompanied Quanah Parker as the body of Yellow Bear was returned to the Indian Territory after a fatal accident in Fort Worth.

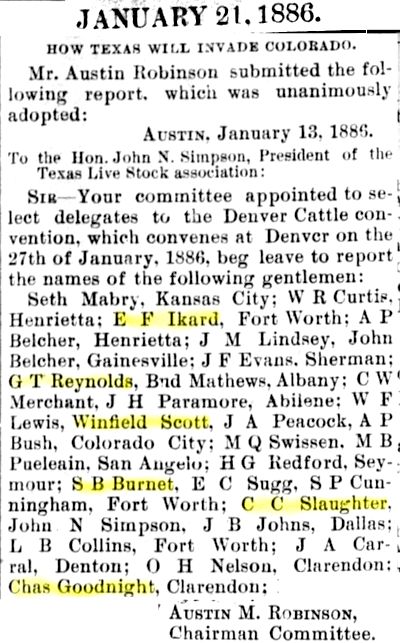

In 1886 Ikard, along with other prominent local cattlemen, was a delegate to a convention in Denver. C. C. Slaughter, the “cattle king of Texas” and the biggest individual taxpayer in Texas in his heyday, was the brother of Fort Worth cattleman John Bunyan Slaughter.

In 1886 Ikard, along with other prominent local cattlemen, was a delegate to a convention in Denver. C. C. Slaughter, the “cattle king of Texas” and the biggest individual taxpayer in Texas in his heyday, was the brother of Fort Worth cattleman John Bunyan Slaughter.

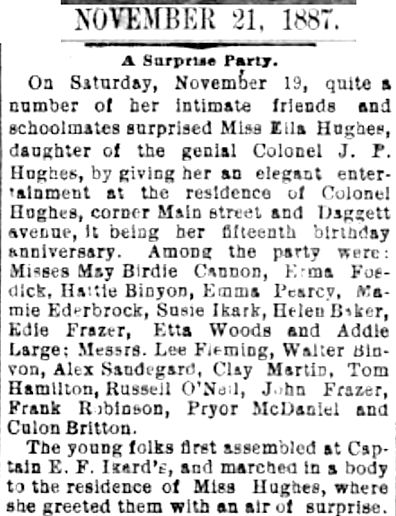

In 1887 E. F. Ikard was forty-seven years old. His world had changed even more. Now he was a banker who rubbed elbows and assets with other bankers. Now he lived in a mansion on a hill. Now he had a thirteen-year-old daughter who attended birthday parties in a town that had railroads and streetcars and nary a “depredation.”

In 1887 E. F. Ikard was forty-seven years old. His world had changed even more. Now he was a banker who rubbed elbows and assets with other bankers. Now he lived in a mansion on a hill. Now he had a thirteen-year-old daughter who attended birthday parties in a town that had railroads and streetcars and nary a “depredation.”

Among the birthday party celebrants were a few with familiar surnames of early Fort Worth: Binyon, Fosdick. Addie (Ada) Large three years later would be a heroine of the Spring Palace fire.

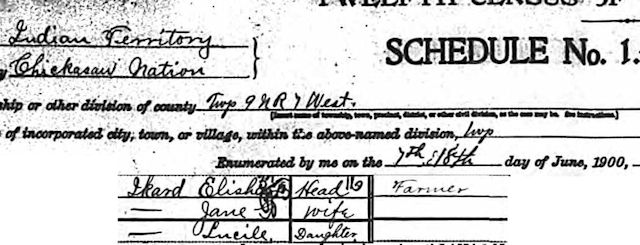

Three years later Ikard was living in the Indian Territory. Oklahoma Territory and Indian Territory would not merge as the state of Oklahoma until 1907.

Three years later Ikard was living in the Indian Territory. Oklahoma Territory and Indian Territory would not merge as the state of Oklahoma until 1907.

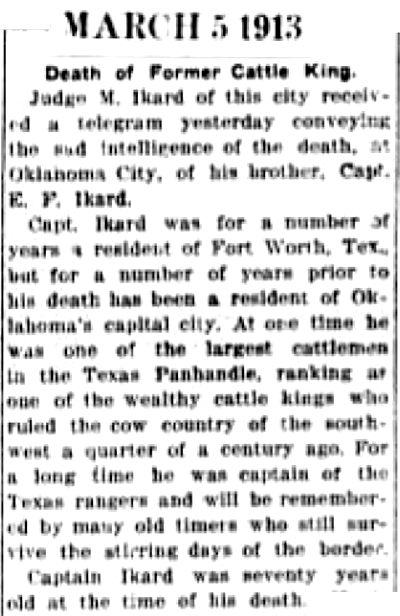

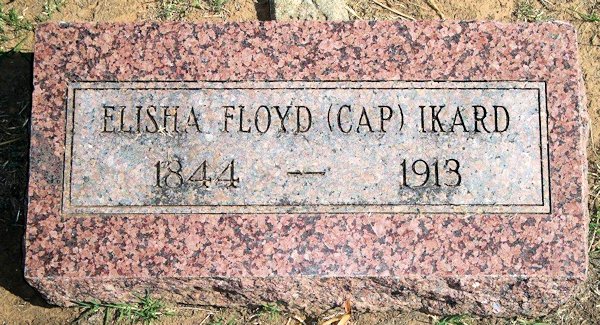

Elisha Floyd Ikard died in Oklahoma City in 1913. He is buried there.

Elisha Floyd Ikard died in Oklahoma City in 1913. He is buried there.

Footnotes: Dr. Milton Ikard represented Parker County in the Texas legislature during the Civil War.

In 1896 William S. Ikard was a founder of the Fort Worth stock show.

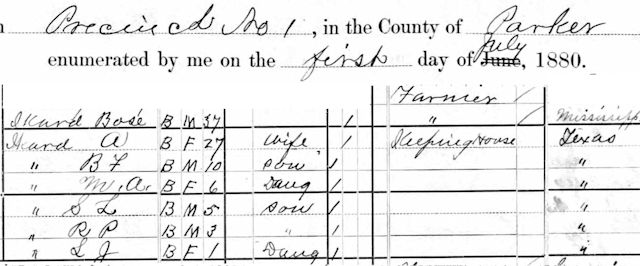

And there’s another Ikard of historical significance: Dr. Ikard had a slave named “Bose Ikard” (Bose probably adopted the surname of his owner). Brothers Elisha Floyd and William S. Ikard and Bose were born within three years of each other and grew up together. The Ikards brought Bose with them to Parker County in 1855. Bose became a proficient cowboy and scout. As a free man after the war, Bose helped Charles Goodnight and Oliver Loving blaze their cattle trail. The African-American cowboy Deets in Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove is said to be based on Bose Ikard.

And there’s another Ikard of historical significance: Dr. Ikard had a slave named “Bose Ikard” (Bose probably adopted the surname of his owner). Brothers Elisha Floyd and William S. Ikard and Bose were born within three years of each other and grew up together. The Ikards brought Bose with them to Parker County in 1855. Bose became a proficient cowboy and scout. As a free man after the war, Bose helped Charles Goodnight and Oliver Loving blaze their cattle trail. The African-American cowboy Deets in Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove is said to be based on Bose Ikard.

Your article about my Ikard family is one of very few that represents my family in an honest description. I am the great granddaughter of William Susan Ikard and Kate Lewis Ikard.

I am blessed with so many family stories that my Grandmother Emma John Ikard Smith would tell me getting ready for nap time so many years ago. Why do you have such a keen interest in the Ikard name? All the best….. Elisa

Thank you, Elisa. Your great-grandfather was an important part of Fort Worth history.