Every house has a history—a story to tell of its occupants past and present. Most of those stories are mundane; a few are decidedly unmundane.

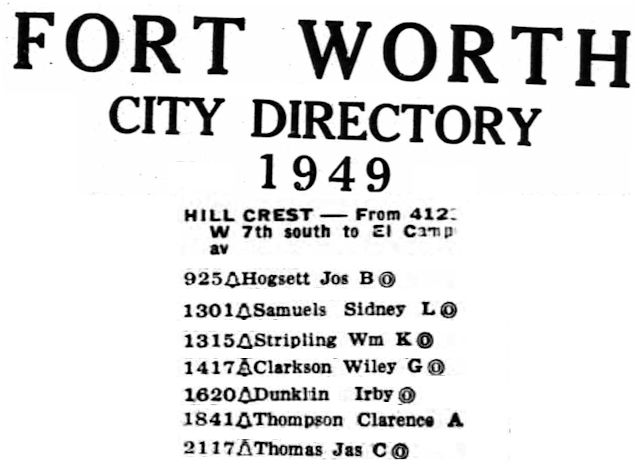

Take, for example, the house at 2117 Hillcrest Street on the West Side. Who lived there? What stories could the house tell? Let’s turn back the clock to 1949 and take a stroll down genteel Hillcrest Street.

Here are a few of the addresses and the occupants therein:

Here are a few of the addresses and the occupants therein:

925 Joseph Bratcher Hogsett, who served forty-one years on the Tarrant County water board

1301 Sidney L. Samuels, attorney who testified against serial killer Dr. Henry Howard Holmes

1315 William K. Stripling of the department store family

1417 Wiley G. Clarkson, architect

1620 Irby Dunklin, chief justice of the Second Court of Civil Appeals

1841 Clarence A. Thompson (Mr. T), Poly High School principal

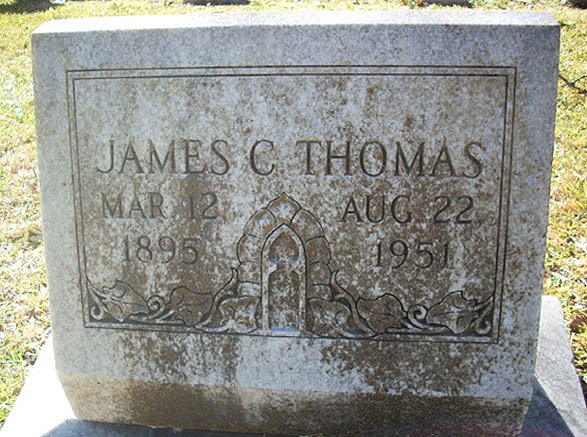

2117 James C. Thomas, hitman

At this point, feel free to execute a cartoon-like double-take.

Hitman?

James Clyde Thomas was born in 1895 in McLennan County. As a young man he worked as a fireman, a hotel clerk, a house painter.

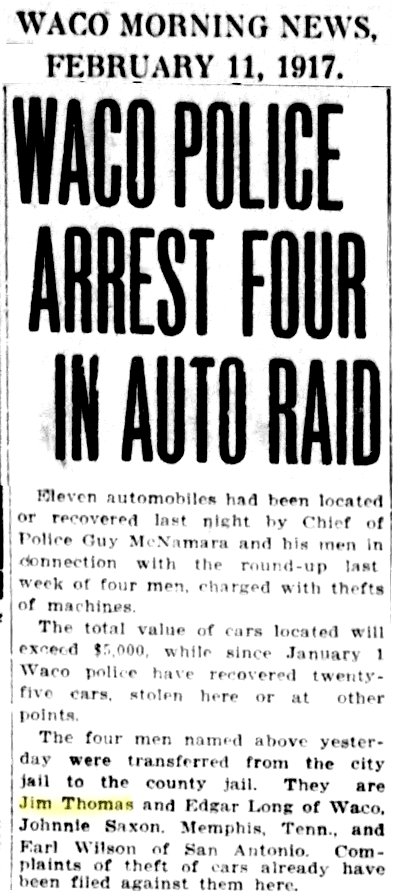

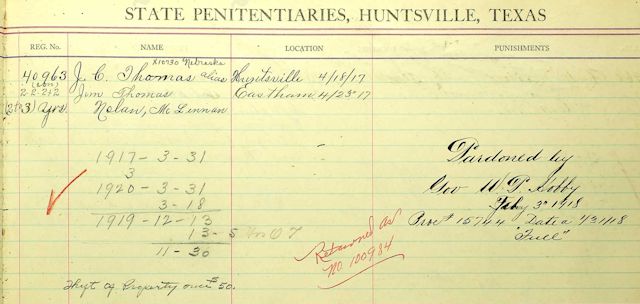

Then Thomas swerved off the straight and narrow. In 1917 he was one of four men charged in Waco with stealing twenty-five automobiles. He was sentenced to three years in the Texas penitentiary.

Then Thomas swerved off the straight and narrow. In 1917 he was one of four men charged in Waco with stealing twenty-five automobiles. He was sentenced to three years in the Texas penitentiary.

With a pardon in 1918 and Prohibition in 1920, Thomas turned to selling bootleg whiskey, making $1,000 a week ($14,000 today). In 1926 during the oil boom in west Texas he moved to Borger to sell bootleg whiskey to oil field workers.

He sold “millions of gallons” in the 1920s, he later said, and eventually was worth $75,000 ($1 million today).

Then came the Great Depression, the era of daring bank robberies.

Then came the Great Depression, the era of daring bank robberies.

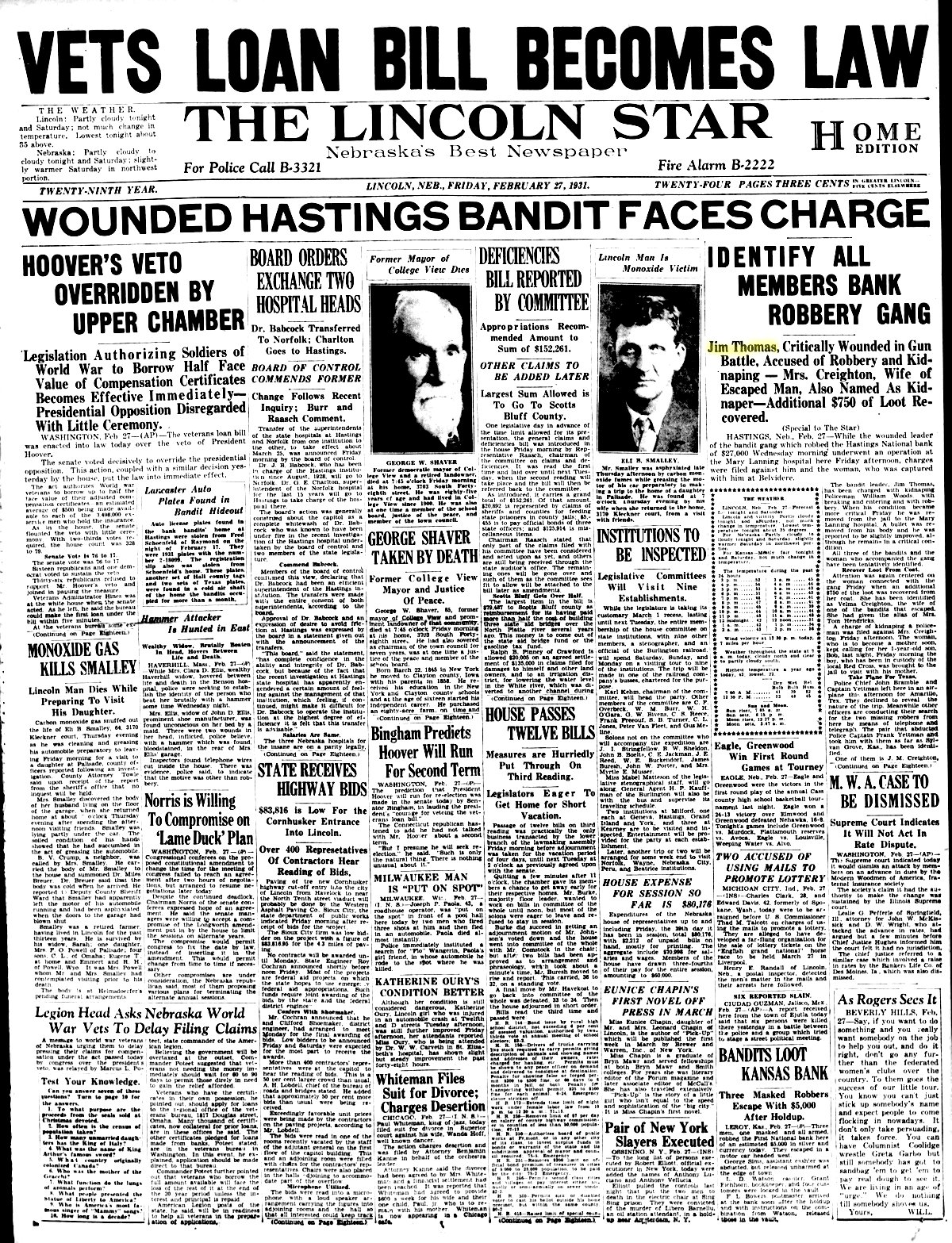

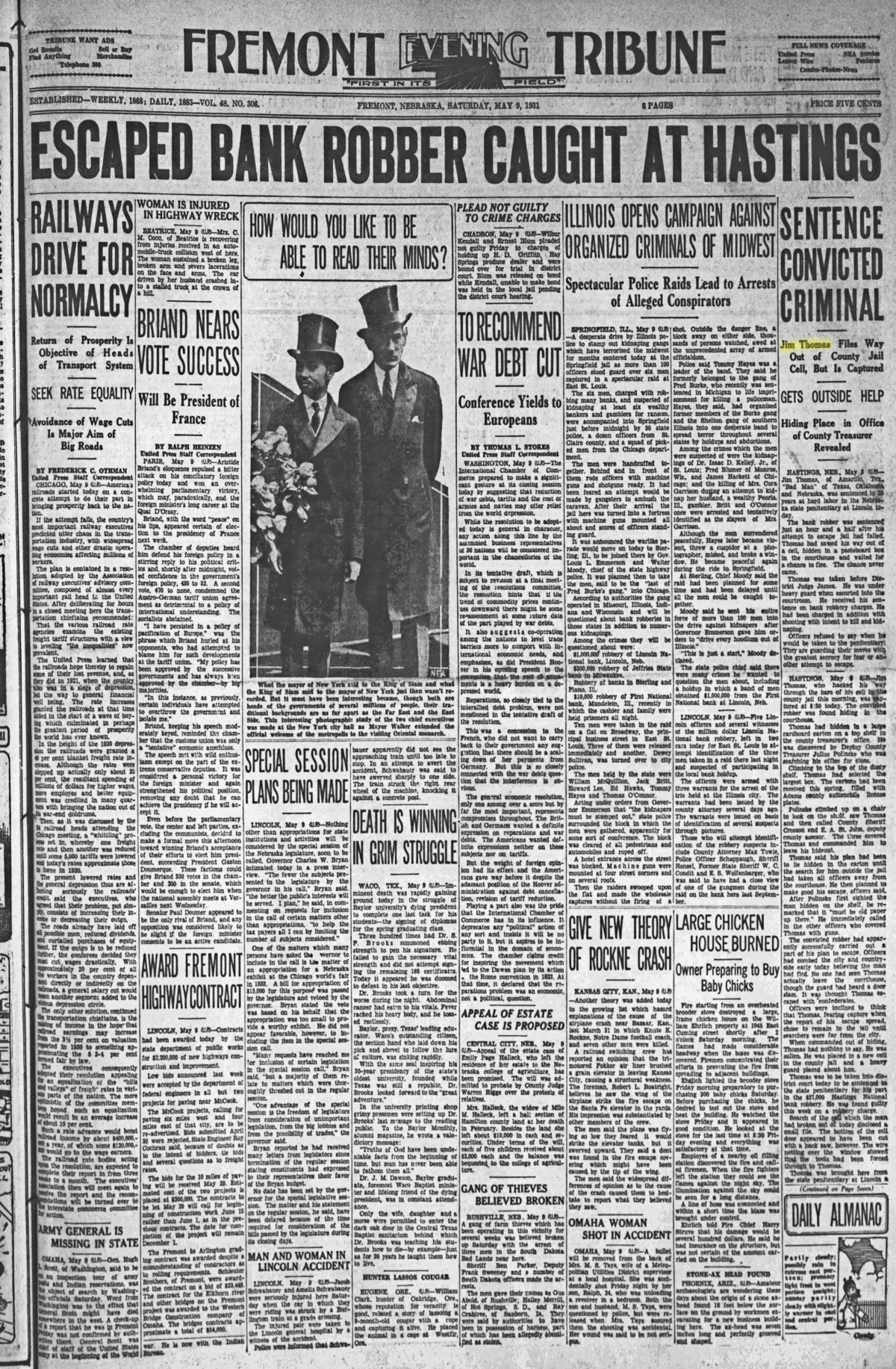

Before dawn on February 25, 1931 three masked men broke a window at the rear of Hastings National Bank in Nebraska and entered. They waited in darkness until the janitor arrived after 6 a.m. They forced the janitor to describe what other bank employees looked like and when they would arrive for work.

As each employee arrived, he or she was marched to the basement at gunpoint and bound and gagged—thirteen people in all. The robbers forced one bank official to open the bank vault, which they emptied of $27,000 ($450,000 today).

Before the robbers left the bank, one of them started a fire in the bank’s furnace.

“I don’t want the [bank] president and his helpers to be cold when they come this morning,” he told the janitor.

Three days later police raided the robbers’ hideout. At the hideout were three men—including Jim Thomas—and the wife of robber Jimmy Creighton. Velma Creighton, twenty-four, was pregnant and had with her a one-year-old child.

During a gunfight with police Thomas was wounded, and the robbers captured two of the policemen.

In the robbers’ rush to escape, Mrs. Creighton and her child climbed into the wrong getaway car and escaped with Thomas, not her husband. Jimmy Creighton and the third robber escaped in another car, taking with them the two policemen, who were later released unharmed.

Police captured Thomas and Mrs. Creighton when the pair stopped to get medical attention for Thomas’s gunshot wound.

Thomas was hospitalized and later convicted of bank robbery.

Recovered from his bullet wound and in jail awaiting sentencing, on May 9, 1931 Thomas sawed his way out of his jail cell with a file. He was found hiding in a cardboard box in a closet in the courthouse and captured. An hour and a half later, under heavy guard, he was sentenced to twenty-five years in the Lincoln, Nebraska state prison.

Recovered from his bullet wound and in jail awaiting sentencing, on May 9, 1931 Thomas sawed his way out of his jail cell with a file. He was found hiding in a cardboard box in a closet in the courthouse and captured. An hour and a half later, under heavy guard, he was sentenced to twenty-five years in the Lincoln, Nebraska state prison.

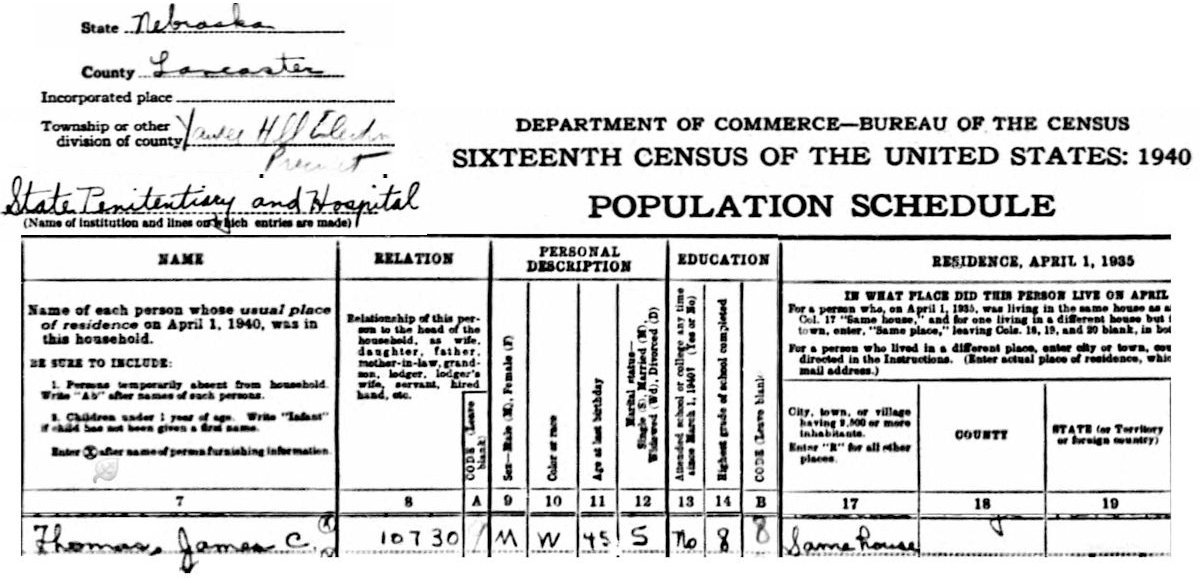

The 1940 census found Thomas still in the prison at Yankee Hill. Thomas worked as a surgical nurse in the prison hospital. There he picked up a rudimentary knowledge of anesthetics, a knowledge he would find useful three years later.

The 1940 census found Thomas still in the prison at Yankee Hill. Thomas worked as a surgical nurse in the prison hospital. There he picked up a rudimentary knowledge of anesthetics, a knowledge he would find useful three years later.

Later in 1940 his sentence was commuted for good behavior.

Come 1941 Jim Thomas was back in west Texas, and for the rest of the decade newspapers would bleed a lot of ink over three names: Thomas, Newton, and Hunt.

First Jim Thomas was charged with armed robbery of a poker game in Lubbock. He was freed on bond.

In January 1942 he was taken from Waco to Canyon to be charged with robbing the First National Bank of Canyon in 1931.

On March 17, 1942 he was taken to Lubbock by Texas Rangers to face charges in the poker game robbery. He was again freed on bond.

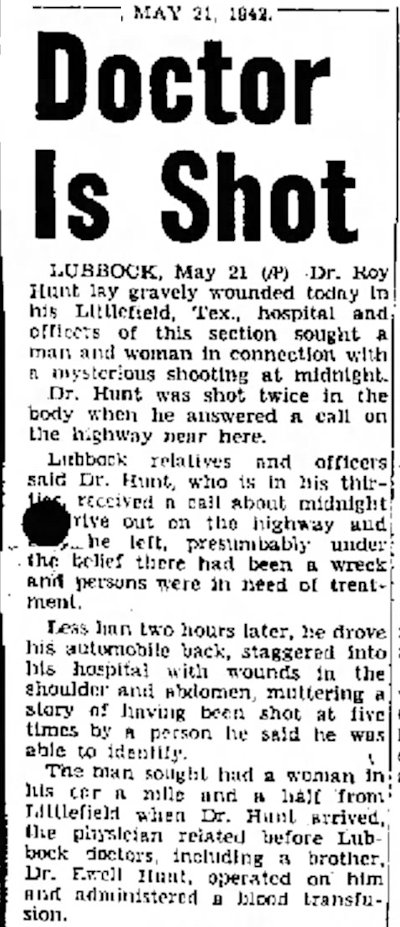

Then, on May 21, 1942 west Texans read in their newspapers about a seemingly unrelated crime—one not committed by Jim Thomas.

Then, on May 21, 1942 west Texans read in their newspapers about a seemingly unrelated crime—one not committed by Jim Thomas.

Dr. Roy Hunt of Littlefield near Lubbock received a phone call about midnight. A woman’s voice said that a car wreck had occurred on the Littlefield-Lubbock highway and that his medical assistance was needed. The woman gave Hunt an address on the highway.

When Hunt arrived at the isolated address, he saw a parked car but no evidence of a wreck.

Sitting in the car was a woman.

“You sure are a hard man to get,” she said to Hunt.

She invited Hunt into the back seat.

Then a man stepped out of the darkness.

“Don’t you know that’s a married woman?” the man asked and then fired five shots at Hunt, hitting him twice.

Seriously wounded, Hunt escaped into the darkness as his assailant tried to find him using a spotlight on his car. Hunt dragged himself back to his own car and drove to his sanitarium, where his brother, also a physician, performed surgery to save Hunt’s life.

Roy Hunt was able to tell police who his assailants were: Dr. and Mrs. William R. Newton of Cameron, near Temple. Hunt and his wife had known Newton and his wife during medical school and internship in the 1930s. Hunt had dated Newton’s wife before the Newtons married. But, Hunt told police, he had not seen the Newtons since 1935. Cameron and Littlefield are four hundred miles apart.

Dr. and Mrs. Newton were charged with assault to murder.

Meanwhile, wealthy Maitland Jones had become nervous on his country estate near Lubbock: He had seen a man “skulking” about his property, his dog had been poisoned, and he had been the “object of intimidation” by persons in Amarillo.

Meanwhile, wealthy Maitland Jones had become nervous on his country estate near Lubbock: He had seen a man “skulking” about his property, his dog had been poisoned, and he had been the “object of intimidation” by persons in Amarillo.

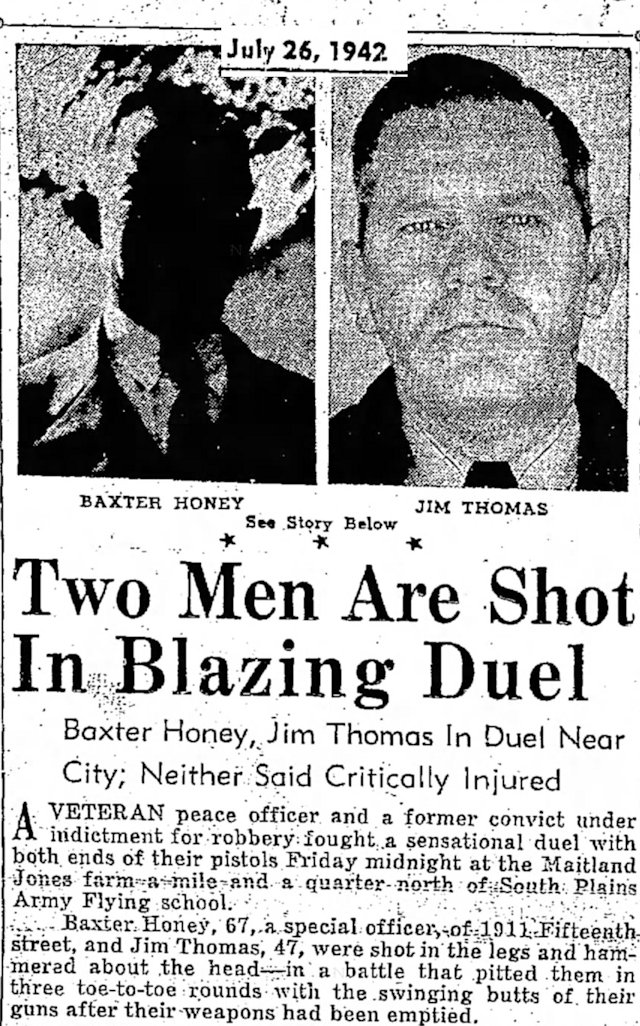

So, he hired veteran policeman Baxter Honey as a guard.

At midnight on July 24, 1942 Honey saw a car stop on the Plainview-Lubbock highway near the Jones estate. He heard a door slam.

Fifteen minutes later Honey saw a man in some brush on the Jones property. Honey drew his pistol and approached the man.

Suddenly a deep voice said, “Stick ’em up,” and someone began shooting at Honey. Honey returned the fire. He could not see in the dark, so he aimed at the muzzle flashes.

Honey and his assailant emptied their pistols at each other. Then the assailant charged out of the brush and attacked Honey with his fists.

“The fellow was strong and tough,” Honey later said. “He hit me a blow here on the right side of my forehead that set me down on my hunkers.”

Both men staggered apart, caught their breath, and resumed the battle, hitting each other with the butts of their empty pistols.

“He came in like a bull, and we started swinging our pistols at each other. . . . I hit him on the head with my gun—and down he went on his hunkers that time.”

Finally both men, like wounded stags, were too exhausted and battered to continue. The assailant limped away into the darkness. Baxter Honey was too weak to pursue.

Mrs. Jones phoned police. When police arrived they found plenty of blood but no assailant.

Five hours later police received another phone call from the Jones estate. A man was lying in the rain and crying for help.

It was Jim Thomas.

Both men were hospitalized. Honey, sixty-seven, had been shot once in the leg. Thomas, forty-seven, had been shot twice in the leg. Both had lost a lot of blood.

Thomas would not tell police why he had been on the Jones property and had shot Baxter Honey.

Thomas was convicted of assault to murder and sentenced to five years in Huntsville penitentiary.

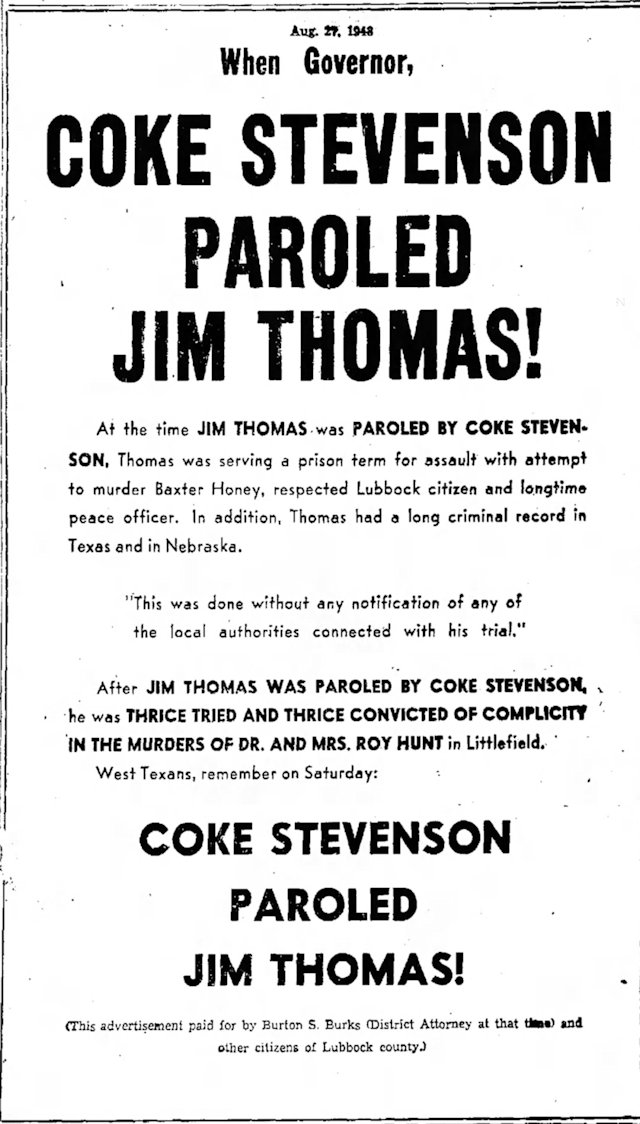

But one of his leg wounds flared up while he was in prison, and doctors said his life was in jeopardy. Governor Coke Stevenson granted Thomas a medical parole, and on March 13, 1943 Thomas was released into the custody of the Galveston parole board to undergo surgery.

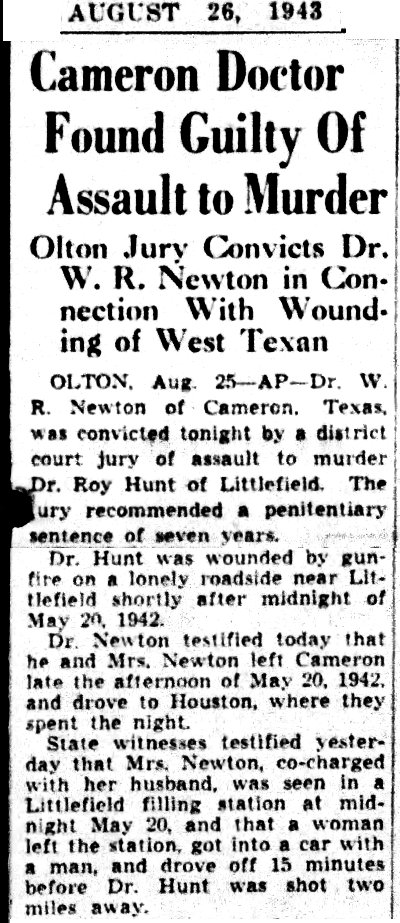

Meanwhile in 1943 Dr. Newton went on trial for assault to murder Dr. Hunt. Mrs. Newton’s trial was delayed for medical reasons. Witnesses for the state testified that they had seen Mrs. Newton and a man leave a gas station in a car fifteen minutes before Dr. Hunt was shot. The gas station was two miles from the crime scene.

Meanwhile in 1943 Dr. Newton went on trial for assault to murder Dr. Hunt. Mrs. Newton’s trial was delayed for medical reasons. Witnesses for the state testified that they had seen Mrs. Newton and a man leave a gas station in a car fifteen minutes before Dr. Hunt was shot. The gas station was two miles from the crime scene.

The Newtons claimed they had been in Houston when Hunt was shot.

Dr. Newton was convicted of assault to murder and sentenced to seven years in prison, but the court of criminal appeals reversed the conviction and ordered a new trial.

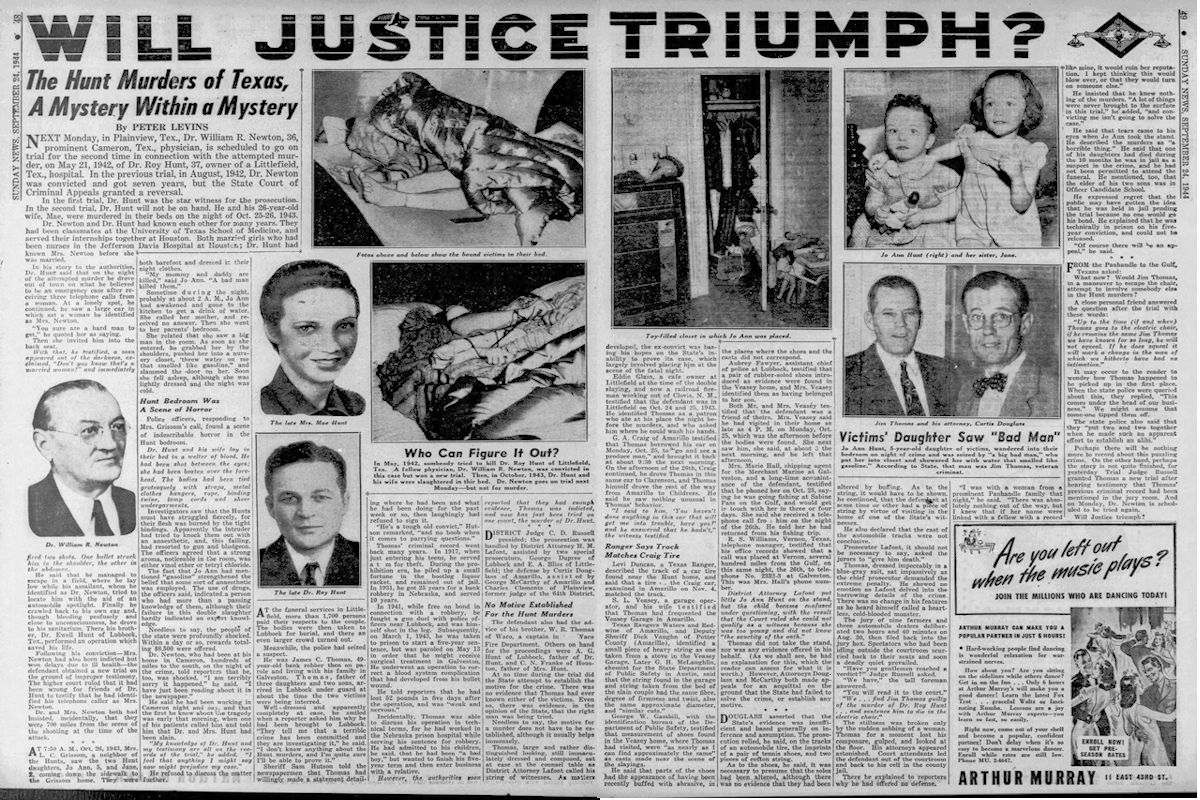

Meanwhile back at Dr. Roy Hunt’s home in Littlefield, about 2 a.m. on the morning of October 26, 1943 the Hunts’ daughter Jo Ann, six, had gotten out of bed to get a drink of water in the kitchen. Calling to her mother but getting no response, Jo Ann went to her parents’ bedroom. When she entered, a stranger who wore a mask and gloves and had “ugly round feet” grabbed her by the shoulders, pushed her into a closet, doused her with “water . . . that smelled like gasoline,” and slammed the closet door.

She soon fell asleep.

When Jo Ann awoke at 7:50 a.m. what she saw in her parents’ bedroom caused her to grab her sister Jane, two, and rush next door to the neighbors, Mrs. and Mrs. L. C. Grissom.

“My mommy and daddy are killed,” Jo Ann told Mrs. Grissom. “A bad man killed them.”

Police responding to Mrs. Grissom’s phone call found a scene “so horrible as to defy description.”

Dr. and Mrs. Hunt were dead. He had been shot between the eyes and beaten. She had been beaten to death. The Hunts had been gagged, and their bloody bodies had been bound together on the bed with twine, electrical wire, coat hangers, even Mrs. Hunt’s lingerie.

Investigators said the killer had entered the house through a window of the two daughters’ bedroom.

Daughter Jo Ann’s memory of “water . . . that smelled like gasoline” and the smell of anesthetic in the bedroom—either vinyl ether or tetrachloride—led investigators to theorize that the killer had first tried to subdue the Hunts with anesthetic. When that failed—there was evidence of a fierce struggle by the Hunts—the killer had resorted to a gun and a blunt instrument.

Police said the murders were committed by a professional.

(When the Hunts were killed, Dr. Newton was awaiting his second trial for shooting Dr. Hunt in 1942.)

Investigators were coy about their evidence, but three days after the Hunt murders Jim Thomas, still on parole in Galveston, was brought to Lubbock to be questioned just as fifteen hundred mourners were attending a double funeral for Dr. and Mrs. Hunt. Thomas made a statement about his whereabouts at the time of the murders but then refused to sign it.

Investigators were coy about their evidence, but three days after the Hunt murders Jim Thomas, still on parole in Galveston, was brought to Lubbock to be questioned just as fifteen hundred mourners were attending a double funeral for Dr. and Mrs. Hunt. Thomas made a statement about his whereabouts at the time of the murders but then refused to sign it.

“He’s a tough old convict and no boob when it comes to parrying questions,” Sheriff Sam Hutson said.

In April 1944 Thomas was indicted for the murder of Dr. Hunt.

At Thomas’s trial the state did not present a motive for the murders. There was no evidence that Thomas had known the Hunts.

There was evidence that Thomas had been in the Littlefield-Lubbock area at the time of the crime—a violation of the conditions of his parole. “Red” Craig of Amarillo, a friend of Thomas, said that he had lent his car to Thomas the day before the crime and that Thomas had returned the car the day after the crime. Tire tracks found near the Hunt home matched those of the borrowed car.

Investigators also had the channel of the Canadian River diverted so that they could search for a pistol that “Red” Craig said he had thrown into the river after fearing that Thomas had “borrowed it.”

No pistol was found.

Expert witnesses testified that the two victims were bound by a left-handed person. Thomas was left-handed.

A Galveston woman testified that Thomas had phoned her on October 23 to say he was going fishing at Sabine Pass on the gulf. On October 26, she said, Thomas phoned her again to tell her he had returned to Galveston. A telephone exchange operator in Vernon testified that on October 26 a phone call had been made to the Galveston woman’s number from Vernon—425 miles from Galveston but only 170 miles from the crime scene.

Jim Thomas did not testify.

Jim Thomas was found guilty and sentenced to death.

Jim Thomas was found guilty and sentenced to death.

Case closed, but questions remained. Had Thomas broken into the Hunt house to rob them? Had Dr. Newton hired Thomas to kill Hunt, who would be the star witness in Newton’s upcoming retrial for assault to murder? Thomas, remember, had a rudimentary knowledge of anesthetics, and Dr. Newton could supply such drugs.

After his conviction Thomas told a reporter that he had an alibi for the night of the murders: He had been with a married woman of a prominent Lubbock family. But he said he had not offered that alibi on the witness stand because he had not wanted to embarrass her.

And they say chivalry is dead!

Then began a legal table tennis match:

Ping! A month after Thomas was convicted a mistrial was declared and a second trial ordered.

Pong! Thomas was found guilty at a second trial and sentenced to death.

Ping! An appeals court ruled there was insufficient evidence to warrant a death penalty and ordered a third trial.

Pong! Thomas was found guilty at the third trial and sentenced to ninety-nine years in prison.

All this mayhem in 1944 caught the eye of the New York Daily News, which printed a two-page spread.

All this mayhem in 1944 caught the eye of the New York Daily News, which printed a two-page spread.

Meanwhile, like many career criminals, Jim Thomas was a family man. In 1945 he married his third wife, who was twenty-one. Thomas had three daughters and one son, all born before he went to prison in Nebraska in 1931.

And remember Dr. Newton? In 1946 he stood trial a second time for assault to murder Dr. Hunt (who had been killed by Thomas) in 1942. Newton was found guilty and sentenced to two years in prison. He served one year before being paroled.

Ping! In 1947 an appeals court overturned Jim Thomas’s third trial and ordered a fourth trial.

In 1948 supporters of Lyndon Johnson evoked the name of Jim Thomas as Johnson and Coke Stevenson sought the nomination in the Democratic primary in the race for a U.S. Senate seat. Johnson won the seat.

In 1948 supporters of Lyndon Johnson evoked the name of Jim Thomas as Johnson and Coke Stevenson sought the nomination in the Democratic primary in the race for a U.S. Senate seat. Johnson won the seat.

By 1948 Fort Worth was entering its era of gangland violence. And Jim Thomas, free on bond while awaiting that fourth trial, made himself right at home here.

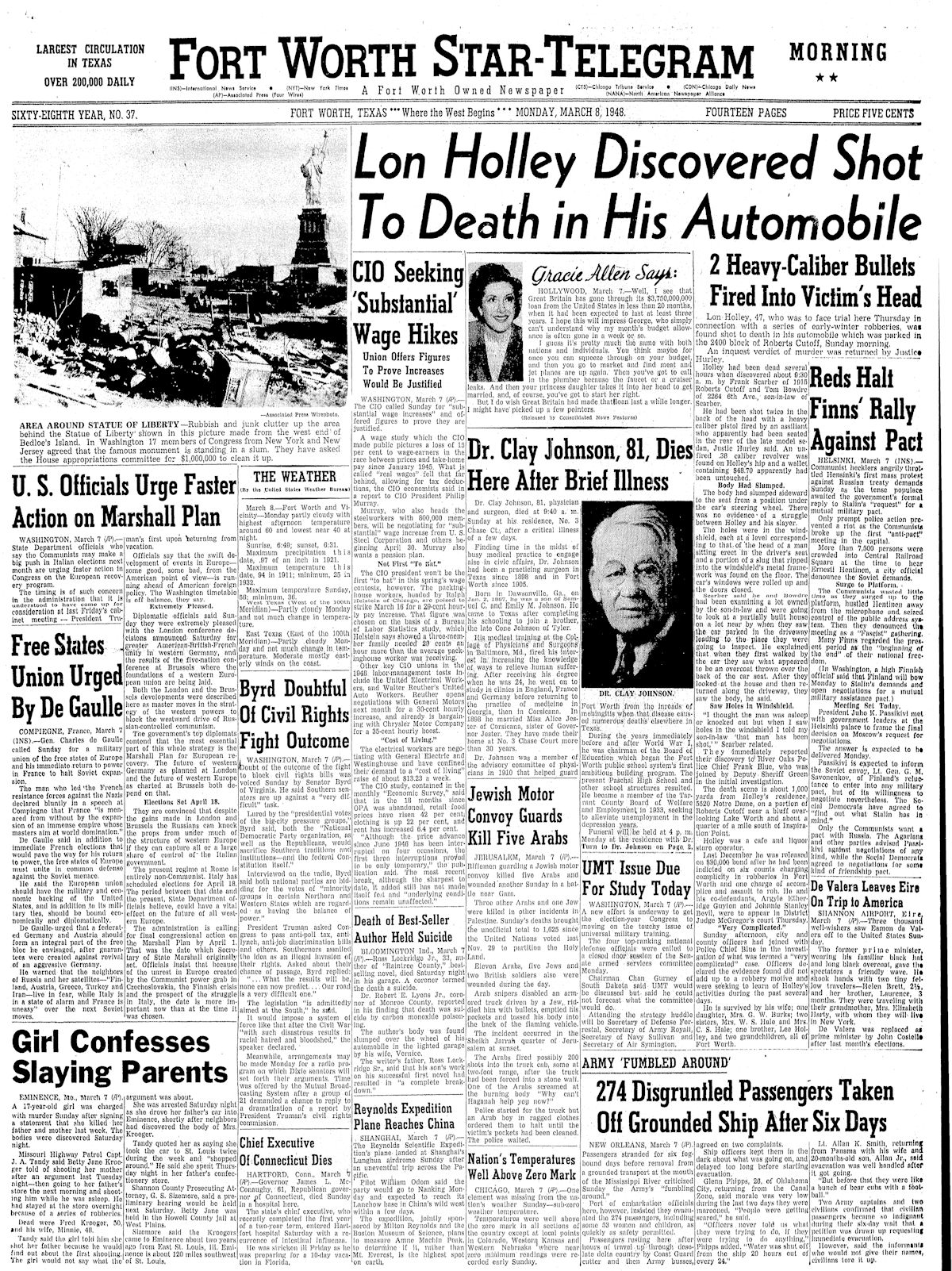

By the time Fort Worth gangland figure Lon Holley was “taken for a ride” in 1948, Thomas had moved to Fort Worth and was living at 2117 Hillcrest Street.

By the time Fort Worth gangland figure Lon Holley was “taken for a ride” in 1948, Thomas had moved to Fort Worth and was living at 2117 Hillcrest Street.

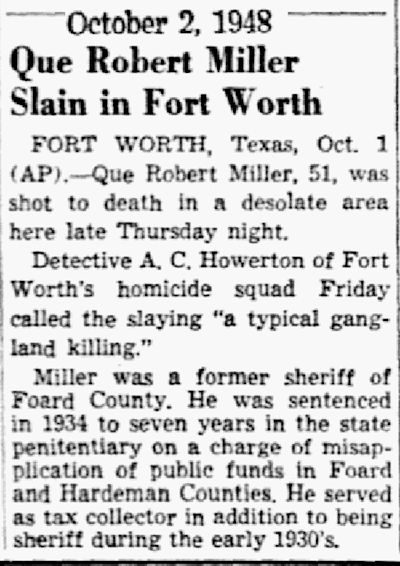

Thomas was questioned in the Holley murder but not charged.

Holley was killed three days before he was to stand trial for six robberies. He was killed less than a mile from his house near Lake Worth.

On the night Holley was killed, he had received a phone call. As Holley left his house he told his wife he was going to meet a man who would take him to see another man. Holley told his wife that if he was not back by midnight, “You will know something has happened.”

He gave her the names of two gangsters: Frank Cates and Jim Thomas.

Police theorized that Thomas had killed Holley either because Holley knew too much about the Hunt murders or because Thomas feared that Holley would turn state’s evidence about a Glen Rose bank robbery in which both men were suspects. But police did not have enough evidence to arrest Thomas in the Holley murder.

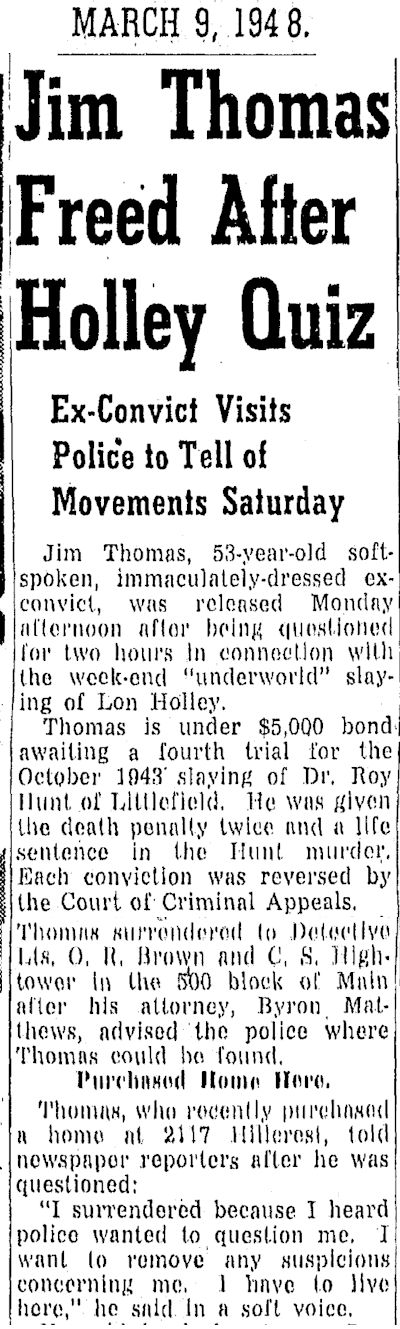

Apparently Thomas’s defense attorney, Byron Matthews (later a district judge), had sold him the house on Hillcrest.

Apparently Thomas’s defense attorney, Byron Matthews (later a district judge), had sold him the house on Hillcrest.

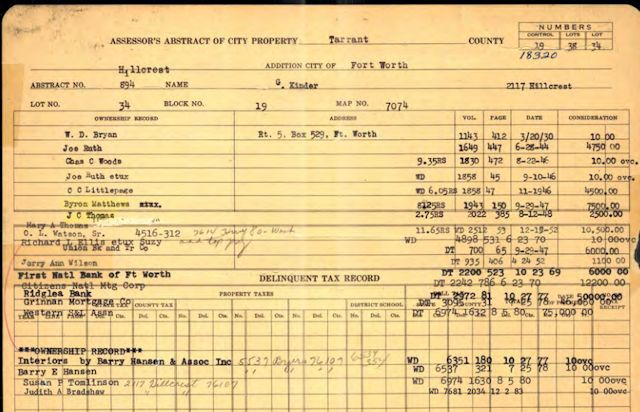

Thomas was questioned a few months later when Que Miller, like Holley, was “taken for a ride”: shot to death in his automobile in a secluded area. Miller was a former sheriff who had turned to crime.

Thomas was questioned a few months later when Que Miller, like Holley, was “taken for a ride”: shot to death in his automobile in a secluded area. Miller was a former sheriff who had turned to crime.

In 1949 Jim Thomas was questioned in the car-bombing that no doubt was intended to kill Herbert “The Cat” Noble in Dallas but instead killed Noble’s wife Mildred. Noble had earlier left their home in his wife’s car, causing her to take his. A charge of nitroglycerin had been connected to his car’s generator.

In 1949 Jim Thomas was questioned in the car-bombing that no doubt was intended to kill Herbert “The Cat” Noble in Dallas but instead killed Noble’s wife Mildred. Noble had earlier left their home in his wife’s car, causing her to take his. A charge of nitroglycerin had been connected to his car’s generator.

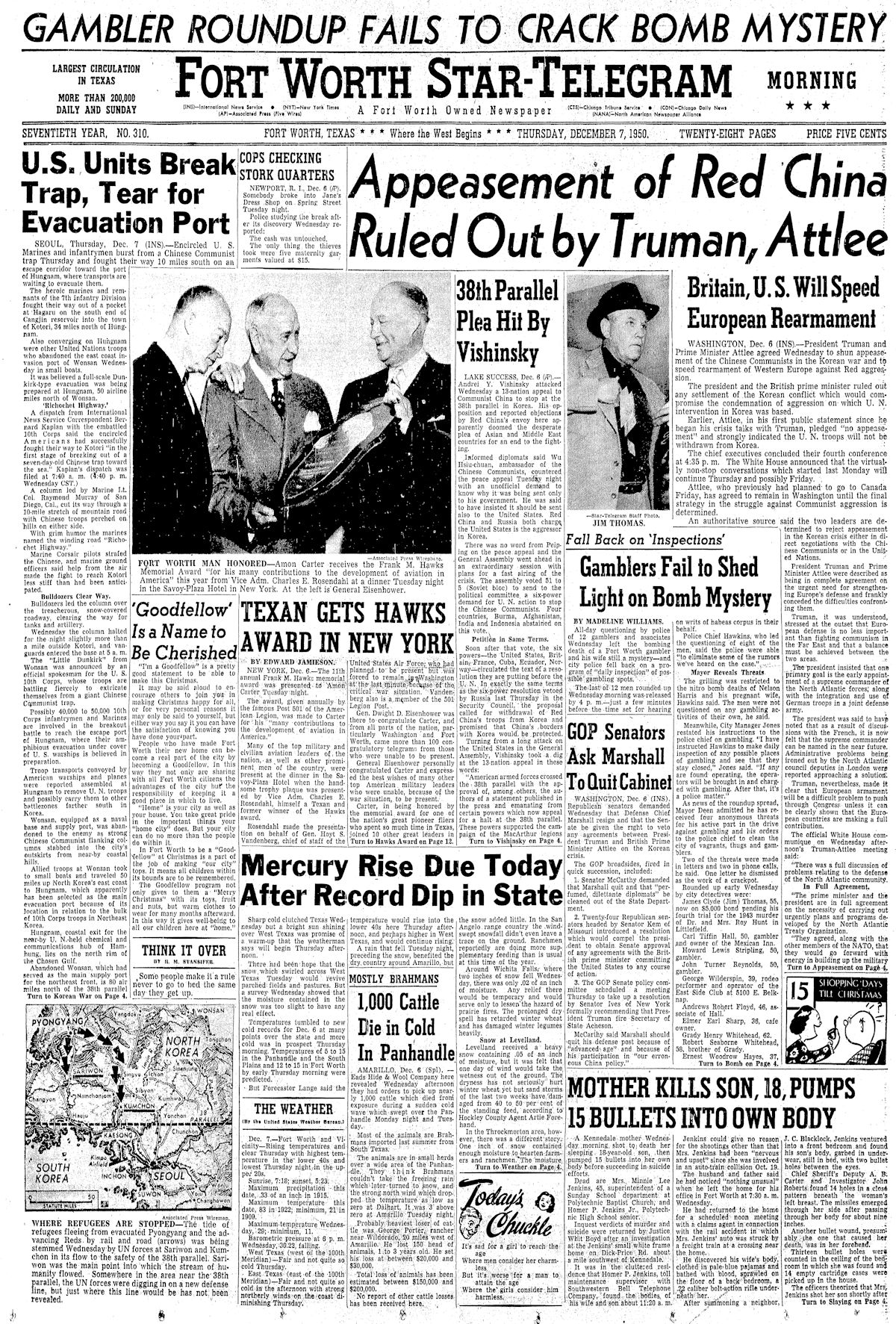

Another year, another gangland slaying: In 1950 Jim Thomas was among “the usual suspects” questioned after the Nelson Harris car-bombing.

Another year, another gangland slaying: In 1950 Jim Thomas was among “the usual suspects” questioned after the Nelson Harris car-bombing.

When The Cat finally ran out of lives on August 7, 1951 Thomas was again questioned, along with Tincy Eggleston and Jack Nesbit.

When The Cat finally ran out of lives on August 7, 1951 Thomas was again questioned, along with Tincy Eggleston and Jack Nesbit.

If the wheels of justice turned slowly for Dr. Newton (four years from crime to conviction), they positively creaked for Jim Thomas. In 1951 Thomas was still awaiting his fourth trial for the murder of Dr. Hunt, still walking the streets after being convicted three times of a crime committed eight years earlier.

Thomas would have been safer in prison.

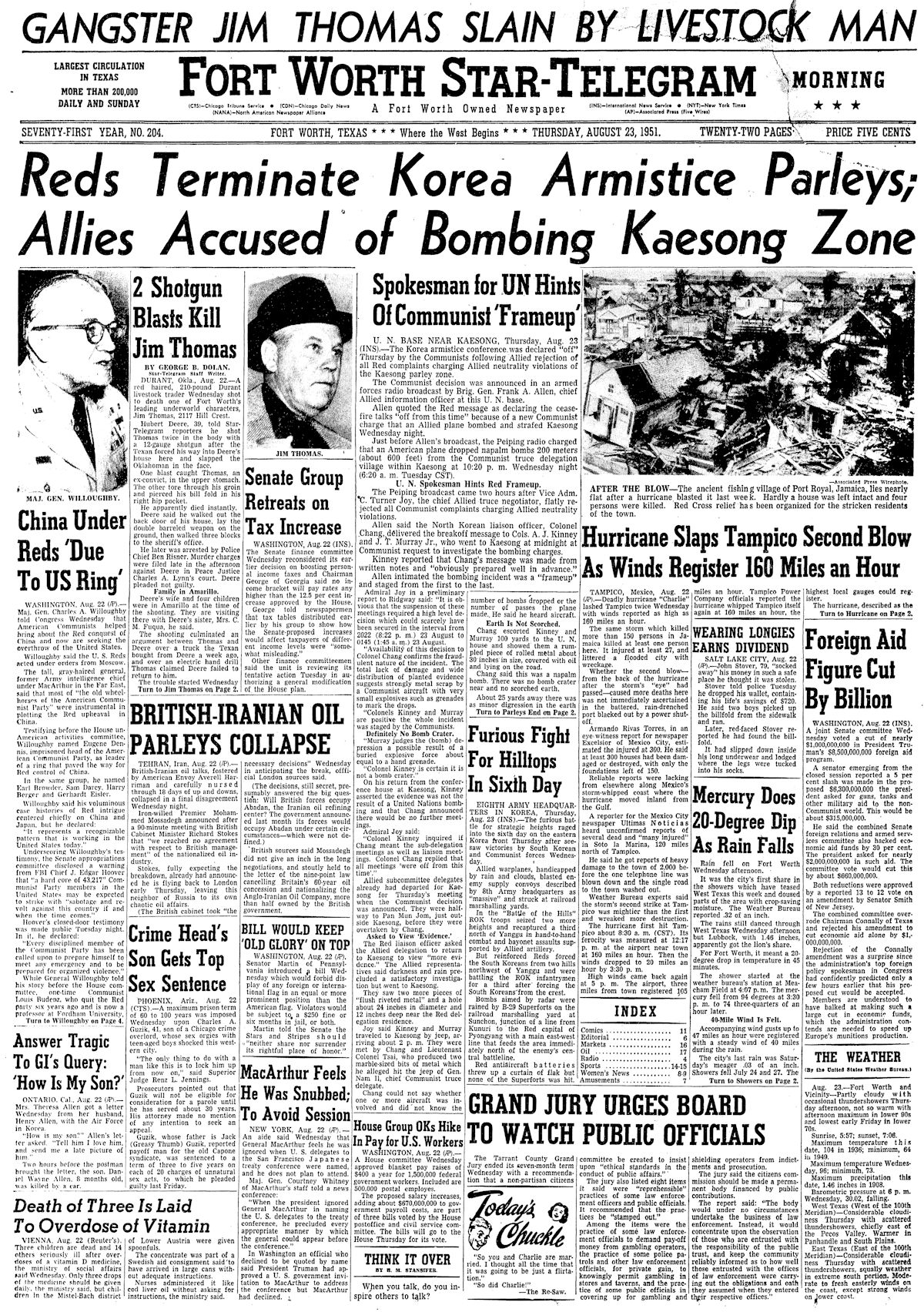

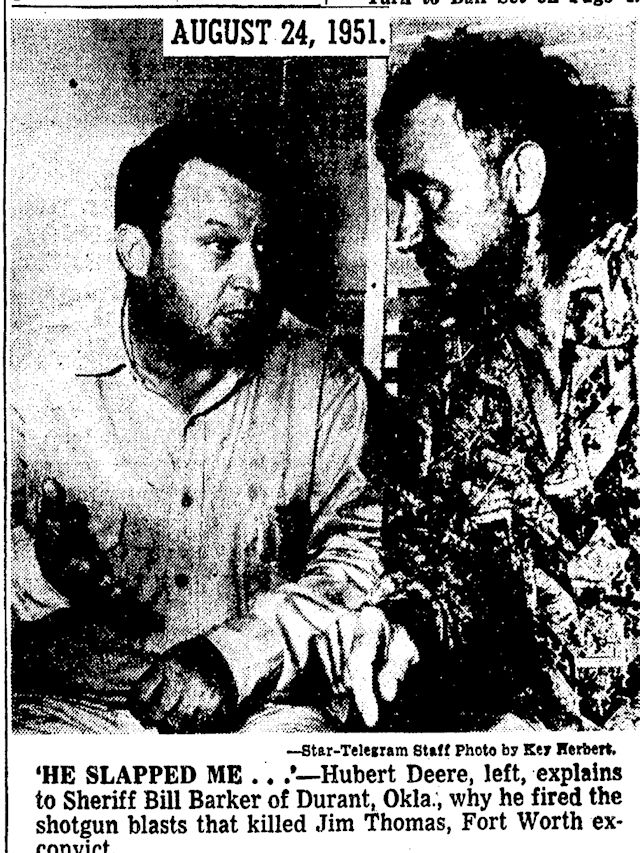

On August 22, 1951, just two weeks after the murder of Herbert Noble, in Durant, Oklahoma Hubert Deere, thirty-nine, a truck dealer, was talking with a friend on a street corner when Jim Thomas approached him.

Thomas and Deere had known each other ten years. They were friends and business associates.

But on that street corner Thomas accused Deere of misrepresenting the condition of a truck that Deere had sold to Thomas and of failing to return to Thomas an electric drill that Deere had borrowed.

“I think that drill is in your house. I’m gonna . . . come down and look for it,” Deere later quoted Thomas as saying.

Deere later told police that he warned Thomas not to come to his house.

Thomas came to his house.

Deere warned him not to come in.

He came in.

Thomas slapped Deere across the mouth.

Deere walked into the bathroom and came back with a double-barrel twelve-gauge shotgun and pulled both triggers.

He then walked out of the house, laid the shotgun on the ground, and walked three blocks to the sheriff’s office.

Thomas, heavy-set and six feet tall, soft spoken and polite, was always manicured and well dressed, usually in tailored gray suits. He drove a two-toned Cadillac convertible.

Thomas, heavy-set and six feet tall, soft spoken and polite, was always manicured and well dressed, usually in tailored gray suits. He drove a two-toned Cadillac convertible.

Neighbors on Hillcrest Street were shocked to learn details of their dead neighbor’s life. They described Thomas as a man who liked to putter in his garden, a man who did not drink, smoke, or swear.

Neighbors on Hillcrest Street were shocked to learn details of their dead neighbor’s life. They described Thomas as a man who liked to putter in his garden, a man who did not drink, smoke, or swear.

Next-door neighbor Mrs. T. J. Phelps of 2113 Hillcrest said Thomas was “very quiet” and “minded his own business.”

Mrs. C. B. Wilkerson of 2114 Hillcrest said, “He was friendly—but he never talked much.”

Law enforcement officers offered a different assessment: The world was better off without Jim Thomas.

Veteran Fort Worth police detective A. C. Howerton said, “I think he was one-half of the team that killed Lon Holley and Que Miller here in 1948. And he was a strong suspect in the killings of Nelson Harris and his wife and possibly was connected with the death of Herbert Noble’s wife in Dallas. He was one of Tarrant County’s hardest criminals.”

Police could never prove it, but they suspected that Jim Thomas and Frank Cates had worked as a team in killings such as those of Holley, Miller, and the Hunts.

As for Cates, he said Thomas was “an awfully nice fellow. You had to know Jim to appreciate him.”

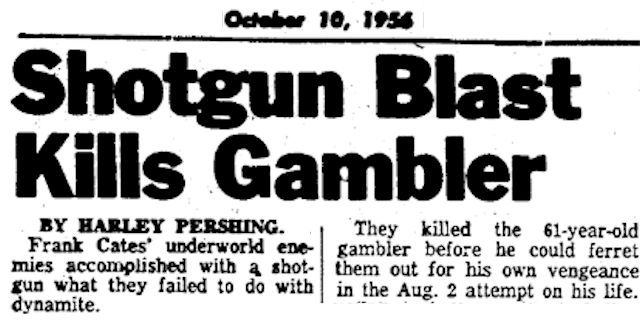

Five years later Frank Cates, too, would be killed by a shotgun.

Five years later Frank Cates, too, would be killed by a shotgun.

James Clyde Thomas, who was described by police as “one of the most cold-blooded trigger men” in the underworld, who had spent most of his adult life in prison, on parole, or free on bond while awaiting trial, who had skewed the demographics of genteel Hillcrest Street, is buried in Waco.

James Clyde Thomas, who was described by police as “one of the most cold-blooded trigger men” in the underworld, who had spent most of his adult life in prison, on parole, or free on bond while awaiting trial, who had skewed the demographics of genteel Hillcrest Street, is buried in Waco.

Fantastic read! My Aunt and Uncle lived at 2116 Hillcrest (Tom and Ruby Tullous) and I knew the neighbors on either side but we kids were never allowed to go across the street. All they would say was that Mary and Jim Thomas lived there but if we ever saw them, just wave and go about our business. Now I know why?. I’m loving your columns?

Thank you, Mary. Apparently it was not uncommon for folks like Jim Thomas to live quietly in middle-class and even upper-middle-class neighborhoods, their double life unknown to or only suspected by neighbors.

I thought, all along, that my uncle, Jim Thomas was the person described in this article. I am sorry that he caused all the problems attributed to him. And yes, he had an extremely high I.Q.so what would he have done if he had applied himself in the pursuit of helping humankind.

Life stories like that of Jim Thomas are real “there but for the grace of [insert variable] go I” stories for the rest of us.

Such an interesting piece…went to Poly, so address of Mr. T is interesting, we live not too far from there, will be interesting to see what that address looks like now!

Thanks, Shirley. I think we kids assumed that our Poly principal lived in Poly, not in . . . Arlington Heights!