Today is the first day of class for Fort Worth public schools. Each year at this time I think of my two favorite teachers.

Between the two of them they had ninety years of teaching, ninety years of spitwads and slam books, ninety years of dealing with students’ puppy love and homework-eating dogs, administrative red tape, irate parents, playground vendettas, lunchroom melodramas.

And my obsession with baseball.

Miss Alma Larson Pool

On September 7, 1960 when I walked into the sixth-grade classroom of Miss Pool for the first time, I did not know—or care—anything about her life beyond the halls of D. McRae Elementary School.

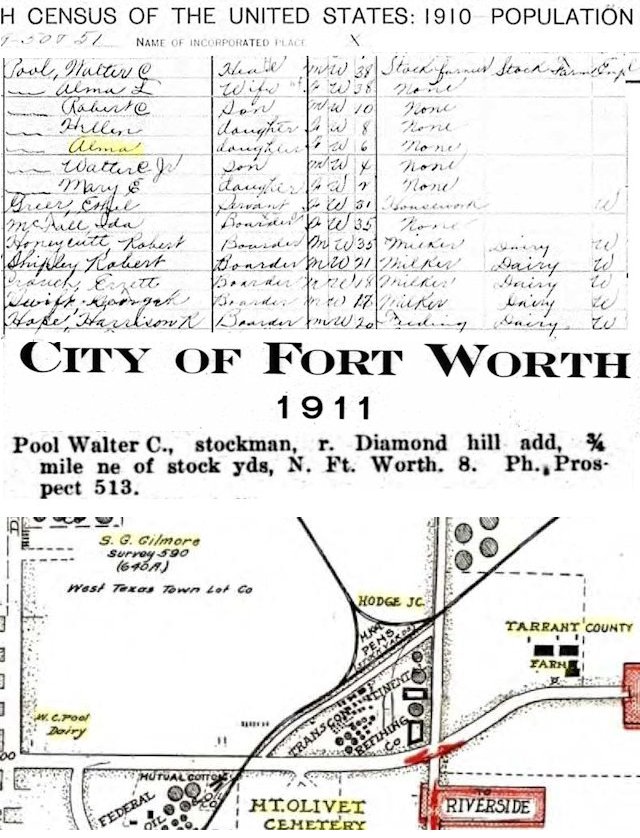

I did not know, for example, that she was born in rural Hill County, that she was named for her mother, and that her father, Walter Crawford Pool, was a rancher. And that she was born in 1903. Nineteen oh three! To a twelve-year-old in 1960, 1903 might as well have been 1492 or 1066. Too long ago to comprehend.

I also did not know that by 1910 her family had moved to Diamond Hill on the North Side and that W. C. Pool owned a dairy north of Mount Olivet Cemetery, south of the Seaborne Gilmore survey, and west of the county poor farm and Hodge Junction.

I also did not know that by 1910 her family had moved to Diamond Hill on the North Side and that W. C. Pool owned a dairy north of Mount Olivet Cemetery, south of the Seaborne Gilmore survey, and west of the county poor farm and Hodge Junction.

Miss Pool was the middle child of five children spaced two years apart.

The Pools had one servant. Even the dairy cows had servants: The Pools provided board for some of the milkers.

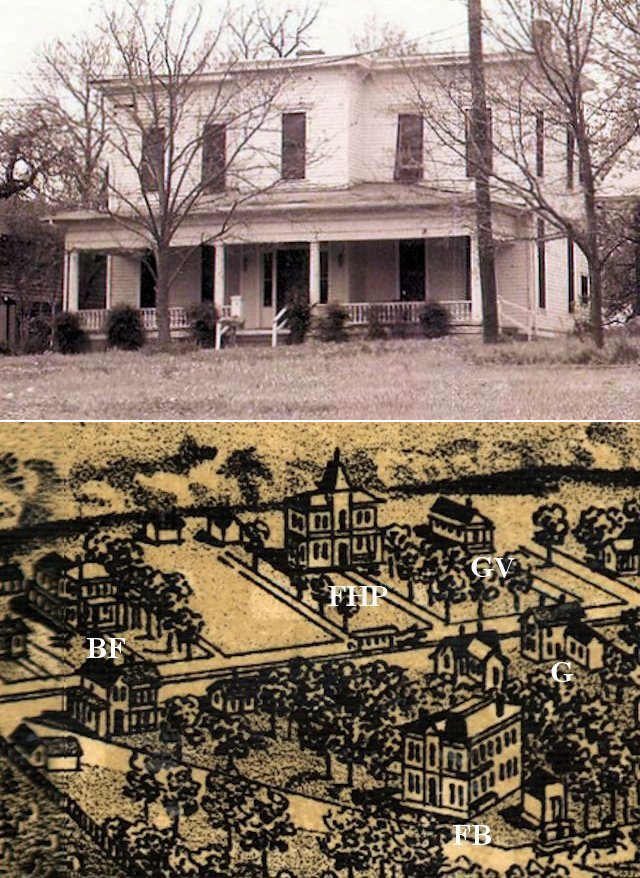

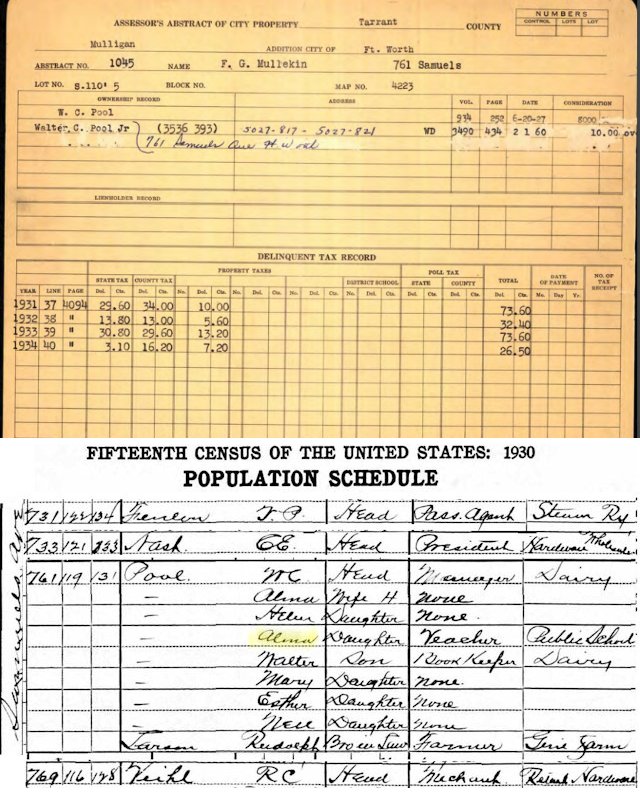

There was money in milk. In 1960 I did not know that in 1927 Miss Pool’s family moved to 761 Samuels Avenue when the street was still lined with grand homes built in the nineteenth century.

There was money in milk. In 1960 I did not know that in 1927 Miss Pool’s family moved to 761 Samuels Avenue when the street was still lined with grand homes built in the nineteenth century.

The house appears on an 1886 bird’s-eye-view map. The tower was later removed and a front porch added.

The house, which became known as the “Foster-Hodgson-Pool house,” was built in 1882. Isaac Foster was a farmer. Arthur D. Hodgson was general manager of Nash Hardware. As you will see, Samuels Avenue was Hardware Row.

These three houses on the 1886 map are still standing:

BF 731 Samuels Avenue, Bennett-Fenelon house (c. 1875). David Chapman Bennett was a vice president of Martin Bottom Loyd’s First National Bank. Thomas P. Fenelon was a passenger agent for the Santa Fe railroad.

G 761 Samuels Avenue, Getzendaner house (1880s). John Getzendaner was a stockman.

GV 769 Samuels Avenue, Garvey-Veihl house (1884). William B. Garvey was a grocer and real estate agent. Robert C. Veihl was president of Veihl-Crawford Hardware. The 1886 map shows the original house before the grand front was added about 1894.

And these two houses are gone:

FHP Foster-Hodgson-Pool, demolished in 2003.

FB brothel (1880s) of madam Frankie Brown on Cold Springs Road. The house later housed the Fort Worth Benevolent Home.

In 1960 I also did not know that by 1930 Miss Pool had become a public school teacher. She had thirty years to prepare for the class of 1961. Would that be enough time?

In 1960 I also did not know that by 1930 Miss Pool had become a public school teacher. She had thirty years to prepare for the class of 1961. Would that be enough time?

Living in the same block on the same side of Samuels Avenue overlooking the river in 1930 were ticket agent Thomas P. Fenelon, hardware man C. E. Nash, and hardware man Robert C. Veihl.

Miss Pool was even occasionally mentioned on the society pages of the Star-Telegram.

Miss Pool was even occasionally mentioned on the society pages of the Star-Telegram.

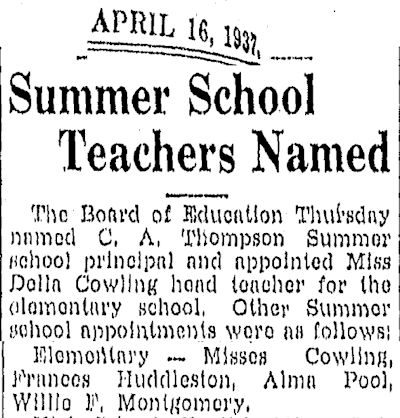

In 1937 she was a summer school teacher. Her boss? Poly High School’s future Mr. T.

In 1937 she was a summer school teacher. Her boss? Poly High School’s future Mr. T.

But I knew none of this on September 7, 1960 as I walked into my sixth-grade classroom for the first time at D. McRae Elementary School. I knew only that I was about to enter the lair of “old lady Pool.” She had a reputation among students as a humorless, unmerciful old crone, and at the end of the fifth grade when I had learned that I had been assigned to her for the sixth grade come September, I was demoralized.

But I knew none of this on September 7, 1960 as I walked into my sixth-grade classroom for the first time at D. McRae Elementary School. I knew only that I was about to enter the lair of “old lady Pool.” She had a reputation among students as a humorless, unmerciful old crone, and at the end of the fifth grade when I had learned that I had been assigned to her for the sixth grade come September, I was demoralized.

How would I survive?

Archeologists excavating her cloakroom centuries from 1960 would find nothing left of me but some Wonder Bread-fortified bones and a pair of horseshoe taps.

Of course, part of Miss Pool’s reputation could be attributed to the fact that she was one of the oldest teachers on the faculty. And yet she was actually only fifty-seven years old in 1960. But that was older than my parents, and thus she was ancient. Now I consider a person of fifty-seven to be a whippersnapper.

Of course, part of Miss Pool’s reputation could be attributed to the fact that she was one of the oldest teachers on the faculty. And yet she was actually only fifty-seven years old in 1960. But that was older than my parents, and thus she was ancient. Now I consider a person of fifty-seven to be a whippersnapper.

What happened?

We sat at desks that were made of cast iron and wood with a desktop that contained an ink well and could be lifted to store books underneath. Desks in sets of four were bolted to wooden rails.

In those days, when baseball players played their entire career with the same team, when families lived in the same house and teachers taught at the same school for years, it was not uncommon for a teacher to teach first a parent and later that parent’s child. On the first day of class teachers would walk up and down the rows of desks, checking the roll of new students: “Diane Duke . . . Danny Brown . . . Susie Lockhart . . . Lockhart . . . Lockhart . . . Susie, I had your mother.”

I remember watching Miss Pool warily on that first day of sixth grade, waiting for her to erupt and go Godzillaing around the classroom.

But she was as pleasant as could be as she checked the roll that first day in 1960.

She was biding her time, I was convinced.

Oh, she was crafty, was that old lady Pool.

As the days passed she continued to disarm us with self-deprecating humor, recalling that as a young woman she had been “as broad as a barn.”

An apt comparison for the daughter of a dairyman.

She even inadvertently triggered snickers among her adolescent students with a habit she had: She used her middle finger to push her glasses up the bridge of her nose.

Students at D. McRae Elementary were shuttled to two special teachers for the cultural classes: art and music. The rest of the teachers had to be, in baseball terms, utility infielders. My faded transcript shows that Miss Pool taught handwriting, English, Spanish, social studies, science, arithmetic, reading, spelling, and health.

I sought approval from my parents by getting good grades, so I don’t think I was much of a disappointment to Miss Pool in most subjects.

But in one subject I am sure that I, like most boys, disappointed her: handwriting.

Good handwriting requires fine motor skills. Most boys of twelve lack those. The twelve-year-old boy who can throw strikes from forty-six feet and consistently hit liners up the middle between the shortstop and second baseman can’t sign his name on a check that even his own mother would cash.

But Miss Pool’s handwriting was perfect—identical to that on the chart displayed above the blackboard in her classroom.

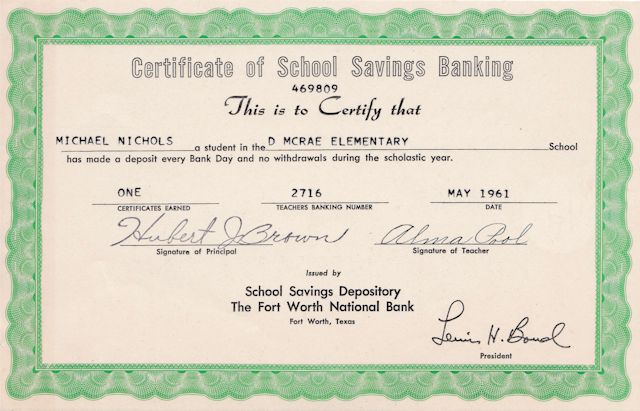

I still have three documents she signed in 1961. In each the italic lines of her A, l, m, and a are parallel, the downstroke of her l perfectly straight, the humps of her m identical.

I still have three documents she signed in 1961. In each the italic lines of her A, l, m, and a are parallel, the downstroke of her l perfectly straight, the humps of her m identical.

She wrote with a fountain pen, not a ballpoint.

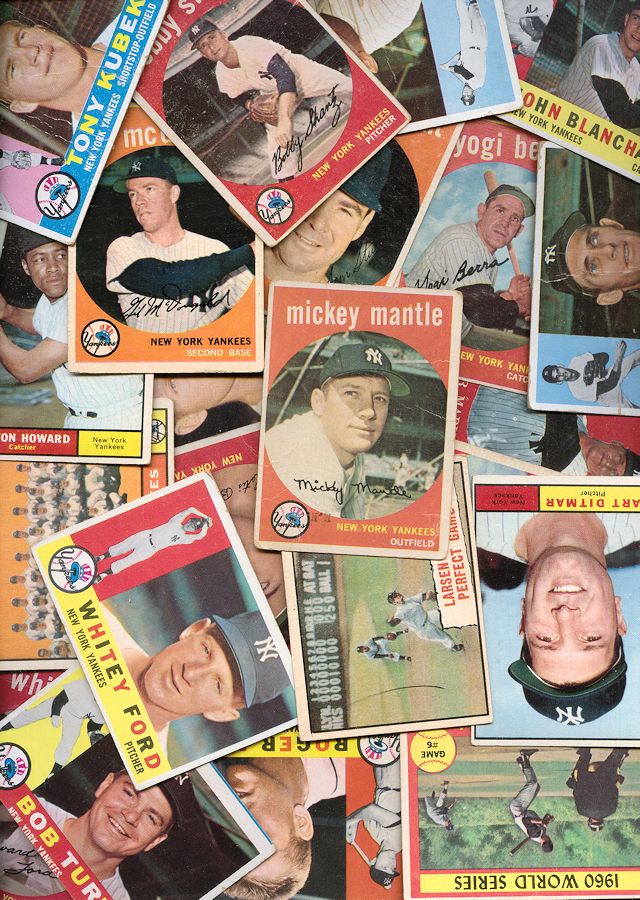

At age twelve I was keen on baseball, a big fan of the Yankees and especially Mickey Mantle.

At age twelve I was keen on baseball, a big fan of the Yankees and especially Mickey Mantle.

Miss Pool often called on us to write on the blackboard. We diagrammed sentences. We wrote sentences to demonstrate our knowledge of the subject being studied. I always managed to insert “Mickey Mantle” into whatever I wrote, whether the subject was health and nutrition (“Protein, carbohydrates, and fats help Mickey Mantle hit homers”) or social studies (“The Eskimo villagers sewed a caribou parka for their guest, Mickey Mantle”).

But Miss Pool was indulgent. She graded me on spelling and mechanics and grasp of subject matter, not level of geekiness.

Nonetheless, in that mysterious sanctum, the teachers lounge [cue diabolical laughter], where we students imagined that teachers smoked cigarettes and fricasseed first-graders, how Miss Pool and her colleagues must have rolled their eyes as they debated which renders twelve-year-old boys goofier: girls or sports.

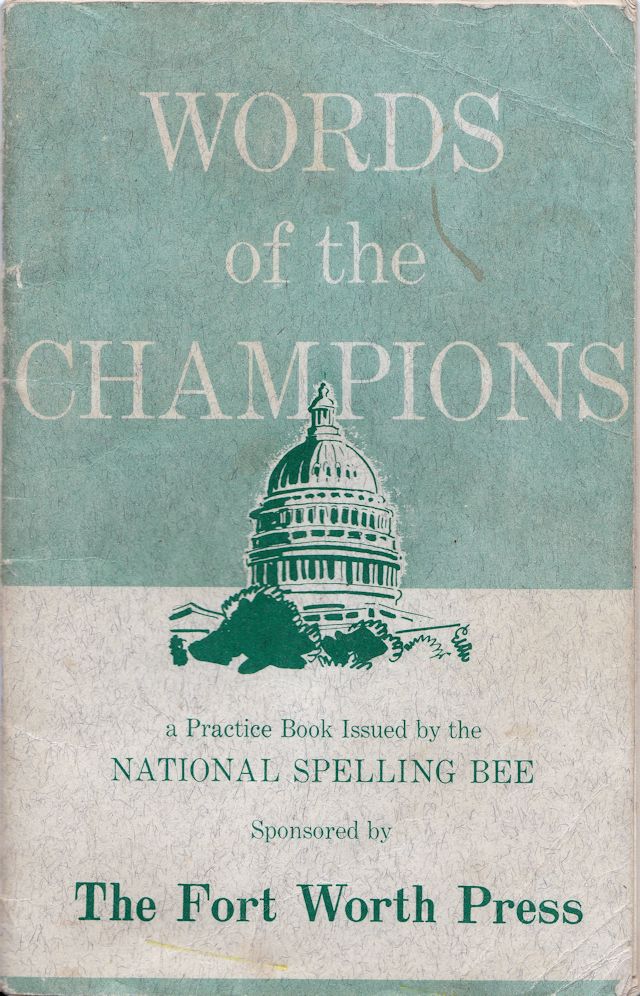

As the days passed, Miss Pool continued to be suspiciously pleasant, further rehabilitating her reputation in my eyes. She encouraged me to enter the spelling bee sponsored by the Press.

As the days passed, Miss Pool continued to be suspiciously pleasant, further rehabilitating her reputation in my eyes. She encouraged me to enter the spelling bee sponsored by the Press.

And to bring my dimes and quarters for weekly school banking at Fort Worth National Bank.

And to bring my dimes and quarters for weekly school banking at Fort Worth National Bank.

During recess she watched us students run relay races on the green—a goathead sticker-strewn field below the asphalt playground. The all-city relay race meet at Farrington Field was the Olympics of elementary school.

During recess she watched us students run relay races on the green—a goathead sticker-strewn field below the asphalt playground. The all-city relay race meet at Farrington Field was the Olympics of elementary school.

And she let us patrol boys leave class a few minutes early to attend to our school crossing duties, which we regarded as only slightly less vital to national security than the Strategic Air Command.

And she let us patrol boys leave class a few minutes early to attend to our school crossing duties, which we regarded as only slightly less vital to national security than the Strategic Air Command.

By sixth grade many of us had become voracious readers. The school system supplied us with My Weekly Reader and also let us order fiction and nonfiction books written for the juvenile market. On the days Miss Pool handed out My Weekly Reader and those special-order books, she was like a fairy queen bestowing new worlds with a wand.

By sixth grade many of us had become voracious readers. The school system supplied us with My Weekly Reader and also let us order fiction and nonfiction books written for the juvenile market. On the days Miss Pool handed out My Weekly Reader and those special-order books, she was like a fairy queen bestowing new worlds with a wand.

But in 1960 baseball was never far from my mind. When the World Series began on October 5—the Mick and the rest of the Yankees versus the Pirates—we were just four weeks into the school year. But I had already realized that Miss Pool’s vile reputation was undeserved. I realized that she must have been tarred with that reputation by students who didn’t want to “apply themselves.”

In fact, if I had been grading her, she was a solid A-minus.

By October 13 the upstart Pirates had forced the Mick et al. into game 7.

Some of us boys had the temerity to ask Miss Pool, with a tug of the forelock, if we could bring a transistor radio to class to listen to the big game. Miss Pool had been teaching thirty years. She was definitely old school. We were not hopeful.

Then she earned extra credit and the A-plus: She consented to the radio.

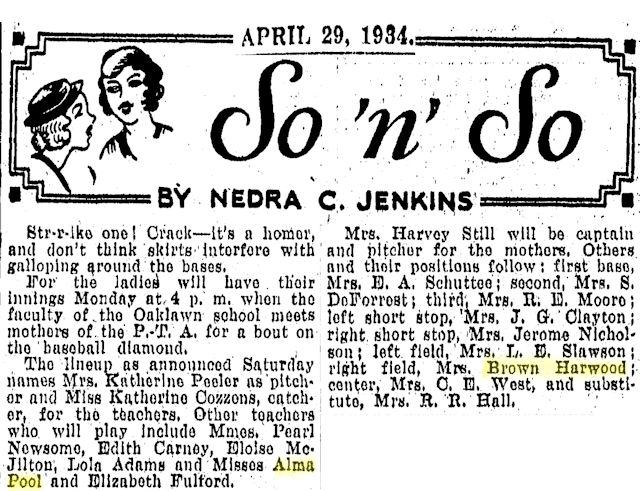

But I might not have been so surprised if I had known something else about Miss Pool: It would have sorely taxed my young mind in 1960 to imagine her playing flies and skinners or starting a 4-6-3 double play, but Miss Pool was playing baseball when the Mick was knee high to a Louisville Slugger.

But I might not have been so surprised if I had known something else about Miss Pool: It would have sorely taxed my young mind in 1960 to imagine her playing flies and skinners or starting a 4-6-3 double play, but Miss Pool was playing baseball when the Mick was knee high to a Louisville Slugger.

(On the opposing team in that 1934 Oaklawn teachers-parents game was Mrs. Brown Harwood, wife of the man who had been the no. 2 leader of the national Ku Klux Klan. The Harwoods lived nearby on Foard Street.)

Of course, Mazeroski’s walk-off home run still hangs crepe on my memories of that game 7, but when Miss Pool consented to that transistor radio, she became the first inductee in my Cooperstown of teachers.

Of course, Mazeroski’s walk-off home run still hangs crepe on my memories of that game 7, but when Miss Pool consented to that transistor radio, she became the first inductee in my Cooperstown of teachers.

Fast-forward through seven more months of classes and report cards and summer vacation to September 4, 1961. After class on my first day of seventh grade at William James Junior High School, I walked home. D. McRae Elementary School was on my way, and I walked up the worn steps to the third floor. Miss Pool was, as I had known she would be, still at her desk after classroom hours, attending to first-day details.

I wish I could tell you what we talked about that day. But I don’t remember. What I remember is the fact of my pilgrimage. Miss Pool was the first of only two teachers in sixteen years of education I went back to see after graduation.

I wish I could tell you that when I walked into her classroom on that afternoon in 1961 she looked at me over the top of her glasses, pushed them up with her middle finger, and said, as if I was still her geeky sixth-grade student, “The Mick went three for four against the Orioles today.”

She didn’t.

But that’s how I remember her.

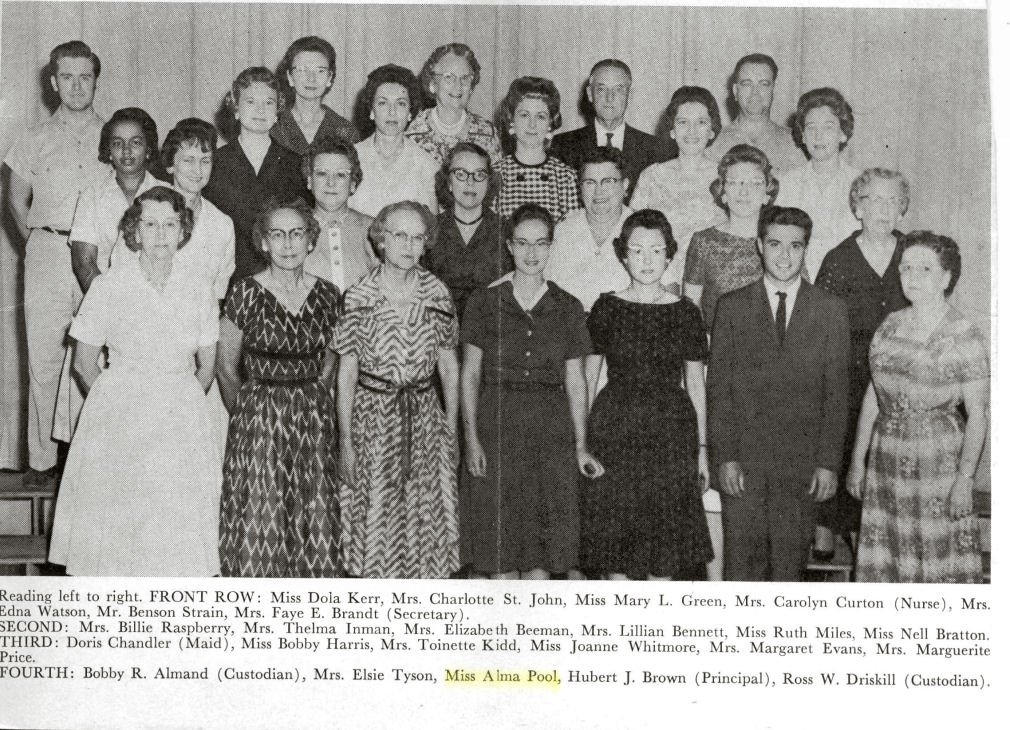

(Photo from Sherry Newman Mallory, class of 1961.)

(Photo from Sherry Newman Mallory, class of 1961.)

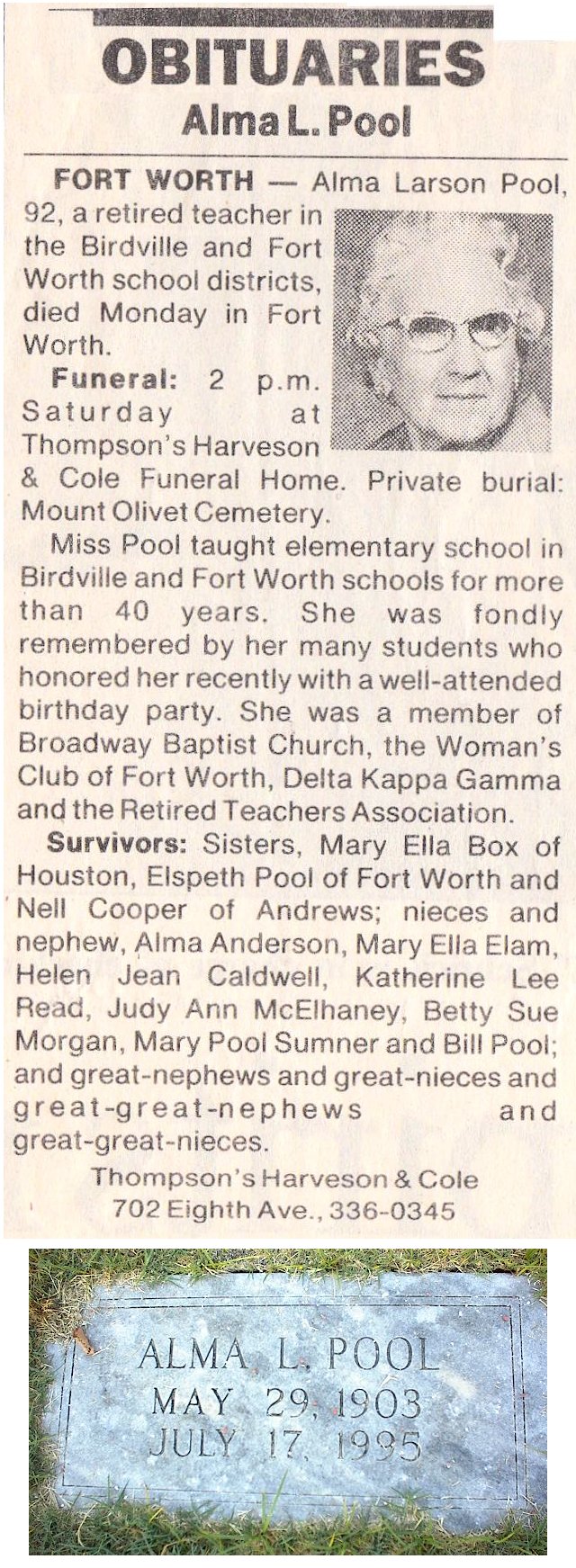

Miss Alma Larson Pool died in 1995. (Obituary from Dan Washmon, class of 1962.)

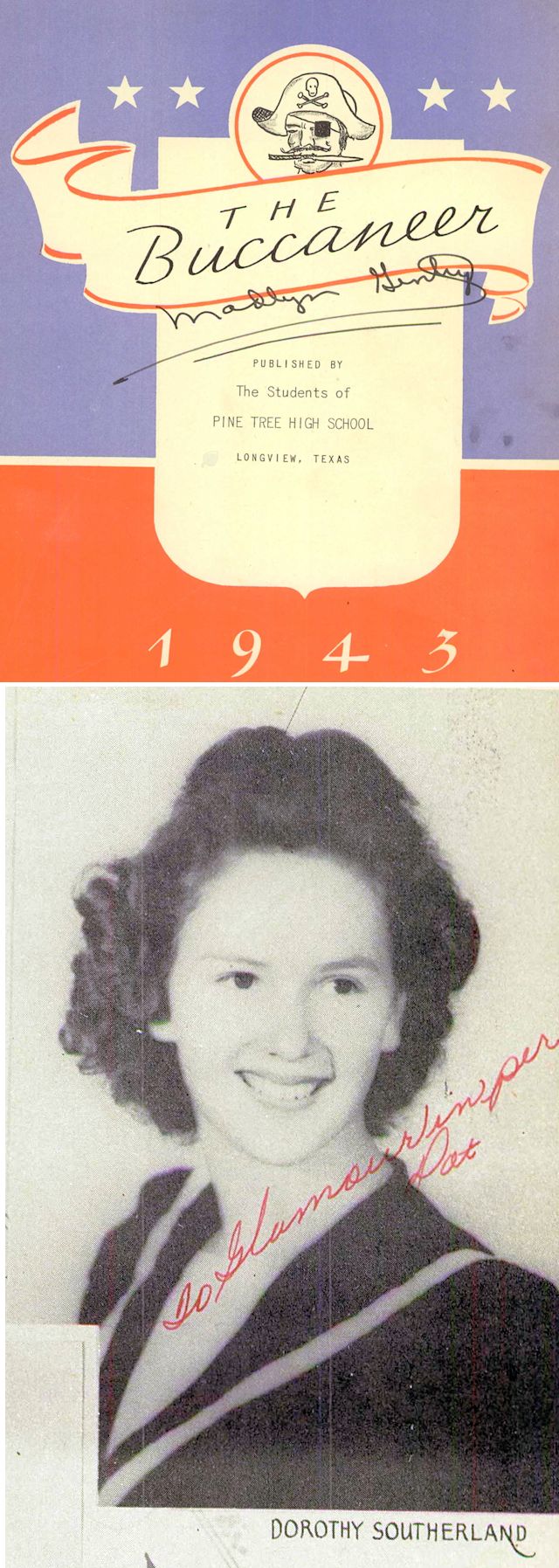

Mrs. Dorothy Southerland Estes

“Her name was Dorothy Estes, and she would change my life.”

That sentence—distilling a turning point in the life of young Phil Vinson (Poly High School class of 1958) in his memoir Ink in the Blood—would have evoked a “me, too” chorus from many of the former students of Mrs. Dorothy Estes.

Dorothy Estes was indeed a life-changer.

Of course, teachers by definition are life-changers, aren’t they? The good ones change lives by imparting knowledge. But the best ones change lives by also imparting self-confidence, ethics, standards of excellence, a sense of curiosity.

Dorothy Estes—like Alma Pool—was that kind of teacher.

Dorothy Southerland grew up in east Texas as the daughter of a Baptist minister (although she once told me, with a sly smile, “Being raised a Baptist made me a good Episcopalian”). She attended high school in Longview. In 1947 she married Emory Estes. The next year she graduated from East Texas Baptist College. Her first teaching job was at Marshall Junior High School, where Bill Moyers was her student newspaper editor.

Dorothy Southerland grew up in east Texas as the daughter of a Baptist minister (although she once told me, with a sly smile, “Being raised a Baptist made me a good Episcopalian”). She attended high school in Longview. In 1947 she married Emory Estes. The next year she graduated from East Texas Baptist College. Her first teaching job was at Marshall Junior High School, where Bill Moyers was her student newspaper editor.

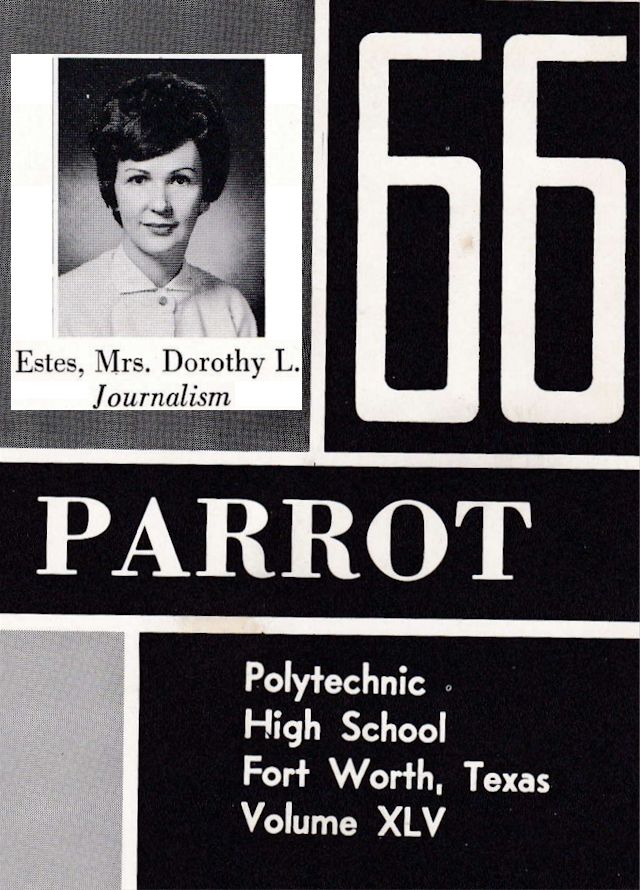

Mrs. Estes came to Poly High in 1956. She taught first English and then journalism and sponsored the yearbook and newspaper through 1966.

Mrs. Estes came to Poly High in 1956. She taught first English and then journalism and sponsored the yearbook and newspaper through 1966.

Five years after I left Miss Pool’s sixth-grade class, I was seventeen, a junior at Poly High School. I enrolled in journalism class, having to idea what it was about.

Five years after I left Miss Pool’s sixth-grade class, I was seventeen, a junior at Poly High School. I enrolled in journalism class, having to idea what it was about.

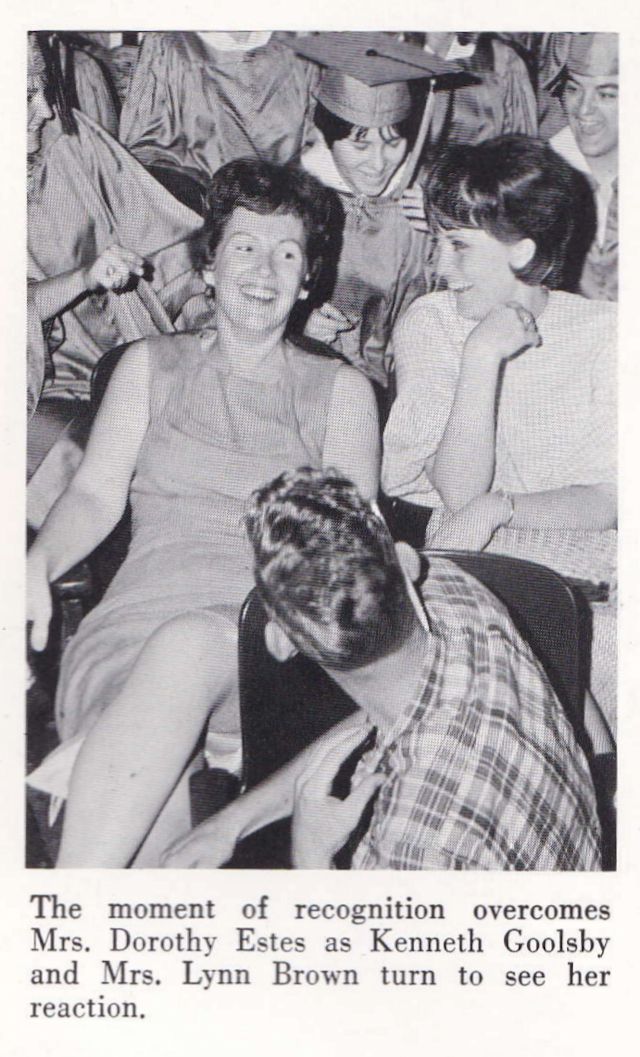

By the time I found out, the school year was ending, and Mrs. Estes announced that she was leaving Poly High to teach elsewhere my senior year.

Two of her final acts before leaving Poly High in 1966 were to appoint Cathy Hardisty and me co-editors of the Parakeet school newspaper for our senior year and to tell me to read S. I. Hayakawa’s Language in Thought and Action over the summer.

I still have that book.

Mrs. Estes later recalled of her years at Poly High: “I taught two future Fort Worth mayors, a number of doctors, lawyers, some plumbers, some good businessmen, and many other wonderful people.”

From Poly High Mrs. Estes moved on to Texas Wesleyan College, then Tarrant County Junior College for its first two years. There we were reunited, and she named me editor of a student newspaper that did not yet exist. In fact, the campus was still under construction. The newspaper staff’s office was not ready. So, we started the school newspaper in her tiny faculty office. At times her office resembled the stateroom in A Night at the Opera).

From TCC she moved to the University of Texas at Arlington, where she was director of student publications from 1970 until her retirement in 1996.

Mrs. Estes and her husband Emory combined for a century of teaching. Emory retired as chairman of the English Department at UTA after more than fifty years on the faculty. Husband and wife—soulmates on the inside—were a study in contrasts on the outside. Emory was as looming and theatrical as Mrs. Estes was petite and low key. Emory blocked out the sun and thundered to his students with the voice of God; Dorothy stood in stockinged feet and spoke so softly that you leaned forward to hear.

Mrs. Estes and her husband Emory combined for a century of teaching. Emory retired as chairman of the English Department at UTA after more than fifty years on the faculty. Husband and wife—soulmates on the inside—were a study in contrasts on the outside. Emory was as looming and theatrical as Mrs. Estes was petite and low key. Emory blocked out the sun and thundered to his students with the voice of God; Dorothy stood in stockinged feet and spoke so softly that you leaned forward to hear.

Unflappable, tactful, and patient, she was the consummate persuader with her—to use Twain’s words—“softy soothering ways.”

Unflappable, tactful, and patient, she was the consummate persuader with her—to use Twain’s words—“softy soothering ways.”

She had a knack for persuading us students to do what was best (even when we didn’t want to), whether it was to make our student newspaper story better or to make our grade better or even to make our life better. Most of the time we would go along with her appeal to what Lincoln called “the better angels of our nature,” unaware until later that we had been “Dorothyed.”

Mrs. Estes’s philosophy was, “I function more like a coach than a teacher, but I do not call the plays. The students provide the vision, the energy, and the courage; I am responsible for the coffee, the criticism, and the comfort. They find events, trends, issues; I offer perspective.”

And she was protective of her students when, as crusading, investigating young journalists, they took on the powers-that-be of the campus or the community.

Mrs. Estes was to her students a mother, a confessor, a career counselor, a cheerleader, a loan officer, an Ann Landers.

As a teacher in high school and college, she taught students between the ages of sixteen and twenty-one. An awkward age.

But she overlooked our follies of youth, tolerated our mood swings between silly and sullen, and knew how to treat an ego as if it were an eggshell. She cooed her support as we coped with peer pressure, pimples, and all-consuming crushes.

Dorothy Estes was the teen whisperer.

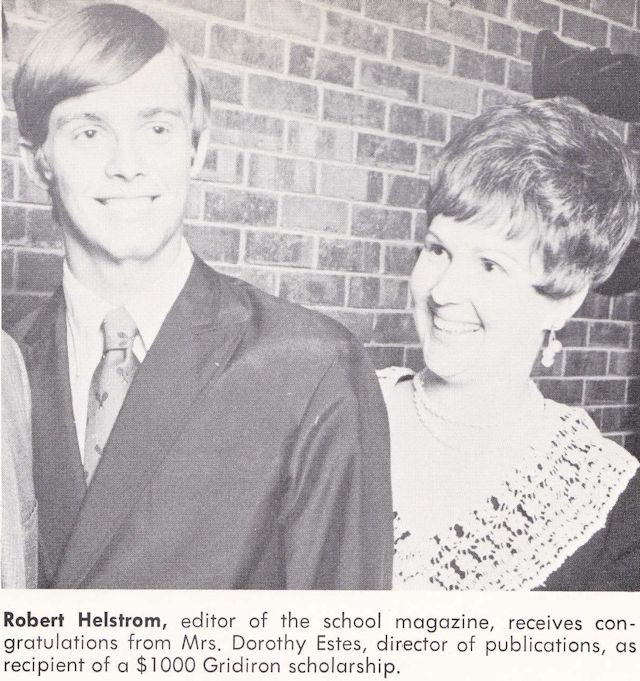

She helped us find jobs, win scholarships. She lent students money to buy lunch or to keep an old jalopy running until payday.

She helped us find jobs, win scholarships. She lent students money to buy lunch or to keep an old jalopy running until payday.

She helped all of her spiritual children. Night or day.

The heart of Dorothy Estes did not keep office hours.

She had one more remarkable quality: a memory like a tape recorder. Although during her career she taught thousands of students, she seemed to remember them all. And not just names and faces but also details: something you said in 1958, something you did in 1969, the lead paragraph of the story for which you won an award thirty years earlier, the name of “that pretty little girl you were seeing” forty, fifty years earlier.

I often wished her memory weren’t so good.

Mrs. Estes measured her own success by the success of her students, but her success was recognized by her peers. In 1995 Mrs. Estes received the Freedom of Information Award of the Society of Professional Journalists. The next year she received a commendation for outstanding service to academic journalism from the Texas Senate. In 2003 the Texas Intercollegiate Press Association inducted her into its Hall of Fame (along with Bill Moyers and Walter Cronkite).

Former students such as myself continued to reunite with Mrs. Estes for decades after we graduated.

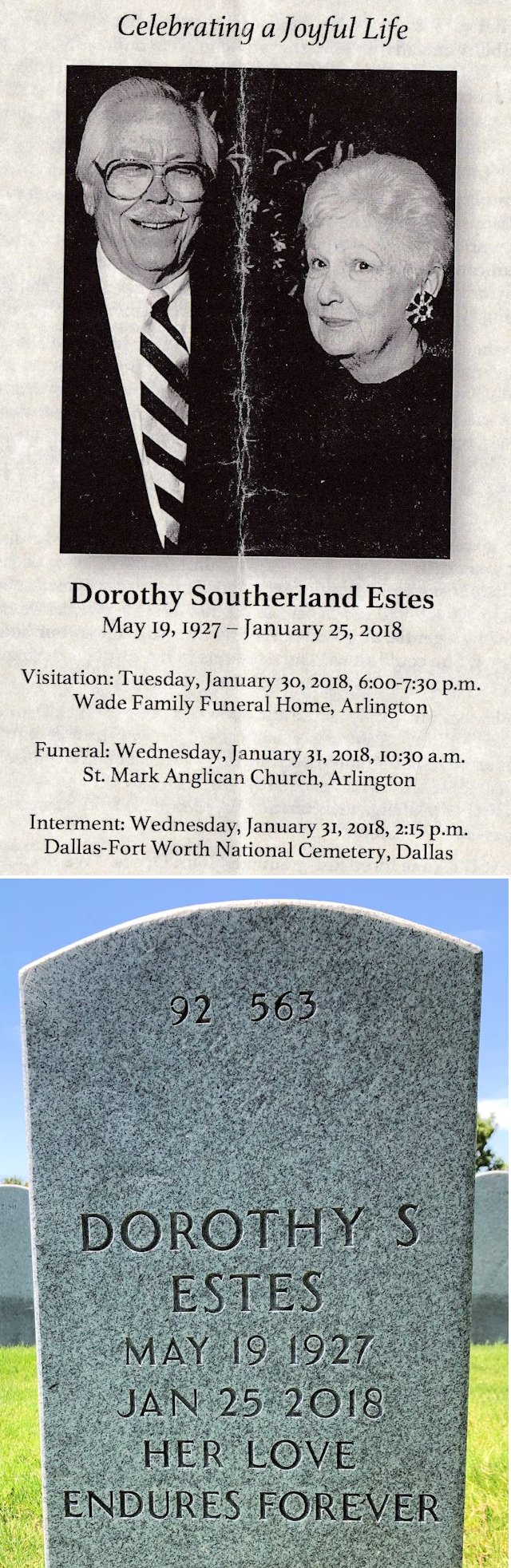

Emory was the first to go. He died in 2013. At his funeral she sat beside him as we filed by the casket. She smiled when she saw me.

“You wore a suit. You know you’ll have to wear that suit one more time.”

In 2017 she had dinner with a group of friends and a few of us former students from the 1950s and 1960s. At eighty-nine she had become physically frail but remained mentally sharp.

It was the last time we saw her.

In 2018 I had to “wear that suit one more time.” She died on January 25 at age ninety.

John H. Ostdick, editor of UTA’s Shorthorn student newspaper in 1979, recalled: “Dorothy was incredibly astute and aware. Among her many strengths was the ability to look inside of people, to inspire them to become their best. Her light cannot be vanquished, as it lives on in so many, whether they became working journalists or probing, well-functioning communicators in whatever field they pursued.”

Indeed, according to her obituary in the Star-Telegram, she placed “more than 600 students in the communications workforce.” Her students went on to careers as editors, writers, and photographers all over the country.

Upon learning of her death, Bill Moyers posted on Facebook: “She was such a good [but tough] soul. She was kind to others but always stood by her own ideas and values. So many years have passed that I can’t speak with certainty about how she did it, but I remember my curiosity about the world expanding during my time in her class.”

Moyers, like Phil Vinson, spoke for many of her former students.

To read the tributes to her in obituaries in the Star-Telegram and Morning News and on the Facebook page “Remembering Dorothy Estes” and to eavesdrop on conversations at her funeral, you’d swear that people were talking about their own mother.

And in a way they were.

Mrs. Estes’s funeral was attended by her two biological children (Sharon and Emory III) and by dozens of her spiritual children: students who across five decades sat in her classrooms and staffed the yearbooks and student newspapers that she supervised.

At her funeral her former students—the spiritual children of Dorothy Estes—celebrated of the life of a life-changer.

At her funeral her former students—the spiritual children of Dorothy Estes—celebrated of the life of a life-changer.

And all of us—many of us old enough to be great-grandparents—felt orphaned by her passing.

Posts About Education in Fort Worth

Posts About Women in Fort Worth History