If the following crime story were a work of fiction, it might be entitled Sherlock Holmes Meets the Big Lebowski.

It has elements of both works of fiction: the communication via cryptic messages in the “personal” column of newspaper classified ads (The Bruce-Partington Plans, The Sign of Four, The Red Circle) and the threatening letters (The Five Orange Pips, The Adventure of the Dancing Men) of the Sherlock Holmes stories and the rolling handoff of a satchel of money to an extortionist (voice on mobile phone to Walter Sobchak: “You are approaching a wooden bridge. When you cross it you throw the bag from the left window of the moving car. Do not slow down. We watch you.”) of The Big Lebowski.

The year was 1936. America was still suffering through the Great Depression, although west Texas was somewhat buffered by the oil boom that had begun at Ranger in 1917.

Still, in small towns such as Eastland and Cisco, although there were plenty of Haves, there remained far more Have-Nots.

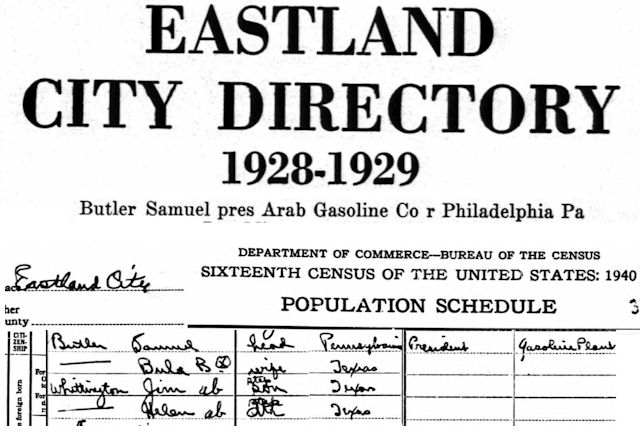

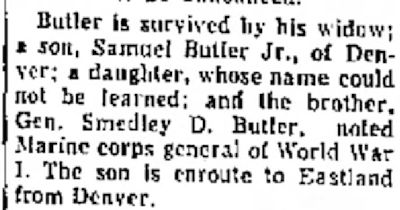

One of the Haves was Samuel Butler, president of Arab Oil Company in Eastland. Butler was from a prominent Quaker family of Pennsylvania. His father had been a Pennsylvania congressman.

One of the Haves was Samuel Butler, president of Arab Oil Company in Eastland. Butler was from a prominent Quaker family of Pennsylvania. His father had been a Pennsylvania congressman.

His brother was Marine Major General Smedley Butler, who at the time of his death was the most decorated Marine in history.

His brother was Marine Major General Smedley Butler, who at the time of his death was the most decorated Marine in history.

In Eastland, Samuel Butler was a big fish in a small pond, and people in the area knew the basic facts about him:

- He had money.

- He had children (Samuel Jr., eighteen, and Helen, sixteen).

One Have-Not was determined to make fact 1 and fact 2 add up to 3,000.

On July 24 Samuel Butler received a letter, mailed in Eastland on July 23:

“We have decided you are able to pay three thousand $3,000 for protection of your children if this taken to police or you do not follow instructions we will rub out one. Then raise the amount to twenty five thousand on the other. Also we give protection for the next seven years on kidnaping and business like this which we know and can protect you from better than the police don’t try any funny business for we need one killing to terrorize others. And don’t think we wont do it for we will. Then demand said price above on the other one. Have the money 1,500 in fives and 1,500 in tens all this money must be in old bills. Take the money to Fort Worth check in the Texas Hotel under the same name that is on the envelop this is mail in. Then insert this add in the personal of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram (John Ring we are ready sign S. B.) (July 26) (Sunday) paper and Monday July 27, 1936 but not later. From there we will give you instructions on how to deliver the money. Last warning dont try any funny business or you will be sorry the rest of your life remember the life of your children cannot be brought back. OUR SIGN FFFF.”

It was a letter that would make any parent blanch and any English teacher cringe.

Butler’s mother had died at his home in June. Perhaps the letter writer, FFFF, knew this and was preying on Butler’s grief.

Butler consulted with law enforcement officials, including the FBI, on how to respond. At the time, Butler’s two children were at home during the summer school recess. For their safety he sent them to stay with relatives in Philadelphia.

Should he pay the $3,000 ($55,000 today)? FFFF had instructed Butler to take the money to the Hotel Texas, but the delivery was not to be made there. Why? Did FFFF want Butler to go to the hotel in Fort Worth just to see if Butler would follow orders? FFFF spoke of “we.” Was that a bluff, or did he really have confederates? Could Butler and the FBI catch the extortionist in a trap of his own greed?

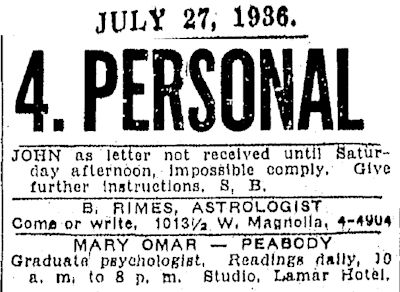

FFFF had instructed Butler to place this message in the “personal” column of the Star-Telegram classified ads on July 27: “John Ring we are ready sign S. B.”

Instead Butler placed this message, claiming that he had not received FFFF’s letter in time to place a message on July 26:

Perhaps Butler was telling the truth. Perhaps Butler had not yet decided to meet FFFF’s demands. Perhaps Butler was calling FFFF’s bluff. Perhaps Butler and lawmen needed more time to work out a strategy.

Perhaps Butler was telling the truth. Perhaps Butler had not yet decided to meet FFFF’s demands. Perhaps Butler was calling FFFF’s bluff. Perhaps Butler and lawmen needed more time to work out a strategy.

On July 28 Butler received a second letter, mailed special delivery from Fort Worth on July 27:

“We are not playing Sam and know you have had time to call in a postal inspt. Take warning leave all laws out of this. Don’t mark or take serial no. of bill. You have had time to have everything ready so have money in brief case come to Fort Worth July 29 buy a ticket to Amarillo, Texas, on the Fort Worth and Denver RR. Take night train 10:45 p.m. ride back platform or observation platform if they have one. Somewhere between Fort Worth and Amarillo a man will step out between the rails just after train passes and with a light make the letter F. When the light is first turn on it will be up over head making a down stroke then turn out until up over head again then on to make first horz. [horizontal] stroke then off and back on for second horz. stroke. Drop money between rails. Remember no law on earth can bring back life. Soon or later we can get any one if they try to put the xx [double cross] on us so leave the law out and pay off. We will do as we said before. If after the pay off you want to get touch with place add in personal to John Ring. SIGN FFFF.”

FFFF had instructed Butler to take a Fort Worth & Denver train from Fort Worth to Amarillo on July 29 and to station himself at the rear of the rear coach. Somewhere along the way a man near the tracks would signal to Butler by forming the letter F with a light as the train passed. Butler was to toss the money in a briefcase from the coach.

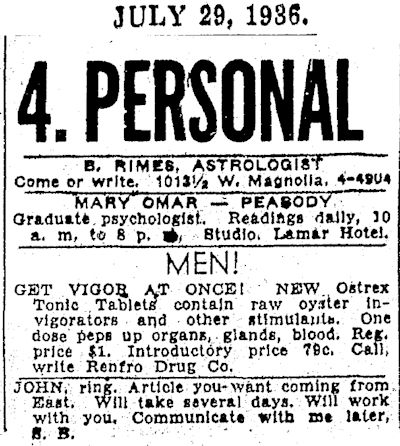

Butler again did not do as ordered. Instead he placed this message in the “personal” column of the Star-Telegram classified ads on July 29:

Was Butler stalling for time? Was he trying to provoke FFFF? If so, it worked. On August 5 Butler received a third letter, mailed on August 4, again from Fort Worth:

Was Butler stalling for time? Was he trying to provoke FFFF? If so, it worked. On August 5 Butler received a third letter, mailed on August 4, again from Fort Worth:

“We have not forgot you. We have been busy with others who have cooperated with us and have not tried to give us the double cross as you seem to have done. We are giving you one more chance and if you fail to carry out instructions we will do as we said before. You can’t hide your children where we can’t find them sooner or later. If the coppers should catch one of my men we will take the life of both your kids and leave you to think how easy it would have been to have let them keep living. After all $3,000 is a small amount in comparison with the life of one and may be both. This is your last chance take it or leave it but if we do not receive the money this time we will do as said in first notice then the next time we run into some one who don’t think their childrens life is worth $3,000 (when they have plenty of money) or that we can’t get to them will think twice before they give us any trouble. This time (Thursday night Aug. 6) take T. P. train to El Paso. Ride back platform do not leave it for any reason until money is delivered for any mistake on your part you will regret the rest of your life. This time we will leave out the light instead someone will call these words (Sam Butler drop that money) have money as we instructed before. Remember Thursday night train leaves somewhere around midnight. If you think you can out smart us just fail to deliver money and we will see. You might catch the man who does the killing but we don’t think so. Even if you did that would not bring back the life of your child. Think it over which is worth the most your child or $3,000? Remember Eastland to El Paso T. P. train. Thursday night Aug. 6, 1936. Train leaves around midnight. These are the words, Sam Butler drop that money. FFFF

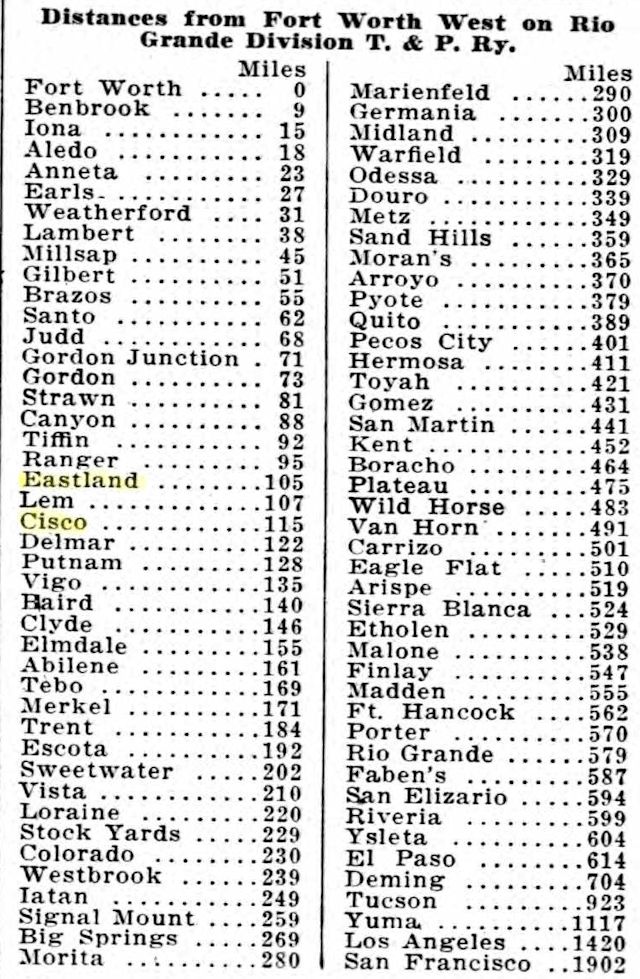

FFFF warned Butler about trying to “double cross” him and repeated his death threat to Butler’s children. FFFF also changed the plan for the delivery of the extortion money: Butler was to take a Texas & Pacific night train from Eastland west toward El Paso, again stationing himself at the rear of the rear coach with the money. Butler was to listen for someone on the tracks to call out, “Sam Butler, drop that money.”

The Texas & Pacific passenger train from Fort Worth west to San Francisco made a lot of stops in Texas, including at Eastland and Cisco, just ten miles apart—with a stop in between at Lem! The train barely left Lem before it had to begin slowing down to stop in Cisco.

The Texas & Pacific passenger train from Fort Worth west to San Francisco made a lot of stops in Texas, including at Eastland and Cisco, just ten miles apart—with a stop in between at Lem! The train barely left Lem before it had to begin slowing down to stop in Cisco.

And FFFF knew that.

With Butler on the train after midnight on April 7 were two railroad agents and one FBI agent

Police in a car shadowed the train on a road that roughly paralleled the railroad track.

Just minutes after leaving Lem the train slowed as it entered Cisco. The rear car was far enough from the engine, and the train was going slowly enough that Butler could hear someone call out, “Sam Butler, drop that money” despite the clacking of the wheels as they passed over the rail joints.

In the dark before dawn on August 7, two blocks before the depot Butler heard the signal: “Sam Butler, drop that money.”

Butler tossed the satchel out the rear of the coach onto the tracks.

And the FBI agent tossed a flare out the rear of the coach, illuminating a man on the tracks.

The man ran from the light.

The three agents on the train and the police officers in the chase automobile pursued the man, but he soon ran beyond the illumination of the flare and disappeared in the darkness.

He escaped but without the satchel.

No great loss: Newspapers would later report that just as in The Big Lebowski, the satchel did not contain the extortion payoff.

As the search for FFFF continued after sunrise August 7, Cisco Police Chief Milton Perdue theorized that the extortionist was “someone from Eastland who knew Butler pretty well.”

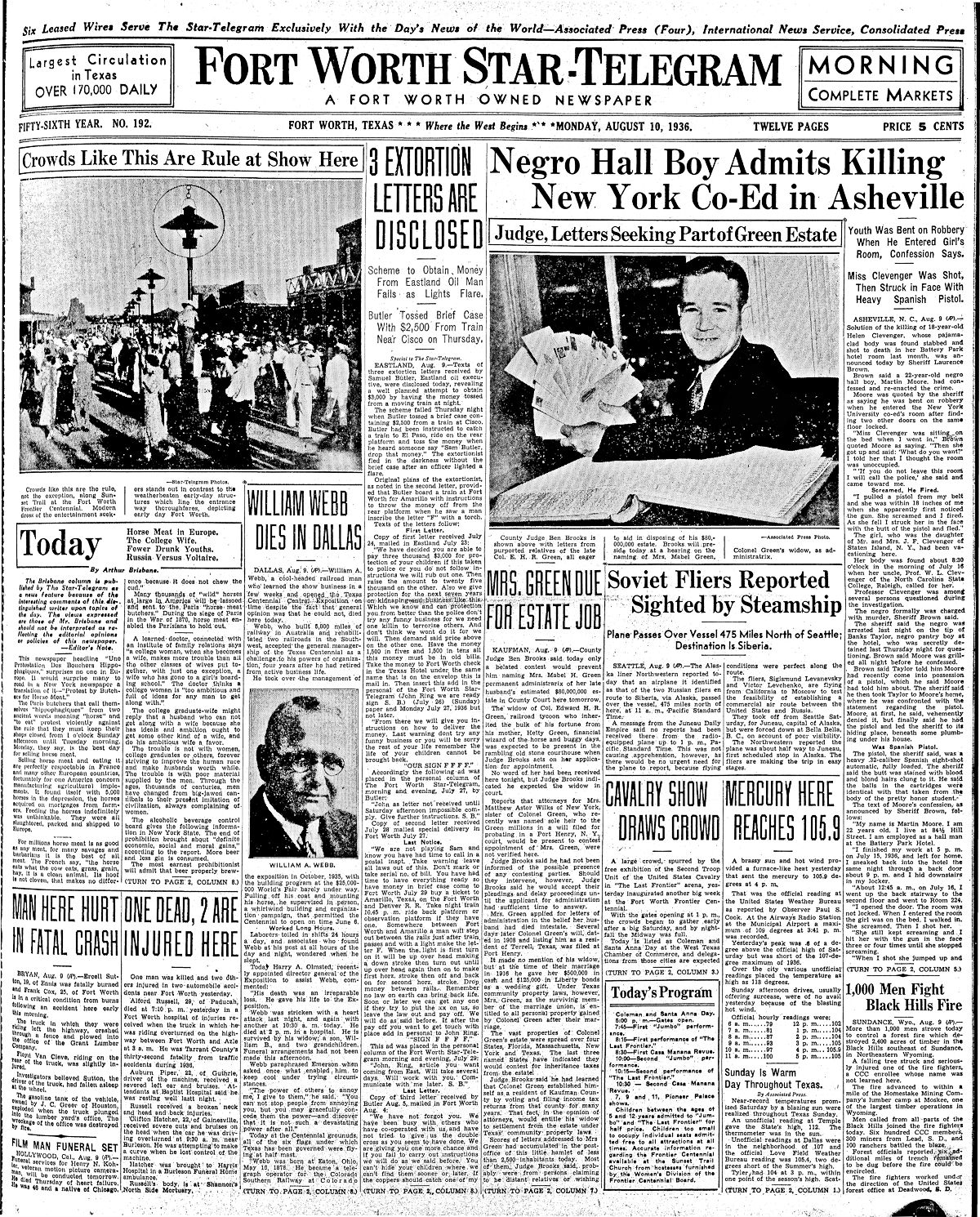

Only after the money handoff failed did newspapers report the chronology of the extortion attempt.

Only after the money handoff failed did newspapers report the chronology of the extortion attempt.

Note that Fort Worth’s Frontier Centennial was under way.

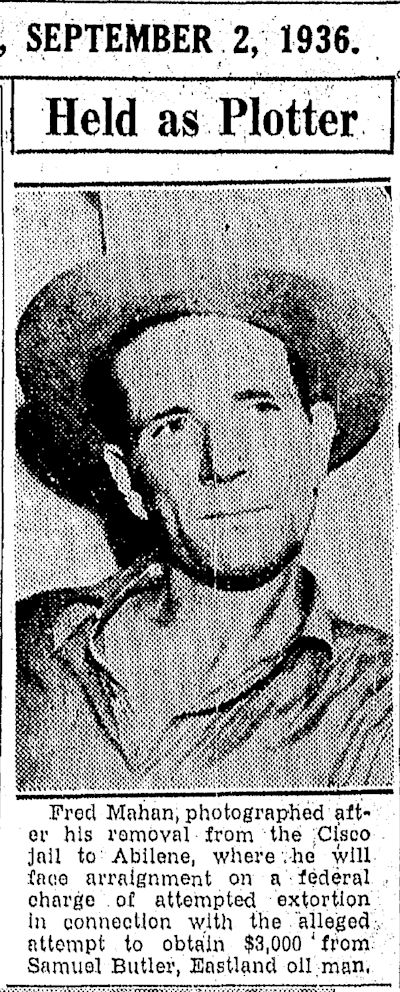

On August 17 Chief Perdue arrested Frederick E. Mahan, thirty-eight, on a Cisco street.

Mahan had become a suspect after a Katy railroad agent told police that a train crew had brought to him a man who needed medical treatment for lacerations. The man refused treatment. The agent recalled hearing that the extortionist had run into a barbed wire fence in his flight from police.

Butler and the FBI agent identified Mahan as the man who had called out “Sam Butler, drop that money.”

Mahan’s fingerprints matched those on the three extortion letters mailed to Butler.

Mahan was held in secret detention in Cisco until he was taken to Abilene to be arraigned.

Mahan was held in secret detention in Cisco until he was taken to Abilene to be arraigned.

Mahan was charged by the FBI with attempted extortion. Mahan proclaimed his innocence, said he was a “victim of circumstances.”

Mahan was charged by the FBI with attempted extortion. Mahan proclaimed his innocence, said he was a “victim of circumstances.”

Chief Perdue said Mahan had lived in Cisco about five years. Mahan described himself as a laborer.

Chief Perdue said Mahan had lived in Cisco about five years. Mahan described himself as a laborer.

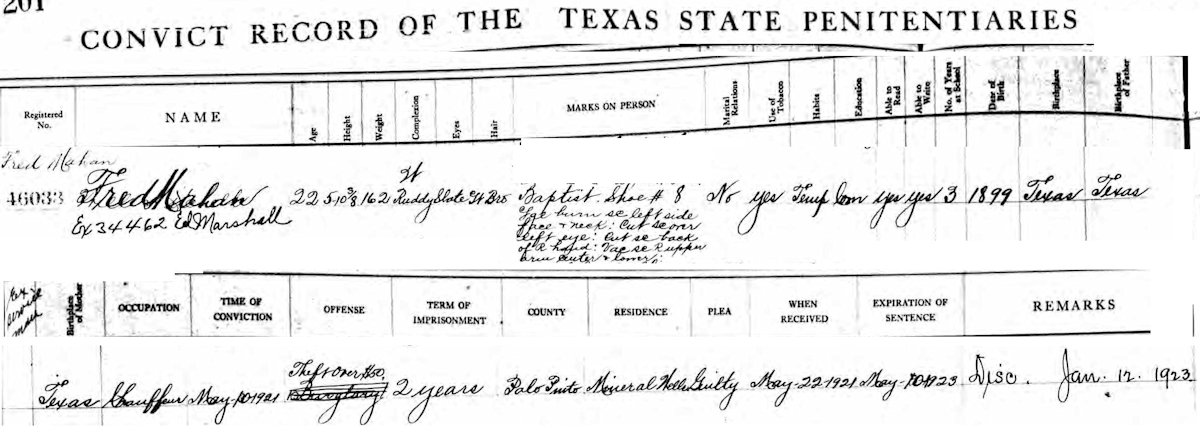

He had served two years in prison for theft.

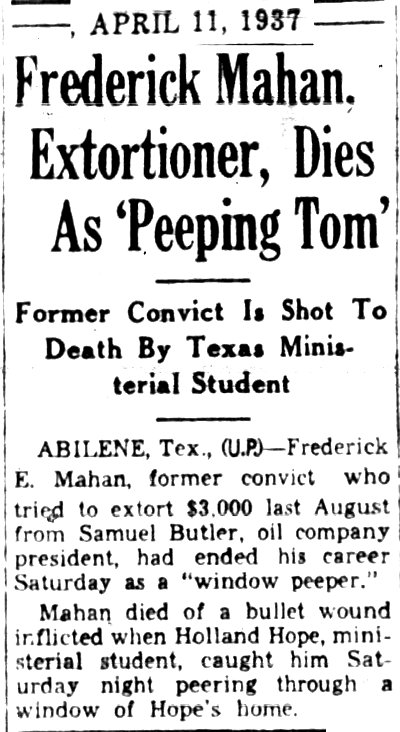

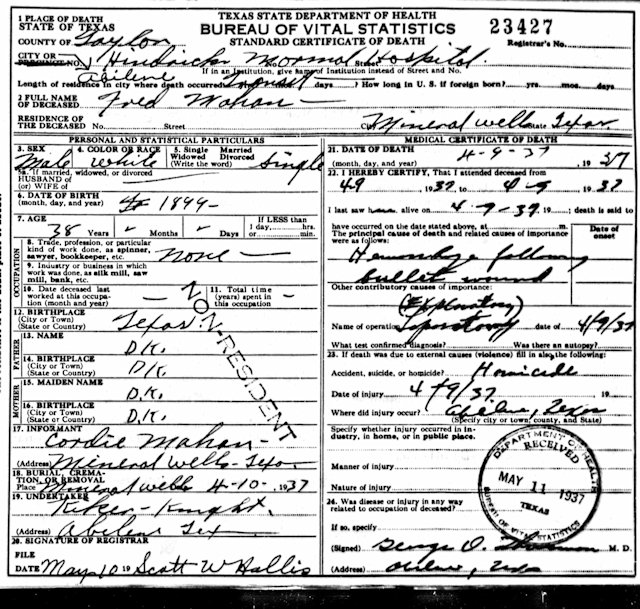

In April 1937 Fred Mahan was free on bond in Abilene, awaiting trial for attempted extortion.

Meanwhile Holland Hope, theological student at Abilene’s McMurry University, had seen footprints in a flowerbed beneath a window of his home three days in a row.

Suspecting a window peeper, on the night of April 9 Hope hid in his back yard and monitored the windows.

About 9 p.m. a man entered the back yard from the alley, walked past Hope, and peered in a window.

“You’re just the man I’m watching for!” Hope shouted.

Just as Fred Mahan had run when the flare was tossed from the railroad coach, again he ran.

This time he didn’t escape.

Hope ordered the peeper to halt, but he kept running. Hope fired one shot from a .41-caliber pistol.

Fred Mahan was killed.

Fred Mahan was killed.

He previously had served a jail sentence in Oklahoma City for window peeping.

Police said no charges would be filed in the shooting.

Fast-forward to 1947. Samuel Butler was killed by a business associate who then committed suicide.

Fast-forward to 1947. Samuel Butler was killed by a business associate who then committed suicide.

Still alive and well to mourn Butler were his two now-grown children whom Fred Mahan had threatened to “rub out” in 1936.

Still alive and well to mourn Butler were his two now-grown children whom Fred Mahan had threatened to “rub out” in 1936.

Let us give Sam Elliott’s “Stranger” in The Big Lebowski the last word:

“Well, that about does ’er, wraps ’er all up.”