A roulette wheel, some poker chips, a prostitute’s Neiman Marcus cape. Most people would regard these items as the trappings of vice. But other people, in another light, regard these items as the spoils of war—a war in which “good” prevailed over “evil.”

The war would last twenty years.

The battlefield: forty-six oak-shaded acres on a hilltop in west Arlington.

The stronghold to be stormed: Top o’ Hill Terrace gambling casino.

General leading the forces of “evil”: Fred Browning.

General leading the forces of “good”: J. Frank Norris.

And yet it all began so peacefully, even genteelly. In 1921 Dallas home economist Beulah Adams Marshall bought land west of Arlington along the Bankhead Highway (Division Street today). On a hilltop with a grand view to the west she built an elegant building of timber and sandstone and opened a teahouse, hosting teas and dinners for ladies of refinement of Dallas and Fort Worth. Women were beginning to drive more in the early 1920s, and the Bankhead Highway connected the teahouse to both cities.

And yet it all began so peacefully, even genteelly. In 1921 Dallas home economist Beulah Adams Marshall bought land west of Arlington along the Bankhead Highway (Division Street today). On a hilltop with a grand view to the west she built an elegant building of timber and sandstone and opened a teahouse, hosting teas and dinners for ladies of refinement of Dallas and Fort Worth. Women were beginning to drive more in the early 1920s, and the Bankhead Highway connected the teahouse to both cities.

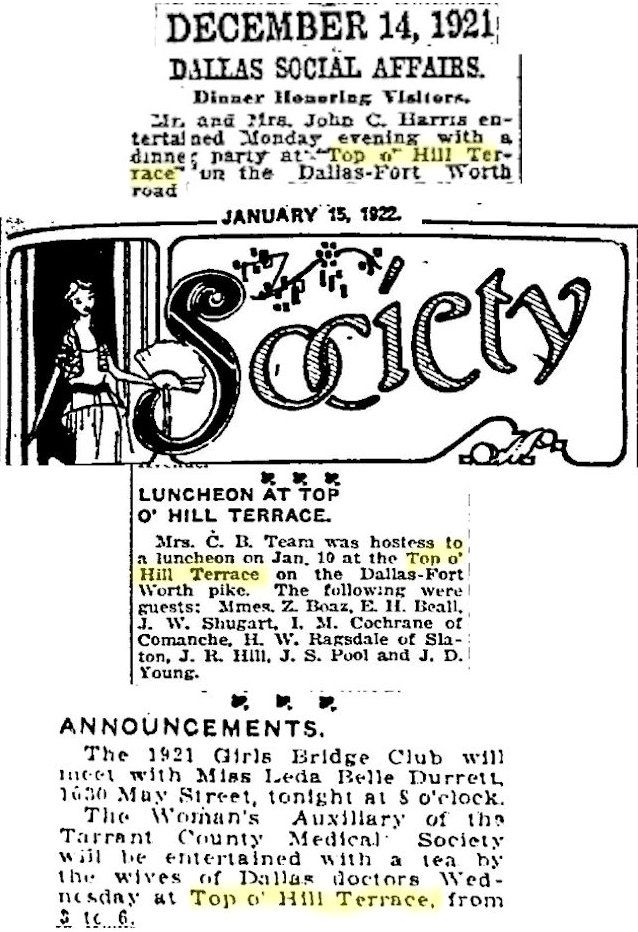

The Top o’ Hill Terrace teahouse often appeared in the society columns of both cities.

The Top o’ Hill Terrace teahouse often appeared in the society columns of both cities.

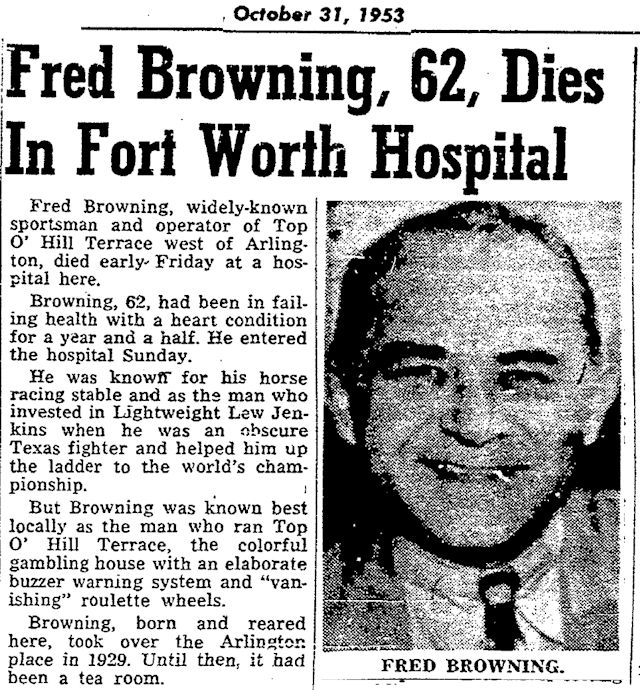

Onto the battlefield in 1930 stepped Fred C. Browning. Browning, a former plumber, was a local boy, had attended the Fifth Ward School on Fort Worth’s near East Side.

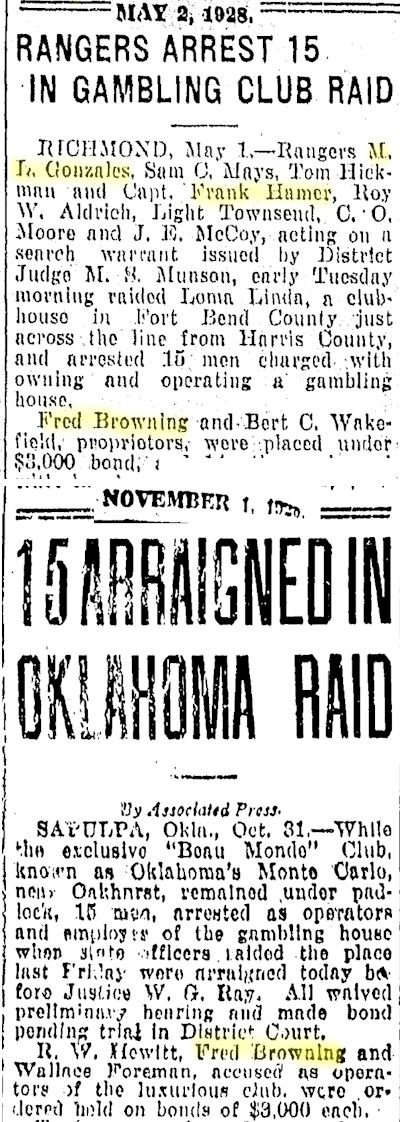

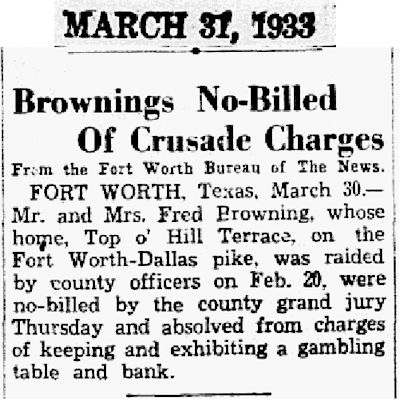

Browning knew his way around a casino, had lots of contacts both inside and outside the law. Browning and wife Mary purchased Top o’ Hill Terrace teahouse and forty-six acres around it as part of an audacious plan: The Brownings would convert the teahouse into a gambling casino. (In the top clip “M. L. Gonzales” was Manuel T. “Lone Wolf” Gonzaullas. He and Browning would meet again. Also note Frank Hamer of Bonnie and Clyde fame.)

The acreage that the Brownings bought was well suited to their plan. It was beyond the city limits—and city law enforcement. It was centrally located on a major highway between Fort Worth and Dallas. It was secluded. It was parklike. The property had only one way in. The teahouse could not be seen from the highway.

But the teahouse itself was lacking. So Browning moved the teahouse off its foundation temporarily so that a two-tiered basement could be dug. In the paneled-and-upholstered basement Browning built a fifty-by-sixty-foot gaming room and a twelve-foot curved bar with a wall of mirrors behind it.

The teahouse was moved back over the basement. The teahouse over the basement casino housed a nightclub and the Brownings’ living quarters.

Browning also built a tiled swimming pool.

Oh, and a brothel.

Fred Browning was a gambler’s gambler. Browning knew that oilman W. T. Waggoner, who had built his Arlington Downs racetrack five miles east of the teahouse in 1929, was lobbying the state legislature to allow parimutuel gambling. If betting on horses became legal, the track would draw lots of gamblers to Arlington.

Browning intended to give those gamblers an alternative to the track. In converting a teahouse into a casino he was gambling on the state legislature making parimutuel gambling legal.

It did.

It did.

In addition to the casino, Browning owned a string of Thoroughbred racehorses. In fact, Browning had purchased his prized stud, Royal Ford, from Waggoner for $110,000. Browning built two stables at the Terrace, one of them just for Royal Ford.

In addition to the casino, Browning owned a string of Thoroughbred racehorses. In fact, Browning had purchased his prized stud, Royal Ford, from Waggoner for $110,000. Browning built two stables at the Terrace, one of them just for Royal Ford.

Browning even “owned” a boxer. Lightweight Lew Jenkins trained at the Terrace and won the world lightweight title in 1940. Boxer Max Baer, father of Max “Jethro Bodine” Baer Jr., also trained at the Terrace.

Browning even “owned” a boxer. Lightweight Lew Jenkins trained at the Terrace and won the world lightweight title in 1940. Boxer Max Baer, father of Max “Jethro Bodine” Baer Jr., also trained at the Terrace.

The grounds of the Terrace were worthy of a country estate, landscaped and maintained by a caretaker with a staff of four. There were fountains, stone-lined ponds stocked with fish and swans, stone footbridges, stone walls, canopied breezeways. The original tea garden had been retained.

A greenhouse kept fresh flowers on the tables in the restaurant.

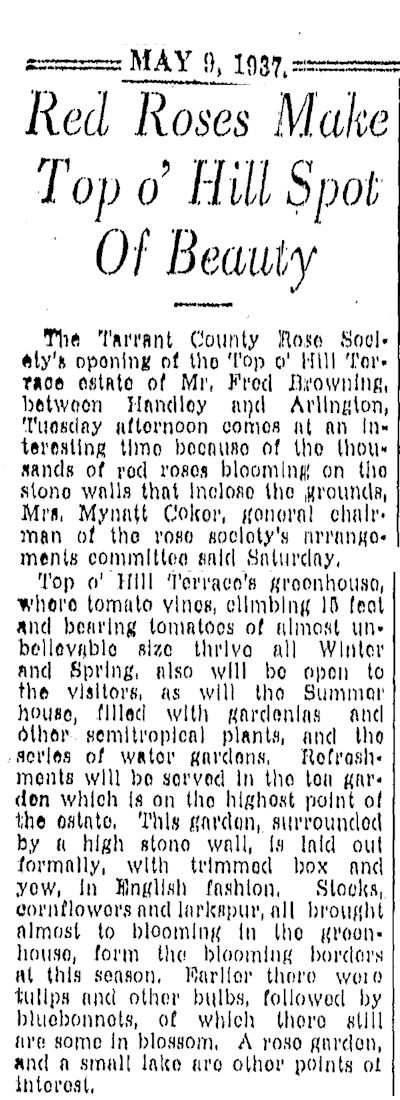

In 1937 the Tarrant County Rose Society hosted tours of the Terrace’s roses, greenhouse, and summer house.

In 1937 the Tarrant County Rose Society hosted tours of the Terrace’s roses, greenhouse, and summer house.

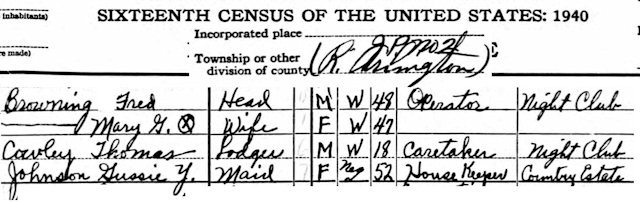

Some people who visited the Terrace were not aware that it included an illegal gambling casino and a brothel. The Terrace’s tea garden and nightclub were legitimate businesses. Browning listed himself as nightclub operator in the 1940 census.

Some people who visited the Terrace were not aware that it included an illegal gambling casino and a brothel. The Terrace’s tea garden and nightclub were legitimate businesses. Browning listed himself as nightclub operator in the 1940 census.

Along with Pappy Kirkwood’s Four Deuces club on the Jacksboro Highway, the Terrace became the place to gamble in the 1930s and 1940s before Las Vegas bloomed in the desert: Joe Louis, Dean Martin, Sally Rand, Jack Ruby, Hedy Lamarr, John Wayne, Howard Hughes, Buster Keaton, W. C. Fields, Lana Turner, Will Rogers, Frank Sinatra, Bugsy Siegel, Bonnie and Clyde (Browning asked Bonnie and Clyde to leave their guns in their car) rubbed shoulders and dice with local high-rollers: Sid Richardson, Clint Murchison. Also available were roulette, billiards, blackjack, and slot machines.

Wealthy gamblers flew in on private airplanes accompanied by bodyguards. Those who arrived by train were met at the station by a Terrace employee.

Jack Poe, who worked at the Terrace for five years as a teenager in the 1930s, recalled that a half-million dollars might change hands on a weekend during racing season.

On a weekend the parking lot was a showcase of luxury automobiles: Cadillacs, Pierce-Arrows, Cords.

Sometimes the casino didn’t close until sunrise.

Patrons were served fine food in the restaurant and, during Prohibition, bootleg liquor in the bar.

Entertainment included nude dancing girls, performances by Tommy Dorsey’s band, Ruth Laird’s Texas Rockets ballerina troupe, and local performers Ginger Rogers and Mary “Punkins” Parker.

Jack Poe had come to the Terrace with a strong resume: He had worked as a lookout and a bodyguard at nightclubs on Jacksboro Highway, as a youth had been befriended by Bonnie and Clyde and had tagged along with them as they cased a few banks.

Browning had hired Poe to care for his racehorses. But Poe was promoted to work in the casino.

“My job was to satisfy the people shooting dice and gambling,” Poe recalled. “Anything they wanted, I made sure they got it.”

“Anything” included prostitutes. The women, described by Poe as “very high-class ladies,” lived—and worked—in a two-story building behind the casino.

The shadows cast by the big oaks of Top o’ Hill Terrace hid the casino’s darker side, Poe claimed. “The worst thing I ever saw at Top o’ Hill was bodies laying down on the creek behind the place. They had been really tortured and died an awful death. One was still living.”

Poe did not ask any questions about what he had seen. And with good reason: “Lots of people got killed there, mostly for talking.”

If the Terrace had a dark side, it also was known for its honest gaming. Browning monitored people in the gaming room through two-way mirrors. And Browning, himself a gambler who knew what it was to lose, was said to never let a patron leave the Terrace broke.

As important as Browning’s reputation for honesty was to his success, just as important were the security and discretion he provided to his patrons.

His Top o’ Hill Terrace was an upholstered fortress.

For starters, two armed men were stationed at a guardhouse (see photos in Part 2) at the only entrance on the highway. Patrons had to show their ID and give the password to be allowed past the guardhouse.

The grounds were surrounded by an eight-foot chain-link fence wired to a security alarm.

The grounds were said to be patrolled by armed men accompanied by dogs wearing spiked collars.

The windows of the casino building had steel shutters.

Floors had trapdoors; walls hid secret rooms and passageways.

Browning and his Terrace had many powerful friends. But they also had powerful enemies: law enforcement and J. Frank Norris, pastor of First Baptist Church and co-founder of Bible Baptist Seminary (now Arlington Baptist University).

Just as Norris and law enforcement had waged a war against Hell’s Half Acre, so they waged a war against the Terrace.

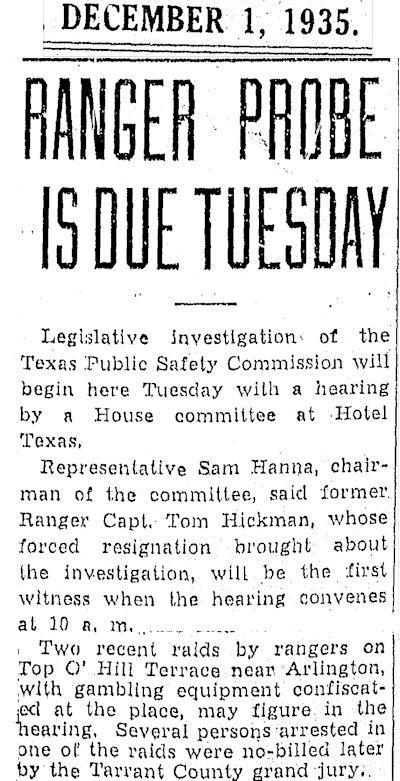

Thus, despite Browning’s precautions—and payoffs and tipoffs—the Terrace was raided occasionally.

Thus, despite Browning’s precautions—and payoffs and tipoffs—the Terrace was raided occasionally.

When raiders arrived at the guardhouse, the guards had to let them pass, of course, but only after a guard had stepped on a pin in the ground near the gate. Depressing that pin activated a buzzer in the casino, alerting Browning and employees. On one wall of the gaming room was what appeared to be an electrical outlet. Inserting a knife blade into the outlet opened a door to a hidden closet where gaming equipment—roulette wheels, slot machines, gaming tables—was stowed when the buzzer signaled a raid.

When all worked as planned, by the time raiders reached the gaming room, patrons were sipping tea and playing gin rummy in what had been transformed into a dining room; employees were innocently lounging about, sometimes singing hymns.

The outside entrance to the gaming room was at the rear of the building, away from the highway. Persons getting past that outside door faced five more doors, each with an armed guard, before reaching the gaming room in the basement.

Browning also had installed a forty-foot concrete tunnel (see photos in Part 2) connecting the gaming room to a wooded area west of the casino building. When raided, patrons could be evacuated through the tunnel to the outside and wait out the raid in the nearby tea garden.

“When there was a raid,” Jack Poe recalled, “we would hide the gambling tables in the wall and go out the tunnel. They would already have drinks and food set up in the tea garden. Like there was nothing bad going on. I had no idea who some of those important people were. Mr. Browning always made sure their names never became public, even after the raids.”

(And, yes, during one raid a prominent Fort Worth businessman got “stuck” in the tunnel, encumbered by the cast on his leg.)

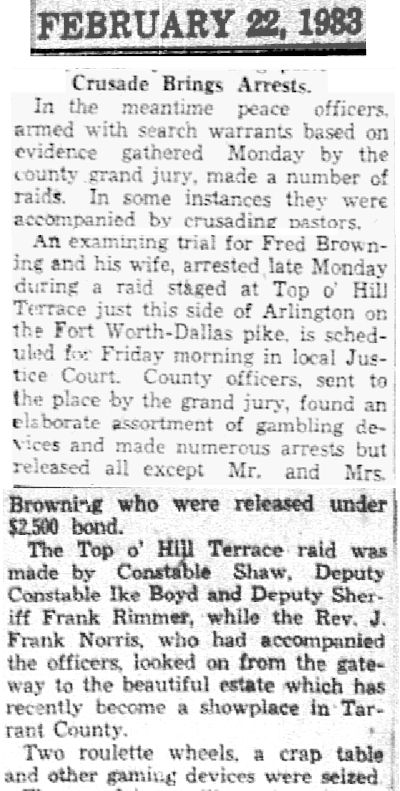

J. Frank Norris himself took part—sorta—in at least one raid. In 1933 Norris, two deputy sheriffs, and a constable arrived at the guardhouse. Norris stayed behind as the lawmen went ahead and forced their way into the casino in the basement and confiscated two roulette wheels, two gaming tables, poker chips, and dice.

J. Frank Norris himself took part—sorta—in at least one raid. In 1933 Norris, two deputy sheriffs, and a constable arrived at the guardhouse. Norris stayed behind as the lawmen went ahead and forced their way into the casino in the basement and confiscated two roulette wheels, two gaming tables, poker chips, and dice.

But a grand jury declined to indict Browning, and his roulette wheels were soon spinning again.

But a grand jury declined to indict Browning, and his roulette wheels were soon spinning again.

Norris was outraged. According to T. Lindsay Baker in Gangster Tour of Texas, Norris swore that one day the Baptists would own Top o’ Hill Terrace.

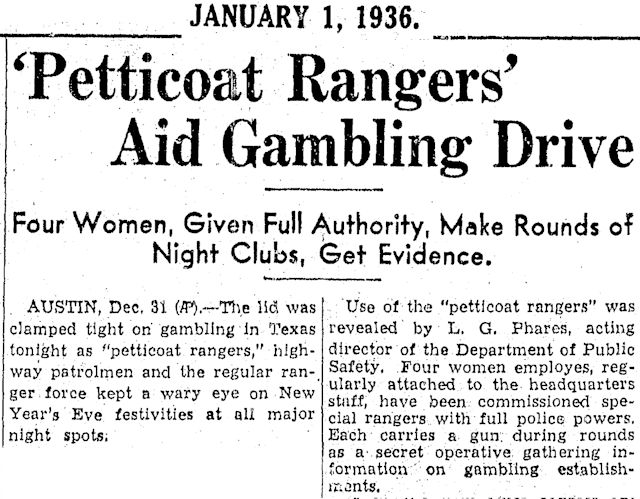

Amid the rich and famous patrons at the Terrace, occasionally there appeared patrons who were not what they seemed to be.

Amid the rich and famous patrons at the Terrace, occasionally there appeared patrons who were not what they seemed to be.

Doris Edwards was the widow of state trooper Ed Wheeler, who was killed by Bonnie and Clyde in 1934.

After Ed was killed, Harry Hines, the state highway commissioner (for whom the Dallas boulevard is named), got Doris a job as a secretary for the Texas Highway Patrol headquarters.

“Governor James Allred was violently opposed to gambling,” Mrs. Edwards recalled. “He contacted the chief of the highway patrol to see if there were any women on the staff who could help out the Texas Rangers.”

Four women were selected, trained, and became known as the “Petticoat Rangers.”

They accompanied undercover officers to establishments where illegal gambling was suspected, including the Terrace in 1935.

“I’d go in with my partner,” Mrs. Edwards recalled. “If we saw gambling in progress, I would go to the telephone and call the Rangers. ‘We’re having such a nice time here,’ I’d say. ‘Why don’t you join us.’ Then the Rangers would raid the place.”

In 1936 a judge ordered the destruction of $7,000 worth of gambling equipment seized in two raids in 1935.

In 1936 a judge ordered the destruction of $7,000 worth of gambling equipment seized in two raids in 1935.

In 1937 came another blow to the Terrace: The state legislature outlawed parimutuel betting. But by then the Terrace was established enough to survive on its own attractions.

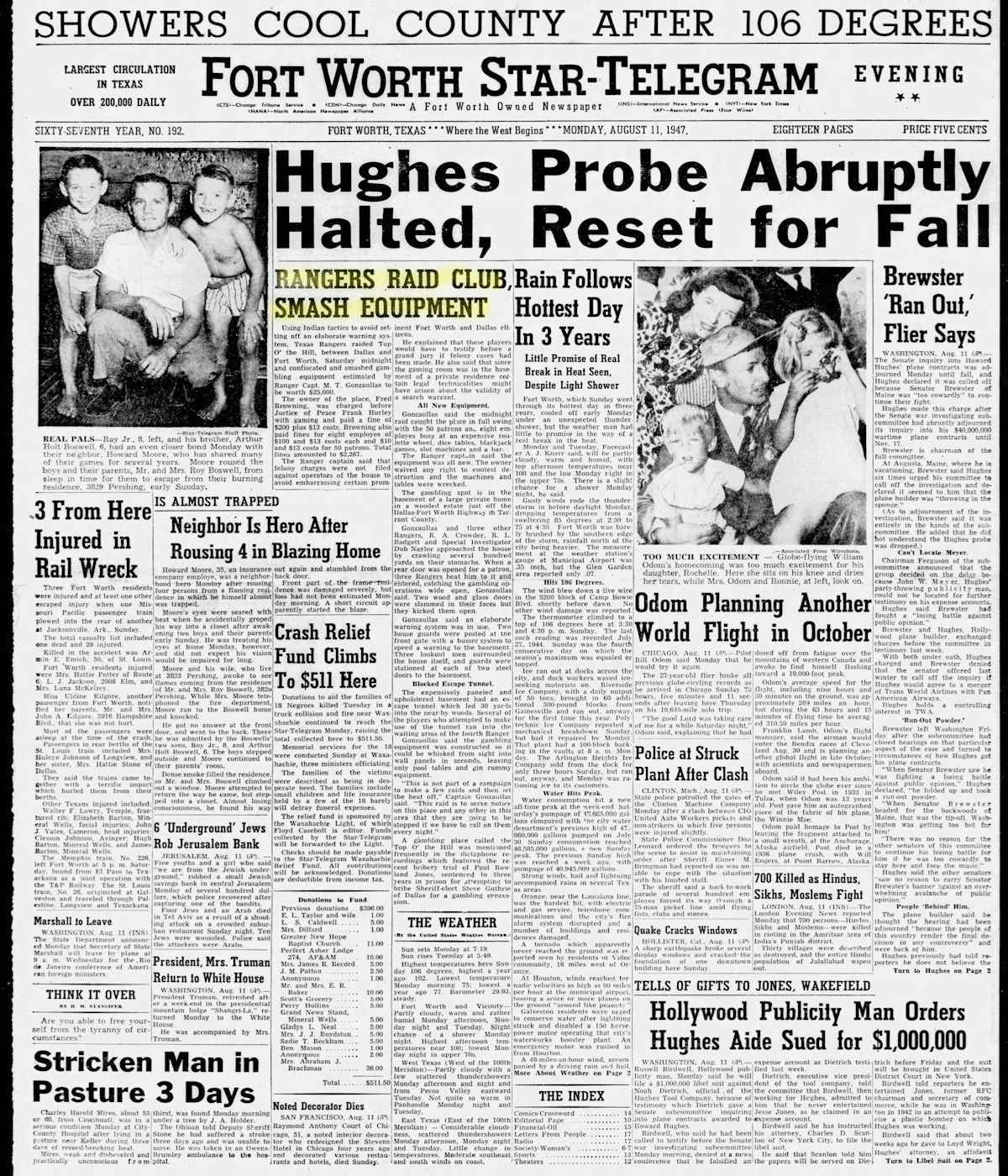

But ten years later came the big raid. In 1947 Texas Rangers Captain Manuel T. “Lone Wolf” Gonzaullas and three men bypassed the Terrace’s guardhouse at the highway and instead crawled on their bellies up the side of the hill and through the woods in the dark to the casino. Then they slipped into the entrance to the casino, which was at the rear of the building, and were down the stairs and into the gaming room before employees could react. There had been no buzzer to warn of a raid. The raiders caught fifty patrons inflagrante at the tables. Those patrons who fled into the tunnel found a Ranger waiting for them at its mouth.

But ten years later came the big raid. In 1947 Texas Rangers Captain Manuel T. “Lone Wolf” Gonzaullas and three men bypassed the Terrace’s guardhouse at the highway and instead crawled on their bellies up the side of the hill and through the woods in the dark to the casino. Then they slipped into the entrance to the casino, which was at the rear of the building, and were down the stairs and into the gaming room before employees could react. There had been no buzzer to warn of a raid. The raiders caught fifty patrons inflagrante at the tables. Those patrons who fled into the tunnel found a Ranger waiting for them at its mouth.

The gaming equipment was seized and later destroyed, but Gonzaullas said he filed only misdemeanor charges against Browning, employees, and patrons to avoid embarrassing “prominent Fort Worth and Dallas citizens,” who might have to testify before a grand jury if felony charges were filed.

More sternly, Gonzaullas warned that the Rangers would shut down gambling casinos “if we have to call on them every night.”

That put the Terrace on notice, and it began a slow decline. The law and Norris kept up the public pressure.

By the late 1940s gambler Benny Binion had become Browning’s partner in the Terrace.

In 1951 Binion opened his Horseshoe casino in Las Vegas reportedly with profits from the Terrace.

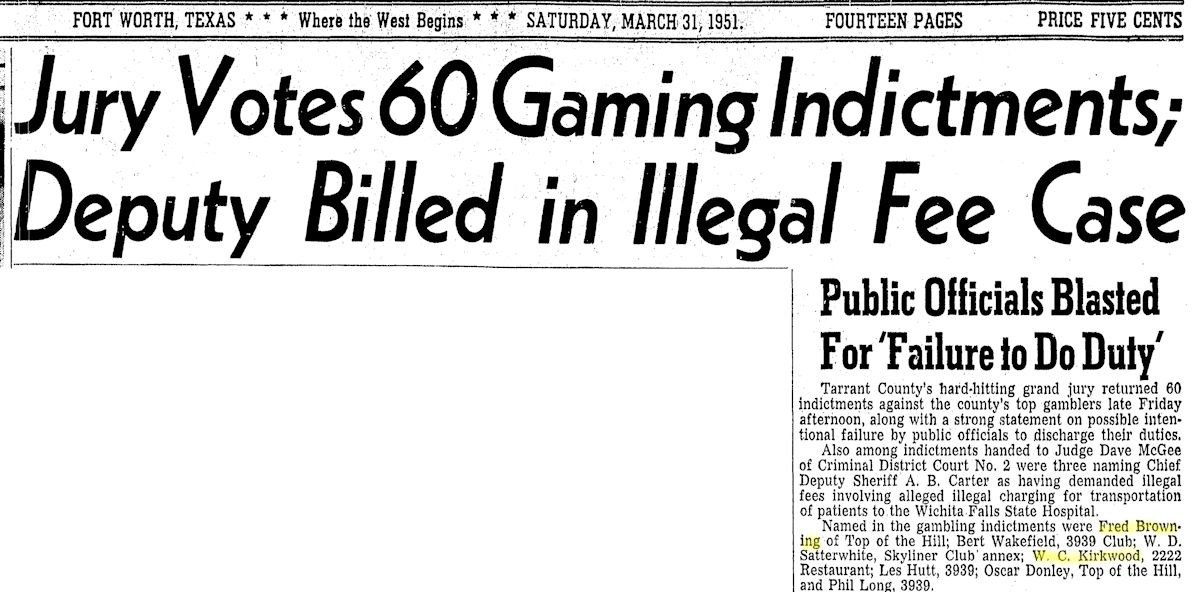

Browning (along with Pappy Kirkwood) was charged with gambling a few times in the early fifties. Browning and Kirkwood paid their fines and went about their business.

Browning (along with Pappy Kirkwood) was charged with gambling a few times in the early fifties. Browning and Kirkwood paid their fines and went about their business.

But Binion and Browning eventually caved to the pressure. Top o’ Hill Terrace closed.

J. Frank Norris’s forces had won the war of values.

Norris did not live to celebrate long. Browning did not live to mourn long.

Norris died in 1952.

Norris died in 1952.

Browning died in 1953.

Browning died in 1953.

The war over, the generals dead, the next stage was occupation of the contested territory by the conquering army:

Top o’ Hill Terrace (Part 2): Occupation

Posts About Crime Indexed by Decade

Posts About Religion

nevermind i found your book and your name lol.

We hope you enjoyed Mike’s book - Lost Ft Worth. As you know he was quite remarkable with his extensive study of Ft Worth.

hey im a student at Texas Weslyan university and this has been very helpful to my research for my essay over top o’hill terrace.I was wondering if I can get your name for my citations/references. This would be extremely helpful,thank you.

Thank you for visiting the site. Unfortunately the author, Mike Nichols, passed away and we are working on how best to preserve this informative site.

I really enjoyed the two part series. Great job! Can you please email me? I have a true crime / mafia podcast and have a couple of things I want to ask you please. I am an Arlington Baptist University alumni and attended in 1993-1995 before getting my History degree at Dallas Baptist University.

Thanks for visiting the site- unfortunately the author, Mike Nichols, passed away. We are working on a solution and will post when we have more information. Thanks for your patience.

I have been on the tour. If they are still doing it..it is worth a drive over to Arlington.

I’VE BEEN there many yrs ago and spoke with some of the nuns that explained alot including the hidden get away tunnel and the lookout from the hill to see the feds coming from Ft worth for dusty miles since the road wasn’t paved.

Can you post a link to Part 1? I just an across this and would like to start from the beginning.

Tulane, the link to Part 2 is at the bottom of Part 1. There is a link to Part 1 at the top of Part 2.