Police officers are probably no more superstitious than members of other professions: Baseball players don’t talk about a no-hitter while the game is in progress; actors don’t say the play title Macbeth in a theater; pilots don’t pose for a photo in front of an airplane before a flight; journalists don’t whistle in the newsroom.

And some superstitions are almost universal. For example, many people think the number 13 brings bad luck.

Some of those people were early Fort Worth police officers who noticed that bad luck seemed to befall officers who wore badge no. 13.

Of course, a badge number itself doesn’t draw danger to a police officer. But the badge does—as soon as its wearer pins it on and takes an oath “to protect and to serve.”

Nonetheless, these five officers wore badge no. 13:

Lee Waller

The badges of the Fort Worth police department were not numbered until about 1891. City Marshal James Maddox assigned the new numbered badges on the basis of seniority, with badge no. 1 going to the senior officer, and badge no. 13 going to a relative rookie: twenty-three-year-old Lee Waller.

Maddox later said: “The boys jested more or less about the number being an unlucky one, but Waller did not seem to mind wearing it.”

Relative rookie or not, officer Waller, with partner H. C. Townes, was assigned to the beat that the Dallas Morning News called “the very lowest and toughest district of the city”: Hell’s Half Acre.

On the night of June 28 Waller and Townes were patrolling in the Acre when they saw a man and a woman in an alley on East 12th Street.

Officer Townes would later testify that the man and woman were two African Americans, Lou Davis and Jim Burris, alias “Jim Toots.”

Officer Townes later testified: “We were walking along Twelfth and when we got to the alley we saw Toots and Lou Davis, a negro woman, about seven or eight feet from the sidewalk. . . . Lou Davis is a negro prostitute. She was standing with her arms on Toots’s shoulder or around his neck. . . . When Waller saw them he told Lou to come out. Toots said, ‘What’s the matter with you; I’ll be shoving a rock out there after you.’ ‘I’ll be shoving something else back at you,’ Waller replied.”

Except, local historians Dr. Richard Selcer and Kevin Foster write in Written in Blood: The History of Fort Worth’s Fallen Lawmen (Volume 1), black prostitute Lou Davis was white police officer Lee Waller’s “paramour.”

Officer Townes testified that there in that alley Waller and Toots cursed each other. A scuffle ensued. Waller struck Toots with his nightstick. Townes intervened; Toots retreated down the street.

Jim Toots, Selcer and Foster write, began looking for a gun and some reinforcements among the Acre’s African-American population. Lou Overton, who owned an African-American saloon on Rusk (now Commerce) Street in the Acre, testified: “Toots was out in the street cursing the officers and making threats that he would kill the brass-buttoned sons of bitches; that they couldn’t walk their beats and live . . . that he didn’t have an even break with them.”

Toots finally procured a pistol from an unlikely donor: Fort Worth police officer Tom Snow, who moonlighted as a bartender in the Acre. Toots also enlisted Horace Bell and Willie Campbell, two black men of the Acre who had reason to resent the way they had been treated by white policemen.

Meanwhile, officers Waller and Townes recruited their own reinforcement—officer Frank Bryant—and began searching the Acre for Toots. Soon, just after midnight (on June 29), Waller and company were walking south on Rusk; Jim Toots and company were walking north on Rusk. Toots and company shot first, Selcer and Foster write, taking the three officers by surprise near the Southern Livery Stables (about where Commerce Street today curves around the Convention Center dome).

Amazingly, with two three-man teams firing at each other, only Waller was hit. And he was hit three times. Toots and his men fled. Officer Townes helped Waller walk to the firehouse on Main Street. Waller collapsed from his wounds and exclaimed, the Dallas Morning News said, “Boys, I’m a goner.” (The Morning News account contains some inaccuracies.)

Amazingly, with two three-man teams firing at each other, only Waller was hit. And he was hit three times. Toots and his men fled. Officer Townes helped Waller walk to the firehouse on Main Street. Waller collapsed from his wounds and exclaimed, the Dallas Morning News said, “Boys, I’m a goner.” (The Morning News account contains some inaccuracies.)

Officer Waller and badge no. 13 were rushed to the Missouri Pacific Infirmary in the care of Dr. William A. Duringer. Waller died on June 30.

Robert Rice

Fast-forward to 1895. Officer Robert Rice, wearing badge no. 13, on the night of January 5 was patrolling the Texas & Pacific yard when a train arrived from Dallas. A man jumped from a boxcar. Rice ordered him to halt. The man ran, and Rice pursued him. Suddenly the man stopped and fired at Rice. The Dallas Morning News reported that Rice was “mortally wounded.”

Fast-forward to 1895. Officer Robert Rice, wearing badge no. 13, on the night of January 5 was patrolling the Texas & Pacific yard when a train arrived from Dallas. A man jumped from a boxcar. Rice ordered him to halt. The man ran, and Rice pursued him. Suddenly the man stopped and fired at Rice. The Dallas Morning News reported that Rice was “mortally wounded.”

However, Rice survived.

In 1902 the Fort Worth Register wrote that after officer Rice left the police force he moved to Galveston, where he lost everything in the hurricane of 1900.

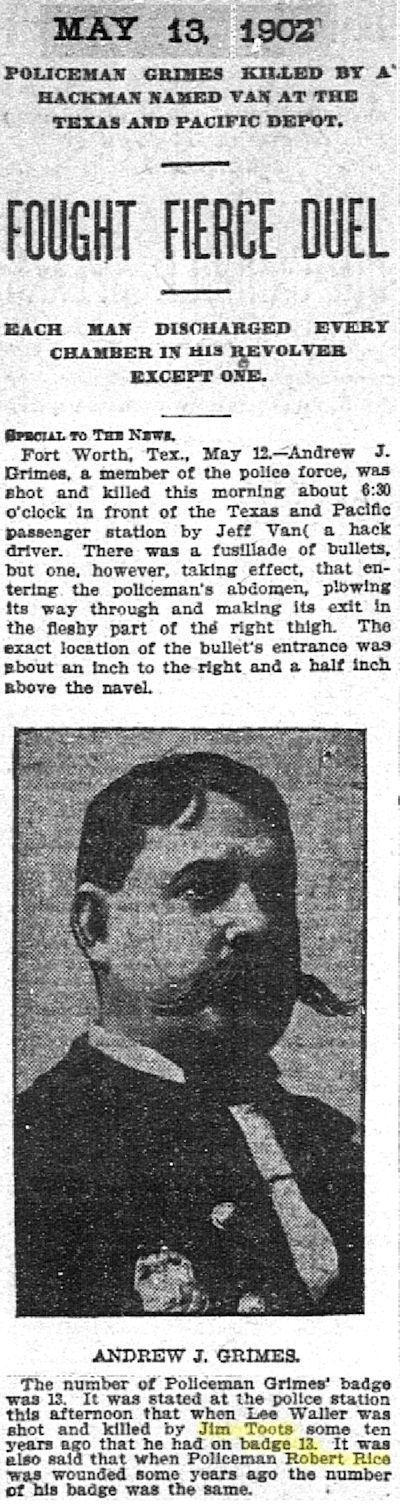

Andrew Grimes

On the morning of May 12, 1902 officer Andrew Grimes was on patrol at the Texas & Pacific passenger station when he saw hack (horse-drawn cab) driver Jeff Van parked in a “no parking” zone. Grimes told Van to move his hack. Van refused. An argument ensued. Grimes threatened to arrest Van.

Witnesses disagreed on what happened next—which man fired first. But nine shots were exchanged, and officer Grimes was shot to death. Police officer Joe Witcher and station master John J. Fulford disarmed Van.

Witnesses disagreed on what happened next—which man fired first. But nine shots were exchanged, and officer Grimes was shot to death. Police officer Joe Witcher and station master John J. Fulford disarmed Van.

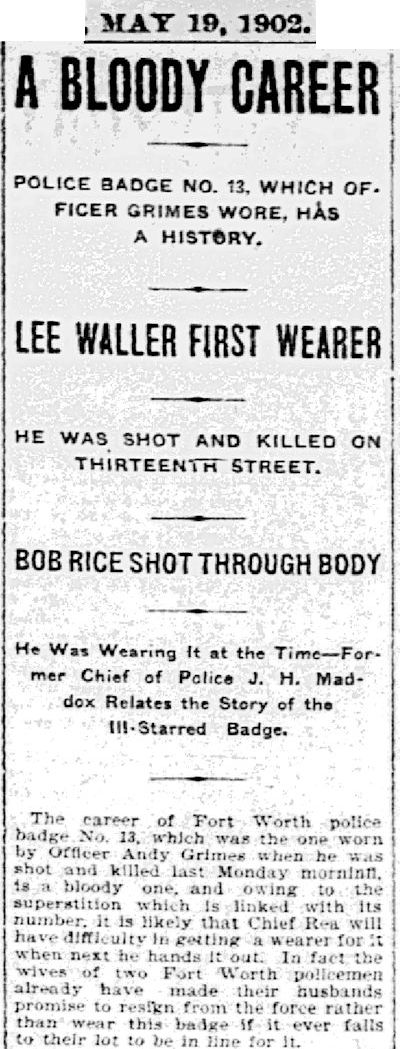

The Dallas Morning News noted that officers Waller and Rice, like Grimes, had worn badge no. 13.

The Dallas Morning News noted that officers Waller and Rice, like Grimes, had worn badge no. 13.

The Fort Worth Register, in chronicling the “bloody history” of badge no. 13, also noted that officers Waller and Rice had worn the badge and that officer Grimes was the thirteenth officer to wear badge no. 13. He was buried on the day after he was shot: May 13.

The Fort Worth Register, in chronicling the “bloody history” of badge no. 13, also noted that officers Waller and Rice had worn the badge and that officer Grimes was the thirteenth officer to wear badge no. 13. He was buried on the day after he was shot: May 13.

The Register also pointed out that officer Lee Waller had been killed on 13th Street at its intersection with Rusk Street.

The Register wrote that “the wives of two Fort Worth policemen have made their husbands promise to resign from the force rather than wear this badge” and “it is likely that Chief [William] Rea will have difficulty in getting a wearer for it when next he hands it out.”

James W. Thomason

But Rea had no such difficulty. Badge no. 13 went to James W. Thomason—and not because Thomason ranked thirteenth in seniority. In fact, by 1905 Thomason had been first a Fort Worth officer and then a detective for at least twenty years.

Thomason and Rea had known each other from way back: Thomason had roomed with Rea in 1885 when Rea was city marshal.

Thomason and Rea had known each other from way back: Thomason had roomed with Rea in 1885 when Rea was city marshal.

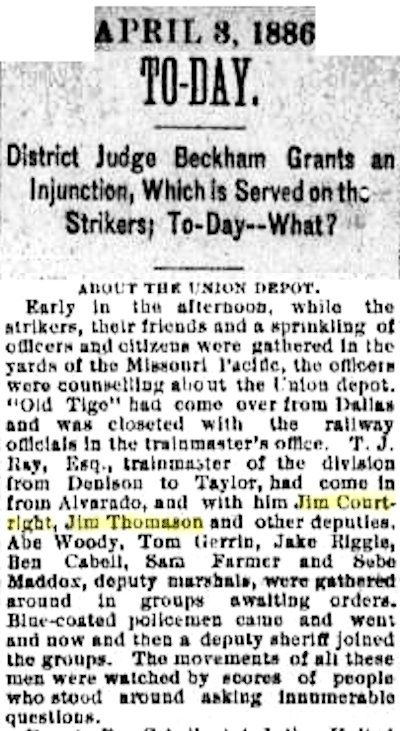

In 1886 during the rail strike Thomason had taken part in the Battle of Buttermilk Junction along with Jim Courtright and John J. Fulford.

In 1886 during the rail strike Thomason had taken part in the Battle of Buttermilk Junction along with Jim Courtright and John J. Fulford.

According to retired Fort Worth police sergeant and historian Kevin Foster, in 1905 Thomason, wearing badge no. 13, was escorting a prisoner to Dallas on the interurban when the prisoner tried to escape. A struggle ensued, and before the prisoner could be subdued, he ripped badge no. 13 from Thomason’s uniform and threw it out the window of the train.

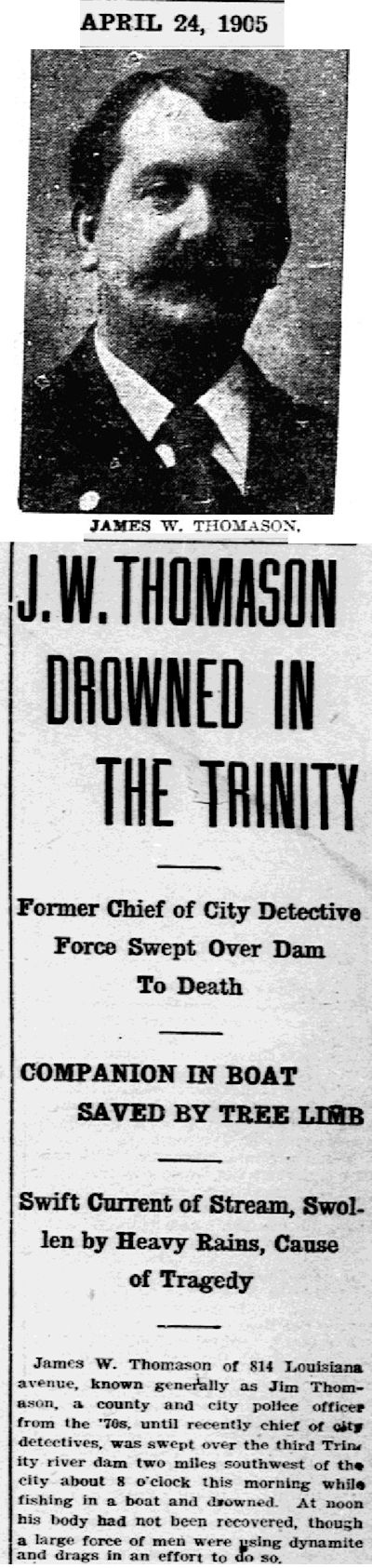

One week later, on April 24, Thomason went fishing on the Clear Fork of the Trinity River with three friends. Rain had fallen overnight, and the river was running high as Thomason and John Johnson put their boat into the river above city dam no. 3, located near the Texas & Pacific bridge over the river. As the pair fished, their boat drifted downstream in the strong current. The other two friends, fishing on the bank, saw that the boat was drifting dangerously close to the dam, submerged in rushing water. The two friends shouted an alarm to Thomason and Johnson. As the boat was about to be swept over the dam, Johnson grabbed an overhanging tree limb and climbed to safety. Just as the boat shot over the dam, Thomason jumped from the boat and was swept over the dam and into the whirlpool at the bottom.

As Thomason was swept downstream, trying to swim against the strong current, his friends ran alongside the river bank. His friends lost sight of him about four hundred yards below the dam.

Seventy-five men, including Police Chief James Maddox, began the search for Thomason’s body. Searchers feared that Thomason had hit his head on the concrete dam as he was swept over and had been rendered unable to swim well enough to reach shore downstream. Men, tethered to the bank by ropes, ventured into the strong current to search for Thomason. Others in boats dragged the river with nets. Searchers detonated dynamite to try to raise the body to the surface. Men monitored the other city dams downstream. Foster says men at Randol Mill several miles downstream in Arlington strung nets along the dam there and kept watch.

Seventy-five men, including Police Chief James Maddox, began the search for Thomason’s body. Searchers feared that Thomason had hit his head on the concrete dam as he was swept over and had been rendered unable to swim well enough to reach shore downstream. Men, tethered to the bank by ropes, ventured into the strong current to search for Thomason. Others in boats dragged the river with nets. Searchers detonated dynamite to try to raise the body to the surface. Men monitored the other city dams downstream. Foster says men at Randol Mill several miles downstream in Arlington strung nets along the dam there and kept watch.

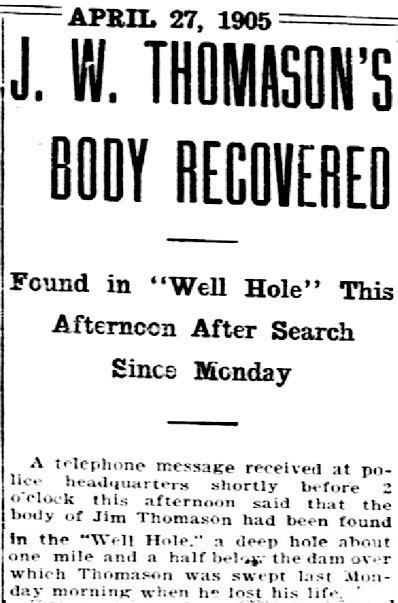

Not until April 27 was the body of officer Thomason found, snagged on a submerged barbed wire fence near dam no. 2 in the Well Hole, a deep hole in the riverbed about one and a half miles below dam no. 3.

Not until April 27 was the body of officer Thomason found, snagged on a submerged barbed wire fence near dam no. 2 in the Well Hole, a deep hole in the riverbed about one and a half miles below dam no. 3.

Meanwhile, in 1905 the police department issued new badges, Foster says, but new or not, every officer refused to wear badge no. 13.

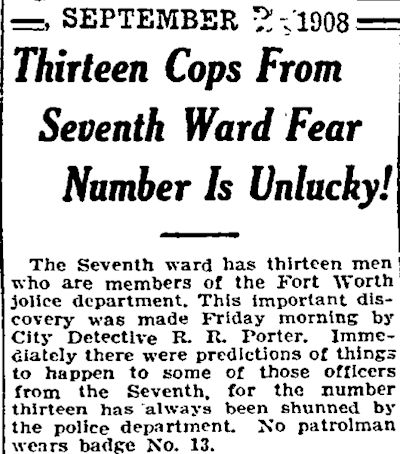

Three years later the Telegram reported that the thirteen officers of the Seventh Ward (South Side) expressed concern that their head count would bring bad luck despite the fact that their ward number is thought to bring good luck.

Three years later the Telegram reported that the thirteen officers of the Seventh Ward (South Side) expressed concern that their head count would bring bad luck despite the fact that their ward number is thought to bring good luck.

The Telegram wrote that “the number thirteen has always been shunned by the police department. No patrolman wears badge No. 13.”

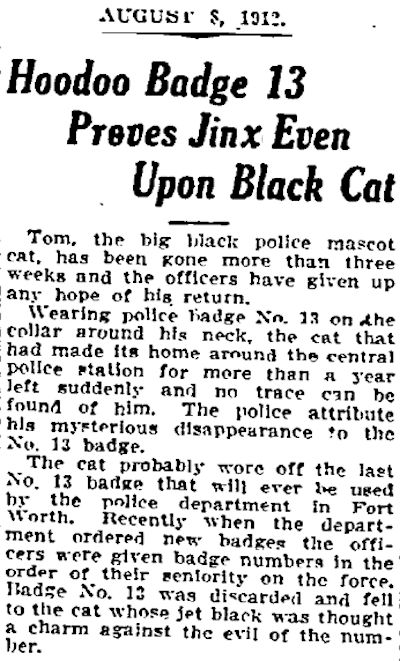

In 1912, Foster says, new badges were again issued: the “panther badge” still worn today. Again a badge no. 13 was among the new badges, but every officer refused to wear it.

But Tom, the mascot of the central police station, wasn’t superstitious. He wore the old badge no. 13, taken out of service when the panther badges were issued.

But Tom, the mascot of the central police station, wasn’t superstitious. He wore the old badge no. 13, taken out of service when the panther badges were issued.

“Badge No. 13 was discarded and fell to the cat whose jet black was thought a charm against the evil of the number,” the Star-Telegram wrote.

But then Tom and old badge no. 13 disappeared, leaving no forwarding address. “The police attribute his mysterious disappearance to the No. 13 badge.”

Pete Howard

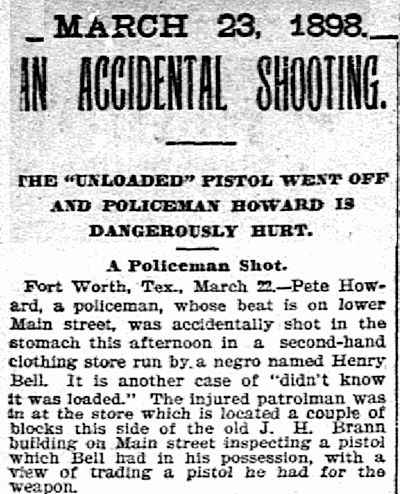

In 1898 officer Pete Howard was in a shop on Main Street looking at a pistol he was considering trading his own pistol for. He unloaded his pistol and placed it atop the counter. The store clerk handed Howard the pistol Howard was interested in and turned away to attend to another matter. When the clerk returned to Howard, the clerk picked up Howard’s pistol and inspected it, unaware, the Dallas Morning News wrote, that Howard had reloaded it.

In 1898 officer Pete Howard was in a shop on Main Street looking at a pistol he was considering trading his own pistol for. He unloaded his pistol and placed it atop the counter. The store clerk handed Howard the pistol Howard was interested in and turned away to attend to another matter. When the clerk returned to Howard, the clerk picked up Howard’s pistol and inspected it, unaware, the Dallas Morning News wrote, that Howard had reloaded it.

The gun discharged, hitting Howard in the stomach.

He survived.

In 1902 former Police Chief James Maddox recalled the incident, saying that Howard had worn badge no. 13 “for a year and was shot the day after he took it off.” (Those skeptical about superstition might say, “Aha! Officer Howard wore badge no. 13 without incident for a year. After he took it off, he was shot. So why not argue that badge no. 13 brought him good luck for a year?”)

Fast-forward to 1915. Officer Howard was patrolling Battercake Flats, a beat almost as tough as the Acre that officer Waller had patrolled in 1892.

Battercake Flats was what today might be called a “slum” or “ghetto”: an enclave of outgroups. Ironically Battercake Flats was located practically the back yard of two bastions of the ingroup power structure: the courthouse and the county jail. The Flats was a wedge of land bounded by West Belknap Street and the Trinity River, stretching from the bluff behind the courthouse west past the confluence of the Clear and West forks of the river.

Many of the homes in the Flats were Frankenshanties, built with scavenged building materials and improvisation. Discarded tarps or sheet metal panels might do for a roof; three dry-goods boxes might constitute a living room suite. Many of the homes were doorless, windowless shells without electricity, gas, or water.

Battercake Flats’ population was mostly African Americans with a small Hispanic population and a minuscule white population. Most residents of the Flats, like most residents of other outgroup enclaves, were decent people just trying to get by. But many residents of the Flats were squatters living, the Star-Telegram reminded, “in the land of free rents and no taxes.” Many were low-wage unskilled laborers, migrant workers (for example, cotton pickers), unemployed or unemployable. And the Flats certainly had a criminal element: drunk and disorderlies, sneak thieves, armed robbers, prostitutes, people who were wanted for more serious crimes. (Enclaves make a good hideout.)

Indeed, Battercake Flats, for its small footprint, had one of the highest crime rates in the city. Its Franklin Street—two blocks from the county jail—was one of the meanest streets in Cowtown for a policeman.

On Franklin Street on the night of August 16, 1915 two men fatally stabbed officer Pete Howard. Police at first sought their “usual suspects” among the Hispanic population but quickly switched to the African-American population. Just to hedge their bets, police conducting a dragnet of “resorts” in Battercake Flats and Irish Town (another outgroup enclave) rounded up 120 people both brown and black.

On Franklin Street on the night of August 16, 1915 two men fatally stabbed officer Pete Howard. Police at first sought their “usual suspects” among the Hispanic population but quickly switched to the African-American population. Just to hedge their bets, police conducting a dragnet of “resorts” in Battercake Flats and Irish Town (another outgroup enclave) rounded up 120 people both brown and black.

Ultimately police would determine that two men—Luis Flores and Jose Estapa—killed officer Howard. Flores received a life sentence.

In the years since these five officers made the news, badge no. 13 has been worn without repeating its “bloody history,” Foster says. But as this wall in Trinity Park shows, it’s the badge, not the number, that draws danger.

In the years since these five officers made the news, badge no. 13 has been worn without repeating its “bloody history,” Foster says. But as this wall in Trinity Park shows, it’s the badge, not the number, that draws danger.

(Thanks to retired Fort Worth police sergeant and historian Kevin Foster for his help.)