On November 27, 1917 two men—Will and Tom—and one woman—Minnie—left the North Side individually and at different times.

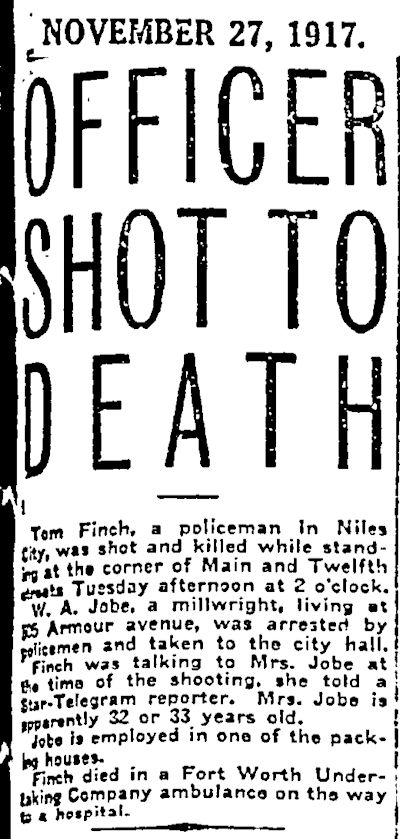

About 2:30 p.m. their paths converged four miles south: The three encountered each other on a sidewalk.

Will’s encounter with Tom and Minnie was intentional. Minnie claimed that her encounter with Tom was pure chance. Will didn’t believe her. And his opinion was the only one that mattered: He had the gun.

Let us turn back the clock two hours. William A. Jobe, a millwright at the packing plants, had received a phone call at work: A neighbor told Jobe that someone had phoned for his wife Minnie at the neighbor’s house but that Mrs. Jobe had gone to downtown Fort Worth.

Upon hearing that, Jobe left the packing plant.

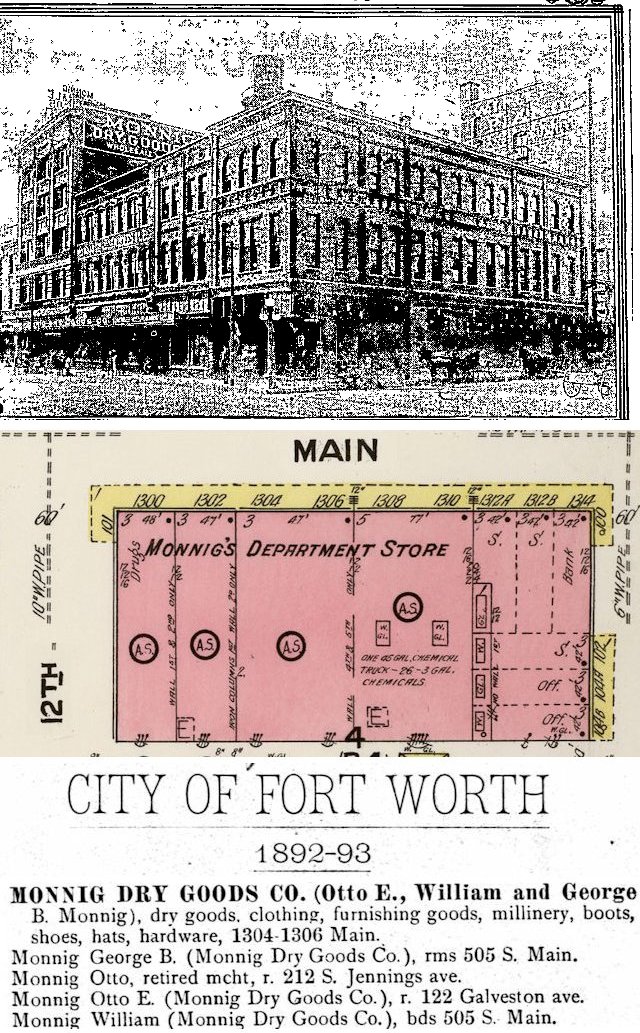

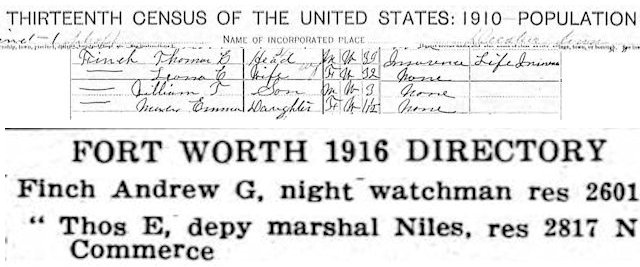

Meanwhile Mrs. Jobe was indeed downtown, shopping at Monnig’s Department Store at 1300 Main Street (where the convention center is today).

Monnig’s had not yet relocated to 500 Houston Street. But by 1917 Monnig’s had been at 1300 Main a long time.

Monnig’s had not yet relocated to 500 Houston Street. But by 1917 Monnig’s had been at 1300 Main a long time.

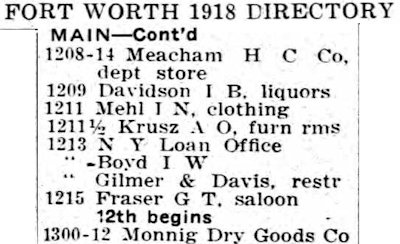

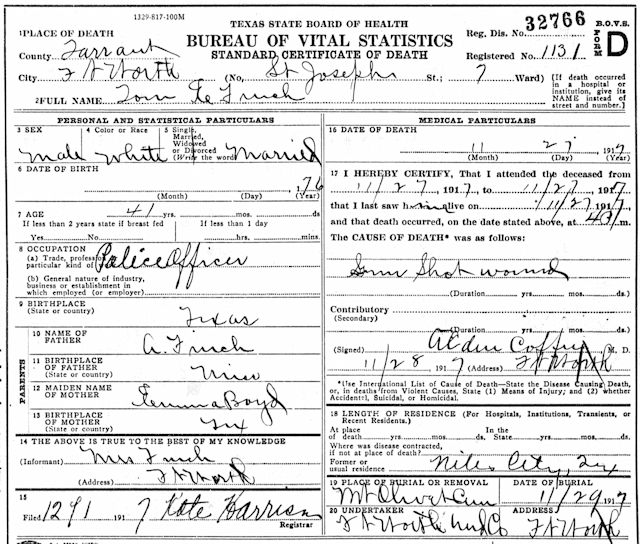

Also downtown that afternoon was Tom Finch. Finch had been a life insurance salesman. But in 1911 Tom Finch had stopped ensuring risks and became a risk: He joined the Niles City police force about the time the wealthy enclave incorporated.

Also downtown that afternoon was Tom Finch. Finch had been a life insurance salesman. But in 1911 Tom Finch had stopped ensuring risks and became a risk: He joined the Niles City police force about the time the wealthy enclave incorporated.

Tom Finch and the Jobes lived within a few blocks of each other in Fostepco Heights north of Niles City, which encompassed the stockyards and packing plants.

Tom Finch, too, had been in Monnig’s that afternoon. He had just paid his bill and left the store. On the sidewalk outside the store he encountered Mrs. Jobe, who was window shopping.

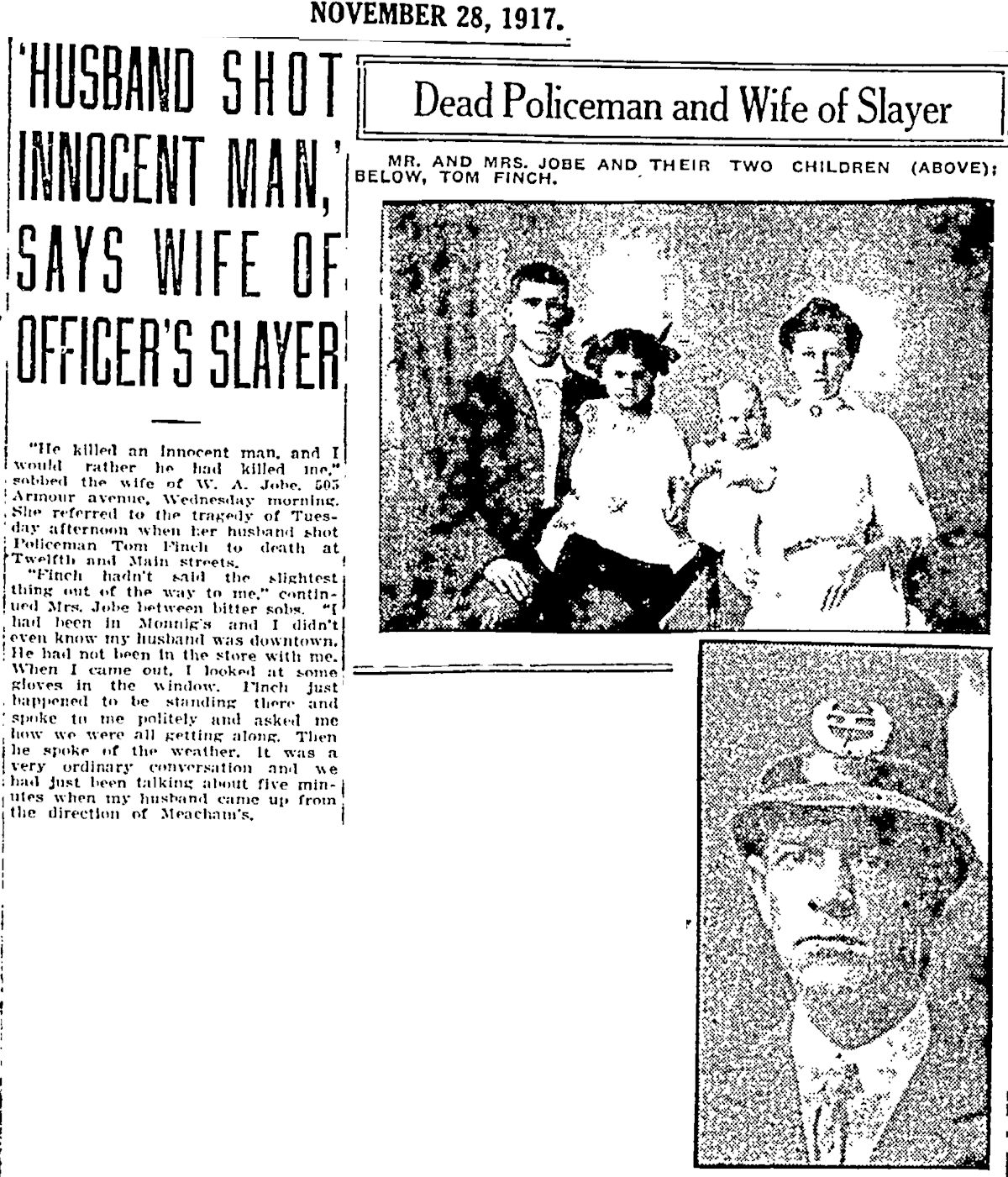

“When I came out,” Mrs. Jobe later said, “I looked at some gloves in the window. Finch just happened to be standing there and spoke to me politely and asked me how we were all getting along. Then he spoke of the weather. It was a very ordinary conversation and we had just been talking about five minutes when my husband came up from the direction of Meacham’s.”

Meacham’s Department Store was one block north of Monnig’s.

Meacham’s Department Store was one block north of Monnig’s.

Mrs. Jobe continued: “Finch started to speak to him [Will Jobe]. I saw my husband raise his gun and his face was as white as death and I knew he was angry. I turned my back. I couldn’t stand anymore and Finch fell.”

Passersby on the street and sidewalk screamed in horror at the sudden violence. People rushed out of nearby buildings. Horses were startled.

“My husband didn’t ask for any explanations or give Finch time to say a word. I was looking for him to kill me next, but he didn’t. . . . He killed an innocent man, and I would rather he had killed me,” she sobbed.

Tom Finch was not armed when Will Jobe shot him. Finch died on the way to a hospital.

Tom Finch was not armed when Will Jobe shot him. Finch died on the way to a hospital.

Jobe was arrested and charged with murder. He signed a confession.

Tom Finch had a wife and four children. The Jobes had two children.

Mrs. Jobe later said that her husband had left work at noon and apparently had gone downtown to find her. He knew that she often shopped at Monnig’s. She said that he had watched her on a number of occasions on account of his jealous suspicions and had upbraided her many times for transgressions of which she claimed she was innocent. Then, she said, he would try to conciliate her with gifts and tell her that he tormented her so only because he loved her.

Mrs. Jobe later said that her husband had left work at noon and apparently had gone downtown to find her. He knew that she often shopped at Monnig’s. She said that he had watched her on a number of occasions on account of his jealous suspicions and had upbraided her many times for transgressions of which she claimed she was innocent. Then, she said, he would try to conciliate her with gifts and tell her that he tormented her so only because he loved her.

“Finch hadn’t said the slightest thing out of the way to me,” continued Mrs. Jobe. “I had been in Monnig’s and I didn’t even know my husband was downtown. He had not been in the store with me.

“He has made my life so miserable with his jealousy. And without any cause. He is jealous of people whom I do not even know.

“But I shall not tell a lie on the innocent man. It is a sad, sad case. But I do not want any sympathy for myself. I feel sorry for his wife and family. My husband has never mentioned his dislike for Finch to me.”

Think about it: If Will Jobe was bound and determined to kill Tom Finch and wanted to get away with the crime, shooting Finch—a police officer!—on Main Street in broad daylight during business hours was not the optimum way.

How, you ask, could Jobe ever hope to get away with murder?

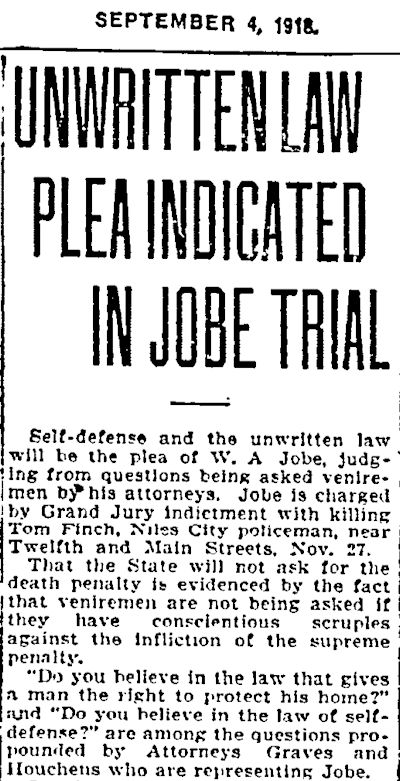

The answer is the unwritten law.

The answer is the unwritten law.

According to the Buffalo Law Review, the unwritten law was an uncodified constraint that protected “those who killed to defend the honor of women. . . . a husband, brother, or father could justifiably kill any man who had a sexual relationship outside of marriage with the killer’s wife, daughter, sister, or mother.”

The Review adds: “Criminal defendants who could convince a jury that they killed in defense of the sanctity of their home, and the virtue of their women, were almost certain to be acquitted.” (But the vice was not versa: The unwritten law seldom protected a wife who killed her husband’s lover.)

The unwritten law was used as a “get out of jail free” card for homicide mostly from the mid-nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth century. The unwritten law may not have been codified, but as a defense it could be as effective as any written law. For example, in addition to W. A. Jobe, these murder defendants invoked the unwritten law:

In 1912 during the byzantine Sneed-Boyce feud John Beal Sneed walked into the lobby of Fort Worth’s Metropolitan Hotel and shot to death cattleman A. G. Boyce Sr. as Boyce sat in a chair. Sneed later killed A. G. Boyce Jr. on a sidewalk in Amarillo. Sneed accused father and son of conspiring to take his wife from him. Sneed’s defense in court was, in part, the unwritten law.

He was acquitted both times.

In 1915 Fort Worth lawyer and aggrieved father Dee Estes pleaded the unwritten law after he killed a man who had been arrested for molesting Estes’s daughter. Estes shot and killed the suspect, who was in custody at the jail at the time as police officers looked on! Estes was acquitted.

In 1917 Reverend C. C. Reneau, jealous of one-legged W. N. Shaw’s attentions to Mrs. Reneau, fired his gun through a bedroom window and killed Shaw as Shaw sat alone in his room buckling on his artificial leg. Reneau pleaded the unwritten law and was no-billed by a grand jury.

Accordingly, Will Jobe’s defense team, to prepare for his trial for murder, selected jurors with the unwritten law in mind, asking jurors: “Do you believe in the law that gives a man the right to protect his home?”

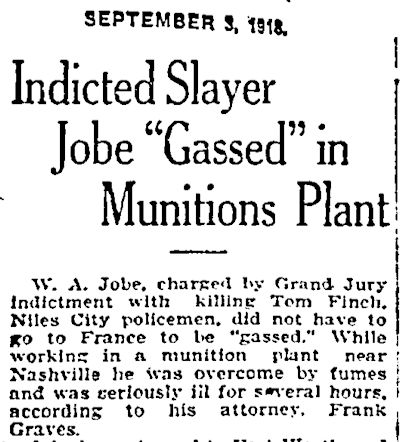

While free on bond and awaiting trial, Will Jobe was accidentally gassed while working at a munitions plant.

While free on bond and awaiting trial, Will Jobe was accidentally gassed while working at a munitions plant.

When Jobe’s trial began, the witness stand became a ducking stool, a public humiliation for husband and wife alike. Mrs. Jobe was confronted by witnesses produced by the defense who told “the story of her transgressions—the life she had led with the man who her husband killed.”

When Jobe’s trial began, the witness stand became a ducking stool, a public humiliation for husband and wife alike. Mrs. Jobe was confronted by witnesses produced by the defense who told “the story of her transgressions—the life she had led with the man who her husband killed.”

For example, Mrs. D. F. Finley of 821 Florence Street testified that two weeks before the killing, Tom Finch and Mrs. Jobe rented a room from her and occupied it and that Will Jobe was aware of that fact.

Such testimony forced Will Jobe’s wife to change her tune—from the “Wedding March” to “Runaround Sue.”

When asked by Assistant County Attorney Parker why she had previously stated that Finch was an “innocent man” and that she had never been intimate with him, Mrs. Jobe broke down and cried.

“I did not want to say anything that would reflect on him,” she said between sobs, “and I didn’t want people to know I had done that way.”

(Also representing the state was Assistant County Attorney Fritz G. Lanham, for whom the federal building is named.)

Mrs. Jobe testified that she had first met Tom Finch on a North Side streetcar and later went to a movie with him. She said that she later accompanied him to a room twice.

“Your husband knew of your relations with Finch?” asked defense attorney Frank Graves.

“Yes, sir,” she replied. “We were quarreling the night before the killing. He accused me of being with Mr. Finch. I told him I had and would be with him again.”

On the day of the killing Mrs. Jobe said she was starting to go downtown when her husband asked her where she was going. She said that she told him that she “didn’t know that it was anybody’s business.”

On cross-examination she admitted that she had sent word to Finch “that he looked good to me” and that she wanted to meet him.

“We met by accident,” Mrs. Jobe testified when asked how it was that Finch and she were together on the day of the shooting.

“We talked about five or ten minutes,” she continued, “and he wanted me to go to a room.”

“Had you agreed to go?”

“Yes, sir.”

She said that she knew that Finch was a husband and a father.

Several witnesses called by the defense refused to testify that Tom Finch had a bad reputation or that he “was bad on women.” Among them were W. H. Brown, mayor of Niles City, and Will Atherton, Niles City patrolman. (In 1922 Will Atherton would be charged—but later no-billed—in the lynching of Fred D. Rouse.)

That’s a gut-wrenching strategy for a defendant to use: His wife’s testimony that she was unfaithful to him with the man he killed provides the defendant with a defense under the unwritten law.

That’s a gut-wrenching strategy for a defendant to use: His wife’s testimony that she was unfaithful to him with the man he killed provides the defendant with a defense under the unwritten law.

But the strategy worked. Will Jobe was given a five-year suspended sentence and returned to work at the munitions plant.

Fourteen months later Mrs. Jobe filed for divorce.

Fourteen months later Mrs. Jobe filed for divorce.