On the morning of May 20, 1927 five hundred people at Roosevelt Field on Long Island watched mail pilot Charles Augustus Lindbergh take off in his monoplane Spirit of St Louis. He was bound for Paris. Alone. Nonstop. Such a flight had never been made before.

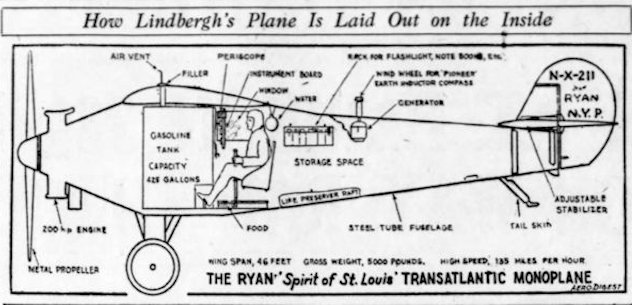

Lindbergh was traveling light: The fuselage of his airplane was made of treated fabric over a metal tube frame; the wings were made of fabric over a wood frame. He carried four sandwiches, two canteens of water, 425 gallons of gas—and no radio, no parachute.

Lindbergh was traveling light: The fuselage of his airplane was made of treated fabric over a metal tube frame; the wings were made of fabric over a wood frame. He carried four sandwiches, two canteens of water, 425 gallons of gas—and no radio, no parachute.

He also carried a nickname: the “Flying Fool.” (Photo from Wikipedia.)

Note that while flying the Spirit of St. Louis Lindbergh sat behind the gas tank and looked forward through a periscope. The airplane had no windshield.

Note that while flying the Spirit of St. Louis Lindbergh sat behind the gas tank and looked forward through a periscope. The airplane had no windshield.

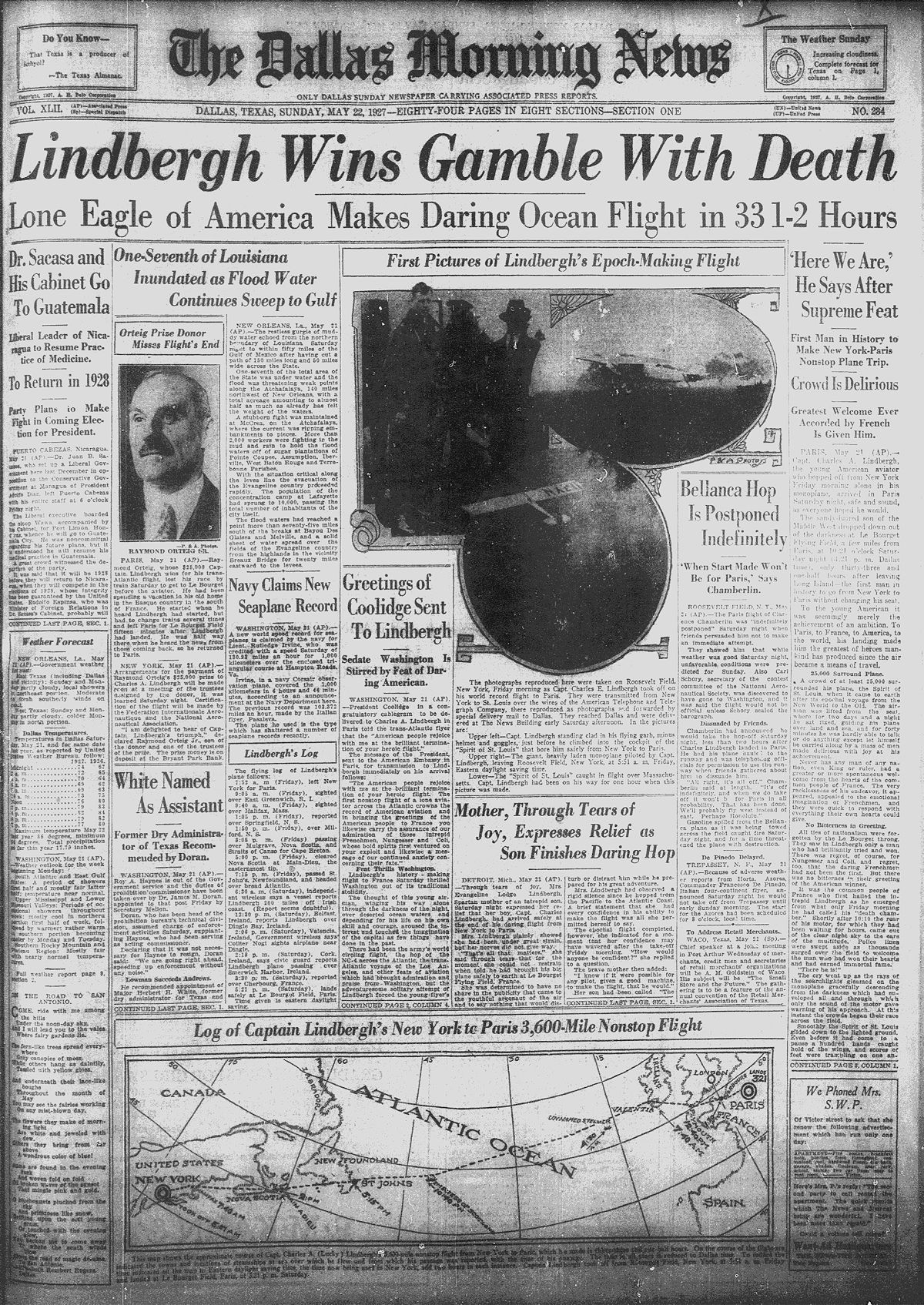

Thirty-three and a half hours and 3,500 miles later Lindbergh landed in Paris, the first person to fly across the Atlantic Ocean alone and nonstop.

Thirty-three and a half hours and 3,500 miles later Lindbergh landed in Paris, the first person to fly across the Atlantic Ocean alone and nonstop.

At the Paris airport a crowd of 100,000 watched him land. Despite the presence of soldiers with fixed bayonets, thousands rushed past barricades to the airplane, wanting to touch Lindbergh, to have a piece of his airplane as a souvenir. He was carried off the field on the shoulders of police officers. French President Gaston Doumergue awarded Lindbergh the nation’s highest honor: the Cross of Légion d’Honneur.

In America a burgeoning mass media—newspapers, radio, newsreels—made “Lucky Lindy” an instant cultural hero. New York City gave him the largest ticker-tape parade yet; President Coolidge awarded him the Distinguished Flying Cross. A dance was named after “Lindy” and his “hop” across the ocean. A Pullman sleeping car was named after him. Babies were named after him. Several countries would issue postage stamps honoring him.

Indeed Lindbergh’s flight captured the imagination of the public and increased interest in the potential of commercial aviation.

Lindbergh rested a few weeks and wrote his autobiography (he was twenty-five!) and then began another unprecedented flight: an aerial tour of America sponsored by the Daniel Guggenheim Fund for Promotion of Aeronautics.

On July 20 Lindbergh again took off in the Spirit of St. Louis from Long Island, this time to visit ninety-two cities in forty-eight states as he connected the dots across America.

Fort Worth would be one of those dots.

Lindbergh had become America’s superstar. He was the Beatles with an altimeter instead of an amplifier.

Every day for three months hundreds of newspapers printed a story daily about Lindbergh’s tour, if only a short paragraph reporting that he had progressed from dot D to dot E.

In each city he visited, parades and proclamations were de rigeur. Boys built models of the Spirit of St. Louis to win a contest to meet the great man. More than one hundred towns in west Texas sent their “fairest daughters” to Abilene to greet him when he landed there. The young women were called “Spirits” in honor of Lindbergh’s airplane. Companies gave away “Lindbergh calendars.” Stores sold Lindbergh pennants, flags, and automobile radiator cap flag-holders. On the eve of “Lindbergh Day” in Abilene, the mayor urged all residents to cut weeds on their premises and vacant lots and remove all trash. For those who did not live in one of the lucky Lucky Lindy cities, railroads offered reduced rates to the anointed cities.

Bookstores hawked copies of his autobiography. Music stores sold Victor phonograph recordings of the speech Lindbergh had made to the National Press Club in Washington and sheet music for “The Spirit of St. Louis March” song. Auto stores touted AC brand sparkplugs as the brand used by Lindy. Gas stations bragged that Lindbergh used Calumet motor oil in his airplane.

Lindbergh was pelted with gifts: medals, keys to cities, a silk parachute, model monoplanes made of sterling silver and diamonds. He was made an honorary member of organizations (United Daughters of the Confederacy, Scabbard and Blade military fraternity, International Union of Bricklayers, etc.). A Choctaw tribesman gave him the name “Tohbionssi Chitokaka” (“Greatest White Eagle”).

On the day of Lindbergh’s arrival in each city, businesses closed, clubs canceled scheduled meetings, schools dismissed students. People swarmed the local airport, sat on the hoods of cars, holding their breath to hear the faint drone of that Wright radial engine, squinting into the sky to catch the first glimpse of Lindbergh. Policemen and national guardsmen kept order. Newspapers urged readers not to “tear the Spirit of St. Louis apart for souvenirs.”

Sometimes as Lindbergh flew over a town but did not land there, he dropped a letter to that city thanking residents for their interest in his tour.

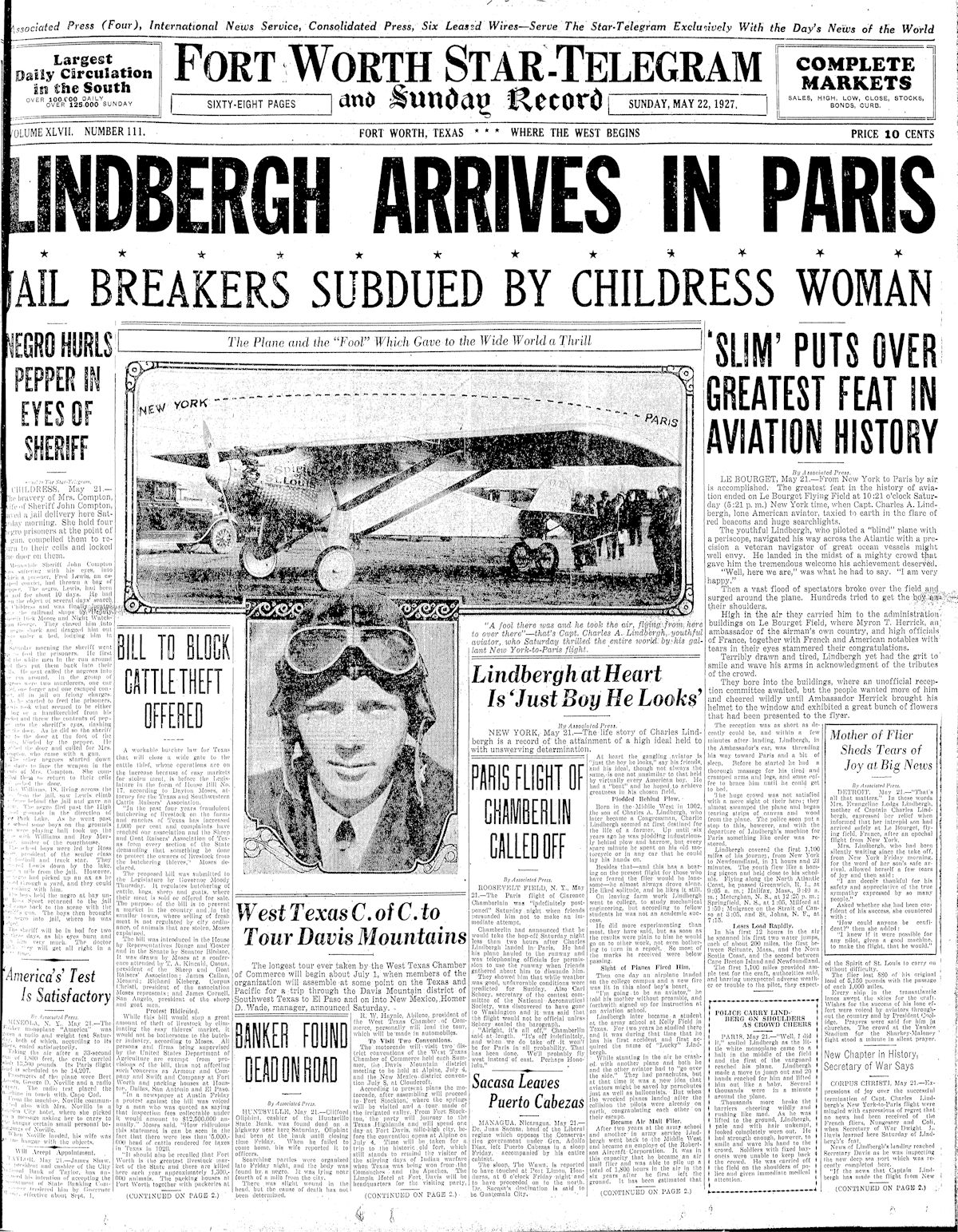

By September, flying from west to east, Lindbergh had reached Texas. Lindymania was rampant.

Lindbergh’s first stop in Texas was El Paso. The city presented Lindbergh with a sombrero and a serape. And what did Lindbergh eat for lunch in El Paso? The El Paso Times knew you’d ask: one club sandwich, one pimiento cheese sandwich, one order of shoestring potatoes, a dish of ice cream, a cup of coffee, and a glass of milk.

Lindbergh’s first stop in Texas was El Paso. The city presented Lindbergh with a sombrero and a serape. And what did Lindbergh eat for lunch in El Paso? The El Paso Times knew you’d ask: one club sandwich, one pimiento cheese sandwich, one order of shoestring potatoes, a dish of ice cream, a cup of coffee, and a glass of milk.

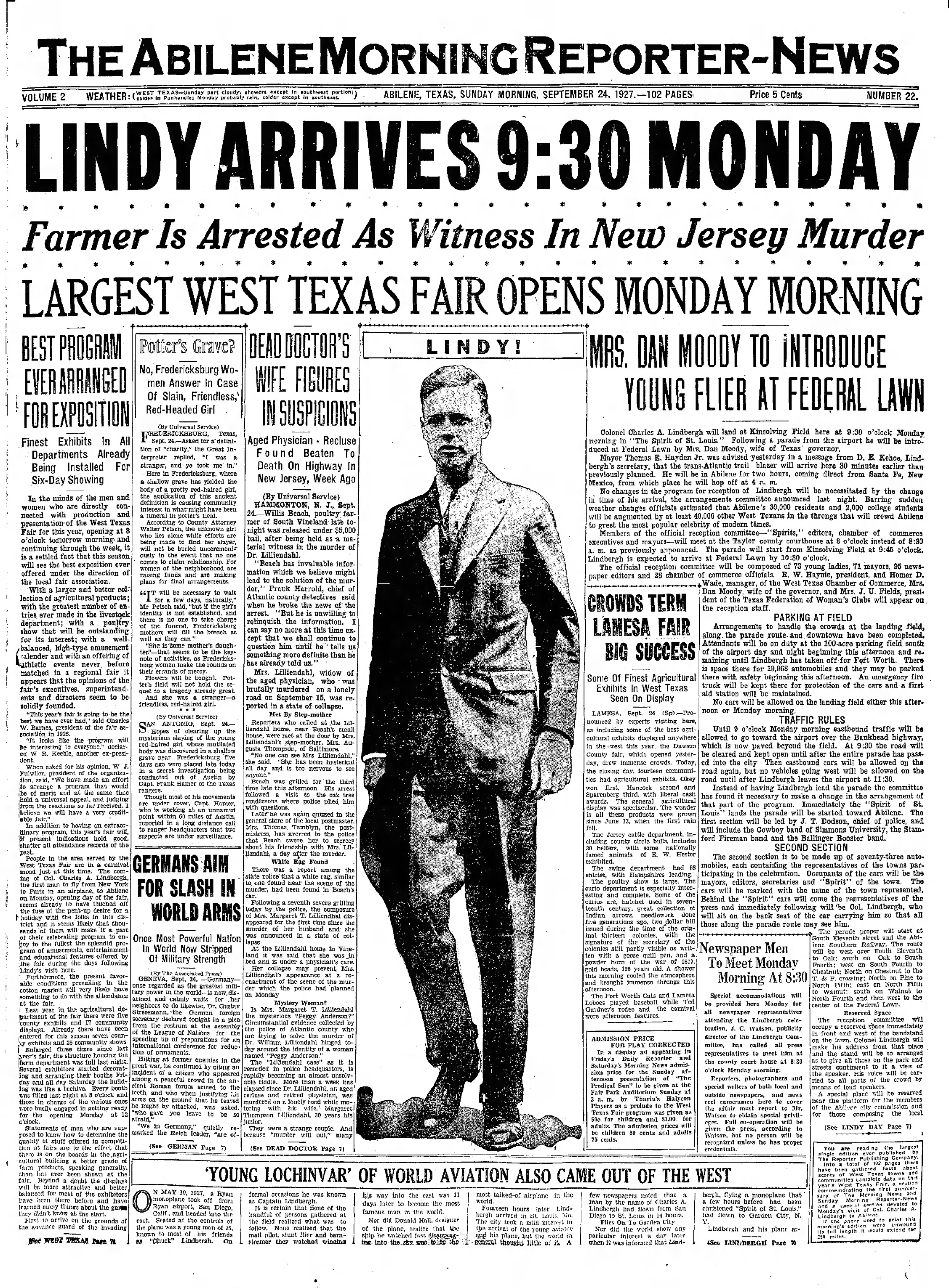

In Abilene about sixty thousand people greeted Lindbergh. The Abilene Morning Reporter-News noted that the September 24 edition of the Reporter-News, with 102 pages, was the largest ever printed.

In Abilene about sixty thousand people greeted Lindbergh. The Abilene Morning Reporter-News noted that the September 24 edition of the Reporter-News, with 102 pages, was the largest ever printed.

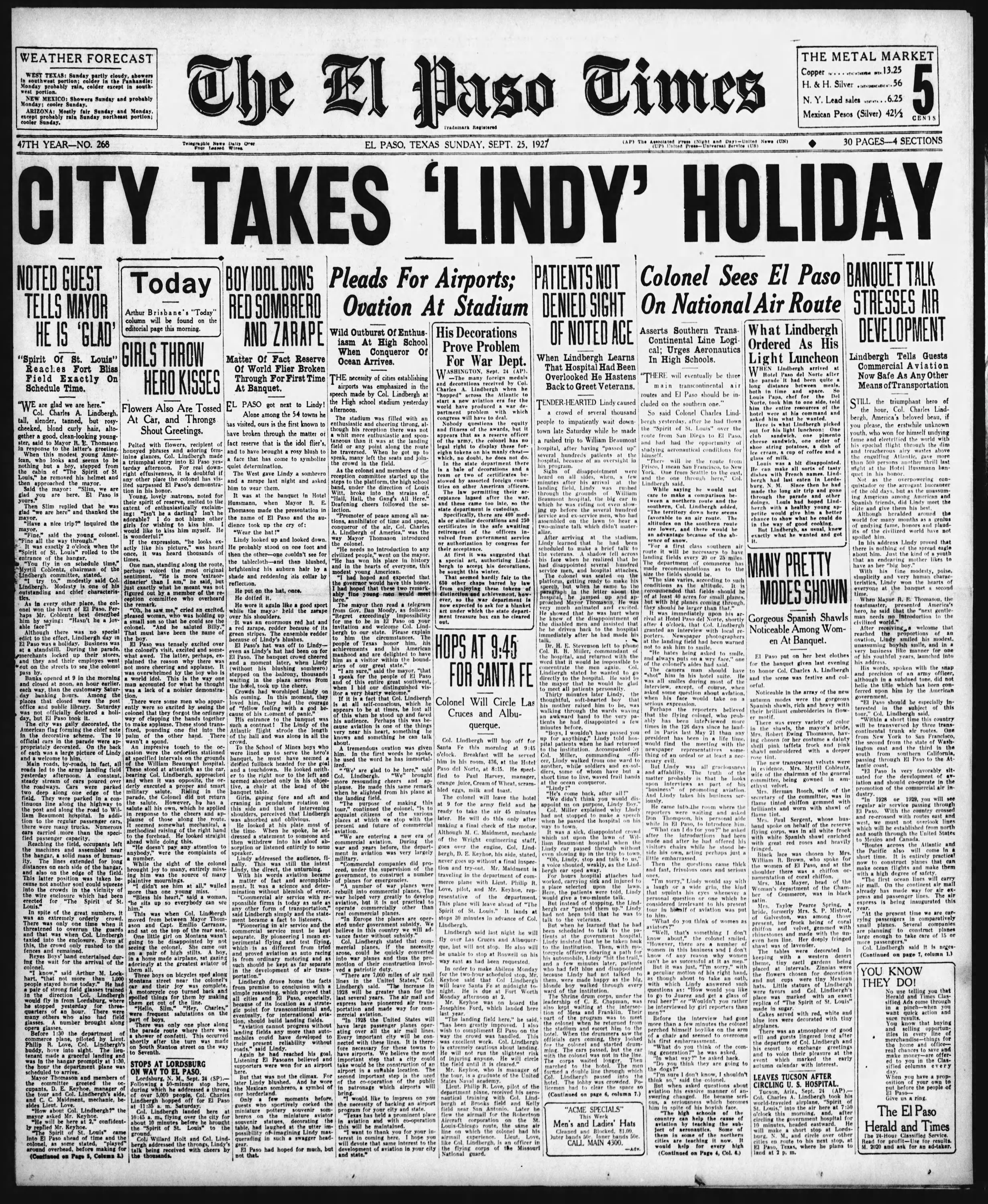

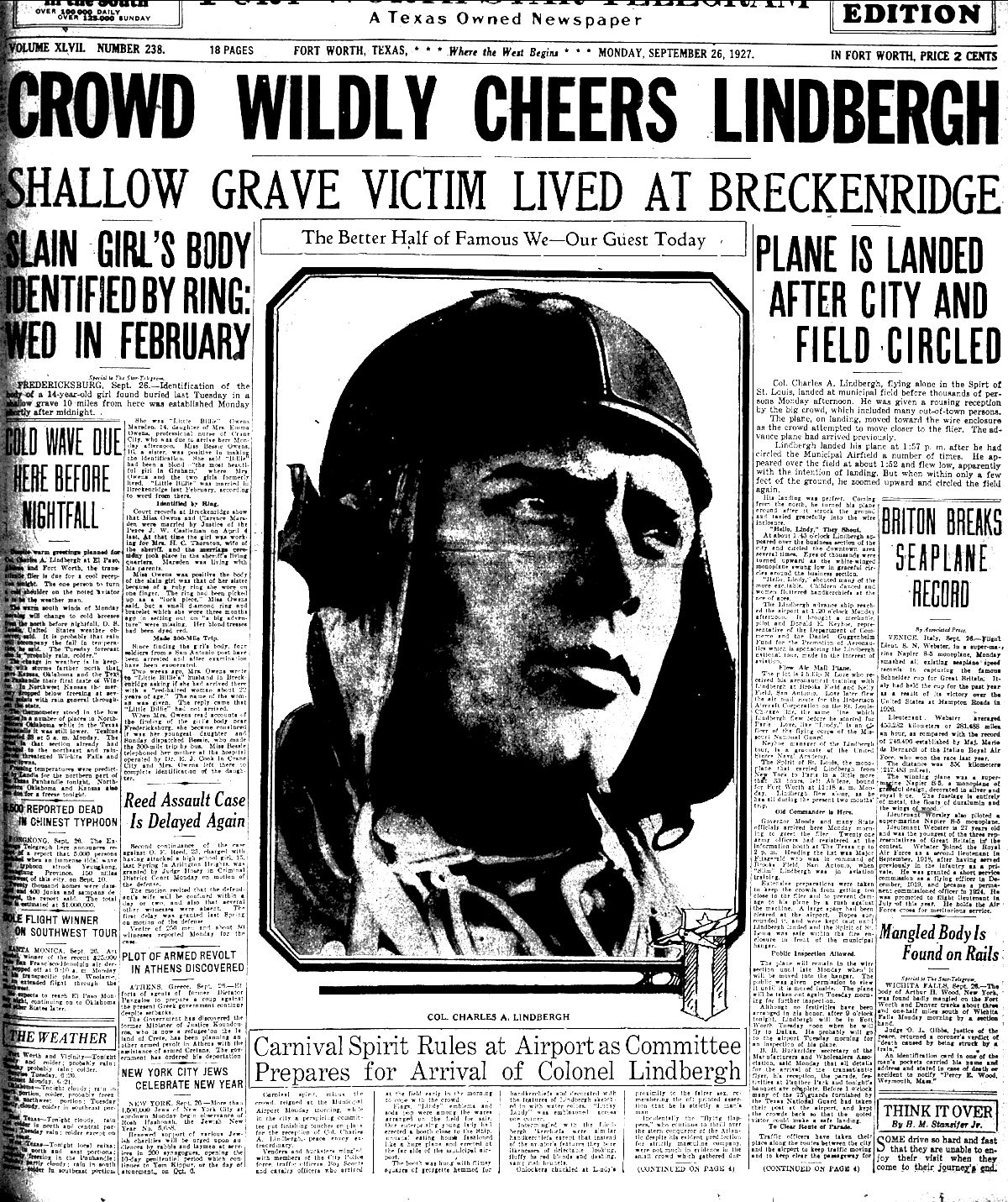

Then came September 26. Lindbergh took off from the Abilene airport and headed east. Fort Worth was the next dot to be connected. Lindbergh was not scheduled to land at Meacham Field until the afternoon. But on the night of September 25 some people had parked around the airport and sustained themselves through the night with sandwiches and Thermos bottles of coffee, like fans waiting in line overnight to buy tickets to a Beatles concert.

By noon thirty-five thousand people were in and around Meacham Field. Police officers controlled traffic; National Guard troops kept the crowd back along a roped-off area enclosing the runway and hangars.

Just how big was Charles Lindbergh in 1927? He was even bigger than the Dallas-Fort Worth rivalry: One of those thirty-five thousand people at Meacham Field was a Dallas Morning News reporter.

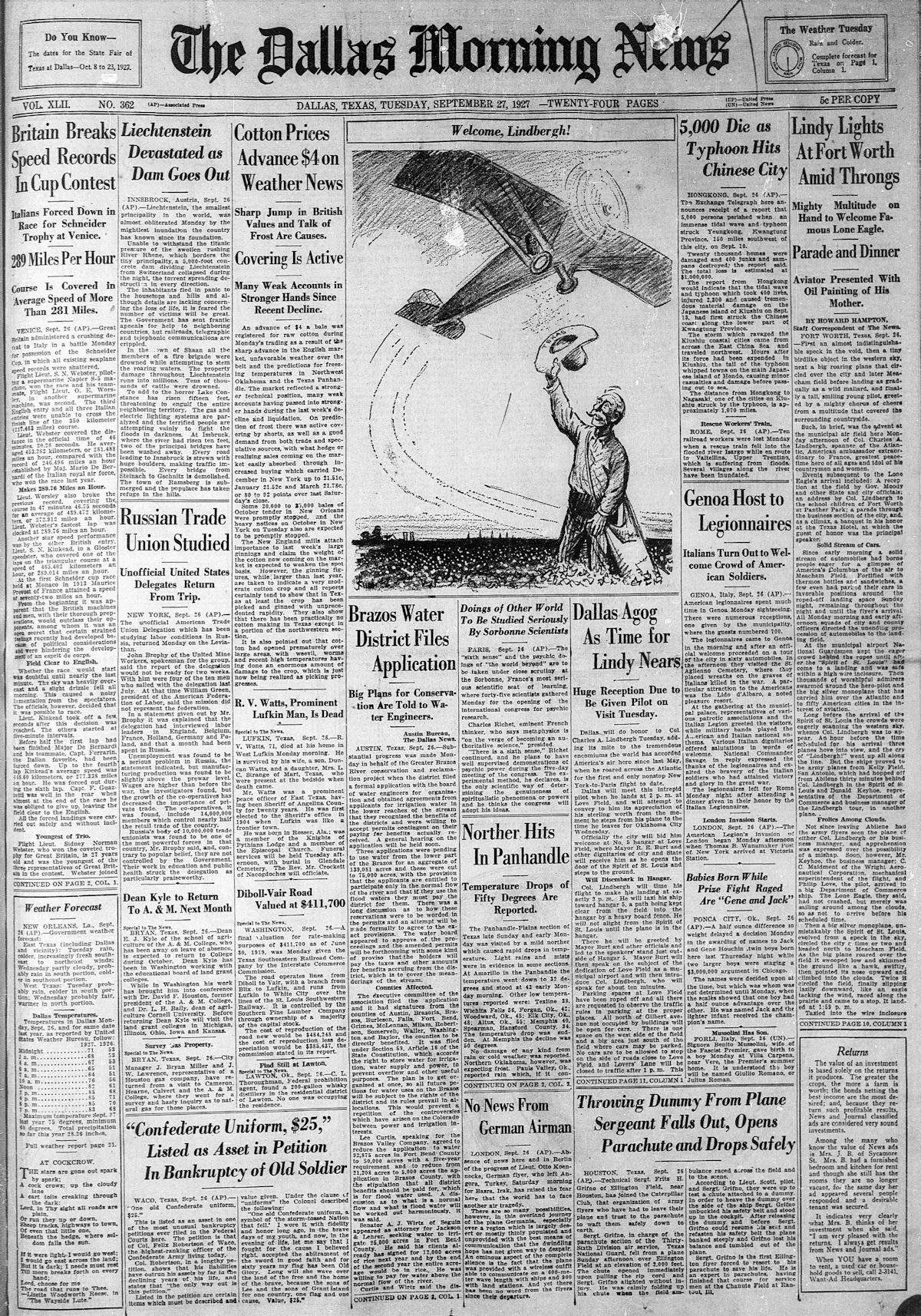

In fact, Lindbergh’s landing in Fort Worth was the lead story on page 1 of the Morning News. “Dallas Agog As Time for Lindy Nears,” read a smaller headline.

In fact, Lindbergh’s landing in Fort Worth was the lead story on page 1 of the Morning News. “Dallas Agog As Time for Lindy Nears,” read a smaller headline.

Each time an airplane appeared in the sky over north Fort Worth on September 26, the cry “Lindbergh!” went up from the crowd. After several false alarms, just before 2 p.m. the Spirit of St. Louis appeared from the west and circled the airfield twice before landing. Lindbergh was “greeted by a mighty chorus of cheers from a multitude that covered the surrounding countryside,” the Dallas Morning News wrote.

The Morning News referred to Lindbergh as “America’s Columbus of the air,” an “American Prince of Wales,” “the greatest peacetime hero of all ages and idol of his countrymen and women.”

At Meacham Field Lindbergh was greeted by Governor Dan Moody and other military, government, and civic leaders.

Cameras rolled for Pathe and Fox newsreels.

A band from the 144th Infantry Regiment played “Stars and Stripes Forever.”

Major W. S. Fitzgerald, commander of Brooks Field in San Antonio, flew in on a Curtiss biplane to congratulate Lindbergh. Fitzgerald had been Lindbergh’s flight instructor at Brooks Field three years earlier.

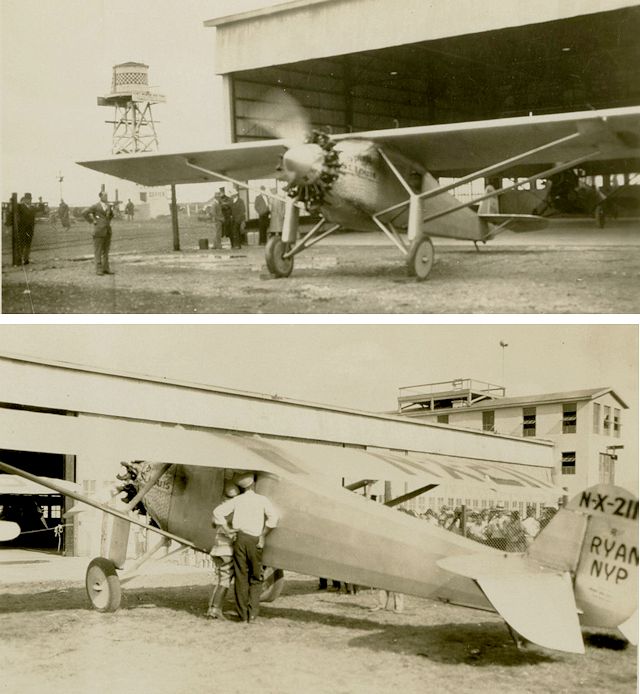

The Spirit of St. Louis at Meacham Field. (Photos from University of Texas at Dallas.)

The Spirit of St. Louis at Meacham Field. (Photos from University of Texas at Dallas.)

Lindbergh was then driven in a convoy of limousines to Panther Park (LaGrave Field) baseball stadium. Twenty thousand school children had the day off to pack the stadium. Little Zene Irwin presented Lindbergh with a bouquet on behalf of the students.

Then came a parade downtown.

For his overnight stay, Lindbergh was given the Presidential Suite at the Hotel Texas. He also was presented with an oil painting of his mother (“Spartan mother of an intrepid son” wrote one newspaper), who had “calmly” taught her chemistry class in Detroit as her son made his historic flight to Paris. Fort Worth civic leaders had commissioned the painting.

At a banquet in the hotel’s Crystal Ballroom that night Lindbergh addressed eight hundred people. Much of his speech in each town stressed the great potential—and safety—of commercial aviation. But he also described his trans-Atlantic flight. An excerpt from his Fort Worth speech:

“There’s one thing I want to get straight about this flight. They call me ‘Lucky,’ but luck isn’t enough. As a matter of fact I had what I regarded, and still regard, as the best existing plane to make the flight from New York to Paris. I had what I regarded as the best engine and I was equipped with what were in the circumstances the best possible instruments for making such efforts.

“That I landed with considerable gasoline left means that I had recalled the fact that so many flights had failed because of lack of fuel, and that was one mistake I avoided. All in all I couldn’t complain of the weather. It wasn’t what was predicted. It was worse in some places and better in others. In fact, it was so bad once that for a moment there came over me the temptation to turn back. But then I figured it was probably just as bad behind me as before me, so we [my ship and I] kept on toward Paris.

“We had been told we might expect good weather mostly during the whole of the way but we struck fog and rain over the coast, not far from the start. Actually, it was comparatively easy to get to Newfoundland, but real bad weather began just about dark, after leaving Newfoundland and continued till about four hours after daybreak. We hadn’t expected that at all and it sort of took us by surprise, morally and physically. That was when I began to think about turning back.

“Then sleet began, and as all aviators know, in a sleet storm one may be forced down in a very few minutes. It got worse and worse. There, above and below me, and on both sides, was that driving storm. I made several detours trying to get out of it, but in vain. I flew as low as 10 feet above the water and then mounted up to 10,000 feet. Along toward morning the storm eased off and I came down to a comparatively low level.

“The only real danger I had was at night. In the daytime I knew where I was going but in the evening and at night it was largely a matter of guesswork. However, my instruments were so good that I could never get more than 200 miles off my course and that was easy to correct as I had enough extra gasoline to take care of a number of such deviations.”

Of his landing in Paris Lindbergh said:

“That reception was the most dangerous part of the trip. Never in my life have I seen anything like that human sea. It isn’t clear to me yet just what happened. Before I knew it I had been hoisted out of the cockpit and one moment was on the shoulders of some men and the next moment on the ground. It seemed to be even more dangerous for my plane than for me. I saw one man tear away the switch and another took something out of the cockpit. Then when they started cutting pieces of cloth from the wings I struggled to get to the plane, but it was impossible.

“A brave man with good intentions tried to clear a way for me with a club. Swinging the club back, he caught me on the head.”

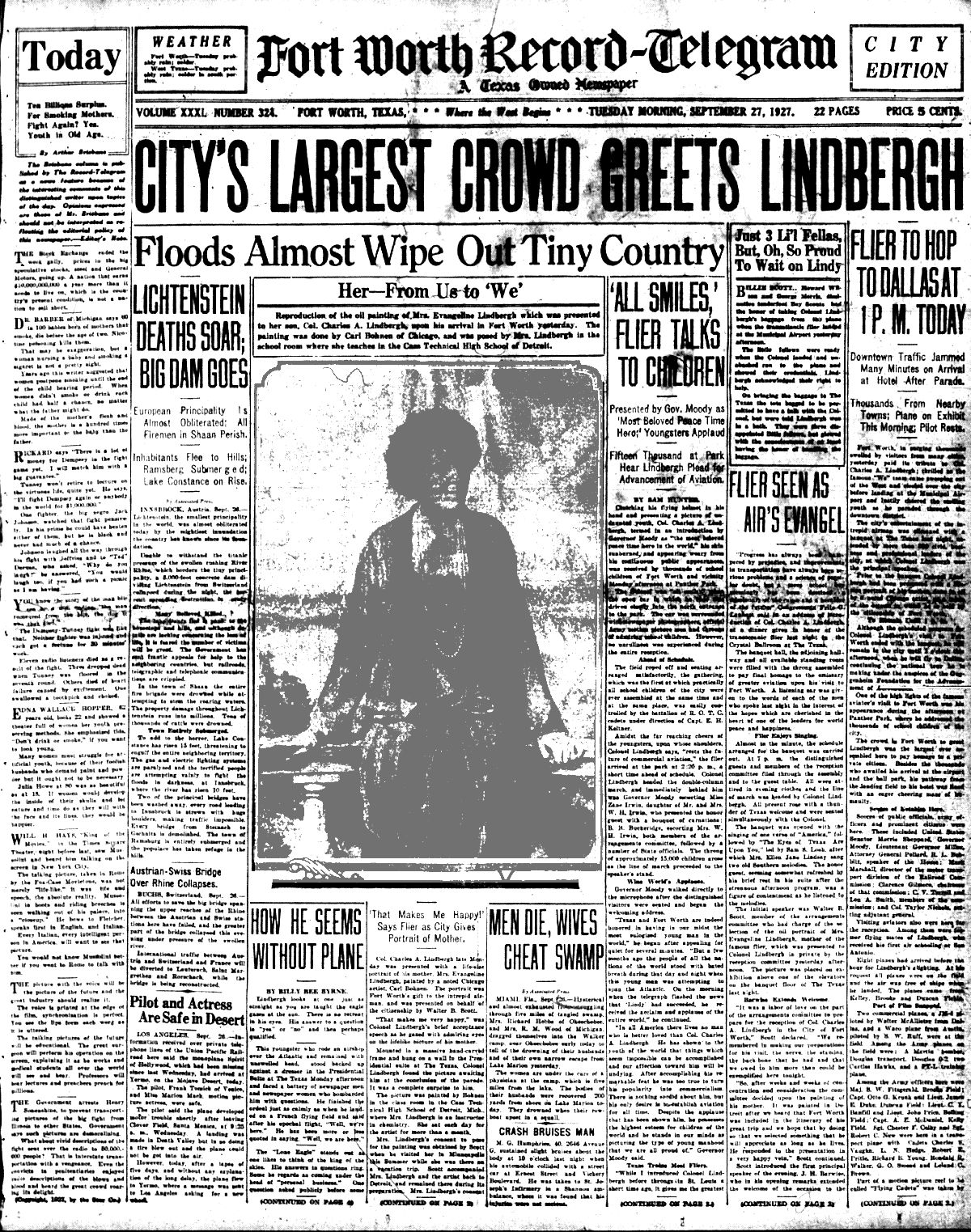

Fort Worth’s three newspapers devoted their front pages to Lindbergh’s visit here:

The Star-Telegram reported that when Lindbergh touched down at Meacham Field, “children danced and women fluttered handkerchiefs at the ace of aces.”

The Star-Telegram reported that when Lindbergh touched down at Meacham Field, “children danced and women fluttered handkerchiefs at the ace of aces.”

The Press reported that accompanying the convoy of limousines from the airport to Panther Park were a National Guard band, fifty mounted cowboys, and floats from TWC, TCU, and the Battercake Flats area of north Fort Worth.

The Press reported that accompanying the convoy of limousines from the airport to Panther Park were a National Guard band, fifty mounted cowboys, and floats from TWC, TCU, and the Battercake Flats area of north Fort Worth.

The Record-Telegram reported that the crowd at the airport was the largest ever to greet a private citizen in Fort Worth and that the rally at Panther Park was “the first at which practically all school children of the city were ever assembled at the same time and at the same place.” The Record-Telegram front page featured the life-sized portrait of Lindbergh’s mother.

The Record-Telegram reported that the crowd at the airport was the largest ever to greet a private citizen in Fort Worth and that the rally at Panther Park was “the first at which practically all school children of the city were ever assembled at the same time and at the same place.” The Record-Telegram front page featured the life-sized portrait of Lindbergh’s mother.

The next morning, September 27, Lindbergh took off from Meacham Field, circled downtown, dipped his wings in farewell, and headed to Dallas.

The Morning News reported that ten thousand people greeted Lindbergh at Love Field in Dallas and that along the route of his motorcade to downtown the turnout was “estimated to be close on 100,000 people.”

The Morning News reported that ten thousand people greeted Lindbergh at Love Field in Dallas and that along the route of his motorcade to downtown the turnout was “estimated to be close on 100,000 people.”

On September 28 Lindbergh left Texas air space, flying from Dallas toward Oklahoma City to continue his tour. As he passed over Denton’s College of Industrial Arts with its female student body he circled the campus—six times!—and dropped an autographed letter.

John, Paul, George, and Ringo could not have inspired more swoons.

By the time Lindbergh ended his three-month tour, landing in New York on October 23, he had ridden 1,290 miles in parades, given 147 speeches, and flown 22,000 miles—almost the circumference of the Earth.

Jim, What a great article and the newspaper coverage was extraordinary. I hope all is well at FWAM. Keep up the good work and I hope to visit later in the fall.

The No. 1 BFTS Museum just took delivery of a fourth Link trainer we hope to restore to operational condition.

Cheers, Rudy

Thank you, Rudy.