They are the forgotten players of an unforgettable season.

You won’t find them on baseball cards or in Cooperstown. They didn’t earn big salaries or sign lucrative endorsement contracts.

They just played good baseball.

So what if the good baseball they played was for a minor league team: the Fort Worth Panthers? In 1920 no city west of St. Louis had a major league team. Minor league baseball was composed of several leagues ranked by playing level. Class A leagues played at a higher level than Class B leagues, Class B leagues played at a higher level than Class C leagues, etc.

The Panthers were in the Class B Texas League. There were no Class A teams in Texas.

But fans didn’t care about hierarchy. They cared about their home team.

And in 1920 Panthers fans, with the Star-Telegram as head cheerleader, were ready to root, root, root for the home team.

The Star-Telegram covered a wide spectrum of baseball, from the major leagues to local church leagues. But its pet team, of course, was the Panthers.

The Star-Telegram covered a wide spectrum of baseball, from the major leagues to local church leagues. But its pet team, of course, was the Panthers.

As members of the team arrived in Fort Worth for spring training in 1920 they saw familiar faces: The 1920 team was essentially the 1919 team.

And that was good.

The pitching staff was seasoned and balanced, with two lefties and four righties, two of whom were spitballers. The spitball was legal in the Texas League in 1920.

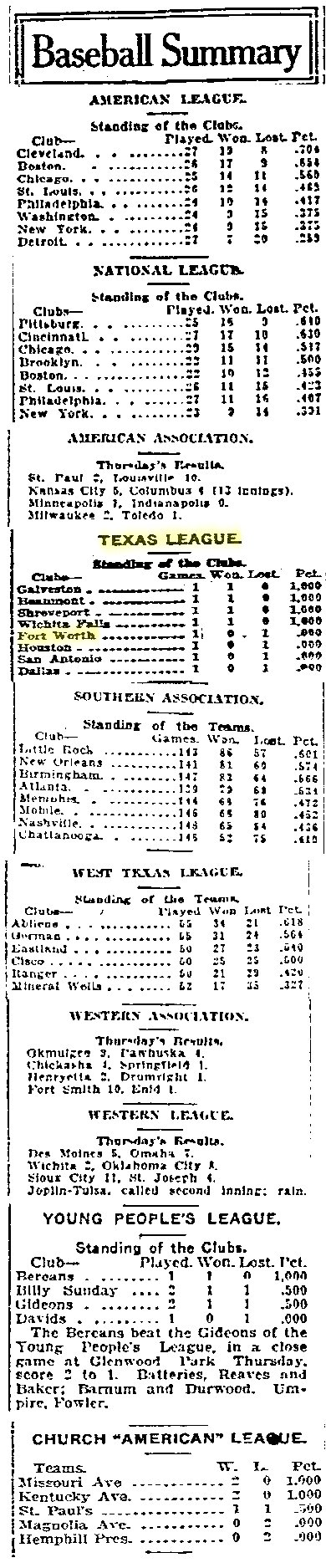

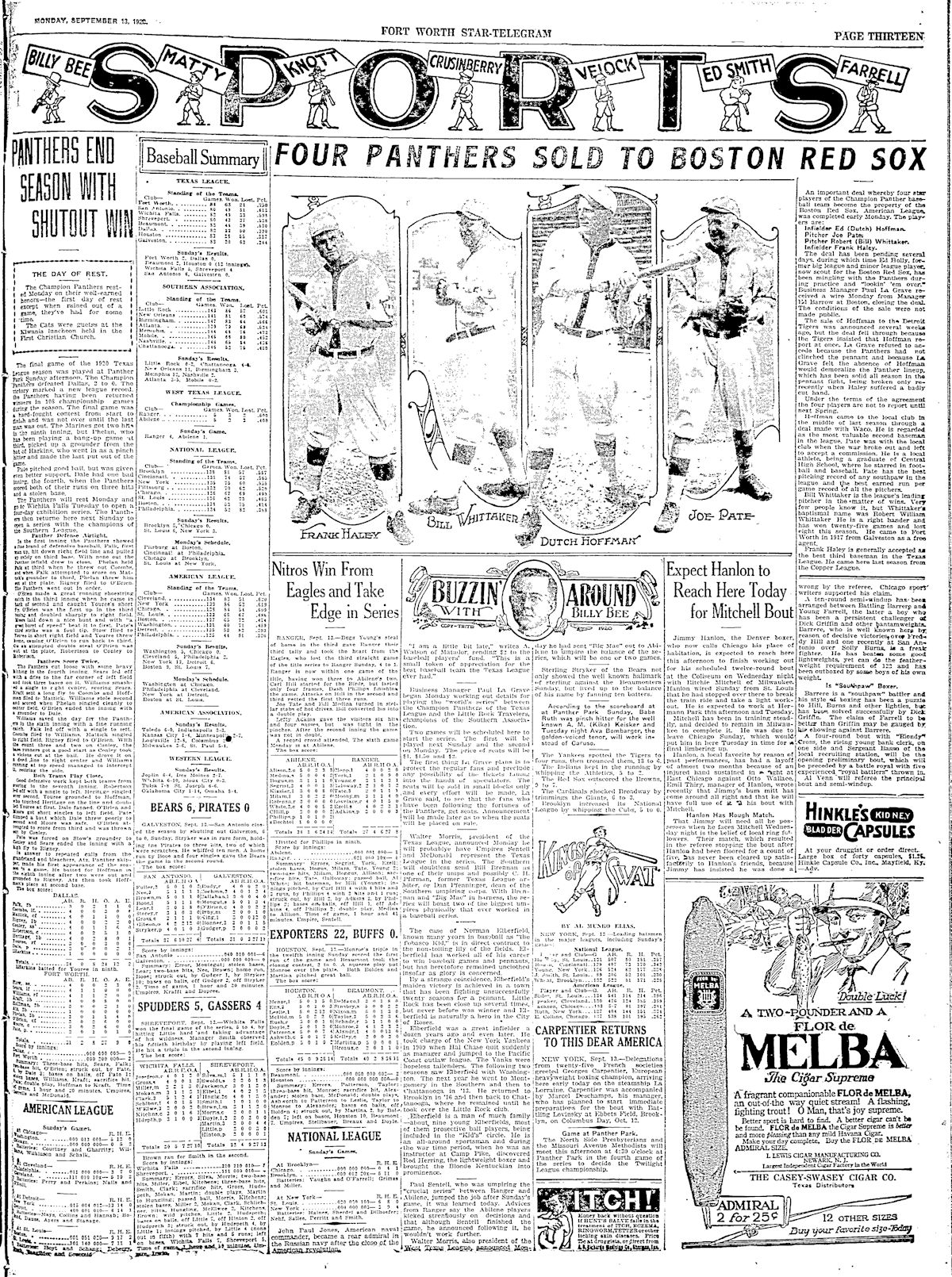

The 1920 team had four stars in third baseman Frank Haley, pitcher Bad Eye Whittaker, second baseman Dutch Hoffman, and pitcher Joe Pate.

The 1920 team had four stars in third baseman Frank Haley, pitcher Bad Eye Whittaker, second baseman Dutch Hoffman, and pitcher Joe Pate.

A few Panthers, such as manager Jake Atz, forty-one, had enjoyed their “cuppa coffee” in “the Bigs” and soon returned to the minors. Atz had been a plumber and vaudeville comedian before discovering that his genius lay in baseball—more as a manager than a player. Atz was popular with the fans and the Star-Telegram. Informal names for the Panthers were “Atzmen” and “Atz Cats.”

A few Panthers, such as manager Jake Atz, forty-one, had enjoyed their “cuppa coffee” in “the Bigs” and soon returned to the minors. Atz had been a plumber and vaudeville comedian before discovering that his genius lay in baseball—more as a manager than a player. Atz was popular with the fans and the Star-Telegram. Informal names for the Panthers were “Atzmen” and “Atz Cats.”

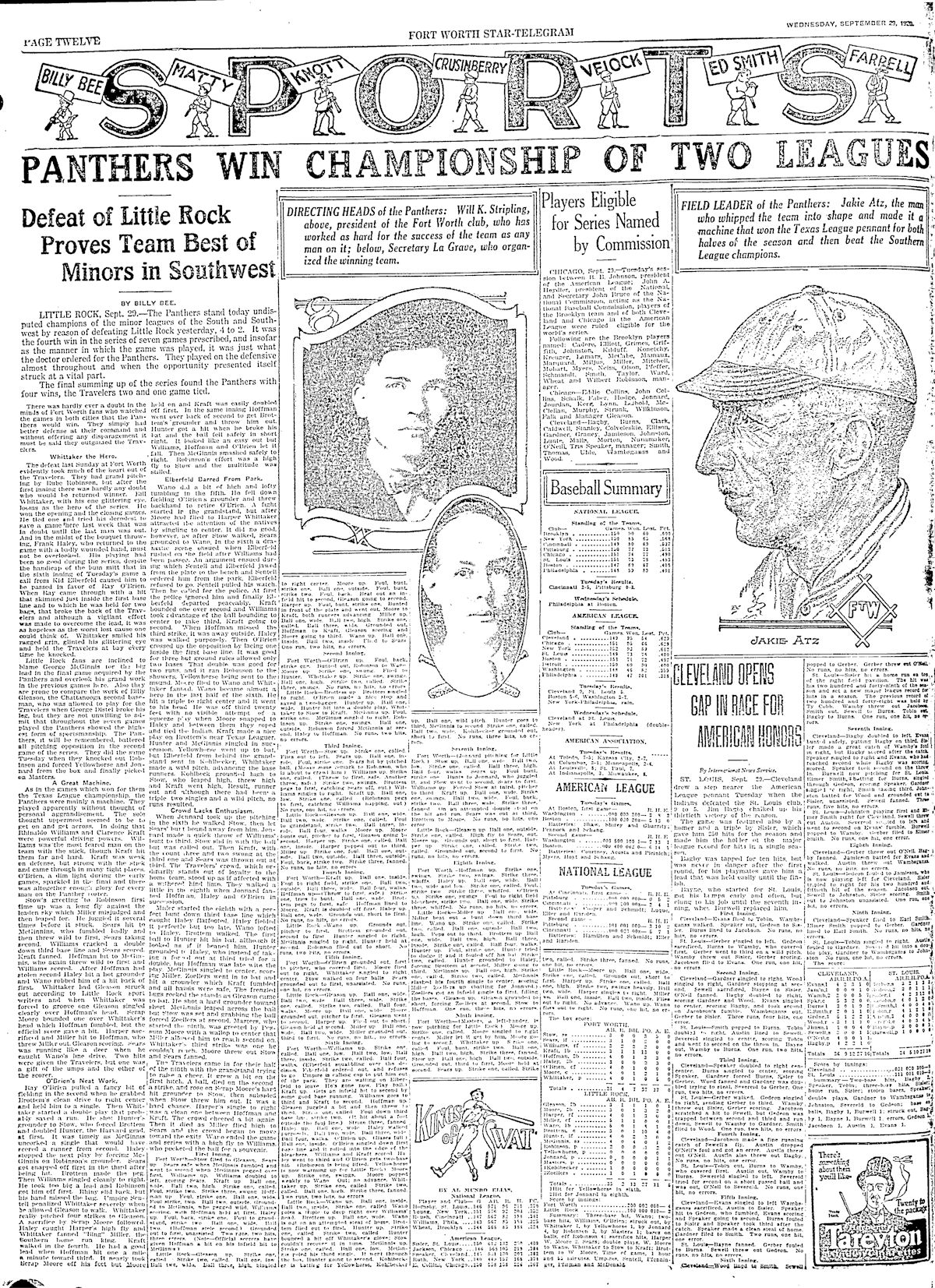

On the business side of the lineup, the president of the team was William Kingsberry Stripling (top photo), son of the department store founder. Business manager was Paul LaGrave (bottom photo). LaGrave had been a minor league infielder before moving from a base to a desk in the Panthers head office.

On the business side of the lineup, the president of the team was William Kingsberry Stripling (top photo), son of the department store founder. Business manager was Paul LaGrave (bottom photo). LaGrave had been a minor league infielder before moving from a base to a desk in the Panthers head office.

LaGrave helped Atz build a solid and stable team by recruiting players who were content with the pay, play, and (lack of) prestige of the minor leagues. (The average salary in the Texas League in 1920 was $165 [$2,000 today] a month.)

Most of the 1920 Panthers were in their mid- to late twenties. Few rookies. They had played on teams with names such as the Flint Vehicles, Wichita Falls Spudders, Cleveland Spiders, South Bend Benders, Albany Nuts, Terre Haute Tots, Atlanta Crackers, Shreveport Gassers, Mt. Sterling Orphans, Dubuque Dubs, Charles City Tractorites.

Baseball loves nicknames, and the Panthers of 1920 had plenty: Dutch, Possum, Bad Eye, Buggs, Buzzer, Big Boy, Ziggy, Rhiny, and, of course, the obligatory Lefty.

Dutch and Possum and Bad Eye et al. were coming off a good 1919 season. In fact, in 1919’s two-half season the Panthers had won the second half but had lost in the postseason playoffs to first-half winner Shreveport.

Oh, well. Get ’em next time.

Come spring of 1920 “next time” was just a few exhibition games away.

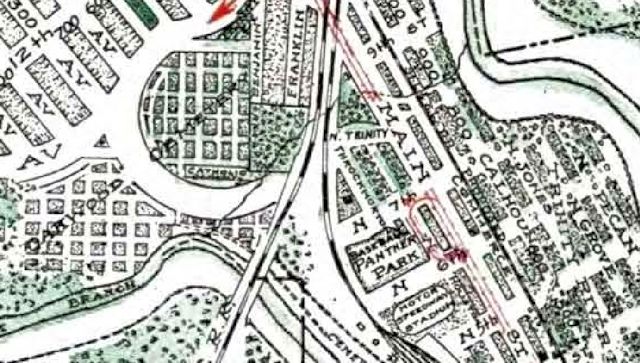

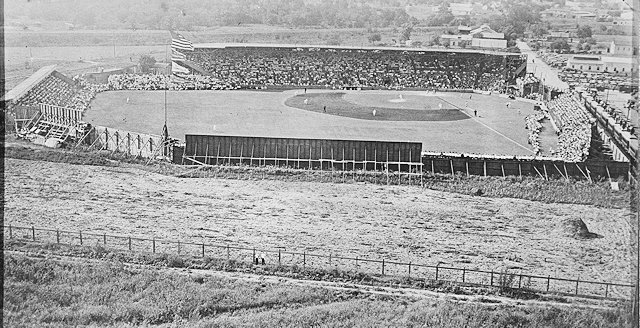

The Panthers’ lair was Panther Park, located four blocks west of today’s (abandoned) LaGrave Field. (Photo from Jack White Photograph Collection, University of Texas at Arlington Libraries.)

Panther Park had been built in 1911 as Morris Park, named for Walter Morris, president of the league and president of the Panthers. It was renamed “Panther Park” in 1914.

The yellow rectangle shows the location of Panther Park between North 6th and 7th streets and between North Houston Street and the Cotton Belt railroad track. The curve of the track can still be seen to the right of the rectangle. Capacity of the park was 4,600.

Neither players nor fans knew it as Panther Park began to fill for the first exhibition game in the spring of 1920, but the Panthers that season would be playing for the biggest stakes in the team’s thirty-two-year history. And the summer of 1920 would be glorious, the sweet spot in time for the Fort Worth Panthers.

But not right off the bat.

But not right off the bat.

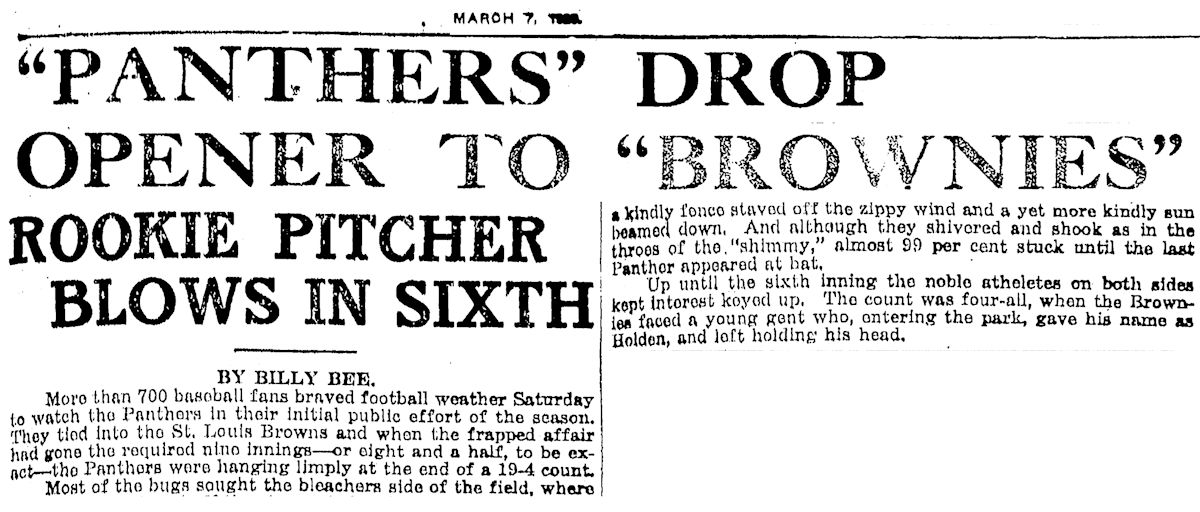

In weather better suited to football, on March 6 the Panthers lost their first exhibition game of 1920 19-4 to the St. Louis Browns.

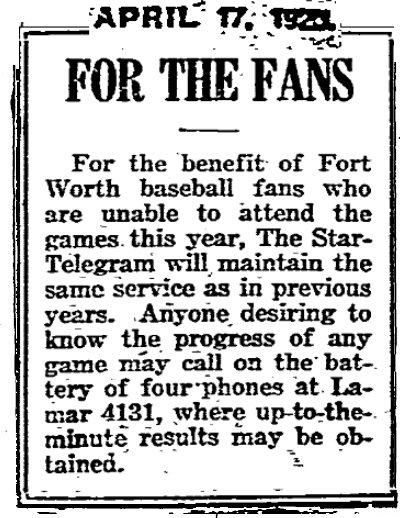

Fast-forward five weeks to opening day. Remember: There was no radio in 1920. Daily newspapers provided sports scores but only hours after a game. Amon Carter and the Star-Telegram realized that Panthers fans wanted scores on demand. So, as the season began the Star-Telegram provided four telephone operators to give scores to callers.

Fast-forward five weeks to opening day. Remember: There was no radio in 1920. Daily newspapers provided sports scores but only hours after a game. Amon Carter and the Star-Telegram realized that Panthers fans wanted scores on demand. So, as the season began the Star-Telegram provided four telephone operators to give scores to callers.

On April 16 the Panthers opened the season against their 1919 playoff nemesis, Shreveport, at Panther Park. Spitballer Paul Wachtel pitched for the Panthers.

On April 16 the Panthers opened the season against their 1919 playoff nemesis, Shreveport, at Panther Park. Spitballer Paul Wachtel pitched for the Panthers.

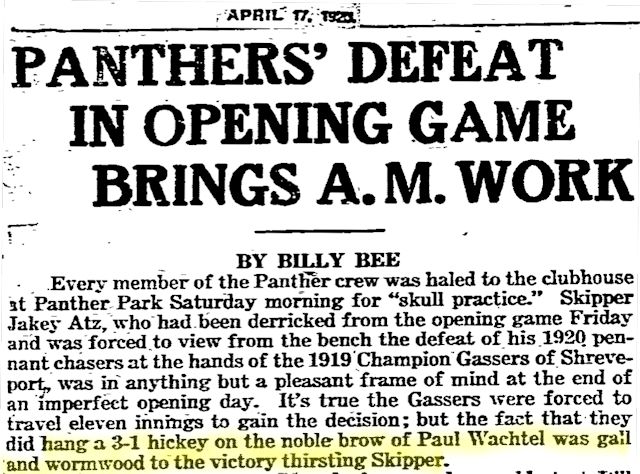

In the seventh inning the Panthers were behind 1-0. Perhaps manager Atz wanted to set a combative example for his players. Atz protested a called strike by the home plate umpire so vehemently that the umpire summoned a police officer to escort Atz off the field. The officer sat beside Atz on the dugout bench the rest of the game.

Atz’s feisty example notwithstanding, the Panthers lost game 1 of the season 3-1 in eleven innings. Or, as Star-Telegram sportswriter Billy Bee wrote, “the fact that they [the Shreveport Gassers] did hang a 3-1 hickey [loss] on the noble brow of Wachtel was gall and wormwood to the victory thirsting Skipper.”

Mercy!

The Star-Telegram assigned “little girl reporter” Mae Biddison (as in the South Side street) Benson to provide the non-fan perspective on opening day. She commented on the ejection of manager Atz by the umpire, writing, “I hope they made up afterward.”

The Star-Telegram assigned “little girl reporter” Mae Biddison (as in the South Side street) Benson to provide the non-fan perspective on opening day. She commented on the ejection of manager Atz by the umpire, writing, “I hope they made up afterward.”

After game 1 the Panthers quickly found their stride, winning three of four from the Dallas Marines to improve their record to 5-3 after eight games, good enough for third place.

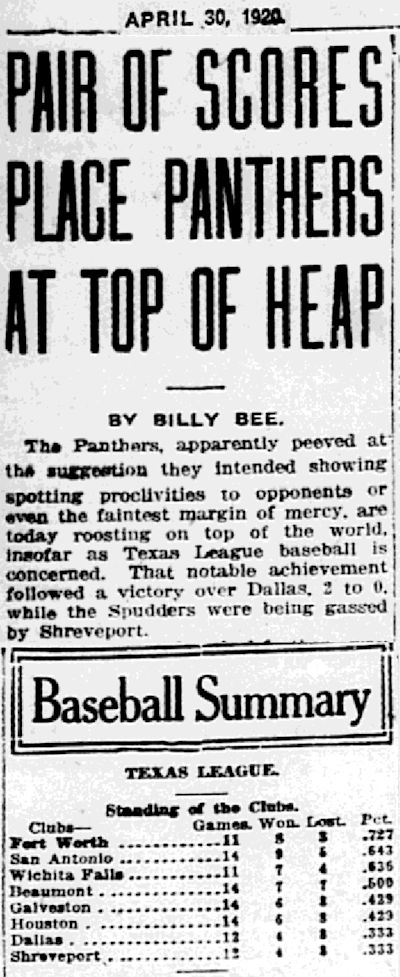

By April 30, with yet another win over Dallas and a loss by San Antonio, the Panthers had moved past San Antonio into first place.

By April 30, with yet another win over Dallas and a loss by San Antonio, the Panthers had moved past San Antonio into first place.

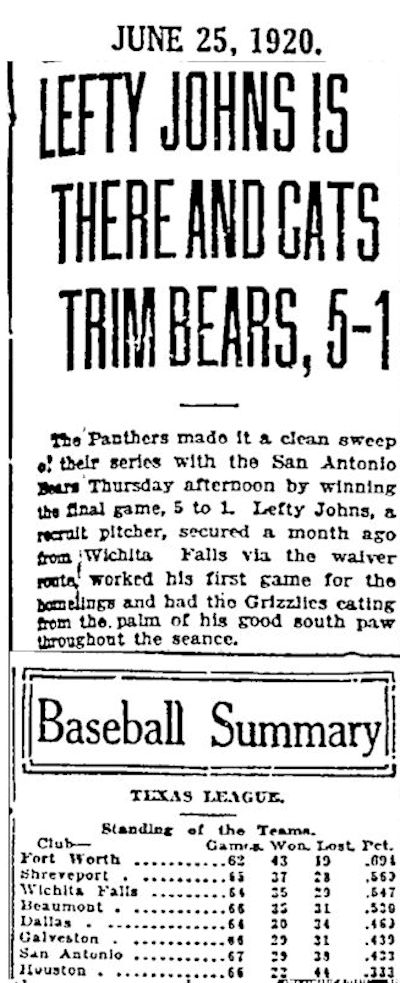

Fast-forward to June 26. Pitcher Lefty Johns, newly acquired from Wichita Falls, won as the Panthers completed a sweep of their series against San Antonio.

Fast-forward to June 26. Pitcher Lefty Johns, newly acquired from Wichita Falls, won as the Panthers completed a sweep of their series against San Antonio.

Roughly halfway through the season, the Panthers’ record was now 43-19—eight and a half games ahead of second-place Shreveport.

Panthers second baseman Dutch Hoffman was hitting .348, best in the league, and had hit seven homers so far. The Star-Telegram proclaimed him the Babe Ruth of the Texas League. (Ruth at that point had twenty-two homers on the way to fifty-four.)

Every Panthers pitcher had a winning record by June 26. Bad Eye Whittaker led the league in wins with twelve.

The Panthers were roaring.

But wait!

But wait!

That same day Texas League officials pressed the “reset” button: With the Panthers so far ahead, to maintain fan interest the season, again would be split into halves. The Panthers were declared the winner of the first half. Now the eight teams would start over 0-0. If the Panthers won the second half of the season, they would be the champions of the entire season. But if a team other than the Panthers won the second half, that team and the Panthers would meet in a playoff for the 1920 title.

Not to worry: The Panthers would be even more dominant in the second half.

The Panthers got off to a strong start in the second half and were 7-2 and in first place by July 3. They would be out of first place for only a few games in mid-July.

The Panthers got off to a strong start in the second half and were 7-2 and in first place by July 3. They would be out of first place for only a few games in mid-July.

Fast-forward to August 4. Panthers fans read sweet and sour headlines. The Panthers had just completed a twenty-four-game road trip in which they went 18-6, including fourteen wins in a row.

Fast-forward to August 4. Panthers fans read sweet and sour headlines. The Panthers had just completed a twenty-four-game road trip in which they went 18-6, including fourteen wins in a row.

But star second baseman Dutch Hoffman had been sold to the Detroit Tigers. Ah, but the Tigers wanted Hoffman to come up right away to help with their pennant race, and the Panthers wanted him to stay in Fort Worth to help with their pennant race. So, the deal fell through.

Whew.

With a six-game lead over second-place San Antonio, the Panthers were sure to win the second half of the season (and their first Texas League pennant since 1905), thus ensuring that there would be no playoff in 1920, right?

Wrong.

Because in early September Paul LaGrave and Texas League president Walter Morris pulled a cat out of a hat: They challenged the Southern Association to an interleague postseason series: The winner of the Class B Texas League would play a best-of-seven series against the winner of the Class A Southern Association, which would be the Little Rock Travelers.

Because in early September Paul LaGrave and Texas League president Walter Morris pulled a cat out of a hat: They challenged the Southern Association to an interleague postseason series: The winner of the Class B Texas League would play a best-of-seven series against the winner of the Class A Southern Association, which would be the Little Rock Travelers.

The winner of this series would be the champion of the southern minor leagues.

Remember: A Class B team should be outmatched by a Class A team.

Imagine the Bible’s David (Class B) on the mound, using his sling to pitch to Goliath (Class A) at the plate.

Paul LaGrave was well aware of how that matchup turned out.

On September 13 Panthers fans again read sweet and sour headlines:

On September 13 Panthers fans again read sweet and sour headlines:

The Panthers indeed had won the second half of the season, this time by twelve games with a 63-21 record. Their combined record for the two-half season was 108-40 (.730), the most wins in Texas League history up to that time.

The downside of having a winning season is that major league teams come to town with suitcases full of cash to buy the players who made that winning season possible. Four Panthers stars—Dutch Hoffman, Frank Haley, Joe Pate, and Bill Whittaker—had been sold to Boston.

The upside of the deal was that the four would be allowed to play in the interleague series against Little Rock. But could LaGrave and Atz find adequate replacements for the four lost stars for the 1921 season?

Dutch Hoffman was considered to be the best second baseman in the league, Frank Haley the best third baseman. Joe Pate and Bill Whittaker had won fifty games between them in 1920.

(Cuppa coffee spoiler: All four would be back in Panthers uniforms come spring 1921.)

So, how did the Panthers win both halves of the 1920 season with such dominance?

In a word, pitching.

Four pitchers—Pate, Wachtel, Whittaker, and Robertson—won 96 of the team’s 108 wins.

Remember complete games? In 1920 Panthers pitchers finished what they started: 126 complete games. Wachtel (26-10) and Pate (26-8) tied for the league lead in wins.

Pate also led in earned run average (1.71) and shutouts (9) and tied for second in complete games (31 out of 34 started).

Whittaker (24-6, 2.25) led in winning percentage (.800) and finished third in wins.

On defense the Panthers were second in fielding (.970) and first in assists (2,033).

On offense, despite their overall success, the Panthers did not lead the league in any batting category.

Dutch Hoffman was the Panthers’ only .300 hitter (.322), fifth in the league. The Panthers as a team batted .257.

One other element of the Panthers’ 1920 season catches the eye of today’s baseball fan: simplicity.

Only nineteen players appeared in a Panther uniform that season, and that includes manager Atz, who played second base in the last game of the regular season.

Atz seldom changed his lineup unless forced to by an injury. No platooning.

In 100 of 148 games in 1920 the team fielded the minimum nine players!

And now the Panthers would take their impressive regular season stats into an unprecedented interleague postseason series. Win it, and the Panthers would be the dukes of Dixie.

The best-of-seven series would alternate between the Fort Worth and Little Rock parks, beginning with two games in Fort Worth, then three games in Little Rock, then one game in Fort Worth and a seventh game in Little Rock if necessary.

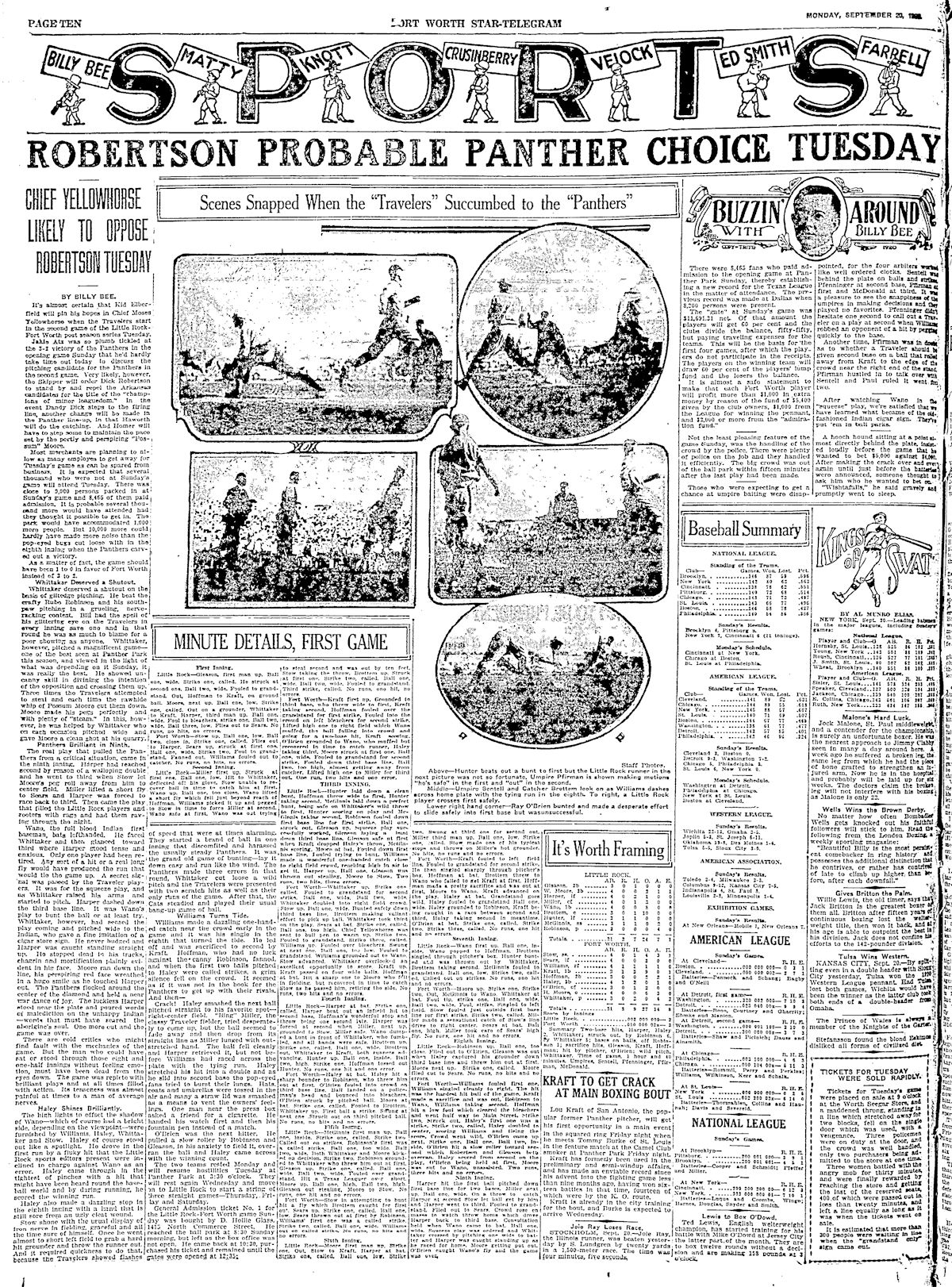

To accommodate fans of the Fort Worth home team, temporary outfield bleachers were added to Panther Park for the series. Many employers around town let workers have the day off to attend game 1. The first ticket for the game was bought by a fan who arrived at the ticket office at 5:30 a.m.—five hours before the office opened.

To accommodate fans of the Fort Worth home team, temporary outfield bleachers were added to Panther Park for the series. Many employers around town let workers have the day off to attend game 1. The first ticket for the game was bought by a fan who arrived at the ticket office at 5:30 a.m.—five hours before the office opened.

Game 1 was close, but the Panthers battery of pitcher Bad Eye Whittaker and catcher Possum Moore seemed to have a psychic edge: They conspired on three pitchouts to throw out Little Rock baserunners attempting to steal and a fourth who was attempting to steal home on a suicide squeeze play.

Score: Class B Panthers 3, Class A Travelers 2

Attendance at Panther Park set a Texas League record: 8,455.

Star-Telegram sportswriter Billy Bee wrote of the fans: “But 10,000 more could hardly have made more noise than the pop-eyed bugs cut loose with in the eighth inning when the Panthers carved out a victory.”

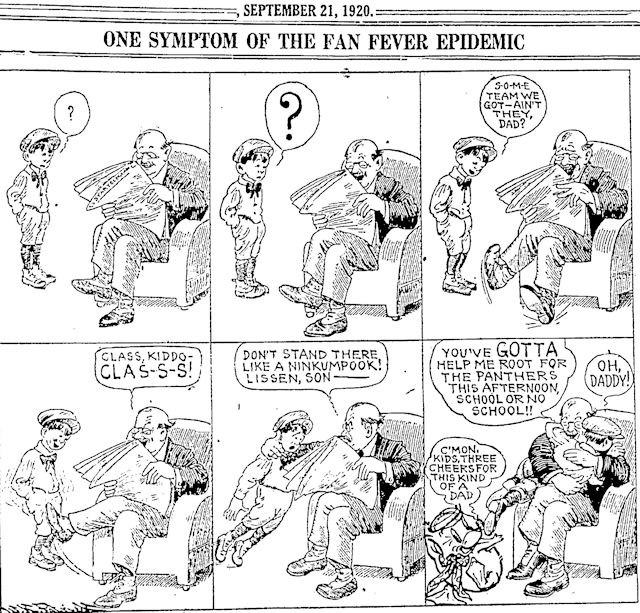

A page 1 cartoon in the Star-Telegram the next day hints that for some Fort Worth school students the three Rs temporarily were runner, reliever, and rhubarb.

A page 1 cartoon in the Star-Telegram the next day hints that for some Fort Worth school students the three Rs temporarily were runner, reliever, and rhubarb.

The Texas League allowed spitballs, the Southern Association did not. Thus, Panthers spitballers Paul Wachtel and Dick Robertson could salivate to their heart’s content in the games in Panther Park but not in Little Rock.

The Texas League allowed spitballs, the Southern Association did not. Thus, Panthers spitballers Paul Wachtel and Dick Robertson could salivate to their heart’s content in the games in Panther Park but not in Little Rock.

Robertson took the mound in game 2 for the Panthers.

Chief Moses Yellowhorse started for Little Rock but lasted only two-thirds of an inning.

The game was tied 3-3 after nine innings.

In the bottom of the tenth Panthers pitcher Robertson hit a “high, wide, and handsome” fly to deep center, scoring Dutch Hoffman from third. Thus, Robertson won his game both on the mound and at the plate.

Score: Class B Panthers 4, Class A Travelers 3

The next three games were played in Little Rock—twelve hours away by train ride (remember: no airliners).

What about the majority of Panthers fans, who could not go to Little Rock for those three games (remember: no radio)?

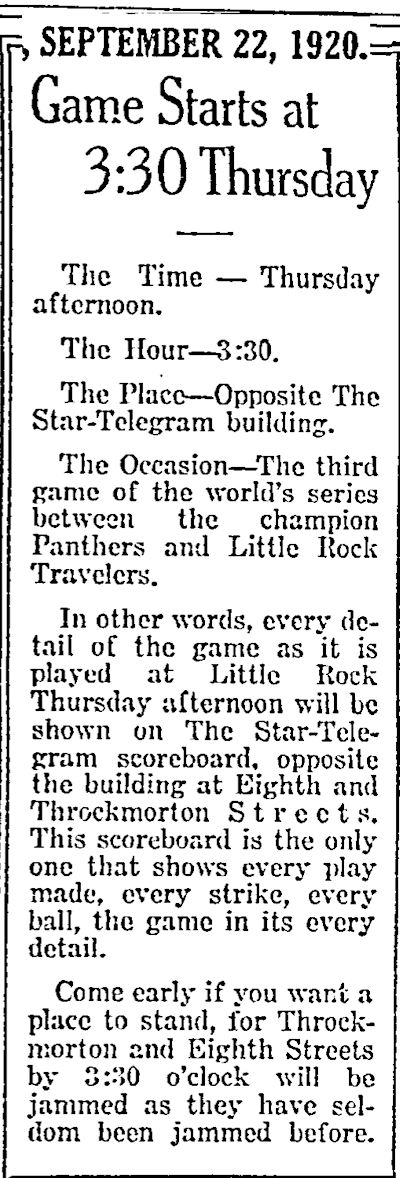

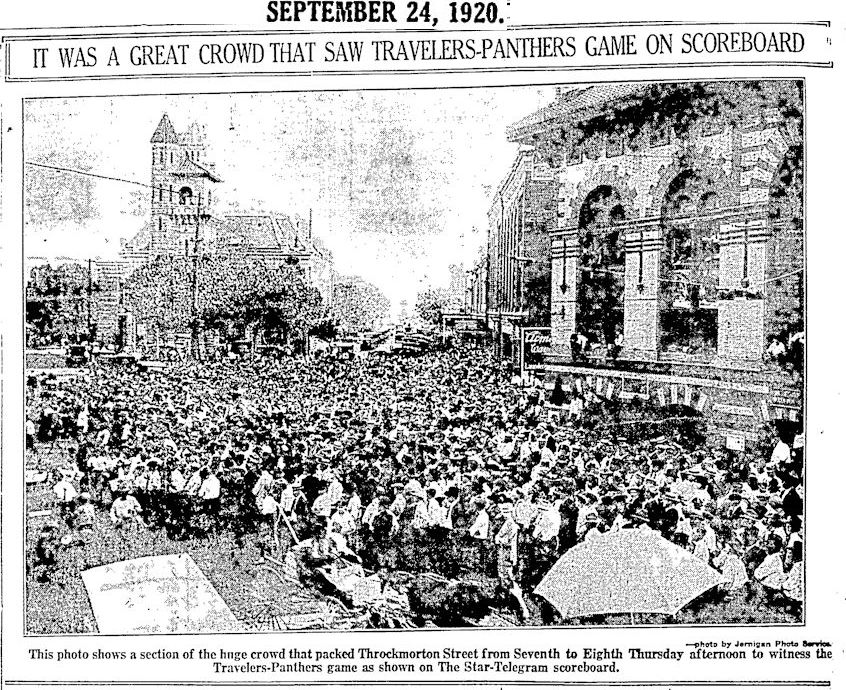

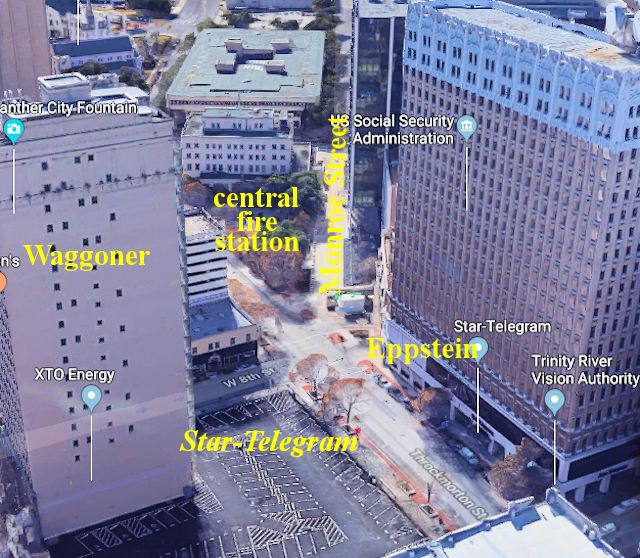

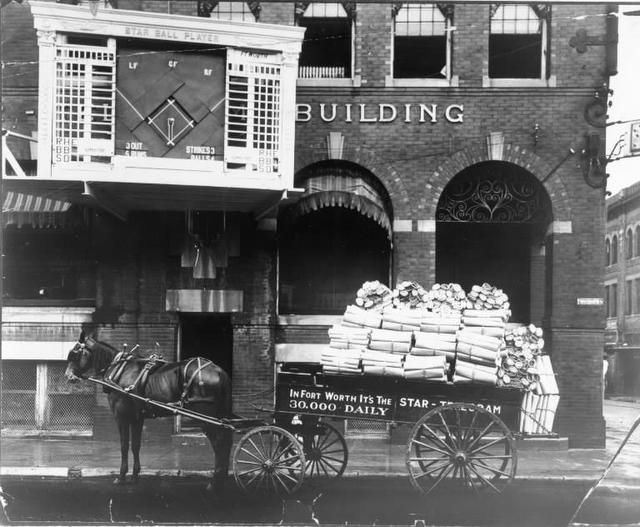

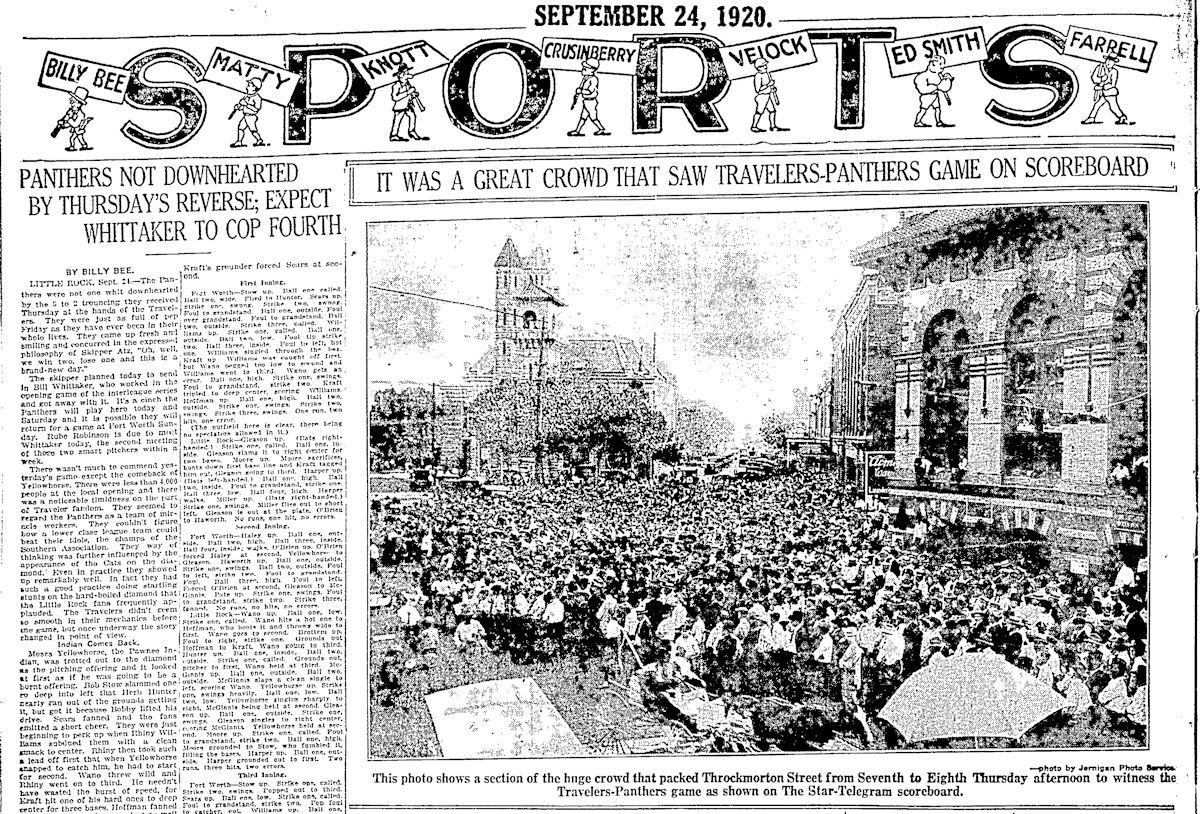

For Panthers fans left behind in Fort Worth the Star-Telegram provided the next best thing to a box seat in Little Rock: a scoreboard outside the newspaper building at the intersection of Throckmorton, West 8th, and Monroe streets downtown. The Star-Telegram building was located where the west parking lot of the Waggoner Building is today.

For Panthers fans left behind in Fort Worth the Star-Telegram provided the next best thing to a box seat in Little Rock: a scoreboard outside the newspaper building at the intersection of Throckmorton, West 8th, and Monroe streets downtown. The Star-Telegram building was located where the west parking lot of the Waggoner Building is today.

The scoreboard would present the play-by-play from updates sent by telegraph from the Little Rock ballpark. A bell on the scoreboard rang when a run was scored.

The 1920 photo looks south up Monroe Street, which in 1920 ended at Throckmorton, not at West 10th Street. The Star-Telegram building is to the left of the photo. The building with a tower is the central fire station. The building on the right is the Eppstein Building (see below), located where today’s Star-Telegram Building (originally The Fair Building) stands today.

During the games in Little Rock the intersection was closed to cars, and police were stationed around the surrogate ballpark.

Just as at a real ballpark, fans cheered, booed, bet and, yes, ate peanuts and Cracker Jacks as they read the play-by-play.

Note the horse and buggy in the foreground.

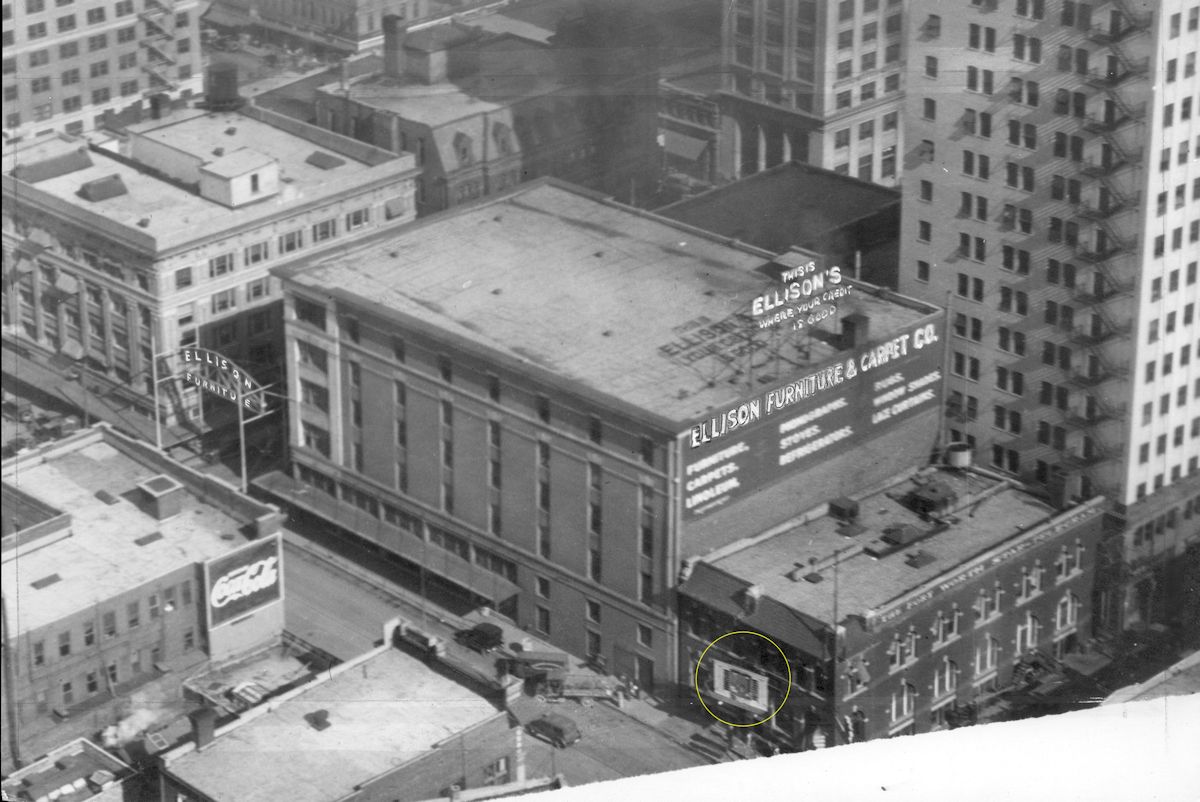

This photo shows the Ellison building on the left and the Star-Telegram building on the right. The scoreboard is in the yellow circle. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Libraries.)

This photo from the Star-Telegram archives shows the “Star Ball Player” scoreboard. The scoreboard displayed hits, runs, balls, strikes, and outs inning by inning. There was a catwalk in front of the scoreboard for the scorekeeper, who updated the play-by-play from telegraph reports.

This photo from the Star-Telegram archives shows the “Star Ball Player” scoreboard. The scoreboard displayed hits, runs, balls, strikes, and outs inning by inning. There was a catwalk in front of the scoreboard for the scorekeeper, who updated the play-by-play from telegraph reports.

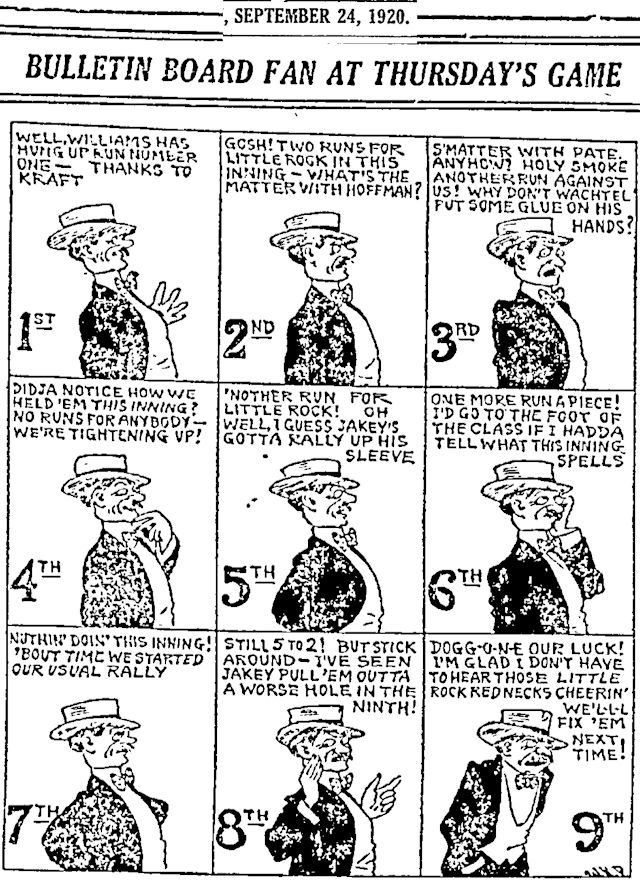

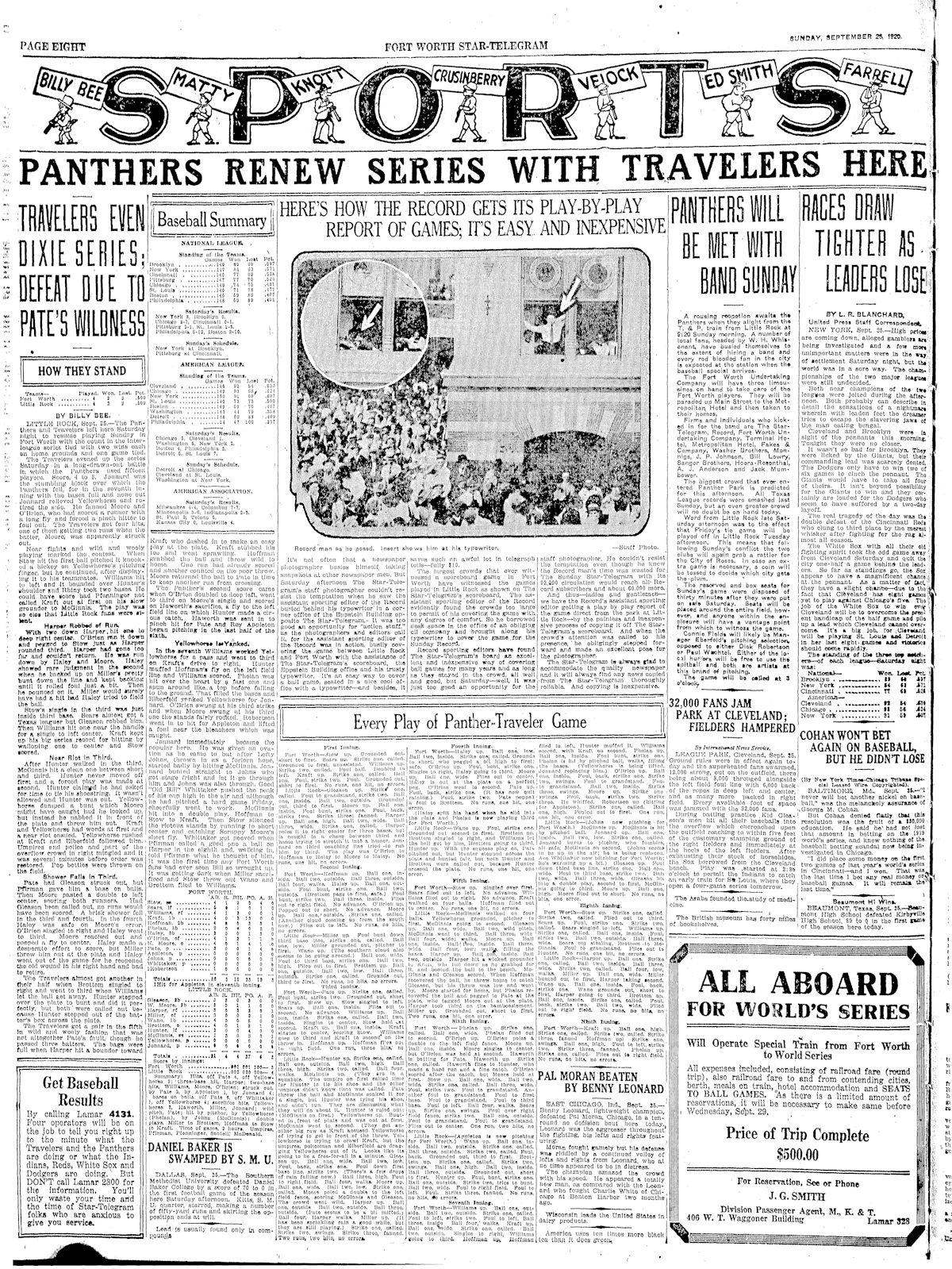

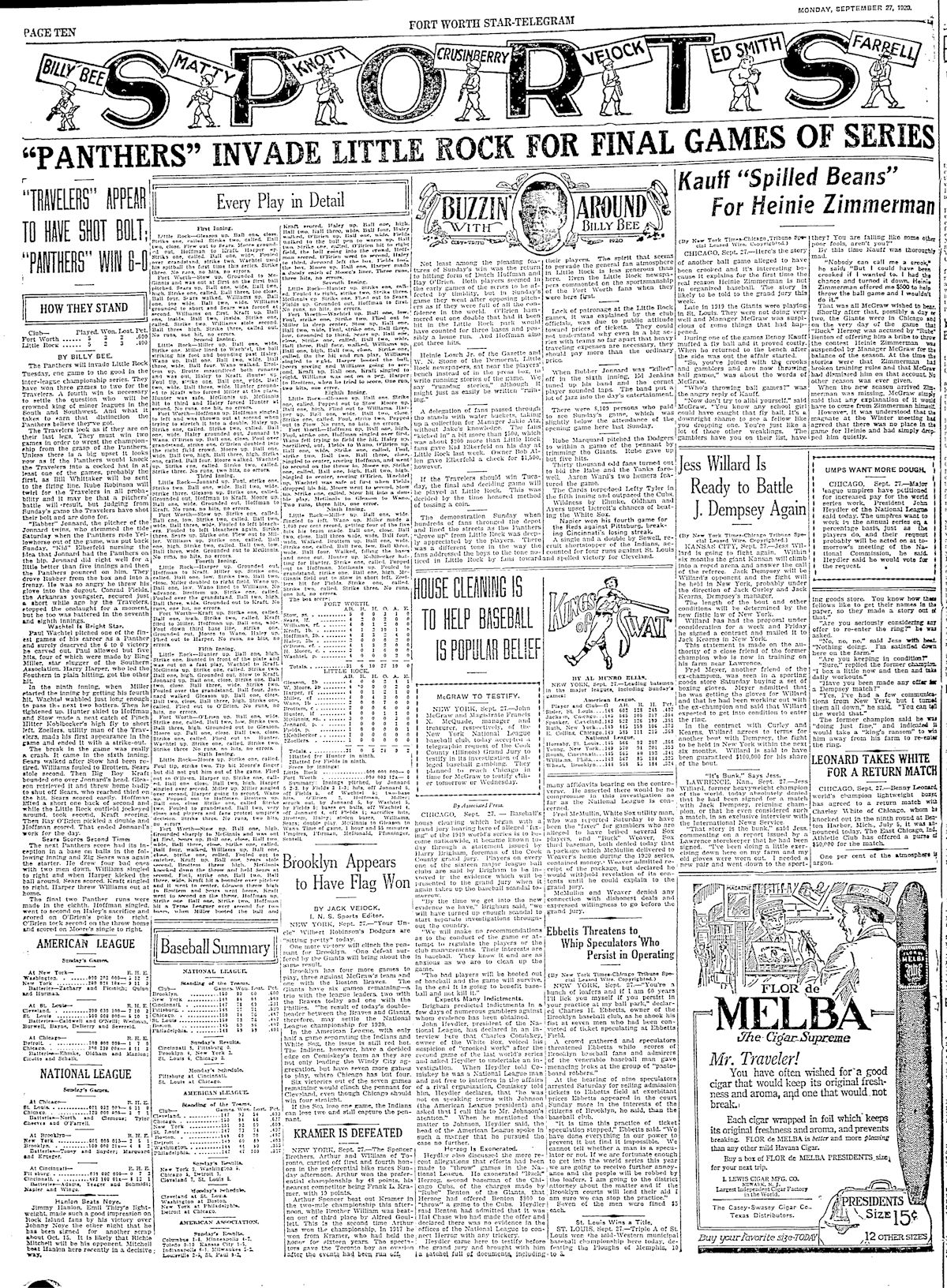

This cartoon depicts a fan following the play-by-play on the Star-Telegram scoreboard.

This cartoon depicts a fan following the play-by-play on the Star-Telegram scoreboard.

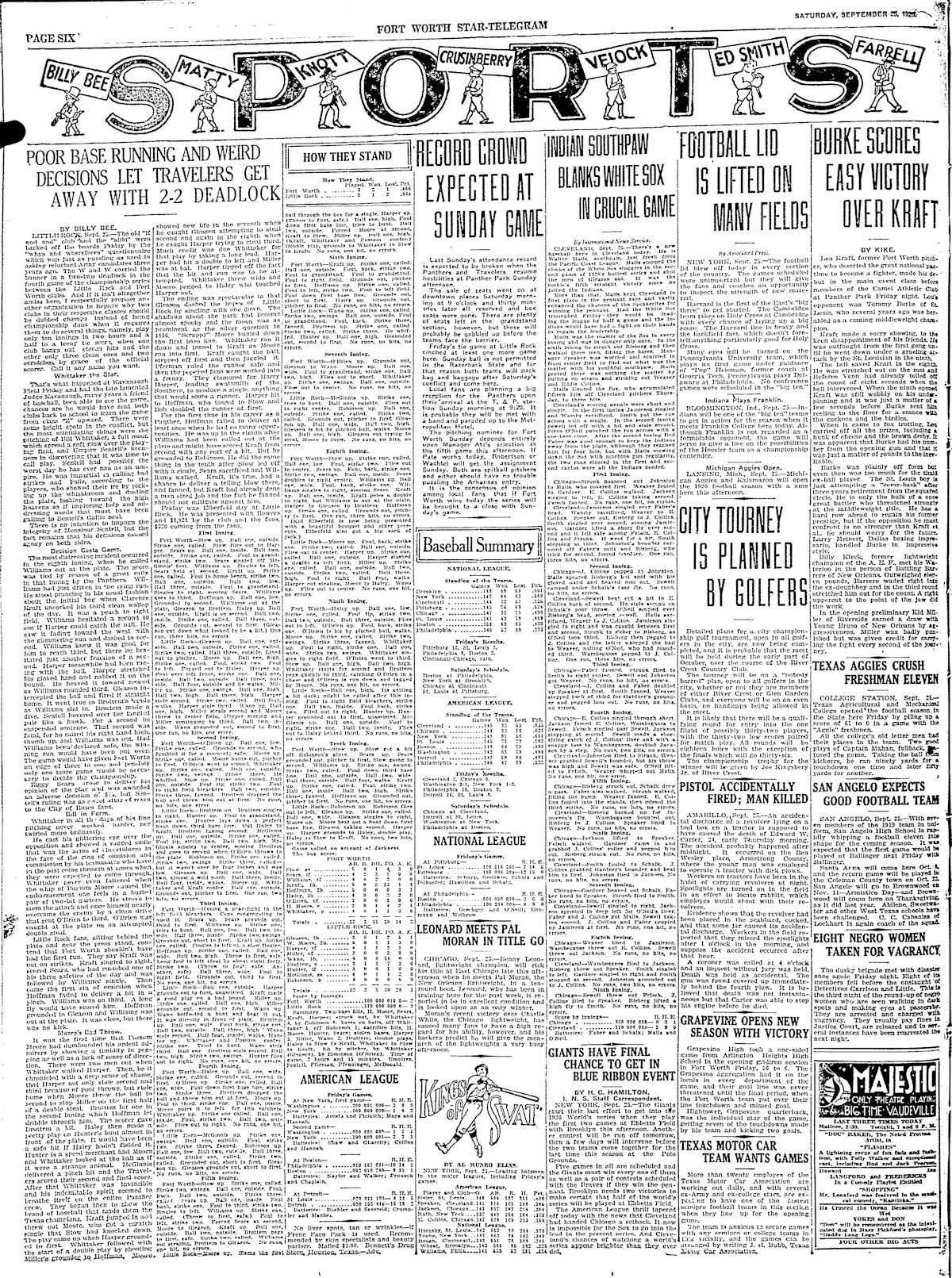

Those fans on Throckmorton Street had more to boo than cheer in game 3. Panthers pitchers Joe Pate and Paul Wachtel gave up fourteen hits, whereas Little Rock’s Chief Moses Yellowhorse held the Panthers to five hits in a 5-2 loss.

Those fans on Throckmorton Street had more to boo than cheer in game 3. Panthers pitchers Joe Pate and Paul Wachtel gave up fourteen hits, whereas Little Rock’s Chief Moses Yellowhorse held the Panthers to five hits in a 5-2 loss.

Attendance at Little Rock was less than four thousand.

Game 4, like game 2, went ten innings. But this time the game was called because of darkness.

Game 4, like game 2, went ten innings. But this time the game was called because of darkness.

Yes, darkness.

No radio, no airliners, no ballpark lights.

The score was 2-2. Pitcher Bad Eye Whittaker again went the distance for the Panthers.

Even at ten innings, the game was played in just 2:15 hours.

Game 5 was another tight game.

In the third inning after Panthers catcher Possum Moore threw out Little Rock pitcher Chief Moses Yellowhorse at first base on a bunt, Yellowhorse and Panthers first baseman Big Boy Kraft had words.

Yellowhorse rushed at Kraft, and Little Rock manager Kid Elberfeld ran onto the field to protect his pitcher. Umpires and police officers and fans from the right field stands mingled around first base, pop bottles were thrown onto the field, and order was not restored for several minutes.

In the seventh inning, trailing by one run, the Panthers had the bases loaded and none out but did not score.

Panthers pitchers—four of them!—gave up only four hits but walked six as Little Rock evened the series 2-2 with a 4-3 win.

The next day was Sunday. Baseball on the Sabbath was not allowed in Arkansas, so the two teams took that twelve-hour train trip back to Fort Worth.

The Panthers were met at the Texas & Pacific train station by fans who had hired a band. The Panthers were paraded up Main Street to the Metropolitan Hotel. Fort Worth Undertaking Company provided three limousines for the Panthers.

The photo shows a sportswriter of the rival Fort Worth Record covering game 5 by monitoring the Star-Telegram’s play-by-play scoreboard. Rather than spend money by traveling to Little Rock or leasing a telegraph line to get the play-by-play, the Record stayed home and rented an office with a window in the Eppstein Building opposite the Star-Telegram scoreboard!

The photo shows a sportswriter of the rival Fort Worth Record covering game 5 by monitoring the Star-Telegram’s play-by-play scoreboard. Rather than spend money by traveling to Little Rock or leasing a telegraph line to get the play-by-play, the Record stayed home and rented an office with a window in the Eppstein Building opposite the Star-Telegram scoreboard!

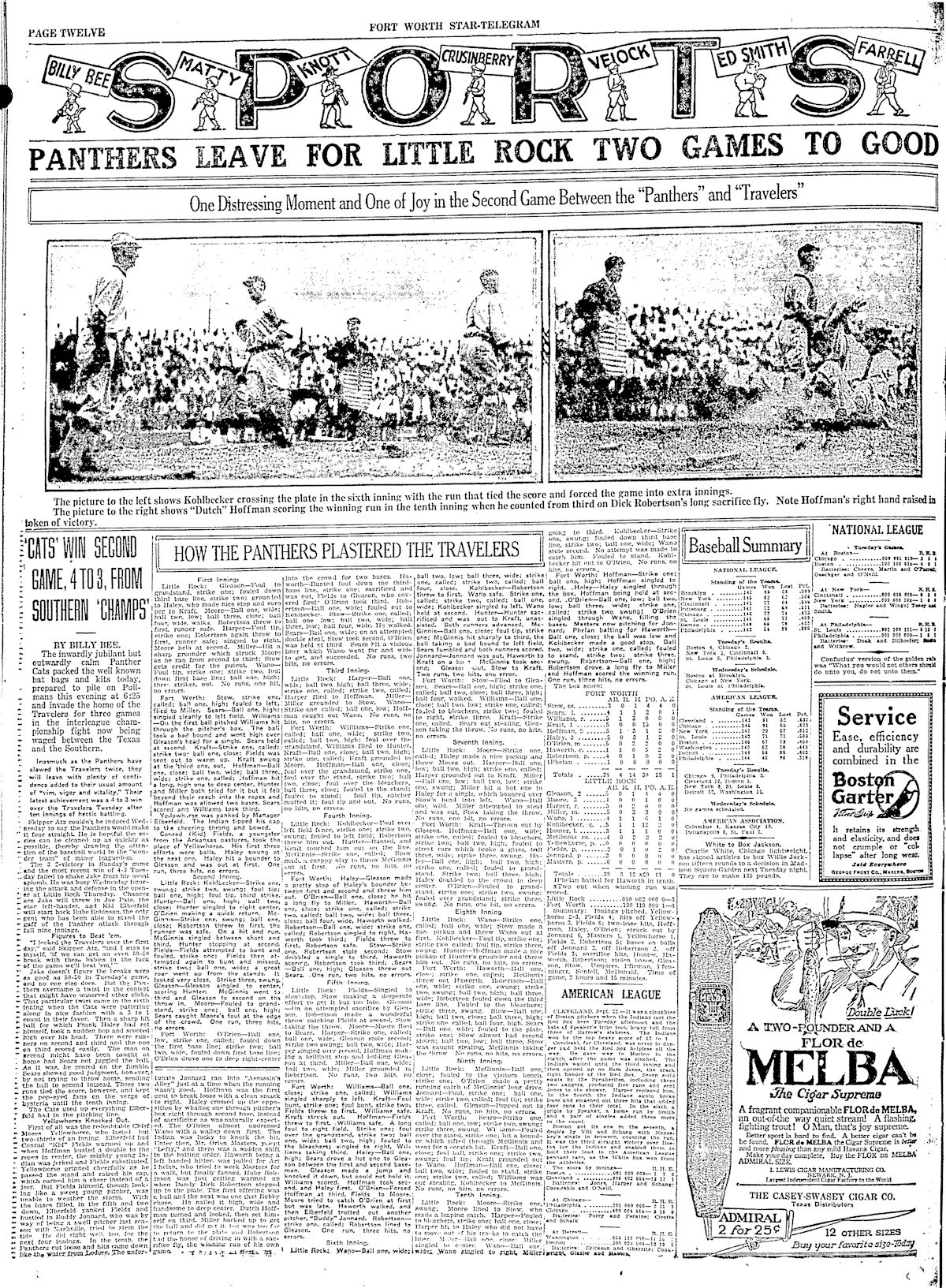

On Sunday 8,109 fans—slightly below the record set the previous Sunday—overflowed Panther Park for game 6.

On Sunday 8,109 fans—slightly below the record set the previous Sunday—overflowed Panther Park for game 6.

For the Panthers Paul Wachtel pitched another complete game, giving up only five hits.

Score: Class B Panthers 6, Class A Travelers 0

The Panthers now led the best-of-seven series 3-2 (with one tie). One more win, and the Panthers would be the dukes of Dixie.

But first, another twelve-hour train ride back to Little Rock.

On September 28 game 7 in Little Rock was not pretty. Neither team played its best baseball, and the final score came down to which team would out-bad the other.

On September 28 game 7 in Little Rock was not pretty. Neither team played its best baseball, and the final score came down to which team would out-bad the other.

Panthers pitcher Bad Eye Whittaker gave up thirteen hits and four walks, but Little Rock stranded twelve baserunners and made five errors.

In the sixth inning Little Rock manager Kid Elberfeld, frustrated because his team was behind 4-1 with chances running out, rushed onto the field to protest a call by home plate umpire Paul Sentell. Elberfeld returned to the bench but continued to “jaw” at Sentell. The umpire ejected Elberfeld, but Elberfeld refused to leave. Sentell took out his pocketwatch and consulted it. Still Elberfeld didn’t budge. Then the umpire called for police officers. Finally Elberfeld left the ballpark.

Three innings later the Travelers and their hope for winning the postseason series also left the ballpark.

Score: Class B Panthers 4, Class A Travelers 2

The Fort Worth Panthers were the champions of not only the Texas League but also the southern minor leagues. They were the dukes of Dixie.

The Fort Worth Panthers were the champions of not only the Texas League but also the southern minor leagues. They were the dukes of Dixie.

The timing of the Panthers’ big moment was unfortunate: They had to share the front page with news about attempts to fix the upcoming major league World Series and news about more confessions in the 1919 Chicago White Sox game-fixing scandal.

Panthers pitcher Bad Eye Whittaker was the series hero, winning game 1 and game 7 and pitching the tied ten-inning game 4. He pitched three complete games, a total of twenty-nine innings.

The series was a study in small ball: Not one home run was hit in 446 total at-bats by the two teams.

The average duration of each game was a brisk two hours.

Fans met the returning Panthers at the Fort Worth train station with cheers of “Hail, hail, the gang’s all here” and paraded the team up Main Street in automobiles to the Fort Worth Club, where the Panthers were honored at a dinner. Amon Carter was toastmaster. He lauded manager Atz as “the skipper who had successfully piloted the best club ever gathered in a minor league.”

Each player was called to the podium and spoke a few words, mainly expressing appreciation for the support of Fort Worth fans.

Meanwhile Star-Telegram sports columnist Billy Bee speculated that the Texas League-Southern Association postseason series might become an annual competition.

The Star-Telegram in an editorial thanked the Panthers for bringing glory to Texas and Fort Worth and proving that the Class B Texas League was more than the equal of the Class A Southern Association. The editorial pointed out that more fans monitored the games on the Star-Telegram scoreboard in the middle of Throckmorton Street than attended the games in person in Little Rock.

The Star-Telegram in an editorial thanked the Panthers for bringing glory to Texas and Fort Worth and proving that the Class B Texas League was more than the equal of the Class A Southern Association. The editorial pointed out that more fans monitored the games on the Star-Telegram scoreboard in the middle of Throckmorton Street than attended the games in person in Little Rock.

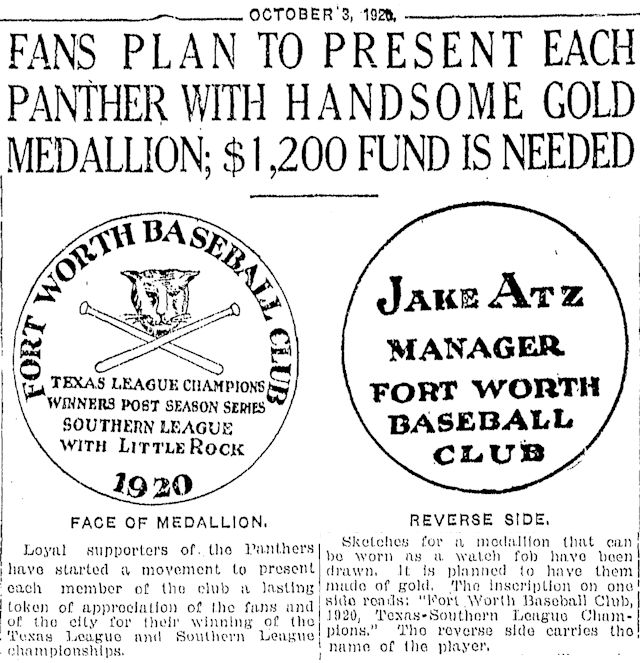

The Star-Telegram announced that fans planned to collect donations and present each Panther with a medallion—the equivalent of a World Series ring.

The Star-Telegram announced that fans planned to collect donations and present each Panther with a medallion—the equivalent of a World Series ring.

Such gestures of fan appreciation would become expensive. Because just as the 1920s roared, so did the Fort Worth Panthers. For six years beginning with their golden summer of 1920 Jake Atz and his Atz Cats would win 632 games against 282 losses for a percentage of .692. And Billy Bee’s speculation would prove correct: The Texas League-Southern Association postseason series in 1921 would become an annual competition: the “Dixie Series.” The Panthers would play in the Dixie Series—the World Series of the southern minor leagues—six times in six years and win five times, one of the best records in minor league history.

And largely because of the performance of the Fort Worth Panthers in 1920, in 1921 the Texas League would be promoted to Class A.