For a quarter-century Amon Carter (see Part 1) was the face of Fort Worth to the rest of Texas and the face of Texas to the rest of the world.

He fulfilled those roles by being, bar none, the most unabashed, unblinking promoter of Fort Worth and Texas (especially west Texas). And to do that promoting he adopted the persona of the stereotypical Texan: a cowboy.

And then he exaggerated the stereotype.

Jerry Flemmons in Amon: The Life of Amon Carter, Sr. of Texas, speculates that Carter, denied much of a childhood, adopted the two-gun, rootin-tootin’ persona as an adult so he could play cowboy the rest of his life.

And he did.

He was capable of wearing a custom-tailored conventional suit and tie. But he was at his happiest when he wore a capacious cowboy hat, fancy western boots, tailored trousers, two pearl-handled pistols in hand-tooled holsters, chaps, spurs, a bandanna.

Alva Johnston, profiling Carter for the Saturday Evening Post, said Carter loved a crowd like a pickpocket does. Carter appeared, in full cowboy costume, at sundry public events—parades, stock shows and rodeos, college football games, political rallies, holiday celebrations.

To the occasional chagrin of friends and family and fellow titans, he was apt to holler “Yippie!” and “Whoopee for Fort Worth!” at the drop of a ten-gallon hat.

Carter was an obsessive collector, from string and rubber bands to paintings and statuary. He collected all things western: arrowheads, guns, mounted longhorn and buffalo heads, steer horns. He bought and restored the log cabin of Isaac Parker. Perhaps the cabin reminded him of his own Horatio Algeresque beginnings.

Carter was an obsessive collector, from string and rubber bands to paintings and statuary. He collected all things western: arrowheads, guns, mounted longhorn and buffalo heads, steer horns. He bought and restored the log cabin of Isaac Parker. Perhaps the cabin reminded him of his own Horatio Algeresque beginnings.

On the world stage Carter mingled with household names: Harry Truman, Sam Rayburn, H. L. Mencken, William Randolph Hearst, FDR, J. C. Penney, W. C. Stripling, Sid Richardson, Gary Cooper, Edgar Bergen, Eddie Cantor, Fiorella LaGuardia, Charles Lindbergh, Eisenhower.

Will Rogers was among his closest celebrity friends.

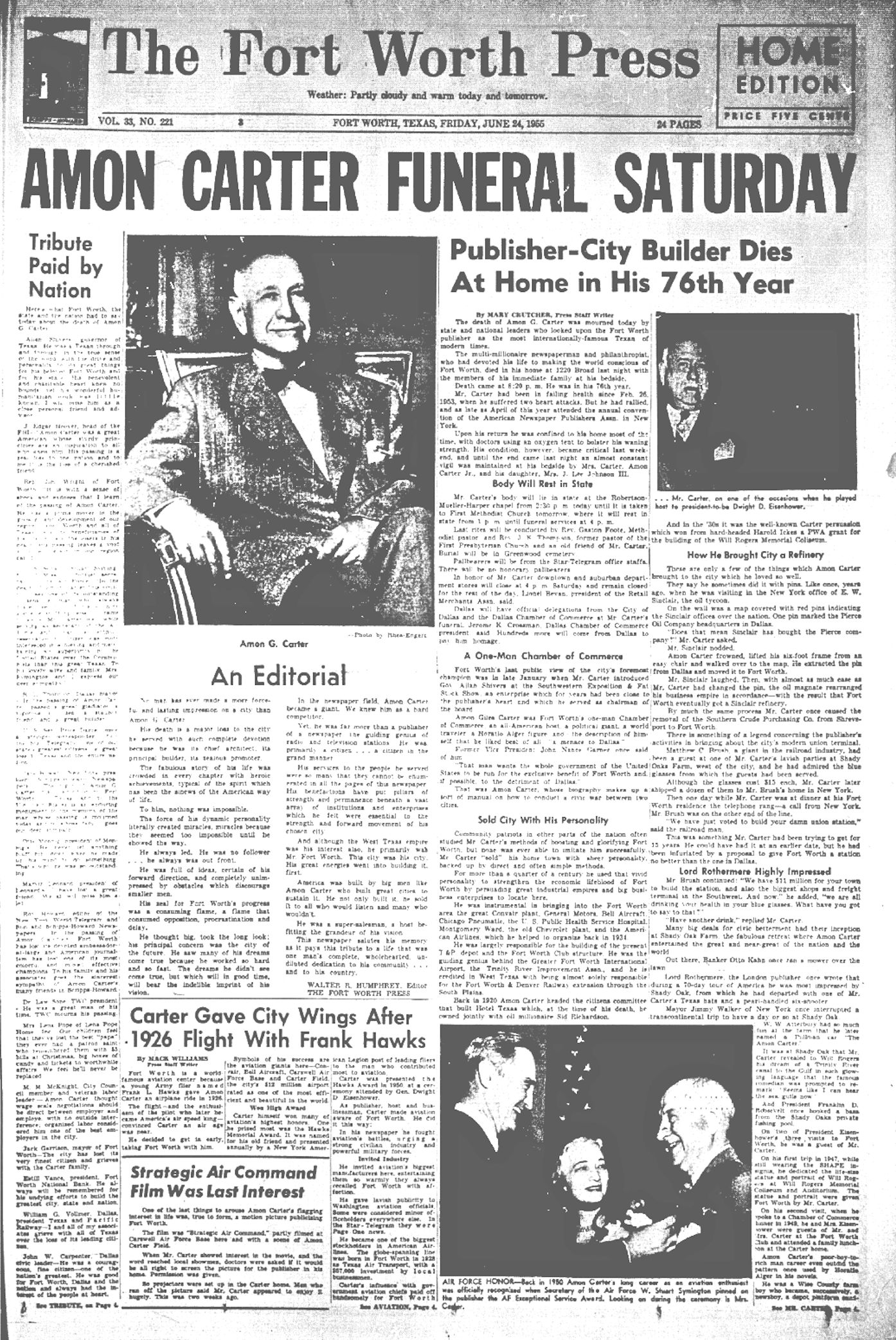

Amon Carter with, from left, Frank Hawks, W. T. Waggoner, and Will Rogers in 1931 at Waggoner’s Arlington Downs. Frank Hawks was a record-setting aviator known as the “fastest airman in the world.” (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Libraries.)

William G. Fuller, who helped develop Meacham Field from a cow pasture to a commercial airport, said Hawks was the first person to take aloft Amon Carter in an airplane.

“Hawks flew him on an emergency trip to Washington in an old open-seated plane, and Mr. Carter told me when he got back that the flight made him sick as a dog.”

Carter with Will Rogers and Eleanor Roosevelt.

Carter with Will Rogers and Eleanor Roosevelt.

Carter with Fort Worth oil millionaire Sid Richardson and Dwight D. Eisenhower. Richardson once said, “Amon does my talking for me, and every time he does, it costs me money.”

Carter with Fort Worth oil millionaire Sid Richardson and Dwight D. Eisenhower. Richardson once said, “Amon does my talking for me, and every time he does, it costs me money.”

Carter was equally at ease with a cigar, a card deck, a shot glass, and an expletive—all of which were in abundant supply at his Shady Oak Farm at Lake Worth, where he entertained the famous and powerful who passed through town.

He had his own private-label whiskey: Shady Oak.

Carter even had the Stetson hat company keep him supplied with copies of a custom cowboy hat—the Shady Oak model. Carter gave them to guests at his farm. Being given a Shady Oak hat by Carter was receiving his personal stamp of approval.

Carter also entertained in his suite in the Fort Worth Club (he was club president): FDR, Gene Autry, Bob Hope, Presidents Eisenhower and Lyndon Johnson, J. Edgar Hoover, Eddie Rickenbacker, Will Rogers, Jack Dempsey, General Douglas MacArthur.

Carter could charm his guests, but he was not always easy to work for. He was prone to anger. “Mad spells,” his personal secretary, Katrine Deakins, called his outbursts.

“Amon the Terrible,” one subordinate labeled him.

He was not always easy to live with. First wife Zettie in her divorce suit said Carter “grew censorious of plaintiff and her . . . humble methods of living.” Second wife Nenetta divorced him because “I got tired of being married to the Chamber of Commerce.”

(Third wife Minnie Meacham Carter stayed with him to the end.)

Amon Carter’s real wife, of course, was the Star-Telegram, and under Carter’s leadership the Star-Telegram prospered. From 1923 until after World War II the Star-Telegram had the largest circulation in the South and a circulation area of 370,000 square miles, most of that in west Texas. Like all good marriages, theirs was symbiotic: Carter made the newspaper influential; the newspaper made Carter rich.

But as much as he enjoyed making money, he enjoyed giving it away even more—to hospitals and colleges (and college students), to accident victims, widows, police and firefighter groups, residents of nursing homes and orphanages.

He founded the Amon Carter Foundation and Amon Carter Museum of American Art.

His Star-Telegram was a family to its employees. Employee who needed jobs were kept on the payroll after most bottom line-driven companies would have dismissed them.

Blind John operated a snack concession on the second floor.

Newsie Monroe Odom sold the Star-Telegram on the sidewalk and schmoozed with his boss for fifty-nine years. Monroe, with his twisted foot and speech impediment, was a favorite of Carter.

During World War II Star-Telegram employees who were in uniform, Flemmons writes, were considered to be merely “out of the office.” They still received their Christmas bonus, were mailed copies of the newspaper overseas.

Amon Carter was at the height of his back-slapping, arm-twisting, check-writing boosterism from 1920 to 1950.

In 1923 Carter persuaded the Texas legislature to establish a four-year college (now Texas Tech University) in Lubbock. He was the first chairman of the school’s board of directors.

In 1923 Carter persuaded the Texas legislature to establish a four-year college (now Texas Tech University) in Lubbock. He was the first chairman of the school’s board of directors.

In 1925 Carter and the Star-Telegram campaigned for a municipal airport to be built near the helium plant north of Fort Worth.

In 1925 Carter and the Star-Telegram campaigned for a municipal airport to be built near the helium plant north of Fort Worth.

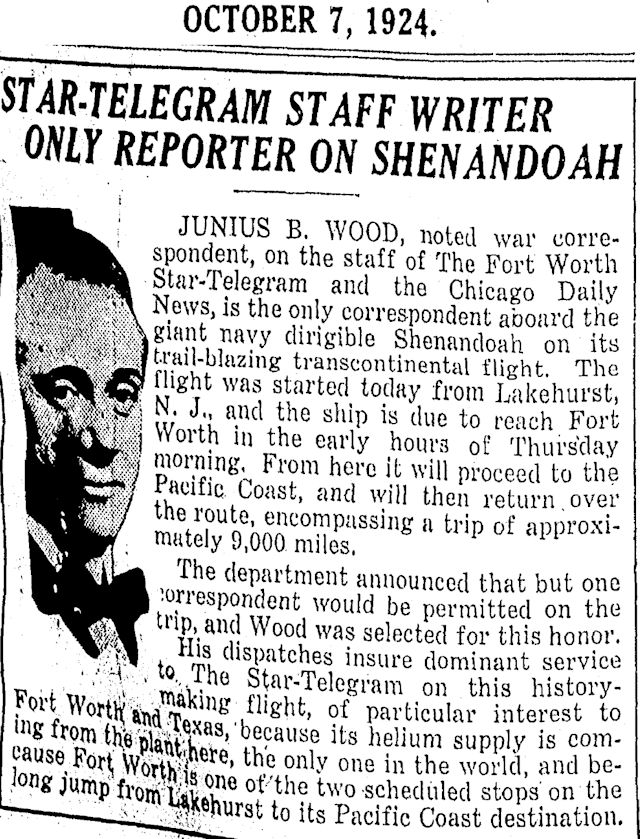

To Amon Carter the Star-Telegram was not just a way to report news. It was a way to make news. As the paper had done with Harry Houdini in 1916, when the USS Shenandoah dirigible made the first flight of a rigid airship across North America in 1928 and moored at the helium plant, the Star-Telegram crowed on page 1 that it had the only correspondent on board.

To Amon Carter the Star-Telegram was not just a way to report news. It was a way to make news. As the paper had done with Harry Houdini in 1916, when the USS Shenandoah dirigible made the first flight of a rigid airship across North America in 1928 and moored at the helium plant, the Star-Telegram crowed on page 1 that it had the only correspondent on board.

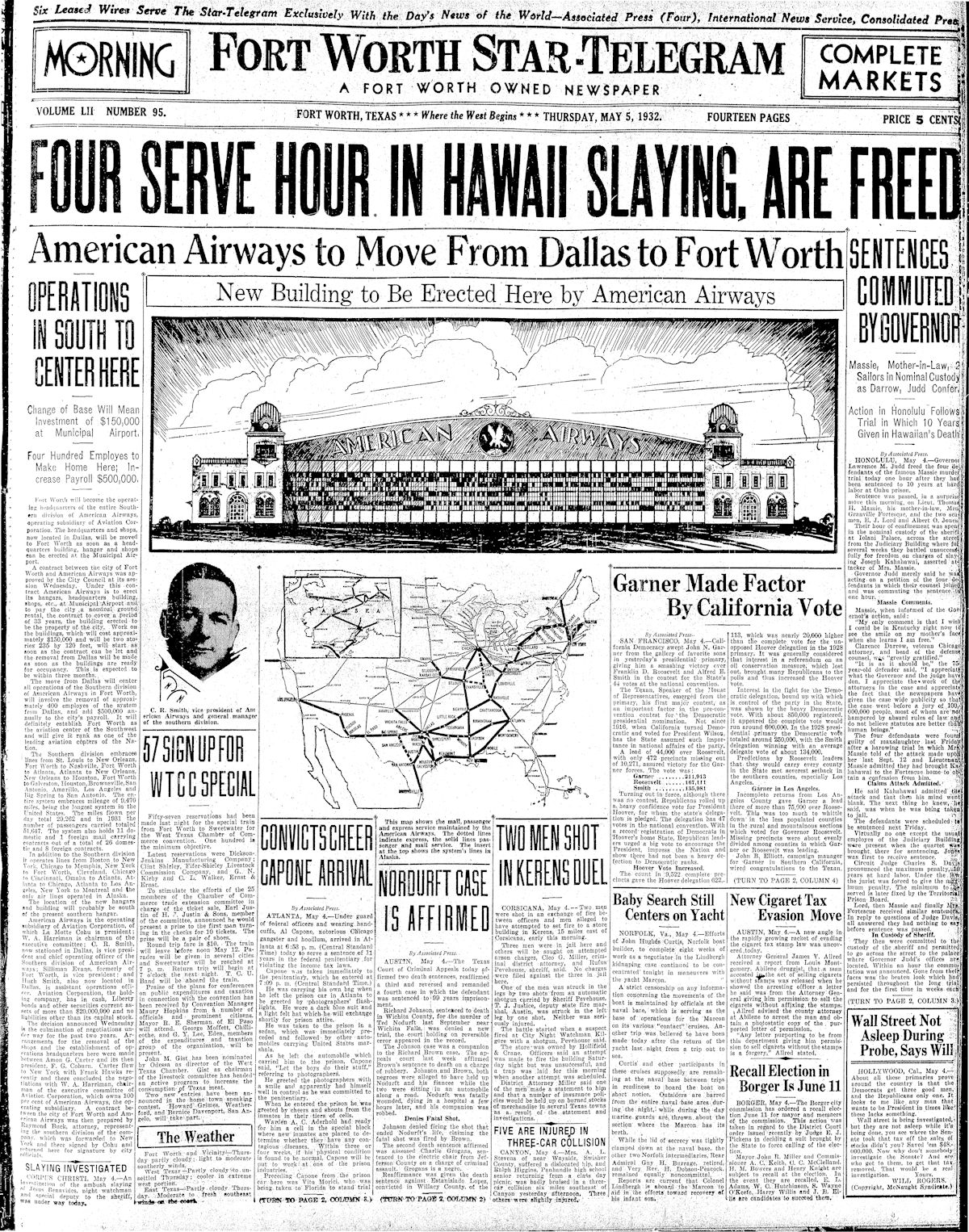

After the municipal airport was built, in 1932 Carter helped persuade American Airways to move its headquarters from Dallas to Fort Worth and build new facilities at Municipal Airport (Meacham International Airport today). In an editorial the Dallas Journal lamented its city’s loss with the headline “Amon Cartered Again.” American Airways became American Airlines in 1934. The major stockholder of American Airlines? Amon Carter.

After the municipal airport was built, in 1932 Carter helped persuade American Airways to move its headquarters from Dallas to Fort Worth and build new facilities at Municipal Airport (Meacham International Airport today). In an editorial the Dallas Journal lamented its city’s loss with the headline “Amon Cartered Again.” American Airways became American Airlines in 1934. The major stockholder of American Airlines? Amon Carter.

When Dallas was selected as the site for the official Texas centennial celebration in 1936, Carter decreed that Fort Worth would out-Dallas Dallas with its own wingding: the Frontier Centennial. Carter even got his buddy FDR to officially open the celebration. FDR, aboard his schooner in the Atlantic Ocean, pressed the key of a wireless transmitter and by radio and telegraph cut a lariat stretched across the entrance to the Frontier Centennial grounds 1,500 miles away.

When Dallas was selected as the site for the official Texas centennial celebration in 1936, Carter decreed that Fort Worth would out-Dallas Dallas with its own wingding: the Frontier Centennial. Carter even got his buddy FDR to officially open the celebration. FDR, aboard his schooner in the Atlantic Ocean, pressed the key of a wireless transmitter and by radio and telegraph cut a lariat stretched across the entrance to the Frontier Centennial grounds 1,500 miles away.

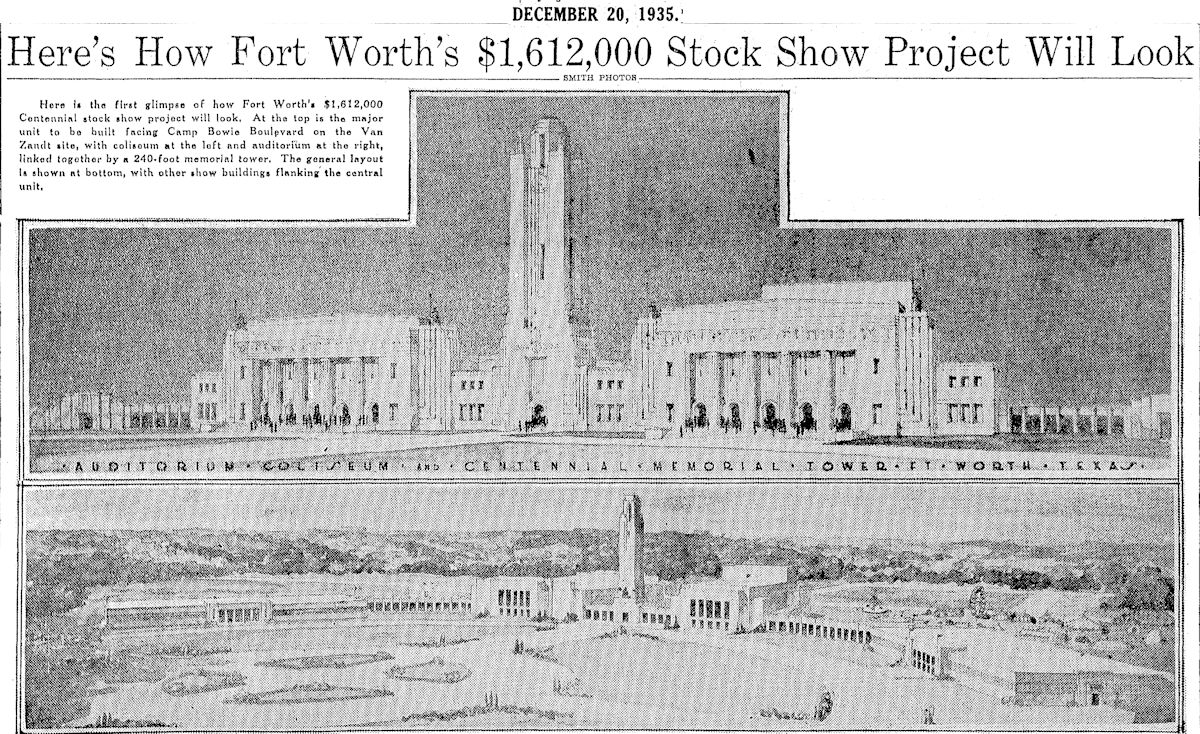

While Carter was at it, he helped the city get funding to build the coliseum and auditorium from which our cultural district grew. He also got the complex named for his friend Will Rogers, who had been killed in 1935.

While Carter was at it, he helped the city get funding to build the coliseum and auditorium from which our cultural district grew. He also got the complex named for his friend Will Rogers, who had been killed in 1935.

In the 1940s Carter, as president of the Big Bend National Park board, was instrumental in making the park a reality in 1944. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Star-Telegram Collection.)

In the 1940s Carter, as president of the Big Bend National Park board, was instrumental in making the park a reality in 1944. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Star-Telegram Collection.)

The year 1941 brought another world war and another response from Carter. He helped persuade the federal government to build the bomber plant in Fort Worth. Originally Tulsa, not Fort Worth, was to be awarded the plant. But Carter cajoled. Okay, the government said, both Tulsa and Fort Worth can have bomber plants. Originally plans called for the two plants to be identical. But Carter, Flemmons writes, kept cajoling. Carter wanted the Fort Worth plant to be bigger than the Tulsa plant. Flemmons writes: “Amon demanded a change. Army architects added two more support columns and twenty-nine feet to appease the publisher. Fort Worth had the world’s largest aircraft factory.”

The year 1941 brought another world war and another response from Carter. He helped persuade the federal government to build the bomber plant in Fort Worth. Originally Tulsa, not Fort Worth, was to be awarded the plant. But Carter cajoled. Okay, the government said, both Tulsa and Fort Worth can have bomber plants. Originally plans called for the two plants to be identical. But Carter, Flemmons writes, kept cajoling. Carter wanted the Fort Worth plant to be bigger than the Tulsa plant. Flemmons writes: “Amon demanded a change. Army architects added two more support columns and twenty-nine feet to appease the publisher. Fort Worth had the world’s largest aircraft factory.”

Carter also helped persuade the government to build Tarrant Field Airdrome (later Carswell Air Force Base) adjacent to the bomber plant.

(Vice President John Nance Garner of Texas once said of Carter: “That man wants the whole government of the United States to be run for the exclusive benefit of Fort Worth and if possible to the detriment of Dallas.”)

Carter christening the B-24 named City of Fort Worth. (Photo from Lockheed Martin Aeronautics Company.)

Carter christening the B-24 named City of Fort Worth. (Photo from Lockheed Martin Aeronautics Company.)

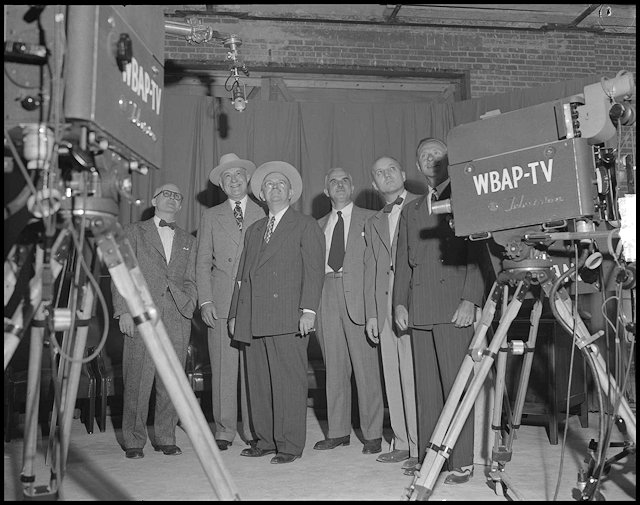

In 1948 Carter embraced the latest doodad: television. He added WBAP-TV to his communications empire. In the photo Carter is second from the left. Harold Hough is third from the left. (Photo from University of North Texas Libraries Special Collections.)

In 1948 Carter embraced the latest doodad: television. He added WBAP-TV to his communications empire. In the photo Carter is second from the left. Harold Hough is third from the left. (Photo from University of North Texas Libraries Special Collections.)

WBAP-TV went on the air with coverage of President Truman’s visit to Fort Worth.

WBAP-TV went on the air with coverage of President Truman’s visit to Fort Worth.

Three years later, in 1951 Amon helped persuade Bell Aircraft (now Bell Helicopter Textron) to relocate to the former Globe Aircraft plant on Blue Mound Road.

Three years later, in 1951 Amon helped persuade Bell Aircraft (now Bell Helicopter Textron) to relocate to the former Globe Aircraft plant on Blue Mound Road.

In 1952 Carter helped bring an auto assembly plant to the area for the second time, this one in Arlington. This photo shows him with a microphone at the groundbreaking for the plant. (Photo from Arlington Historical Society’s Fielder House Museum.)

In 1952 Carter helped bring an auto assembly plant to the area for the second time, this one in Arlington. This photo shows him with a microphone at the groundbreaking for the plant. (Photo from Arlington Historical Society’s Fielder House Museum.)

The man who would not take “no” for an answer did not suffer many setbacks. But amid his myriad successes, one of Carter’s greatest disappointments was the failure of federal and local governments to make the Trinity River navigable from Fort Worth to the gulf. Carter, as executive committee chairman of the Trinity River Canal Association, campaigned for canalization for a quarter-century. His go-to reporter, C. L. Richhart, was assigned to cover Carter’s pet project.

The man who would not take “no” for an answer did not suffer many setbacks. But amid his myriad successes, one of Carter’s greatest disappointments was the failure of federal and local governments to make the Trinity River navigable from Fort Worth to the gulf. Carter, as executive committee chairman of the Trinity River Canal Association, campaigned for canalization for a quarter-century. His go-to reporter, C. L. Richhart, was assigned to cover Carter’s pet project.

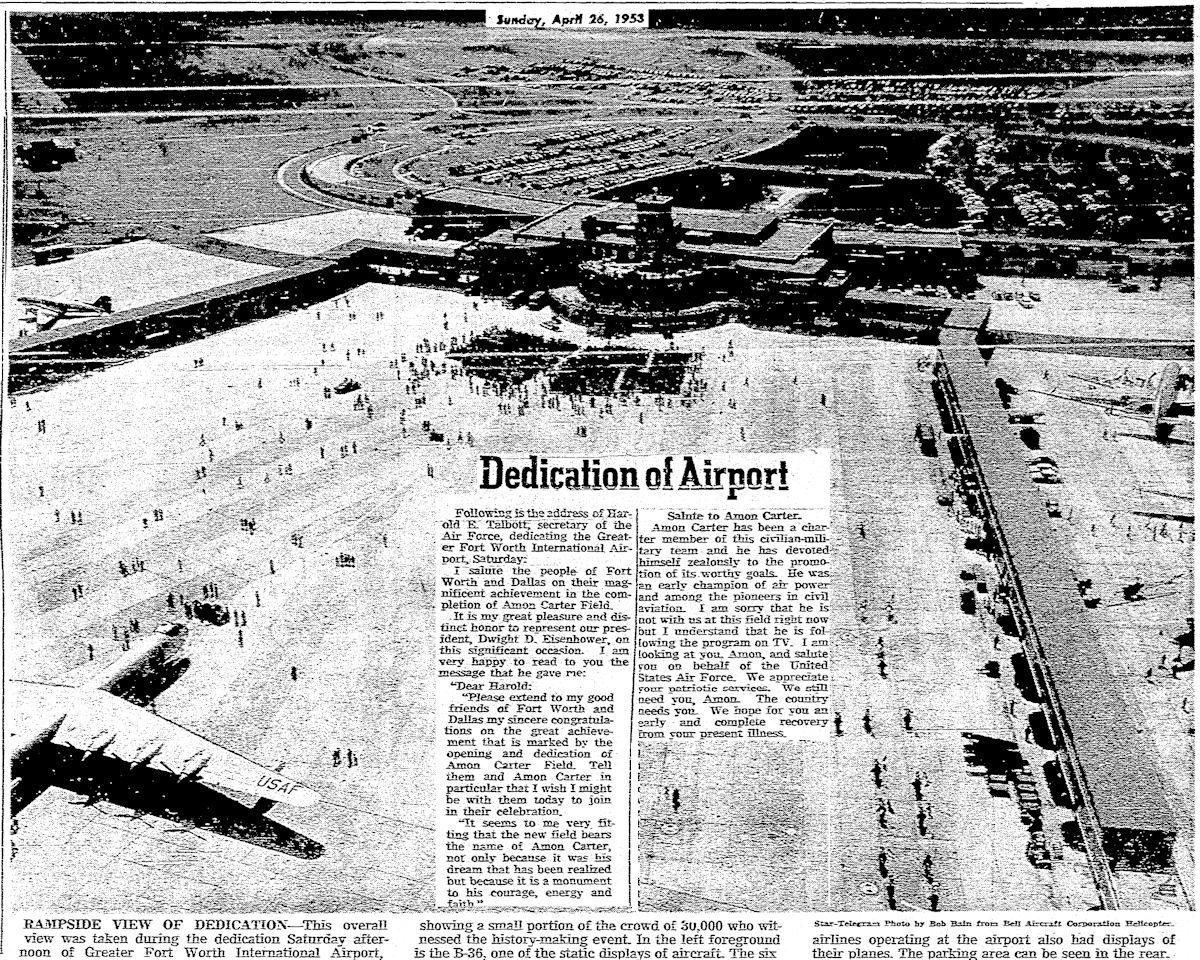

In the early 1950s Carter promoted an international airport for Fort Worth-Dallas (with emphasis on Fort Worth). In 1953 that airport became a reality, but Carter, who ate too fast, drank too much, and slept too little, was gravely ill and could not attend the dedication of the airport named for him. (Amon Carter Field/Greater Fort Worth International Airport became “Greater Southwest International Airport.”) Harold Talbott, secretary of the Air Force, spoke at the dedication and said he hoped for Carter’s “complete recovery.”

In the early 1950s Carter promoted an international airport for Fort Worth-Dallas (with emphasis on Fort Worth). In 1953 that airport became a reality, but Carter, who ate too fast, drank too much, and slept too little, was gravely ill and could not attend the dedication of the airport named for him. (Amon Carter Field/Greater Fort Worth International Airport became “Greater Southwest International Airport.”) Harold Talbott, secretary of the Air Force, spoke at the dedication and said he hoped for Carter’s “complete recovery.”

But that was not to be. Two years later, on June 23, 1955, Amon Giles Carter—the face of Fort Worth, the face of Texas—died at his mansion near River Crest Country Club.

But that was not to be. Two years later, on June 23, 1955, Amon Giles Carter—the face of Fort Worth, the face of Texas—died at his mansion near River Crest Country Club.

When Carter died, Flemmons writes, half of Fort Worth’s population worked for companies that Carter had lured to town.

Tributes came in from all over the world, from publishers and political leaders and powerbrokers and celebrities. In Fort Worth businesses closed, flags were lowered to half-staff.

Walter Humphrey (of whom Carter was not overly fond), editor of the rival Fort Worth Press, wrote, “This newspaper salutes his memory as it pays this tribute to a life that was one man’s complete, wholehearted, undiluted dedication to his community . . . and to his country.”

On the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives Jim Wright perhaps took the best measure of the man when Wright paid tribute to Carter. Among his remarks: “Amon Carter was known as ‘Mr. West Texas’ because he embodied in larger measure than any other person the characteristics of spectacular success, gregarious generosity and extreme extroversion for which the region is noted. In a land of giants, he dwarfed them all.”

Mike GREAT post about Amon Carter. Question: Do you have any “info / post” about Amon buying the James Record local newspaper [the “Ft. Worth Record” ?] back in the early 1900’s ?? I’ve heard that BOTH of James’ sons, Phil & Tony, were long-time employees of the Star-Telegram —- and Amon also gave James a life-long “seat” on the “Board of Directors” of the Star-Telegram when Amon aquired James’ newspaper. Thanks in advance for your help.

Thanks, David. The Record history is complicated. I once assumed that Phil was Tony’s father. Phil set me straight.

Here is some history:

The family name and newspaper name are just coincidence.

Fort Worth Record and Register 1903 to 1912 (James R. Record was born in 1885.)

Fort Worth Record 1912 to 1925

Fort Worth Record-Telegram 1925 to 1931

Morning Star-Telegram April 1, 1931

James R. Record went to work for the Star in 1907. The Star became the Star-Telegram in 1909.

Brothers Phil and Tony Record were James R. Record’s nephews.

William Capps https://hometownbyhandlebar.com/?p=33087 for years was president of the Record and built the Denver-Record Building (1913), home of the newspaper and the Fort Worth & Denver railroad.