A word to the wise: When a man of the cloth gives you advice about secular matters, take it.

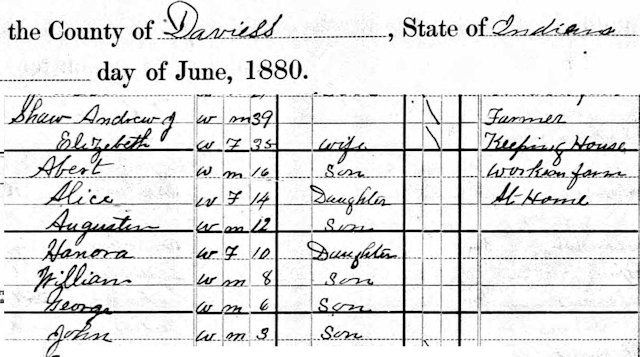

Mrs. Elizabeth Shaw took such advice, and that, as the poet said, made all the difference. In 1889 Mrs. Shaw, age forty-five, widowed with seven children, moved from Indiana to Texas to start a new life because a priest had told her that land was cheap in Texas.

Mrs. Elizabeth Shaw took such advice, and that, as the poet said, made all the difference. In 1889 Mrs. Shaw, age forty-five, widowed with seven children, moved from Indiana to Texas to start a new life because a priest had told her that land was cheap in Texas.

She and her children settled in the countryside south of Fort Worth. But the Shaws didn’t buy any of that cheap Texas land at first. No. They just rented a dairy near where Katy Lake would later be impounded. The dairy’s herd of cows was small; its rolling stock was a single wagon. In the beginning the dairy produced only fourteen gallons a day for twenty-eight customers.

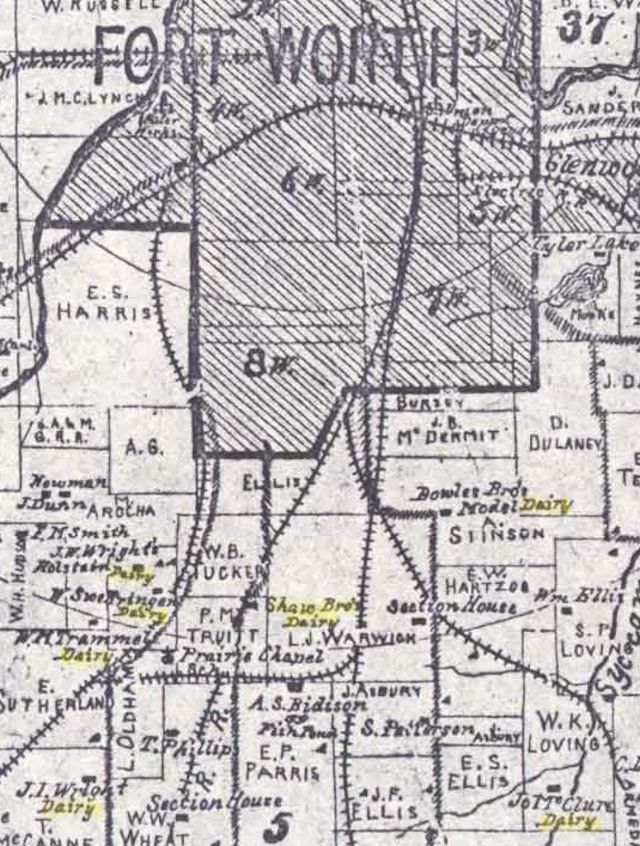

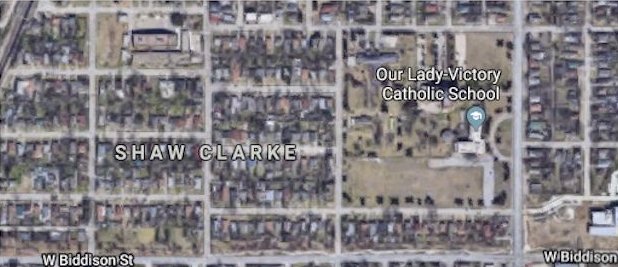

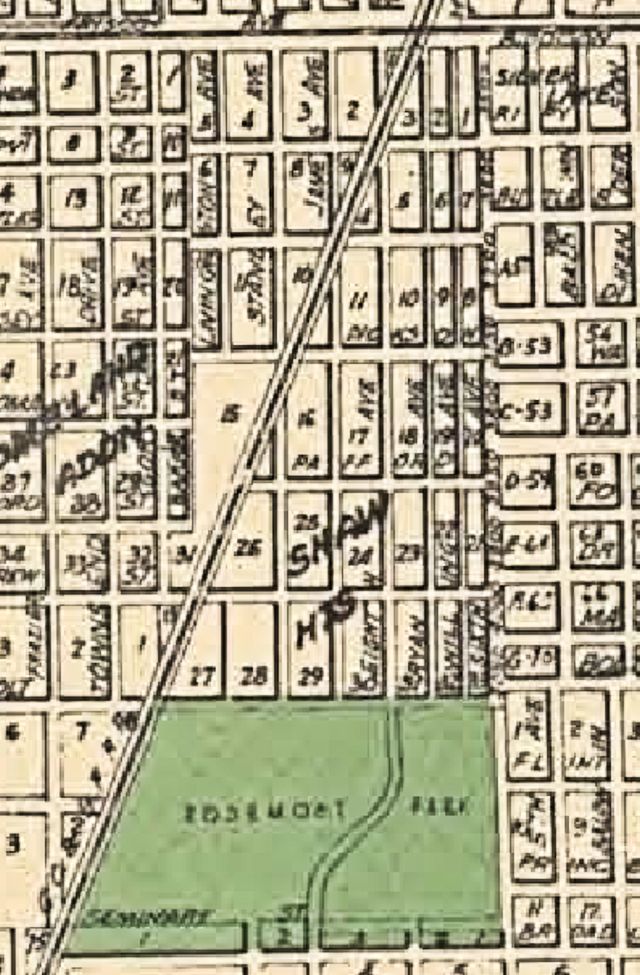

Sometime before 1895 the Shaws began a dairy operation in a new location. This 1895 map shows the Shaw dairy to be about one mile south of the city limits and just north of the belt line railroad track along Biddison Street on today’s South Side. The Shaw dairy had plenty of competition: The countryside just south of Fort Worth by 1895 had seven dairies. No other part of the county had such a concentration of dairies. It was Fort Worth’s Little Wisconsin.

Sometime before 1895 the Shaws began a dairy operation in a new location. This 1895 map shows the Shaw dairy to be about one mile south of the city limits and just north of the belt line railroad track along Biddison Street on today’s South Side. The Shaw dairy had plenty of competition: The countryside just south of Fort Worth by 1895 had seven dairies. No other part of the county had such a concentration of dairies. It was Fort Worth’s Little Wisconsin.

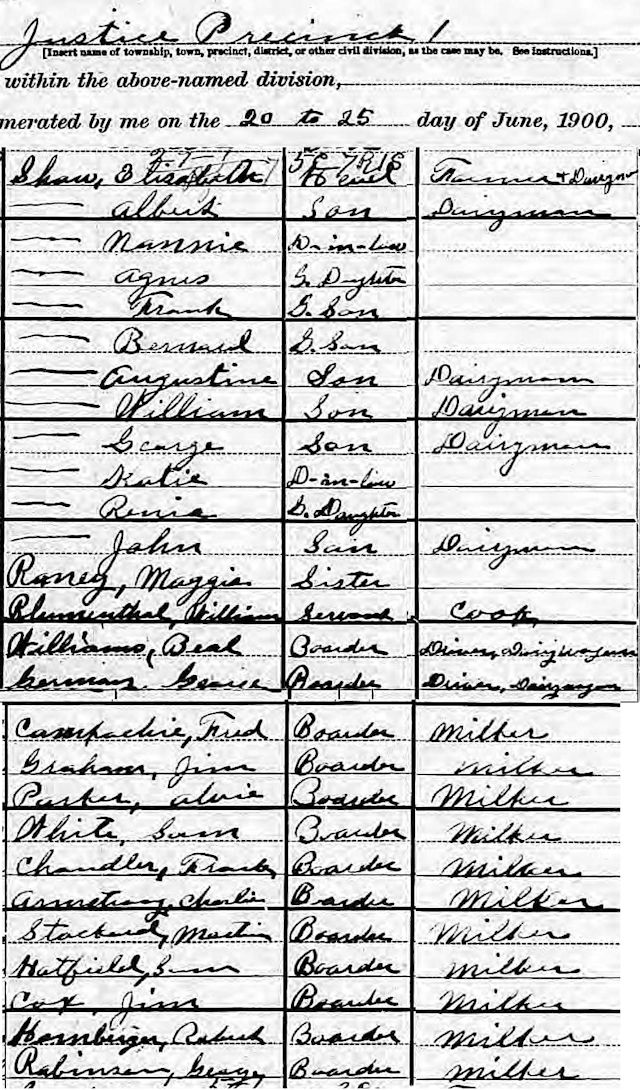

By 1900 Mrs. Shaw was setting an even bigger table: In addition to her extended family, living at the dairy as boarders were workers: a cook, wagon drivers, and milkers.

By 1900 Mrs. Shaw was setting an even bigger table: In addition to her extended family, living at the dairy as boarders were workers: a cook, wagon drivers, and milkers.

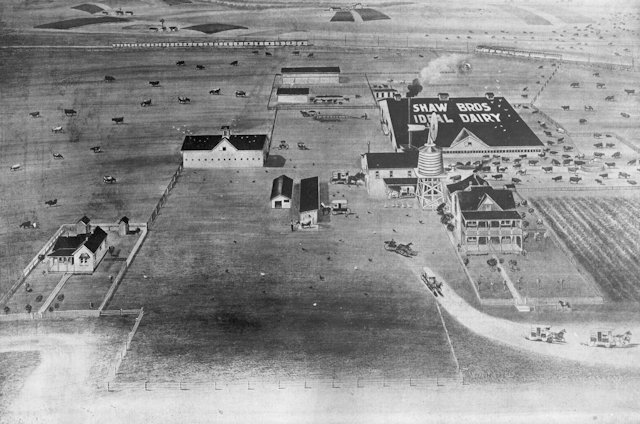

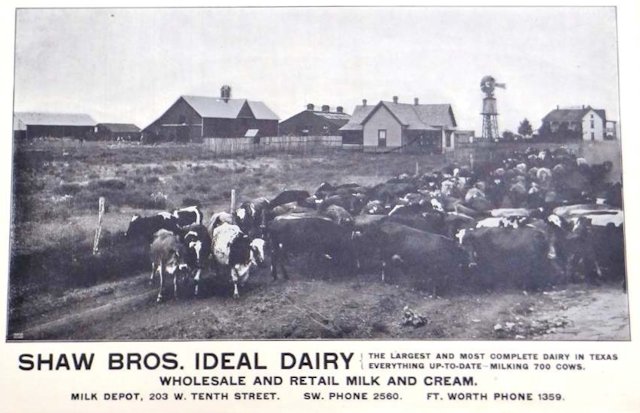

The Shaw brothers—Albert, Gus, John, William, and George—poured their profits back into their dairy and began buying some of that cheap Texas land. More land allowed more cows, which allowed more customers. By 1901 the Shaws had 235 cows producing five hundred gallons of milk a day for six hundred customers. The dairy’s butter churns were powered by steam. The dairy’s artesian well was 420 feet deep, kept a ten thousand-gallon tank filled.

The brothers employed twenty men, worked forty horses.

The Telegram said “agricultural reports” indicated that the Shaw brothers “milk more cows and put out more dairy products than any other dairy in the United States.”

Soon the Shaw business covered two thousand acres, located on several parcels of land as the Shaws “absorbed” a half-dozen smaller dairies in Little Wisconsin and elsewhere: One Shaw parcel was eight miles east of Fort Worth on Village Creek. Eventually the brothers numbered their scattered plots. Shaw dairy no. 1 was north of Echo Lake.

The Shaw dairy. (Photos from the family collections of Doug Sutherland and Billy Joe Gabriel.)

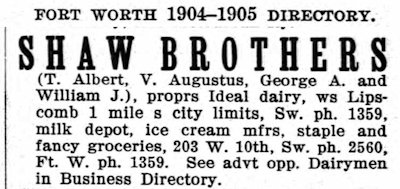

In 1904 the brothers opened a “milk depot” on West 10th Street downtown to sell milk, cream, butter, and ice cream. The city was growing southward: The Shaws’ Ideal Dairy was located on the west side of Lipscomb Street one mile south of the city limits.

In 1904 the brothers opened a “milk depot” on West 10th Street downtown to sell milk, cream, butter, and ice cream. The city was growing southward: The Shaws’ Ideal Dairy was located on the west side of Lipscomb Street one mile south of the city limits.

And the Shaws continued to buy cheap Texas land. In 1905 the Telegram said the dairy now totaled five thousand acres, grazed by 750 cows. Five thousand acres is almost eight square miles—about the size of Little Wisconsin.

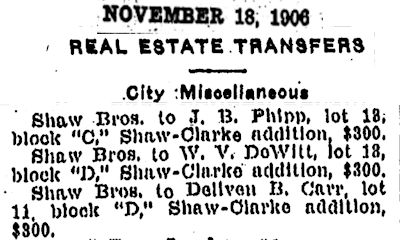

But about 1905 the Shaw brothers apparently decided they needed money for building projects more than they needed that cheap Texas land. They platted part of those five thousand acres and began selling lots. In 1906 they began selling lots in Shaw Clarke addition and in 1907 in Shaw Heights addition.

But about 1905 the Shaw brothers apparently decided they needed money for building projects more than they needed that cheap Texas land. They platted part of those five thousand acres and began selling lots. In 1906 they began selling lots in Shaw Clarke addition and in 1907 in Shaw Heights addition.

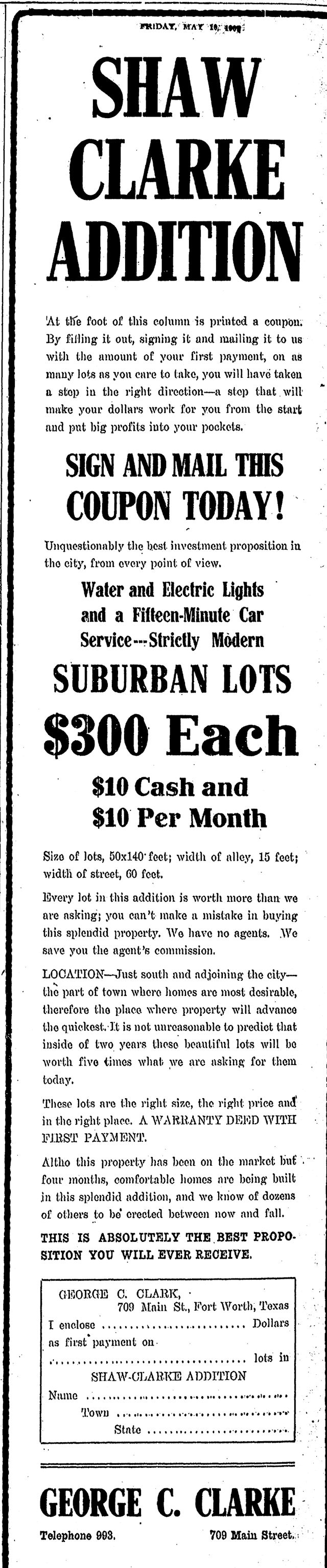

Who was the “Clarke” in “Shaw Clarke”? The Shaw brothers were helped by George Carson Clarke, a major South Side developer, future school board member, and future city parks superintendent. In 1914 the elementary school in Shaw Clarke addition would be named for him. This profile of Clarke published in 1907 points out that the city had just extended the city limits south to the north edge of Shaw Heights (Biddison Street), putting Shaw Clarke to the north within the city.

Who was the “Clarke” in “Shaw Clarke”? The Shaw brothers were helped by George Carson Clarke, a major South Side developer, future school board member, and future city parks superintendent. In 1914 the elementary school in Shaw Clarke addition would be named for him. This profile of Clarke published in 1907 points out that the city had just extended the city limits south to the north edge of Shaw Heights (Biddison Street), putting Shaw Clarke to the north within the city.

Clarke’s ad for Shaw Clarke addition included a coupon. Telegram readers could mail him ten dollars as a down payment. The ad points out that Shaw Clarke was just a fifteen-minute streetcar ride from downtown along Hemphill Street.

Clarke’s ad for Shaw Clarke addition included a coupon. Telegram readers could mail him ten dollars as a down payment. The ad points out that Shaw Clarke was just a fifteen-minute streetcar ride from downtown along Hemphill Street.

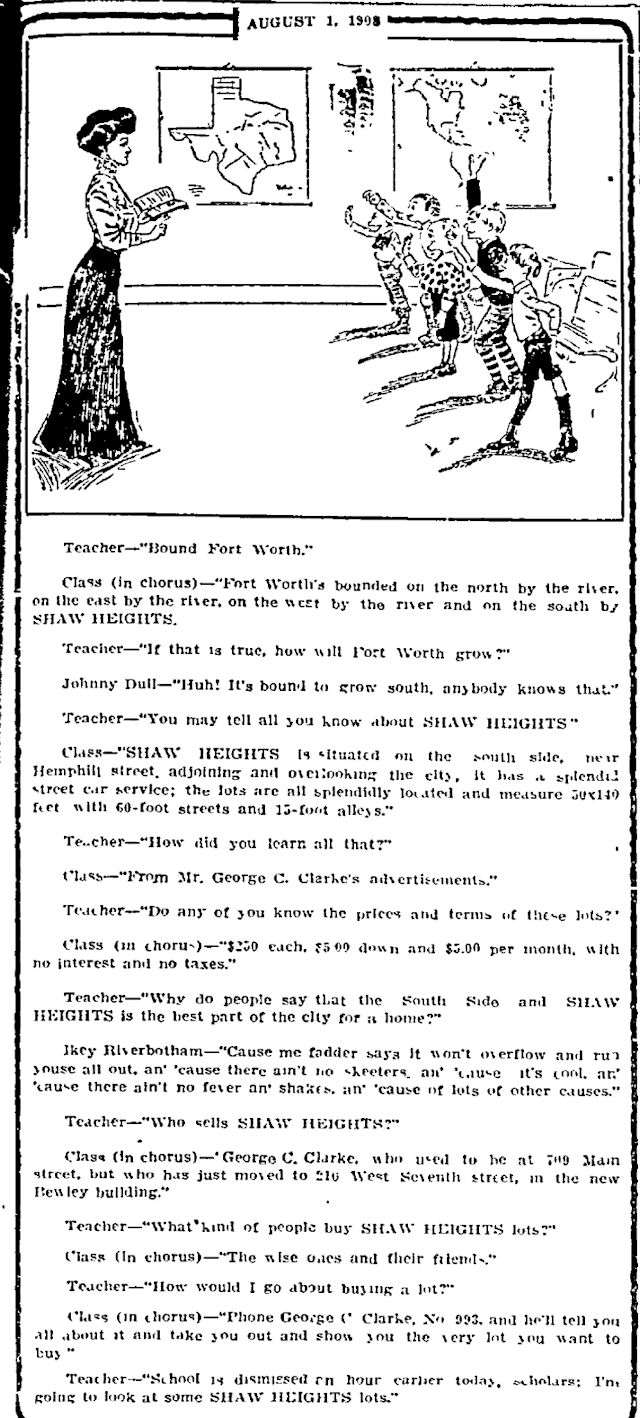

Clarke’s ad for Shaw Heights made the argument that because Fort Worth is “bounded” on the west, north, and east by the Trinity River, the city would expand to the south, making lots in Shaw Heights sure to increase in value.

Clarke’s ad for Shaw Heights made the argument that because Fort Worth is “bounded” on the west, north, and east by the Trinity River, the city would expand to the south, making lots in Shaw Heights sure to increase in value.

One major buyer of land in Shaw Clarke addition in 1908 was St. Ignatius Academy, which bought fifteen acres on which to build Our Lady of Victory Academy.

One major buyer of land in Shaw Clarke addition in 1908 was St. Ignatius Academy, which bought fifteen acres on which to build Our Lady of Victory Academy.

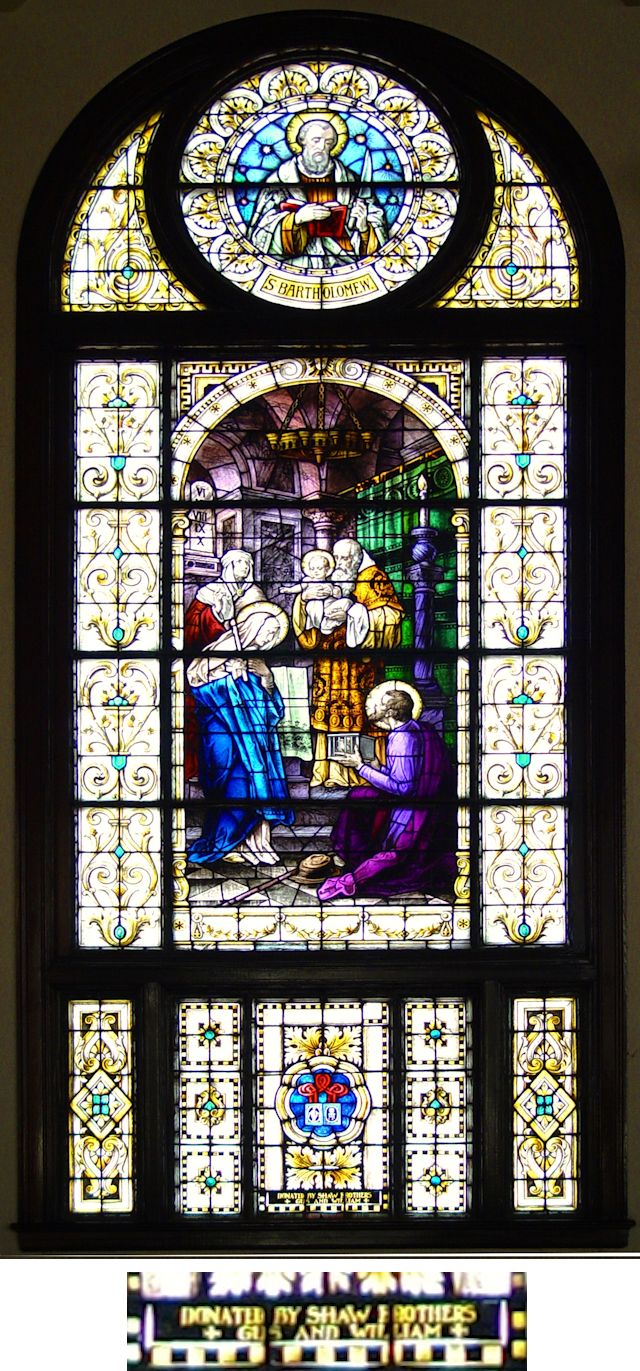

Brothers Gus and William donated this stained glass window to St. Mary of the Assumption Catholic Church on Magnolia Avenue. (Photo from the family collections of Doug Sutherland and Billy Joe Gabriel.)

Brothers Gus and William donated this stained glass window to St. Mary of the Assumption Catholic Church on Magnolia Avenue. (Photo from the family collections of Doug Sutherland and Billy Joe Gabriel.)

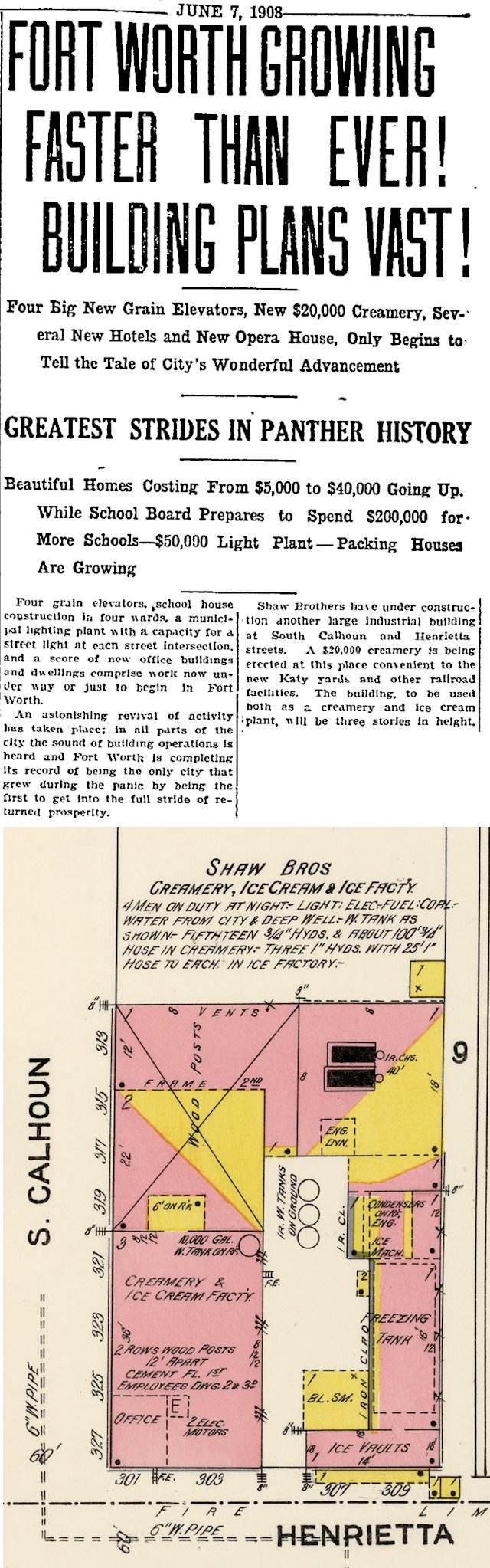

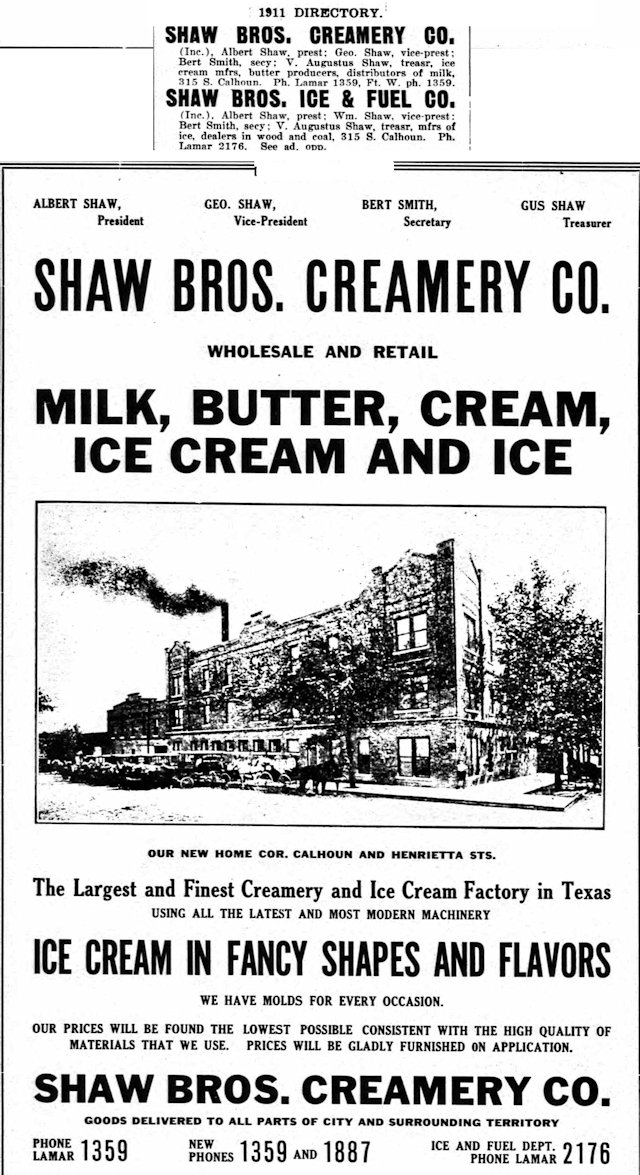

With money coming in now from two cash cows—the dairy and the sale of land—in 1908 the brothers built a three-story brick dairy processing plant on South Calhoun Street. In 1909 they added an ice plant. (That year the Shaw building and the nearby Katy freight depot would survive the South Side fire.)

With money coming in now from two cash cows—the dairy and the sale of land—in 1908 the brothers built a three-story brick dairy processing plant on South Calhoun Street. In 1909 they added an ice plant. (That year the Shaw building and the nearby Katy freight depot would survive the South Side fire.)

The Shaw brothers were men for all seasons: In addition to making and selling ice at their new plant, they sold firewood and coal.

The Shaw brothers were men for all seasons: In addition to making and selling ice at their new plant, they sold firewood and coal.

In fact, the brothers formed a separate company for ice and fuel.

In fact, the brothers formed a separate company for ice and fuel.

They also sold manure-rich “dairy loam” to gardeners.

In 1909 the Star-Telegram said the Shaw dairy was the world’s largest, employing 125 people, 1,200 cows producing 1,500 gallons of milk and 650 pounds of butter a day.

In 1909 the Star-Telegram said the Shaw dairy was the world’s largest, employing 125 people, 1,200 cows producing 1,500 gallons of milk and 650 pounds of butter a day.

From land to loam, from cream to coal, the Shaw brothers had become the lords of Little Wisconsin.

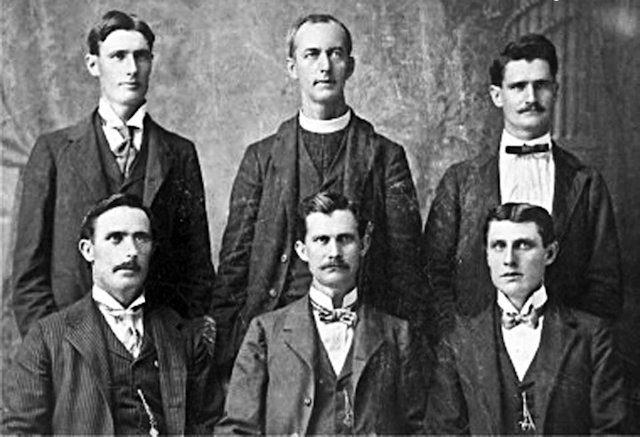

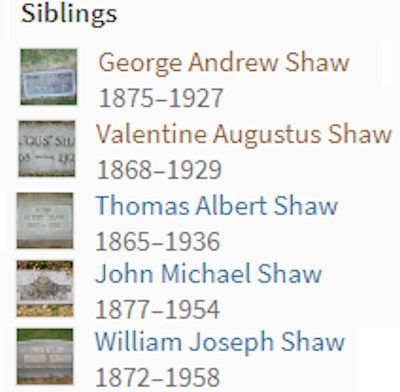

Five brothers and a father: Top from left: George Andrew, Father Patrick of the Catholic church, John Michael; bottom from left: William Joseph, Thomas Albert, Valentine Augustine. (Photo from the family collections of Doug Sutherland and Billy Joe Gabriel.)

Five brothers and a father: Top from left: George Andrew, Father Patrick of the Catholic church, John Michael; bottom from left: William Joseph, Thomas Albert, Valentine Augustine. (Photo from the family collections of Doug Sutherland and Billy Joe Gabriel.)

Matriarch Elizabeth Shaw and sons George Andrew, John Michael, William Joseph, Thomas Albert, and Valentine Augustine and daughters Alice and Hanora in 1918. (Photo from the family collections of Doug Sutherland and Billy Joe Gabriel.)

The Shaw plant on South Calhoun Street and its delivery fleet. (Photos from the family collections of Doug Sutherland and Billy Joe Gabriel.)

The Shaw plant on South Calhoun Street and its delivery fleet. (Photos from the family collections of Doug Sutherland and Billy Joe Gabriel.)

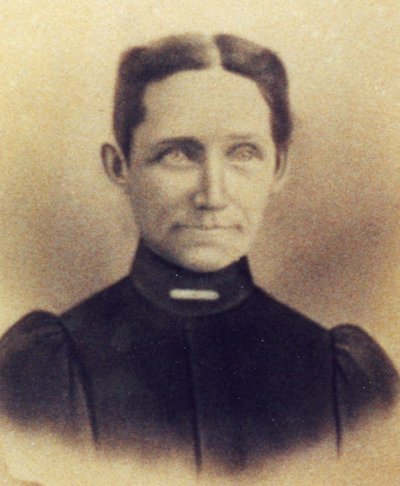

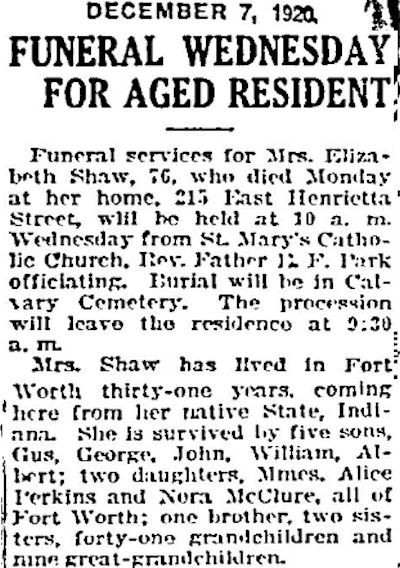

But the success of the dairy was overshadowed in 1920 when the Shaw children lost their mother, whose decision to take a priest’s advice thirty-one years earlier had brought them to Texas. (Photo from the family collections of Doug Sutherland and Billy Joe Gabriel.)

But the success of the dairy was overshadowed in 1920 when the Shaw children lost their mother, whose decision to take a priest’s advice thirty-one years earlier had brought them to Texas. (Photo from the family collections of Doug Sutherland and Billy Joe Gabriel.)

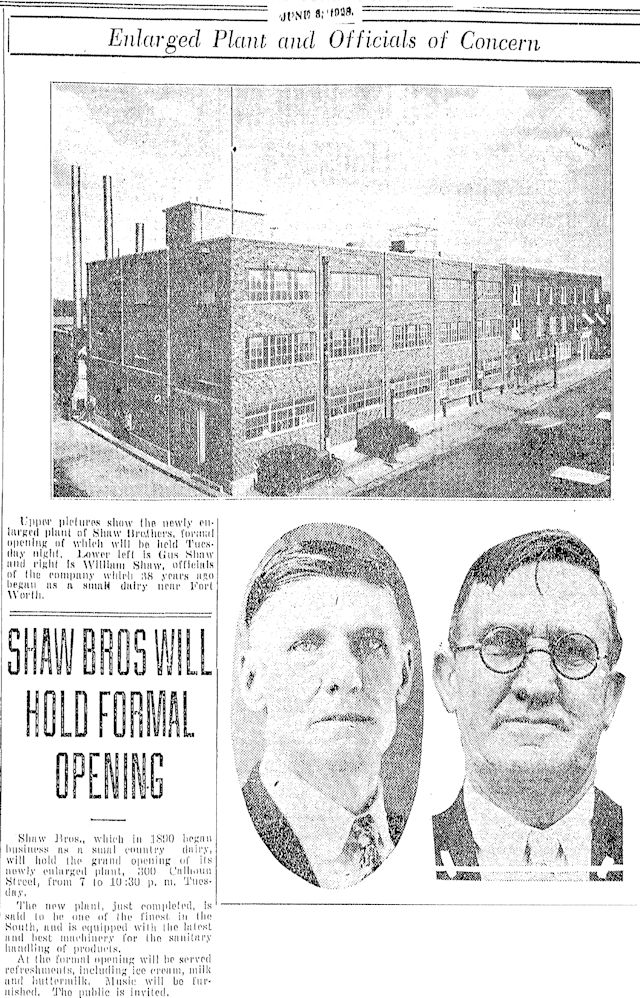

In 1928 the brothers built a three-story addition to the 1908 plant and modernized the existing building. Now the plant could produce eight thousand gallons of milk a day, 1,350 pounds of butter, 2,700 gallons of ice cream. The ice plant could produce ninety tons of ice a day and store 2,300 tons in the ice vault.

In 1928 the brothers built a three-story addition to the 1908 plant and modernized the existing building. Now the plant could produce eight thousand gallons of milk a day, 1,350 pounds of butter, 2,700 gallons of ice cream. The ice plant could produce ninety tons of ice a day and store 2,300 tons in the ice vault.

The dairy employed two hundred people and operated seventy-five teams of horses and mules and a fleet of fifty motor vehicles.

But by 1928 only brothers Gus and William remained as officers of the company.

At the grand opening of the new plant, guests were served—what else?—ice cream, milk, and buttermilk.

As an indication of agriculture’s importance to the local economy, in 1929 the Star-Telegram published an entire section devoted to the dairy and poultry industries.

As an indication of agriculture’s importance to the local economy, in 1929 the Star-Telegram published an entire section devoted to the dairy and poultry industries.

Also in 1929 the Shaws’ Ideal Dairy became part of Southwest Dairy Products Company, which owned dairies in Texas and Louisiana.

Also in 1929 the Shaws’ Ideal Dairy became part of Southwest Dairy Products Company, which owned dairies in Texas and Louisiana.

In fact, in 1933 Southwest Dairy Products moved its headquarters to the Shaw building on South Calhoun Street. The Shaw brothers were no longer listed among the officers of the Shaw dairy or its parent company.

In fact, in 1933 Southwest Dairy Products moved its headquarters to the Shaw building on South Calhoun Street. The Shaw brothers were no longer listed among the officers of the Shaw dairy or its parent company.

And by 1935 the name “Shaw” no longer was listed among dairies in the city directory.

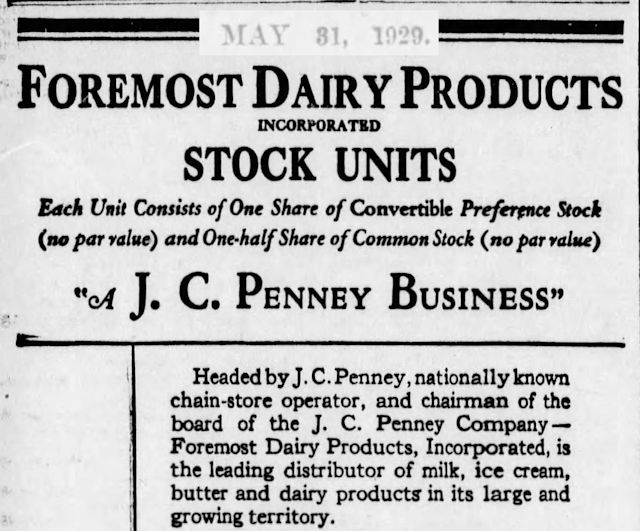

In 1945 the gobbler became the gobbled: Foremost Dairies bought controlling interest in Southwest Dairy Products.

In 1945 the gobbler became the gobbled: Foremost Dairies bought controlling interest in Southwest Dairy Products.

Foremost had been founded by J. C. Penney.

Foremost had been founded by J. C. Penney.

Today the five Shaw brothers, their dairy, and the rest of Fort Worth’s Little Wisconsin are gone, all that cheap Texas land now covered by the homes and shops and streets of the South Side. The Shaw buildings of 1908 and 1928 on South Calhoun Street were torn down in the 1980s.

Today the five Shaw brothers, their dairy, and the rest of Fort Worth’s Little Wisconsin are gone, all that cheap Texas land now covered by the homes and shops and streets of the South Side. The Shaw buildings of 1908 and 1928 on South Calhoun Street were torn down in the 1980s.

But today street signs remind us of a chapter in South Side history: Shaw Street passes in front of OLV and George C. Clarke Elementary School in Shaw Clarke addition.

But today street signs remind us of a chapter in South Side history: Shaw Street passes in front of OLV and George C. Clarke Elementary School in Shaw Clarke addition.

And in Capps Park on West Berry Street a bench is dedicated to the memory of one of the lords of Little Wisconsin.

And in Capps Park on West Berry Street a bench is dedicated to the memory of one of the lords of Little Wisconsin.

(Thanks to Shaw descendants William Joseph Gabriel and Doug Sutherland for their help.)

William Joseph Shaw IV here. Just wanted to say thanks for a great read. Like my brother I should probably pick Doug’s brain at some point. For now I’ll be headed to the church on magnolia to see the stained glass donated by my namesake. Really a great write up. Thanks.

Thanks. I had a lot of help from members of this dynamic Fort Worth family.

Well that was a fun read. I knew there was a dairy and I even have an old “Notice of Sale” posted by Elizabeth Shaw for all of her goods in Indiana that she wasn’t taking to Texas, but I never knew this much back story. Suppose I could have asked Doug one year at Christmas, but never did. Any other Shaws reading this and going “How is our family not loaded???” Maybe that’s just me. Fun fact, there is a William Joseph III and a William Joseph IV, both still in the FW area.

Thanks, Andrew. Billy Joe and Doug were a big help to me in my research.

I have a old metal shaw bros milk jug. It says shaw bros 26

Thanks for the history lesson, gentlemen.

Thanks. I enjoyed learning the Shaw story.

Mike, Great story. Your research is terrific. I learned about my family from your article.

My Great Grandmother on my Mother’s side was Alice Shaw Perkins. She was one of the 2 sisters to the 5 Shaw Brothers. Always had plenty of cousins in the Southside for special events, family parties, and the holidays. It took a lot of us to milk all the cattle.

Thanks to you and Doug for the info and photos. Bet the cows appreciated warm hands on a day like today.

Mike, Have recently verified the reason Albert left ShawBros and moved to Jacksonville OR (Medford) was so that he could raise his family without payouts to th Ku Klux Klan to protect property and family. All of his (Albert’s) descendents still reside in Oregon and California.

Thanks, Doug. I ran across one mention of the KKK in my Shaw research-a descendant recalling the Klan’s anti-Catholicism.

I am Alberts great great grandson. I was actually looking all of this up because I’ve always heard the KKK story and I was hoping for some record of it. A police report or something. Regardless this was very fun to read about, thank you.