In the 1950s, at the height of Fort Worth’s gangland violence, some observers with a long memory said the very first gangland slaying in town had taken place in 1944 on a quiet street in Arlington Heights.

And appropriate for the city “where the West begins,” the victim was a cowboy.

Louis Cleo Tindall was born the son of Jack Tindall, a riding school master who himself had once been a cowboy on the open range. Jack Tindall was said to have carried his “roll” (as much as $10,000) in one boot and a six-gun in the other.

Louis learned his way around a horse at an early age from his father. By his early twenties Louis was a professional trick rider, performing at Fort Worth’s stock show and rodeo.

Louis learned his way around a horse at an early age from his father. By his early twenties Louis was a professional trick rider, performing at Fort Worth’s stock show and rodeo.

In 1925 Louis married another trick rider, Velda Callahan. They had met while performing at Fort Worth’s stock show and rodeo.

In 1925 Louis married another trick rider, Velda Callahan. They had met while performing at Fort Worth’s stock show and rodeo.

Louis and Velda toured the country in their Packard, performing at rodeos in Boston, Cheyenne, Salt Lake City, Chicago. Tindall would ride around an arena while standing Roman style atop two horses. For the climax he would ride the two horses as they jumped over the Packard.

Louis and Velda toured the country in their Packard, performing at rodeos in Boston, Cheyenne, Salt Lake City, Chicago. Tindall would ride around an arena while standing Roman style atop two horses. For the climax he would ride the two horses as they jumped over the Packard.

Years later Velda recalled: “Louis’s most famous trick was the one where he’d go between the horse’s back legs while it was running full gallop. He’d just go right down over the back of the horse, over the tail and right through the back legs, then come back up from the stomach. He also did a trick where he’d stand with one foot next to the saddle horn and one between the horse’s ears. The key was the horse, and Louis had the only horse that’d let you do that trick. There just aren’t many horses that’ll let you go between their back legs. Most of them get spooked.”

The Tindalls often appeared on the same bill with two other rodeo stars from Fort Worth—Buck and Tad Lucas.

The Tindalls often appeared on the same bill with two other rodeo stars from Fort Worth—Buck and Tad Lucas.

Some of the horses Louis performed on were trained by the Lucases.

Some of the horses Louis performed on were trained by the Lucases.

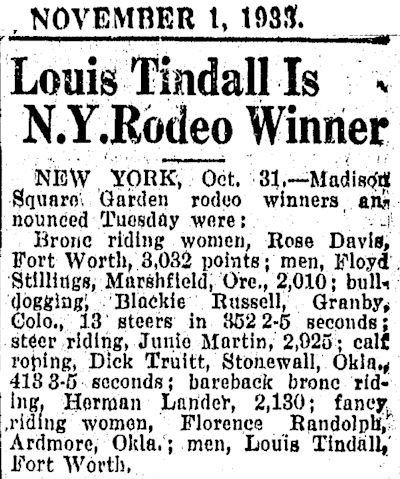

The Tindalls performed at Madison Square Garden every year for a decade.

The Tindalls performed at Madison Square Garden every year for a decade.

At this point, cowboys and cowgirls, y’all best grab the reins and hold on tight. The life of Louis Cleo Tindall is about to start bucking like a bronc.

At this point, cowboys and cowgirls, y’all best grab the reins and hold on tight. The life of Louis Cleo Tindall is about to start bucking like a bronc.

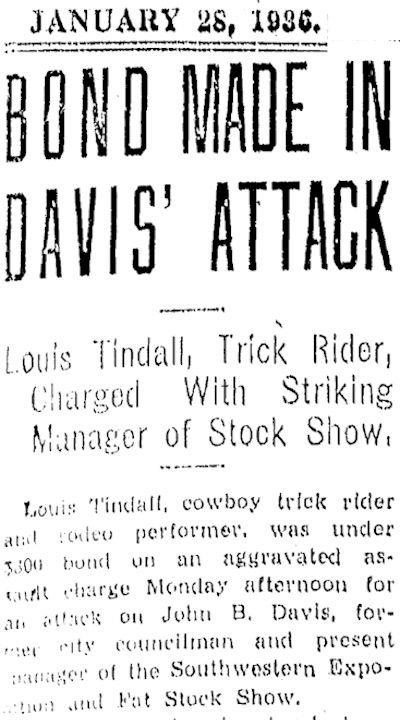

In 1936 Louis Tindall’s name began to appear in parts of the newspaper besides the sports section. He was charged with aggravated assault after beating John B. Davis, manager of the Fort Worth stock show and rodeo and a former city councilman. The attack took place near the stockyards. Tindall told newspapers he was merely fulfilling a promise: “I told him I’d whip him the first time I caught him on the avenue. What’s more, my promise is still good. Next time I find him there I’ll whip him again. Why, I could whip him with my right hand tied behind me.”

In 1936 Louis Tindall’s name began to appear in parts of the newspaper besides the sports section. He was charged with aggravated assault after beating John B. Davis, manager of the Fort Worth stock show and rodeo and a former city councilman. The attack took place near the stockyards. Tindall told newspapers he was merely fulfilling a promise: “I told him I’d whip him the first time I caught him on the avenue. What’s more, my promise is still good. Next time I find him there I’ll whip him again. Why, I could whip him with my right hand tied behind me.”

Why the animosity? Tindall said Davis had refused to let Tindall compete in the rodeo the last two years.

“I was good enough for Madison Square Garden. And I was good enough to double for Bing Crosby in a western picture [probably Rhythm on the Range] that will be released soon. But Davis didn’t think I was good enough for Fort Worth.”

Tindall was found guilty.

Tindall was found guilty.

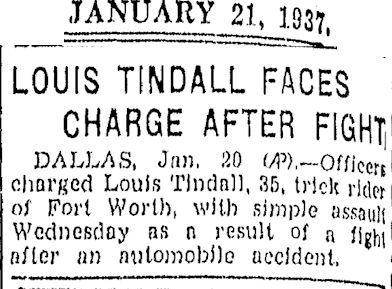

And the next year Tindall was charged with simple assault after a fight in Dallas.

And the next year Tindall was charged with simple assault after a fight in Dallas.

Violence aside, the show went on. By 1939 Louis and Velda were still appearing on the same bill with Tad Lucas. And now Louis and Velda’s act included two children: two daughters. And notice the name “George Wilderspin.” We’ll come back to him.

Violence aside, the show went on. By 1939 Louis and Velda were still appearing on the same bill with Tad Lucas. And now Louis and Velda’s act included two children: two daughters. And notice the name “George Wilderspin.” We’ll come back to him.

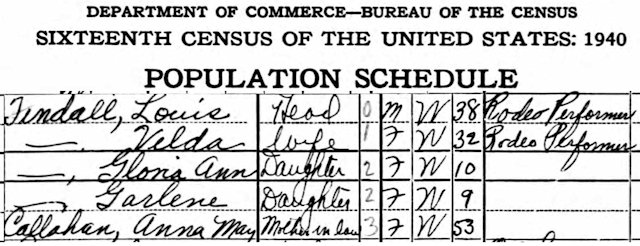

In 1940 the trick-riding Tindalls shared their home with Velda’s mother, Anna May Callahan. We’ll come back to her.

In 1940 the trick-riding Tindalls shared their home with Velda’s mother, Anna May Callahan. We’ll come back to her.

By 1941 Louis Tindall, after holding the title of world’s champion trick rider for several years, was a former trick rider. He also was on his way to becoming a former husband. Velda Callahan Tindall was divorcing him because he had begun stepping out with Opal Boyer. Velda threw him out of the house. He came back, she claimed, destroyed the furnishings, tore up her clothes, withdrew $1,800 from their bank account, took $500 in cash, a diamond bracelet, and an automobile from her, brandished two guns, and attacked her mother, holding Mrs. Callahan prisoner and beating her with a pistol and a Bible. Mrs. Callahan suffered a broken arm.

Tindall was charged with assault to murder.

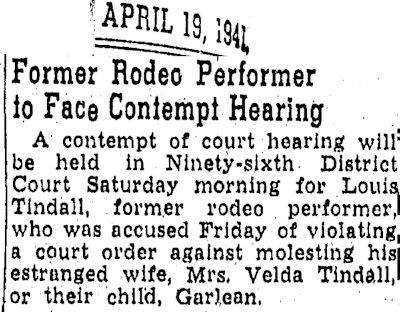

Velda went to court and got a restraining order issued against Tindall. He was charged with violating that order.

Velda went to court and got a restraining order issued against Tindall. He was charged with violating that order.

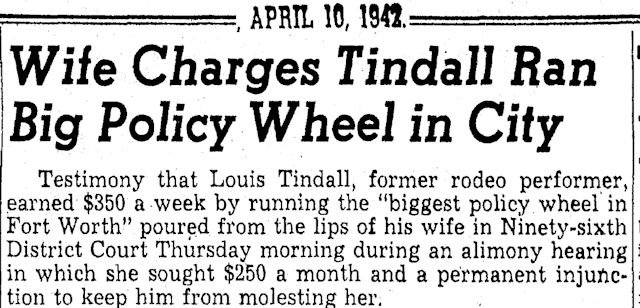

Velda filed for divorce and sought $250 ($3,900 today) a month in alimony from Louis. At a hearing to set the amount of alimony, she let the bronc out of the stall: She told the judge that Tindall was running “the biggest policy wheel in Fort Worth.”

Velda filed for divorce and sought $250 ($3,900 today) a month in alimony from Louis. At a hearing to set the amount of alimony, she let the bronc out of the stall: She told the judge that Tindall was running “the biggest policy wheel in Fort Worth.”

(A policy wheel—or “policy game” or “numbers racket”—is a form of illegal gambling in which a bettor attempts to pick three numbers to match numbers that will be randomly drawn the following day. Gamblers place bets with a bookmaker. The term policy derives from the game’s resemblance to insurance, which is also a gamble on the future.)

Velda told the judge that she had seen her husband’s “book” and that he raked in $350 a month “clear profit” on the policy game and had no legal income. The judge, no doubt rolling his eyes, told her, the Star-Telegram reported, “I want it definitely understood that I can’t allow a man to run a policy game to pay alimony, and I just won’t have it at all.”

Louis denied everything, said he had only $49 to his name and no income “legal or illegal.”

Velda was granted her divorce from Louis, a permanent restraining order to prevent him from “molesting” her, and $150 a month alimony.

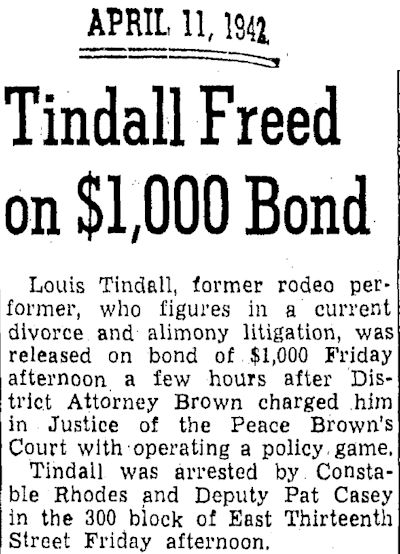

Tindall was immediately arrested and charged with operating a policy game.

Tindall was immediately arrested and charged with operating a policy game.

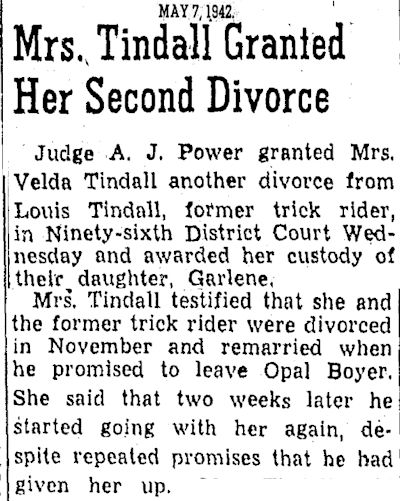

Louis did not have to pay alimony long. Soon after the divorce, Louis promised to stop seeing Opal, and Velda remarried him. But two weeks later he was seeing Opal again, so Velda divorced him a second time.

Louis did not have to pay alimony long. Soon after the divorce, Louis promised to stop seeing Opal, and Velda remarried him. But two weeks later he was seeing Opal again, so Velda divorced him a second time.

Then Louis married Opal.

(Hold tight to those reins, cowboys and cowgirls.)

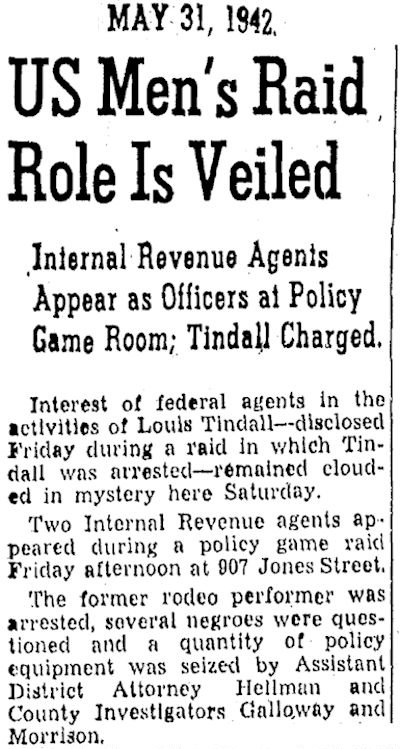

Then Tindall was arrested again when the district attorney’s office, with Internal Revenue agents looking on, raided his policy game room behind a barber shop at 907 Jones Street. Now he faced two charges of illegal gambling.

Then Tindall was arrested again when the district attorney’s office, with Internal Revenue agents looking on, raided his policy game room behind a barber shop at 907 Jones Street. Now he faced two charges of illegal gambling.

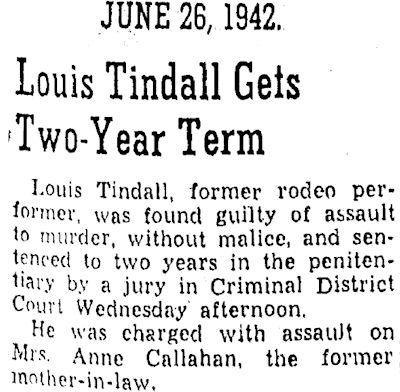

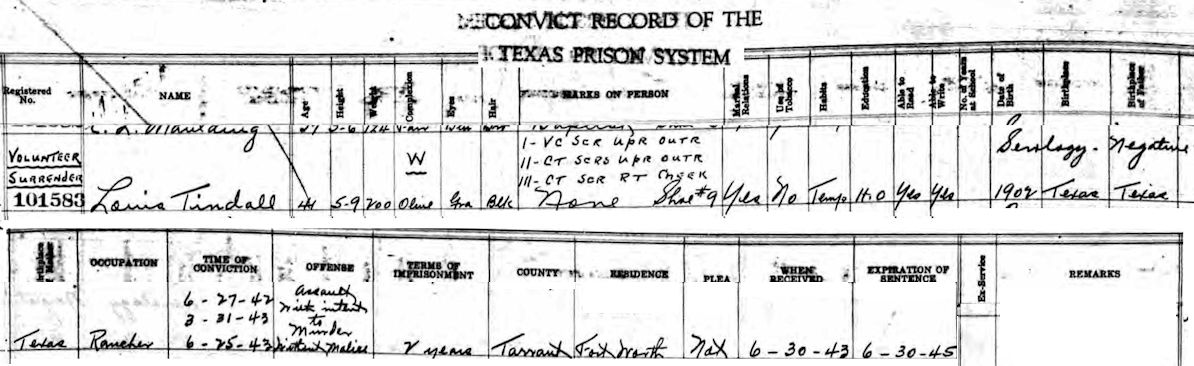

Three days later he was convicted of assault to murder and sentenced to two years in prison.

Three days later he was convicted of assault to murder and sentenced to two years in prison.

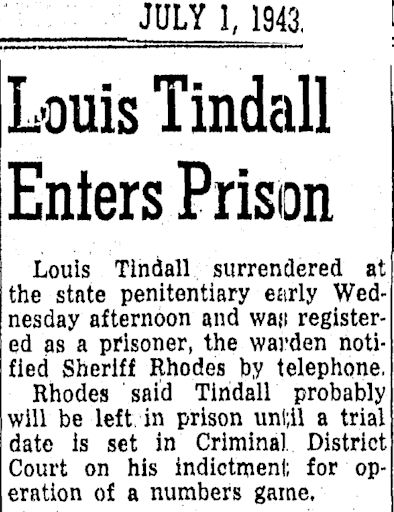

A year later, on June 30, 1943, Louis Tindall reported to Huntsville. He still had not been tried for the two policy game charges.

A year later, on June 30, 1943, Louis Tindall reported to Huntsville. He still had not been tried for the two policy game charges.

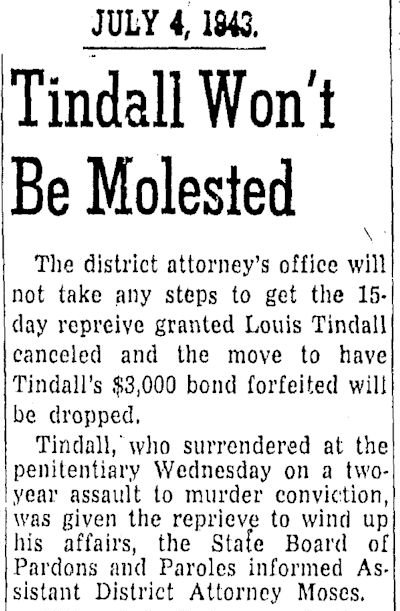

But Tindall was in prison only a few days before he was granted a reprieve to settle business affairs.

But Tindall was in prison only a few days before he was granted a reprieve to settle business affairs.

Fast-forward to 1944. Tindall was still a free man. He had been granted another reprieve to procure medical care for his daughter Garlene, who had contracted polio.

Louis Tindall would have been better off in prison.

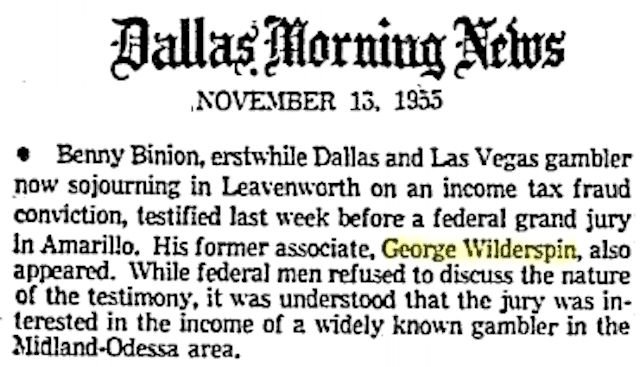

Tindall’s conduit from rodeos to rackets was George Wilderspin. Like Tindall, Wilderspin was a rodeo performer—a champion calf roper. He also was an associate of Dallas gambler Benny Binion, who later would operate Binion’s Horseshoe casino in Las Vegas and go to prison for income tax evasion.

Wilderspin first did business with Binion in cattle and then partnered with Binion in the East Side Club in Haltom City.

Doug Swanson in Blood Aces: The Wild Ride of Benny Binion, The Texas Gangster Who Created Las Vegas Poker writes that Binion hired Wilderspin to oversee the gambling room of the East Side Club and that Wilderspin in turn hired Tindall to run some of their lesser Fort Worth gambling endeavors.

Police would question Wilderspin after the Nelson Harris car-bombing in 1950. He also would be among big-time gamblers arrested in a dragnet in 1951 that resulted from the Harris car-bombing.

Police would question Wilderspin after the Nelson Harris car-bombing in 1950. He also would be among big-time gamblers arrested in a dragnet in 1951 that resulted from the Harris car-bombing.

Binion and “his former associate, George Wilderspin” would testify before a grand jury about gambling in 1955.

Binion and “his former associate, George Wilderspin” would testify before a grand jury about gambling in 1955.

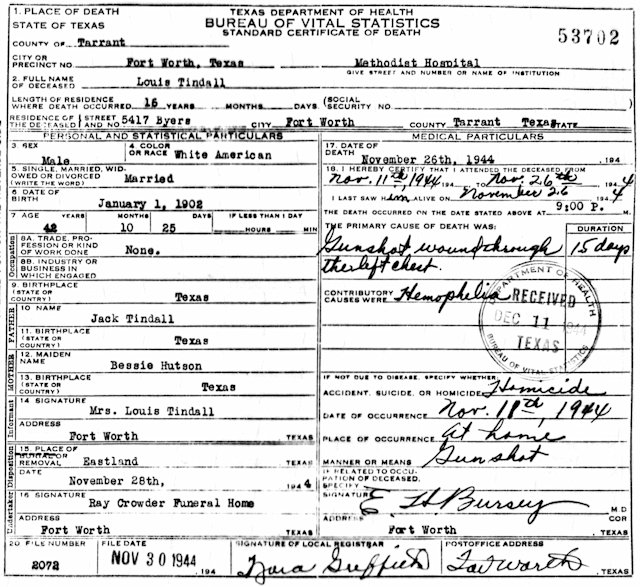

A gambler is, by definition, a risk-taker. The fact that Louis Tindall had been a trick rider showed that he was willing to take risks. An illegal gambler also can’t be timid. Tindall’s propensity for violence showed that he was not timid. But Louis Tindall had one trait that made him ill suited for the violent life of an illegal gambler:

He was a hemophiliac.

And beginning on November 12, 1944, for the next quarter of a century illegal gambling in Fort Worth would be a blood sport.

Illegal gambling of that era was a brutal business. When gamblers felt they had been wronged by another gambler, they did not file complaints with police. They filed bullets and car-bombs.

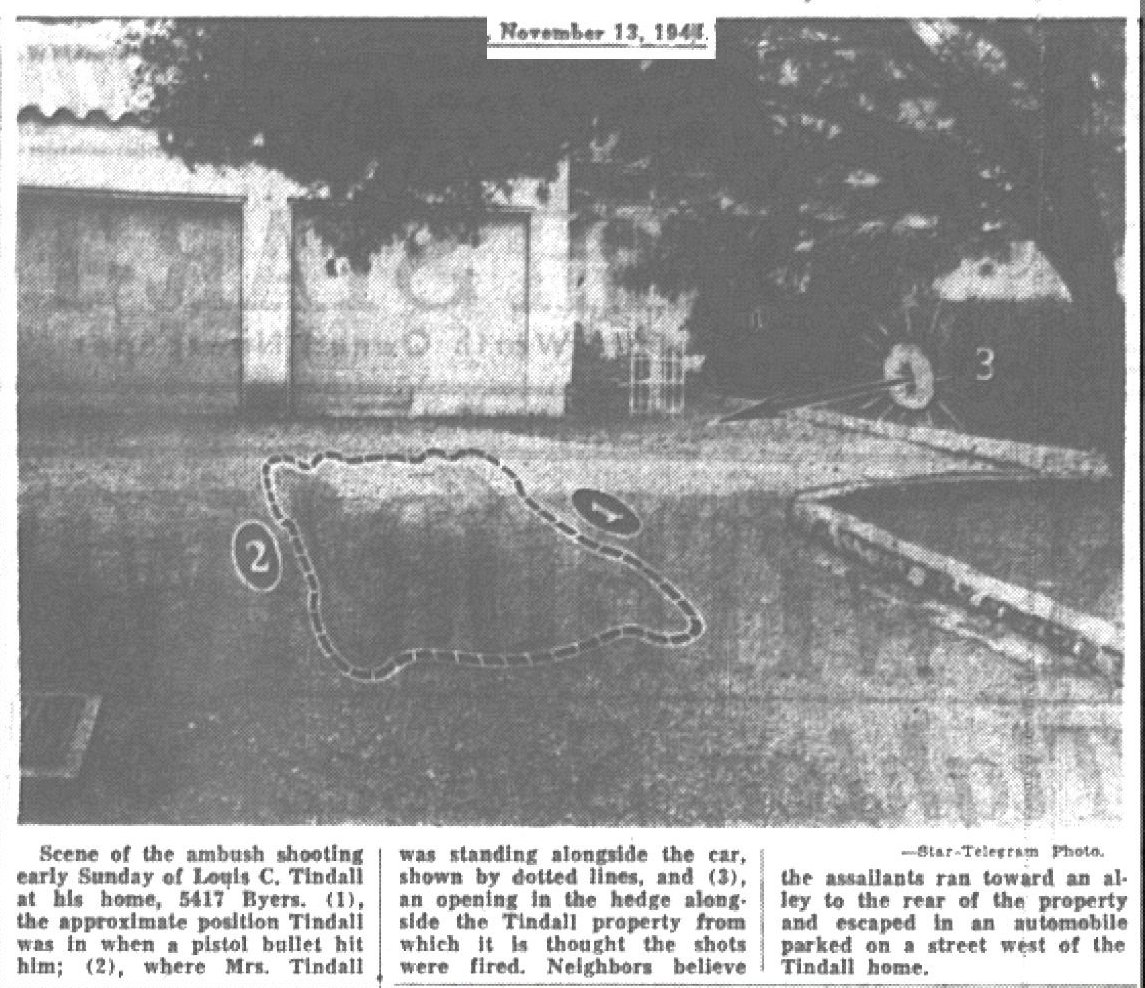

At 1 a.m. November 12, 1944 Louis and Opal Tindall returned to their home at 5417 Byers Avenue in Arlington Heights after seeing a movie downtown. Tindall had begun to fear for his life, so Opal always drove the Cadillac so that he could “keep lookout,” she later said. She said she and her husband always carried .44-caliber pistols at night. And when they arrived home she always went into the house first to be sure it was safe before he came in.

And so it was on this night. As Opal got out of the Cadillac to go check the house, a floodlight illuminated the driveway.

Before she got to the house a shotgun blast came from behind a nearby hedge.

Opal later said: “I had my gun in my hand, and Louis thought I was shooting at him. I started to tell him I hadn’t fired, and as he turned around toward me a second [gunshot] hit him in the back. He said ‘Duck, Honey,’ and I did.”

She warned Tindall to get behind the car.

The shotgun blast had missed Tindall by about a foot.

The second shot, from a pistol, hit Tindall in the right side.

A third shot ripped through his pocket but missed him.

Husband and wife emptied their pistols at the hedge where the shots had come from.

Two assailants escaped through an alley.

Opal then drove Louis to the hospital.

“It’s hell to go through life not knowing when you’re going to be shot,” Opal Tindall later said.

“It’s hell to go through life not knowing when you’re going to be shot,” Opal Tindall later said.

Tindall always carried a lot of cash—profit from the policy racket. But he told police he thought the ambush was an attempted assassination, not an attempted robbery. But he said he did not know who his assailants were.

The house at 5417 Byers Avenue today.

The house at 5417 Byers Avenue today.

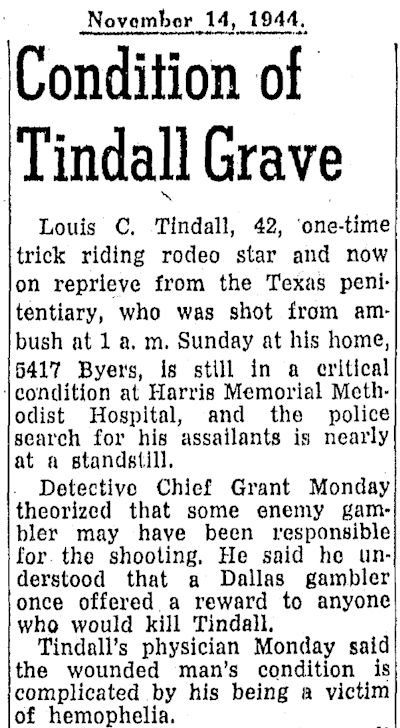

Police speculated that Tindall had made an enemy over a policy racket in Dallas and that he had a price on his head. Fort Worth police chief detective Howard Grant said, “Robbery was not the motive of the shooting. For some time Tindall had been living in the fear that an attempt would be made to take his life. His trouble with an enemy gambler dates back to a policy game in Dallas several years ago. Tindall once said that a Dallas gambler had offered $5,000 to anyone who would kill him.”

Police speculated that Tindall had made an enemy over a policy racket in Dallas and that he had a price on his head. Fort Worth police chief detective Howard Grant said, “Robbery was not the motive of the shooting. For some time Tindall had been living in the fear that an attempt would be made to take his life. His trouble with an enemy gambler dates back to a policy game in Dallas several years ago. Tindall once said that a Dallas gambler had offered $5,000 to anyone who would kill him.”

Louis Tindall’s condition was too precarious for police to question him in much detail.

Louis Tindall’s condition was too precarious for police to question him in much detail.

Doctors gave him a lot of blood as they fought on two fronts—a gunshot wound and hemophilia.

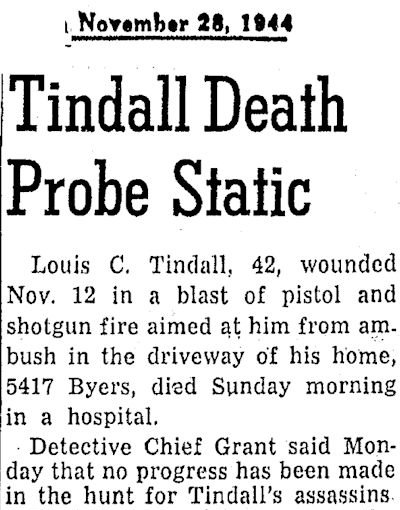

Tindall died on November 26. Police reported no progress in their investigation of the shooting.

Tindall died on November 26. Police reported no progress in their investigation of the shooting.

So. Who ambushed Louis Tindall?

So. Who ambushed Louis Tindall?

Ann Arnold in Gamblers & Gangsters writes: “Word on the underground grapevine was that Benny Binion wanted to move into Fort Worth’s policy racket and that Tindall, the local boss, opposed him. Binion supposedly put out a contract, but police had no clue as to the identity of the man.”

(Doug Swanson in Blood Aces writes that in 1936 Binion and a colleague had shot to death a competing policy racket operator. Binion then allegedly shot himself in the shoulder and turned himself in to police, claiming that the policy racket operator had shot him first. Binion was indicted, but the indictment was dropped on the grounds that Binion had acted in self-defense.)

Louis Tindall, world champion trick rider-turned-gambler, is buried in Eastland County.

Louis Tindall, world champion trick rider-turned-gambler, is buried in Eastland County.

Fort Worth’s first gangland slaying was never solved.

Posts About Crime Indexed by Decade

My grandparents Buck and Tad Lucas sold Louis & Velda a corner lot that was part of their homestead at 909 Roberts Cut-Off Rd - Velda Tindall & Faye Kirkwood ( W C “Kirk” Kirkwood’s wife) were two of Tad’s best friends - would enjoy visiting with you about this part of Fort Worth’s history…

Thanks, Kelly. I have a post on Tad coming. Also will include her in a post on Rose Hill Cemetery.