It’s a heartwarming Christmas story that has all the traditional yuletide elements:

One jealous preacher

One one-legged man named “Napoleon”

One cheap handgun

One homicide

Our story begins at this house at 1109 East Broadway Street.

Our story begins at this house at 1109 East Broadway Street.

In 1933 the house belonged to Willis Napoleon Shaw.

In 1933 the house belonged to Willis Napoleon Shaw.

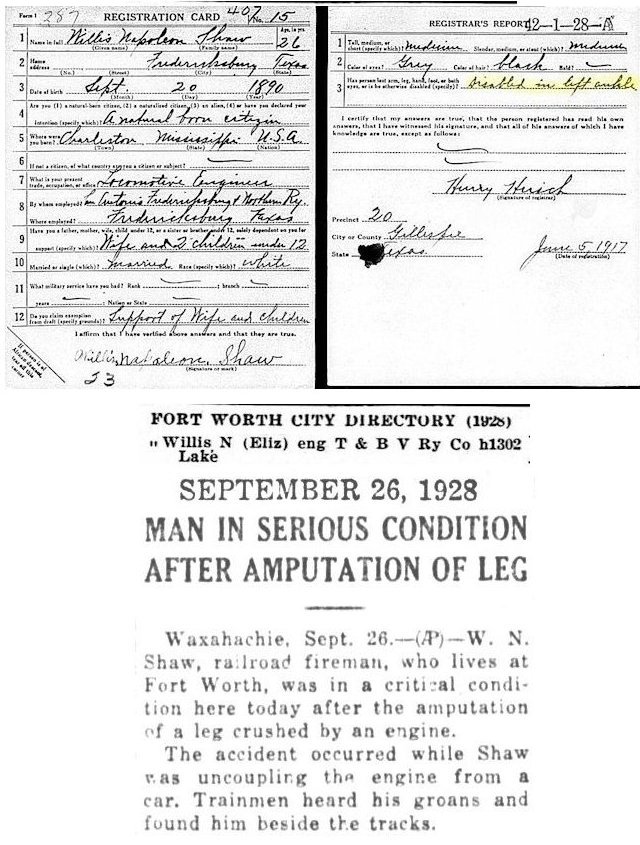

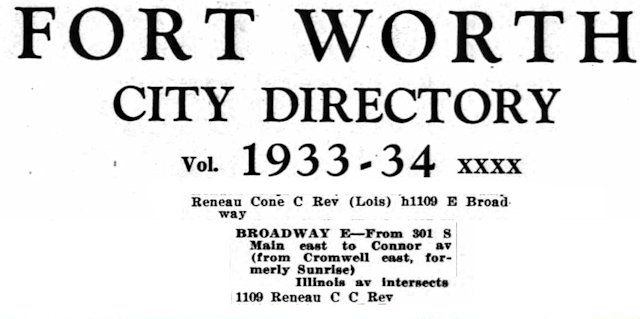

In 1917 Shaw had been an engineer for the San Antonio, Fredericksburg & Northern railroad. In 1928 he lost a leg in an accident while working as a fireman for the Trinity & Brazos Valley railroad.

In 1933 Shaw worked at the East Vickery Boulevard Mission and later for the Civil Works Administration (CWA), a short-lived jobs-creation program established by the New Deal.

Living with Shaw by October 1933 were Reverend and Mrs. C. C. Reneau. The Reneaus kept house for Shaw. Reneau had operated the East Vickery Boulevard Mission and had employed Shaw there. Reneau, like Shaw, now worked for the CWA. Shaw, forty-two, was divorced and had two children. Reverend Reneau was thirty-four. Mrs. Reneau was twenty-eight. The Reneaus had three children ages four to eight.

Living with Shaw by October 1933 were Reverend and Mrs. C. C. Reneau. The Reneaus kept house for Shaw. Reneau had operated the East Vickery Boulevard Mission and had employed Shaw there. Reneau, like Shaw, now worked for the CWA. Shaw, forty-two, was divorced and had two children. Reverend Reneau was thirty-four. Mrs. Reneau was twenty-eight. The Reneaus had three children ages four to eight.

During the two months the Reneaus had lived in Shaw’s house, Reverend Reneau had become jealous of Shaw’s attentions to his wife. Reneau often caught Shaw helping his wife cook meals and wash laundry. Sometimes Shaw and Mrs. Reneau went to the movies together. Reverend Reneau did not approve of movies.

Reneau thought Shaw showed his wife too much attention and accused his wife of accepting that attention. Shaw, for his part, thought Reneau mistreated his wife.

The two men quarreled over the accusations. Shaw threatened Reneau.

Mrs. Reneau pleaded with her husband to go stay with relatives in east Texas for his own safety. Shaw, she knew, carried a gun.

She told her husband that she and their children would join him last in east Texas.

But Reneau refused to go to east Texas.

Shaw warned Reneau not to move Mrs. Reneau out of his house. Shaw also refused to budge from his own house. The Star-Telegram later quoted a neighbor as hearing Shaw say, “I’m not going to move, and if that ——— fools with me I’ll kill him.”

On December 8 Reneau slapped his wife during a quarrel in the front yard. Neighbors were watching. In response, Shaw ordered Reneau to leave his house and warned him not to strike Mrs. Reneau again.

The next day Reneau went downtown and bought a cheap pistol at a pawn shop. He did not return to the Shaw house until about 4 a.m. December 10. He watched the house in the darkness for about thirty minutes and left. He spent some time with some “hoboes” who were camped in the nearby International & Great Northern railyard.

At dawn Reneau returned to the Shaw house. He rattled the locked front door but got no immediate response. Then he heard his wife trying to unlock the door. He also heard Shaw say, “Just let him in, I’ll kill him.”

Mrs. Reneau did not unlock the door.

Reverend Reneau went to a window of Shaw’s bedroom. In the dim light he saw Shaw sitting on the edge of his bed. Shaw was buckling on his artificial leg.

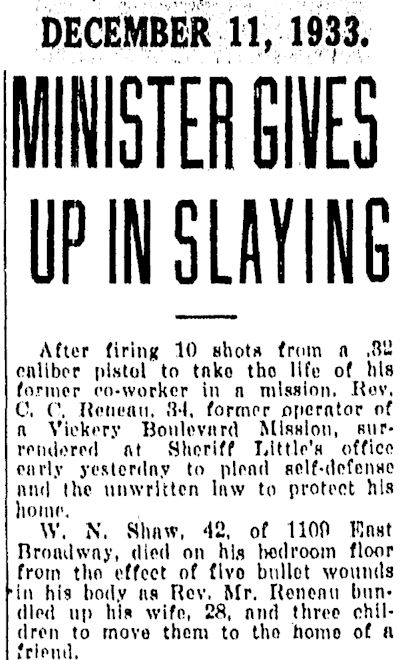

Reneau began firing through the window, emptying his pistol. He saw Shaw fall to the floor.

Reneau then ran to the front door, broke it open, went into Shaw’s bedroom. Shaw, injured, was attempting to raise himself on his elbow. Reneau stood over him and again emptied his pistol.

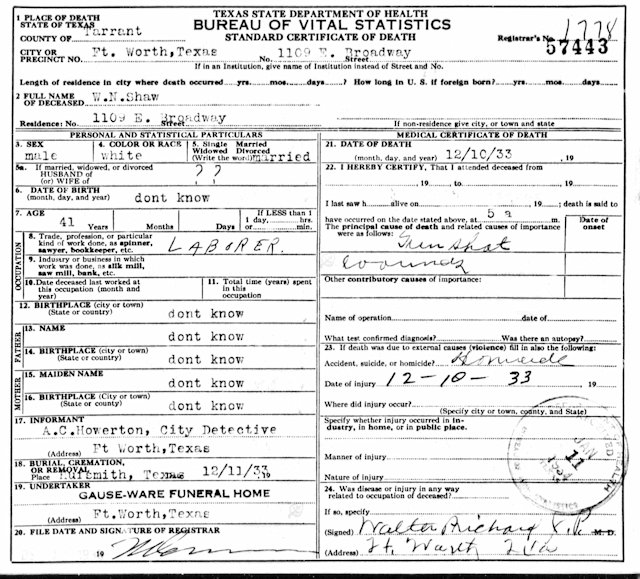

Shaw was hit five times. He died on his bedroom floor.

Shaw was hit five times. He died on his bedroom floor.

Reverend Reneau surrendered to the sheriff, was charged with murder and jailed.

Reverend Reneau surrendered to the sheriff, was charged with murder and jailed.

Reneau pleaded self-defense and the unwritten law.

The unwritten law, according to the Buffalo Law Review, was an uncodified constraint that protected “those who killed to defend the honor of women. . . . a husband, brother, or father could justifiably kill any man who had a sexual relationship outside of marriage with the killer’s wife, daughter, sister, or mother.”

The Review adds: “Criminal defendants who could convince a jury that they killed in defense of the sanctity of their home, and the virtue of their women, were almost certain to be acquitted.” (But the unwritten law was lopsided: It was not as likely to protect a wife who killed her husband’s lover.)

The unwritten law was used as a “get out of jail free” card for homicide mostly from the mid-nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth century. The unwritten law may not have been codified, but as a defense it could be as effective as any written law. For example, in addition to Reverend Reneau, these murder defendants invoked the unwritten law:

•In 1912 during the byzantine Sneed-Boyce feud John Beal Sneed shot to death A. G. Boyce Sr. and A. G. Boyce Jr. Sneed accused father and son of conspiring to take his wife from him. Sneed’s defense in court was, in part, the unwritten law. He was acquitted of both charges.

•In 1915 Fort Worth lawyer and aggrieved father Dee Estes pleaded the unwritten law after he killed a man who had been arrested for molesting Estes’s daughter. Estes shot the suspect at the jail with police as witnesses! Estes was acquitted.

•In 1917 Will Jobe shot and killed Niles City policeman Tom Finch on the sidewalk outside Monnig’s Department Store as passersby watched. Jobe’s defense team showed that his wife had been unfaithful to him with Finch. Jobe was acquitted.

The killing of Willis Napoleon Shaw by Reverend Reneau was news from the Oakland Tribune to the New York Daily News.

The killing of Willis Napoleon Shaw by Reverend Reneau was news from the Oakland Tribune to the New York Daily News.

At his examining trial Reneau acted as his own counsel.

When Reneau tried to call his daughter May, age eight, to the witness stand, she shook her head.

“No, Daddy.”

Mrs. Reneau spoke up: “No, the child doesn’t want to go on.”

Mrs. Reneau agreed to take the stand for the defense.

“Did Shaw threaten to kill me if I moved you away?” Reneau asked his wife.

“Shaw did not threaten to kill you if you moved us away,” said his wife, “unless you beat me like you did in the street before all the neighbors.”

Reneau admitted that he had slapped his wife during a quarrel in front of the house. “I hate to tell about it, but I gave her a pretty good spanking.”

Mrs. Reneau admitted that Shaw had threatened to turn her husband over to the Ku Klux Klan, first to have him tarred and feathered and thrown out on Main Street in Dallas, and second to “stake you out and burn you alive.”

Mrs. Reneau said she believed in the Ku Klux Klan “with all my heart.”

Questioned about events on the morning of the killing, Mrs. Reneau said she had slept in her “big bed with my three babies.” She said she was troubled and slept very little. Shortly before her husband shot Shaw, she testified, Shaw called and she went into his room. She said she was fully dressed.

“Tell the truth,” Reneau warned.

“I am telling the truth,” she said.

City police detective A. C. Howerton testified that the bed in which Mrs. Reneau said she had slept was undisturbed but that Shaw’s bed bore the imprint of two bodies.

“I didn’t want trouble,” Reneau told the court. “I fasted and prayed for a peaceful way out.”

Reverend Reneau was released on his own recognizance after an assistant district attorney said he did not think the accused would be indicted by the grand jury.

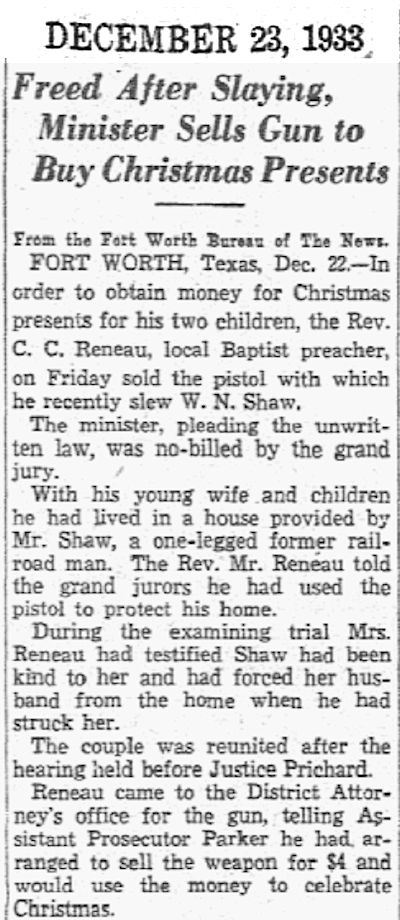

And the assistant DA was right. Reverend Reneau was no-billed by the grand jury.

And the assistant DA was right. Reverend Reneau was no-billed by the grand jury.

On December 22 Reverend Reneau got his pistol back from the district attorney, went to a pawn shop, got $4 ($80 today) for the gun, and used the money to buy presents for his children.