The year was 1878, and Fort Worth civic leaders were facing a fact as cold and hard as a steel rail: The end was nigh.

Or, more literally, the end of the end was nigh.

See, in 1873 the Texas & Pacific railroad had laid track westward from Longview, headed for Fort Worth, bringing Cowtown its first railroad.

See, in 1873 the Texas & Pacific railroad had laid track westward from Longview, headed for Fort Worth, bringing Cowtown its first railroad.

Yippie, right?

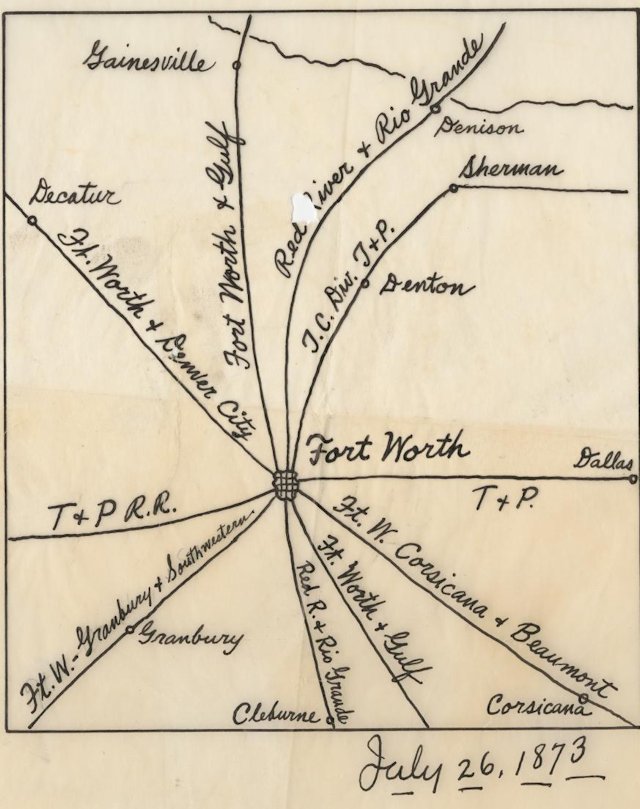

In fact, Fort Worth civic leader and Fort Worth Democrat publisher B. B. Paddock was so certain in 1873 that the T&P soon would be the first of several railroads to serve Fort Worth that he drew his “tarantula map” envisioning Fort Worth as a future railroad hub with railroad lines radiating like legs of a spider. (Some of the railroads anticipated by his map never materialized.) (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

Well, the T&P had reached Dallas—a scant thirty miles from Fort Worth—when the financial panic of 1873 knee-capped the national economy in September. The T&P stopped laying track westward and walked away, leaving Fort Worth to sing the “So Near, Yet So Far” blues.

The next year the T&P laid six more miles of track, reaching Eagle Ford west of Dallas. Then the T&P walked away again, leaving Fort Worth just twenty-four miles from its future. Another chorus of “So Near, Yet So Far.”

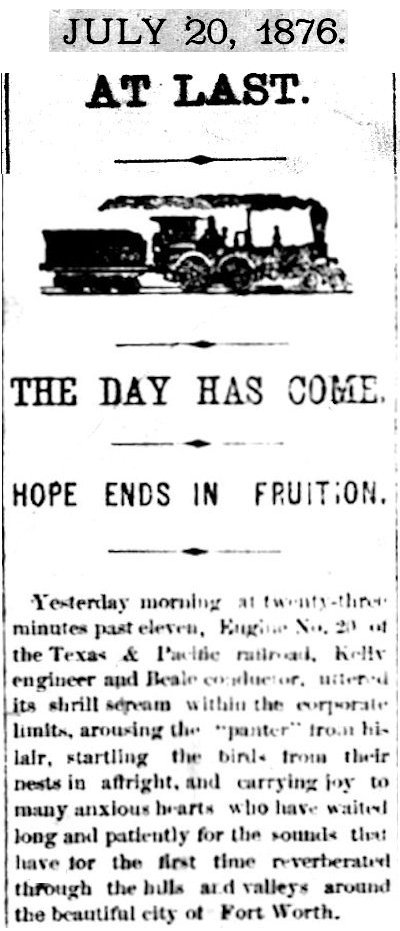

Fast-forward two years. “At Last. The Day Has Come. Hope Ends in Fruition.” The T&P, with some help from Fort Worth residents, finally laid those twenty-four miles of track from Eagle Ford to Fort Worth, and on July 19, 1876 the first train rolled into town.

Fast-forward two years. “At Last. The Day Has Come. Hope Ends in Fruition.” The T&P, with some help from Fort Worth residents, finally laid those twenty-four miles of track from Eagle Ford to Fort Worth, and on July 19, 1876 the first train rolled into town.

Then the T&P construction crew walked away again. Did not lay another foot of track westward.

But Fort Worth didn’t complain this time. Because not only did Fort Worth finally have the railroad, but also Fort Worth was the terminus town: the end of the line, the westernmost town on the T&P line from Marshall. And there were economic advantages to that status.

The vastness of west Texas was being settled at a rapid rate. The government was pushing settlement. So were the railroads, which published for immigrants brochures promoting the many advantages of Texas. Many of the immigrants looking for cheap land and wide open spaces or a new start in a new town traveled by train. They had to get off at Fort Worth: the end of the line. Some of them settled in Fort Worth. Others continued on westward. After they got settled, the nearest town of any size where they could spend their money (groceries, supplies, entertainment) was Fort Worth.

Too, farmers and ranchers wanting to ship everything from cotton to cattle by rail came to Fort Worth as the terminus town.

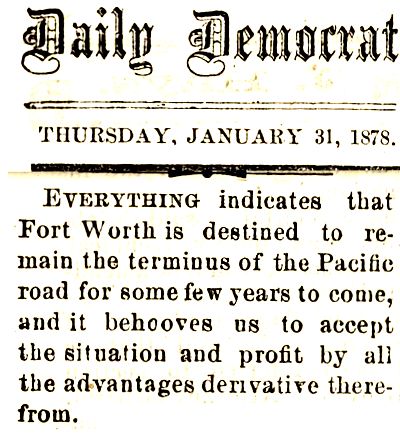

Fast-forward to 1878. Terminus town Fort Worth was booming. And the Democrat assured readers that Fort Worth would remain the terminus town for “some few years to come.” The Democrat urged Fort Worth to profit from the “advantages derivative therefrom.”

Fast-forward to 1878. Terminus town Fort Worth was booming. And the Democrat assured readers that Fort Worth would remain the terminus town for “some few years to come.” The Democrat urged Fort Worth to profit from the “advantages derivative therefrom.”

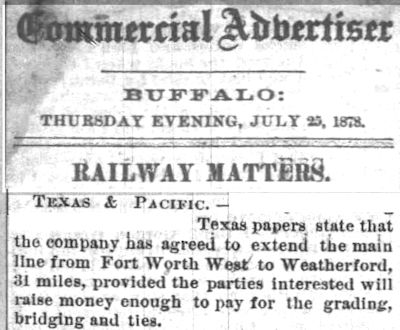

Then came bad news: The Texas & Pacific railroad had agreed to extend its track westward from Fort Worth to Weatherford if the “parties interested” paid for the preparatory work.

Then came bad news: The Texas & Pacific railroad had agreed to extend its track westward from Fort Worth to Weatherford if the “parties interested” paid for the preparatory work.

Weatherford—a party very interested—had been waiting two years for that go-ahead. In 1876 Weatherford, like Fort Worth, had organized a construction company to finance the preparatory work for the T&P track from Dallas. But the T&P had stopped laying track at Fort Worth—thirty miles from Weatherford.

Now that the T&P was ready to lay track again, the Parker County Construction Company raised $100,000 ($2.6 million today) to finance preparation of the right-of-way from Fort Worth to Weatherford. And a lot of preparation was necessary: surveying, clearing, and grading the right-of-way, excavating cuts in hills, installing culverts, building trestles, erecting water tanks and digging wells to fill them.

In late 1878 that work began.

Doomsayers were quick to predict the demise of Fort Worth after it lost its terminus town status.

Doomsayers were quick to predict the demise of Fort Worth after it lost its terminus town status.

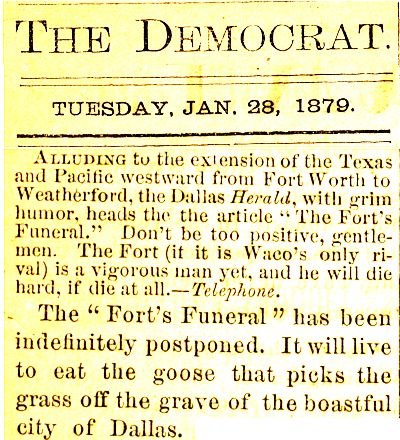

“Nonsense!” insisted the Democrat. In January 1879 the Democrat responded to an article in the Dallas Herald entitled “The Fort’s Funeral” that suggested that the Weatherford extension would be the death of Fort Worth. The Democrat predicted that Fort Worth would “live to eat the goose that picks the grass off the grave of the boastful city of Dallas.”

By February 1879 six miles of right-of-way had been graded between Fort Worth and Weatherford.

By February 1879 six miles of right-of-way had been graded between Fort Worth and Weatherford.

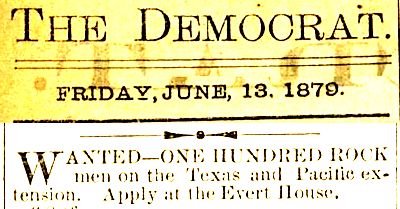

In June 1879 one of the roadbed contractors was hiring one hundred “rock men.”

(The Evert House was a hotel on Throckmorton Street.)

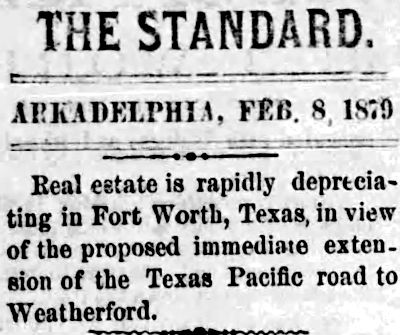

Fort Worth’s leaders, via the Democrat, continued to project confidence as the dire predictions spread. An Arkadelphia newspaper reported that real estate values in Fort Worth had dropped because Weatherford was going to be the new terminus town.

Fort Worth’s leaders, via the Democrat, continued to project confidence as the dire predictions spread. An Arkadelphia newspaper reported that real estate values in Fort Worth had dropped because Weatherford was going to be the new terminus town.

Ever since 1876 the extension of the T&P track west from Fort Worth had been a juicy bone of contention between Fort Worth and Dallas.

Ever since 1876 the extension of the T&P track west from Fort Worth had been a juicy bone of contention between Fort Worth and Dallas.

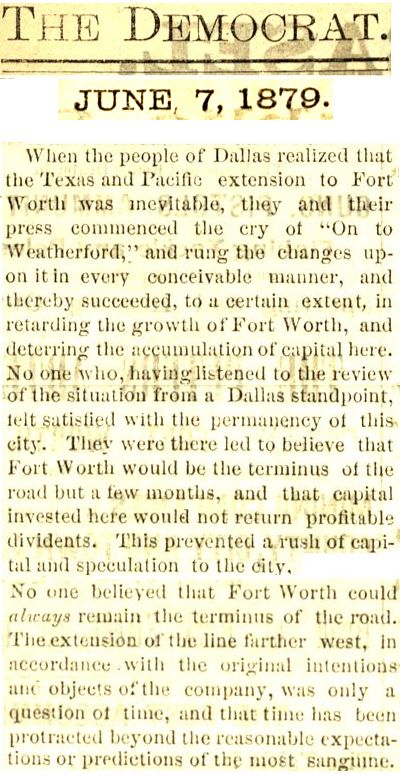

Fort Worth, via the Democrat, complained that in 1876, when track-laying from Dallas had resumed, the people and press of Dallas had hoped that Weatherford, not Fort Worth, would be the new terminus town.

The Democrat also accused Dallas of “retarding” the growth of Fort Worth by predicting that Fort Worth would be the terminus town only briefly and thus would not repay any investment by capitalists.

Dallas newspapers accused Paddock and his Democrat of opposing the extension to Weatherford. Paddock cried foul, insisting that the Democrat’s stance all along had been that the extension to Weatherford was inevitable but should be built only when circumstances dictated. It should not be rushed.

(Which some folks in Weatherford interpreted to mean “Fort Worth had to wait; let Weatherford wait, too.”)

Paddock also groused that Dallasites helped to fund the Parker County Construction Company just to spite Fort Worth.

Meow!

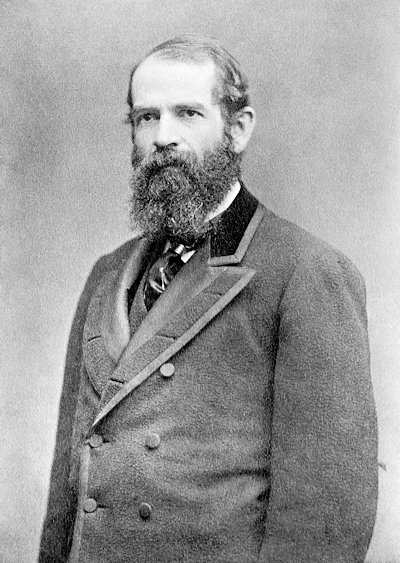

Then came another blow to Fort Worth. In 1879 financier Jay Gould, who controlled more railroads than Lionel (Union Pacific, Kansas Pacific, Denver Pacific, Central Pacific, Missouri Pacific) gained control of one more Pacific: the Texas & Pacific. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

Then came another blow to Fort Worth. In 1879 financier Jay Gould, who controlled more railroads than Lionel (Union Pacific, Kansas Pacific, Denver Pacific, Central Pacific, Missouri Pacific) gained control of one more Pacific: the Texas & Pacific. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

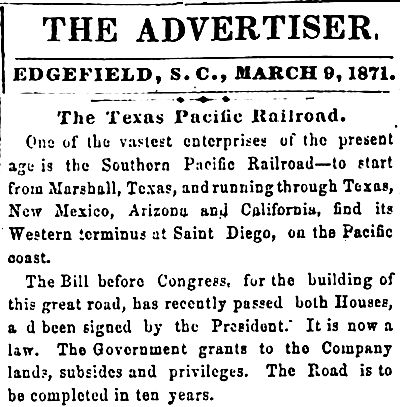

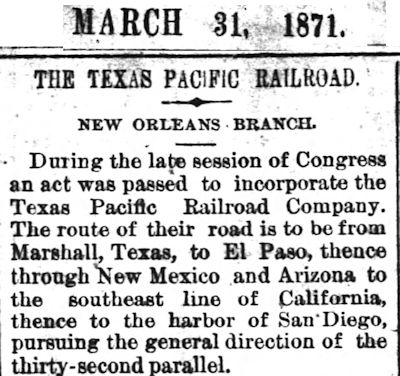

Jay Gould was not a man to dilly or dally. He organized a syndicate to provide funding to complete the task that was implied in the very name of the Texas & Pacific railroad when it had been chartered by Congress in 1871: build a transcontinental railroad line from Texas to the Pacific, not just from Longview to Fort Worth.

Jay Gould was not a man to dilly or dally. He organized a syndicate to provide funding to complete the task that was implied in the very name of the Texas & Pacific railroad when it had been chartered by Congress in 1871: build a transcontinental railroad line from Texas to the Pacific, not just from Longview to Fort Worth.

Gould’s syndicate agreed to provide $25,000 for labor and material for every mile of track laid west of Fort Worth. T&P’s chief civil engineer estimated that track could be laid for half that amount.

And Gould would have more help: Collis Huntington’s Southern Pacific railroad would lay track east from California to Texas. Gould’s T&P would lay track west from Texas toward California. The train twain would meet in the middle: the western edge of Texas.

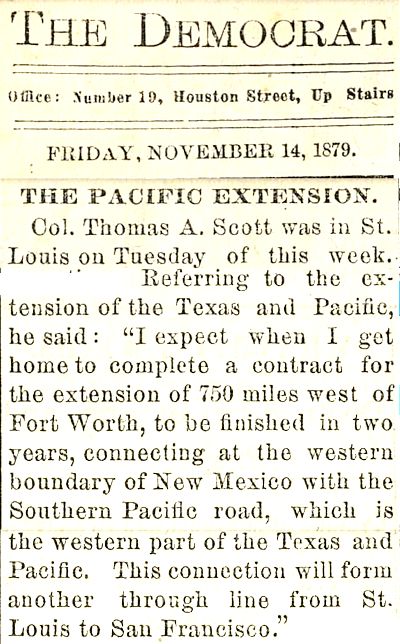

T&P’s work would begin where it had ended in 1876: in Fort Worth. T&P honcho Colonel Tom Scott said track would be laid from Fort Worth west 750 miles to connect with the Southern Pacific track.

T&P’s work would begin where it had ended in 1876: in Fort Worth. T&P honcho Colonel Tom Scott said track would be laid from Fort Worth west 750 miles to connect with the Southern Pacific track.

Yes, soon hammers would ring again, wheels would roll again.

And that meant that soon Weatherford, not Fort Worth, would be the terminus town—if only temporarily—and profit from the “advantages derivative therefrom.”

Paddock and Fort Worth’s other civic leaders were forced to look for the silver lining in the cloud over Fort Worth. Paddock’s own tarantula map envisioned Fort Worth as a railroad hub, not Fort Worth as a terminus down with a single railroad. Fort Worth could not have it both ways—remain a terminus town and become a railroad hub. Fort Worth had to give up its terminus status to attain tarantula status. As of 1878 Paddock’s tarantula had only one leg—the T&P line from the east. With the Weatherford extension to the west, Fort Worth would grow a second leg.

And economically speaking, Paddock et al. reassured themselves, a tarantula with two legs gets asked to dance more often than does a tarantula with one leg.

Fort Worth’s economy would suffer at first, but, Paddock and others were convinced, Fort Worth eventually would rebound.

The immediate silver lining was this: Fort Worth’s status as the terminus town made it the obvious choice to be the initial construction headquarters for the T&P’s big push westward.

Thus, Fort Worth enjoyed an immediate boom as headquarters buildings, including offices and a supply depot, were built. All men and material bound for the ever-advancing western terminus of the track would pass through Fort Worth.

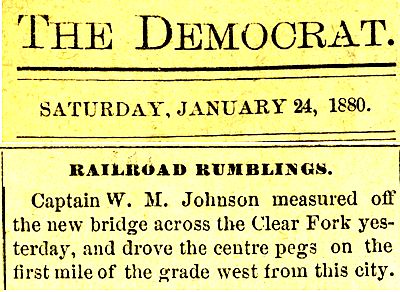

In January 1880 the Democrat began its “Railroad Rumblings” column to report on the track-laying. Construction workers would build about three hundred bridges between Fort Worth and El Paso. The first was over the Clear Fork of the Trinity River, only two miles from the Fort Worth depot but well outside the city limits.

In January 1880 the Democrat began its “Railroad Rumblings” column to report on the track-laying. Construction workers would build about three hundred bridges between Fort Worth and El Paso. The first was over the Clear Fork of the Trinity River, only two miles from the Fort Worth depot but well outside the city limits.

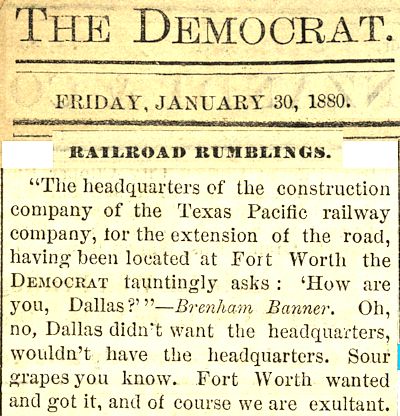

Paddock also used the “Railroad Rumblings” column to tweak the nose of Dallas. In January 1880 he crowed that Dallas had wanted to be the location of the T&P’s construction headquarters until Fort Worth was selected. Then Dallas, according to Paddock, pretended it had not wanted the economic plum in the first place. Sour grapes!

Paddock also used the “Railroad Rumblings” column to tweak the nose of Dallas. In January 1880 he crowed that Dallas had wanted to be the location of the T&P’s construction headquarters until Fort Worth was selected. Then Dallas, according to Paddock, pretended it had not wanted the economic plum in the first place. Sour grapes!

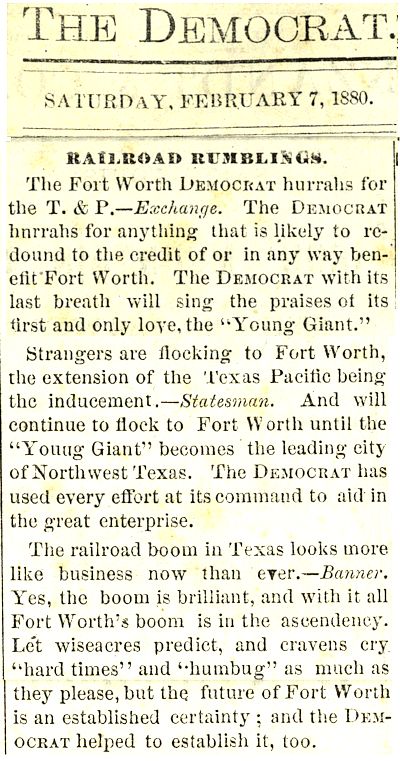

Paddock and the Democrat whistled in the graveyard and scoffed at the “wiseacres” who predicted that Fort Worth—the “Young Giant”—would fall upon “hard times” after it lost its status as the terminus town. (Soon after the T&P had reached Fort Worth in 1876, the Democrat had begun to refer to Fort Worth rather grandiosely as “the young giant of the west.”)

Paddock and the Democrat whistled in the graveyard and scoffed at the “wiseacres” who predicted that Fort Worth—the “Young Giant”—would fall upon “hard times” after it lost its status as the terminus town. (Soon after the T&P had reached Fort Worth in 1876, the Democrat had begun to refer to Fort Worth rather grandiosely as “the young giant of the west.”)

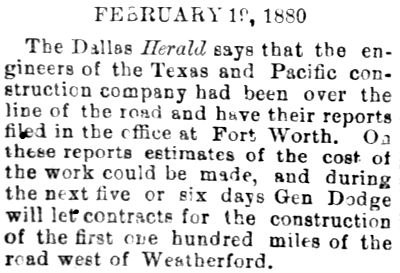

In mid-February the Dallas Herald reported that General Dodge would soon let contracts for construction of the first hundred miles of track west of Weatherford.

The work laying track to El Paso would be hard, the pay would be low. Summers would be hot, winters cold. And as work began, General Dodge warned his civil engineers of one more occupational hazard: “I lay down the following general rules to be observed . . . The party taking the field must be armed, and the chief must be a man of energy and one who will not run at the sight of an Indian.”

Grenville Mellen Dodge (1831-1916) was one of the master railroad builders of the nineteenth century. He had been the Union Pacific railroad’s chief engineer as the first transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869. General Dodge also had become Fort Worth’s iron angel. He had been the ramrod pushing the Texas & Pacific from Longview west to Dallas in 1873 (and ultimately to Fort Worth in 1876). Now, in 1880, he was the ramrod pushing the T&P west from Fort Worth toward El Paso and a connection to California. And in 1888 he would ramrod construction of the Fort Worth & Denver City railroad between those namesake cities. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

Grenville Mellen Dodge (1831-1916) was one of the master railroad builders of the nineteenth century. He had been the Union Pacific railroad’s chief engineer as the first transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869. General Dodge also had become Fort Worth’s iron angel. He had been the ramrod pushing the Texas & Pacific from Longview west to Dallas in 1873 (and ultimately to Fort Worth in 1876). Now, in 1880, he was the ramrod pushing the T&P west from Fort Worth toward El Paso and a connection to California. And in 1888 he would ramrod construction of the Fort Worth & Denver City railroad between those namesake cities. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

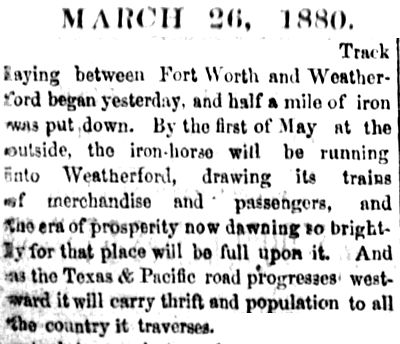

Work on the right-of-way between Fort Worth and Weatherford had been slow during 1879 because of funding shortages and resultant worker strikes. But by March 1880 the right-of-way between Fort Worth and Weatherford was prepared. The first rails were laid on March 25.

Work on the right-of-way between Fort Worth and Weatherford had been slow during 1879 because of funding shortages and resultant worker strikes. But by March 1880 the right-of-way between Fort Worth and Weatherford was prepared. The first rails were laid on March 25.

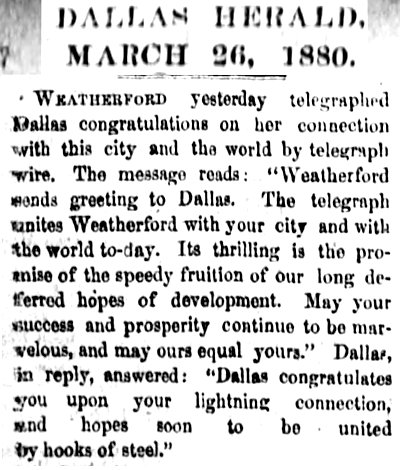

The extension of the railroad from Fort Worth was actually a twofer for people living to the west. The extension brought not only railroad service but also telegraph service! As workers cleared and graded right-of-way, telegraph poles were set and wire strung. State-of-the art communication and transportation advanced in lock step toward El Paso.

The extension of the railroad from Fort Worth was actually a twofer for people living to the west. The extension brought not only railroad service but also telegraph service! As workers cleared and graded right-of-way, telegraph poles were set and wire strung. State-of-the art communication and transportation advanced in lock step toward El Paso.

Thus, March 25, 1880 was a day of double delight for Weatherford: Not only were rails finally being laid, but also Weatherford was connected to the world by telegraph.

Note that Weatherford sent its first telegraph to Dallas, not to Fort Worth.

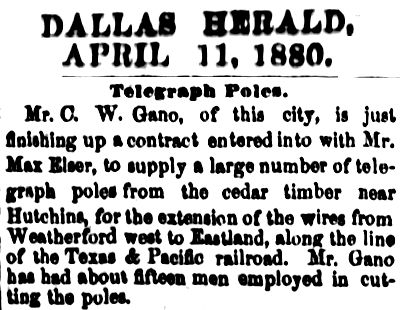

And who installed the telegraph line along the T&P right-of-way as it progressed westward?

And who installed the telegraph line along the T&P right-of-way as it progressed westward?

Fort Worth’s Max Elser, who in 1874 had also connected Fort Worth to Dallas via telegraph.

Three types of towns could be found along the new railroad line to the west:

Three types of towns could be found along the new railroad line to the west:

- existing towns, such as Benbrook (originally “Miranda”), Weatherford, and Eastland

- new towns, such as Abilene, Midland, and Odessa

- towns that, rather than be bypassed by the railroad track, packed up and moved—kit and caboodle and cuspidor—to the new track, such as Annetta, Ranger, and Cisco

In all three types town lots were sold. Often the lots were owned and sold by the Texas & Pacific railroad itself. The state of Texas had granted land to the railroad for each mile of track laid.

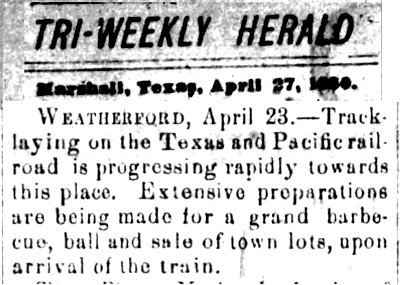

As the news clipping shows, in April 1880 town lots were sold in Weatherford.

Some of those town lots in cities would be bought by immigrants moving to Texas.

Some of those town lots in cities would be bought by immigrants moving to Texas.

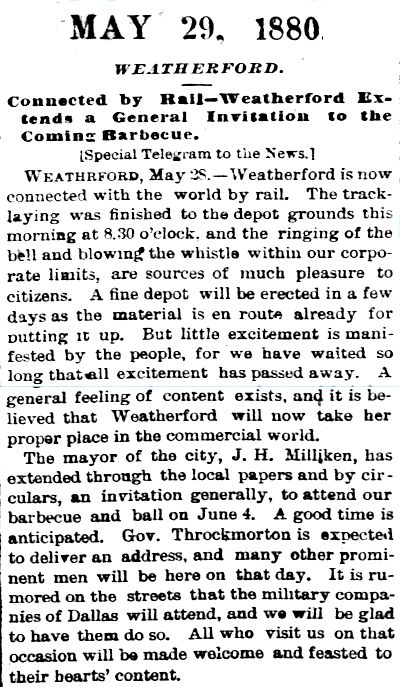

And then, on May 28, there it was in cold, hard steel: The railroad had reached Weatherford. Twenty-eight months after the Democrat had predicted that Fort Worth would remain the terminus for “some few years to come,” Weatherford was the new terminus.

And then, on May 28, there it was in cold, hard steel: The railroad had reached Weatherford. Twenty-eight months after the Democrat had predicted that Fort Worth would remain the terminus for “some few years to come,” Weatherford was the new terminus.

Ah, but at least now Fort Worth’s tarantula had its second leg: a second leg to dance on. Granted, it was a short leg, but it would grow: all the way to the Pacific Ocean.

Ah, but at least now Fort Worth’s tarantula had its second leg: a second leg to dance on. Granted, it was a short leg, but it would grow: all the way to the Pacific Ocean.

As Fort Worth and Weatherford knew all too well, in the 1870s building a railroad had been a hurry-up-and-wait process. For example, in mid-1878 the Texas & Pacific had announced its willingness to extend the track thirty miles from Fort Worth to Weatherford. That track was not completed until May 1880.

Conversely, in the 1880s building a railroad, behind men such as Gould and Huntington, would be a get-up-and-go process. In the twenty-two months between mid-1878 and May 28, 1880 the T&P had laid thirty miles of track. In the next twenty months the T&P would lay five hundred miles of track.

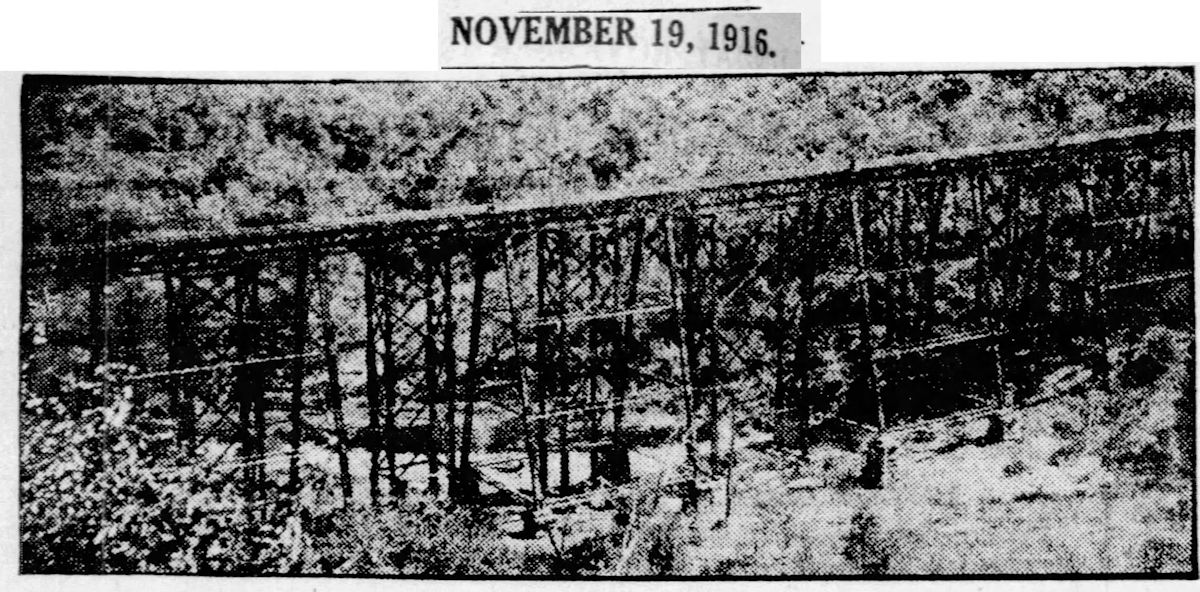

One of the T&P’s first challenges as it laid track west of Weatherford was crossing the Brazos River in Palo Pinto County. The railroad bridge over the Brazos had three spans of 230 feet and an eastern approach of 900 feet of trestling. The bridge was eighty feet high, built with 2,000 cubic yards of masonry and 400,000 feet of lumber.

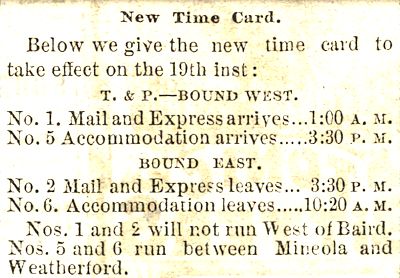

By September 16, 1880 the track had reached the new town of Gordon forty-two miles west of Weatherford. The town was named for H. L. Gordon, a T&P civil engineer. Now the town of Gordon, not Weatherford, was the terminus town.

But only briefly.

The next engineering challenge for the T&P was crossing the canyons of Palo Pinto Creek ten miles west of Strawn. Trestles of 600, 800, 750, and 1,300 feet were built using two million feet of lumber. This photo from 1916 shows one of the trestles over the creek.

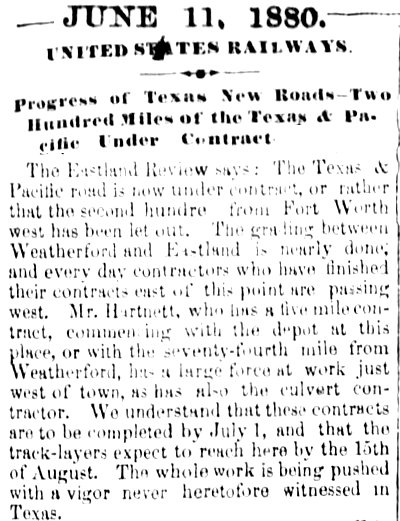

The town of Eastland already existed in 1880. On June 11 the Eastland Review reported that the right-of-way had been graded almost to that town and that “the track-layers expect to reach here by the 15th of August.”

The town of Eastland already existed in 1880. On June 11 the Eastland Review reported that the right-of-way had been graded almost to that town and that “the track-layers expect to reach here by the 15th of August.”

The people of Eastland had made a deal with the T&P: We’ll give you some town lots to sell if you will include our town on your line.

The people of Eastland had made a deal with the T&P: We’ll give you some town lots to sell if you will include our town on your line.

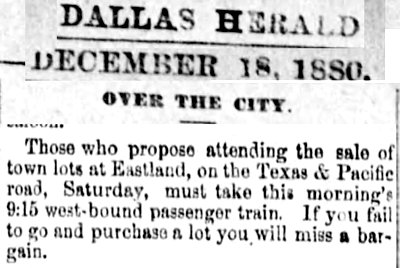

In December 1880 those town lots went on sale.

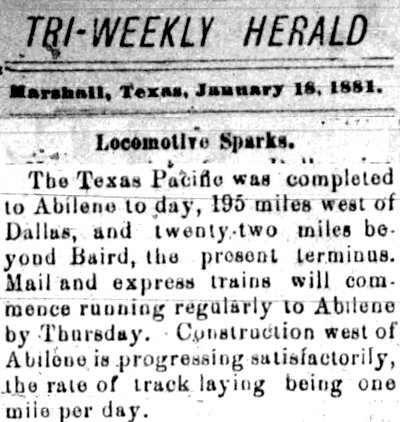

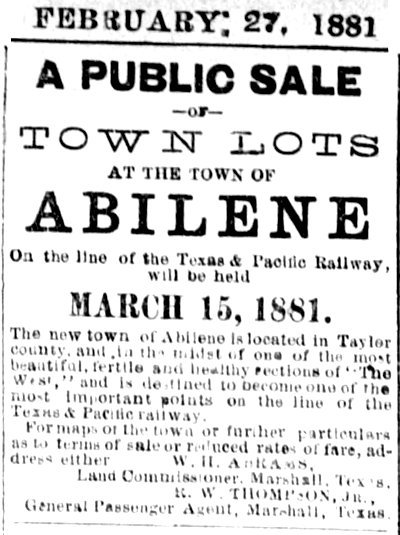

By early 1881 the track had reached Abilene, a new town.

By early 1881 the track had reached Abilene, a new town.

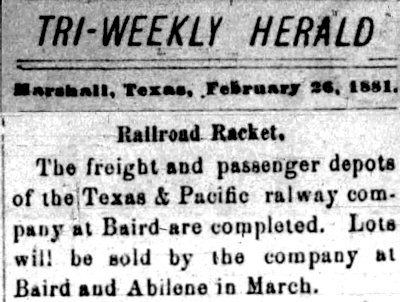

By February the depots were completed in Baird, another new town on the line, named after Matthew Baird, a director of the Texas & Pacific railroad. He also owned the Baldwin Locomotive Works, the largest locomotive manufacturer in the United States.

By February the depots were completed in Baird, another new town on the line, named after Matthew Baird, a director of the Texas & Pacific railroad. He also owned the Baldwin Locomotive Works, the largest locomotive manufacturer in the United States.

In March town lots would be sold in “the new town of Abilene,” “destined to become one of the most important points on the line of the Texas & Pacific railway.”

In March town lots would be sold in “the new town of Abilene,” “destined to become one of the most important points on the line of the Texas & Pacific railway.”

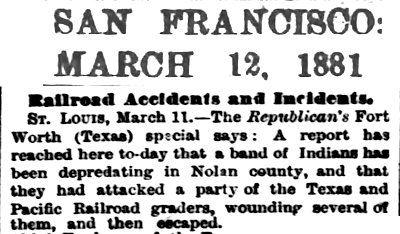

Meanwhile graders in Nolan County (Sweetwater) encountered road hazards.

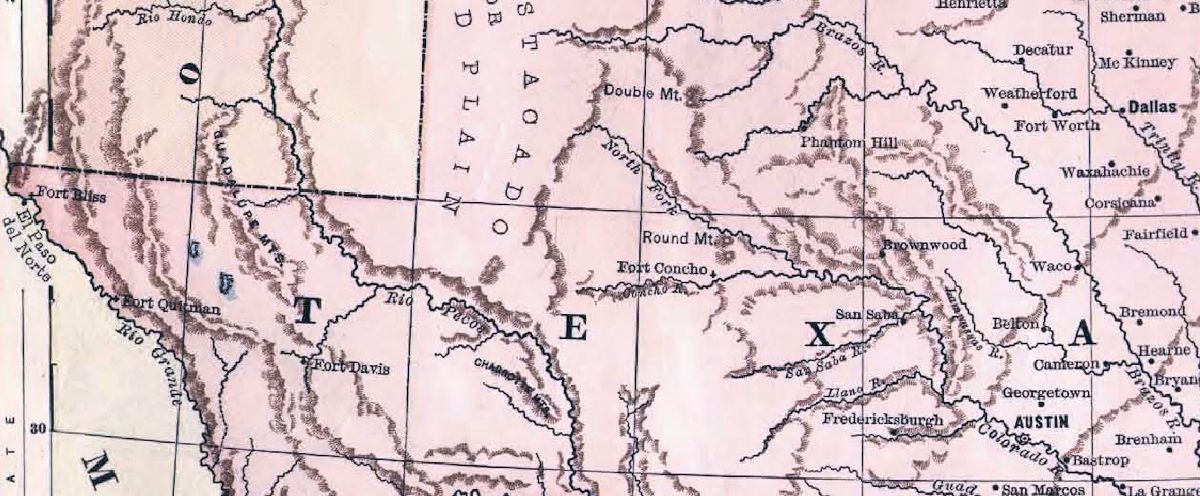

This 1879 map shows how few towns existed between Fort Worth and El Paso. West of Abilene, born of steam and steel in 1881 would be Colorado City . . . Big Spring . . . Midland (originally named “Midway Station” because it is midway on the T&P line between Fort Worth and El Paso) . . . Odessa . . . Monahans . . . Pecos.

This 1879 map shows how few towns existed between Fort Worth and El Paso. West of Abilene, born of steam and steel in 1881 would be Colorado City . . . Big Spring . . . Midland (originally named “Midway Station” because it is midway on the T&P line between Fort Worth and El Paso) . . . Odessa . . . Monahans . . . Pecos.

As each town was born, everything had to be hauled in. There was no Home Depot. Towns may have been platted and lots sold, but in the beginning residents lived in tents until lumber and nails could be hauled in for permanent housing. Most structures, from homes to saloons, were made of sheet metal or canvas. Wells had to be dug or water hauled in from a spring. Schools, churches, law enforcement were niceties of the future.

After the track was laid, section houses for permanent workers and depots were built, wells were dug and water tanks were erected every twenty miles. In each of the T&P’s three division towns (Baird, Big Spring, Toyah) between Fort Worth and El Paso, a roundhouse, turntable, and repair shops were built.

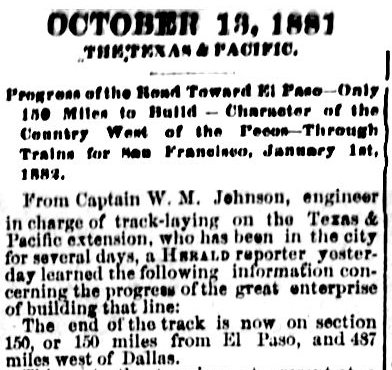

By October 1881 the track was only 150 miles from El Paso.

By October 1881 the track was only 150 miles from El Paso.

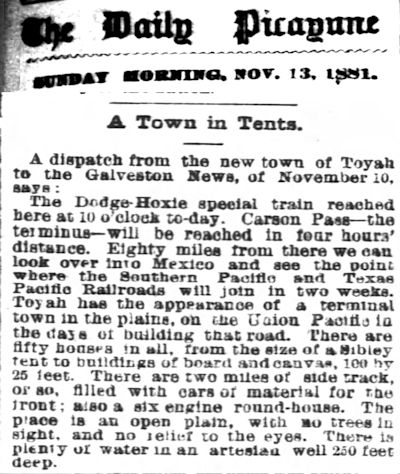

By November the T&P construction headquarters had been moved west to Toyah, “a town in tents.” The news article calls Toyah a “new town,” but it already existed. Toyah was a Native American word meaning “flowing water.”

By November the T&P construction headquarters had been moved west to Toyah, “a town in tents.” The news article calls Toyah a “new town,” but it already existed. Toyah was a Native American word meaning “flowing water.”

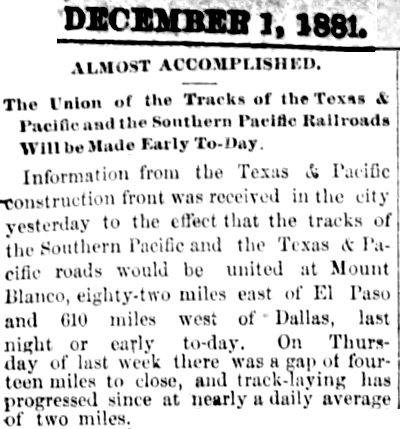

At last, on December 1, 1881 newspapers reported that the meeting of the Texas & Pacific track and the Southern Pacific track was imminent at Sierra Blanca, Texas, eighty miles southeast of El Paso.

At last, on December 1, 1881 newspapers reported that the meeting of the Texas & Pacific track and the Southern Pacific track was imminent at Sierra Blanca, Texas, eighty miles southeast of El Paso.

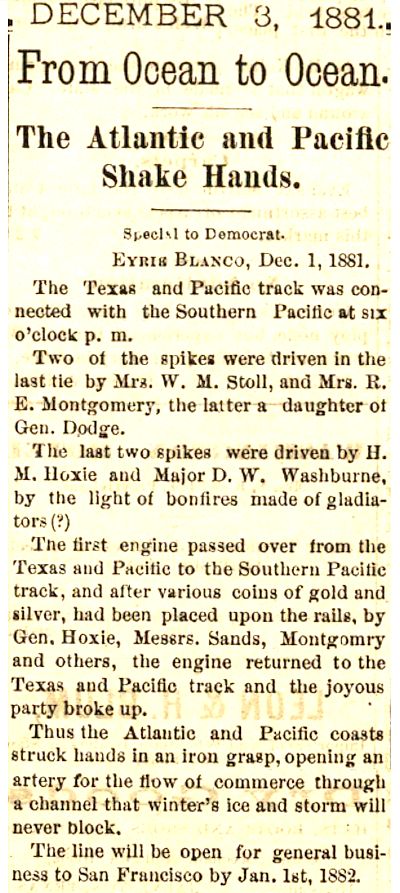

“The Atlantic and Pacific Shake Hands” read the headline in B. B. Paddock’s Democrat on December 3. “Thus the Atlantic and Pacific coasts struck hands in an iron grasp, opening an artery for the flow of commerce through a channel that winter’s ice and storm will never block.”

“The Atlantic and Pacific Shake Hands” read the headline in B. B. Paddock’s Democrat on December 3. “Thus the Atlantic and Pacific coasts struck hands in an iron grasp, opening an artery for the flow of commerce through a channel that winter’s ice and storm will never block.”

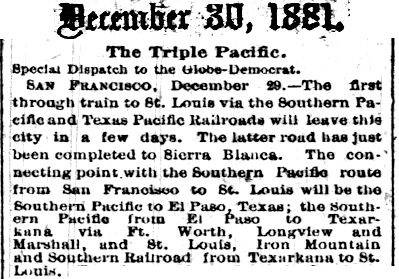

Fort Worth and San Francisco were now neighbors connected by bands of steel.

Fort Worth and San Francisco were now neighbors connected by bands of steel.

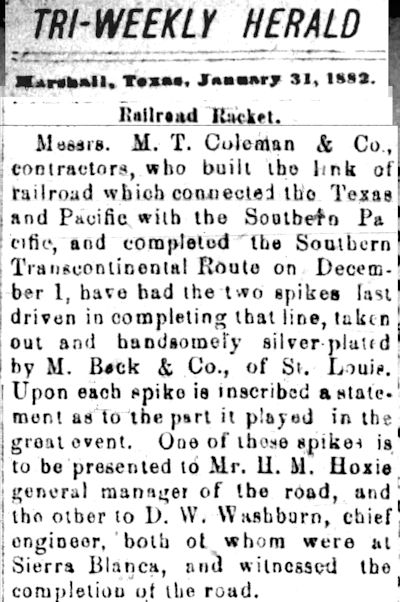

In January 1882 the final two spikes driven at the union of the two railroads were pulled, silver-plated, engraved, and presented to T&P general manager H. M. Hoxie and T&P civil engineer D. W. Washburn.

In January 1882 the final two spikes driven at the union of the two railroads were pulled, silver-plated, engraved, and presented to T&P general manager H. M. Hoxie and T&P civil engineer D. W. Washburn.

Connecting Fort Worth to Sierra Blanca had been a monumental feat of engineering and labor. Hundreds of men had laid an average of a mile and a half of rail a day for twenty months. Those 521 miles of track consumed 50,000 tons of rails, 2,000 tons of spikes, 4,000 tons of angle plates, and 1,500,000 crossties: 20,000 carloads of material.

Twenty-two depots, fifty section houses, and three hundred bridges had been built, fifteen thousand telegraph poles sunk.

Those 521 miles of track had ramifications far beyond merely connecting Fort Worth to Sierra Blanca. Now the nation had two transcontinental railroad routes. In the future lateral lines would connect the two transcontinental routes. Railroad lines would multiply exponentially. From coast to coast dozens of towns would be connected to dozens of other towns via rail and telegraph wire: a primitive internet.

The world would shrink.

Newly connected existing towns such as Benbrook, Weatherford, and Eastland would grow because of the railroad; new railroad towns such as Abilene, Midland, and Odessa would thrive.

The vastness of west Texas would be opened up to farming and ranching. Some railroad towns would become shipping points for cattle as the railroad replaced cattle drives.

Now Texas was connected to California on the Pacific coast. A person in Fort Worth could ride a train to San Francisco and sail on a steamship to Hong Kong or Tokyo. Oranges from California, silk from China, pineapples from Hawaii could be shipped by rail to Fort Worth.

I like to picture B. B. Paddock on December 1, 1881 as those final two spikes were being driven 521 miles to the west: He puts his ear to a rail of the Texas & Pacific track at the Fort Worth depot, listens, and announces, with a smile, “I can hear the ocean!”

So. What came next for Fort Worth after it lost its terminus status and became just another stop along the transcontinental railroad?

Fort Worth’s population in 1880, when it lost its terminus town status, was 6,600. By 1890 its population had tripled to 23,000.

Why?

Because during the twenty months those 521 miles of track were being laid westward, Paddock and other civic leaders had been working to transform Fort Worth from a terminus town to a railroad hub.

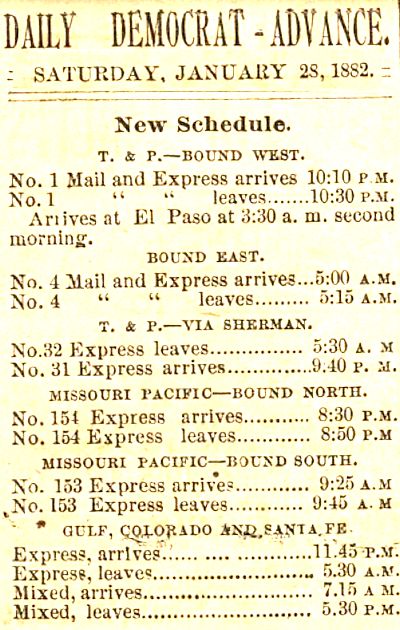

By the time the final two spikes at Sierra Blanca were silver-plated and engraved, Fort Worth’s tarantula had grown not only its second leg with the new T&P western line but also a T&P line north to Sherman, Missouri Pacific lines north and south, and a Santa Fe line south.

By the time the final two spikes at Sierra Blanca were silver-plated and engraved, Fort Worth’s tarantula had grown not only its second leg with the new T&P western line but also a T&P line north to Sherman, Missouri Pacific lines north and south, and a Santa Fe line south.

The tarantula was ready to rumba.

Also from the 1884 T&P Rwy annual report:

“Very substantial progress has been made during the year in the number of newer towns along the line…west of Ft. Worth. The stations of Putnam, Merkel, Marienfeld, Midland, and Pecos are those in which the growth has been most noticeable.”

Thanks, Dennis. It’s just an epic accomplishment, a story out of Hollywood. (“Jimmy Stewart, stand defiantly on that cowcatcher!” “Duke Wayne, your line is ‘Damn the Injuns! I got a date with El Paso!'”)

Annual report of the T&P for 1884 stated:

“The estimated expenditure required to be made during the years 1884-1887…[projects]filling in and replacing three high trestles on the Rio Grande Division, and…”

And all done without power tools, laser levels, cranes, hydraulics, etc. I swung a pick about ten minutes today and had to come inside and rest. If all those rail layers had been as fit as me, that track would still not be to the Brazos River.

Lots of wood trestles were required west of Strawn. Some were replaced with steel bridges and others just filled in years later.

The construction of the T&P west of Ft. Worth is an unheralded feat. (Hopefully Gerald Hook and I will tell that story someday soon with our research.)

It is truly a great story of Texas.