At a mere ninety-one years of age, Rose Hill is one of the newest of our public cemeteries.

Rose Hill was developed in 1929 by John James Harden, who built the Fort Worth Public Market Building. Harden also built public market buildings in Tulsa and Oklahoma City and Rose Hill cemeteries in Tulsa and Oklahoma City.

Rose Hill was developed in 1929 by John James Harden, who built the Fort Worth Public Market Building. Harden also built public market buildings in Tulsa and Oklahoma City and Rose Hill cemeteries in Tulsa and Oklahoma City.

Harden developed Rose Hill as he was developing the Bluebonnet Hills addition south of TCU.

The Rose Hill property once had been part of a land grant awarded to the heirs of R. R. Ramey for his service in the Texas Revolution. The land later was owned by Major James Handley (see below), for whom the town was named. Still later the land was owned by Paul Waples, who leased part of it to the Swift packing company.

The Rose Hill property once had been part of a land grant awarded to the heirs of R. R. Ramey for his service in the Texas Revolution. The land later was owned by Major James Handley (see below), for whom the town was named. Still later the land was owned by Paul Waples, who leased part of it to the Swift packing company.

Rose Hill is indeed on a hill. The sandstone chapel at the top of the hill is ninety feet higher than the entrance gate at Sandy Lane and Lancaster Avenue.

Rose Hill is indeed on a hill. The sandstone chapel at the top of the hill is ninety feet higher than the entrance gate at Sandy Lane and Lancaster Avenue.

The sandstone used in the masonry of Rose Hill is similar to the sandstone prominent at three nearby landmarks: Top o’ Hill Terrace, the house and commercial building of gangster O. D. Stevens, and the estate of Paul Waples.

The sandstone used in the masonry of Rose Hill is similar to the sandstone prominent at three nearby landmarks: Top o’ Hill Terrace, the house and commercial building of gangster O. D. Stevens, and the estate of Paul Waples.

A cemetery is a city, albeit a silent one, populated by a city’s cross-section of humanity. Most of a cemetery’s residents are just ordinary folks who are remembered by only those who gathered at their grave to say goodbye.

A cemetery is a city, albeit a silent one, populated by a city’s cross-section of humanity. Most of a cemetery’s residents are just ordinary folks who are remembered by only those who gathered at their grave to say goodbye.

Rose Hill has almost thirty thousand such folks, which would make it the fourteenth most populous city in Tarrant County, comparable to Southlake.

As you will see, a cemetery that populous has a few residents who are famous.

And at least one who is infamous.

Among the folks who call Rose Hill “home” are:

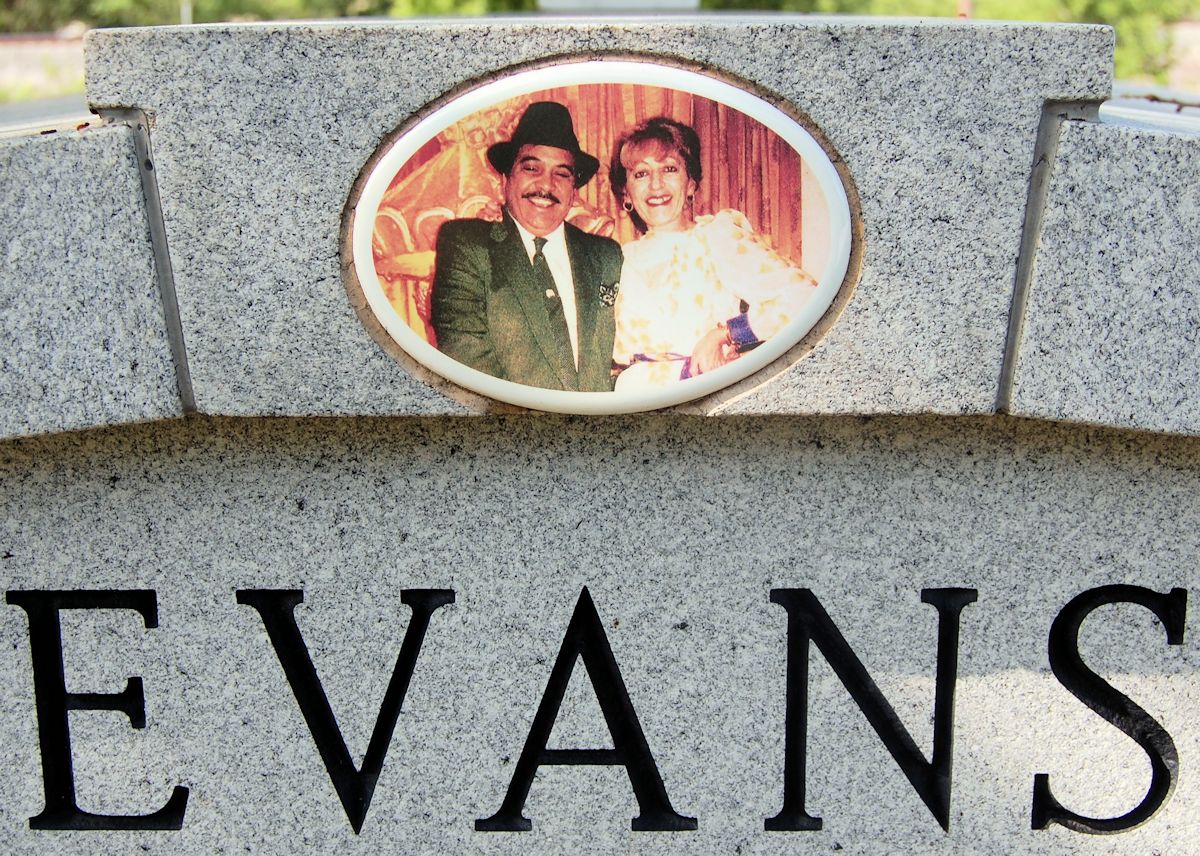

Because Rose Hill was opened well after photography was perfected, it has more tombstones with cameos than do older cemeteries in town.

Many of Rose Hill’s cameos are on the tombstones of members of the Evans Roma clan.

Quality Hill cattleman and capitalist Christopher Augustus O’Keefe built the Blackstone Hotel.

Quality Hill cattleman and capitalist Christopher Augustus O’Keefe built the Blackstone Hotel.

Former Paschal High School teacher Tom Huff was a best-selling author of romance novels.

Former Paschal High School teacher Tom Huff was a best-selling author of romance novels.

Even funeral directors die. James Raymond Meissner worked for Samuel David Shannon at Shannon’s funeral homes on the North Side and on the East Side. About 1945 Meissner bought Shannon’s East Side funeral home on Nashville Avenue and operated it as Meissner Funeral Home for more than thirty years.

Even funeral directors die. James Raymond Meissner worked for Samuel David Shannon at Shannon’s funeral homes on the North Side and on the East Side. About 1945 Meissner bought Shannon’s East Side funeral home on Nashville Avenue and operated it as Meissner Funeral Home for more than thirty years.

If anyone should feel at home at Rose Hill, it’s Major James Madison Handley, who once owned a plantation on the property and had planned to build a home for his sweetheart at the top of the hill. But she died before they could be married.

If anyone should feel at home at Rose Hill, it’s Major James Madison Handley, who once owned a plantation on the property and had planned to build a home for his sweetheart at the top of the hill. But she died before they could be married.

Paul Hollis was the inventor of Poly Pop, the first powdered soft drink mix.

Paul Hollis was the inventor of Poly Pop, the first powdered soft drink mix.

Monroe Odom was a Star-Telegram newsie for fifty-nine years.

Monroe Odom was a Star-Telegram newsie for fifty-nine years.

Harold Taft in 1949 became the first TV meteorologist west of the Mississippi and held that job at WBAP-TV for forty-two years.

Harold Taft in 1949 became the first TV meteorologist west of the Mississippi and held that job at WBAP-TV for forty-two years.

Band leader Bobby Peters was another pioneer TV personality in the early days of WBAP-TV.

Band leader Bobby Peters was another pioneer TV personality in the early days of WBAP-TV.

Imogene and Boyd Milligan operated the 7th Street and Poly theaters.

Imogene and Boyd Milligan operated the 7th Street and Poly theaters.

Charles Moss Davis was a civil engineer who specialized in construction of concrete buildings, including what he termed “apart-homes.”

Charles Moss Davis was a civil engineer who specialized in construction of concrete buildings, including what he termed “apart-homes.”

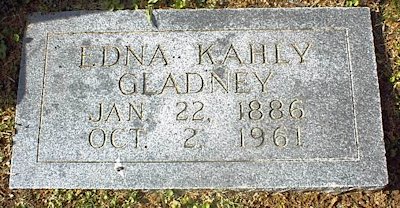

Edna Gladney was a childless woman who was a mother to many: Her adoption agency found homes for thousands of babies.

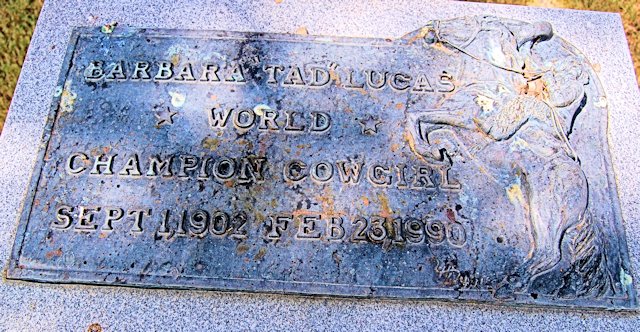

Tad Lucas was five-foot-one, but for a quarter-century no one stood taller in the saddle among female rodeo performers. She won virtually every major prize offered to women in rodeo, competing in trick riding, bronc riding, and relay racing.

Tad Lucas was five-foot-one, but for a quarter-century no one stood taller in the saddle among female rodeo performers. She won virtually every major prize offered to women in rodeo, competing in trick riding, bronc riding, and relay racing.

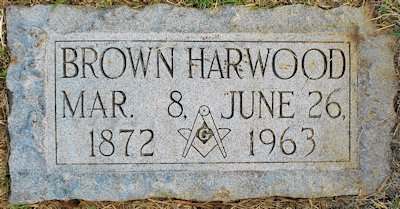

Fort Worth real estate agent Brown Harwood in 1922 was elected imperial klazik (vice president), the no. 2 man in the Ku Klux Klan national leadership.

Fort Worth real estate agent Brown Harwood in 1922 was elected imperial klazik (vice president), the no. 2 man in the Ku Klux Klan national leadership.

John Clay Kennedy was a man of many careers, most notable being a breeder of champion show horses and a founder of Globe Laboratories and Globe Aircraft Company.

A. C. Howerton was a Fort Worth police detective for thirty-one years. During that time he investigated many of the city’s most sensational crimes.

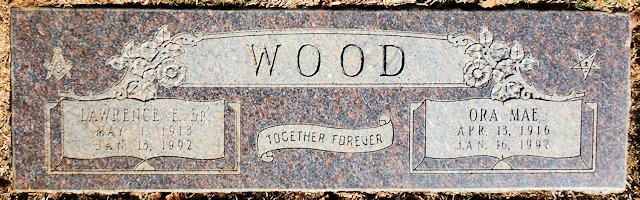

Another Fort Worth police officer, Captain Lawrence Wood, served on the force for forty-three years, mostly as a motorcycle officer. For years he and his Harley-Davidson led most of the city’s parades and funeral processions. He moonlighted at Carlson’s Drive-In Restaurant on South University Drive as the sheriff of Teentown. He lectured on traffic safety, headed the school district’s security program, and taught driver’s education. He also escorted visiting presidents, including Kennedy from and to Carswell Air Force Base in November 1963.

And that brings us to . . .

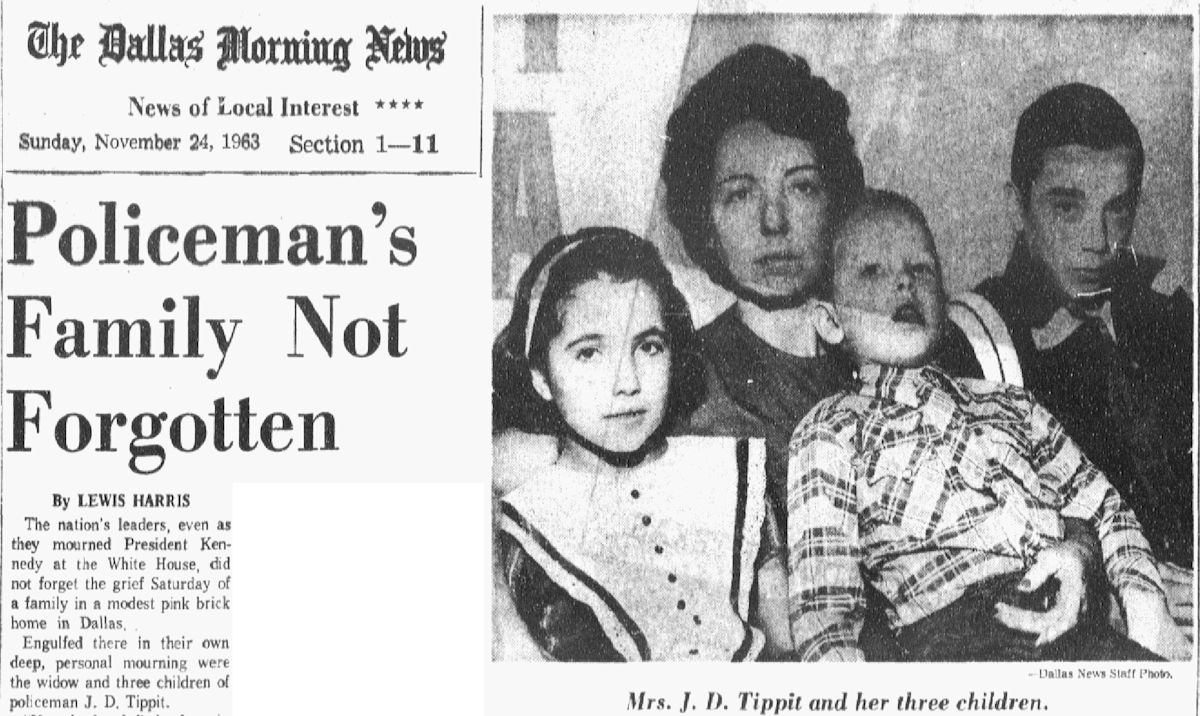

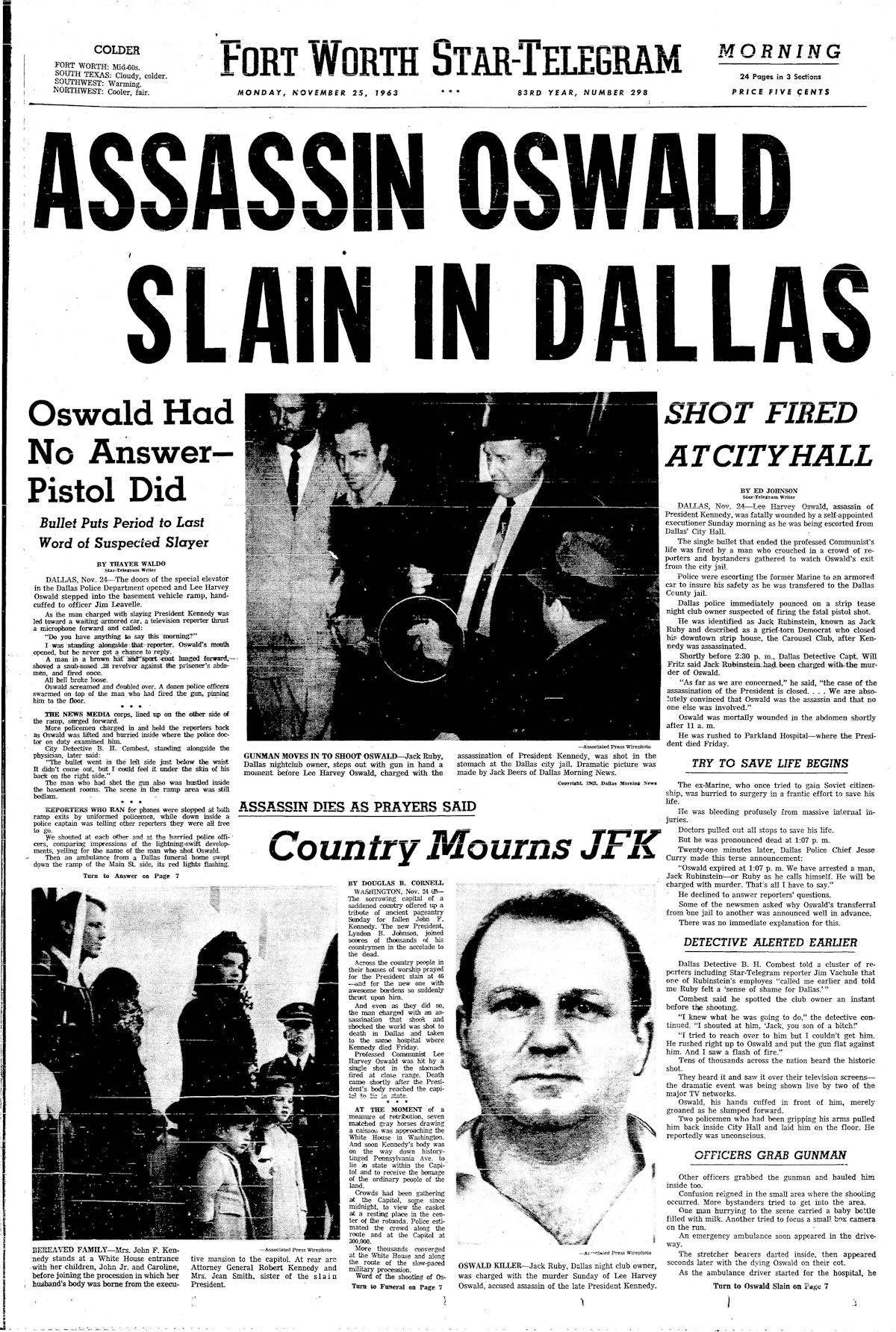

The afternoon of November 25, 1963 was a long one for our national psyche. Three funerals took place: President Kennedy was buried in Washington, D.C.; police officer J. D. Tippit was buried in Dallas; and Lee Harvey Oswald was buried in Fort Worth.

About fifty police officers were positioned around the perimeter of Rose Hill Cemetery to prevent any disorder as Oswald’s widow, their two young children, his mother, and his brother arrived at the cemetery, escorted by Secret Service agents and police.

About fifty police officers were positioned around the perimeter of Rose Hill Cemetery to prevent any disorder as Oswald’s widow, their two young children, his mother, and his brother arrived at the cemetery, escorted by Secret Service agents and police.

Oswald’s five family members were the only mourners at his funeral.

And that presented a problem for the reluctant funeral home director: no pallbearers.

So, he drafted seven of the seventy-five or so reporters who were present.

Some refused.

Among those who consented to carry Lee Harvey Oswald’s inexpensive wooden casket to the grave were writer Mike Cochran of Associated Press and writers Jon McConal, Jerry Flemmons, and Ed Horn of the Star-Telegram.

Among those who consented to carry Lee Harvey Oswald’s inexpensive wooden casket to the grave were writer Mike Cochran of Associated Press and writers Jon McConal, Jerry Flemmons, and Ed Horn of the Star-Telegram.

Reverend Louis Saunders of the Fort Worth Council of Churches spoke briefly at the gravesite.

“We’re not here to judge,” he said. “We’re here to lay this man away into the hands of an understanding God.”

Associated Press writer Mike Cochran recalls serving as a pallbearer on YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bxLmSOqk2gI

Fast-forward thirty-four years. In 1997 this tombstone was installed next to that of Lee Harvey Oswald.

Fast-forward thirty-four years. In 1997 this tombstone was installed next to that of Lee Harvey Oswald.

“Who the heck is Nick Beef?” curious people asked. Cemetery officials would not divulge who had bought the plot and tombstone. They would say only that no one was buried in the plot.

“Who the heck is Nick Beef?” curious people asked. Cemetery officials would not divulge who had bought the plot and tombstone. They would say only that no one was buried in the plot.

Those two facts created an instant mystery. Theories proliferated as journalists and assassination buffs sought the truth about Nick Beef, the man who wasn’t there.

Fast-forward another sixteen years. In 2013—the fiftieth anniversary of the assassination—Nick Beef finally, well, surfaced.