Engine trouble on the road is aggravating. Engine trouble in the sky is deadly.

At 5:05 a.m. November 22, 1950 B-36 44-92035 of the 26th Bomb Squadron of the 7th Bomb Wing took off from Carswell Air Force Base.

The giant six-engine bomber’s commander was First Lieutenant Oliver Hildebrandt, twenty-eight. He had a crew of fifteen men. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

The B-36 was embarking on a thirty-hour training mission that would include air-to-air gunnery, bombing, simulated radar bombing, and navigational training at Matagorda Island on the gulf coast three hundred miles away.

But within minutes of takeoff, flames erupted from the no. 1 engine. The flight engineer shut down the engine.

No big deal. As commander Hildebrandt later said, “because a B-36 flies fine on five engines.”

The B-52 cruised at an altitude of five thousand feet to the gunnery range on Matagorda Island. Upon arrival at 7 a.m. the plane’s gunners began practicing.

During the fourth gunnery pass over the island, Hildebrandt noticed that vibration from firing the 20mm cannons increased significantly. Soon after, the radar operator reported that vibration from the cannons was causing shorting between the components of the radar.

Then the liaison transmitter failed.

Then the guns in two turrets stopped firing.

Then the two gun turrets would not retract into the fuselage.

It was going to be one of those days.

And it wasn’t even 8 a.m. yet.

At 7:31 a.m. the no. 3 engine failed.

Now the B-36 had only one functional engine on the left wing, so Hildebrandt aborted the training mission and headed for Kelly Air Force Base at San Antonio—130 miles away.

The flight engineer soon realized that vibration from the cannons also had damaged the electrical systems that controlled the spark settings and fuel mixture of the engines.

The B-36 could not maintain its airspeed on just four engines. It descended one thousand feet and slowed to 135 miles per hour.

The pilot called for more power. The overtaxed engines responded by backfiring.

Kelly Air Force Base was under a cloud overcast at just three hundred feet and visibility of just two miles. The weather at Bergstrom Air Force Base at Austin was better, with scattered clouds at one thousand feet, broken clouds at two thousand feet, and visibility of ten miles. Carswell Air Force Base—home, sweet home—had the best weather of all, but it was 150 miles farther away than Bergstrom.

Meanwhile, air traffic control cleared the airspace below four thousand feet in front of the crippled B-36. Commander Hildebrandt was flying on instruments in thick clouds.

Because of the poor conditions at Kelly, Hildebrandt changed course from Kelly to Carswell, passing over Bergstrom Air Force Base on the way in case the B-36 could not reach Carswell.

The bombardier tried to drop the 1,500 pounds of bombs that the plane was carrying, but the bomb bay doors would not open.

And there was no way to dump fuel to reduce the weight of the plane.

Because the electrical systems controlling the spark settings and fuel mixture of the engines were damaged, flight engineers had to try to manually control the engines.

The high power demand on the engines caused their temperatures to rise to 500 degrees. The high temperature in turn caused the gasoline-air mixture in the cylinders to detonate prematurely, decreasing power still more.

By the time the B-36 reached Cleburne—just thirty miles from Carswell—the backfiring had worsened. Three engines were operating at 70 percent power and one engine at only 20 percent power.

The plane’s speed had dropped to 130 miles per hour.

As the bomber passed Cleburne, white smoke, oil, and metal particles were flying from the no. 5 engine. Twenty-one miles from Carswell Air Force Base engine no. 5 lost power.

Now the crew of B-36 44-92035 was trying to keep 140,640 pounds of metal in the air with three failing engines.

And the plane was carrying fuel and explosives.

The B-36 was flying at 125 miles per hour, just seven miles per hour above its stall speed. The plane was losing both altitude and airspeed.

Howard McCullough and W. Boeten were flying a DC-3 near Cleburne when they saw the B-36. They saw that two engines were feathered and one was on fire. They turned to follow the bomber.

North of Cleburne commander Hildebrandt ordered the crew to bail out.

Hildebrandt was the last man out. He set the B-36 to autopilot and aimed it at an open field ahead. He jumped when the bomber was less than one thousand feet above the ground. Hildebrandt had flown combat missions in Europe and the Pacific in World War II.

But this was his first bailout.

Hildebrandt and thirteen crew members suffered minor injuries.

Navigator Captain Horace Stewart had previously tried to get off flying status because he felt that the B-36 was dangerous. He was said to be nervous as the bailout began. He pulled his rip cord as he exited the escape hatch. His parachute opened and pulled him toward the no. 3 propeller. His head hit a blade of the propeller, killing him instantly.

Radar operator Captain James Yeingst was said to have been a bit giddy before he jumped. His parachute streamed after he pulled the rip cord but did not mushroom open until just before he hit the ground. He suffered fatal injuries.

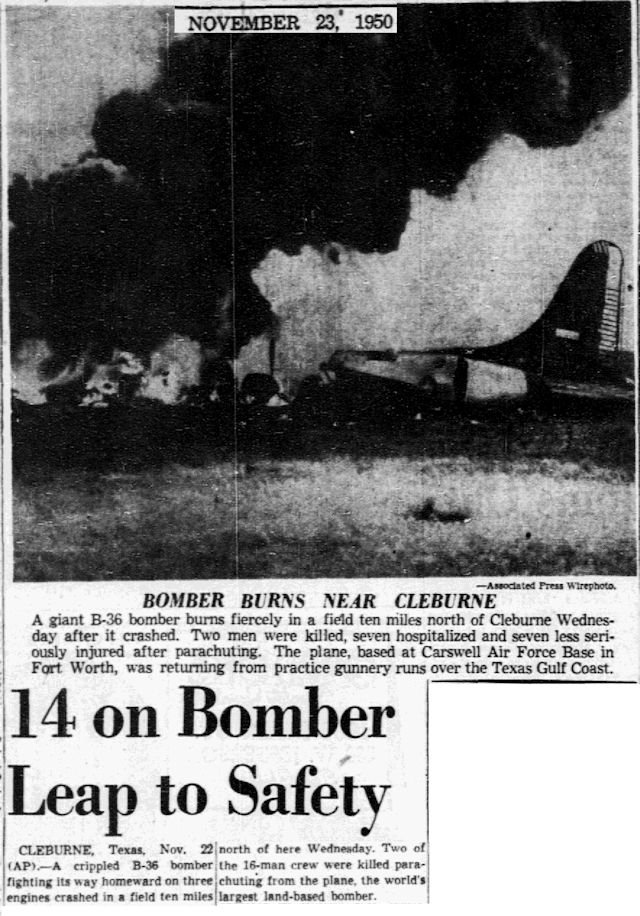

After commander Hildebrandt bailed out, the B-36 descended straight ahead in a nose-high attitude for a mile. At 9:50 a.m. it stalled, pitched nose down, and hit a field on Les Armstrong’s dairy fourteen miles from Carswell Air Force Base.

On the ground, the descent of the B-36 was witnessed by Buck Bell and his wife, who lived about six miles southwest of Crowley. Bell saw the crew members parachuting from the bomber but did not see it hit the ground about one mile north of his house.

James Bandy and his wife were on a road near Joshua when they saw the B-36 trailing smoke, flying in a nose-high attitude. They saw it hit the ground in a level attitude, raising a cloud of dust.

W. O. Doggett witnessed the bailout and crash from his home near Joshua. The B-36 hit the ground about two and a half miles from his house. He drove to the crash site in his pickup and helped the surviving crew members.

One eyewitness said the crippled B-36 landed so normally that he assumed the pilot was still at the controls.

The forward crew compartment of the plane folded underneath the fuselage. The tail section broke off, and the rear crew compartment separated from the fuselage as the airplane skidded eight hundred feet across the field.

The wreckage smoldered for a few minutes before a fire broke out in the no. 6 engine. The fifteen thousand gallons of remaining fuel consumed the forward fuselage and wings. People at the crash site were kept back by fire and exploding ammunition.

Note that the B-36 crash shared the Star-Telegram front page with the Harris car-bombing.

Note that the B-36 crash shared the Star-Telegram front page with the Harris car-bombing.

Yes, after flying 586 troubled miles, two men on board B-36 44-92035 had died just fourteen miles from “home.” But the death toll could have been far worse.

In recognition of that fact, soon after the crew was flown by helicopter back to Carswell Air Force Base, the crew’s squadron commander, Lieutenant Colonel William R. Calhoun, shook First Lieutenant Oliver Hildebrandt’s hand and said this to the twenty-eight-year-old who had just battled mechanical problems for 586 miles, got fourteen of sixteen men safely off the crippled plane, and set the plane’s autopilot to land 140,640 pounds of metal, fuel, and explosives in an unpopulated area:

“We’re putting you in for a promotion to captain first thing in the morning.”

I never knew about this crash. Thank you for this article. I do remember the B-36 as I believe one was permanently (sic) in front of Carter Field, later GSW. I was a stew for Ft. Worth’s Central airlines…and remember seeing that huge aircraft regularly…

Thanks, Jane. I have a post on the B-36s named for Fort Worth.