Oh, the ignominies you don’t figure on when you take up a life of crime.

Take, for example, Mrs. Helen Mecke, age nineteen. On March 24, 1953 she was having one of those shoulda-stayed-in-bed days. First she got arrested for bank robbery, then she threw herself from a moving police car and landed in jail. Then the police took her baby from her, she ripped her blouse, she tried to commit suicide, her husband found out what she had done, and then—how much can a person take?—the newspapers started calling her:

In fact, from Odessa to Ottawa newspapers hung that cruel nickname on her:

In fact, from Odessa to Ottawa newspapers hung that cruel nickname on her:

Shoulda stayed in bed.

It had all started so simply enough back in 1952. Helen and her husband Roy, an Air Force mechanic at Carswell, were in debt. They needed money.

Not unusual for a young couple. What was unusual was how Helen Mecke sought to solve the problem.

On November 25 Mrs. Mecke walked into the North Fort Worth State Bank.

She carried a blanket in her arms. People in the bank assumed that the blanket contained an infant.

One of those people was cashier E. G. Harris. He watched as the woman approached his window. She pulled a paper sack and a note from the blanket and passed them to Harris.

The woman did not speak.

Cashier Harris, understandably rattled, later told police that the gist of the note was: “I’m desperate . . . I need money to feed my baby.”

(Later news accounts said the note also claimed that the woman was deaf and dumb.)

Harris later said the woman led him to believe that the bundle contained a baby and a pistol, although she did not show him either.

Harris filled the paper sack with money and pushed it out to the woman. She tucked the sack of money and the holdup note into the blanket and walked toward the front door.

Bank vice president E. C. Steddum was entering the bank as Mrs. Mecke was walking out. He, too, assumed that a baby was wrapped in the blanket. He held the door open for the young mother as she left.

Harris later told police that the robber was a young blond woman wearing blue jeans rolled halfway up to the knees, white socks, a red scarf, and blue-rimmed eyeglasses.

Later, based on the robber’s appearance and MO, police suspected her in five recent robberies of liquor stores.

When Helen Mecke got home from the bank, her husband was still at the air base. She examined the contents of her blanket: a paper sack containing $600 ($5,700 today), a holdup note, a cap pistol, and a doll.

When Helen Mecke got home from the bank, her husband was still at the air base. She examined the contents of her blanket: a paper sack containing $600 ($5,700 today), a holdup note, a cap pistol, and a doll.

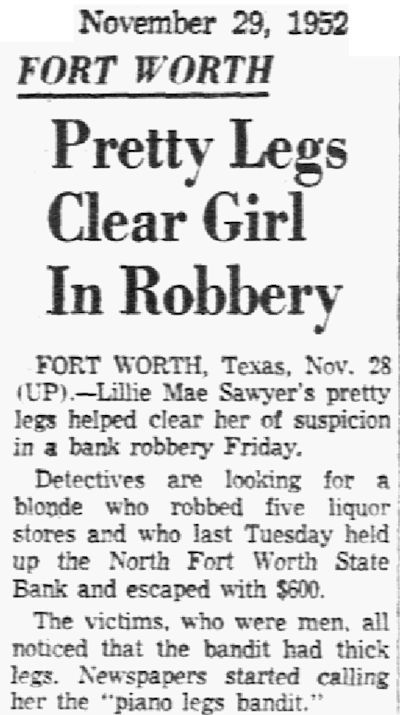

Based on the description of the woman who committed the liquor store robberies and the bank robbery, police sought a young blond woman who, male victims said, had “thick legs.” Police and newspapers began referring to the robber as “Piano Legs.”

Based on the description of the woman who committed the liquor store robberies and the bank robbery, police sought a young blond woman who, male victims said, had “thick legs.” Police and newspapers began referring to the robber as “Piano Legs.”

Three days after the bank robbery police arrested Lillie Mae Sawyer because she was a young blond woman. She denied being Piano Legs.

She also denied having piano legs.

In defense of her innocence she presented, as Exhibit A, her legs.

Police officers admitted that those were not piano legs.

In fact, said one detective, “They’re very pretty.”

Police investigated Ms. Sawyer’s alibi and released her.

Fast-forward to March 24, 1953. Helen Mecke was again wearing her robbery outfit: blue jeans rolled halfway up to the knees, white socks, a red scarf, and blue-rimmed eyeglasses.

She walked into the First National Bank of Handley carrying the blanket in her arms.

She stepped up to the window of cashier Mrs. G. L. DeVore, pulled a paper sack out of the blanket, and told Mrs. DeVore: “Fill this sack with 10s and 20s, or I’ll shoot the baby.”

“Oh, you wouldn’t do that,” Mrs. DeVore replied.

“Yes, I would. I just kidnapped it, and I don’t care about it,” Mrs. Mecke said.

This time the baby was real. Mrs. Mecke, who had been eight and a half months pregnant during the first bank robbery, had given birth just days later.

This time the blanket contained her son Chris.

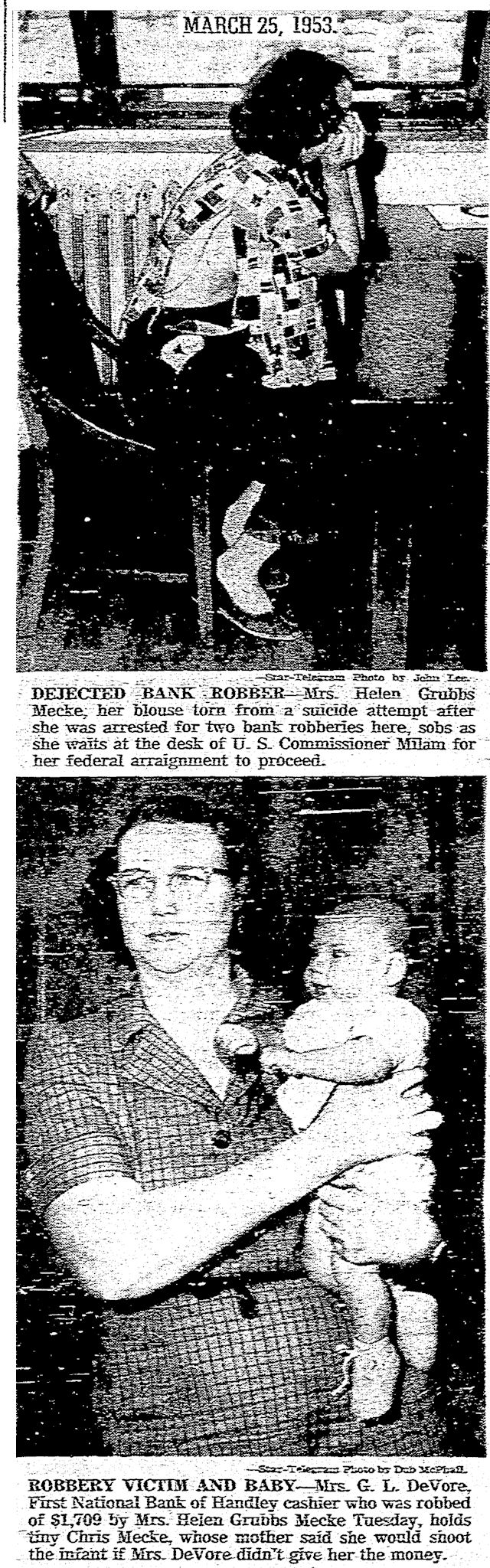

Mrs. DeVore later said that she then handed over a stack of bills and that mother and child left the bank. A group of men working outside the bank saw Mrs. Mecke walk to a car parked in an alley and speed away.

Mrs. DeVore immediately telephoned police and gave them a description of the robber.

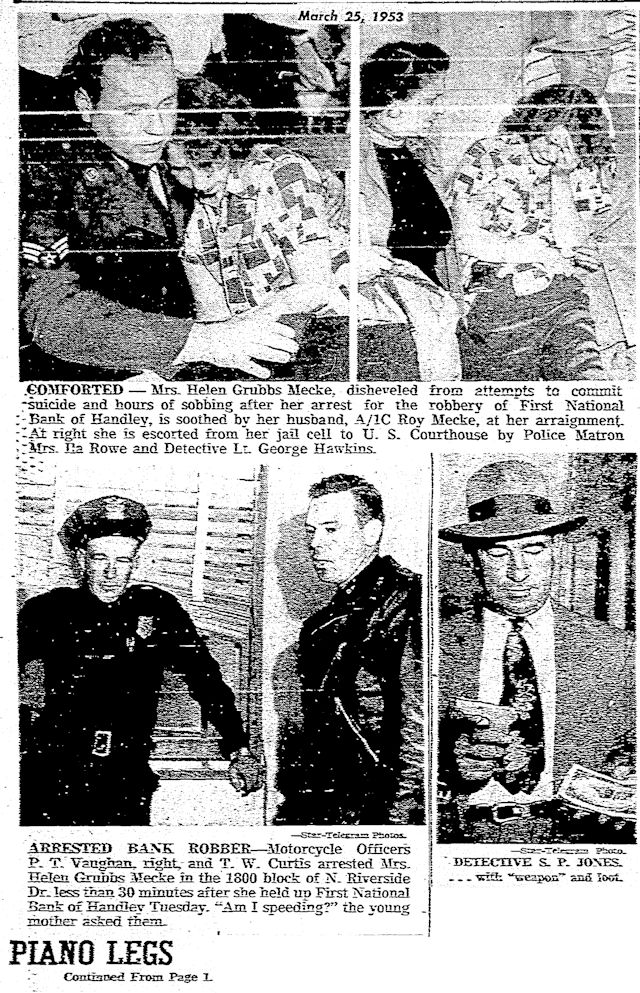

Motorcycle patrolman P. T. Vaughan, on duty in Riverside, heard the broadcast of the description of the robber and her car. Soon he saw the car on Riverside Drive and gave chase. Pulled over, Mrs. Mecke asked Vaughan if she had been speeding.

Inside her car officers found the baby, a cap pistol, and $1,700 ($16,000 today) taken from the bank.

As Mrs. Mecke was being driven to the police station she became frantic. She opened a door and jumped from the moving car.

“She skidded along for about thirty feet on her knees and then began running,” officer Vaughan later said. Two motorcycle officers who were following dismounted, chased her, and returned her to the patrol car.

At the police station, when separated from her baby she again became frantic, kicking and scratching and screaming, “Don’t take my baby!”

She fainted and was placed in a cell. There she ripped her blouse and tried to strangle herself with it.

She was brought under control, and the infant was placed in the care of a city welfare worker.

Mrs. Mecke sobbed and begged police not to tell her husband what she had done.

Her husband, when notified, was stunned to learn of his wife’s secret life of crime.

“She goes to church regularly. She has never smoked a cigarette or tasted liquor. She has never said a curse word. I can’t imagine what happened to her.

“She and the baby were healthy, and she seemed happy. Of course, like everyone else she worried about money—we weren’t millionaires, but we were making the payments.”

Mrs. Mecke admitted the two bank robberies, said she spent the money from the first robbery on doctor’s bills. She denied robbing any liquor stores.

As police questioned her about being the “piano legs bandit,” she asked detective John Dunwoody, “What does ‘piano legs’ mean?”

Dunwoody told a reporter, “I told her that I guessed it means she had extra thick ankles.”

“That’s what I thought,” Mrs. Mecke said sadly to Dunwoody. “I’ve got them all right. They’re big and fat.”

“You’ve got them,” Dunwoody agreed.

In addition to the “Piano Legs” nickname, in the coming days Mrs. Mecke would read newspaper accounts that described her as “disheveled,” “hysterical,” “chubby,” and “husky.”

Jeez, they didn’t talk this way about Dillinger.

Less than four hours after the second robbery Mrs. Mecke was arraigned on two charges of bank robbery before U.S. Commissioner Robert F. Milam.

Less than four hours after the second robbery Mrs. Mecke was arraigned on two charges of bank robbery before U.S. Commissioner Robert F. Milam.

When she saw that her husband was in the courtroom, she screamed, “No, no, no. Get him out of here.”

Even Commissioner Milam jumped on the band wagon. During Mrs. Mecke’s arraignment, he, too, referred to “piano legs.”

“Well, they got that right,” Mrs. Mecke said.

Because of her suicide attempt, after Mrs. Mecke was arraigned she was confined at the U.S. Public Health Service Hospital for observation. After thirty-four days of observation and testing, Mrs. Mecke was found to be “sane, knowing the difference between right and wrong and being legally and morally responsible.” The Star-Telegram reported that doctors found her to be “unusually intelligent.”

Because of her suicide attempt, after Mrs. Mecke was arraigned she was confined at the U.S. Public Health Service Hospital for observation. After thirty-four days of observation and testing, Mrs. Mecke was found to be “sane, knowing the difference between right and wrong and being legally and morally responsible.” The Star-Telegram reported that doctors found her to be “unusually intelligent.”

She was transferred back to jail and freed on bond.

“Out at the hospital they gave me a lot of tests,” she said. “I enjoyed them. I thought they were fun.” Mrs. Mecke said that during her month at the hospital she learned to play cards, worked crossword puzzles, and read.

“I love to read, too,” she said.

What type of reading?

“Oh, I like Shakespeare, Tolstoy. Just about anything except Erskine Caldwell. He writes too nasty.”

Mrs. Mecke pleaded guilty to the two bank robberies and in July was brought before District Court Judge T. Whitfield Davidson for sentencing.

Defense attorney Spencer Shropshire pointed out to Judge Davidson that the Meckes had bought a semifinished house and that Roy Mecke had turned over handling of financial affairs to his wife.

“She was paying the bills and taking care of the mortgage which they feared would be foreclosed, and I can truthfully say they were in dire financial circumstances [before the first robbery] in November of 1952,” Shropshire said.

Defense attorney Clyde Mays said, “She now understands the enormity of the things she has done.” Pointing out that Mrs. Mecke had robbed using only a cap pistol, Mays declared that statutes governing bank robbery were designed to stop “holdups by desperadoes with guns who are prepared to die in the attempt or snuff out the lives of those who thwart them.”

He said Mrs. Mecke was “trying to protect her home” by getting money because foreclosure was imminent and termed the robberies “foolish, extremely unbecoming but not serious, dangerous or criminal.”

Also present at the sentencing was Roy Mecke.

“Everybody wants to know what happened,” he said. “Nobody can figure out what happened, but I know what happened,” he told the judge with a choking voice. “Two people get married. They build a house and try to have a home. This is my fault. I left it on her shoulders. She didn’t rob it for herself. If anybody is guilty, it’s me.”

After listening to the arguments Judge Davidson said: “Many in this court are wondering if the judge will punish a woman like he would a man.” Davidson pointed out he had given men average penalties of fifteen to twenty years for bank robbery.

“If this was a young man I would perhaps give him ten years because of his tender years,” the judge said. “I do not think the intelligent and educated women of America would ask less, but I think the men would.”

Davidson sentenced Mrs. Mecke to five years in prison and admitted that he was lenient because of her gender.

Leaning forward, he said to Mrs. Mecke: “Young lady, if you want to rob banks, you should have been a boy.”

As Mrs. Mecke was waiting to be transferred to a women’s prison in West Virginia, she said she had been fearful as she had listened to Judge Davidson lecture her.

As Mrs. Mecke was waiting to be transferred to a women’s prison in West Virginia, she said she had been fearful as she had listened to Judge Davidson lecture her.

“I thought sure the judge was going to give me ten years on each robbery. Then when he started talking I just knew he was going to give me forty years. I’m lucky.”

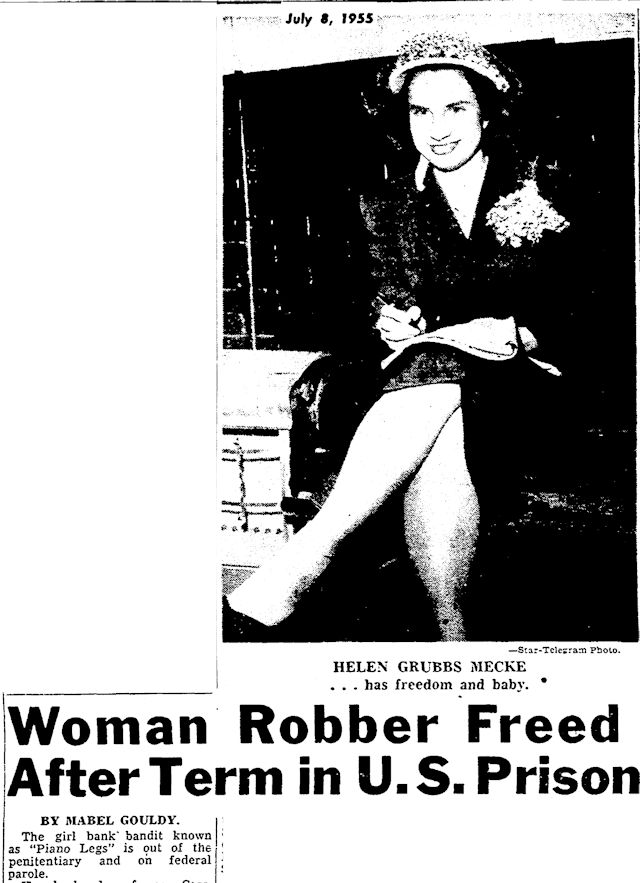

Fast-forward to 1955. Mrs. Helen Mecke had been “a good hand” working in the office at the federal penitentiary for two years.

In July she was paroled.

She got her freedom back, she got her baby back.

And she got her figure back.

She was now described as “trim” “neat,” and “attractive” by newspapers that two years earlier had described her as “disheveled,” “hysterical,” “chubby,” and “husky.”

Now they didn’t have a piano leg to stand on.

I have truly enjoyed this story about my mother in law. She later married again and became Helen Thornhill. She had 3 more children. However, I believe she went on to rob liquor stores in he Dallas area in th 70s as she was shot one night after work and the story I always heard about how she was shot was very dubious.

Thank you for making this so interesting and shedding light on what happened.

Thank you, Mary.