Just before 3 p.m. on September 27, 1927—one hour after Charles Lindbergh took off from Meacham Field to continue his nationwide tour—four men parked a black sedan in front of the North Side Coliseum on East Exchange Avenue. One man remained in the car with the engine running as the other three walked to adjacent Stockyards National Bank. Two of the men entered the bank; the third man remained outside the entrance.

A bank customer later said of the two men who entered the bank: “They came in waving guns and yelling for us to lie down.”

A bank customer later said of the two men who entered the bank: “They came in waving guns and yelling for us to lie down.”

Bank president Roy C. Vance later said: “I suppose there were about twenty people in the bank, including customers, when the men entered, drew guns, herded us to the rear and told us to lie down. I don’t know how many there were, three, four or five. I kept my eyes on the man who held a gun in my face.”

One customer and one bank employee who did not comply quickly enough with the orders were hit on the head with a pistol butt.

The bank had been warned that a robbery was planned and had hired off-duty police officers armed with sawed-off shotguns. But on September 27, because of Lindymania, every badge in town had been deployed elsewhere.

As the two crooks had entered the bank, employees were counting piles of money. The would-be robbers did not see the easy pickings in plain sight.

The Dallas Morning News wrote, “The usual bank money was being checked up by the tellers and was within easy reach of the robbers.”

The News noted that September 27 was a payday. The bank was flush with cash for stockyards and packing plant employees.

Bank president Vance later said: “The robbers evidently confused the ledger safe with the money safe. At any rate they searched the wrong safe and then, when the man who was holding a gun on us struck Charles Rabb, employee of the bank, on the arm with his pistol, which went off, they seemed to get panicky and fled without getting a cent. As they went out they sent several shots through the cashier’s window.”

Bank president Vance later said: “The robbers evidently confused the ledger safe with the money safe. At any rate they searched the wrong safe and then, when the man who was holding a gun on us struck Charles Rabb, employee of the bank, on the arm with his pistol, which went off, they seemed to get panicky and fled without getting a cent. As they went out they sent several shots through the cashier’s window.”

Vance said, “They seemed to get scared of their own cursing and shooting.”

J’Nell Pate in North of the River has a different account of some details: A delivery boy at the Renfro’s pharmacy a half-block from the bank started his three-wheel motorcycle. The engine backfired several times. What the gang’s lookout man at the bank entrance saw and heard made him think the delivery boy was a motorcycle policeman shooting at him. The lookout man alerted his two associates in the bank. They panicked and scrambled into the getaway car, knocked out the rear window so that they could shoot at any pursuers, and began firing wildly.

A witness notified a nearby policeman that a robbery was in progress.

“But I can’t leave my post,” the policeman said. “I have no car.”

A woman offered him the use of her car.

“But I can’t drive!” he said.

“I’ll drive,” the woman said.

For some reason the getaway car driver, rather than drive away from the bank down Exchange Avenue toward Packers Avenue, turned around and drove past the bank. As the crooks passed the bank they exchanged gunfire with armed citizens. No one was injured.

Pate writes that the carless policeman and his driver chased the getaway car north on Main Street, as did several other witnesses. Other people, including G. L. Wren, manager of the Renfro’s drugstore, shot at the getaway car as it passed. Witnesses said the glass of the rear window of the car had been shot out but were not sure if by the crooks or by their harassers.

The would-be robbers scattered nails and tacks onto the road behind them as they fled and escaped.

The botched robbery could well have been more tragic than comic: The next day an abandoned car believed to have been the getaway car was found. It contained a vial of nitroglycerin.

The botched robbery could well have been more tragic than comic: The next day an abandoned car believed to have been the getaway car was found. It contained a vial of nitroglycerin.

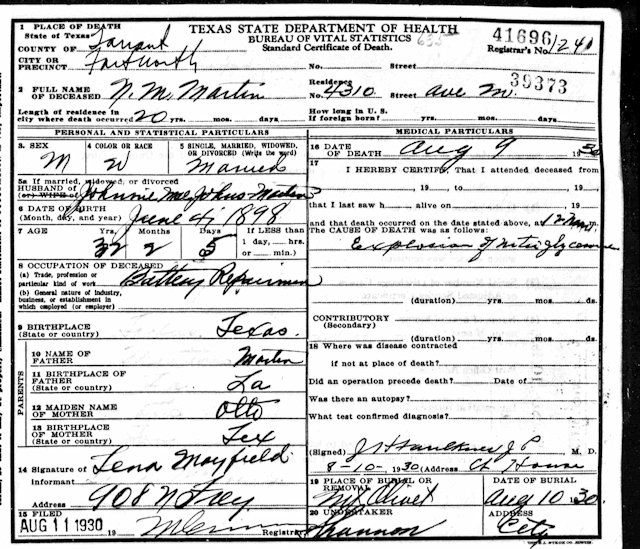

Which brings us to 1930. Same bank. In fact, one of the employees who had been working at Stockyards National Bank during the 1927 botched robbery was working there on the morning of August 9, 1930 when Nathan Monroe Martin walked into the lobby carrying a satchel. Martin was thirty years old, worked as a lead-acid battery repairman, lived at 4310 Avenue M in Poly.

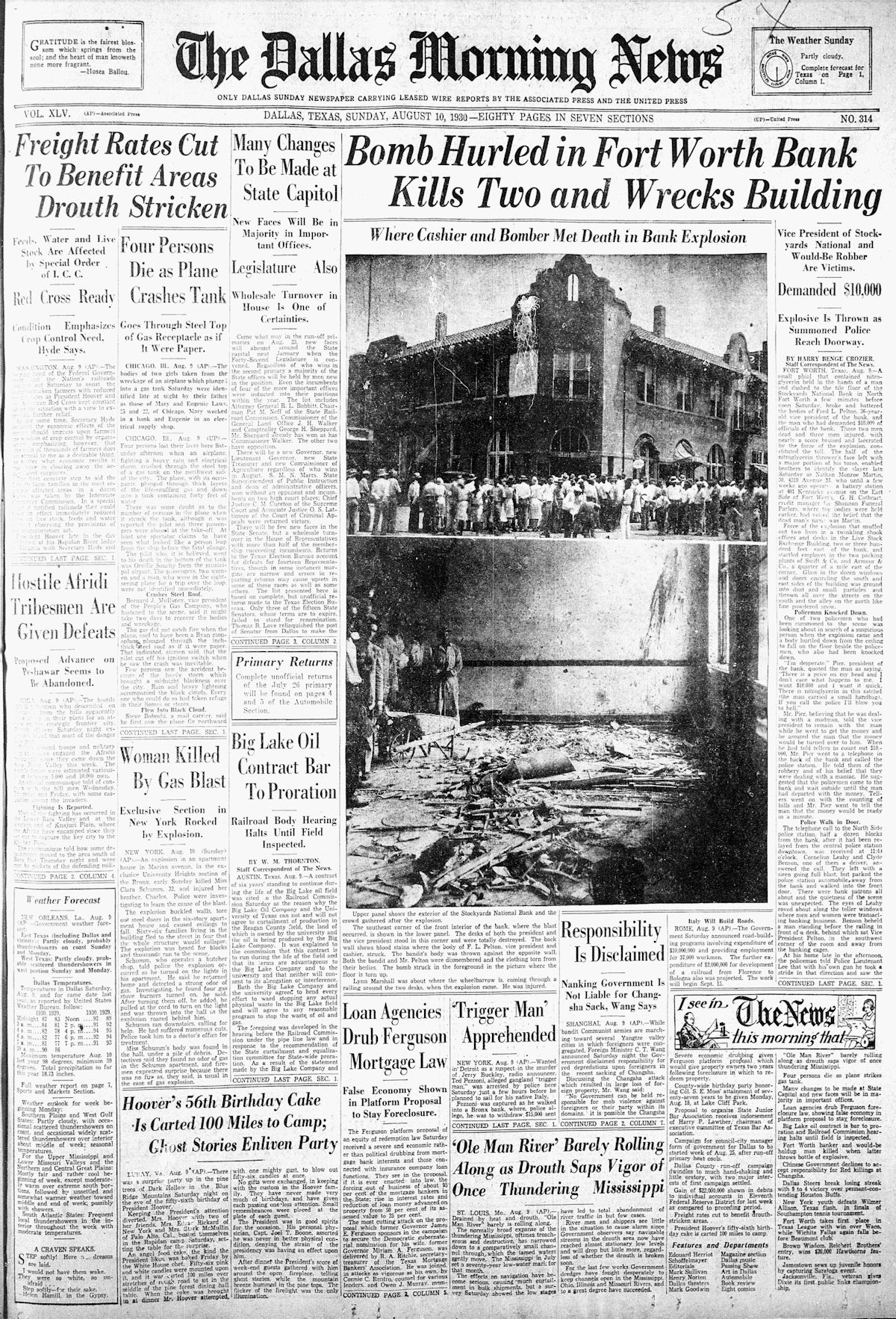

In the bank lobby Martin approached Fred L. Pelton, bank vice president and cashier. Pelton sat at his desk along the Exchange Avenue side of the building. Bank president W. L. Pier sat at his desk next to Pelton.

Martin said to Pelton: “I’m desperate—I want $10,000—I want it in currency. Don’t phone the police. There already is a price on my head. I don’t care what happens. There’s nitroglycerin in this bag!”

Pelton engaged Martin in conversation. Then Pelton turned to the president and said, “‘This man is desperate—he wants $10,000.’”

Pier went behind the bank cages and told the tellers to count out $10,000 in currency—but slowly. Then, out of sight of Martin, Pier telephoned the North Side police substation, located six blocks away.

Pier told police that he believed Martin was a madman. Pier asked that responding officers stay outside the bank and apprehend Martin when he came out with the money.

In the meantime, Pelton continued to talk with Martin, stalling as the money was counted and as police officers from the substation were driving to the bank.

Then Martin took a blank bank deposit slip from a table and wrote on it: “Fenix, Arizona sister living in that county.”

(Martin’s relatives later said he had no relative living in Arizona.)

Martin took from his satchel a .44-caliber pistol and a small glass vial of liquid.

He then repeated his demand for money and declared to Pelton, “I’ll blow you all to hell if I don’t get it.”

All of this was being done so discreetly that customers continued to transact business at teller cages, unaware of the drama playing out in the corner of the lobby.

But moments later two policemen walked into the bank. One of the officers later said that he looked around the lobby and saw nothing suspicious. The other officer later said that he saw Martin in the corner with Pelton. Martin was holding a pistol in one hand and a small glass vial in the other.

Martin watched the officer unholster his pistol. When the officer took one step toward Martin, Martin dropped the glass vial to the tiled floor.

Martin and Pelton were killed instantly, blown out of their shoes, their dismembered bodies hurled toward the ceiling and across twisted steel desks and splintered wooden chairs as window glass shattered, plaster fell from the ceiling, and smoke and paper money and bank documents floated through the air.

One police officer suffered temporary loss of hearing from the detonation, but no other serious injuries were suffered.

People a half-mile away heard the explosion. Trees one thousand feet away were stripped of leaves.

The bank, built in 1910, did not have a concrete foundation. The blast was concentrated downward, blowing open the wooden floor and blasting a four-foot-deep crater in the ground underneath. Had the foundation been concrete, one bank official said, the force of the blast would have been diverted outward and upward, probably resulting in greater damage and injury.

The damage was severe enough. As news of the calamity spread, people who had friends and family at the bank rushed to the scene. After they saw the condition of the building, some were not convinced when told that only two persons had been killed.

Nathan Monroe Martin had no police record, but police were well aware of him. Retired Fort Worth police sergeant and historian Kevin Foster writes that Martin had a history of disappearing and claiming “that he had been kidnapped and forced to commit crimes with known outlaws.” Police investigated Martin’s claims but soon learned to be skeptical. Martin’s widow said she believed that working with lead-acid batteries had neurologically impaired her husband.

Nathan Monroe Martin had no police record, but police were well aware of him. Retired Fort Worth police sergeant and historian Kevin Foster writes that Martin had a history of disappearing and claiming “that he had been kidnapped and forced to commit crimes with known outlaws.” Police investigated Martin’s claims but soon learned to be skeptical. Martin’s widow said she believed that working with lead-acid batteries had neurologically impaired her husband.

Police found Martin’s car parked near the courthouse. In the car was a note to his wife that read: “Forgive me for all I have ever done as I am in a position to where I can’t stand it any longer.” It was signed “Your Little Daddy.” A postscript read, “Here is all the money I have.” That amounted to $4.25 in cash and a checkbook with a $157 balance.

The car windshield had two bullet holes.

Bank president Pier ordered immediate repairs to the bank. Working through Sunday carpenters, plasterers, and glaziers repaired the splintered floor, replastered walls and ceilings, replaced window and door glass. Damaged desks and chairs were replaced.

On Monday morning Stockyards National Bank opened for business as usual, looking as if nothing had happened.

Except that on one desk along the Exchange Avenue side of the building lay a floral wreath.

(Thanks to retired Fort Worth police sergeant and historian Kevin Foster for his help.)

Other bank robberies gone awry:

Suitable for Framing: He Was Banking on the Picture-Perfect Crime

Boyce House (Part 1): “Santa Claus, Why Did You Rob That Bank?”

Posts About Crime Indexed by Decade

I just ordered your book “Lost Fort Worth”

Im excited to read more about this and other things.

Thank you for doing such amazing research and attention to detail.

Thanks for visiting this site. Unfortunately the author, Mike Nichols, has passed away. We are currently working to find a solution to best preserve this informative website.

My grandfather was WLPier he was lucky that day

Wow. Your grandfather went home from work that day with a story to tell the rest of his life.