In thirty-one years the Ace saw it all. Lust, greed, envy, wrath. His career as a Fort Worth police detective was a tour of the seven deadly sins.

Other Fort Worth police officers called Arthur Conway Howerton “the Ace” partly because of his “A. C.” initials but mainly because he was an ace detective.

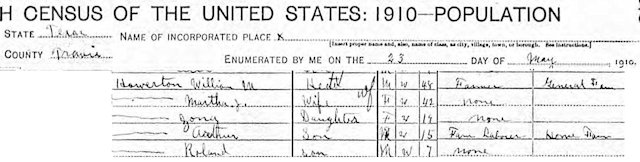

Howerton was born into a farming family in Williamson County in 1895. By 1910 the family was farming in Travis County. Now A. C. had a younger brother, Roland.

Howerton was born into a farming family in Williamson County in 1895. By 1910 the family was farming in Travis County. Now A. C. had a younger brother, Roland.

In 1917 A. C. and his wife moved to Denton County, where they continued to farm. Soon they had three children. He later recalled: “We were about to starve to death—farming was rougher than a cob.” So, in 1925 he put down the plow and pinned on the badge, becoming a Denton County deputy sheriff.

A. C. and brother Roland moved to Fort Worth about the same time in 1929 and became policemen. Roland lived in Poly in the beginning. A. C. lived his entire career in a modest house on Millet Street in Poly.

A. C. was promoted to the rank of detective in 1931.

But whereas Roland would work his way up to the rank of chief of police, A. C. stopped taking exams for promotion after he became a detective.

He had found his calling.

Elston Brooks, who was a Star-Telegram police reporter before becoming an entertainment columnist, recalled Howerton: “I can still see him coming down to headquarters as early as 5 a.m. on mornings when it was raining. ‘A good day to catch wanted men, m’boy,’ he’d say, rubbing his big hands briskly in the gloomy dawn. ‘Those ol’ thieves just love to turn over and go back to sleep on rainy mornings—and it’s so much easier to catch ’em when they’re asleep.’”

Star-Telegram editor Phil Record, who also been a police reporter during Howerton’s career, recalled that interrogation was Howerton’s specialty. Howerton was an imposing presence in an interrogation room: six-foot-six and 245 pounds. But he didn’t throw his weight around.

Howerton didn’t believe in physical force or pressure.

“It’s unjust and can only hurt a strong case,” he said. “Early in my life I learned nothing beats kindness—there’s an old saying you can catch more flies with sugar than with vinegar.”

Howerton used sympathy and reasoning.

Many a criminal too hardened to be broken by relentless interrogation discovered that Howerton had sympathized him into talking himself right into a cell.

For example, Howerton once interrogated an unusually tough murder suspect. Because the suspect was a three-time loser Howerton knew he wouldn’t crack under routine questioning. So, Howerton began taking the suspect to a cafe near the city jail and feeding him a hot meal once a day. After several hot meals instead of the jail’s cold baloney sandwiches the suspect began to want to discuss the case, only to have Howerton change the subject. Finally the suspect could stand it no more and over a hot meal blurted out a full confession.

“I never had to mention the case to him once,” Howerton recalled.

During an interrogation Howerton also used his “touch system.”

“It’s amazing the number of confessions I’ve secured by just gently placing my hand on a man’s shoulder or knee,” he said. “When a man finally wants to tell the truth he becomes very nervous. I always watch the palms—when they start to sweat I know the moment of truth is near. At this point I lay my hand on the suspect and ask him to unload his troubled conscience.”

One time, Brooks recalled, Howerton “came back to headquarters at 3 a.m. and sat in the cell with a suspect who was just about ripe to talk. The man was so impressed with A. C.’s courtly manner, he said he’d confess if he could hold A. C.’s hand. Howerton held his hand, and between tears another case was cleared up.”

“That’s the easy part of this work,” Howerton said once.

Howerton didn’t confine his powers of persuasion to the interrogation room. When confronted by an armed suspect in the field, Howerton operated on this theory: If a gunman doesn’t shoot you on sight, you’ve got a good chance of talking him out of his weapon. “But,” he said, “you’ve got to talk fast.”

During his career Howerton investigated 750 murders and uncounted rapes, suicides, and robberies. He talked hundreds of suspects into prison—and more than a dozen into the electric chair.

From the early 1930s to the early 1960s Howerton investigated many of Fort Worth’s most sensational crimes.

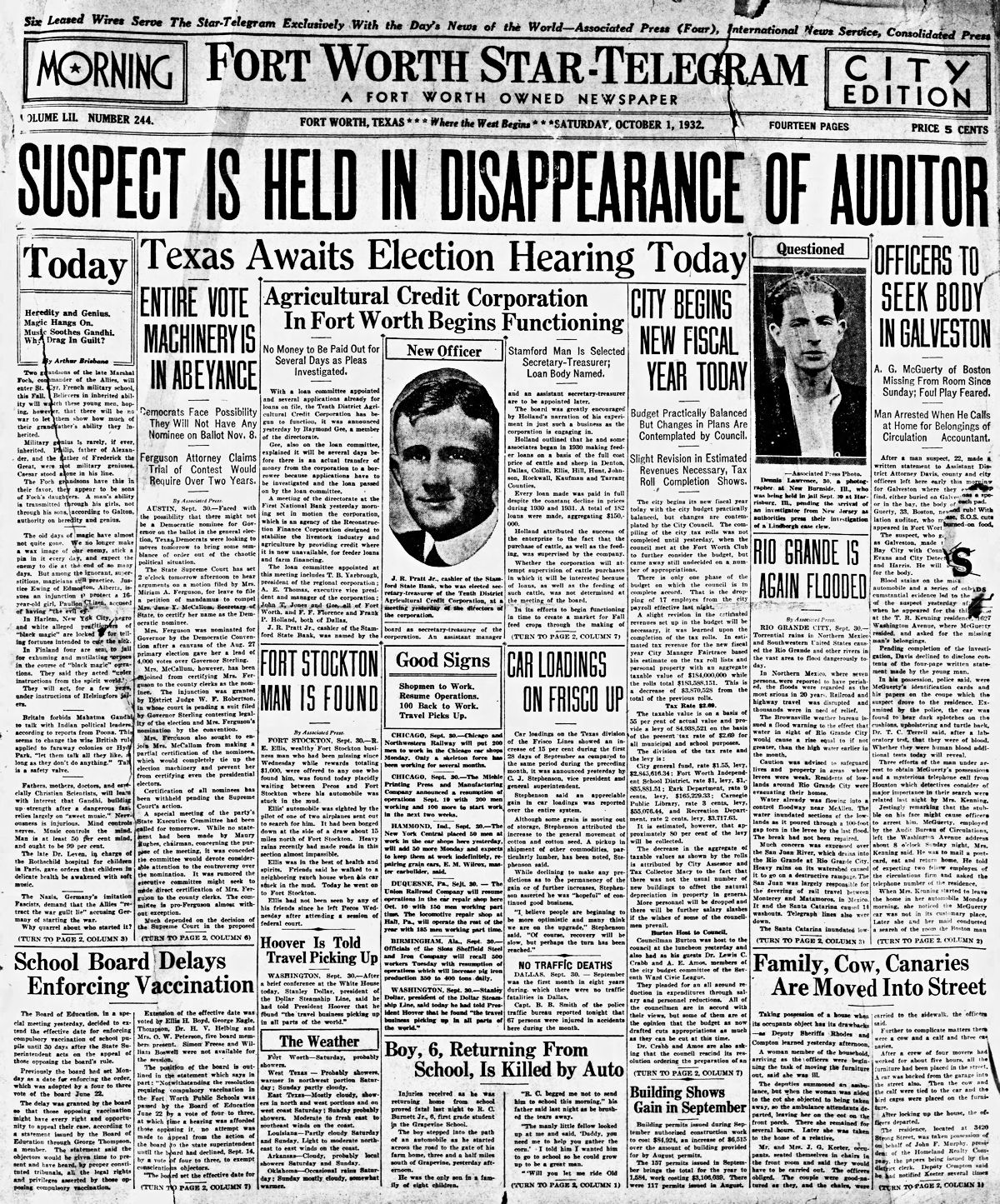

Howerton’s first murder case came in 1932 when William Raymond Ryals murdered newspaper auditor A. G. MacGuerty on Cooks Lane and buried the body in a shallow grave on the beach in Galveston.

Howerton’s first murder case came in 1932 when William Raymond Ryals murdered newspaper auditor A. G. MacGuerty on Cooks Lane and buried the body in a shallow grave on the beach in Galveston.

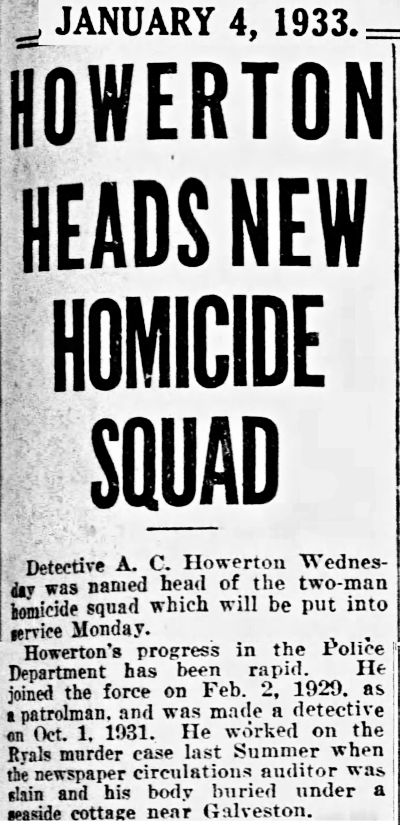

Howerton used his low-key interrogation method to get a confession from Ryals, who was later convicted. Three months later Howerton was promoted to head of the police department’s new homicide squad.

Howerton used his low-key interrogation method to get a confession from Ryals, who was later convicted. Three months later Howerton was promoted to head of the police department’s new homicide squad.

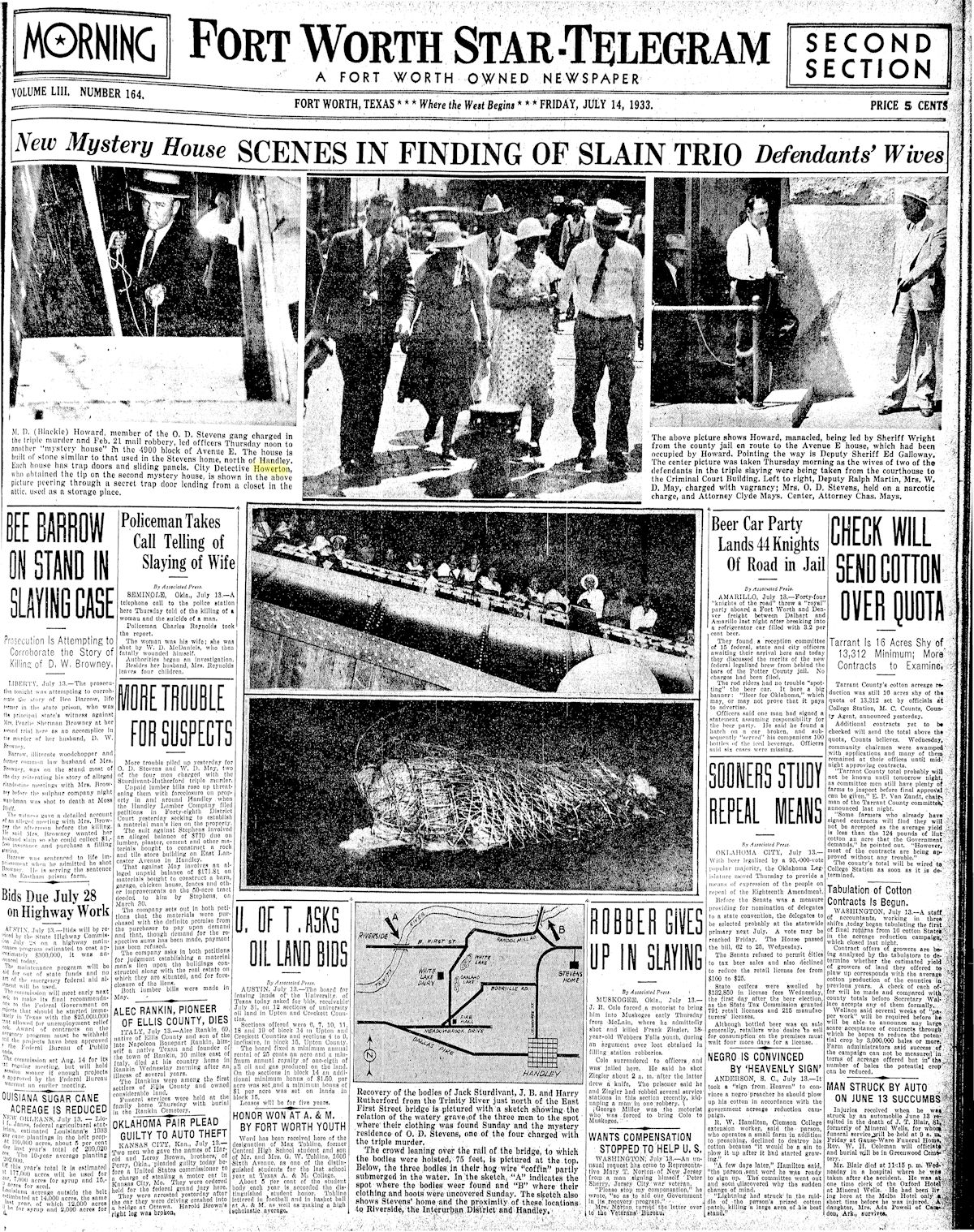

Later in 1933 Howerton worked another big case: The O. D. Stevens robbery and triple slaying. The front-page photo shows Howerton looking through a trapdoor in Stevens’s “mystery house” on Avenue E in Poly.

Later in 1933 Howerton worked another big case: The O. D. Stevens robbery and triple slaying. The front-page photo shows Howerton looking through a trapdoor in Stevens’s “mystery house” on Avenue E in Poly.

“It was the biggest murder case I ever worked on and the most spectacular crime in Tarrant County’s history,” Howerton later said.

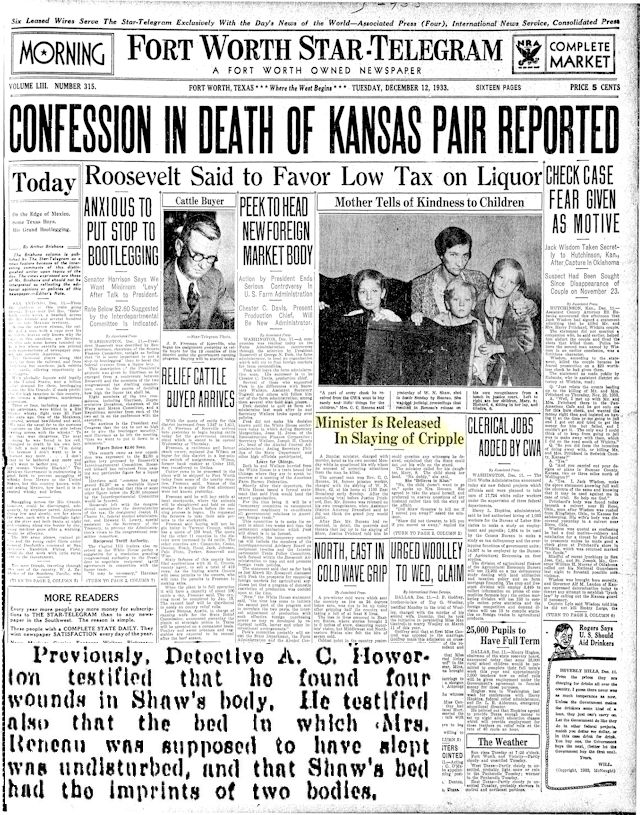

Also in 1933 Howerton investigated a homicide in which C. C. Reneau, a Baptist preacher, killed W. N. Shaw as Shaw was buckling on his artificial leg. Reneau accused Shaw of being too attentive to Reneau’s wife. Mrs. Reneau testified that she had slept in her own bed on the night of the killing. But Howerton testified that the wife’s bed had not been slept in but that Shaw’s bed showed the impressions of two bodies. Reverend Reneau cited the unwritten law as his defense and was no-billed.

Also in 1933 Howerton investigated a homicide in which C. C. Reneau, a Baptist preacher, killed W. N. Shaw as Shaw was buckling on his artificial leg. Reneau accused Shaw of being too attentive to Reneau’s wife. Mrs. Reneau testified that she had slept in her own bed on the night of the killing. But Howerton testified that the wife’s bed had not been slept in but that Shaw’s bed showed the impressions of two bodies. Reverend Reneau cited the unwritten law as his defense and was no-billed.

In 1936 Howerton investigated the slaying of Ross Turner by Turner’s estranged wife, Dr. Grace Humphreys Hood. Dr. Hood had shot Turner to death when he threatened her with a surgical knife in her office in the Medical Arts Building. Dr. Hood was no-billed by a grand jury. (Dr. Hood later lived in the big stone house on Foard Street.)

In 1936 Howerton investigated the slaying of Ross Turner by Turner’s estranged wife, Dr. Grace Humphreys Hood. Dr. Hood had shot Turner to death when he threatened her with a surgical knife in her office in the Medical Arts Building. Dr. Hood was no-billed by a grand jury. (Dr. Hood later lived in the big stone house on Foard Street.)

In May 1939 Howerton investigated an exchange of gunfire between three men who disagreed on the issue of whether white homeowners should sell homes to African Americans on the near East Side. That issue would culminate on Juneteenth when a mob of about five hundred whites forced the African-American family of Otis and Mattie Flake out of their house and vandalized it. (Among the children forced out of that house was Opal Lee, who today is called the “grandmother of Juneteenth.”)

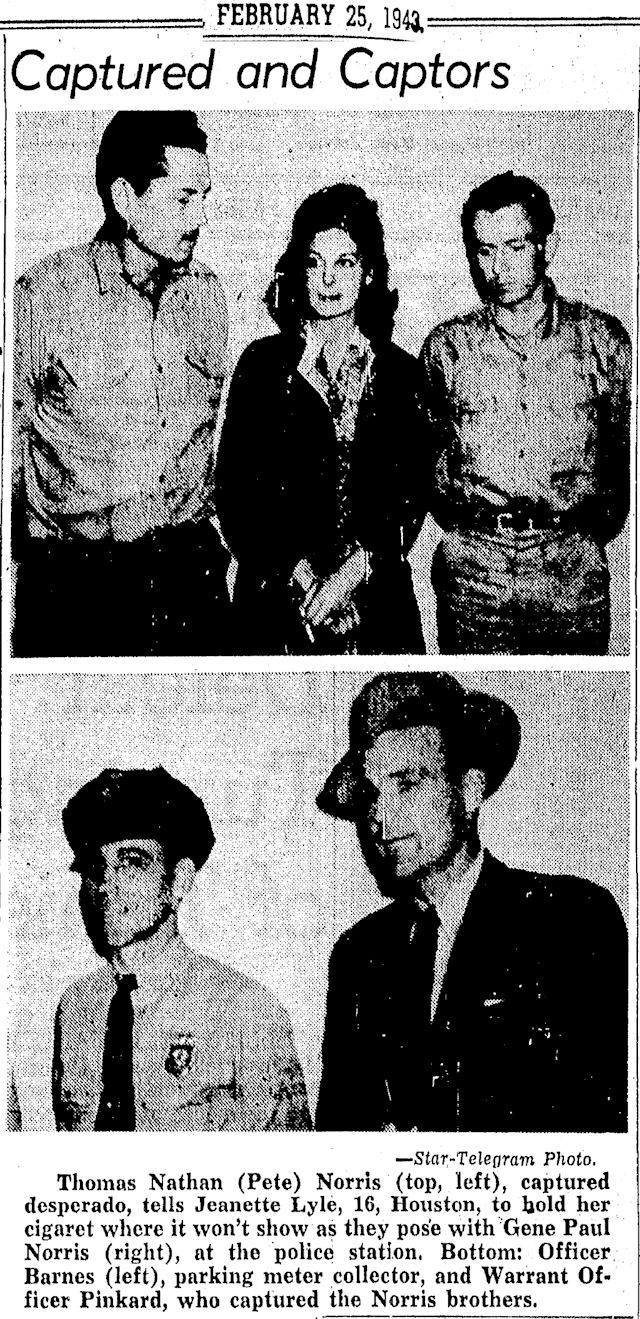

In 1943 Howerton took part in the high-speed rural police chase that resulted in the capture of career criminals Thomas Nathan (“Pete”) Norris and brother Gene Paul Norris.

In 1943 Howerton took part in the high-speed rural police chase that resulted in the capture of career criminals Thomas Nathan (“Pete”) Norris and brother Gene Paul Norris.

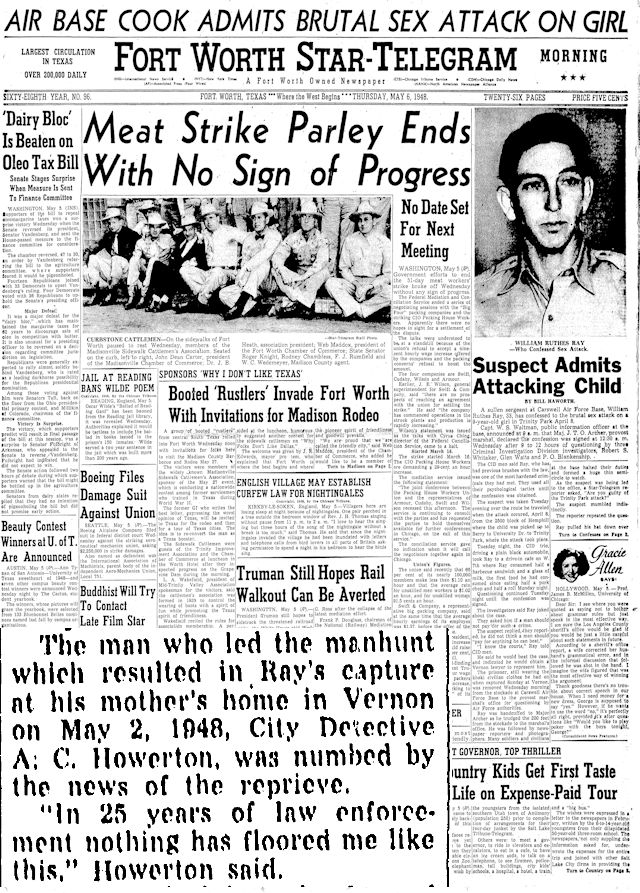

In 1948 Howerton led the manhunt that ended with the capture of William Ruthes Ray, who had raped an eight-year-old girl in Forest Park. Ray was convicted and sentenced to death. When the parents of the victim asked that Ray’s sentence be commuted to life imprisonment, Howerton was “floored.” The parents later withdrew their request for commutation, and Ray died in the electric chair.

In 1948 Howerton led the manhunt that ended with the capture of William Ruthes Ray, who had raped an eight-year-old girl in Forest Park. Ray was convicted and sentenced to death. When the parents of the victim asked that Ray’s sentence be commuted to life imprisonment, Howerton was “floored.” The parents later withdrew their request for commutation, and Ray died in the electric chair.

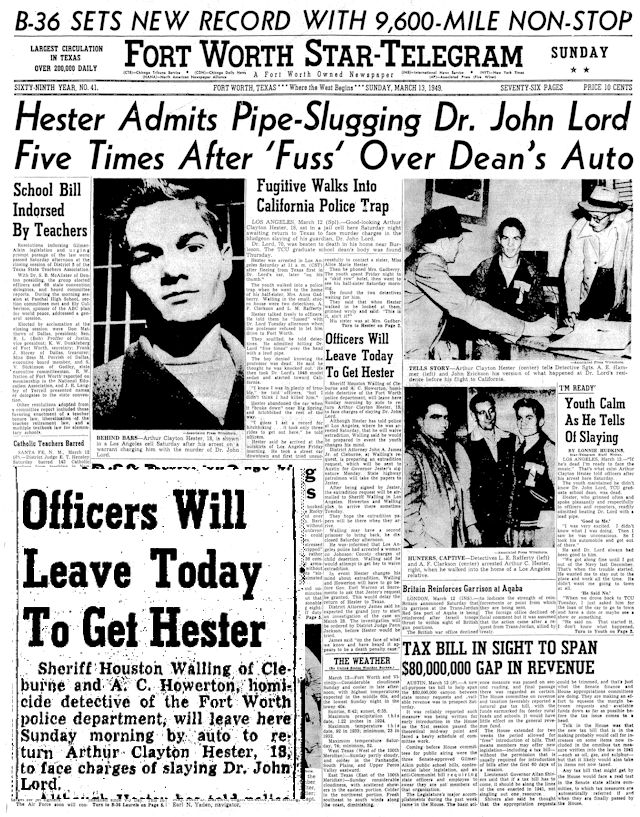

Howerton investigated the beating death of Dr. John Lord, dean of TCU’s graduate school and head of the social sciences department, at his Johnson County farm in 1949. Lord’s ward, Arthur Clayton Hester, eighteen, was sentenced to fifty years in prison.

Howerton investigated the beating death of Dr. John Lord, dean of TCU’s graduate school and head of the social sciences department, at his Johnson County farm in 1949. Lord’s ward, Arthur Clayton Hester, eighteen, was sentenced to fifty years in prison.

Also in 1949 when a grandmother, mother, and two children were found dead in a house in Riverside, Howerton quickly concluded that the grandmother had killed her daughter and two grandchildren and then killed herself.

Also in 1949 when a grandmother, mother, and two children were found dead in a house in Riverside, Howerton quickly concluded that the grandmother had killed her daughter and two grandchildren and then killed herself.

Elston Brooks recalled watching Howerton at the crime scene:

“I remember going with him one spring morning into a house of horror, where each glance into the next room produced another body. Police, summoned by a suspicious neighbor, had to break into the home because both screen doors were latched from the inside, and all window screens were latched. Or so it was believed at the time. In one room we found an elderly woman shot to death through the head. A pistol lay near her hand. I ducked around a corner to phone in the initial fact that it looked like a suicide. I passed a second bedroom door and was startled to see a younger woman lying in her bed, also slain with a head shot. There was one more bedroom down the hall before I could get to the phone. In it lay two children, 6 and 8, both shot to death. Obviously, since the house was locked from the inside, the older woman had slain her daughter and two grandchildren and then taken her own life. But Howerton had discovered one small window that didn’t have a screen latch. And the window was up. A killer could have planted the gun near the old woman, and . . . No one else had even noticed the screen was without a latch. But Howerton had, and it nagged at his mind. But he also saw something else. ‘Step here, m’boy, and witness something,’ he said to me. There, on the slanting window sill, lying flush against the latchless screen, was one of the ejected shell casings from the murder weapon. Howerton gently pushed open the screen. The casing rolled down the slanted sill and dropped on the ground outside.

“‘And that, m’boy,’ he said, ‘is how we know no one left this house after the shooting began.’”

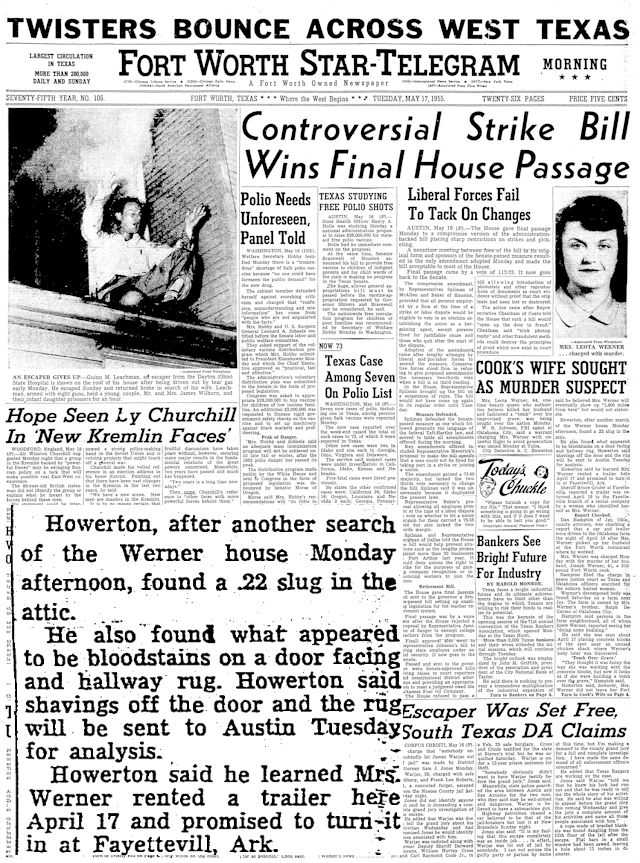

Howerton investigated the strange case of Joseph and Leota Werner. In 1955 Joseph, a three hundred-pound short-order cook, disappeared. By the time his badly decomposed body was found in a shallow grave in Oklahoma, Leota, too, had disappeared. And she stayed that way for six years.

Howerton investigated the strange case of Joseph and Leota Werner. In 1955 Joseph, a three hundred-pound short-order cook, disappeared. By the time his badly decomposed body was found in a shallow grave in Oklahoma, Leota, too, had disappeared. And she stayed that way for six years.

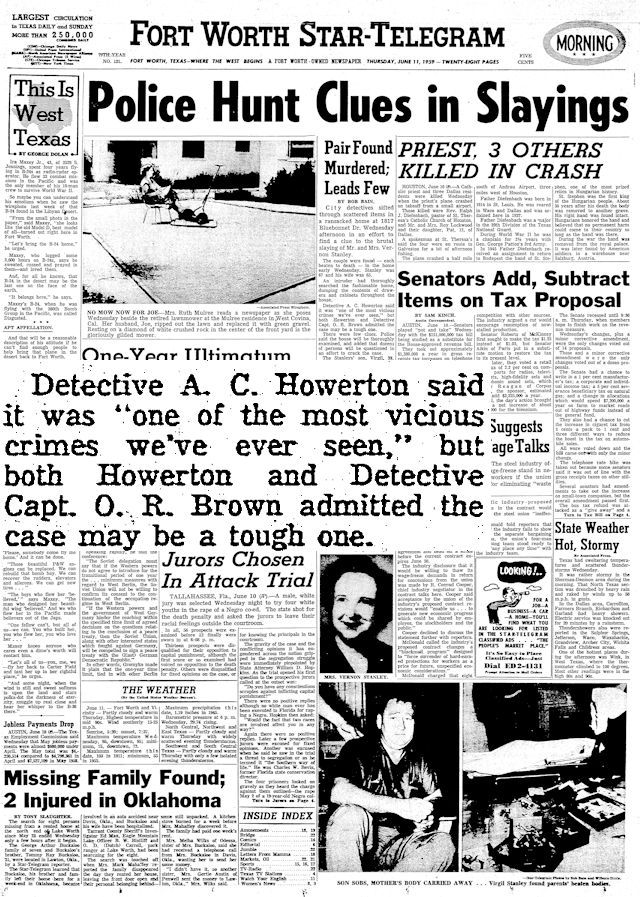

In 1959 Mr. and Mrs. Vernon Stanley were found beaten to death in their home in Oakhurst. Howerton suspected robbery as the motive, although a $1,000 ring remained on Mrs. Stanley’s finger. Pictures on walls had been disturbed as though the intruders were looking for a wall safe.

In 1959 Mr. and Mrs. Vernon Stanley were found beaten to death in their home in Oakhurst. Howerton suspected robbery as the motive, although a $1,000 ring remained on Mrs. Stanley’s finger. Pictures on walls had been disturbed as though the intruders were looking for a wall safe.

Howerton said the Stanley murders were the most vicious he ever investigated.

“It was such a heinous crime that even the killers had to cover the bodies while they ransacked the house,” he recalled. “I’d crawl across Texas on my belly to catch the man who did it.”

In the late 1940s and 1950s, during Fort Worth’s gangland era, Howerton investigated the crimes by—and gangland slayings of—triggermen and car-bombers:

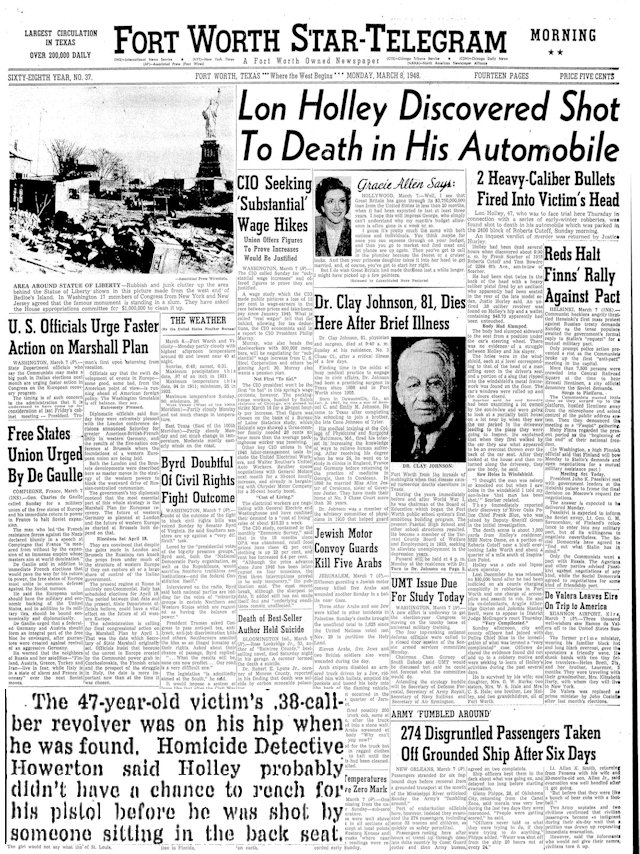

In 1948, one night just before gangster Lon Holley was to stand trial for six robberies Holley received a phone call. After receiving the call Holley left his house, telling his wife he was going to meet a man who would take him to see another man. Holley told his wife that if he was not back by midnight, “You will know something has happened.”

In 1948, one night just before gangster Lon Holley was to stand trial for six robberies Holley received a phone call. After receiving the call Holley left his house, telling his wife he was going to meet a man who would take him to see another man. Holley told his wife that if he was not back by midnight, “You will know something has happened.”

Something happened: Holley was “taken for a ride” in his own car and killed less than a mile from his house.

Howerton theorized that gangster Jim Thomas (see below) had killed Holley because Holley knew too much about Thomas’s criminal activities. But police did not have enough evidence to arrest Thomas in the Holley murder.

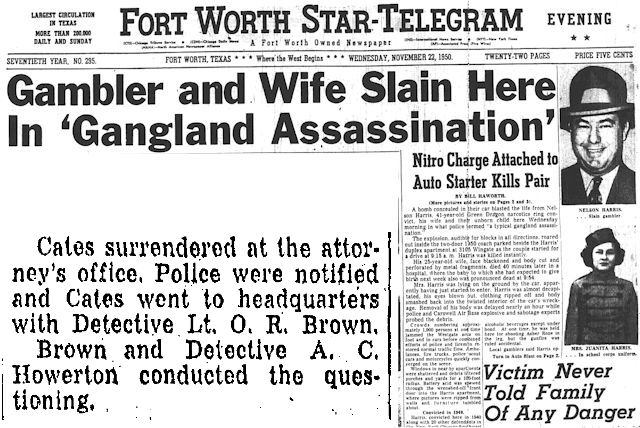

Two years later when gambler Nelson Harris, his wife, and unborn child were killed in a car-bombing at their home on the near West Side, among the “usual suspects” Howerton questioned was gambler Frank Cates.

Two years later when gambler Nelson Harris, his wife, and unborn child were killed in a car-bombing at their home on the near West Side, among the “usual suspects” Howerton questioned was gambler Frank Cates.

No one was ever convicted of the Harris car-bombing.

In 1956 Cates survived his own bombing. He was sitting in his gambling house just off Jacksboro Highway, counting money, when the phone rang. Cates picked up the receiver, and the house exploded. Under the house police found wires that ran 250 feet down Jacksboro Highway. Police suspected that one man had phoned Cates from a telephone on the highway and that another man in a car nearby had detonated the bomb when signaled by the first man.

A few weeks later Cates heard his phone ring again. Tempting fate, he answered. Just as Lon Holley had done, Cates told his wife he had to go meet a man. Police found Cates’s shotgunned body in his car on a country road.

A few weeks later Cates heard his phone ring again. Tempting fate, he answered. Just as Lon Holley had done, Cates told his wife he had to go meet a man. Police found Cates’s shotgunned body in his car on a country road.

No one was ever convicted of the Cates murder. Most of the usual suspects in gangland killings were themselves killed by other gangsters before the law could catch up with them.

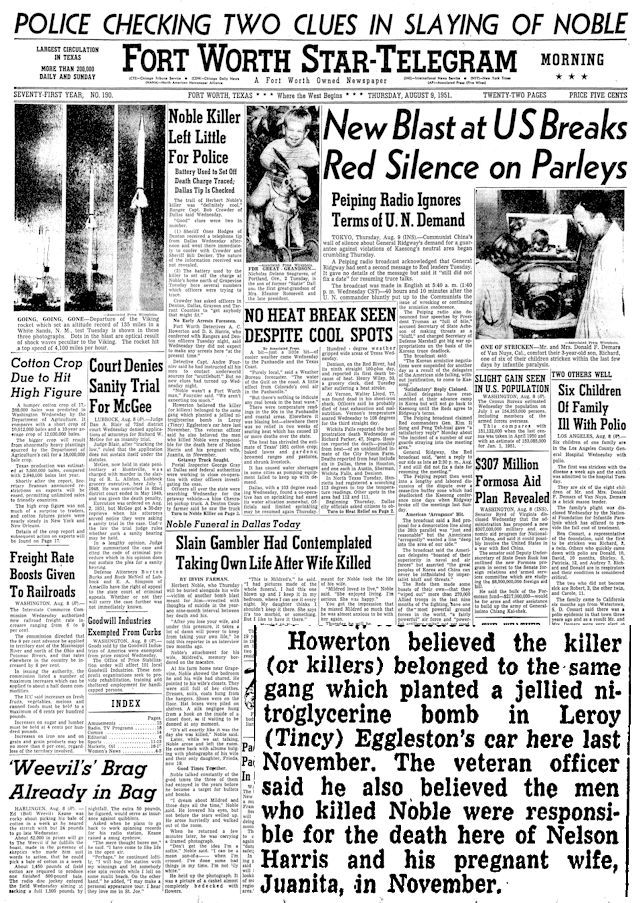

Gambler Herbert Noble had become known as “the Cat” because he had survived eleven attempts on his life. On August 7, 1951 the twelfth attempt was the charm. Dynamite had been planted at the base of the mailbox of his Diamond M Ranch in Denton County. Concealed wires ran from the dynamite through a culvert to a battery and from the battery to a scrub thicket where the killer waited. When Noble stopped his car to get his mail, the killer grounded a wire against a barbed-wire fence.

Gambler Herbert Noble had become known as “the Cat” because he had survived eleven attempts on his life. On August 7, 1951 the twelfth attempt was the charm. Dynamite had been planted at the base of the mailbox of his Diamond M Ranch in Denton County. Concealed wires ran from the dynamite through a culvert to a battery and from the battery to a scrub thicket where the killer waited. When Noble stopped his car to get his mail, the killer grounded a wire against a barbed-wire fence.

Howerton suspected that the killer or killers of Noble also had been behind the Nelson Harris car-bombing and the attempted car-bombing of Tincy Eggleston (see below) just two hours after the Harris bombing.

No one was ever convicted in the Noble murder.

Howerton ranked Jim Thomas, a gunman for hire, as the worst of the local badmen.

Howerton ranked Jim Thomas, a gunman for hire, as the worst of the local badmen.

Thomas was a career criminal, convicted of several crimes and suspected of several more. He was questioned in the car-bomb murders of Herbert Noble’s wife Mildrew and the Harrises and the fatal shootings of gangsters Lon Holley and Que Miller. Thomas was convicted three times for the murders of Dr. and Mrs. Roy Hunt of Littlefield in west Texas and was awaiting a fourth trial when he was killed by a man he had threatened in Oklahoma.

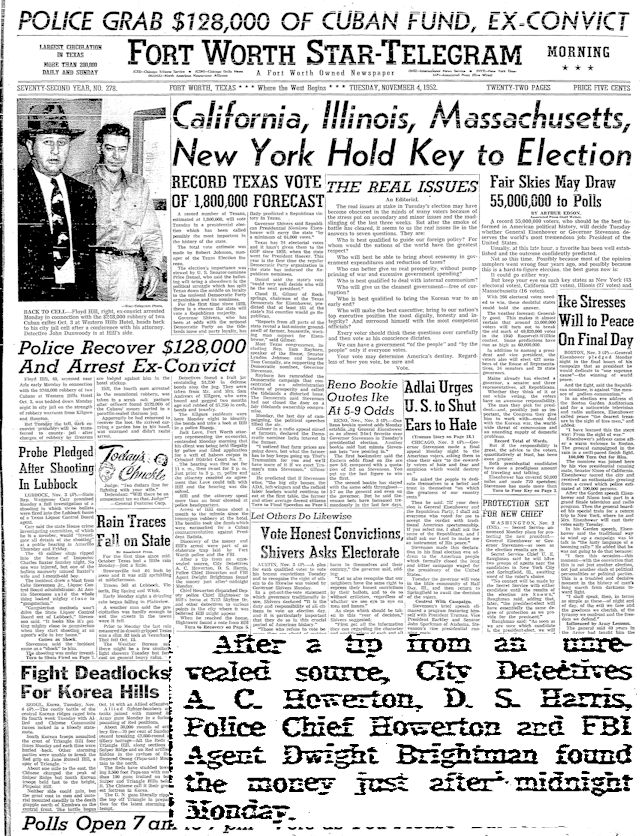

In 1952 three Cubans were in the United States to buy weapons to arm rebels to overthrow Cuban President Fulgencio Batista.

In 1952 three Cubans were in the United States to buy weapons to arm rebels to overthrow Cuban President Fulgencio Batista.

Four men—Sam Brown Cresap, Orville Lindsey Chambless, Floyd Allen Hill, and Gene Paul Norris (see below)—conspired to entice the three Cubans to the Western Hills Hotel, where they robbed the Cubans of $248,000 ($2.2 million today).

Howerton and his brother, Police Chief Roland Howerton, helped recover about half the stolen money.

Of the four conspirators, only Hill served any prison time.

Howerton ranked the Cuban caper as his most memorable robbery.

“I got one of my greatest thrills when I helped dig up a jar containing $128,000 of the money in a field near Azle,” he recalled.

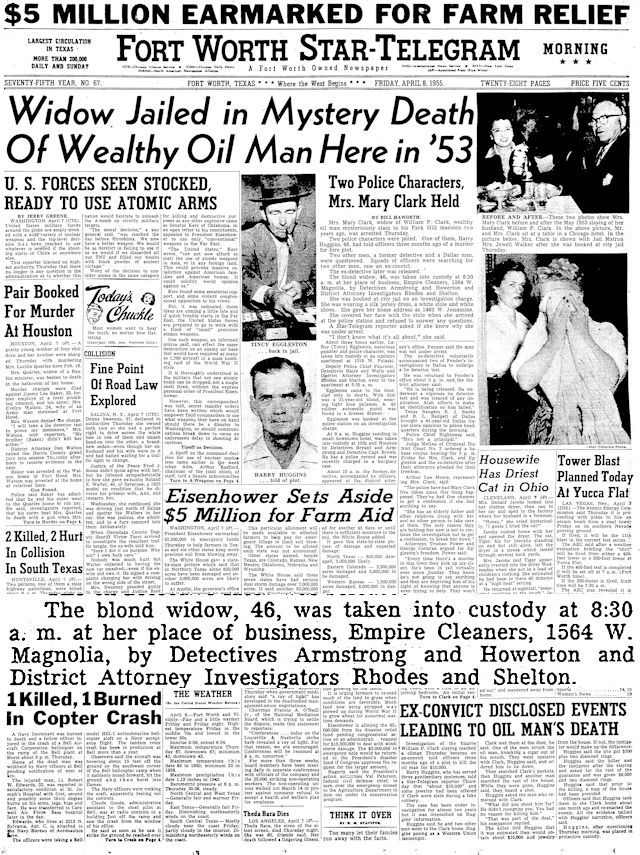

In 1953 wealthy oilman William P. Clark was murdered in his mansion in the fashionable Park Hill addition. Two years later his widow and three gangsters—Tincy Eggleston, Cecil Green, and Harry Huggins—were charged with Clark’s murder. Prosecutors said Mrs. Clark offered the three men money to kill her husband.

In 1953 wealthy oilman William P. Clark was murdered in his mansion in the fashionable Park Hill addition. Two years later his widow and three gangsters—Tincy Eggleston, Cecil Green, and Harry Huggins—were charged with Clark’s murder. Prosecutors said Mrs. Clark offered the three men money to kill her husband.

A. C. Howerton was among the lawmen who arrested Mrs. Clark.

Cecil Green and Tincy Eggleston would never stand trial. Both would be killed gangland style before the end of the year.

Cecil Green and Tincy Eggleston would never stand trial. Both would be killed gangland style before the end of the year.

Of the two remaining suspects, the widow Clark would be acquitted, and Harry Huggins, in return for his cooperation with authorities, was given a “softened” five-year prison sentence.

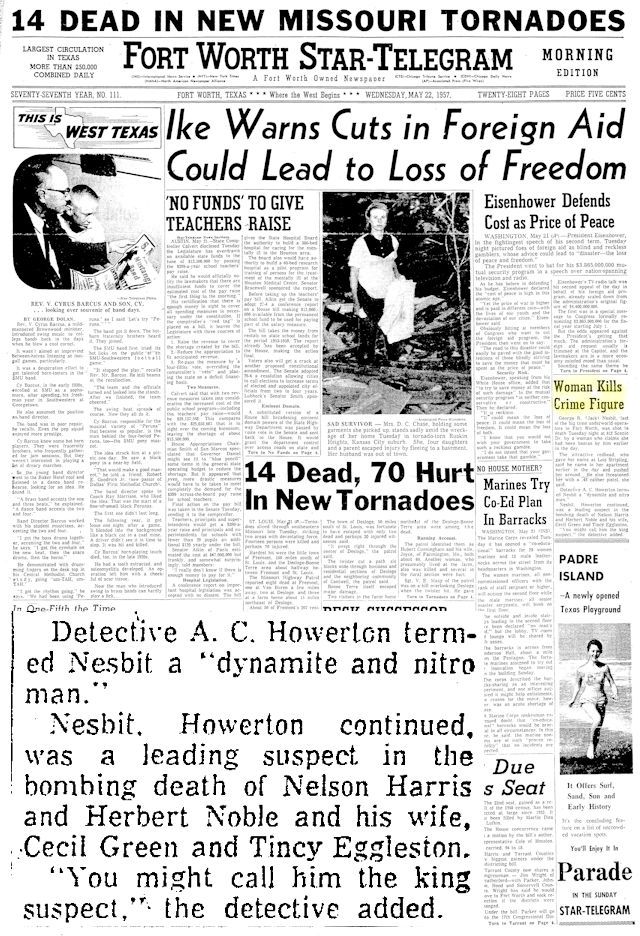

Howerton described Jack Nesbit as a “dynamite and nitro man.” Nesbit had been a suspect in the Mildred Noble and Harris car-bombings, the attempted Eggleston car-bombing, and the bombing of Frank Cates’s gambling house.

Howerton described Jack Nesbit as a “dynamite and nitro man.” Nesbit had been a suspect in the Mildred Noble and Harris car-bombings, the attempted Eggleston car-bombing, and the bombing of Frank Cates’s gambling house.

In 1957 Jack Nesbit was shot to death by girlfriend Lois Stripling after she got tired of being knocked to the floor by him.

Howerton asked the grand jury to no-bill Lois Stripling.

She was no-billed.

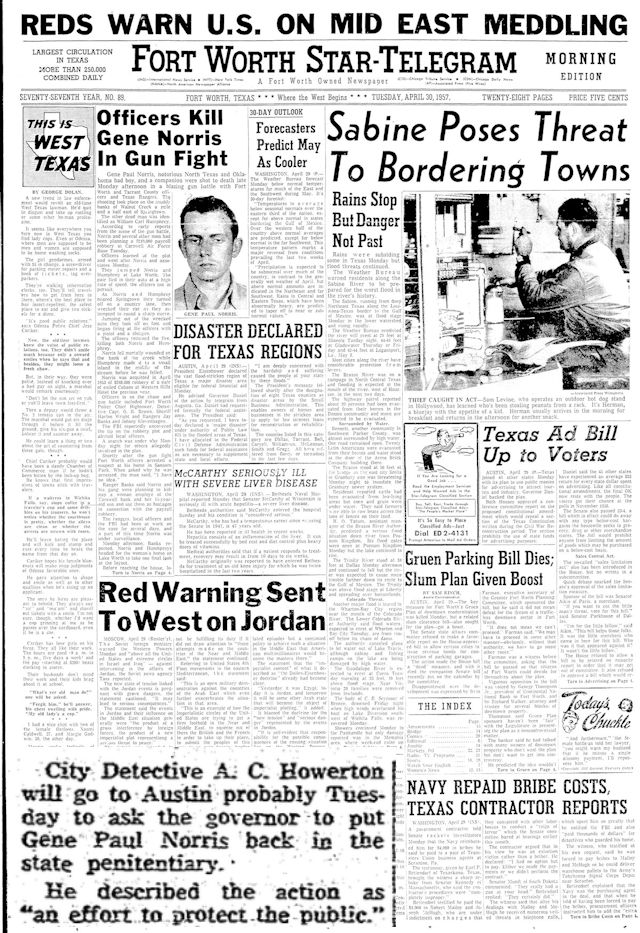

Gene Paul Norris rivaled Jim Thomas as the meanest of a mean lot during Cowtown’s gangland era.

Gene Paul Norris rivaled Jim Thomas as the meanest of a mean lot during Cowtown’s gangland era.

Howerton once personally asked the governor to send Norris back to prison “to protect the public.”

Norris was shot to death by police in 1957 while planning to rob the Carswell Air Force Base branch of Fort Worth National Bank.

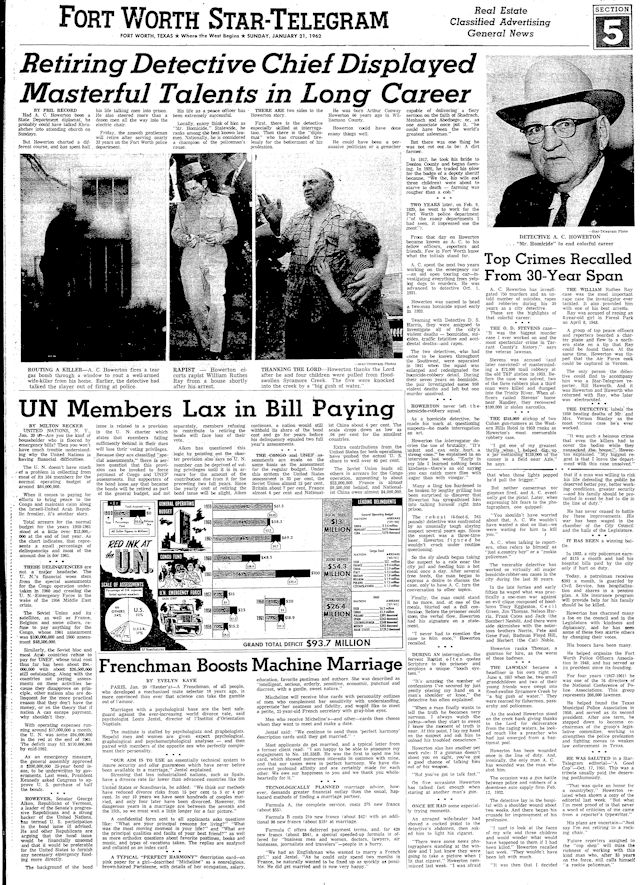

The dean of detectives retired in 1962, still referring to himself as a “rookie policeman.”

The dean of detectives retired in 1962, still referring to himself as a “rookie policeman.”

Elston Brooks recalled that even in retirement Howerton was sought out for his interrogation skill.

In 1963, when President and Mrs. Kennedy spent the night at the Hotel Texas, they had been escorted to and from Carswell Air Force Base by another storied Fort Worth police officer: motorcycle patrolman Lawrence Wood.

When Kennedy was shot in Dallas, amid the pandemonium on the grassy knoll, a woman spectator heard a man shout, “I shot the president!”

The man then jumped into his car and sped off on the turnpike toward Fort Worth. The woman supplied his license plate number to Dallas police. A Fort Worth police car intercepted the suspect on the Fort Worth end of the turnpike and escorted him to the bottom of the South Riverside Drive exit, where he was swarmed by officers.

Wood recalled: “We got him out of the car and then found several boxes of dynamite in the back seat. . . . The man was hysterical. We figured someone might try to kill him, so we ‘ran’ him into a car and into the police station”: Officers surrounded the man, took his arms, and literally ran him every step.

The Secret Service was contacted to confiscate the car and investigate the dynamite.

Wood recalled: “I took him into an interrogation room, but the guy stuttered. And he was so scared, he couldn’t get a single word out, no matter how long he tried.”

Wood called for A. C. Howerton.

“I wanted A. C.,” Wood recalled. “If anybody could do it, I knew A. C. could.”

It took Howerton a while, but he did it.

Wood recalled: “He came out of the room and told me, ‘Lawrence, that’s the best suspect I ever saw. Except for one thing. He didn’t do it.’”

The suspect worked for a dynamite company in west Texas and used empty dynamite boxes as tool chests. He had stopped in Dallas to watch the presidential motorcade, and after the shots were fired he shouted, “They shot the president!”

The woman had thought he shouted, “I shot the president!”

Lee Harvey Oswald was arrested soon after, and the suspect was released.

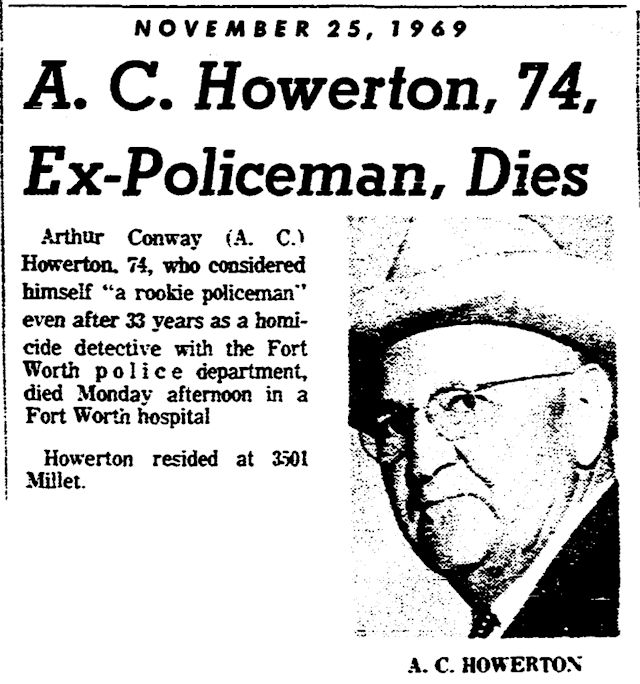

Arthur Conway Howerton died in 1969.

Arthur Conway Howerton died in 1969.

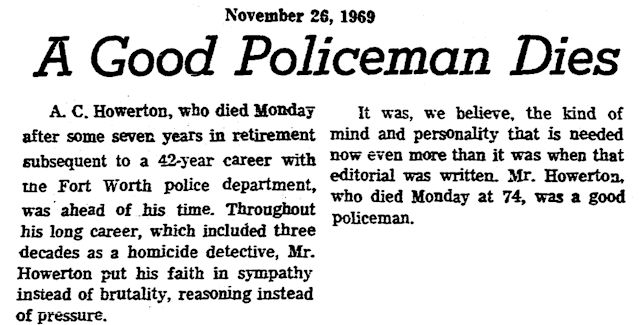

The Star-Telegram praised him as “a good policeman.”

The Star-Telegram praised him as “a good policeman.”

A. C. Howerton is buried in Rose Hill Cemetery.

(Thanks to retired Fort Worth police sergeant and historian Kevin Foster for his help.)

A.C. Was admired and respected by many - from reporters to policemen to governors. He co-founded the Fort Worth Police Association and the Texas Municipal Police Association. He was a presence bigger than life with a laugh to match. I loved him dearly as he was my beloved Grandpa.

AC and Roland Howerton are my great uncles. My grandfather Roy Howerton was a builder. They all three had a great sense of humor as did my great grandfather.

MY GRANDFATHER, DENZIL S HARRIS WAS A.C.’S PARTNER. THEY BOTH RETIRED AT THE SAME TIME.

THEY ARE BOTH BURIED AT ROSE HILL.