Theophilus D. Estes was known around town as simply “Dee.”

In the early twentieth century he had worked for the city waterworks, for the railroads, was active in the Brotherhood of Railway Trainmen.

In the early twentieth century he had worked for the city waterworks, for the railroads, was active in the Brotherhood of Railway Trainmen.

In his spare time he studied law.

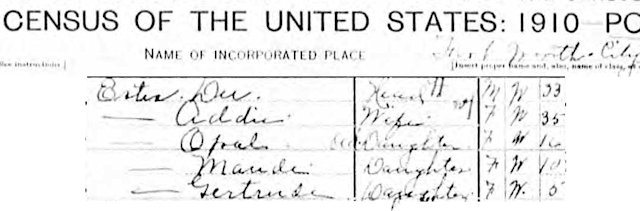

He and wife Addie had three daughters—Opal, Maude, and Gertrude—who in 1910 were sixteen, ten, and five years old.

In 1914 Estes passed the bar exam and began to practice law.

In 1914 Estes passed the bar exam and began to practice law.

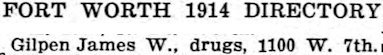

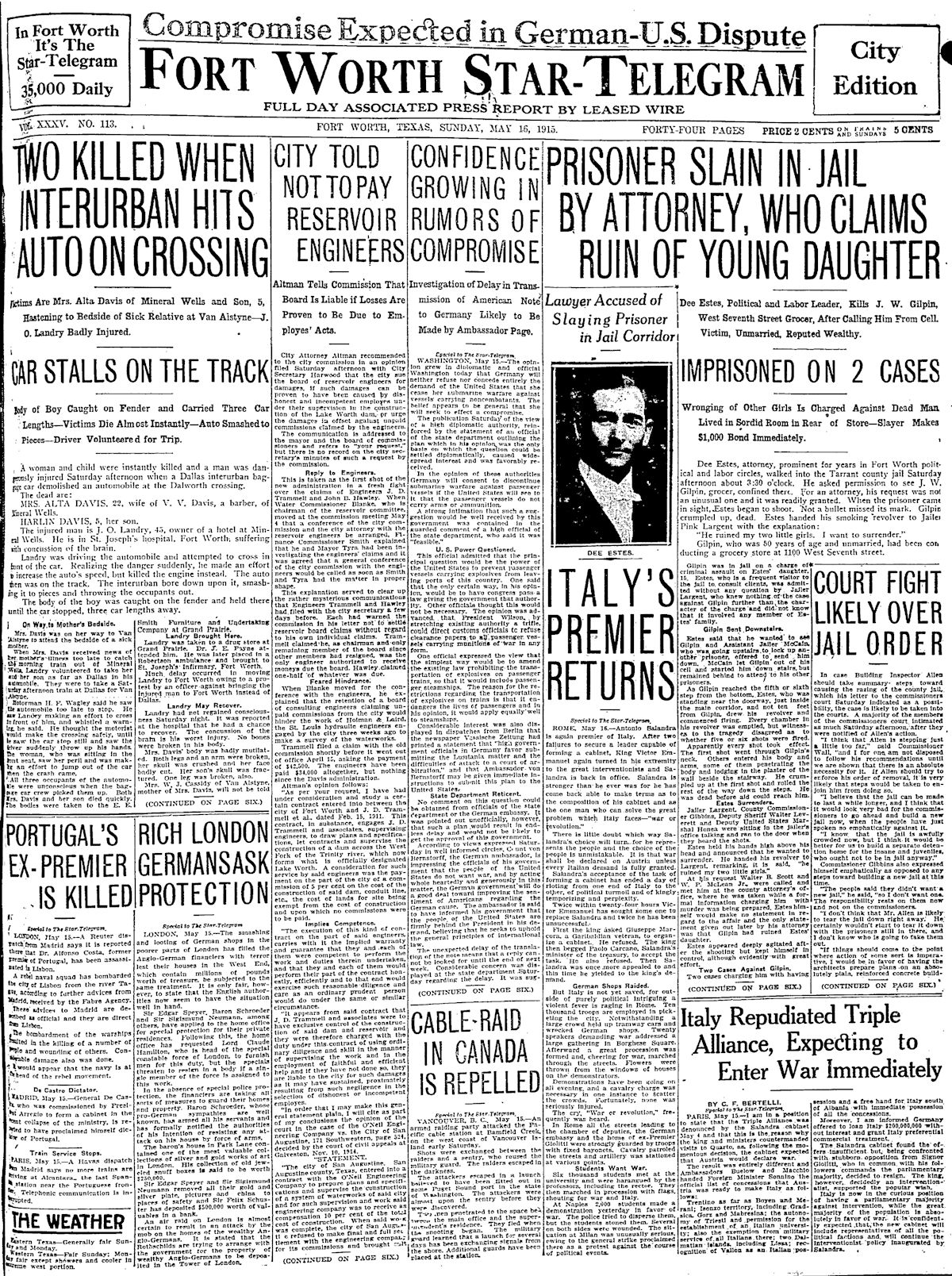

Less is known about James Walter Gilpin. He operated a combination grocery and drug store at 1100 West 7th Street (where the Firestone Apartments are today). He lived in a corner of the stockroom behind the store, was fifty years old, was said to be unmarried but to have a niece and other relatives in McCurtain, Oklahoma.

Less is known about James Walter Gilpin. He operated a combination grocery and drug store at 1100 West 7th Street (where the Firestone Apartments are today). He lived in a corner of the stockroom behind the store, was fifty years old, was said to be unmarried but to have a niece and other relatives in McCurtain, Oklahoma.

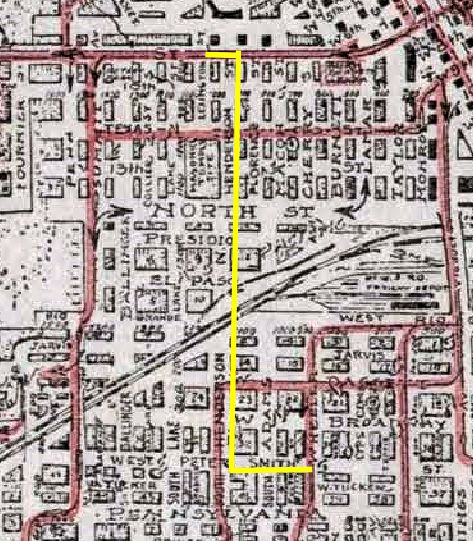

The Estes family lived on Wheeler Street (Fulton Street today) on the near South Side, and Dee Estes’s daughter Maude visited Gilpin’s store often, even though the store was one mile away, and plenty of other stores were closer.

The Estes family lived on Wheeler Street (Fulton Street today) on the near South Side, and Dee Estes’s daughter Maude visited Gilpin’s store often, even though the store was one mile away, and plenty of other stores were closer.

Why?

Because James Walter Gilpin was the Candyman.

Then, in an era when being a victim of sexual assault stigmatized women even more than it does today, teenage girls staged a #MeToo movement. They came forward and told their story:

The Candyman was a sexual predator.

The first girl to come forward gave the second girl courage to come forward. The first two gave courage to others—seven or eight in all, the Star-Telegram later wrote. They all told the county attorney that they had been enticed to Gilpin’s store by the offer of free candy and other merchandise in the store. Gilpin then took each girl to a corner of the stockroom that served as his living quarters and molested her. The Star-Telegram described the living quarters as “sordid in the extreme,” containing just a bunk bed, a water keg, and a shelf. The only light came from a small window.

The second girl to come forward was Dee Estes’s daughter Maude. She had kept silent almost a year. In May 1915 she told the county attorney that when she was fourteen she had been taken to Gilpin’s store by another girl, herself a victim of Gilpin. Maude said Gilpin had molested her.

Maude and Gilpin’s other victims had kept their silence because of enticements, if not threats, by Gilpin and because of the stigma of sexual victimization.

On May 14 Gilpin was arrested in the first case but released on bond. The next day he was arrested in the Maude Estes case and held in jail.

The Candyman seemed to have a foreboding. He told his attorney: “If anything happens to me, wire Rena Gilpin in McCurtain, Oklahoma.”

Gilpin claimed that Rena was his niece.

Meanwhile on May 15 the county attorney’s office telephoned Dee Estes to inform him that his daughter had signed a statement accusing James Walter Gilpin of sexual assault.

When Estes learned of his daughter’s molestation, he made a decision: He was going to kill Gilpin. But Estes faced a choice. As a lawyer, he knew he could wait until Gilpin was free on bond and shoot him in some private setting, perhaps never be apprehended, much less convicted.

But Dee Estes chose to commit his crime in a public place. And not just any public place.

Meanwhile, in the Gilpin case the judge had refused to fix bond, and so Gilpin’s attorneys filed a writ of habeas corpus petitioning the court to fix bond for Gilpin’s release. That writ was on its way to the jail on the afternoon of May 15.

So was Dee Estes.

Sometimes the best credential of all is a familiar face—better than a government-issued ID card, better than a letter of recommendation, better than a passport.

About 40 percent of homicide victims are killed by someone they know—the familiar face of family or friend, customer or colleague.

For example, in Fort Worth history, because their face was familiar to others, the killers of Police and Fire Commissioner Ed Parsley, bank robbers Will Tate and George Terrell, rancher Lemuel Edwards, merchant B. C. Evans, and police officer W. A. Campbell were able to gain access to people and places that a stranger might not.

And so it was on May 15, 1915.

When Dee Estes walked into the county jail building, then located just north of the courthouse, his familiar face was recognized by jailer Pink Largent, who knew Estes to be a frequent visitor to confer with jailed clients. But Largent did not know that Estes’s daughter Maude had made the charge that had put Gilpin in jail for the second time in two days.

Estes told Largent he wanted to see prisoner Gilpin.

Another jailer, J. William McCain, was going upstairs to take a prisoner to his cell and offered to return with prisoner Gilpin. But when McCain reached the cell area, he unlocked the door of Gilpin’s cell and told him to go downstairs unescorted.

As Dee Estes waited on the first floor, he probably assumed that Gilpin would appear in the custody of an armed jailer. There might be collateral damage.

Or worse.

How Estes must have thought the gods of retribution were smiling upon him when he saw Gilpin appear unescorted.

When Gilpin was five or six steps from the bottom of the stairs, Dee Estes stepped forward with a revolver in his hand. From ten feet away he emptied the gun into Gilpin, who collapsed and tumbled the rest of the way down the stairs.

A county jail by its very nature is populated by law enforcement officers. But at the time Dee Estes chose to walk into the jail and commit homicide, also present—in addition to two jailers and Deputy Sheriff Walter Leveritt—were County Commissioner Olin Gibbins and former sheriff and current U.S. Marshal John Honea.

With these men present, Estes handed his smoking gun to jailer Largent, saying that Gilpin had “ruined” his daughter. Estes then raised his hands over his head and said he wanted to be arrested.

He was.

Estes then retained two excellent attorneys: Walter B. Scott and William Pinckney “Wild Bill” McLean Jr., brother of slain County Attorney Jefferson Davis McLean.

Likewise, among those signing the bond for Estes’s release from jail were prominent men: McLean, Brown Harwood (who would become the no. 2 man in the national KKK), C. A. O’Keefe (who would build the Blackstone Hotel), Jesse Lee Johnson (who married Clay Allison’s widow), former sheriff Sterling P. Clark, and County Commissioner Gibbins.

There remain two loose ends to tie up:

- Burial of the dead. James Walter Gilpin, thought to be unmarried by even his attorney, in truth was married to the woman he had said was his niece. Rena Gilpin, mother of Gilpin’s seven children, came down from McCurtain and accompanied his body back to Oklahoma.

- Trial of the killer.

Dee Estes could hardly deny that he killed Gilpin. Too many witnesses. He readily confessed to the killing.

But as a lawyer and a father Estes was familiar with the unwritten law.

According to the Buffalo Law Review, the unwritten law was an uncodified constraint that protected “those who killed to defend the honor of women. . . . a husband, brother, or father could justifiably kill any man who had a sexual relationship outside of marriage with the killer’s wife, daughter, sister, or mother.”

The Review adds: “Criminal defendants who could convince a jury that they killed in defense of the sanctity of their home, and the virtue of their women, were almost certain to be acquitted.” (But the vice was not versa: The unwritten law was less likely to protect a wife who killed her husband’s lover.)

The unwritten law was used as a defense for homicide mostly from the mid-nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth century.

For example, in 1912 during the byzantine Sneed-Boyce feud John Beal Sneed walked into the lobby of Fort Worth’s Metropolitan Hotel and shot to death cattleman A. G. Boyce Sr. as Boyce sat in a chair. Sneed later killed A. G. Boyce Jr. on a sidewalk in Amarillo. Sneed accused father and son of conspiring to take his wife from him. Sneed’s defense at trial was, in part, the unwritten law.

He was acquitted both times.

In 1917 Will Jobe shot and killed Niles City policeman Tom Finch on the sidewalk outside Monnig’s Department Store as passersby watched. Jobe’s defense team showed that his wife had been unfaithful to him with Finch. Jobe was acquitted.

Also in 1917 Reverend C. C. Reneau, jealous of one-legged W. N. Shaw’s attentions to Mrs. Reneau, fired his gun through a bedroom window and killed Shaw as Shaw was alone and buckling on his artificial leg. Reneau pleaded the unwritten law and was no-billed by a grand jury.

Lawyer and aggrieved father Dee Estes clearly was counting on the unwritten law to keep him, too, from the gallows.

It did. In July a grand jury no-billed Estes.

It did. In July a grand jury no-billed Estes.

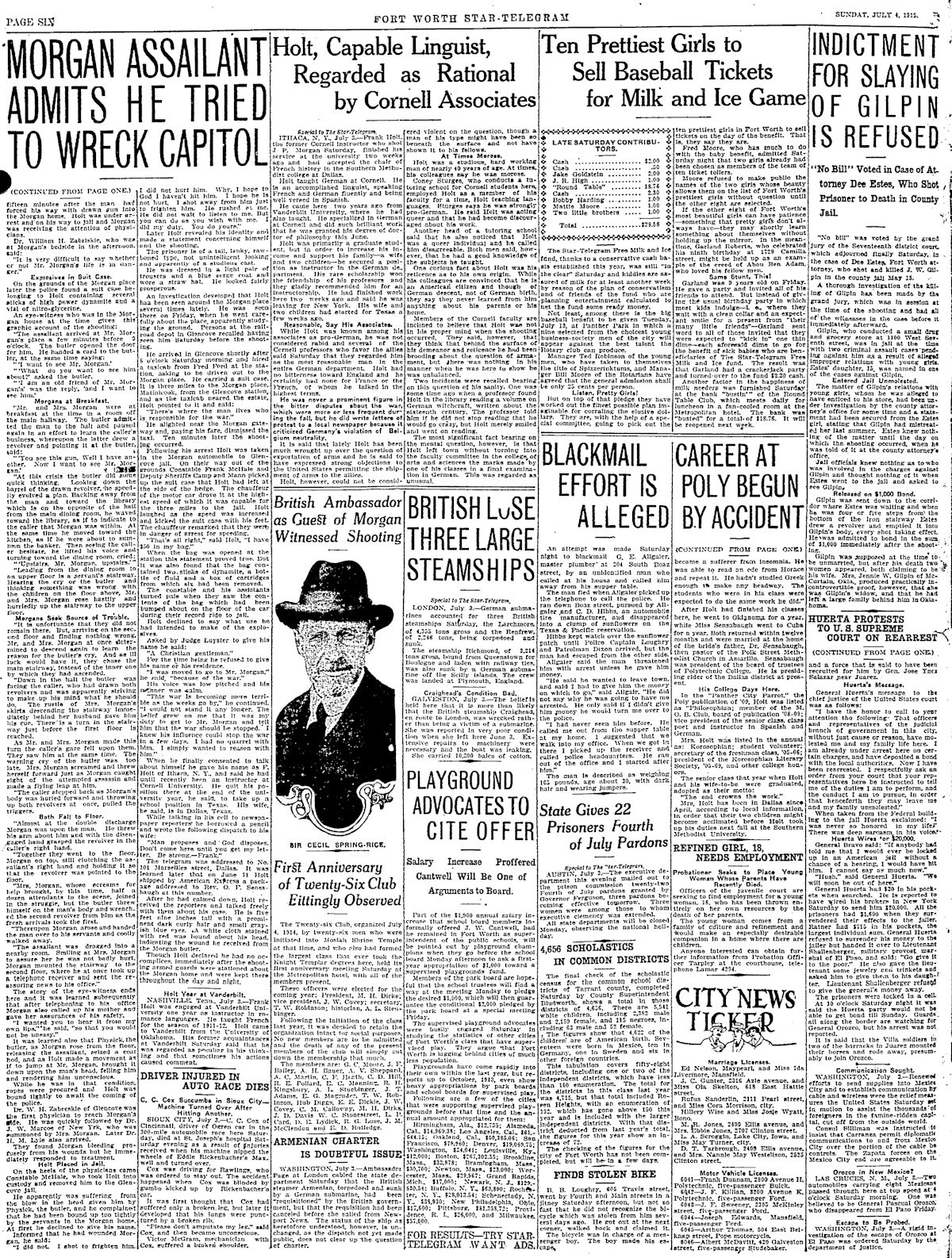

(The rest of that page is devoted to Erich Muenter, aka Frank Holt, a former student and teacher at Polytechnic College who over the Fourth of July weekend had bombed the U.S. Capitol building, shot financier J. P. Morgan Jr., and planted a time bomb on a munitions ship.)

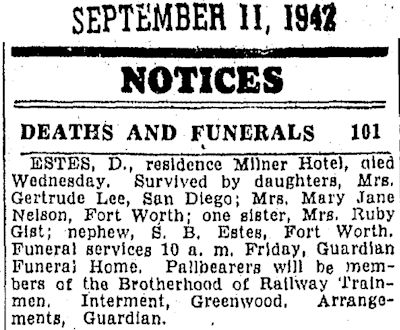

Dee Estes continued to practice law in Fort Worth until his death in 1942.

When Estes died he was living in the Milner Hotel.

When Estes died he was living in the Milner Hotel.

By 1942 the Milner had become a low-rent hotel. Rooms in 1938 were $4 a week ($73 today). But the Milner had once enjoyed far better days: It formerly had been Winfield Scott’s grand Metropolitan Hotel, a favorite of visiting cattlemen and in 1912 the scene of the Boyce-Sneed feud’s first unwritten-law killing.

By 1942 the Milner had become a low-rent hotel. Rooms in 1938 were $4 a week ($73 today). But the Milner had once enjoyed far better days: It formerly had been Winfield Scott’s grand Metropolitan Hotel, a favorite of visiting cattlemen and in 1912 the scene of the Boyce-Sneed feud’s first unwritten-law killing.

(Thanks to retired Fort Worth police sergeant and historian Kevin Foster for the tip.)