Many is the time that Texans—especially farmers and ranchers—have prayed for rain.

In the third week of April 1915 Mother Nature answered those prayers—with a vengeance.

“So y’all would like a heapin’ helpin’ of rain?” she asked sweetly. “That just happens to be our special this week. Would you like lightning and tornadoes with your order? Oh, and how about three days without a hot meal?”

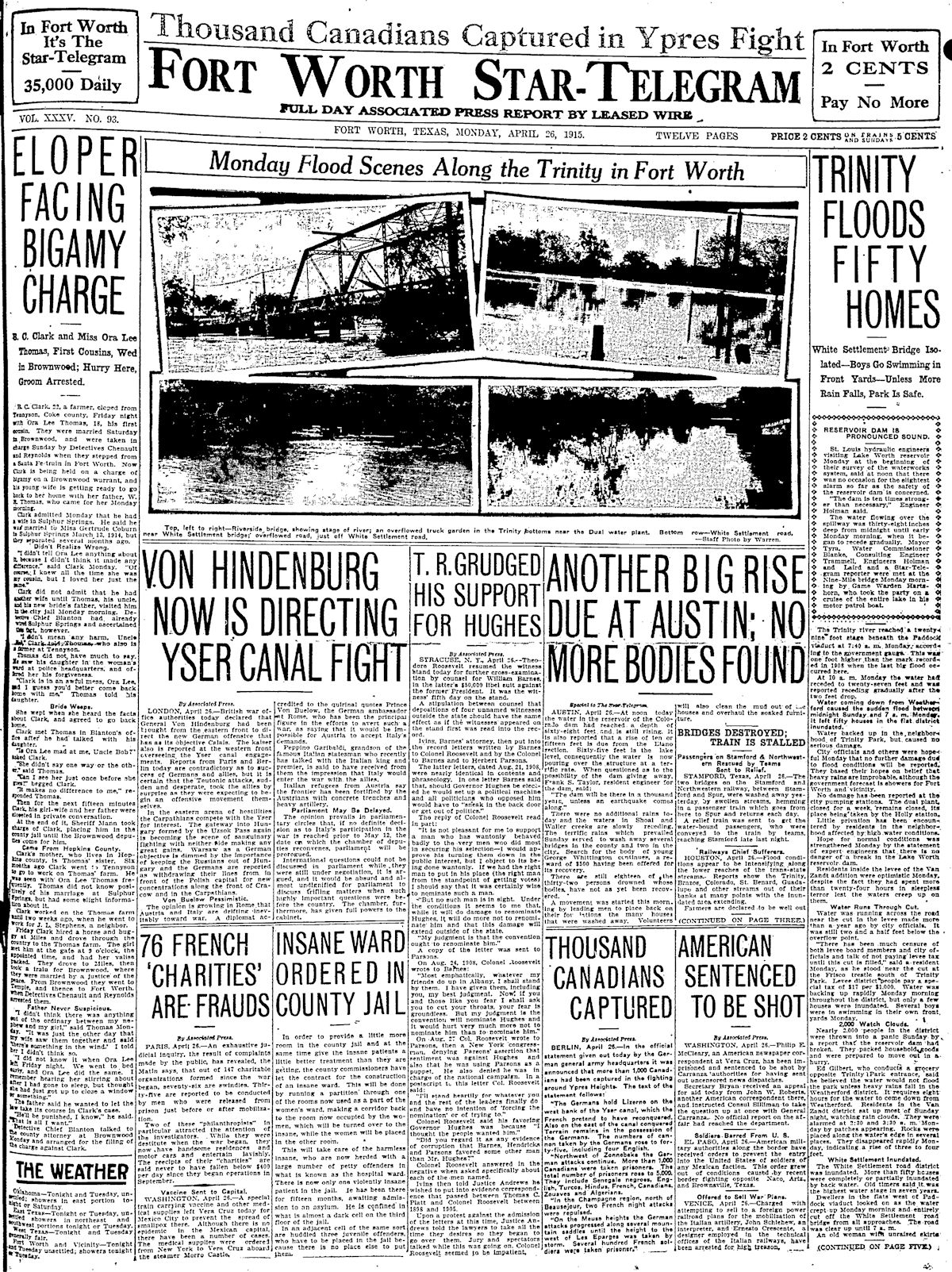

The front pages of newspapers tell the story. Heavy rain was soaking much of Texas.

The front pages of newspapers tell the story. Heavy rain was soaking much of Texas.

Cameron (Milam County) received eight inches of rain overnight April 23. Manor (Travis County) received six inches of rain in one hour. Rivers from the South Canadian to the Guadalupe were out of their banks.

Damage to crops was estimated in the hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Heavy rain washed out railroad tracks and trestles. Trains stopped running. With the railway postal service disrupted, mail had to be delivered by horse and wagon.

Towns were isolated: trains at a standstill, telephone lines down, highways under water.

And then there was the wind: In the Electra oil field (Wichita County) eighty derricks were toppled by high wind. Fifty houses were flattened at Childress.

And the lightning: Lightning struck and destroyed five oil tanks (150,000 gallons) in Thrall (Williamson County) and a warehouse in Dallas.

Worst hit of all was Austin.

Worst hit of all was Austin.

On April 22 about ten inches of rain caused Waller and Shoal creeks in Austin to flash-flood. Entire blocks were swept clean of houses.

In one house eight people drowned.

People and houses were swept downstream for miles.

Because the bodies of some people were never found, the precise death toll in Austin is not known: between thirty and sixty people.

To add irony to injury, an Austin municipal water main burst, leaving a flooded town without water to drink or fight fires.

Two hundred miles north, on April 22 Fort Worth reported a small tornado. Trees, fences, and barns were blown down.

But that was the least of Fort Worth’s problems.

Because also on April 22 the city lost its supply of natural gas.

Lone Star Gas Company received its gas for Fort Worth via a pipeline from the Petrolia gas field in Clay County. Northwest of Fort Worth in the rain-drenched watershed of the West Fork of the Trinity River the pipeline passed through a creek in Wise County that was so flooded that on April 22 the pipeline ruptured, and Fort Worth was left without gas.

In Fort Worth households, no gas meant no hot meals, no hot water for bathing and shaving. Some industries also were hampered by the loss of gas. For example, the printing capacity of the Star-Telegram was limited because natural gas was used as fuel to melt the lead used to cast lines of type and printing plates for the presses. The newspaper had to resort to using gasoline as fuel—a slower process.

Just as Fort Worth was anticipating having natural gas again, Mother Nature dealt a twofer: A second rupture in the pipeline kept bacon and eggs uncooked and chins unshaved in Cowtown one more day.

Just as Fort Worth was anticipating having natural gas again, Mother Nature dealt a twofer: A second rupture in the pipeline kept bacon and eggs uncooked and chins unshaved in Cowtown one more day.

Lone Star sent repair crews from Fort Worth to the site of the rupture on a special train. The men worked in rain and waist-deep water to repair the pipeline.

On April 24 the Star-Telegram reported fourteen dead and eleven missing in Austin.

On April 24 the Star-Telegram reported fourteen dead and eleven missing in Austin.

Lone Star said the gas supply to Fort Worth might be restored that night.

The weather forecast for Fort Worth and vicinity: “Unsettled.”

Uh-oh.

Meanwhile, in Austin on April 25 the death toll was at thirty-two.

Meanwhile, in Austin on April 25 the death toll was at thirty-two.

Then Mother Nature dealt Austin a twofer: Austin suffered a second flood. But this time people were warned, and there was no further loss of life.

In Fort Worth Lone Star now expected the gas supply to be restored on April 25.

Note the headline in the bottom left: “Foot of Water Pouring Over Lake Worth Dam.”

All that rain falling in the West Fork watershed northwest of Fort Worth was rushing downstream.

Good news, bad news: By April 26 Fort Worth had natural gas again. It also had a flood to contend with.

Good news, bad news: By April 26 Fort Worth had natural gas again. It also had a flood to contend with.

Water pouring over the spillway at Lake Worth was now thirty-eight inches deep. Fifty homes in Fort Worth were flooded. Boys were swimming in their front yards.

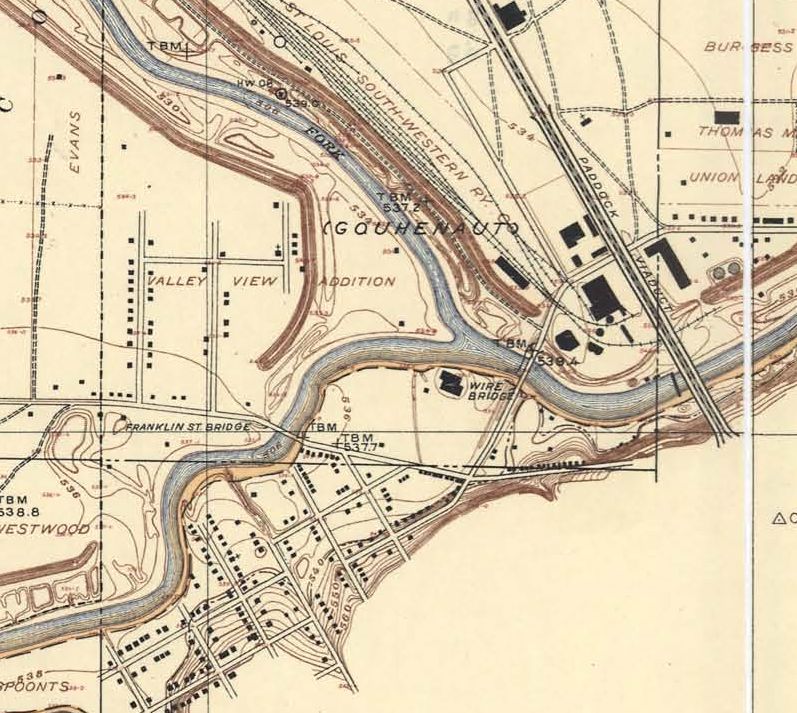

The flood was a stress test of the Lake Worth dam and the levee system. The dam had been completed in 1914. Not yet completed was the eleven-mile levee system along the river to protect the low-lying areas to the west, east, and north of downtown.

On this map of early 1915 the levees are the thick brown lines. You can see gaps between the levees at Franklin Street/White Settlement Road and North Main Street. Because of the bluff, no levees were needed on the south and east sides of the river.

On this map of early 1915 the levees are the thick brown lines. You can see gaps between the levees at Franklin Street/White Settlement Road and North Main Street. Because of the bluff, no levees were needed on the south and east sides of the river.

As the river rose, at the gaps between the levees men, including city jail inmates, built emergency levees using sandbags.

As the level of Lake Worth rose, campers were marooned on islands of high ground and had to be rescued by boat.

Traffic on the Dallas Pike (East Lancaster Avenue) was suspended where Sycamore Creek, was out of its banks. Water on the pike was reported as high as wagon beds.

In the river bottom near Douglas Park water was halfway up the windows of houses in that area.

Residents on the West Side nervously monitored the advance of the flood in their area by placing a rock at the edge of the water. As the water rose and the rock was submerged, they placed another rock at the ever-advancing edge.

Rumors that the dam might fail caused people on the West Side to stay awake at night in readiness to evacuate.

But engineers assured residents that the dam was sound.

On April 27 the water began to recede. People began to return to their homes.

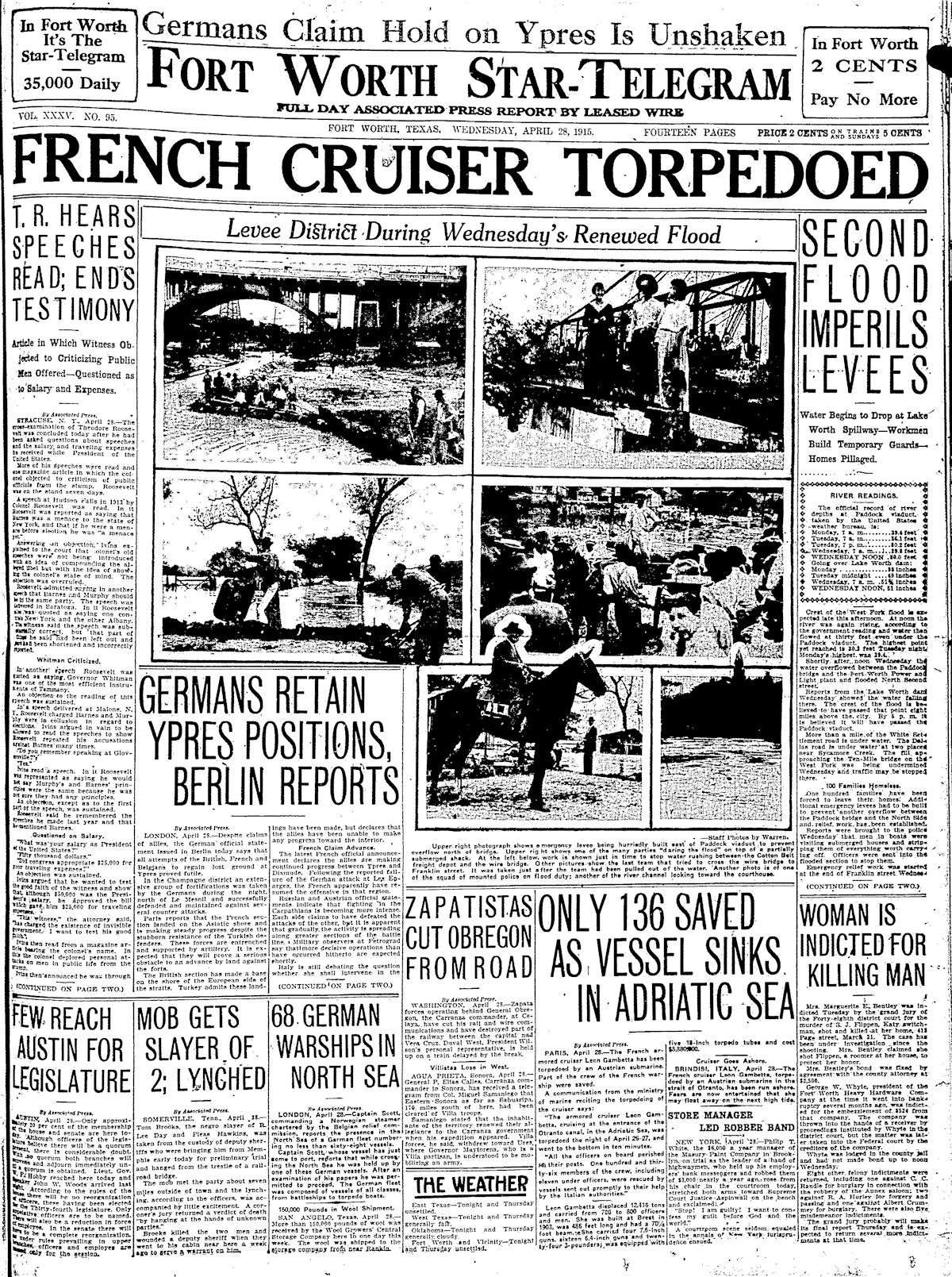

And that’s when Mother Nature dealt another twofer: On April 28 Fort Worth again was flooded, the river rising to the level recorded two days earlier. The water at the weather service gauge at the Paddock viaduct was four feet higher than during the flood of 1908.

And that’s when Mother Nature dealt another twofer: On April 28 Fort Worth again was flooded, the river rising to the level recorded two days earlier. The water at the weather service gauge at the Paddock viaduct was four feet higher than during the flood of 1908.

People gathered on the old wire bridge (1892) near the confluence of the West and Clear forks to watch the river rise. The Star-Telegram reported that a “soda pop vendor” set up a stand and did a “thriving business.”

One hundred people were forced to leave their homes twice in three days.

Numerous thefts from the evacuated homes were reported to police, but none of the robbers was caught. The Fort Worth Relief Association opened a supply station on Franklin Street near the river and furnished food and clothing to victims. The Union Bakery donated one hundred loaves of bread, and the Eagle Steam Bakery donated a wagon load of bread.

As usual, the West Side was flooded, but this time not by the nearby Clear Fork but rather by backwater from the West Fork flowing up the Clear Fork to the West Side from the confluence of the two forks at the viaduct!

Water reached the driving park and houses north of West 7th Street. A mile of White Settlement Road was under water.

Just as with the first flood two days earlier, there again was concern about the Lake Worth dam. Police officers on horseback rode through the river bottom warning people to evacuate. Police telephoned every resident of the lowlands who had a telephone and moved out people who were bedridden and could not leave on their own.

Twenty-five refugees spent the night on the porch of a house on Florence Street downtown.

Other refugees were sheltered at the Van Zandt school on the West Side.

But some people, rather than evacuate their house, huddled on the roof as the water rose, gambling on the water receding before it reached them.

On April 27 the floodwater indeed began to recede. Again. People—for the second time in four days—returned to their homes.

But because of the risk of waterborne disease in the flooded Battercake Flats area in the river bottom below the courthouse, the relief association urged the city to not allow “squatters” to return to the Flats until it had been disinfected.

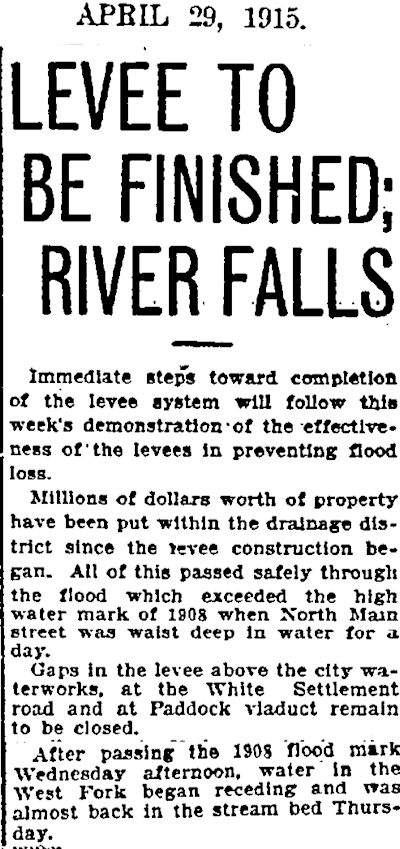

For Fort Worth the silver lining of the flood of 1915 was another twofer:

- The city recorded no fatalities.

- The Lake Worth dam and the levee system (although incomplete) passed the stress test.

The city announced plans to close the gaps in the levee system and reported that parts of town that had flooded in 1908 had not flooded in 1915 even though the high water mark of 1915 surpassed that of 1908.

The city announced plans to close the gaps in the levee system and reported that parts of town that had flooded in 1908 had not flooded in 1915 even though the high water mark of 1915 surpassed that of 1908.

Likewise, the Star-Telegram credited the dam and the levee system with saving lives and property.

Likewise, the Star-Telegram credited the dam and the levee system with saving lives and property.

As the river receded and the skies cleared in April 1915, just as Fort Worth had been flooded seven years earlier in 1908, Fort Worth would be flooded seven years later in 1922.

But, despite the dam and the levees, with deadlier consequences.

Posts about weather:

“Greatest Tragedy of the Century” (Part 1): “Dead Outnumbers the Living”

Winter 1930: Lake Worth Ice Capades

The Deep Freeze of Fifty-One

Texas Toast: The Summers of 1980 and 2011

The Flood of 1889: The First of the Big Four

Double Trouble: The Twofer Flood of 1915

From Beneficial to Torrential: The Flood of Twenty-Two

The Flood of Forty-Nine: People in Trees, Horses on Roofs

Deja Deluge: Forty Years On, the Flood of 1989