It was Fort Worth grown and Fort Worth flown: built at the bomber plant and then taxied next door to fly from Carswell Air Force Base in the Strategic Air Command’s 43rd Bombardment Wing.

The Air Force had begun planning a supersonic bomber during a hot war—Korea. But it took a cold war to turn planning into producing. The Air Force, alarmed at Russia’s advances in long-range bombers, in 1953 awarded a contract to Fort Worth’s Consolidated Vultee (Convair) to build the world’s first supersonic bomber. At that point the plane was not yet officially designated as “B-58,” much less “Hustler.”

The Air Force had begun planning a supersonic bomber during a hot war—Korea. But it took a cold war to turn planning into producing. The Air Force, alarmed at Russia’s advances in long-range bombers, in 1953 awarded a contract to Fort Worth’s Consolidated Vultee (Convair) to build the world’s first supersonic bomber. At that point the plane was not yet officially designated as “B-58,” much less “Hustler.”

By 1955 Convair was hiring engineers (“male or female”) for the big project.

By 1955 Convair was hiring engineers (“male or female”) for the big project.

Sleek, fast, expensive, and radically different, the B-58 was, in automotive terms, Convair’s Corvette—a Corvette with a nine-megaton nuclear bomb in the trunk.

The B-58 was state-of-the-art, with sophisticated avionics and space-age materials (to achieve high strength and low weight, the plane incorporated sections of fiberglass honeycomb sandwiched between aluminum panels and then bonded to the wing’s frame using temperature-resistant adhesives).

The airplane had delta wings instead of swept wings. It had an external fuel/bomb pod instead of an internal bomb bay. Each of the three crew members sat in an escape capsule instead of in an ejection seat. Crew members received automatic voice messages and warnings from a tape system through their flight helmet. (Research showed that a woman’s voice was more likely to get the attention of young men in distracting situations.)

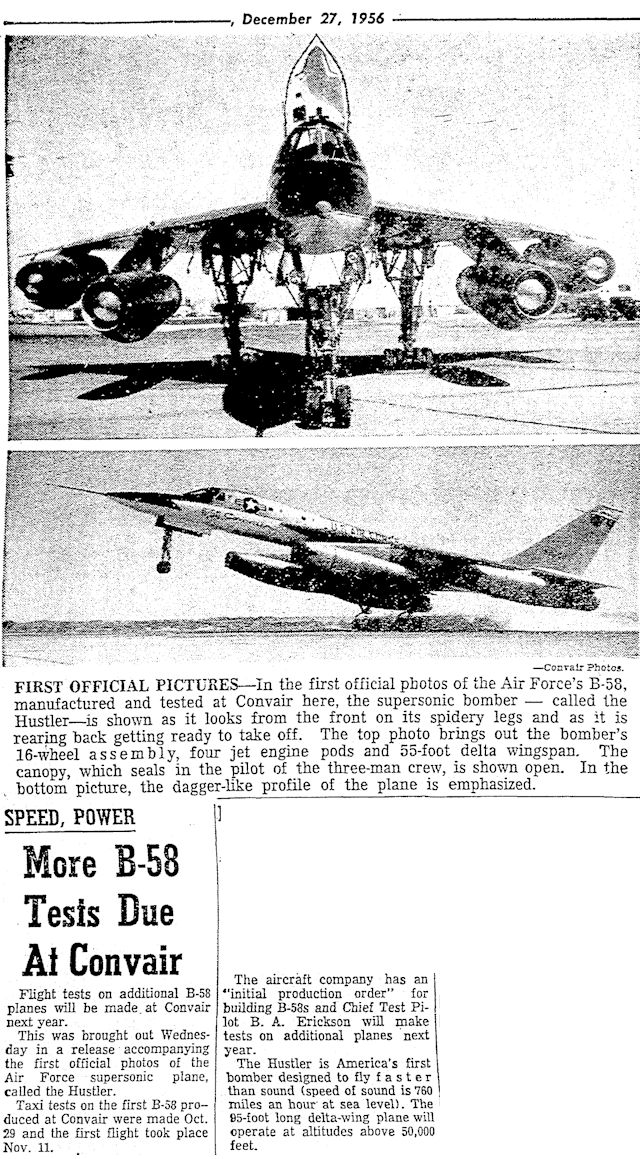

The Air Force released the first official photos of the B-58 when it flew for the first time in 1958. Chief test pilot was Beryl A. (“Just earning shoes for the baby”) Erickson.

The Air Force released the first official photos of the B-58 when it flew for the first time in 1958. Chief test pilot was Beryl A. (“Just earning shoes for the baby”) Erickson.

By 1958 Convair employed twenty-one thousand people to build the B-58. (In 1951 thirty-one thousand had been employed for the B-36.)

By 1958 Convair employed twenty-one thousand people to build the B-58. (In 1951 thirty-one thousand had been employed for the B-36.)

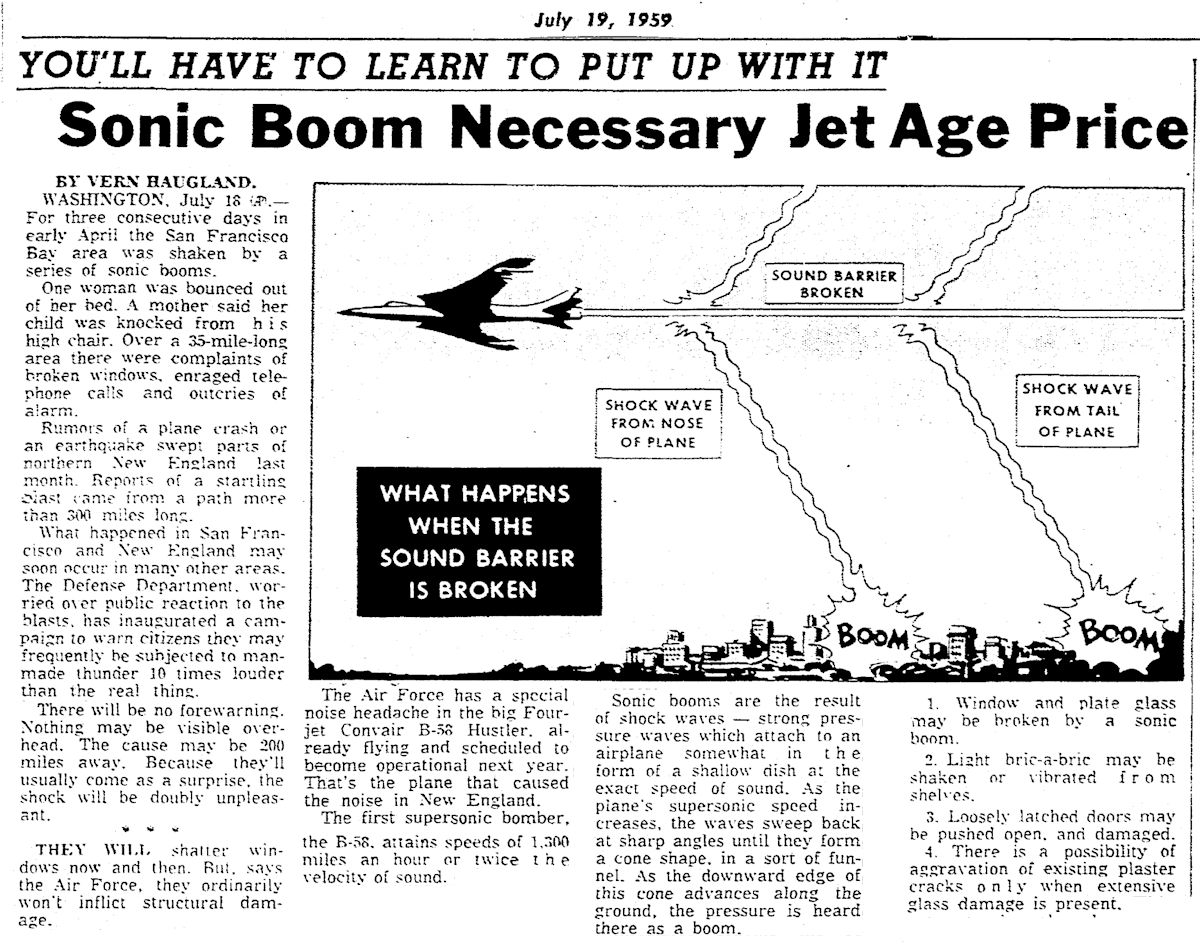

If you lived in north Texas in the 1950s and 1960s you remember the sound of two aircraft. The first sound was subtle: the drone of the six radial engines of a giant B-36 Peacemaker overhead. The second sound was anything but subtle: the sonic boom of a B-58 Hustler.

If you lived in north Texas in the 1950s and 1960s you remember the sound of two aircraft. The first sound was subtle: the drone of the six radial engines of a giant B-36 Peacemaker overhead. The second sound was anything but subtle: the sonic boom of a B-58 Hustler.

Unsettling as the booms were, during the angst of the Cold War, they were the sound of security.

The B-58 was difficult to fly, but its performance was impressive: It could exceed Mach-2 (1,534 miles an hour).

In fact, the B-58 set nineteen world speed records, including coast-to-coast records, and the longest supersonic flight in history.

The B-58 also won the Bleriot, Thompson, Mackay, Bendix, and Harmon air trophies.

“Leaving on a jet plane”: One B-58 pilot who set several speed records was Major Henry John Deutschendorf Sr. In 1961—the year his son John Denver graduated from Arlington Heights High School—Deutschendorf and his crew broke six world speed records (five of them previously held by Russians). (The Jr. in the caption should be Sr. John Denver was Jr.)

“Leaving on a jet plane”: One B-58 pilot who set several speed records was Major Henry John Deutschendorf Sr. In 1961—the year his son John Denver graduated from Arlington Heights High School—Deutschendorf and his crew broke six world speed records (five of them previously held by Russians). (The Jr. in the caption should be Sr. John Denver was Jr.)

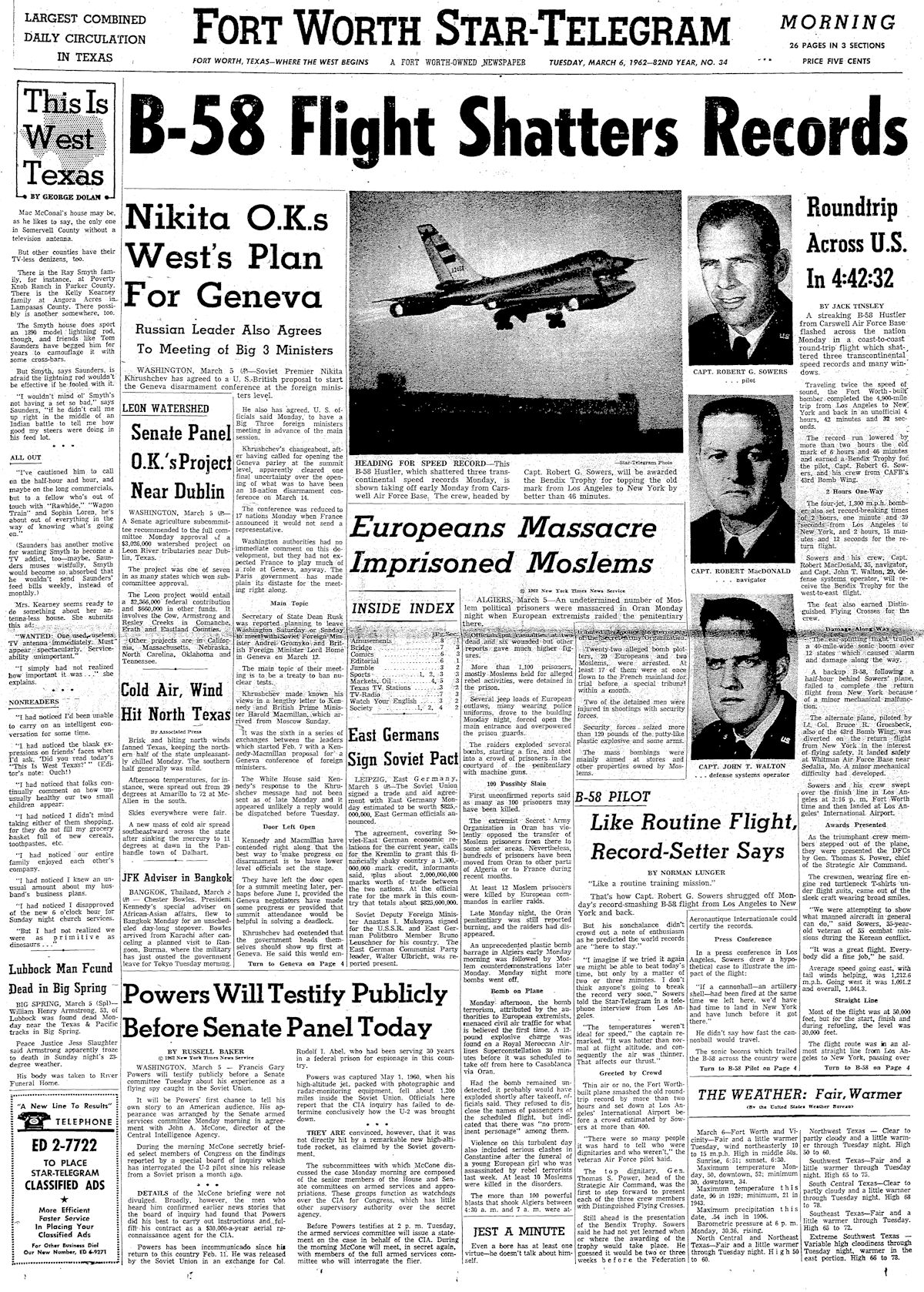

A year later, on March 5, 1962, vest buttons and Champagne corks again were popping at Carswell and the bomber plant after a B-58 named Cowtown Hustler set three transcontinental speed records.

A year later, on March 5, 1962, vest buttons and Champagne corks again were popping at Carswell and the bomber plant after a B-58 named Cowtown Hustler set three transcontinental speed records.

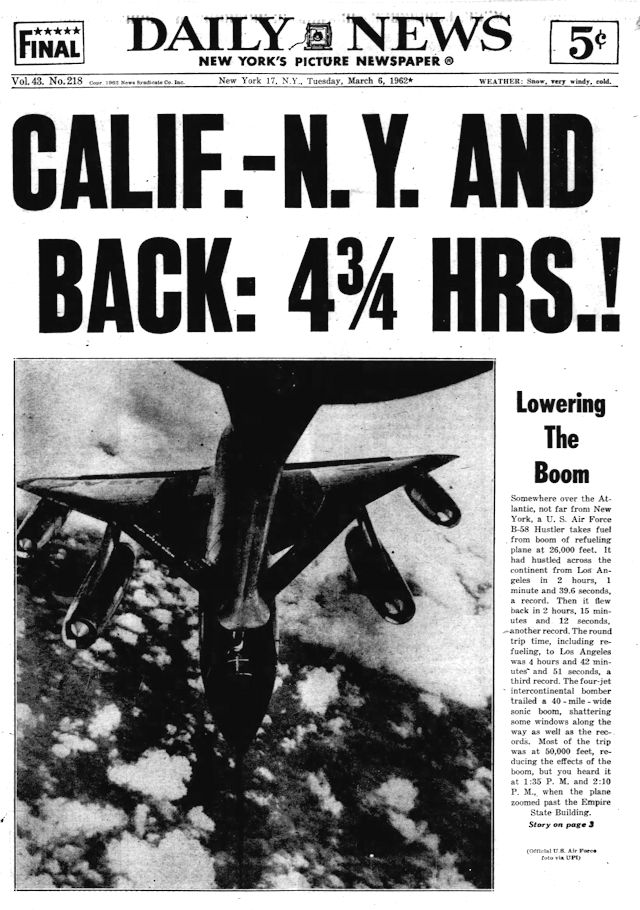

Cowtown Hustler, crewed by pilot Captain Robert Sowers, navigator/bombardier Captain Robert Macdonald, and defense system operator Captain John Walton, set a transcontinental speed record by flying nonstop from Los Angeles to New York and back in 4 hours, 42 minutes. The previous round-trip record was broken by more than two hours.

The first leg (Los Angeles to New York) was completed in 2 hours, one minute at an average speed of 1,214 mph. The return flight was completed in 2 hours, 15 minutes at an average speed of 1,081 mph.

The mission was named “Operation Heat Rise.”

Captain Walton later explained: “The name was ‘Operation Heat Rise’ because we were pushing the ram air temp above the normal operating limit approaching the point where the aircraft tended to melt.”

Yikes.

Cowtown Hustler raced across country against another B-58 of the 43rd Bombardment Wing. Cowtown Hustler’s call sign was “Tall Man Five Five.” The second B-58 was “Tall Man Five Six.”

Captain Walton later said: “We crossed the finish line at New York in 2 hours, 58.71 seconds. We really wanted to break the two-hour LA-to-New York barrier, but it was not to be. We did beat Tall Man Five Six—by all of one minute.”

A mechanical problem forced Tall Man Five Six out of the race on the return flight.

Captain Walton later explained why the return flight was especially remarkable: “The B-58 could fly faster than the rotational speed of the Earth [1,040 mph]. We actually beat the sun by about three-quarters of an hour in the New York-to-Los Angeles race.”

Pilot Sowers said of Operation Heat Rise: “Like a routine training mission.” Sowers knew his way around a cockpit: He had flown thirty-five combat missions in the Korean War.

Cowtown Hustler completed the round trip in Los Angeles at 3:16 p.m. Fort Worth time. Along the way its sonic booms broke windows and plate glass, cracked plaster, set dogs to barking, and startled people across the country, especially when it flew lower than 50,000 feet—during the start and finish in Los Angeles, during turnaround in New York, and during aerial refueling over Kansas. (For aerial refueling the airplane descended to 30,000 feet and slowed to a pokey 540 mph.)

Cowtown Hustler completed the round trip in Los Angeles at 3:16 p.m. Fort Worth time. Along the way its sonic booms broke windows and plate glass, cracked plaster, set dogs to barking, and startled people across the country, especially when it flew lower than 50,000 feet—during the start and finish in Los Angeles, during turnaround in New York, and during aerial refueling over Kansas. (For aerial refueling the airplane descended to 30,000 feet and slowed to a pokey 540 mph.)

Emergency switchboards were flooded with frantic telephone calls about “explosions.”

Captain Walton later said of Cowtown Hustler: “The aircraft was a standard production version with no special modifications of any kind. The ground crew waxed and polished the aircraft until it shined, but other than that it was flown like any other mission.”

After the Cowtown Hustler landed at Los Angeles, General Thomas S. Power, chief of SAC, awarded the three crew members the Distinguished Flying Cross for their achievement.

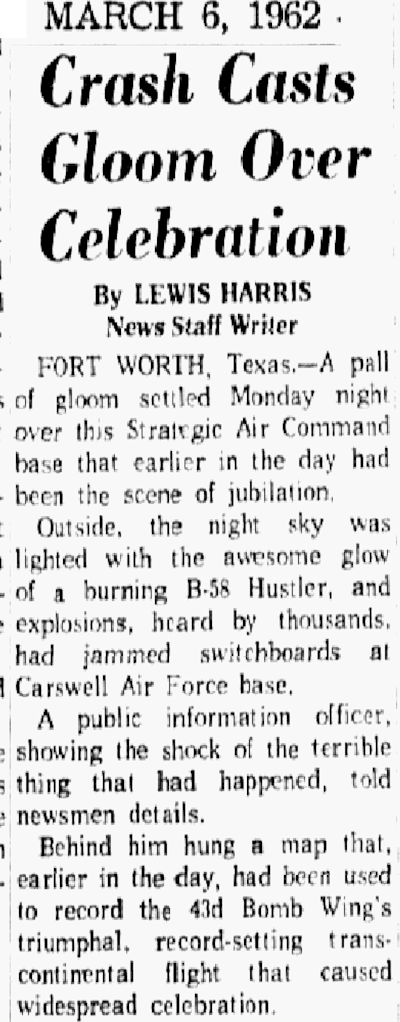

But at 9:30 p.m. on March 5, 1962, six hours after the Cowtown Hustler crossed the finish line in Los Angeles, as bubbles were still rising in Champagne glasses at Carswell, a boom shook the ground and rattled windows at the base.

But this boom was not caused by a B-58 breaking the sound barrier.

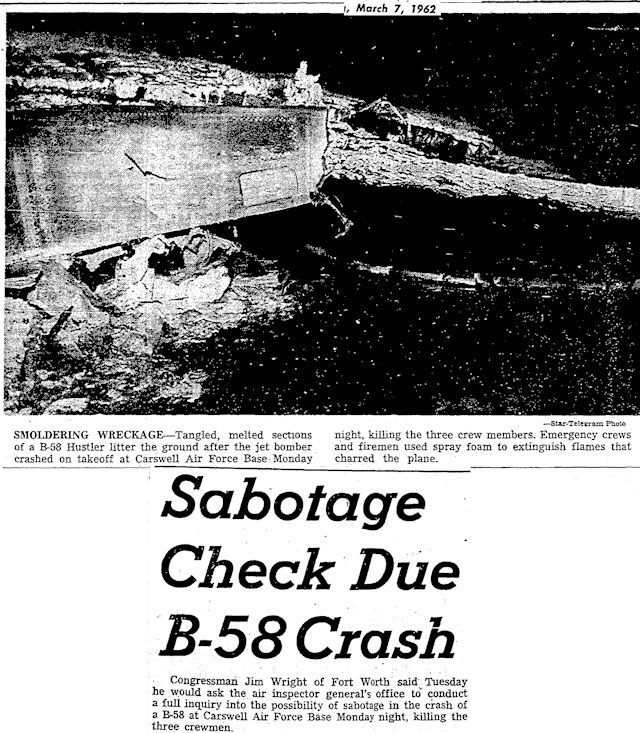

A B-58 of the 43rd Bombardment Wing—sister ship of the Cowtown Hustler—had taken off on a night training mission. At the end of the runway the plane veered to the right, ripped through a chain-link fence, tore apart, and crashed about seventy-five yards short of Lake Worth.

A B-58 of the 43rd Bombardment Wing—sister ship of the Cowtown Hustler—had taken off on a night training mission. At the end of the runway the plane veered to the right, ripped through a chain-link fence, tore apart, and crashed about seventy-five yards short of Lake Worth.

Residents of the Carswell area heard an explosion followed by two more. They saw an orange fireball in the sky. Flames two hundred feet high were visible for miles. Metal debris was scattered over a radius of 250 yards.

One airman said, “It seemed like the whole flight line was on fire. It was just a big spreading stream of fire.”

All three crew members were killed: pilot Captain Robert Harter, navigator/bombardier Captain Jack Jones, and defense system operator First Lieutenant James McKenzie. McKenzie had managed to eject from the plane, but his escape capsule landed in the flaming wreckage.

All three crew members were killed: pilot Captain Robert Harter, navigator/bombardier Captain Jack Jones, and defense system operator First Lieutenant James McKenzie. McKenzie had managed to eject from the plane, but his escape capsule landed in the flaming wreckage.

The plane crashed into one of the base’s ammunition dumps. The plane was not carrying a nuclear bomb, and ammunition in the dump was not detonated.

Other B-58s parked nearby were moved away from the flaming wreckage. A base spokesman said those planes were “loaded.”

Congressman Jim Wright called for an investigation into possible sabotage in the crash, but the cause was ruled to be mechanical failure of the flight control system due to hydraulic system failure on takeoff.

Congressman Jim Wright called for an investigation into possible sabotage in the crash, but the cause was ruled to be mechanical failure of the flight control system due to hydraulic system failure on takeoff.

Ultimately the B-58, like all warplanes, became outdated. It was expensive to build ($80 million each in today’s dollars) and to maintain (the average maintenance cost per flying hour for the B-47 was $361, for the B-52 $1,025, and for the B-58 $1,440). It also was prone to accidents (twenty-six B-58s were lost in accidents: 22 percent of the total production).

The B-58 Hustler, the fastest—and loudest—thing in the sky, was retired in 1970, replaced by the F-111 (also built at the bomber plant).

The record-breaking Cowtown Hustler is on display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio. (Photo from U.S. Air Force.)

The record-breaking Cowtown Hustler is on display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio. (Photo from U.S. Air Force.)

Watch a 1962 documentary narrated by Jimmy Stewart:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IYvsjGroa78

I was with the B-58’s 43rd A&E at Carswell starting in July 1961 through to leaving the program in December 1965 at Little Rock AFB. As a young airman working with the engineers from CONVAIR, Motorola, Hoffmann, and Bendix Pacific I can only say that the experience pushed myself and several others to continue with education and make the Air Force a Career. I can only say that my time with the program were the best days of my 21 year career. I also remember the crash which was the saddest day of my time at Carswell.

I grew up across the lake from the bomber plant and Carswell. I well remember those sonic booms.

Kids today would think we make up stuff like “sonic booms.”

Carol I did too, in White Settlement. On Sandell just down from Brewer. Moved away in 1960, but my childhood home.. the dinnertime BOOMS!