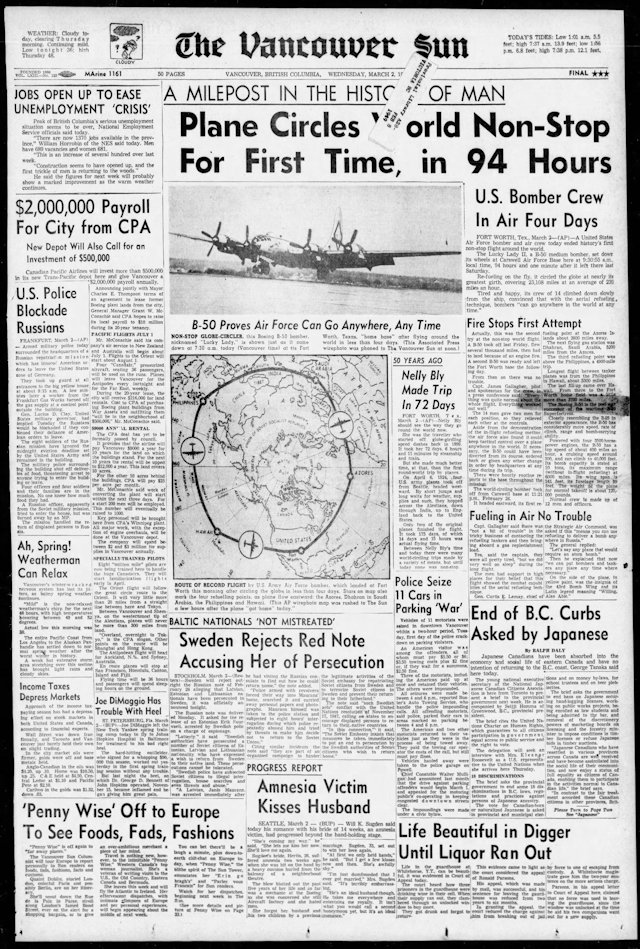

It was a top-secret mission of the U.S. Air Force. So secret that spouses of the fourteen crew members of the B-50 Superfortress Lucky Lady II were not told the true nature of the mission. Foreign governments also were kept in the dark even as the bomber crossed their air space on what the Air Force insisted was a routine “training mission.” The Star-Telegram later reported that the plane’s identification numbers were changed four times during the flight “to prevent the real nature of the mission from becoming known.”

Newspapers and radio stations were especially kept in the dark. Star-Telegram publisher and Fort Worth head cheerleader Amon Carter, with his connections that reached to the Pentagon and the White House itself, may have known in advance about the flight. If he did know, how he must have chafed at being sworn to secrecy.

On March 2, 1949 reporters from around the country were summoned to Carswell Air Force Base, told only that “something big—one of the biggest things that has ever happened in aviation history—was about to break.”

That “something big” was revealed only after Lucky Lady II had passed El Paso, five hundred miles away from Carswell. But for Lucky Lady II five hundred miles away was practically back home again compared with where the plane had been:

around the world.

Nonstop.

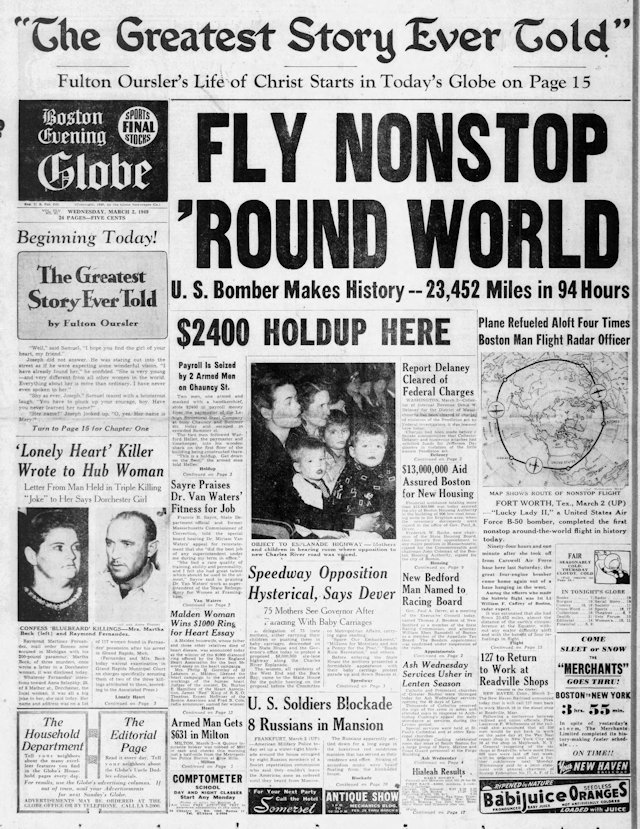

That’s 23,452 miles without rubber touching runway.

General Curtis LeMay, head of the Strategic Air Command, had assigned a pool of five B-50s to attempt the record-breaking flight: a primary bomber and four alternates. The primary bomber, Global Queen, had taken off on February 25 to circle the globe but was forced to land in the Azores because of an engine fire.

That’s how Lucky Lady II got promoted.

Crew members were given three hours’ notice that they would be attempting the unprecedented flight.

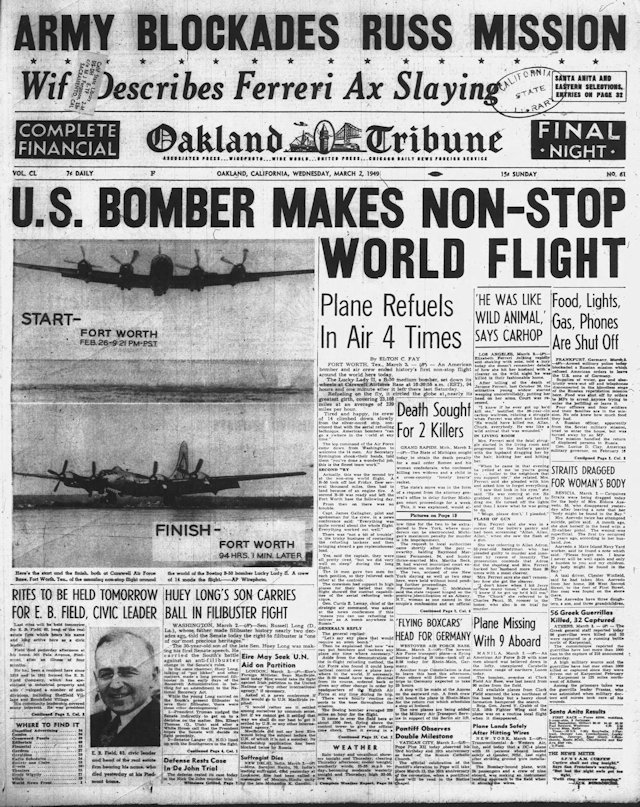

On February 26 the bomber took off from Carswell, passing the control tower at 12:21 p.m., and headed east toward the Atlantic Ocean.

Ninety-four hours and one minute later, at 10:22 a.m. March 2, the bomber again passed the control tower at Carswell, marking the end of its around-the-world flight.

Amon Carter’s Star-Telegram got the words “Fort Worth” in the banner headline not once but twice. On this day Fort Worth—already “where the West begins”—was where the world began and ended.

The cameras and typewriters of the Star-Telegram clicked and clacked a symphony, with photos and sidebar stories on pages 2, 3, 11, and 24.

The cameras and typewriters of the Star-Telegram clicked and clacked a symphony, with photos and sidebar stories on pages 2, 3, 11, and 24.

The B-50 was a post-World War II revision of the B-29 with larger engines. It was the last piston-engine bomber Boeing built for the Air Force. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

The B-50 was a post-World War II revision of the B-29 with larger engines. It was the last piston-engine bomber Boeing built for the Air Force. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

Wingspan: 141 feet

Fuselage length: 99 feet

Maximum range without refueling: 6,000 miles

Top speed: 400 miles per hour

Cruising speed: 300 miles per hour

Top altitude: 40,000 feet

Upon landing the crew members of Lucky Lady II showed no apparent physical exhaustion. They were clean shaven, if a bit wobbly on land legs as they answered questions from the media.

Lucky Lady II commander Captain James Gallagher, twenty-eight, said the flight went without a hitch.

During the flight the bomber was in constant communication with Carswell and Strategic Air Command headquarters at Omaha. The in-air refuelings were well executed, with the bomber never leaving its charted course or slowing its speed. The aircraft was refueled four times by modified B-29s over the Azores, Saudi Arabia, Clark Air Base in the Philippines, and Hickam Air Force Base in Hawaii, proving that the Air Force could carry ten-ton bomb loads for days without interruption.

The bomber returned to Carswell two minutes ahead of the ETA that had been calculated when the plane took off from Carswell. One of the flight’s pilots said he gained four pounds “sitting in the driver’s seat with nothing to do—easy living.”

The bomber flew at altitudes between 10,000 to 20,000 feet and completed the trip at an average speed of 249 mph.

Crew members were greeted at Carswell by Air Secretary Stuart Symington and General LeMay.

General LeMay, asked if the flight showed that U.S. bombers could take off from the United States to drop nuclear bombs on Russia, said, “Let us say we can deliver an atom bomb to any place in the world that requires one.”

Symington called the flight “an epochal step in the development of air power. This flight turns medium-type bombers into intercontinental bombers.”

The Air Force declared the flight a success in terms of not only aviation but also security.

General LeMay said, “This operation . . . was a test of security—to see if such a mission could be accomplished without the knowledge of such gentlemen as yourselves, columnists and newspapermen. Though hundreds of people were involved all around the world, dozens of radio stations, not a single one knew what was going on. The plane’s numbers were changed at every clearance, and no inkling of what it was doing leaked out to any ground station personnel on the entire route.”

The flight was news across the country, putting the Fort Worth dateline on front pages from Oakland to Boston.

The flight was news across the country, putting the Fort Worth dateline on front pages from Oakland to Boston.

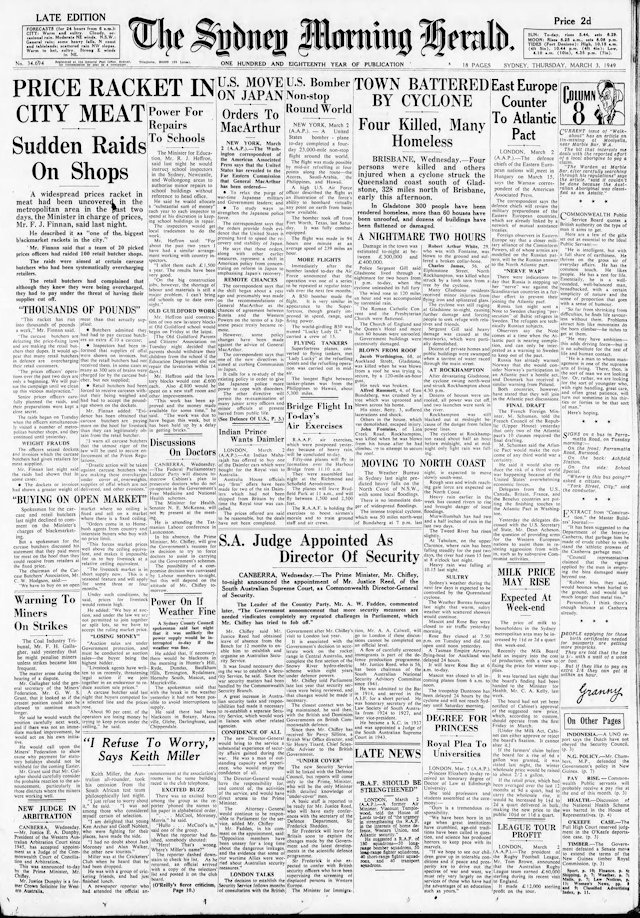

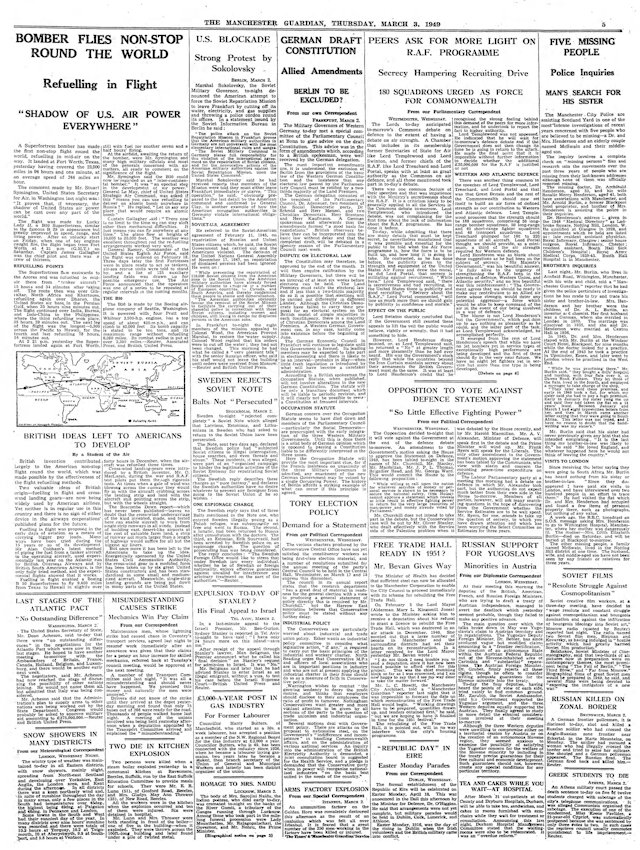

The flight was big news in other English-speaking countries.

The flight was big news in other English-speaking countries.

Even in Dallas.

Even in Dallas.

For their record-breaking flight the crew members of Lucky Lady II were awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

The next year Lucky Lady II landed in the desert when its engines failed on a maintenance test flight. The aircraft was badly damaged and retired from the Air Force. Only the fuselage was preserved. It is on display at Planes of Fame Museum in Chino, California, a reminder of the day when the world began and ended in Fort Worth.

The next year Lucky Lady II landed in the desert when its engines failed on a maintenance test flight. The aircraft was badly damaged and retired from the Air Force. Only the fuselage was preserved. It is on display at Planes of Fame Museum in Chino, California, a reminder of the day when the world began and ended in Fort Worth.

British newsreel footage:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OXf1fSiOYPs