She moved from a cloistered world of nuns to a world of battle-scarred soldiers, reckless wildcatters, and even prize fighters and then on to a white-collar world dominated by still more men, responding to each admonition of “But a woman can’t do that” with a “This woman can” determination.

Matilda Catharine Oglesby was born in Missouri in 1895. She and her family soon moved to Denison, where her father managed a hotel.

When she was a girl, Oglesby recalled years later, young women were taught to “read, write, and embroider.”

She said, “We were trained to be ladies. My mother didn’t approve of women being educated.”

Nonetheless, Oglesby was educated: at St. Joseph’s Academy, an all-girls Catholic school in New York state. Upon graduation in 1914 she studied music, dance, art, voice, and drama in Chicago and New York City.

She returned to Texas but re-entered the world of nuns, teaching at Fort Worth’s Our Lady of Victory academy. Both academies had been founded by the Sisters of St. Mary of Namur.

Oglesby taught English and expression at OLV and also was a private tutor of expression and a director of plays.

Oglesby taught English and expression at OLV and also was a private tutor of expression and a director of plays.

Then, in 1917, at age twenty-two, she traded the classroom for the newsroom: She worked briefly as a reporter for the Fort Worth Record and then was hired by the Star-Telegram as its first woman reporter. Years later she recalled that when she interviewed for one of her first newspaper jobs—probably at the Star-Telegram—she presented the editor with seven reasons why he should hire her. She said he later admitted that he had hired her just to get her out of his office, intending to have someone else fire her.

But that editor soon learned that Catharine Oglesby was not pink slip material.

With her background in music and drama, at first she was assigned to review concerts and the theater.

With her background in music and drama, at first she was assigned to review concerts and the theater.

But Catharine Oglesby had begun her journalism career when Fort Worth stood at the intersection of a world war and an oil boom:

In April 1917 America had declared war on Germany. Fort Worth was chosen as the site of two Army camps: Camp Bowie and Camp Taliaferro, which consisted of three airfields to train pilots.

Meanwhile, eighty miles to the west, in October William Knox Gordon had discovered oil on the farm of John Hill McCleskey, creating a frenzy of buying, selling, drilling, building.

By late 1917 young men were training for war at four local military bases, and in the Ranger oil fields hardscrabble farmers were becoming millionaires overnight.

Those two environments were rife with human interest stories.

Catharine Oglesby would write hundreds of them during her brief career at the Star-Telegram.

Oglesby had used her refined education to write about concerts and the theater. Now assigned to cover the men of the military bases, she used her small-town upbringing to write features about the soldiers and pilots training for—and returning from—war.

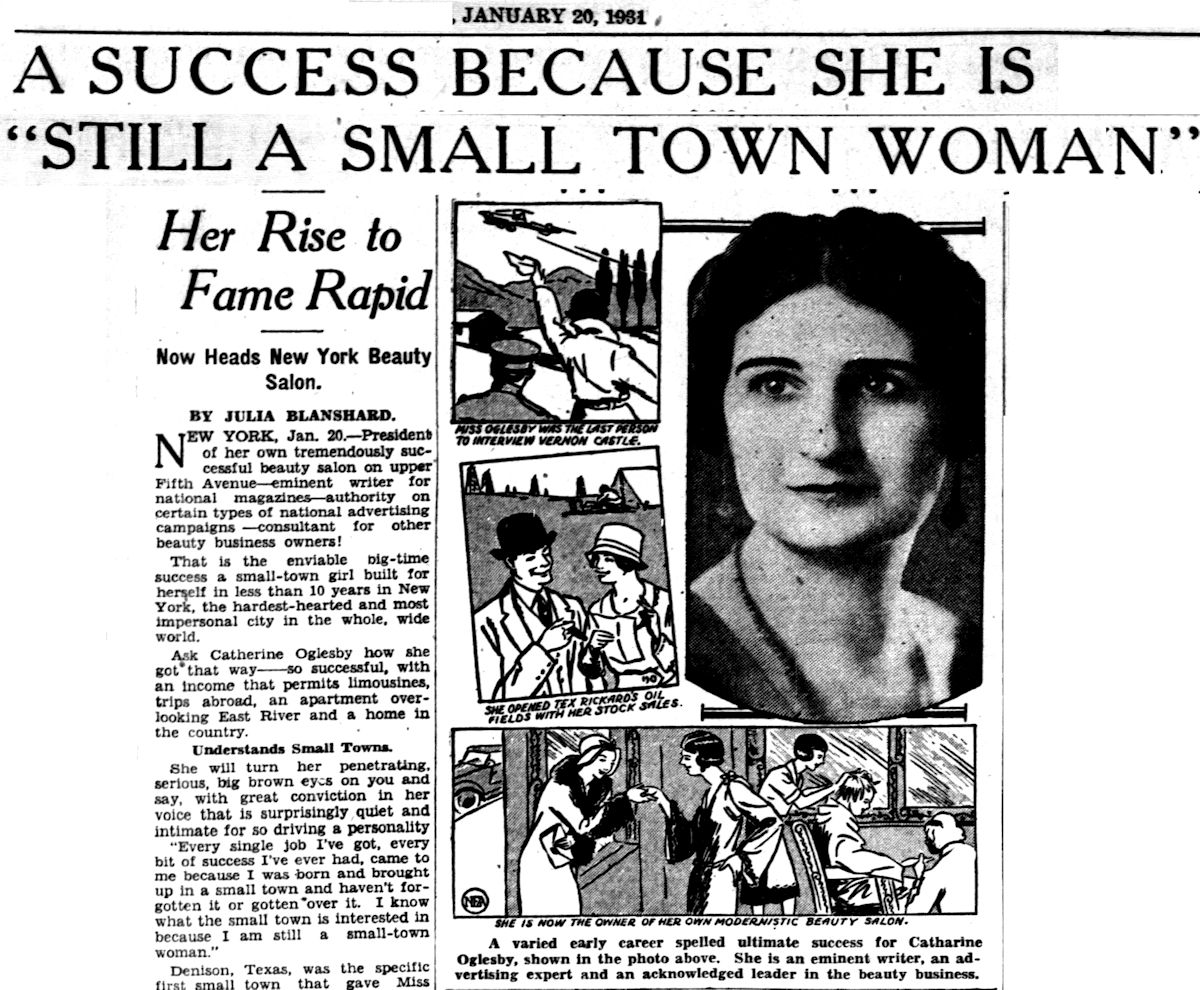

Years later she said: “Every single job I’ve got, every bit of success I’ve ever had, came to me because I was born and brought up in a small town and haven’t forgotten it or gotten over it. . . . I am still a small-town woman.”

Oglesby recalled that one of her first stories about Camp Bowie was a plea for blankets for the soldiers.

“The next night all the boys were under blankets,” she recalled.

Another early story was about a young soldier who was about to be sent overseas to the front. He confided to Oglesby that he was an orphan and was sad because he had no mother to see him off.

Oglesby said her front page story resulted in ninety-three mothers offering to adopt the young soldier.

Most of Oglesby’s Camp Bowie stories in the Star-Telegram archive are from 1919, written after the war had ended and Sammies were returning to Camp Bowie to be discharged.

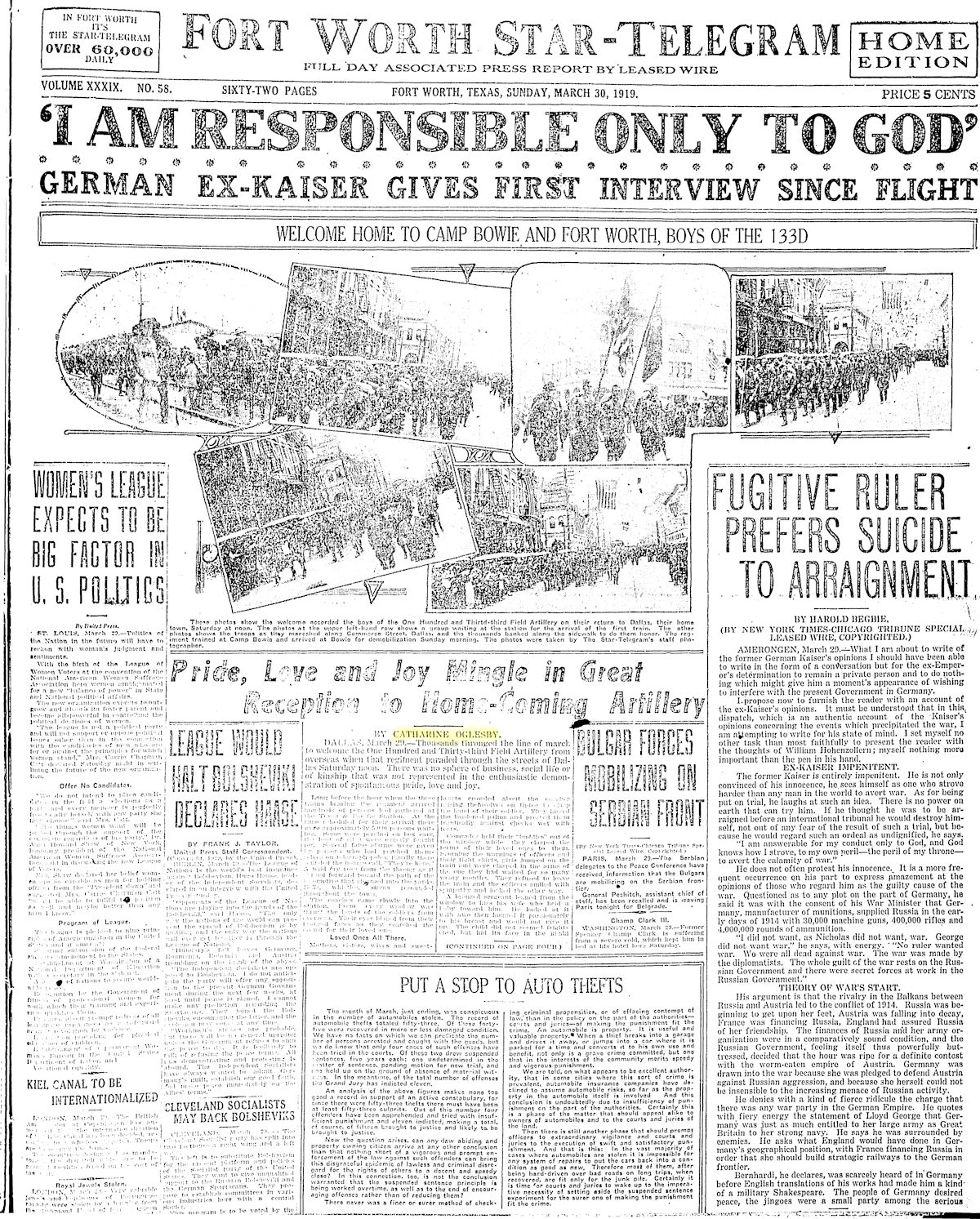

Oglesby wrote about the return “home” of the 133rd Field Artillery in 1919.

Oglesby wrote about the return “home” of the 133rd Field Artillery in 1919.

Oglesby wrote about a father and a son, both injured and hospitalized in France, who had been unaware that their hospitals were only 150 yards apart. Upon their return to the States, father and son were both patients in the base hospital at Camp Bowie but again unaware until a sergeant noticed the same last names, resulting in a reunion.

Oglesby wrote about a father and a son, both injured and hospitalized in France, who had been unaware that their hospitals were only 150 yards apart. Upon their return to the States, father and son were both patients in the base hospital at Camp Bowie but again unaware until a sergeant noticed the same last names, resulting in a reunion.

Oglesby wrote about a reunion of officers at Camp Bowie. The officers spoke of the bravery of their men in the trenches. One such man was Chaplain Crosiers:

Oglesby wrote about a reunion of officers at Camp Bowie. The officers spoke of the bravery of their men in the trenches. One such man was Chaplain Crosiers:

“Chaplain Crosiers won the title of the ‘Fighting Parson’ in the real sense of the word. He went over the top with the One Hundred and Forty-second Infantry. He buried men under shell fire, and some of the officers say that frequently they have seen him digging graves in No Man’s Land. A sniper would see him. The chaplain would have to get into the grave to protect himself from the bullets. But as soon as affairs quieted he would continue his work.”

Oglesby wrote about the assistant field director of the Red Cross at Camp Bowie, known as the “Trouble Man” by the Sammies who sought his help as they were preparing to leave the Army.

Oglesby wrote about the assistant field director of the Red Cross at Camp Bowie, known as the “Trouble Man” by the Sammies who sought his help as they were preparing to leave the Army.

The Trouble Man negotiated reconciliations between Sammies and wives who had separated, helped sons locate their parents, played matchmaker with shy soldiers and the object of their affection, helped couples find homes and jobs.

“His duties include those of Hymen [Greek god of marriage ceremonies], Cupid, and Midas. To insure their success he seems to possess the peculiar genius of detectives, consolers, and ministers.”

Oglesby wrote about the Army’s efforts to counsel and train soldiers who returned from the war with injuries—lost limbs, diminished strength, impaired vision or hearing, etc.—that kept them from resuming their civilian job.

Oglesby wrote about the Army’s efforts to counsel and train soldiers who returned from the war with injuries—lost limbs, diminished strength, impaired vision or hearing, etc.—that kept them from resuming their civilian job.

For example, one soldier who had been a farmer could no longer walk behind a plow. He would be taught to drive a tractor.

Mustard gas had partially blinded a locomotive engineer. He would never drive a locomotive again, but he would be trained to inspect railroad airbrake systems.

Another soldier had been a print shop pressman, but he had lost the use of one hand in the war. Now he would be taught to plan pamphlets and books, using his knowledge of the printing trade.

Still another soldier had been a meatcutter. But during the war he developed heart trouble and could no longer lift heavy weights. He would be trained as a meat inspector.

Catharine Oglesby met them all.

Ironically, she later said of her year covering Camp Bowie: “I was the only girl in the world too busy to have a date with a soldier.”

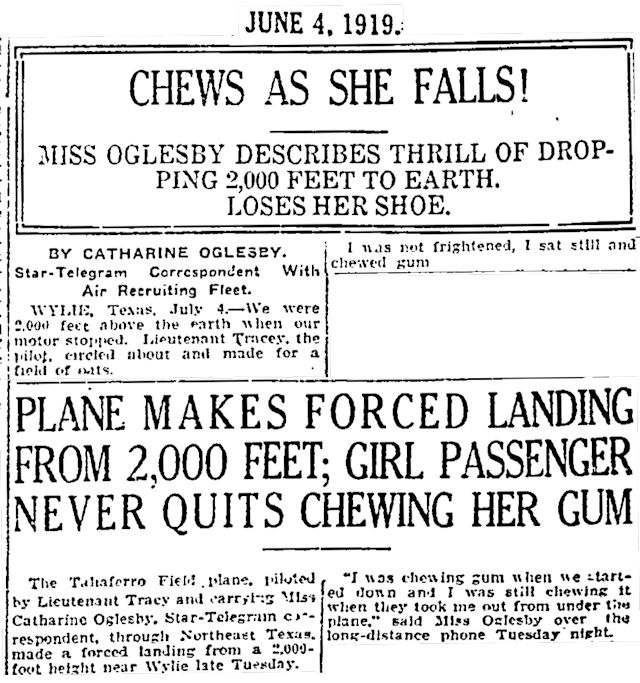

The war was over, but the Army needed recruits to replace soldiers being discharged. Oglesby accompanied Army recruiters as they flew from Camp Taliaferro to cities in north Texas seeking men to join the Army’s aviation service. On one flight the engine of the airplane that Oglesby was flying in stopped at two thousand feet. As the airplane descended at sixty miles per hour, Oglesby continued to chew her gum.

The war was over, but the Army needed recruits to replace soldiers being discharged. Oglesby accompanied Army recruiters as they flew from Camp Taliaferro to cities in north Texas seeking men to join the Army’s aviation service. On one flight the engine of the airplane that Oglesby was flying in stopped at two thousand feet. As the airplane descended at sixty miles per hour, Oglesby continued to chew her gum.

The pilot made an emergency landing in a field of oats. The plane flipped over, but the pilot and Oglesby were not injured.

In fact, she wrote, she was still chewing her gum.

Oglesby’s status as a “girl reporter” a century ago was unusual enough that the newspaper capitalized on it.

Oglesby’s status as a “girl reporter” a century ago was unusual enough that the newspaper capitalized on it.

As the Sammies went home and Camp Bowie was demobilized, Oglesby pointed her pencil west to Ranger. She told her editor, James R. Record, that she wanted to go to the oil fields.

She recalled: “Mr. Record said, ‘You may go if you wish, but I will not send you.’ So I went.”

She “saved up $15.50” and went west in search of still more human interest stories.

“When I got there, there were no hotel rooms. One man said to me, ‘You can have my room, sister.’ So I haughtily told him to call a bellboy and have my bags sent up.

“Of course, there weren’t any bellboys,” she recalled.

“He volunteered to take my bags up. I tipped him a dime.”

The man turned out to be sports promoter Tex Rickard. Rickard, like so many others, had been lured to Ranger by the oil boom. By 1919 he had three oil companies in Texas.

Oglesby would develop a friendship with Rickard that soon would point her pencil in still another direction.

Oglesby toured Ranger and the oil fields, talking to the people caught up in the rags-to-riches romance of the boom.

For example, she wrote about M. H. Hagaman, who had taught school in Ranger thirty-one years. Then he had become a carpenter, had built many of the buildings that in 1919 were being torn down as Ranger was being transformed by the oil boom.

For example, she wrote about M. H. Hagaman, who had taught school in Ranger thirty-one years. Then he had become a carpenter, had built many of the buildings that in 1919 were being torn down as Ranger was being transformed by the oil boom.

After trying his hand at carpentry, Hagaman had bought a small farm. He needed to dam a small stream to impound a lake to irrigate his fields. But he lacked the money.

Then, soon after oil was discovered on the farm of J. H. McCleskey, three wells on Hagaman’s farm struck oil.

Then, soon after oil was discovered on the farm of J. H. McCleskey, three wells on Hagaman’s farm struck oil.

Suddenly he was rich. He could afford to dam that stream.

And he began to sell the water to the oil drillers.

Now he was making money from oil and water.

Oglesby wrote that Hagaman planned to pump some of that water to Ranger, which suddenly needed more of everything.

Oglesby wrote about a farmer near Ranger who before the McCleskey well came in had been offered seventy-five cents an acre to lease his land to an oil company. He had consented. But the title to the land had not been clear. The lease could not be finalized. The farmer was disappointed.

Oglesby wrote about a farmer near Ranger who before the McCleskey well came in had been offered seventy-five cents an acre to lease his land to an oil company. He had consented. But the title to the land had not been clear. The lease could not be finalized. The farmer was disappointed.

By the time the McCleskey well came in, the title had been cleared up. And the price paid for oil leases had skyrocketed. The farmer leased his land for $3,000 an acre.

A man who eked out a living as a “scavenger” in Ranger leased his little plot of land to an oil company. A well came in. The former scavenger’s income suddenly was $900 ($13,000) a day.

Oil was not the only way to get rich in Ranger. J. W. Cooper owned a tract of land east of town. But drilling proved that the land held no oil. So, he platted the land into lots for housing and got rich as real estate values around Ranger soared. People were sleeping in the open because of the housing shortage.

A man who had lost both legs had leased a plot of ground from the owner for five years for $500. After two years the oil boom began, and the owner of the land offered the legless man $150,000 for the remaining three years of the lease.

The legless man’s response: “If you offered me $200,000 I might consider it.”

He was getting rich collecting rent from people who had thrown up shacks on the property when the boom began.

A fortune teller in Kentucky had told John Jones that he should move to Texas and buy a farm with a sandy hill on it. If he did, she said, he would become rich. Jones moved to Texas and bought a farm west of Ranger. It had a sandy hill. Three oil wells were brought in. The fortune teller had indeed foretold a fortune.

A man bought a lease near Ranger for $2,700. A well was drilled but proved to be a duster. Disgusted, the man told a soldier from Camp Bowie that he would sell him the lease for $1 for every $100.

The soldier gave the man $27.

Then the soldier bought a share of an adjacent lease. A well—deeper than the duster—was drilled. It came in. The Army private drawing $30 a month was now worth $50,000.

How much had the boom changed Ranger? How crazy had things gotten? Mr. and Mrs. Slayden were deaf mutes who lived on a farm near Ranger. They leased the land to an oil company. A well was brought in. The two deaf mutes took their money and moved away from Ranger, saying they couldn’t stand the excitement anymore.

Meanwhile in Toledo, Ohio sports promoter Tex Rickard, whom Oglesby had met in Ranger, was promoting the July 4, 1919 fight between world heavyweight boxing champion Jess Willard and challenger Jack Dempsey.

Meanwhile in Toledo, Ohio sports promoter Tex Rickard, whom Oglesby had met in Ranger, was promoting the July 4, 1919 fight between world heavyweight boxing champion Jess Willard and challenger Jack Dempsey.

Oglesby went to Toledo to cover the fight.

Among other writers covering the fight were Damon Runyon, Bat Masterson, and Ring Lardner.

Among other writers covering the fight were Damon Runyon, Bat Masterson, and Ring Lardner.

The “small-town woman” confided to Ring Lardner that she wanted to be a New York City newspaperwoman.

Oglesby recalled years later: “Tex never told me Ring Lardner was a humorist. So, when he [Lardner] fixed his serious eyes on me and said, ‘Young woman, New York is just waiting for you.’ I believed him.”

Lardner was being facetious. But Oglesby took him seriously.

In Toledo she bet all of her savings on Dempsey, who defeated Willard. She resigned from the Star-Telegram and used her winnings to finance a trip to New York.

But she didn’t go alone.

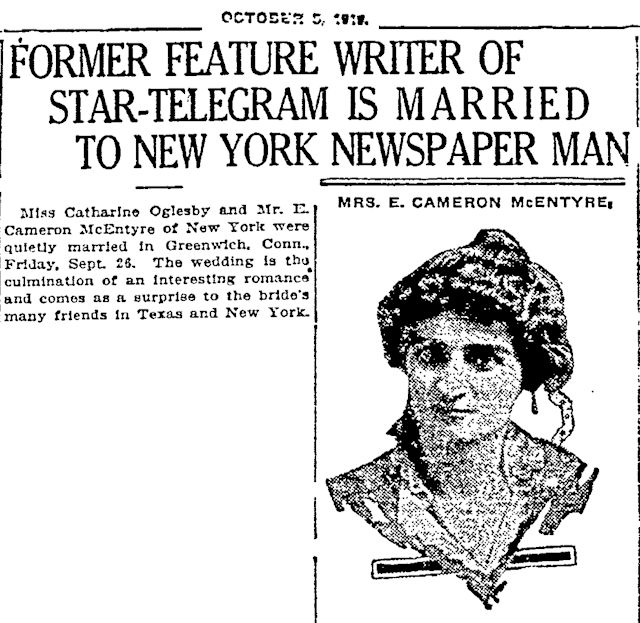

In spring of that year she had met newspaperman E. Cameron McEntyre of the New York Herald and Evening Telegram while both were covering the oil boom. The two journalists collaborated on a human interest story of their own: In September they were married and took up residence in New York City.

In spring of that year she had met newspaperman E. Cameron McEntyre of the New York Herald and Evening Telegram while both were covering the oil boom. The two journalists collaborated on a human interest story of their own: In September they were married and took up residence in New York City.

Oglesby opened a beauty salon on 5th Avenue, became advertising manager for Elizabeth Arden, was an associate editor of Ladies’ Home Journal.

By 1931 Oglesby was making a name for herself in New York. The Newspaper Enterprise Association syndicate distributed a feature about Oglesby that included a cartoon panel illustrating her achievements.

By 1931 Oglesby was making a name for herself in New York. The Newspaper Enterprise Association syndicate distributed a feature about Oglesby that included a cartoon panel illustrating her achievements.

In New York she wrote books on careers in fashion, French provincial decorative art, primitive arts.

She also worked for the J. Walter Thompson public relations firm, whose success made it as well known as the people and companies it promoted.

And then, in 1938 Catharine Oglesby broke another glass ceiling:

She became the first woman in America to found her own advertising company.

She later opened branch offices in London and Paris.

“I was the first woman to open an advertising agency, and they told me it couldn’t be done,” she recalled.

The “small-town woman” had succeeded in the biggest big city. She lived in an apartment overlooking the East River, had a second home in the country.

By the 1940s she and E. Cameron McEntyre had divorced, and Oglesby married Fred Hughes, who owned an advertising agency in Rochester.

After operating her own ad agency twenty years, Oglesby retired to paint and travel.

She had a “great love of adventure and curiosity” and traveled the world: Europe, Africa, Asia.

In Africa she ventured to a remote mountain range guided by two indigenous people and later was told that only one in five tourists returns alive.

“I had a marvelous time. I gave all my brassieres to the women. They’d never seen any.”

In 1968 Oglesby returned to Fort Worth for the first time since 1919. She spoke about “The 18th Century of Great Design” to the Fort Worth Art Association.

In 1968 Oglesby returned to Fort Worth for the first time since 1919. She spoke about “The 18th Century of Great Design” to the Fort Worth Art Association.

Catharine Oglesby, “girl reporter” and glass ceiling smasher, died in 1982.

Catharine Oglesby, “girl reporter” and glass ceiling smasher, died in 1982.

She is buried in Denison.

She is buried in Denison.

More from the “girl reporter”: $103 Million and “a New Set of Teeth”