C. C. Cummings was among Fort Worth’s early historians. He came by his interest in the past the hard way: He fought in some of the bloodiest battles of a historic war.

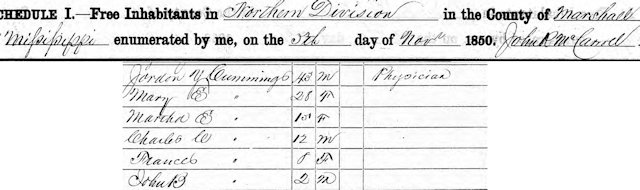

Charles Caldwell Cummings was born in Holly Springs, Mississippi in 1838. His father was a physician.

Charles Caldwell Cummings was born in Holly Springs, Mississippi in 1838. His father was a physician.

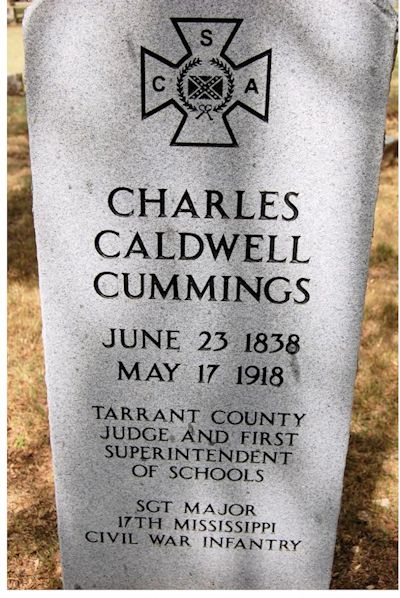

Fast-forward to April 12, 1861. The Confederate army fired on the Union’s Fort Sumter. Three days later Cummings enlisted in Mississippi’s 17th Regiment (infantry). He was twenty years old.

Fast-forward to April 12, 1861. The Confederate army fired on the Union’s Fort Sumter. Three days later Cummings enlisted in Mississippi’s 17th Regiment (infantry). He was twenty years old.

Then Cummings, along with thousands of other young men, began a tour of the sunny South with a rifle on his shoulder: He fought at First Manassas, Leesburg, Sharpsburg, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville.

So far, so good.

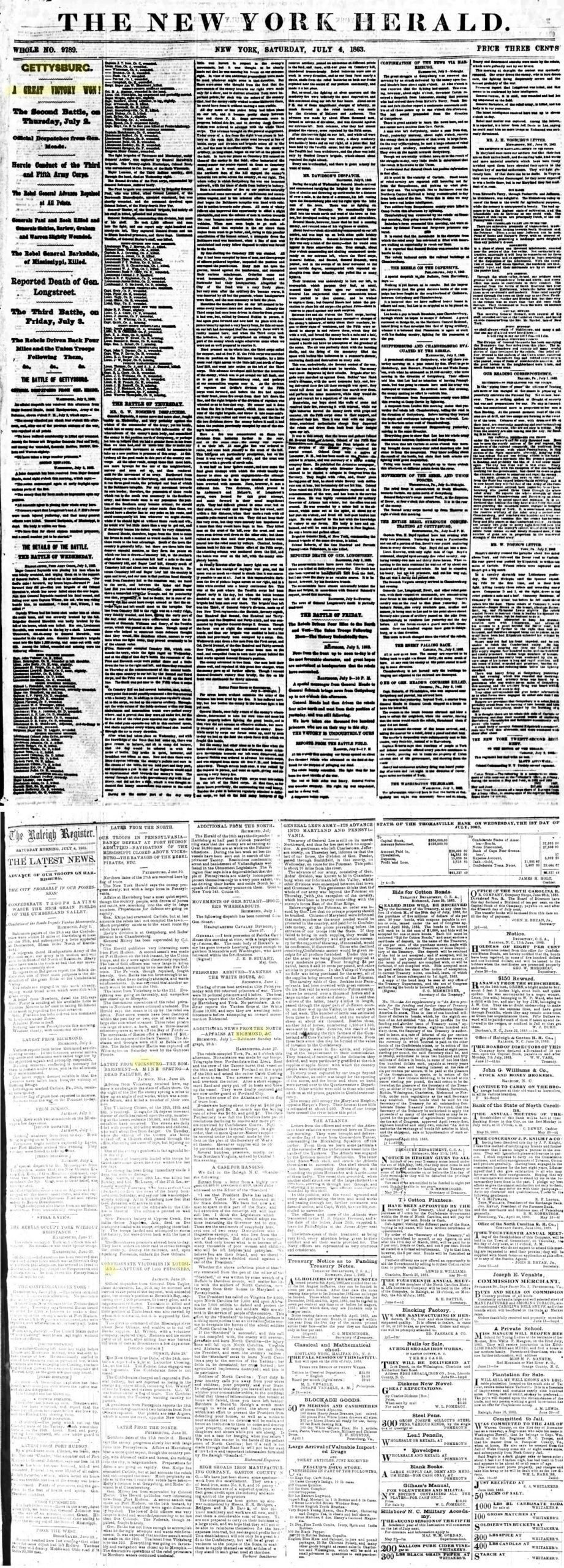

Then came an excursion north to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania and an idyllic-sounding place: Peach Orchard. Reverend Joseph Sherfy had planted the orchard several years earlier. All his hard work was about to be blown to splinters on July 2, 1863.

Sergeant Major C. C. Cummings later recalled the battle at Peach Orchard:

“We stood together on that fatal 2nd of July, 1863, looking down into the valley of death in the Peach Orchard at Gettysburg from 8 o’clock in the morning till about 4 p. m. in the afternoon, on Seminary Ridge, awaiting the order to rush down on [General Daniel] Sickles with his bloody angle of 10,000 men in blue with munitions of artillery and all the latest improved arms, which our single thin gray line was ordered to break and scatter, but at a cost of 275 of the 448 men in ranks of our regiment, 17th Mississippi Infantry. I was sergeant major of the regiment and numbered the guns going in, outside of the officers. In two hours these 275 were put out of action and when the night came there was gathered in a single tent on that field of glory all the field and staff of the regiment except Dick Jones, killed dead on the field—that is, Col. Holder wounded in the groin, Lieut. Col. Fizer wounded in the head, Sergt. Major Cummings, a similar wound in the hand and the orderly of the Col. Brown Jones, disabled also. When shot I was making for a battery in front which I failed to reach, but Billy [Abernathy] heard the order to go for it and was among the captors of this death dealing machine of war and was shot off one of the cannons of the enemy after waving his hat in victory astride it.”

Cummings was among the 43 percent of the men of the 17th Mississippi who were disabled at Gettysburg.

In 1904 the Star-Telegram wrote about Cummings’s experience at Gettysburg: “He was wounded and captured and lay on the battlefield until the maggots so infested his wound that his life was despaired of and he avers he would have died if not for the abuse of a Pennsylvania Dutchman, which so revived his combative spirit that he arose on his elbow and said: ‘Death avaunt [go away]. I will live to fight the battles of my country again.’

“The Dutchman’s wife took pity and gave him apple butter and made a concoction of alder leaves, which she poured on his wounds and killed the creeping things in his flesh.”

Newspapers in the Union crowed about the victory at Gettysburg. Newspapers in the Confederacy focused on news from elsewhere in the war: Vicksburg, Louisiana, Richmond.

Newspapers in the Union crowed about the victory at Gettysburg. Newspapers in the Confederacy focused on news from elsewhere in the war: Vicksburg, Louisiana, Richmond.

At Gettysburg, Cummings was among two thousand Confederates taken prisoner and held at Chester, Pennsylvania. They were soon exchanged for Union POWs.

With the loss of his hand (arm, some sources say) Cummings returned to Mississippi and served in a noncombat role until the end of the war.

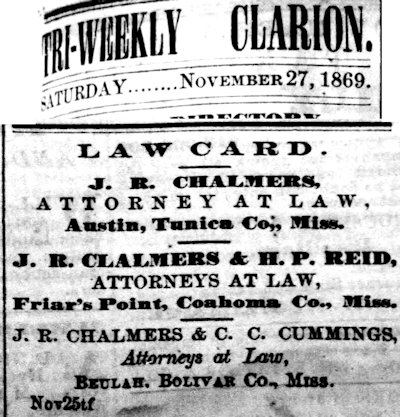

After the war Cummings earned a law degree from Cumberland University in Lebanon, Tennessee.

After the war Cummings earned a law degree from Cumberland University in Lebanon, Tennessee.

He begin the practice of law at Memphis in 1866 and then in his native Mississippi. In late 1872 he sailed down the Mississippi River to New Orleans and sailed on a steamer to Galveston. From Galveston he rode a stagecoach to Fort Worth, arriving in January 1873. Cummings had heard that Fort Worth was a wild and woolly place. He brought with him a shotgun, Bowie knife, and pistol but soon found no need for them.

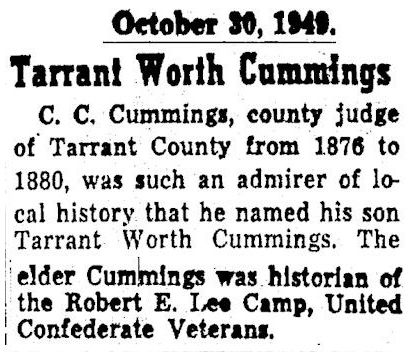

The year 1876 was doubly eventful for Cummings. First, his second son was born. Cummings was so taken with the history of his new home that he named the boy “Tarrant Worth Cummings.”

The year 1876 was doubly eventful for Cummings. First, his second son was born. Cummings was so taken with the history of his new home that he named the boy “Tarrant Worth Cummings.”

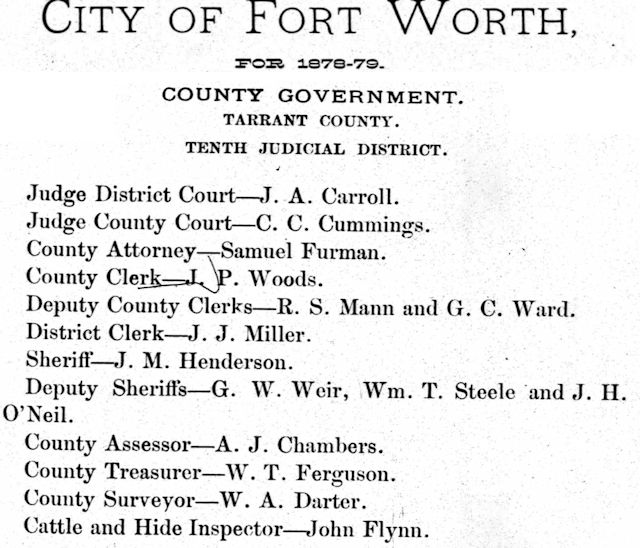

Also that year Cummings was elected county judge.

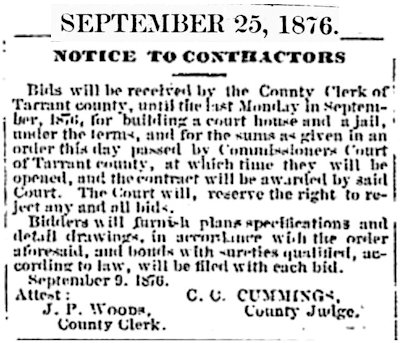

Cummings was elected soon after the 1860 courthouse burned on March 29, 1876. He advertised for bids to rebuild the courthouse.

Cummings was elected soon after the 1860 courthouse burned on March 29, 1876. He advertised for bids to rebuild the courthouse.

School districts did not yet exist. Part of his job as county judge was to superintend schools in the county and educate people about new laws in the 1876 constitution regarding public schools. On Sundays he traveled by horse to communities and held meetings in churches. If no church was available, he held his meeting in the shade of a tree.

He was re-elected in 1878.

Outside the practice of law, Cummings had two passions: the Civil War and local history.

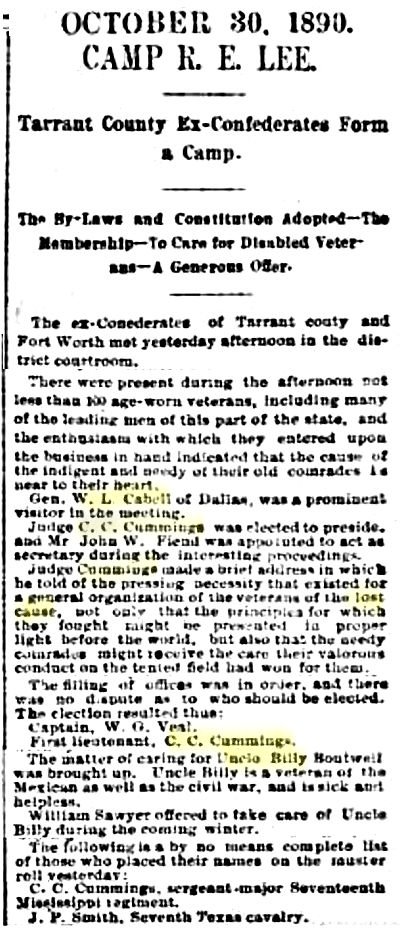

His experience in the Civil War profoundly affected Cummings. In 1890 Cummings was a founder of the local “camp” of the United Confederate Veterans, a group that had formed in 1889. Camp R. E. Lee, Cummings said, was being formed with two missions in mind: (1) to care for indigent veterans of the “lost cause” (such as Uncle Billy, who was also a veteran of the Mexican-American War) and (2) to ensure that “the principles for which they fought” were “presented in proper light before the world.”

His experience in the Civil War profoundly affected Cummings. In 1890 Cummings was a founder of the local “camp” of the United Confederate Veterans, a group that had formed in 1889. Camp R. E. Lee, Cummings said, was being formed with two missions in mind: (1) to care for indigent veterans of the “lost cause” (such as Uncle Billy, who was also a veteran of the Mexican-American War) and (2) to ensure that “the principles for which they fought” were “presented in proper light before the world.”

Also addressing the local veterans as the camp organized was General William Lewis “Old Tige” Cabell, the first of three Cabells to be mayor of Dallas.

Also joining the new “camp” was John Peter Smith.

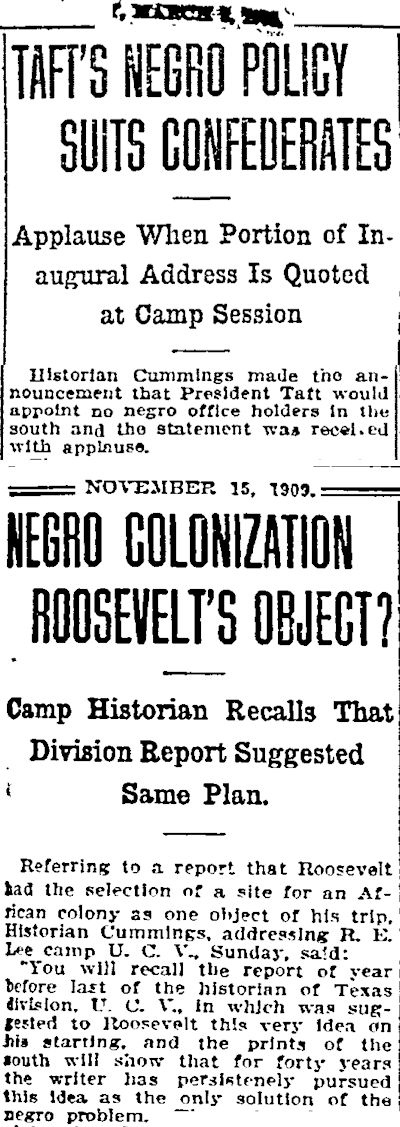

The “lost cause” that Cummings referred to in 1890 is an ideology that holds that the cause of the Confederacy was noble and just and endorses the virtues of the antebellum South. As these two clips of 1909 show, Cummings and many other Confederate veterans may have worn gray uniforms, but they continued to see the world in black and white.

The “lost cause” that Cummings referred to in 1890 is an ideology that holds that the cause of the Confederacy was noble and just and endorses the virtues of the antebellum South. As these two clips of 1909 show, Cummings and many other Confederate veterans may have worn gray uniforms, but they continued to see the world in black and white.

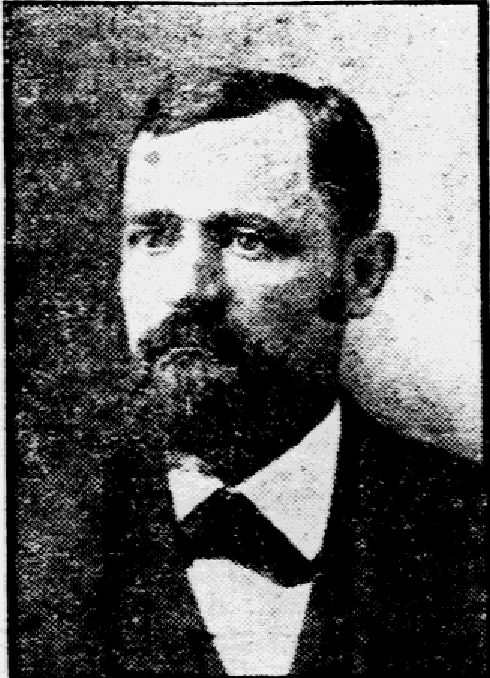

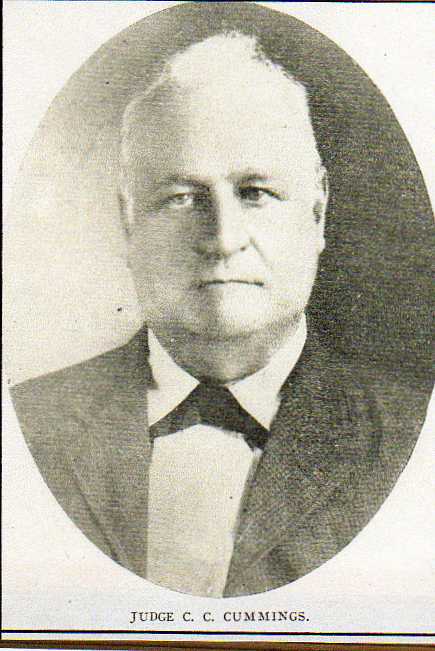

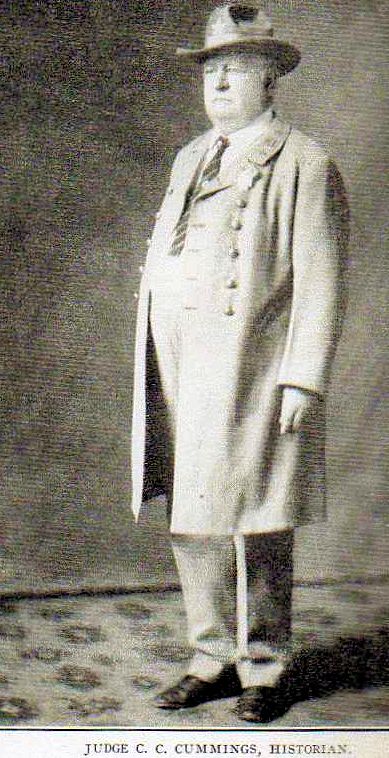

Cummings served as historian of the R. E. Lee Camp and eventually as historian of the United Confederate Veterans at the state level. (Photo from Confederate Veteran.)

Cummings served as historian of the R. E. Lee Camp and eventually as historian of the United Confederate Veterans at the state level. (Photo from Confederate Veteran.)

Cummings also had begun to write his ambitious history of Texas and Fort Worth, researching the printed word but also interviewing people who had lived the current events that became history—just as he had lived a war that became history.

History is where you find it, not just in books. Cummings was living when many of Fort Worth’s first residents were alive. He talked to them, wrote down their memories.

For example, one day in 1888 Cummings chanced upon George Preston Farmer, then seventy-one. Farmer and wife Jane had settled in Fort Worth before there was a Fort Worth.

Farmer told Cummings about building the first house in Fort Worth:

“It was made of logs. The ax did the work, the lone ax. The boards were riven [split] with it. I had no gear, or wagon, nor anything to haul with, so I tied the logs to my horse’s tail and dragged them to the spot where the first house was built, down there in Frank Twombly’s yard. My old woman handed the boards up to me, I fastened them down with log weights; we had no nails. I made us a bed with this same ax; took two upright pieces for bed legs, made out of saplings, stood them up in the corner of the cabin with a dirt floor, ran rough pieces for slats into the cracks of the wall, and our bed was made, at least the frame work. Prairie grass was much higher then than now, and it afforded ample material for stuffing the gunny sacks for a tick [bedding], and we got it done one evening just before dark. A rain was coming up (and it rained in Texas even at that early day); we got in under our shelter just in time to hear it splatter the roof, and maybe you don’t believe it was pleasant sleeping, listening to the rain without under our own vine and tree, or words to that effect. When the patter on the roof was at the hardest we heard a growling sound; it was outside. I peeped through the cracks and what do you reckon I saw amid the flashes of lightning? For it had a way of lightning here then all the same as now. It was a bear and a coyote. They were fighting over some beef bones that we had thrown out. We cooked out of doors under the shade of them nice live oaks down there in Frank Twombly’s yard, we did, wife and I.”

![]() Alas, that same year Cummings reported that Frank Twombly had torn down the first house built in Fort Worth.

Alas, that same year Cummings reported that Frank Twombly had torn down the first house built in Fort Worth.

Farmer also told Cummings that in 1849 he had been the person who suggested that the Army locate the site of its Fort Worth on the bluff:

“. . . and I can tell you just how Fort Worth was founded. It happened in this way: I was living there in that first house; my old woman was kinder poorly [another account says it was settler Ed Terrell who was poorly], and I went down to the Jim Woods place [Samuels Avenue], which Henry Holloway now owns, down in them live oaks north of town, near the race track [driving park], for the surgeon [civilian physician J. M. Standifer] of the post. The soldiers were camped there, and the doctor was an institution in their camps, the first doctor of the county. When we got along on the square where the court house now is I pointed out the spot to the doctor and told him if he would move his men up there it would stop them chills [malaria]. He did and the square was used as the drill ground . . .”

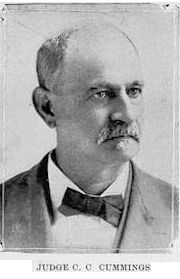

In 1899 Cummings was one of the founders of the Bohemian Club and wrote articles about history for The Bohemian magazine. (Photo from The Bohemian.)

In 1899 Cummings was one of the founders of the Bohemian Club and wrote articles about history for The Bohemian magazine. (Photo from The Bohemian.)

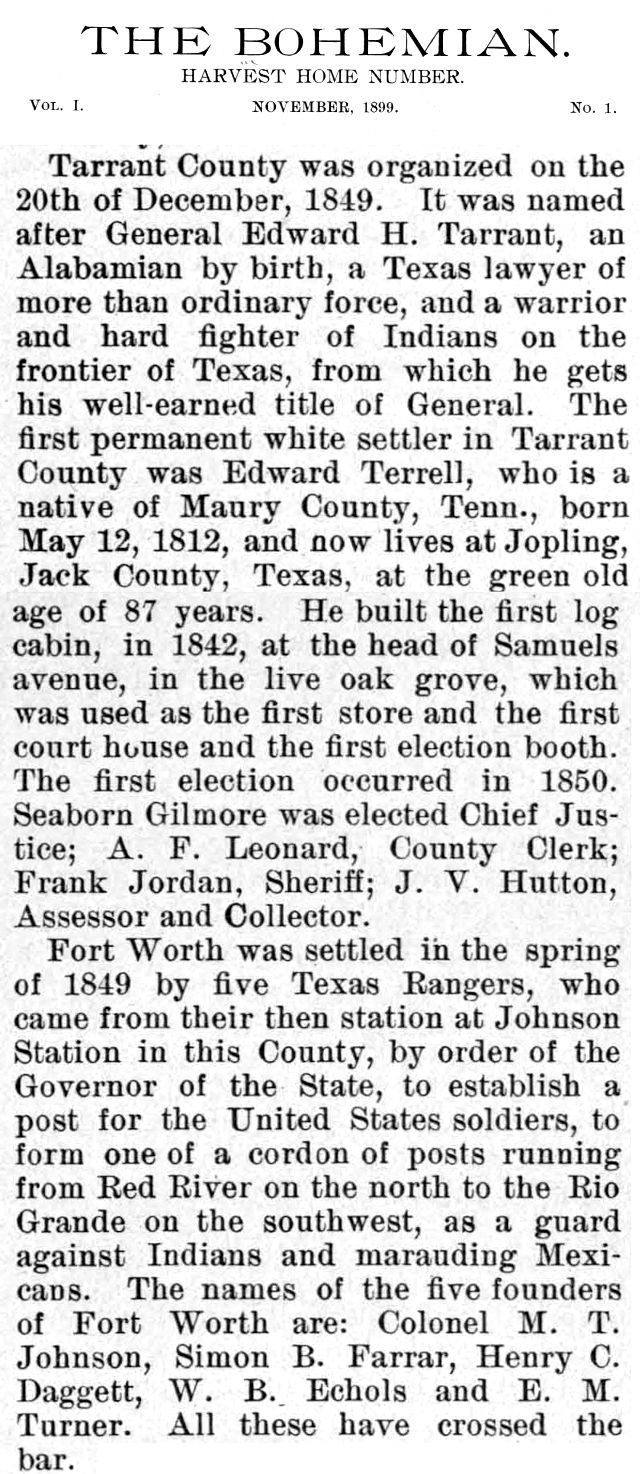

In the first edition of The Bohemian he wrote about organization of the county and selection of the site for the Army’s Fort Worth.

In the first edition of The Bohemian he wrote about organization of the county and selection of the site for the Army’s Fort Worth.

In 1904 Cummings wrote about Ed Terrell.

In 1904 Cummings wrote about Ed Terrell.

Cummings also reproduced and discussed several letters that Sam Houston wrote to Native American chiefs in preparation for the treaty meeting at Bird’s Fort.

Cummings also reproduced and discussed several letters that Sam Houston wrote to Native American chiefs in preparation for the treaty meeting at Bird’s Fort.

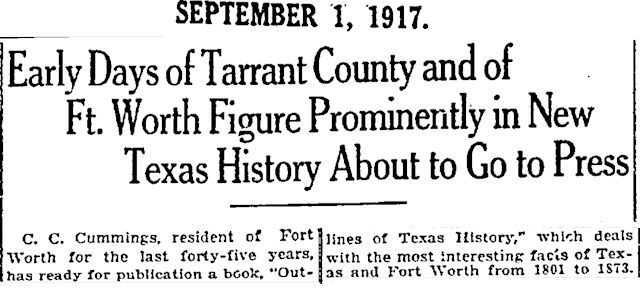

In 1908 the Star-Telegram reported that publication of Cummings’s history book was imminent. That report was premature.

In 1908 the Star-Telegram reported that publication of Cummings’s history book was imminent. That report was premature.

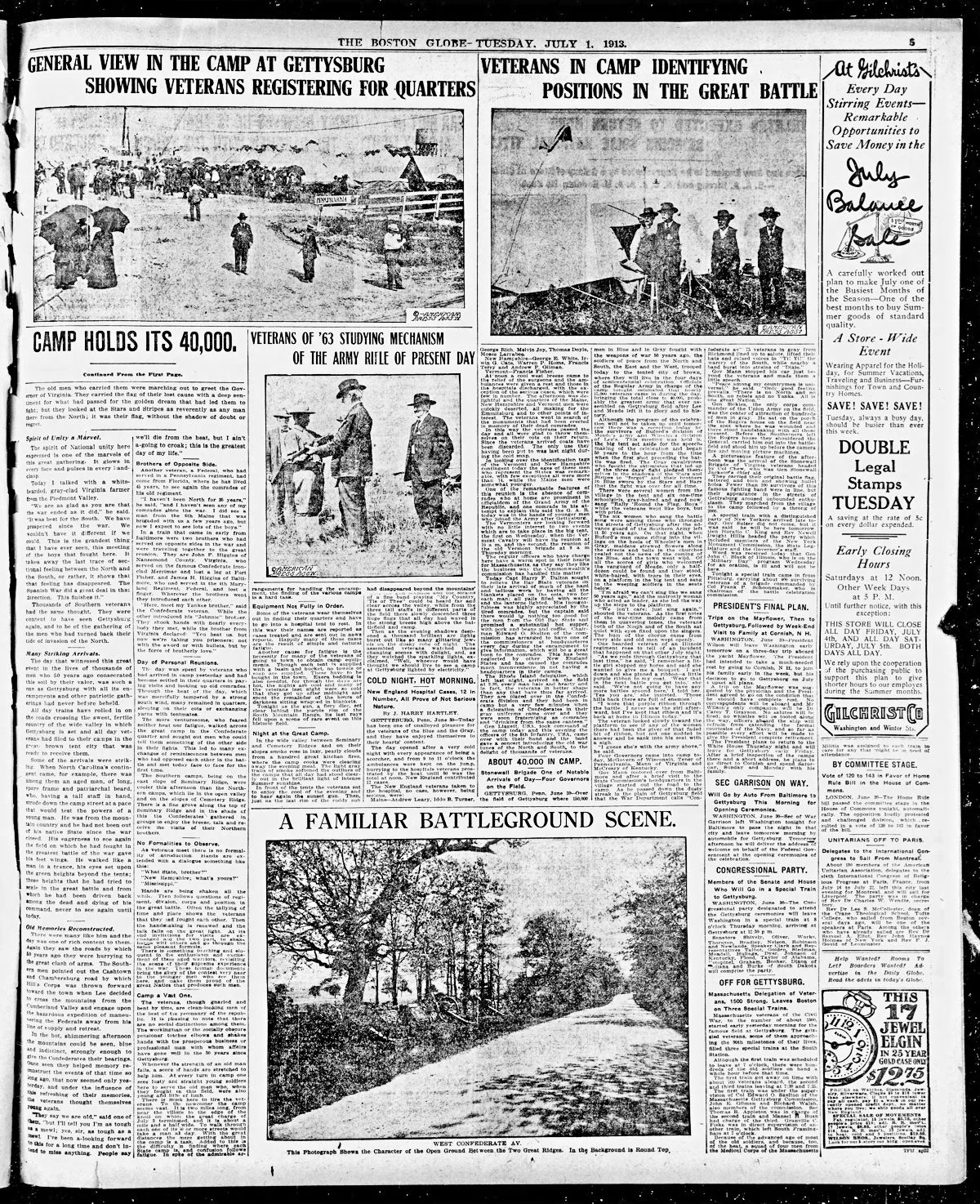

Fifty years after the Battle of Gettysburg a reunion of the blue and the gray was held at the battlefield. There Cummings met a Union soldier who had lost a leg at Gettysburg. The two shook hands, and Cummings said, “Here’s where I traded you my arm for your leg, Captain.”

Fifty years after the Battle of Gettysburg a reunion of the blue and the gray was held at the battlefield. There Cummings met a Union soldier who had lost a leg at Gettysburg. The two shook hands, and Cummings said, “Here’s where I traded you my arm for your leg, Captain.”

For a perspective on time, Civil War veterans in 1913 would have been about the age of Vietnam War veterans in 2021.

For a perspective on time, Civil War veterans in 1913 would have been about the age of Vietnam War veterans in 2021.

Film footage of the 1913 reunion from Ken Burns’s Civil War documentary

Cummings in his uniform. (Photo from Confederate Veteran.)

Cummings in his uniform. (Photo from Confederate Veteran.)

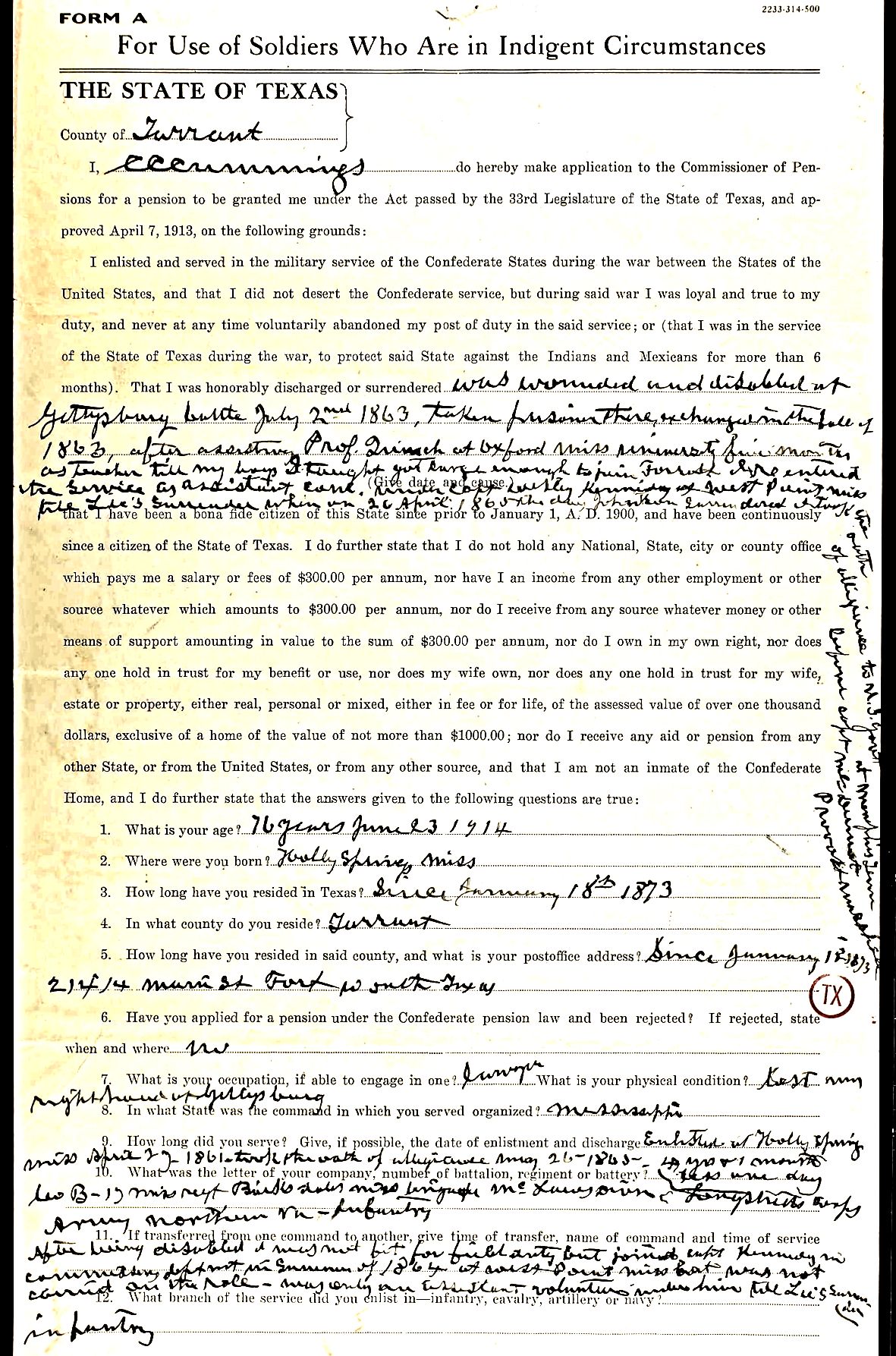

In 1914, at age seventy-six, Cummings applied for a Civil War pension.

In 1914, at age seventy-six, Cummings applied for a Civil War pension.

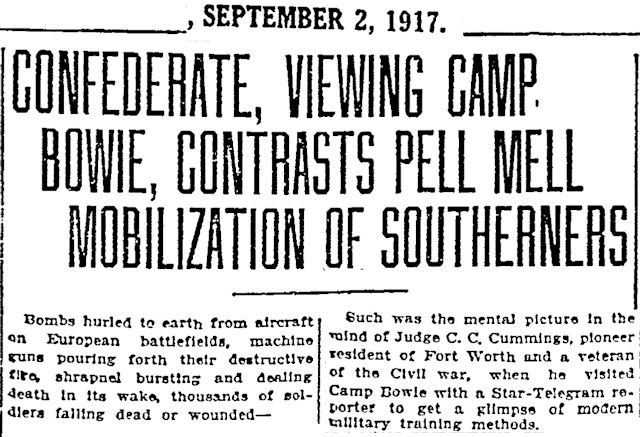

A new century brought a new war. In 1917, when he was seventy-nine, Cummings accompanied a Star-Telegram reporter to Camp Bowie to assess the changes in warfare fifty-four years after Gettysburg. The Star-Telegram wrote:

A new century brought a new war. In 1917, when he was seventy-nine, Cummings accompanied a Star-Telegram reporter to Camp Bowie to assess the changes in warfare fifty-four years after Gettysburg. The Star-Telegram wrote:

“. . . Military tactics, facilities, and conditions were different those days. Shrapnel, gas bombs, dum-dum bullets, hand grenades, poison gas, Zeppelins, and other modern tools of warfare were then unknown. The soldier of that yesteryear period had to rely upon his musket, squirrel gun, or whatever variety of weapon he found available. And according to Judge Cummings, uniforms were also at a premium. Those who could not obtain uniforms went in their civilian clothes. Some went barefoot.

“‘But,’ says Cummings, ‘the American soldier of today is furnished with an ample supply of clothing of very serviceable quality, and when it wears out, his wardrobe is restocked.

“‘Also, the twentieth-century Sammie has more accurate firearms at his command, and should his gun become lost or disabled, he is immediately provided with another. When I faced the shot and shell these modern conditions did not prevail. The soldier who lost his gun was indeed “out of luck.”

“‘The improvement in war methods since I shouldered a gun has been marvelous. . . . and general war science has advanced wonderfully. The arms are more accurate, and the whole system operates in clockwork schedule, thus saving much time, energy, and loss of life. We had no adequate hospitals, no labor-saving war implements, and we did not fight from trenches to any extent. The majority of the fighting was done in the open.’”

Once again in 1917 the Star-Telegram reported that publication of Cummings’s long-awaited history book was imminent. Once again the report was premature.

Once again in 1917 the Star-Telegram reported that publication of Cummings’s long-awaited history book was imminent. Once again the report was premature.

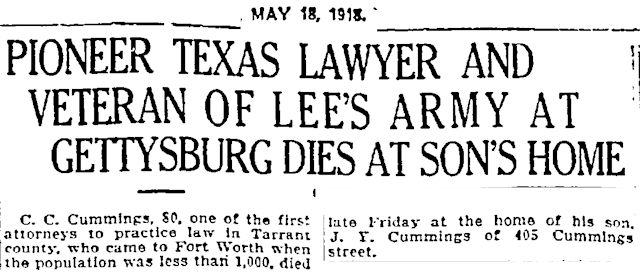

In 1918 the judge and his manuscript ran out of time. Charles Caldwell Cummings died at the home of his eldest child, whose house stood on the judge’s old homestead.

In 1918 the judge and his manuscript ran out of time. Charles Caldwell Cummings died at the home of his eldest child, whose house stood on the judge’s old homestead.

Fort Worth historian Mary Daggett Lake wrote of Cummings: “Being a pioneer himself, he knew what the early settlers in this part of the country endured and fought for to make Fort Worth what it is today. Truly his life was an inspiration and his death a benediction. ‘A braver soldier never couched lance; a gentler heart did never sway in court.’” (Shakespeare, King Henry VI)

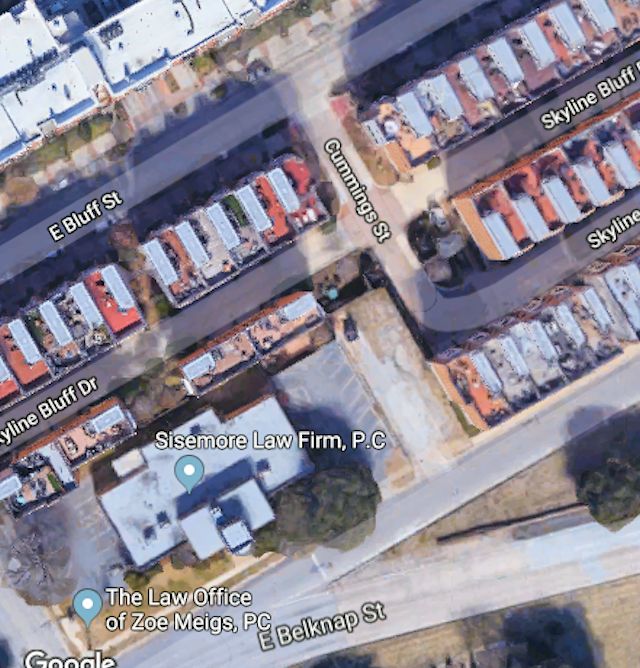

Cummings Street still exists in a maze of apartments between Bluff and Belknap streets downtown.

Cummings Street still exists in a maze of apartments between Bluff and Belknap streets downtown.

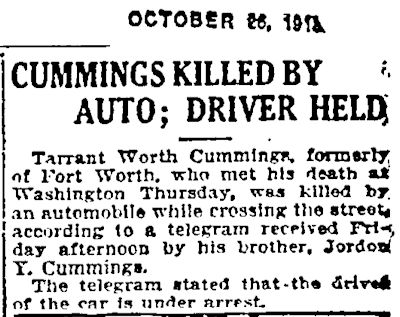

Death had not finished with the family of C. C. Cummings. In October son Tarrant Worth Cummings was killed by a car as he was crossing a street in Washington, where he worked for the Internal Revenue Service.

Death had not finished with the family of C. C. Cummings. In October son Tarrant Worth Cummings was killed by a car as he was crossing a street in Washington, where he worked for the Internal Revenue Service.

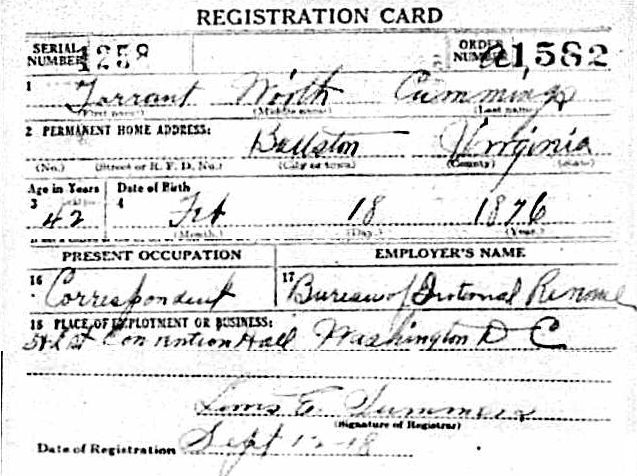

Six weeks earlier he had registered for his second war—he had served in the Philippines in the Spanish-American War.

Six weeks earlier he had registered for his second war—he had served in the Philippines in the Spanish-American War.

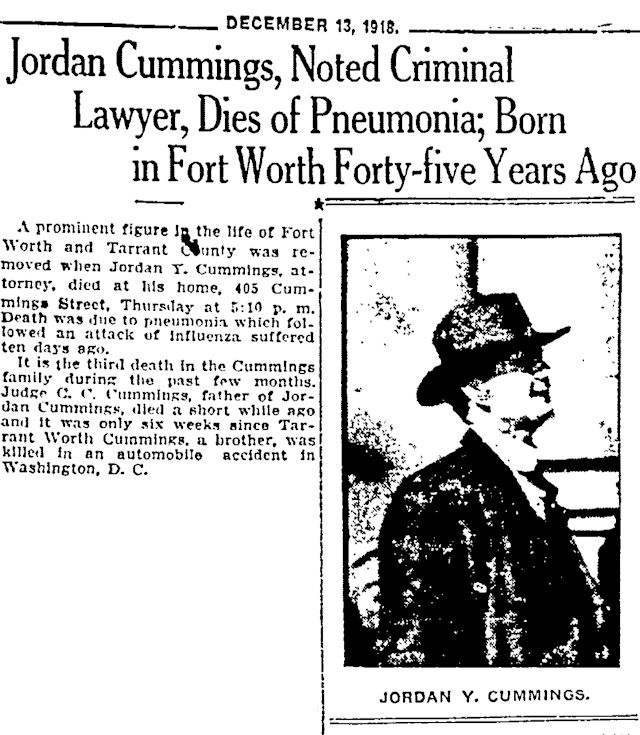

In December C. C. Cummings’s son Jordan Yarborough Cummings died of pneumonia. He was a prominent criminal lawyer, defending J. Frank Norris and Rufus Coates and helping prosecute John Sneed.

In December C. C. Cummings’s son Jordan Yarborough Cummings died of pneumonia. He was a prominent criminal lawyer, defending J. Frank Norris and Rufus Coates and helping prosecute John Sneed.

Soldier, judge, and historian Charles Caldwell Cummings fittingly is buried in Pioneers Rest Cemetery.

Soldier, judge, and historian Charles Caldwell Cummings fittingly is buried in Pioneers Rest Cemetery.

Is there a way for me to get a physical copy of this article.

C.C Cummings is my 2nd great grandfather.

Jordan Y. Cummings is my great grandfather.

Swayne Cummings is his son and my grandfather.

James Clayton Cummings (grandson of Jordan) is my father.

I was born James Clayton Cummings Jr. but mother remarried and was adopted by my step father and took his last name.

Very interesting article for me and the history of Fort Worth!

C. C. Cummings was a major figure in Fort Worth history. You can get a .pdf file of the text and images of a blog post by navigating to “print” in your browser (I am using Chrome) and selecting “destination: save as PDF.”