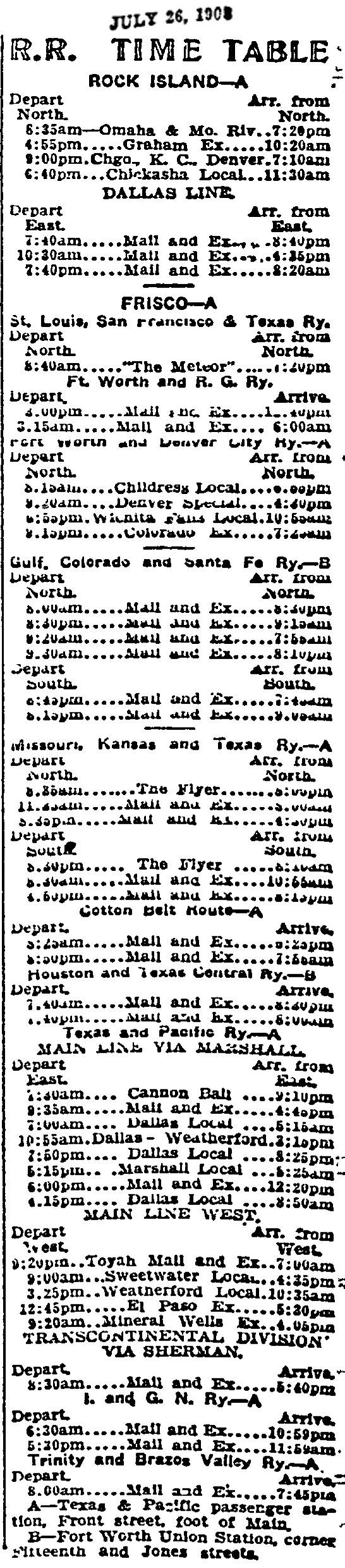

If you think traveling by airliner can be a challenge early in the twenty-first century, you can appreciate what a challenge traveling by train could be early in the twentieth century.

As the new century began, Fort Worth was served by nine railroads at two passenger stations: the Texas & Pacific and the Santa Fe, both opened in 1899. Train stations were the airports of the Iron Age: crowded, confusing, chaotic.

As the new century began, Fort Worth was served by nine railroads at two passenger stations: the Texas & Pacific and the Santa Fe, both opened in 1899. Train stations were the airports of the Iron Age: crowded, confusing, chaotic.

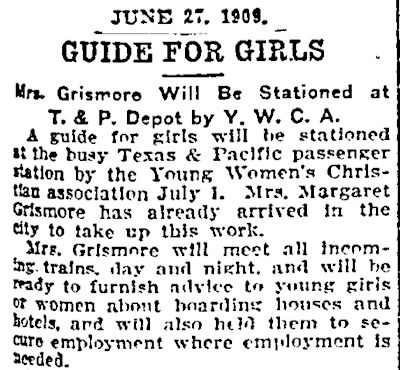

In 1909 the local YWCA began a program to assist one type of train passengers at the T&P station: A “guide for girls” service helped young female passengers traveling alone secure accommodations and employment.

In 1909 the local YWCA began a program to assist one type of train passengers at the T&P station: A “guide for girls” service helped young female passengers traveling alone secure accommodations and employment.

But that niche service quickly evolved into a travelers aid service for all passengers. Each day hundreds of passengers got off trains at the two stations, and many of them needed help: people overwhelmed by their first trip on a train, children traveling alone, elderly people, people with physical challenges, people who were the victim of theft and other crimes while traveling, people from foreign countries coping with a strange currency, customs, and language.

But that niche service quickly evolved into a travelers aid service for all passengers. Each day hundreds of passengers got off trains at the two stations, and many of them needed help: people overwhelmed by their first trip on a train, children traveling alone, elderly people, people with physical challenges, people who were the victim of theft and other crimes while traveling, people from foreign countries coping with a strange currency, customs, and language.

There to assist them all was the YWCA. Below is a sample of the kind of aid rendered by four angels of the Iron Age.

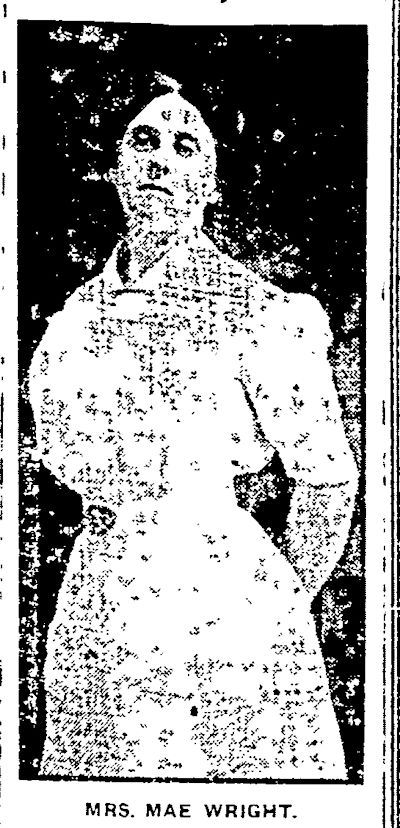

Mae Wright worked at the T&P station. In 1912 she aided 3,349 women and children.

Mae Wright worked at the T&P station. In 1912 she aided 3,349 women and children.

She gave the Star-Telegram a synopsis of her work: “We save many young girls from being insulted while waiting in the station. For there are officers [see below] near at hand ready to respond to our call. Our duties are not easy. We meet all trains and stand so we can see all who pass through the station. One must be strong, able to stand noise and confusion, exposed to cold and bad weather. . . . Aids must be intelligent and have tact and know how to be friendly and sympathetic and cheerful at all times. . . . We must deal with the foreigner—Polish, Greek, Swede—those who cannot talk our language and by signs make their wants known. Even those of our own nation, who can easily make their troubles known, come into our station, are bewildered and at their wits’ end. The troubles of the passenger are many. They lose their tickets or money. The person they expect to meet them doesn’t come; they have only a hazy recollection of the address to which they were going. They come seeking work in our town without money or friends, having no idea when or where a meal or a night’s lodging may be had or how their difficulties can possibly be solved.”

A century ago, in what many people today would consider reckless parenting, children were put onto trains to travel long distances unescorted. At best the children wore fastened to their clothing a tag bearing their name and contact information for the sending and/or receiving party.

A century ago, in what many people today would consider reckless parenting, children were put onto trains to travel long distances unescorted. At best the children wore fastened to their clothing a tag bearing their name and contact information for the sending and/or receiving party.

That was the case when Wright helped a girl of nine taking her first train trip—unescorted across six states.

Blind children attending the state school in Austin also passed through the T&P station.

Blind children attending the state school in Austin also passed through the T&P station.

When a boy of ten lacked the money to buy a ticket home to Chicago, Wright passed the hat among waiting passengers.

When a boy of ten lacked the money to buy a ticket home to Chicago, Wright passed the hat among waiting passengers.

She also helped a young Russian wife and a German girl.

She also helped a young Russian wife and a German girl.

And after a thief stole the pocketbook of a young German woman traveling from Galveston to Kansas City, Wright took her in.

And after a thief stole the pocketbook of a young German woman traveling from Galveston to Kansas City, Wright took her in.

Another angel at the T&P station was Mollie Wolf. In January 1910 she aided two hundred travelers.

Another angel at the T&P station was Mollie Wolf. In January 1910 she aided two hundred travelers.

Wolf helped siblings five and ten years old traveling two thousand miles on their own.

Wolf helped siblings five and ten years old traveling two thousand miles on their own.

And when a “penniless” girl of thirteen, traveling alone from Missouri, was not met at the station by her aunt, Wolf took the girl in.

And when a “penniless” girl of thirteen, traveling alone from Missouri, was not met at the station by her aunt, Wolf took the girl in.

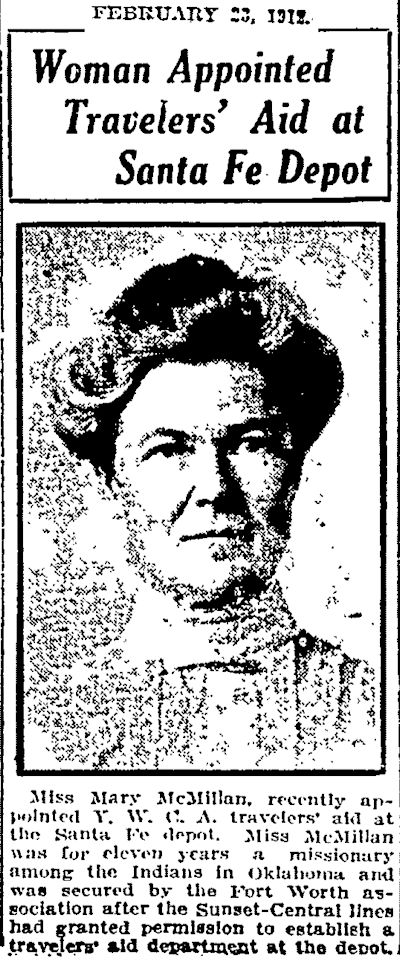

In 1912 the YWCA added a travelers aid service at the Santa Fe station. In the first year Mary McMillan aided twenty-five hundred travelers, mostly young girls traveling alone, mothers, the elderly, and the physically challenged.

In 1912 the YWCA added a travelers aid service at the Santa Fe station. In the first year Mary McMillan aided twenty-five hundred travelers, mostly young girls traveling alone, mothers, the elderly, and the physically challenged.

Eva Schooler had been on her own since she was ten, “roughing it,” riding freight trains, dressing as a man, associating with “hoboes” and “crooks.” She came to McMillan for help. “I’m tired of wandering about. I want to lead a different life.”

Eva Schooler had been on her own since she was ten, “roughing it,” riding freight trains, dressing as a man, associating with “hoboes” and “crooks.” She came to McMillan for help. “I’m tired of wandering about. I want to lead a different life.”

When a boy of eleven, traveling alone and “without funds,” was not met at the station by his sister, McMillan found accommodations for him until his sister could be located.

When a boy of eleven, traveling alone and “without funds,” was not met at the station by his sister, McMillan found accommodations for him until his sister could be located.

Young females traveling alone by train were a special concern of the YWCA’s travelers aid program because of “white slavery”: Predatory men befriended young girls traveling alone on trains and steered them into prostitution.

Young females traveling alone by train were a special concern of the YWCA’s travelers aid program because of “white slavery”: Predatory men befriended young girls traveling alone on trains and steered them into prostitution.

In 1913 Mary McMillan warned Justice Robert F. Peden that someone was providing girls with train tickets to various parts of the state. Authorities suspected that men working for hotels “of low character” were giving train tickets to girls so the girls could travel to the hotels, ostensibly to take legitimate jobs. McMillan feared that white slavers were taking advantage of a loophole in the federal anti-white slavery law, which outlawed sending girls to brothels but not to hotels.

So acute was the problem that in 1913 Universal Studios produced the film Traffic in Souls, portraying the social problem of white slavery.

So acute was the problem that in 1913 Universal Studios produced the film Traffic in Souls, portraying the social problem of white slavery.

Also in 1913 Fort Worth formed the Anti-White Slave Association because of growing concern that the city was becoming a center of white slavery.

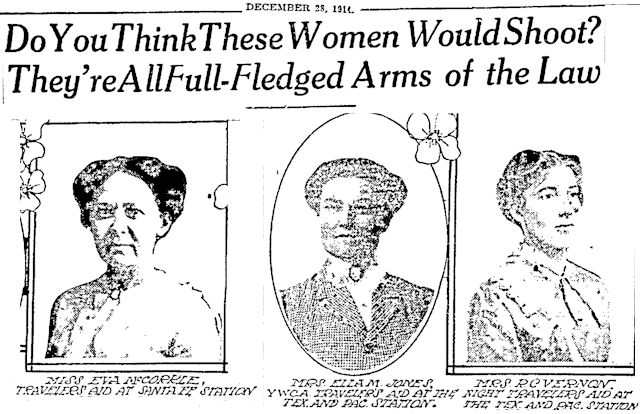

The Fort Worth Police Department also contributed to the social work performed at the train stations: The department commissioned three travelers aid workers as “special officers”: Eva McCorkle, Ella Jones, and Mrs. R. C. Vernon. These three women were angels with an edge: Each was issued a badge and a pistol and had all the powers of a police officer, including the power to arrest suspects and to detain potential victims of crime for their own safety.

The Fort Worth Police Department also contributed to the social work performed at the train stations: The department commissioned three travelers aid workers as “special officers”: Eva McCorkle, Ella Jones, and Mrs. R. C. Vernon. These three women were angels with an edge: Each was issued a badge and a pistol and had all the powers of a police officer, including the power to arrest suspects and to detain potential victims of crime for their own safety.

Ella Jones said of her pistol, which she kept in her desk drawer: “If it became necessary I would not hesitate a moment to use it. Usually a kind word turns away wrath. I might say that almost always the kind word turns away wrath, but if it should fall, and it came to this pistol I could blaze away without fear. I am afraid of no man, no matter what size or color because I know that in this work we have God on our side.”

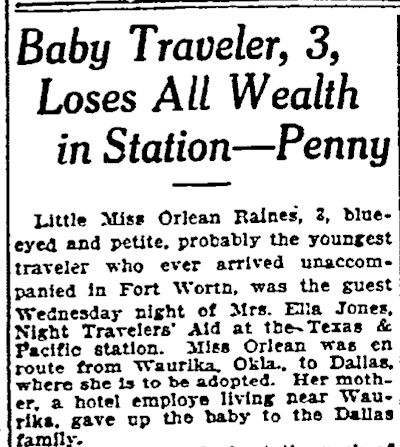

When a girl of three arrived unescorted at the station, Jones cared for her until the girl could travel on to Dallas for adoption. The child had one penny—all that was left of a quarter that a fellow passenger had given her on the train from Oklahoma.

When a girl of three arrived unescorted at the station, Jones cared for her until the girl could travel on to Dallas for adoption. The child had one penny—all that was left of a quarter that a fellow passenger had given her on the train from Oklahoma.

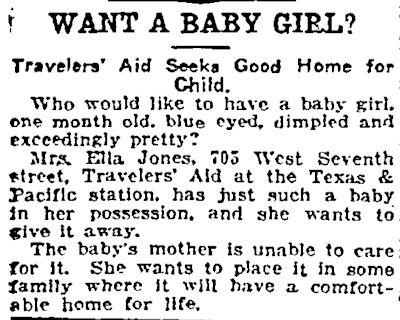

Jones also found herself the temporary guardian of a baby girl whose mother could not care for her.

Jones also found herself the temporary guardian of a baby girl whose mother could not care for her.

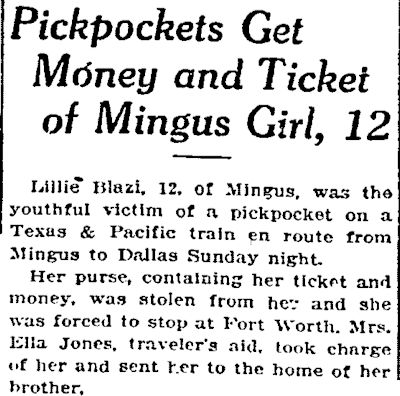

When a pickpocket stole the money and train ticket of a girl of twelve, Jones arranged for the girl to stay with the girl’s brother in Fort Worth.

When a pickpocket stole the money and train ticket of a girl of twelve, Jones arranged for the girl to stay with the girl’s brother in Fort Worth.

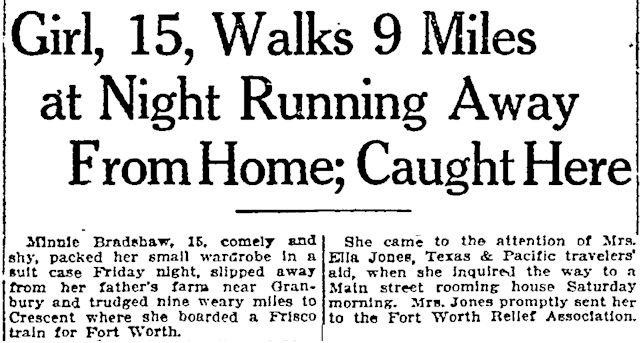

When a girl of fifteen ran away from home and got off the train at the T&P station, she told Jones that she had come to town to find work. But when Jones telephoned the girl’s father, he said she had run away from home to get married. Jones sent the girl to the Fort Worth Relief Association until her father could arrive to fetch her.

When a girl of fifteen ran away from home and got off the train at the T&P station, she told Jones that she had come to town to find work. But when Jones telephoned the girl’s father, he said she had run away from home to get married. Jones sent the girl to the Fort Worth Relief Association until her father could arrive to fetch her.

In 1916 special officer Jones aided 5,930 passengers at the T&P station. She kept a log of her activities. Here is a sample of her entries for August and September:

Aug. 4—Girl fainted in waiting room. I bathed her face and attended her until her train for Mineral Wells arrived.

Aug. 4—A passenger on Texas & Pacific train reported to me that a man had been flirting with a young girl on the train and they got off here. I found them. The man ran when I approached them. I kept the girl in the waiting room until her train came.

Aug. 11—Little girl from a [Fort Worth &] Denver train ran up to me at the gate and said a strange man had taken a seat beside her on the train and then followed her into the station. She pointed him out, but he walked hurriedly off when he saw me.

Aug. 19—Young girl came to my desk and asked if she could stay overnight on her ticket. I told her the ticket would not permit it and she returned to a seat. A man came up and began to talk to her. I took her into the ladies’ room and told her she must not talk to strange men. At first she said he was her husband. I knew better. Then she confessed he was a man she had met on the train, and he had asked her to stay over and go to a picture show. The man disappeared. I kept the girl until train time, and then placed her in charge of the conductor.

Aug. 20—Gladys B— came to me looking for a rescue home. She was without money. This was a sad case.

Aug. 28—Woman in Barstow wired me to meet her daughter, who was to change cars for Pilot Point. I recognized the girl and put her on the right train.

Aug. 29—I put a girl, 14, traveling alone and frightened, on a Texas & Pacific train.

Aug. 31—A woman, without money, with a very sick child, appealed to me. I did all I could for the child, and then put them on their train.

Aug. 31—Little girl, 8, arrived on train and no one was here to meet her. I tried all day before I located her relatives in Fort Worth. Another woman with three small children could not find her relatives. I finally located them.

Sept. 7—Saw a man talking to a young girl in the station. I called her off, and asked who the man was. She didn’t know, and that it was none of my business, anyway. I kept her until her train came.

Sept. 18—Put very ignorant country girl who had never been away from home before, on the [Fort Worth &] Denver train for Childress.

Sept. 19—Put a little girl, 8, on train for Longview. She had traveled all alone from Portland, Ore.

Sept. 28—Caught Nellie M— from Snyder who came here to meet a man she said was her brother-in-law. Finally said he was a man who was to meet her here and take her to Madill, Okla. I found a letter in her grip in which this man had sent her money with which to make the trip. I sent her to Relief Association, and her father was wired for. He came for her. She realized her mistake, and thanked me for what I had done before she left for home.

Sept. 29—Put old lady, 89, on Texas & Pacific train. She had slept in the station all night, making her a pallet with quilts on the floor of the waiting room.

Sept. 29—Assisted man with his paralyzed wife.

Sept. 30—Put girl, 7, who was totally blind, on the train for Austin.

Sept. 30—Took two girls, 14 and 18, away from two drunken soldiers, and put them on a street car for their homes.

In most cases a flash of the badge by Ella Jones and the other special officers was enough to cause men who approached young girls in a station to walk quickly toward the nearest “exit” sign.

In 1930, after twenty-one years of helping tens of thousands of passengers, the YWCA’s angels of the Iron Age passed the halo to the Travelers’ Aid Society, which operated under the auspices of the Community Chest. The society moved its operation to the new Texas & Pacific station when the station opened in 1931.

(Thanks to retired Fort Worth police sergeant and historian Kevin Foster for his help.)

Posts About Trains and Trolleys

Posts About Women in Fort Worth History

Wow! What a great story this is…or should I say “stories”? So many tales of hardships and helping one’s fellow man. Particularly apropos at this time of year.

Thanks, John.

Very excited to find your post. Mae Wright was my great grandmother. Her son, my grandfather, died when my father was very young and I’ve been learning more about the family that stayed behind in Texas(both her sons moved to California). I love reading about all the interesting people and scenarios that would befall the aids!

Thanks, Felicia.