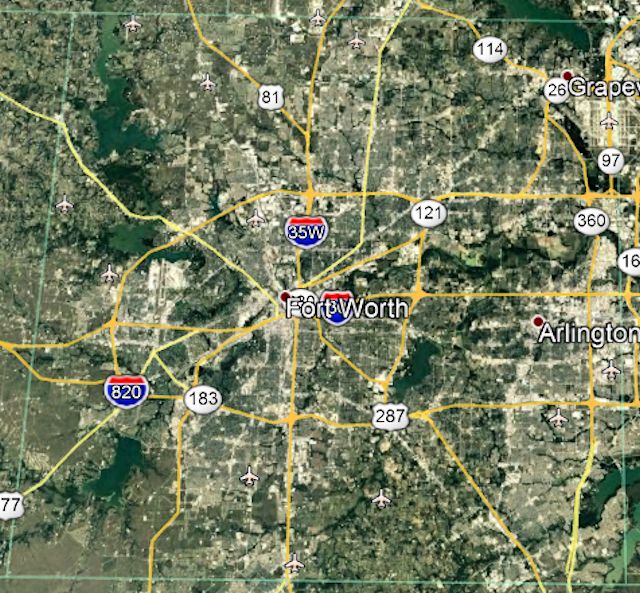

Below is a recent satellite photo of Tarrant County.

As you can see, Tarrant County today has a lot of concrete (urban areas) and water (six lakes) with a little green (rural areas) in between. The population is about two million, about 1.2 million of that in Fort Worth and Arlington.

As you can see, Tarrant County today has a lot of concrete (urban areas) and water (six lakes) with a little green (rural areas) in between. The population is about two million, about 1.2 million of that in Fort Worth and Arlington.

The 2020 census estimated that Tarrant County is 98.71 percent urban, 1.29 percent rural.

Yes, today in Tarrant County few people are far from a neighbor, a mall, or a Starbucks.

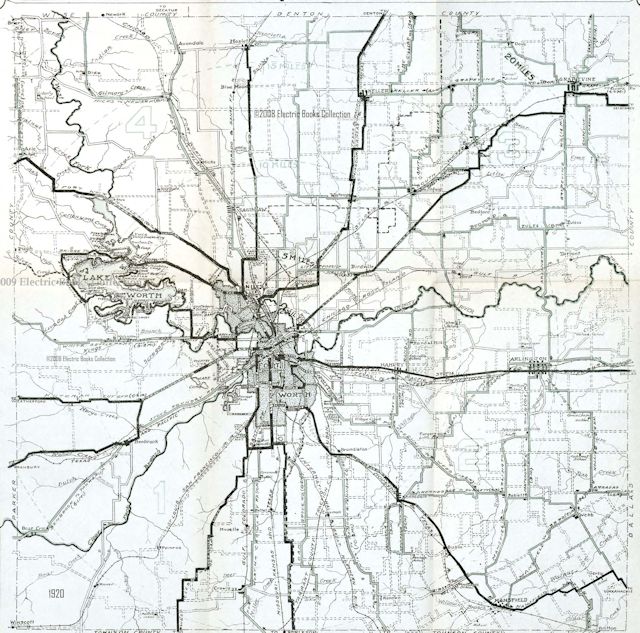

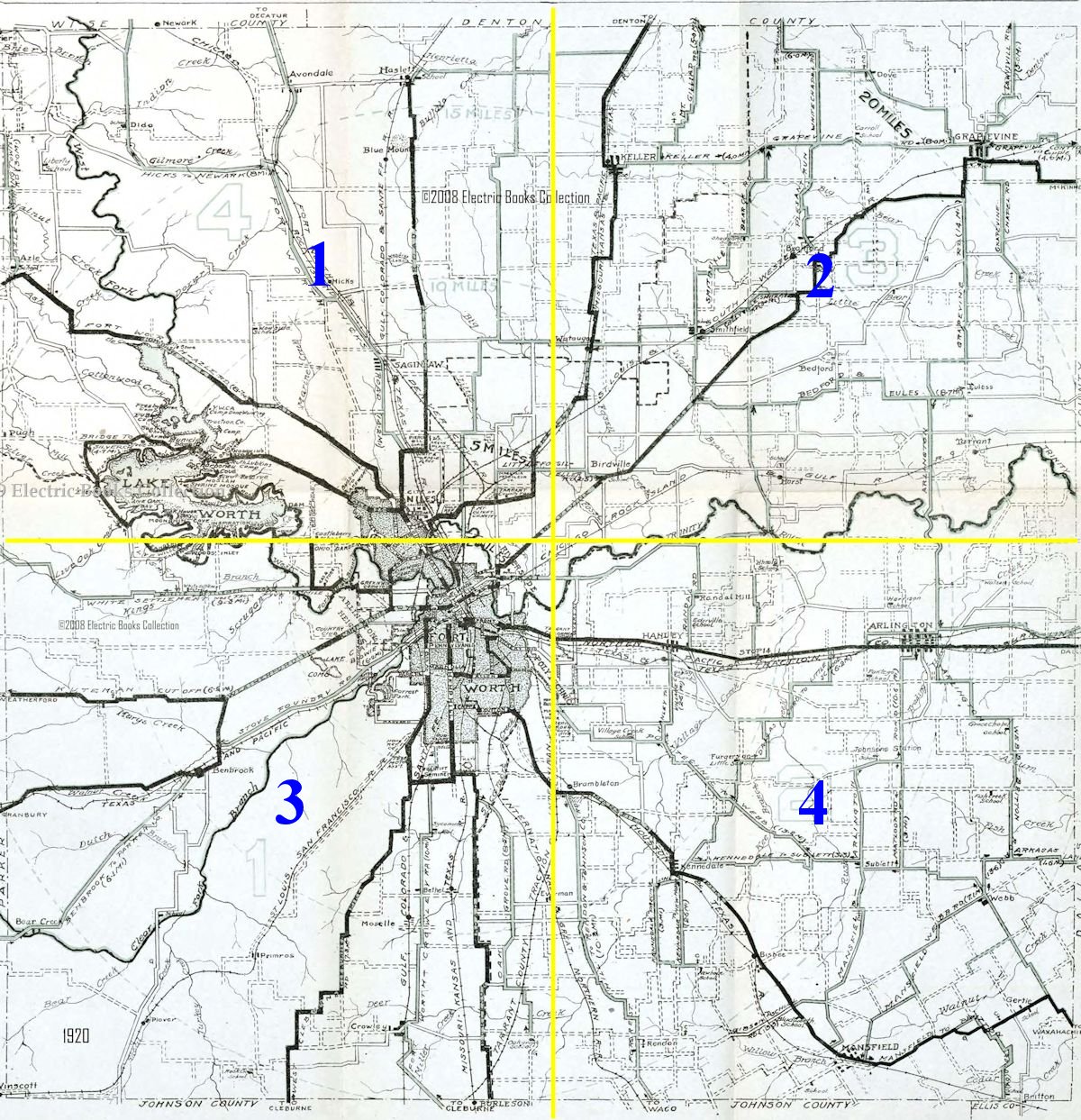

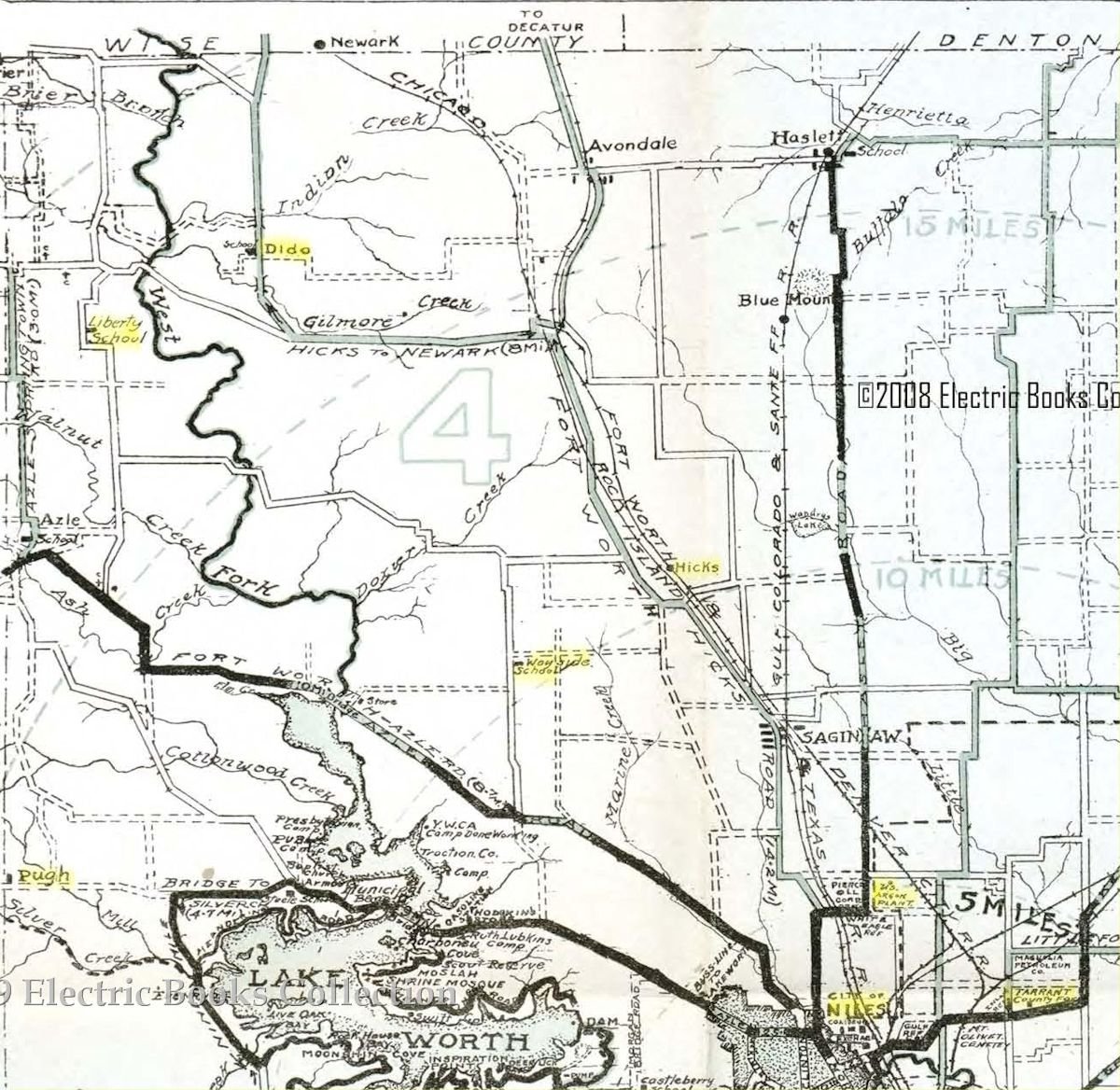

How different Tarrant County was a century ago. This map is from 1920. Outside of Fort Worth, Tarrant County was still largely rural—farmland and dusty, rutted roads more accustomed to horse and buggy than to automobile. (From Pete Charlton’s “1000+ Lost Antique Maps of Texas & the Southwest on DVD-ROM.”)

How different Tarrant County was a century ago. This map is from 1920. Outside of Fort Worth, Tarrant County was still largely rural—farmland and dusty, rutted roads more accustomed to horse and buggy than to automobile. (From Pete Charlton’s “1000+ Lost Antique Maps of Texas & the Southwest on DVD-ROM.”)

Tarrant County had only one large lake in 1920: Lake Worth.

The population of Tarrant County in 1920 was 153,000—most of that (106,000) in Fort Worth.

The 1920 map shows dozens of small towns and country schools and churches, some named after a geographic feature (Fish Creek School, Blue Mound) or a person (Minter’s Chapel, Johnson’s Station).

The map also shows long-gone businesses, government facilities, and travel routes: Texas Motor Car Association, the county poor farm, the helium plant, the interurban, the Kuteman Cutoff.

Most of the country schools and country churches disappeared years ago as the county urbanized. Most of the small towns were absorbed by other towns (Dove by Southlake, Birdville by Haltom City).

But that 1920 map has stories to tell about the Tarrant County of a century ago: the place names and the people behind those place names.

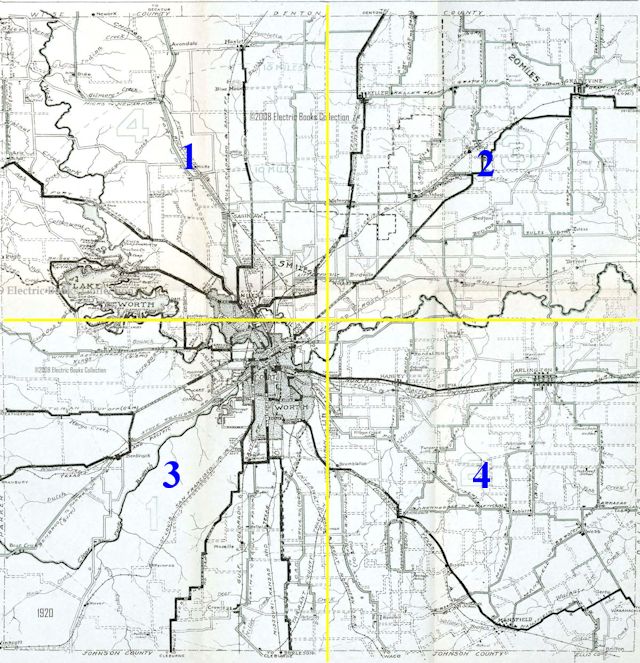

A large map with lots of tiny place name labels does not lend itself to easy reading on a small computer monitor, so I have divided the 1920 county map into quadrants. I will devote one post to each quadrant and at the bottom of each post repeat the image of that quadrant as large as possible—1,200 pixels wide. Place names with hyperlinks are treated more fully in other posts.

A large map with lots of tiny place name labels does not lend itself to easy reading on a small computer monitor, so I have divided the 1920 county map into quadrants. I will devote one post to each quadrant and at the bottom of each post repeat the image of that quadrant as large as possible—1,200 pixels wide. Place names with hyperlinks are treated more fully in other posts.

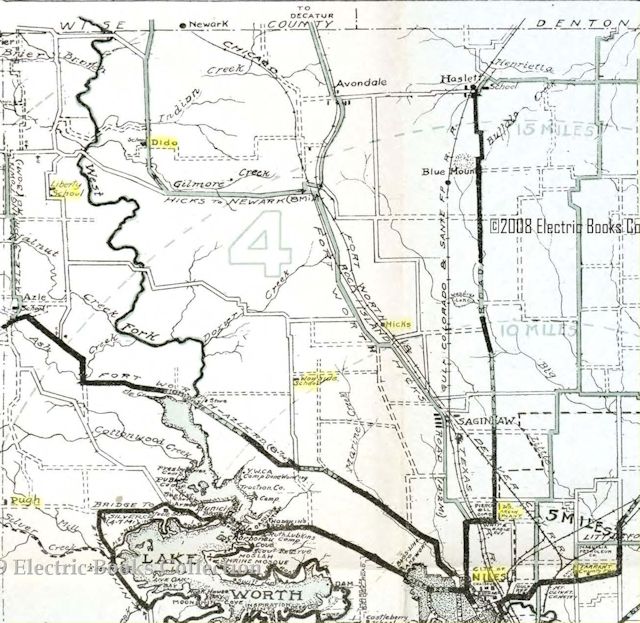

Place names in Quadrant 1, the northwest corner of the county, include the schools of Liberty and Wayside, the communities of Dido, Hicks, Pugh, and Niles City, the Tarrant County poor farm, and the helium plant.

Place names in Quadrant 1, the northwest corner of the county, include the schools of Liberty and Wayside, the communities of Dido, Hicks, Pugh, and Niles City, the Tarrant County poor farm, and the helium plant.

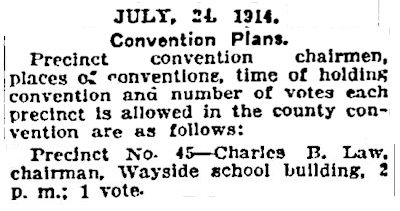

Liberty and Wayside schools were typical of country schools, which were governed by the county school board and had their own school district for tax purposes. The Wayside district was formed in 1894. County school districts sometimes consolidated. Today the Eagle Mountain-Saginaw school district has a Wayside Middle School.

Liberty and Wayside schools were typical of country schools, which were governed by the county school board and had their own school district for tax purposes. The Wayside district was formed in 1894. County school districts sometimes consolidated. Today the Eagle Mountain-Saginaw school district has a Wayside Middle School.

Then, as now, public buildings such as schoolhouses and churches were used as polling places.

School buildings in sparsely populated rural areas may have had only one room. Depending on when they were built, by 1920 such buildings might have been brick but also might have been wood frame.

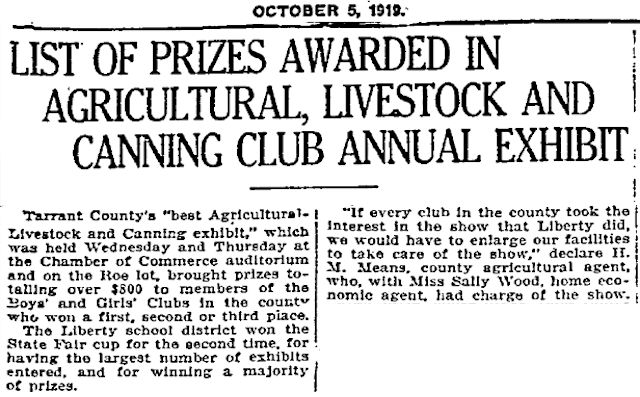

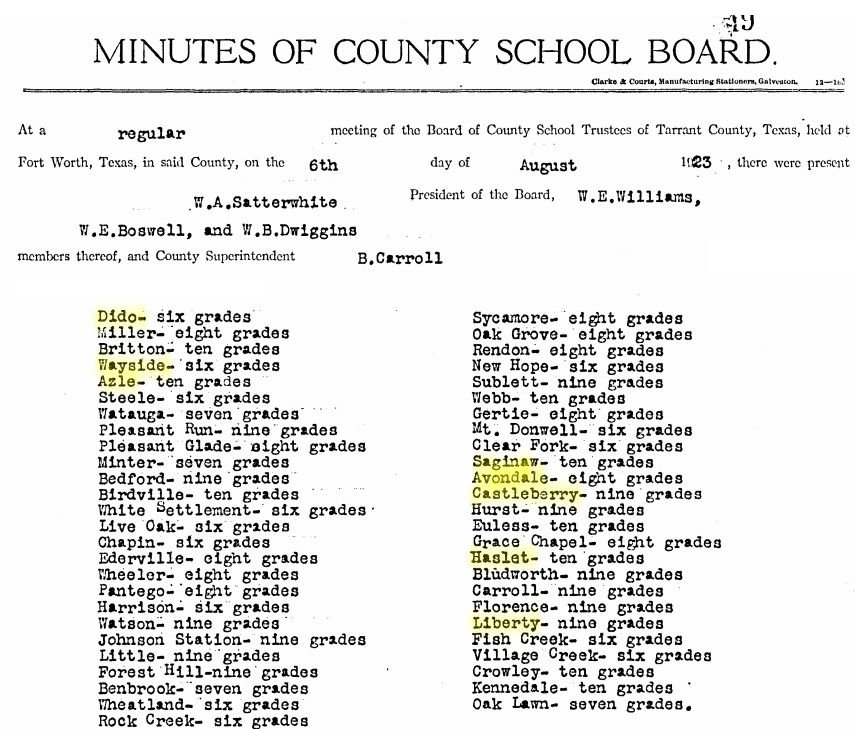

The minutes of a 1923 county school board meeting show the grades taught by each school.

The minutes of a 1923 county school board meeting show the grades taught by each school.

Two men and two communities in Quadrant 1 deserve mention.

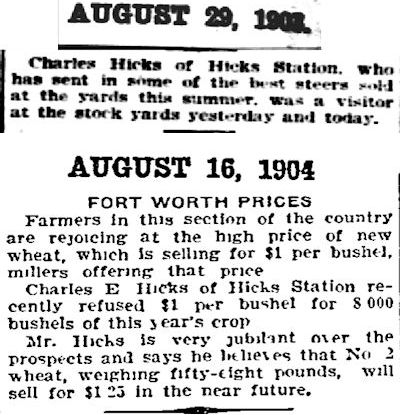

Charles Edward Hicks, born in 1857, was raised as a Quaker in Pennsylvania.

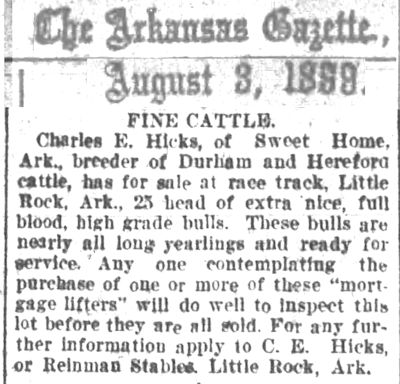

He came to Texas at age nineteen but then moved to Arkansas to plant cotton and raise cattle.

He came to Texas at age nineteen but then moved to Arkansas to plant cotton and raise cattle.

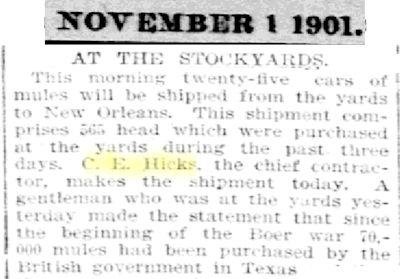

When the Boer War began in South Africa in 1899 Hicks began supplying the British with horses and mules.

In 1901, just as Fort Worth was trying to persuade Swift and Armour to build packing plants at the stockyards, Hick returned to Texas and bought six thousand acres of ranchland north of Fort Worth. He called his ranch “Hicks Meadows.”

In 1901, just as Fort Worth was trying to persuade Swift and Armour to build packing plants at the stockyards, Hick returned to Texas and bought six thousand acres of ranchland north of Fort Worth. He called his ranch “Hicks Meadows.”

There he grew wheat and raised cattle.

He also established himself at the stockyards and continued to sell horses and mules to England. O. W. Matthews, secretary of the Fort Worth Stock Yards Company, said: “Mr. Hicks sold to the British government during the Boer War more horses and mules than ever were delivered to any government up to that time. His success was due to his absolute square dealing with the government and his spirit of fairness with his dealers. As a judge of animals he has never been equaled.”

He also established himself at the stockyards and continued to sell horses and mules to England. O. W. Matthews, secretary of the Fort Worth Stock Yards Company, said: “Mr. Hicks sold to the British government during the Boer War more horses and mules than ever were delivered to any government up to that time. His success was due to his absolute square dealing with the government and his spirit of fairness with his dealers. As a judge of animals he has never been equaled.”

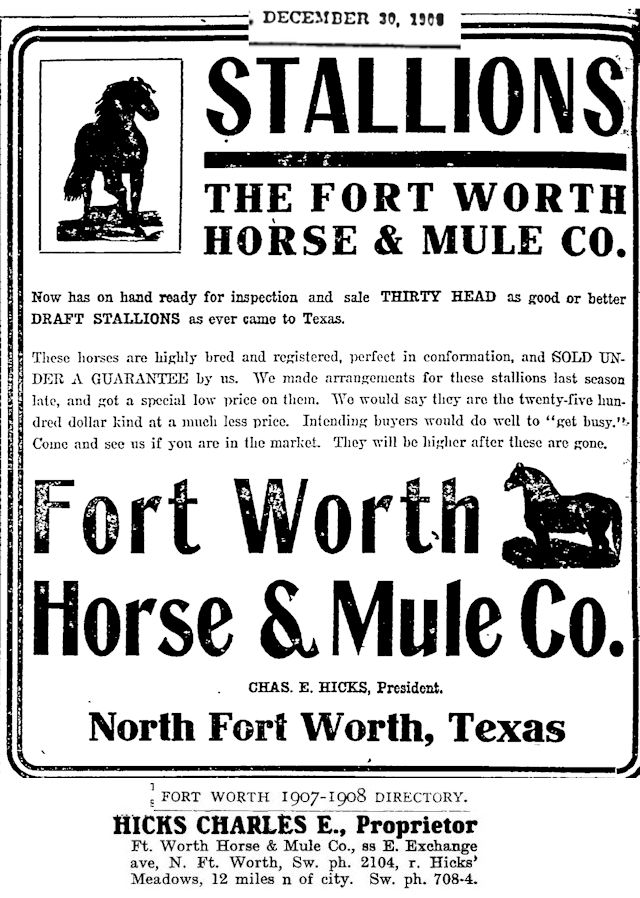

Hicks owned Fort Worth Horse and Mule Company, which was the biggest equine operator at the stockyards.

Hicks owned Fort Worth Horse and Mule Company, which was the biggest equine operator at the stockyards.

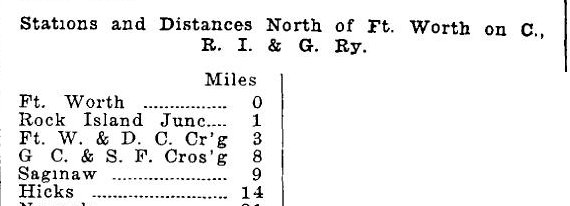

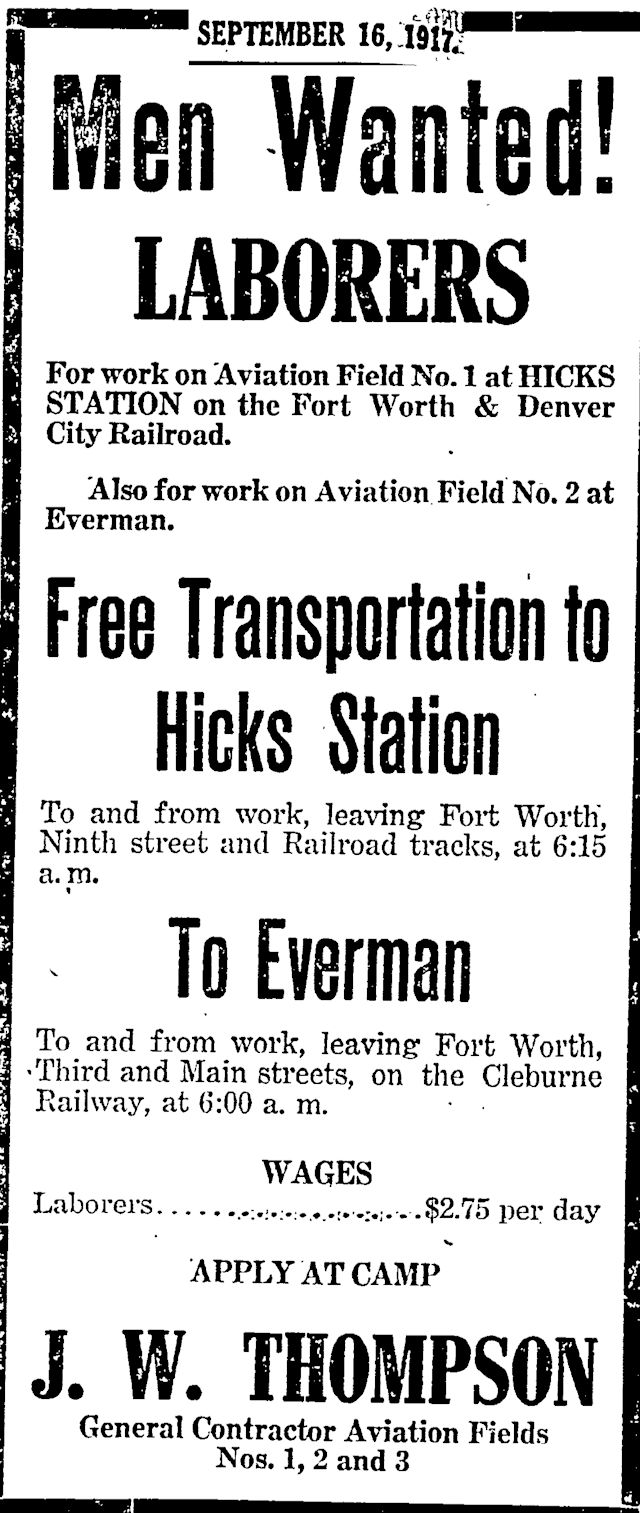

Two railroads—the Rock Island and the Fort Worth & Denver—had a station near Hicks’s ranch. The Rock Island also built stock pens at the station to ship cattle. The station was named “Hicks Station.”

Two railroads—the Rock Island and the Fort Worth & Denver—had a station near Hicks’s ranch. The Rock Island also built stock pens at the station to ship cattle. The station was named “Hicks Station.”

A community grew up around the station.

A community grew up around the station.

Fast-forward to 1917 and a new war. By now C. E. Hicks was sixty and in poor health. And by now Waddy Ross was the biggest seller of horses and mules at the stockyards, selling to the U.S. government during World War I.

Fast-forward to 1917 and a new war. By now C. E. Hicks was sixty and in poor health. And by now Waddy Ross was the biggest seller of horses and mules at the stockyards, selling to the U.S. government during World War I.

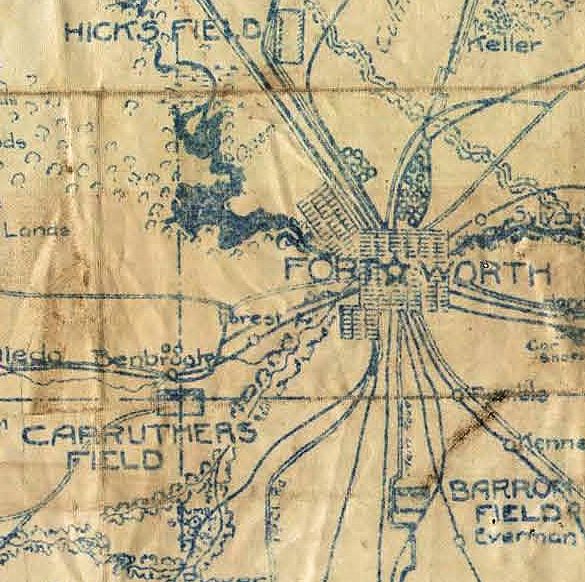

But Hicks did his part for the war effort: He let the Army build one of the three airfields of Camp Taliaferro on his ranch. The airfield was named “Hicks Field.”

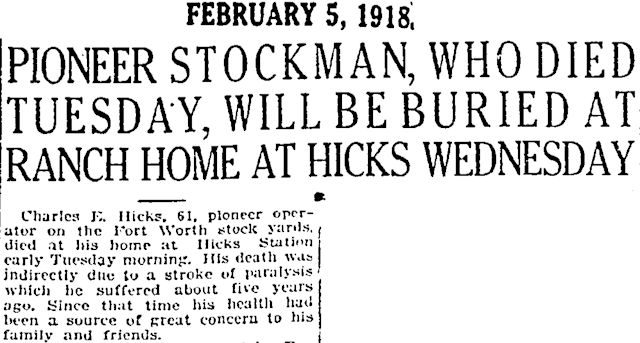

Charles Edward Hicks died at Hicks Meadows on February 5, 1918, nine months before the war ended.

Charles Edward Hicks died at Hicks Meadows on February 5, 1918, nine months before the war ended.

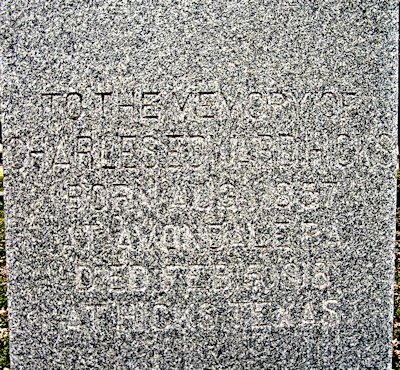

Charles Edward Hicks is buried at Dido Cemetery.

Charles Edward Hicks is buried at Dido Cemetery.

And that takes us seven miles northwest of Hicks Meadows and seventy years back in time: In 1848 settlers of Peters Colony founded the community of Dido.

As with most pioneer communities, among Dido’s first necessities were a school, a church, and a cemetery.

Dido’s school was organized in 1854, with A. C. McCanne as the first teacher. After he left to fight for the Confederacy in the Civil War his wife Margaret taught in the school.

Classes were sometimes held in the church until trustees built a schoolhouse.

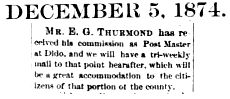

By 1874 Dido had a post office.

By 1874 Dido had a post office.

In 1887 Dempsey S. Holt donated three acres for a schoolhouse, church, and cemetery.

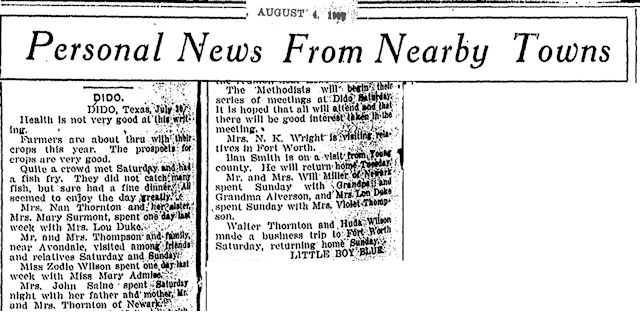

With a church, school, cemetery, and post office, Dido prospered. In 1907 the Telegram included Dido in its roundup of news from correspondents of surrounding communities. Such news was low key: how crops were doing, who was sick, who was out of town, who was in town visiting whom.

With a church, school, cemetery, and post office, Dido prospered. In 1907 the Telegram included Dido in its roundup of news from correspondents of surrounding communities. Such news was low key: how crops were doing, who was sick, who was out of town, who was in town visiting whom.

But Dido and the other communities of Quadrant 1 in 1920 are reminders that the railroads could make—or break—a town. Some towns were born because a railroad company established a station there. Other towns died because they were bypassed by a railroad or because their station closed, allowing towns that were on a railroad to drain their commerce and population.

Dido was a flourishing community until not one but two railroads—Rock Island and Fort Worth & Denver—bypassed it.

In fact, the tracks of three railroads—including the Santa Fe—were laid within three to seven miles to the east of Dido.

Avondale, Haslet, Blue Mound, Saginaw (and Newark just over the county line) were on those three railroads and survived. (Also on those railroad lines were Hicks, absorbed by Saginaw, and Niles City, absorbed by Fort Worth.)

Dido, bypassed by the railroads (and later by Highway 287) vanished.

Today the most obvious reminder of Dido is its cemetery, containing more than one thousand graves, including the unmarked graves of early settlers. The earliest marked grave is that of Amanda Thurmond (1878-1879), granddaughter of Dave Thurmond, who was one of the Dido founders.

Today the most obvious reminder of Dido is its cemetery, containing more than one thousand graves, including the unmarked graves of early settlers. The earliest marked grave is that of Amanda Thurmond (1878-1879), granddaughter of Dave Thurmond, who was one of the Dido founders.

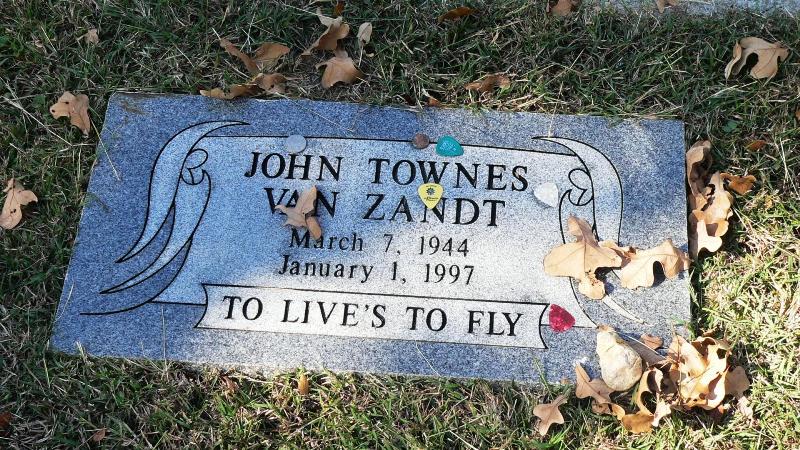

Perhaps the best-known grave is that of John Townes Van Zandt.

Perhaps the best-known grave is that of John Townes Van Zandt.

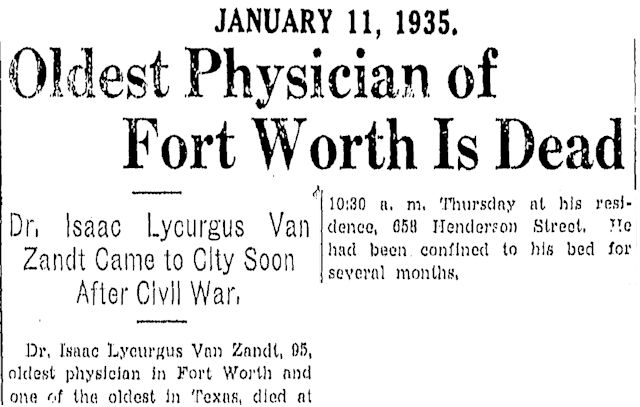

And that brings us to Dr. Isaac Lycurgus Van Zandt, the great-grandfather of Townes Van Zandt.

And that brings us to Dr. Isaac Lycurgus Van Zandt, the great-grandfather of Townes Van Zandt.

Dr. Van Zandt owned a ranch at Dido. In 1894 he donated land to expand the cemetery.

Dr. Van Zandt owned a ranch at Dido. In 1894 he donated land to expand the cemetery.

Dr. Van Zandt, the younger brother of early Fort Worth civic leader Khleber Miller Van Zandt, was born in 1840 to Isaac Van Zandt and Frances Cooke Lipscomb in the community of Elysian Fields in Harrison County (Marshall). When “Curgie” was born, even though father Van Zandt represented Harrison County in the House of Representatives of the Republic of Texas, the Van Zandts lived in a one-room log cabin.

Dr. Van Zandt, the younger brother of early Fort Worth civic leader Khleber Miller Van Zandt, was born in 1840 to Isaac Van Zandt and Frances Cooke Lipscomb in the community of Elysian Fields in Harrison County (Marshall). When “Curgie” was born, even though father Van Zandt represented Harrison County in the House of Representatives of the Republic of Texas, the Van Zandts lived in a one-room log cabin.

Khleber Van Zandt in his autobiography Force Without Fanfare recalled that when his brother was born, their father used a saw, drawknife, and some boards to make a cradle for the baby.

Khleber wrote that beds in the cabin were built in the corners, with two walls serving as headboard and one side. Strips of rawhide laced across a bed frame served as springs.

At night the family illuminated the cabin by burning pine knots, which contain pitch.

At bedtime the Van Zandts would bank the fire in the fireplace, covering hot coals with ashes to keep the coals alive. If the coals went out, the family had to borrow coals from a neighbor or start a new fire with a flintstone.

In two years the elder Van Zandt would be the Republic of Texas’s ambassador to the United States. He and his family would live in Washington as he negotiated the annexation of Texas. In Washington the Van Zandts’ next-door neighbor was John Quincy Adams. (In the Van Zandts’ new neighborhood I don’t imagine they had to go next door to borrow coals from a former president of the United States!)

Curgie, like his older brother before him, in 1857 graduated from Franklin College in Nashville. He began the study of medicine at Tulane University in New Orleans, but his education was interrupted by the Civil War. In 1861 the two brothers joined the Confederacy’s Company D, Seventh Texas Infantry.

Both brothers fought in the Battle of Fort Donelson, Tennessee and were captured on February 16, 1862 by Union soldiers and imprisoned at Camp Douglas in Chicago.

After spending more than seven months as prisoners, the brothers were released in a prisoner exchange and resumed service in the Confederate army. Curgie served as a corpsman in the Trans-Mississippi Department until the close of the war.

He then resumed his medical studies and graduated from Tulane in 1867. That year he married Ellen Henderson of Marshall. The next year Dr. Van Zandt, his wife, and his baby son—Van Zandt riding a horse laden with saddlebags, his wife and son riding in a buggy—moved to Fort Worth. One saddlebag contained Fort Worth’s first microscope.

Van Zandt was Fort Worth’s third physician. He partnered with first Dr. William Paxton Burts (Fort Worth’s second physician) and later with Dr. Elias J. Beall (Dr. Van Zandt’s sister Frances married Dr. Beall. Sister Ida married James Jones Jarvis and was the first woman trustee of TCU).

Dr. Van Zandt’s first home in Fort Worth was in the block bounded by 5th and 6th streets and Throckmorton and Taylor streets. In fact, he owned the entire block. With the help of the two brothers First Christian Church would build its new home in that block in 1878.

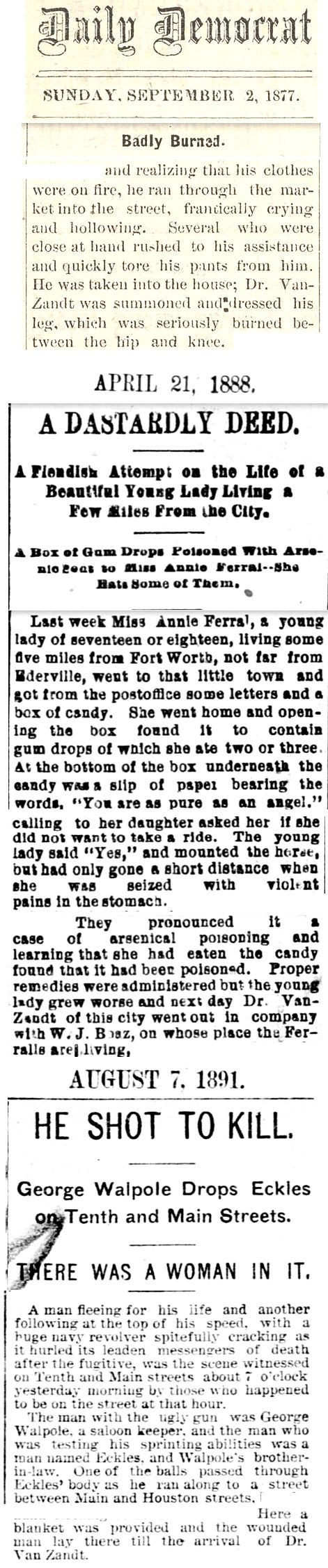

As one of the few doctors in town, Van Zandt treated a variety of injuries from burns to poisonings to gunshot wounds.

As one of the few doctors in town, Van Zandt treated a variety of injuries from burns to poisonings to gunshot wounds.

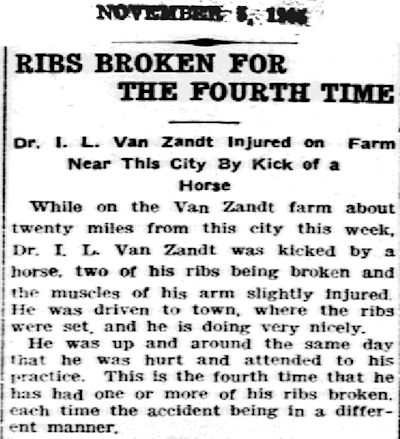

Most of the time Van Zandt did the doctoring. Sometimes he was in need of a doctor himself.

Most of the time Van Zandt did the doctoring. Sometimes he was in need of a doctor himself.

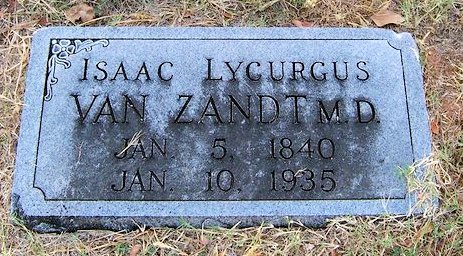

Dr. Isaac Lycurgus Van Zandt died in his home at 658 Henderson Street on the edge of Quality Hill in 1935. He was ninety-five. At the time of his death, he was the oldest physician in Fort Worth.

Dr. Isaac Lycurgus Van Zandt died in his home at 658 Henderson Street on the edge of Quality Hill in 1935. He was ninety-five. At the time of his death, he was the oldest physician in Fort Worth.

Although six Van Zandts are buried in Dido Cemetery, Dr. Van Zandt is not one of them. He is buried in the family plot in Oakwood Cemetery.

Although six Van Zandts are buried in Dido Cemetery, Dr. Van Zandt is not one of them. He is buried in the family plot in Oakwood Cemetery.

Footnote: A historical marker at Dido says the community was named for the mythological queen of Carthage. But Khleber Miller Van Zandt writes in Force Without Fanfare that in 1854 he owned a mare he had named “Dido,” which he rode from Nashville back to Marshall after college. Van Zandt family tradition is that the community of Dido was named for the horse (which may have been named for the mythical queen).

Here are the larger maps:

I am researching Dido. According to information online it was founded by David Holmes Thurmond. How does this fit with the information above?

Thank you for visiting the site. Unfortunately the author, Mike Nichols, passed away and we are working on how best to preserve this informative site.

Ooh, I love this map nerd stuff! Such fun!

I love the 1920 map and its emphasis on Azle Avenue (Nine Mile Bridge Road) and Angle Avenue (Ten Mile Bridge Road) as the roads out of town to the northwest. It’s hard to imagine Fort Worth without the Jacksboro Highway, but there it is.

Aren’t maps addictive? They show how different our little world was not so very long ago. Pete Charlton had the best collection. I could not do this blog without his legacy. Thanks.