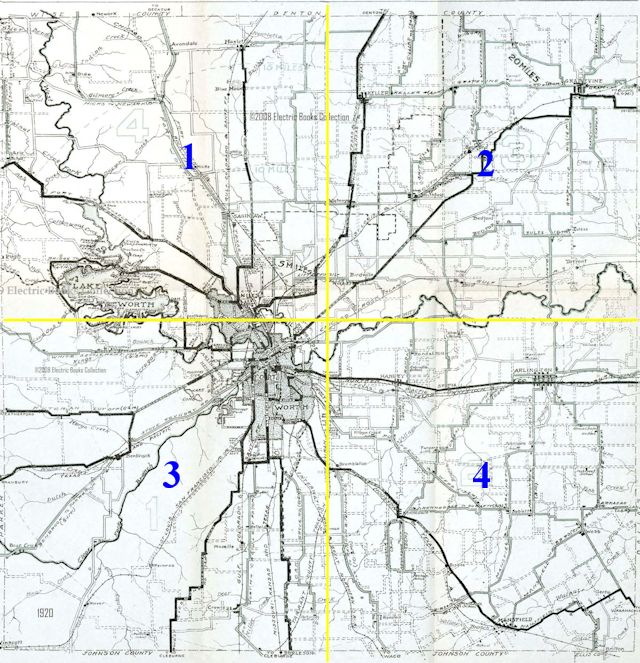

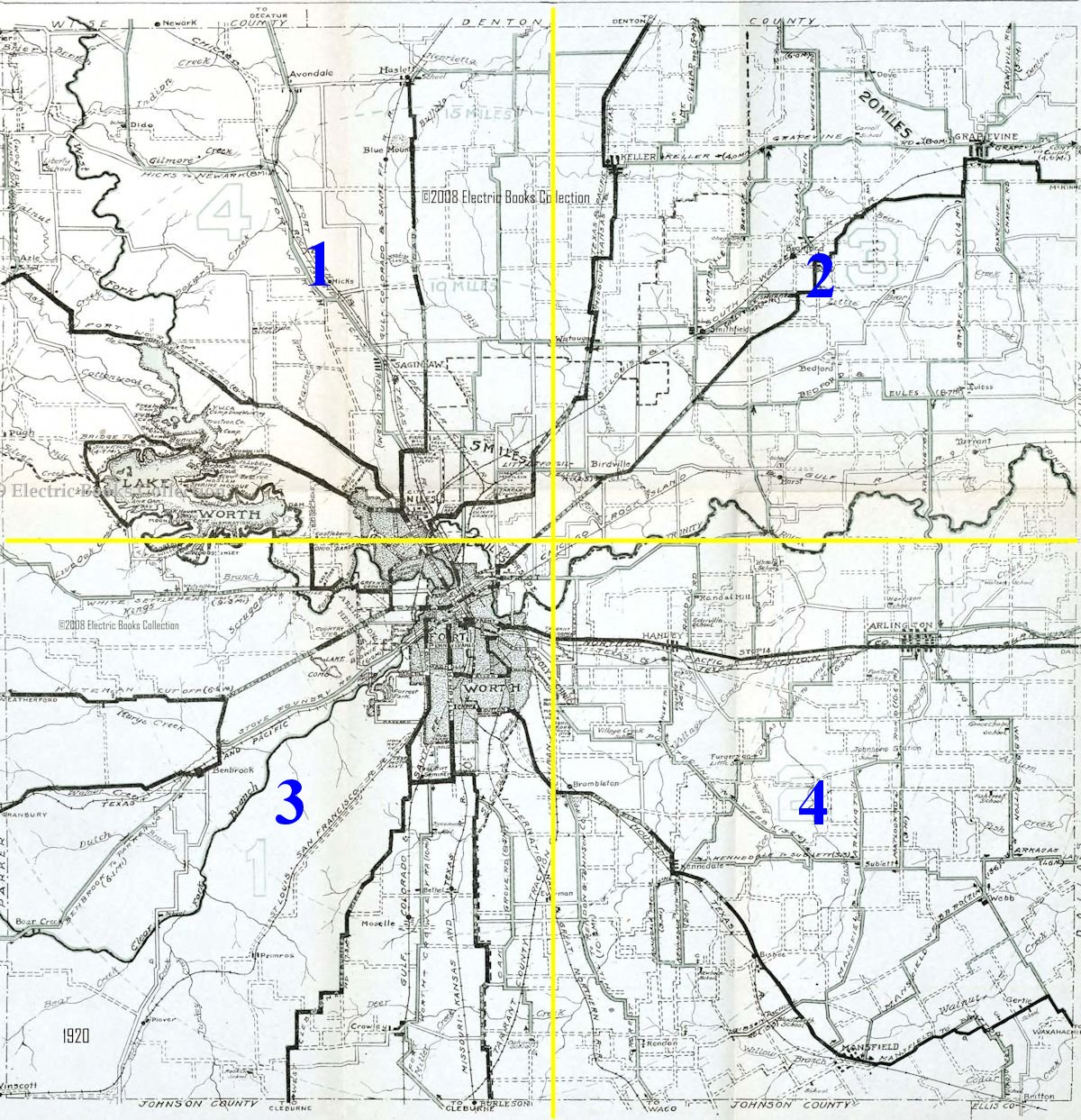

In 1920 Quadrant 4 (see Part 1) was Tarrant County’s education corner: I count fourteen schools labeled on the map.

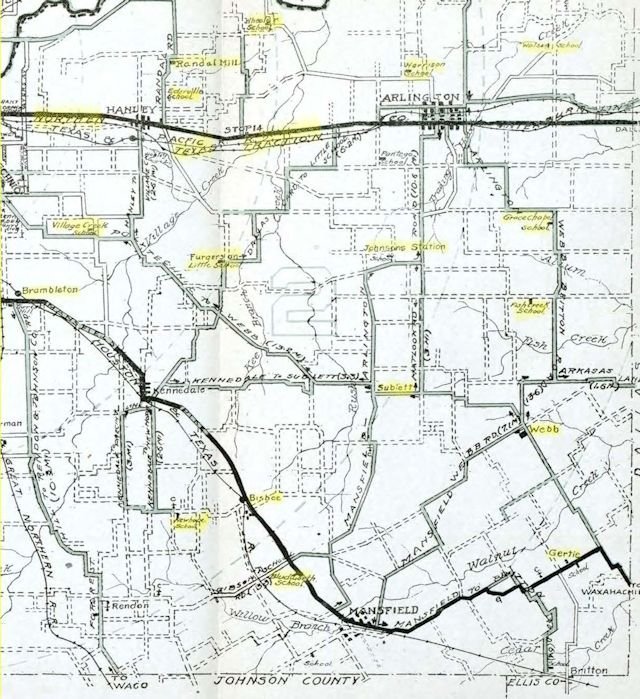

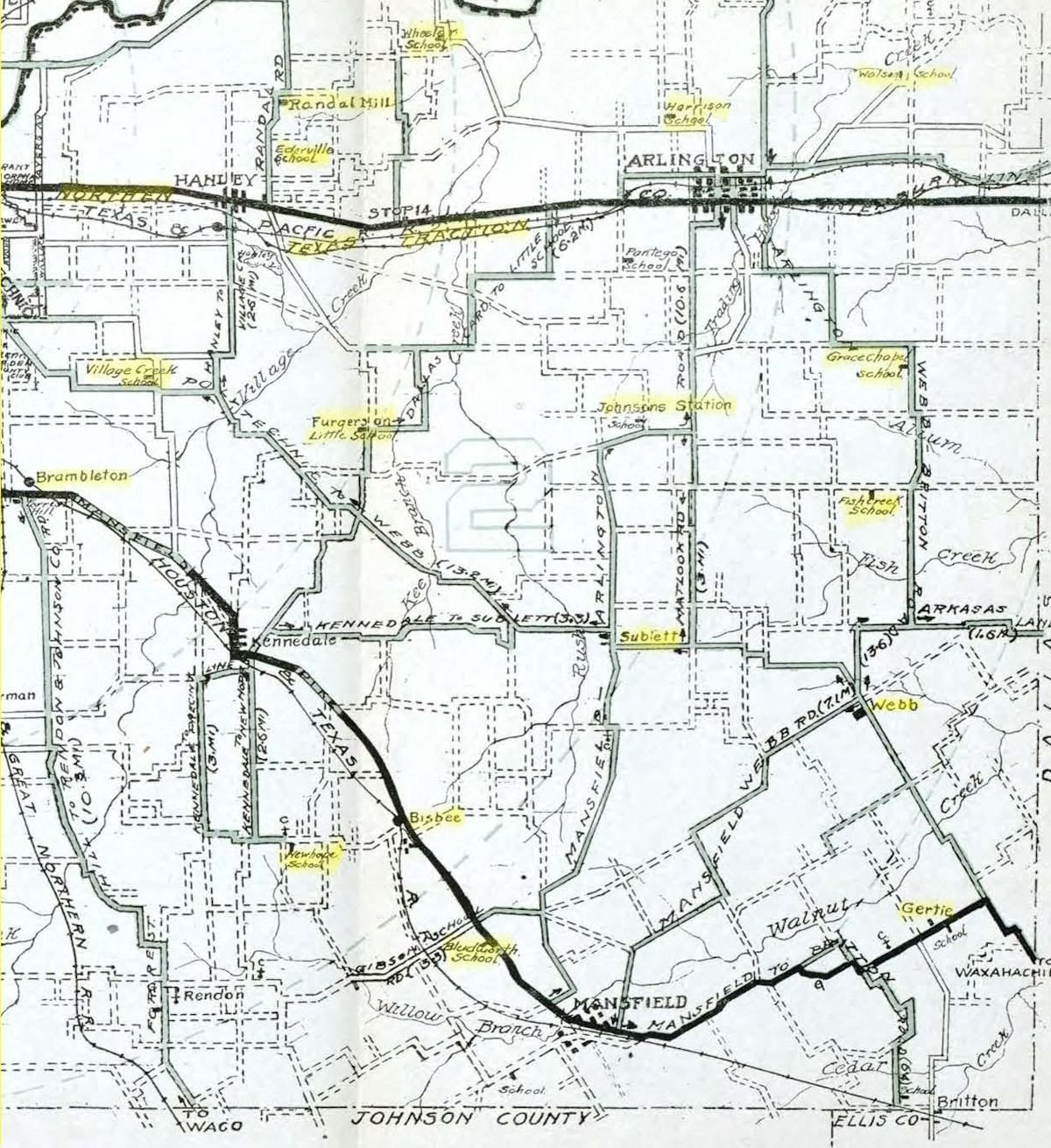

Place names in Quadrant 4 include the schools of Ederville, Wheeler, Harrison, Watson, Village Creek, Little, Fish Creek, Bludworth, Newhouse, and Grace Chapel, the communities of Johnson Station, Randol Mill, Sublett, Ferguson, Bisbee, Brambleton, Gertie, and Webb and Northern Texas Traction interurban. (See larger maps at bottom of post.) (From Pete Charlton’s “1000+ Lost Antique Maps of Texas & the Southwest on DVD-ROM.”)

Place names in Quadrant 4 include the schools of Ederville, Wheeler, Harrison, Watson, Village Creek, Little, Fish Creek, Bludworth, Newhouse, and Grace Chapel, the communities of Johnson Station, Randol Mill, Sublett, Ferguson, Bisbee, Brambleton, Gertie, and Webb and Northern Texas Traction interurban. (See larger maps at bottom of post.) (From Pete Charlton’s “1000+ Lost Antique Maps of Texas & the Southwest on DVD-ROM.”)

Well into the twentieth century the county governed rural schools, each of which had its own district. The minutes of a 1923 county school board meeting show the grades taught by each rural school. Those highlighted in yellow were in Quadrant 4.

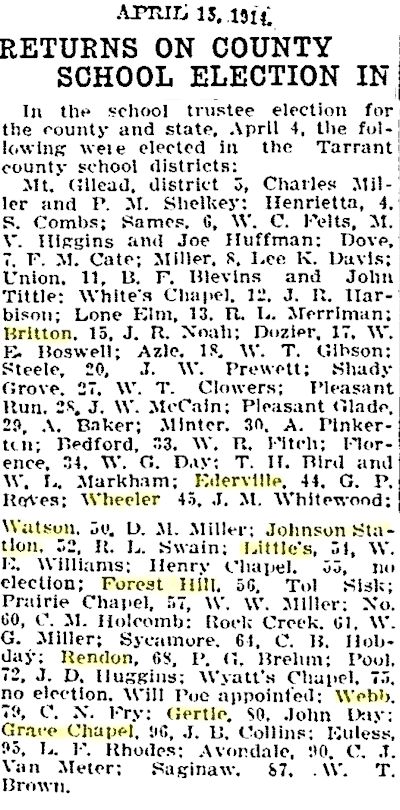

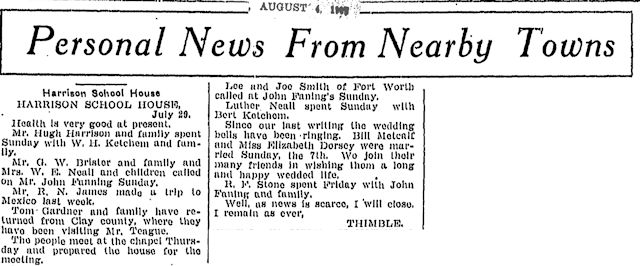

Each county school district was both named and numbered. Each district elected trustees. This news article lists the districts in Quadrant 4 in 1914.

Each county school district was both named and numbered. Each district elected trustees. This news article lists the districts in Quadrant 4 in 1914.

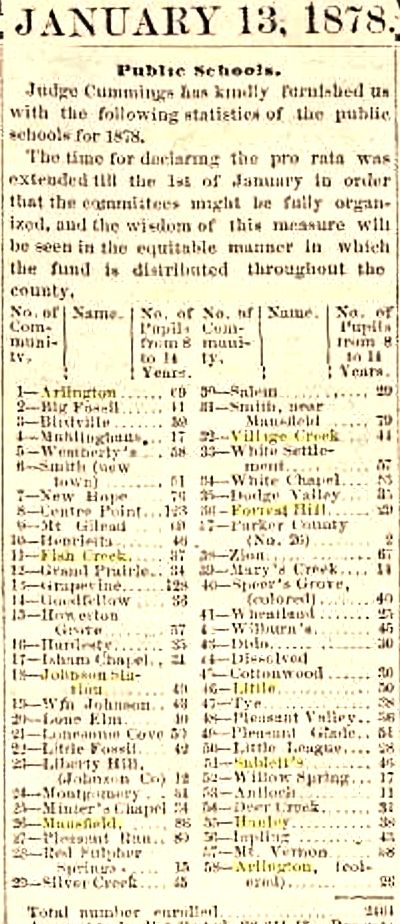

Several of the schools shown on the 1920 map already existed in 1878. The enrollment of county schools in 1878 was 2,464.

Several of the schools shown on the 1920 map already existed in 1878. The enrollment of county schools in 1878 was 2,464.

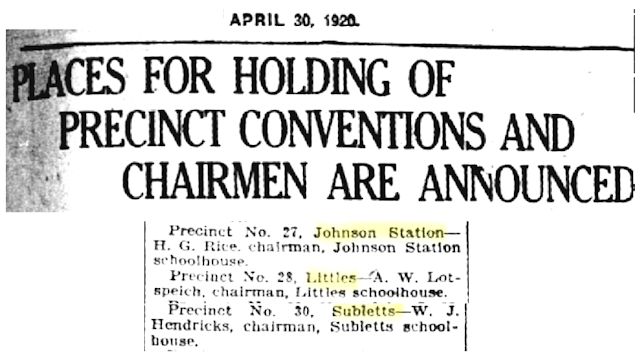

Rural schoolhouses often served as polling places and hosted precinct conventions.

Rural schoolhouses often served as polling places and hosted precinct conventions.

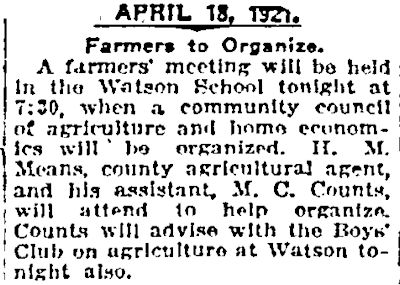

Rural schoolhouses such as the Watson School also served as auditoriums for public meetings.

Rural schoolhouses such as the Watson School also served as auditoriums for public meetings.

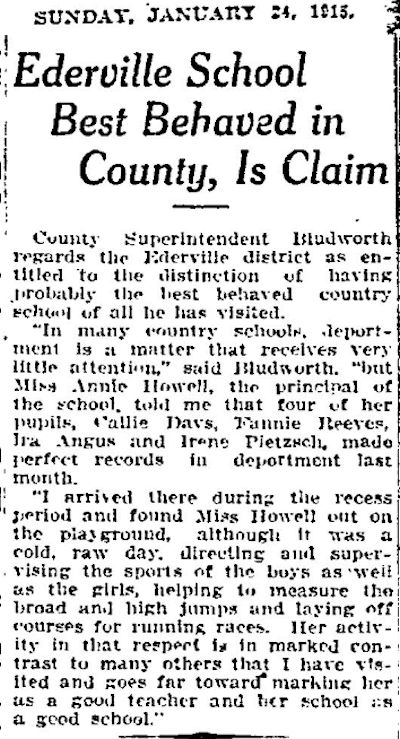

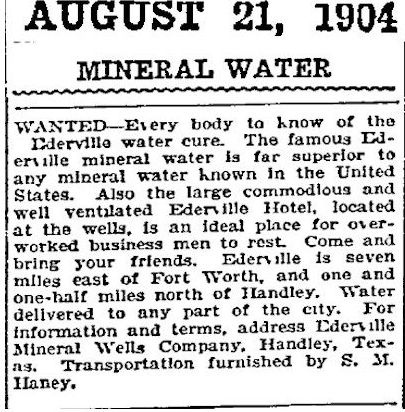

Ederville School is shown on the 1920 county map, but the community of Ederville is not. In the 1880s, after George Eder discovered that water from his wells had a health-giving mineral content, a community named “Ederville” grew up around his wells. First a hotel was built so that guests could “take the waters.” Then came a school, pavilion, skating rink, post office, blacksmith, saloon, church, and drugstore.

Ederville School is shown on the 1920 county map, but the community of Ederville is not. In the 1880s, after George Eder discovered that water from his wells had a health-giving mineral content, a community named “Ederville” grew up around his wells. First a hotel was built so that guests could “take the waters.” Then came a school, pavilion, skating rink, post office, blacksmith, saloon, church, and drugstore.

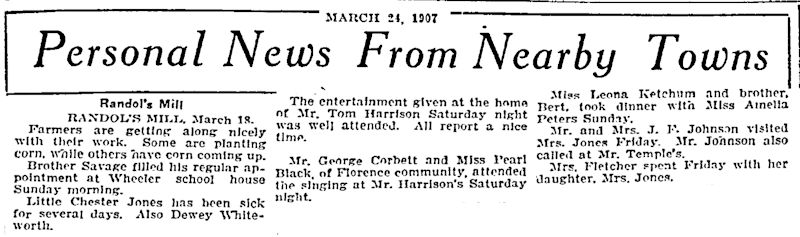

The Harrison School was located not far from Randol Mill (see below) and may have been named for the Harrison family who lived nearby. Robert A. Randol’s first wife was a Harrison, and he deeded the land for nearby Harrison Cemetery.

The Harrison School was located not far from Randol Mill (see below) and may have been named for the Harrison family who lived nearby. Robert A. Randol’s first wife was a Harrison, and he deeded the land for nearby Harrison Cemetery.

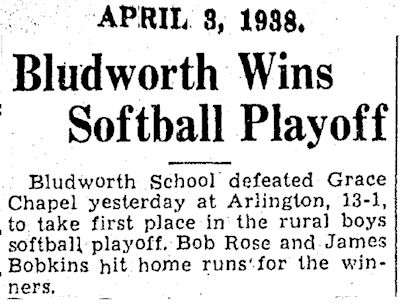

Bludworth school district was formed in 1916 by consolidating the Pool, Gibson, and Wyatt’s Chapel districts. The district and its school were named for George T. Bludworth, who was county school superintendent at the time the school was built.

Bludworth school district was formed in 1916 by consolidating the Pool, Gibson, and Wyatt’s Chapel districts. The district and its school were named for George T. Bludworth, who was county school superintendent at the time the school was built.

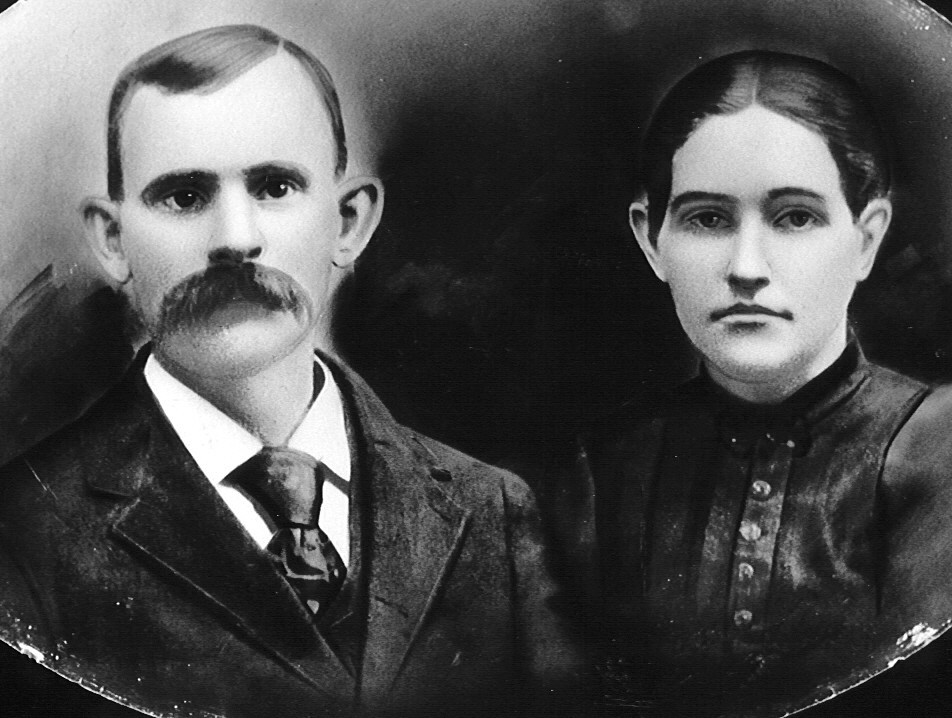

About 1847 two children—Jason Bryant Little and Rebecca Turner—migrated with their families by wagon train from east Texas to an area that two years later would become Tarrant County.

About 1847 two children—Jason Bryant Little and Rebecca Turner—migrated with their families by wagon train from east Texas to an area that two years later would become Tarrant County.

According to Little family historian Mary Fallwell Henderson, also traveling in that wagon train were Harvey and Mary Ann Turner Hawkins. Mrs. Hawkins was Rebecca’s mother.

The social circle of settlers on the frontier was small: Families migrated together, settled together, and intermarried.

So it was with Jason Bryant Little and Rebecca Turner. In a few years they married and established a homestead not far from the Hawkins homestead.

When the Civil War began Little enlisted in the Confederate army. He and Rebecca had three children five years old or younger as he left.

In 1863 Little would survive Union General Ulysses S. Grant’s siege of Vicksburg. But after one battle Little was found on the battlefield with a bullet wound in his head. As a result of the wound he would suffer from amnesia for two years.

Back in Texas Rebecca contended with Native Americans who were frequently sighted in the area. At night she barricaded herself and her children in their log cabin. She would place a can of oil close to their beds. If Native Americans attacked, she intended to set fire to the cabin, preferring to burn herself and her children to death rather than risk being captured.

According to Henderson, Rebecca also raised and sold vegetables to earn money. From the herbs she grew she prepared medicine, especially catnip, which was given to infants with colic.

Then came a scene played out many times among many families both Blue and Gray during the war:

One day as the Little children were outside their cabin, one of them saw a man walking toward them. The child ran into the cabin yelling, “Mama! Mama! There’s a man corning up the lane!”

Visitors on foot were a rarity for any little house on the prairie.

Yes, it was Jason Bryant Little returning home from the war. His children did not recognize him because they had been so young when he enlisted.

Rebecca Little herself was stunned: She had not heard from her husband in so long that she feared he was dead.

By 1878 Jason and Rebecca Little had donated a part of their homestead for a school. The school was named for Little. A Jason B. Little school still serves what today is south Arlington.

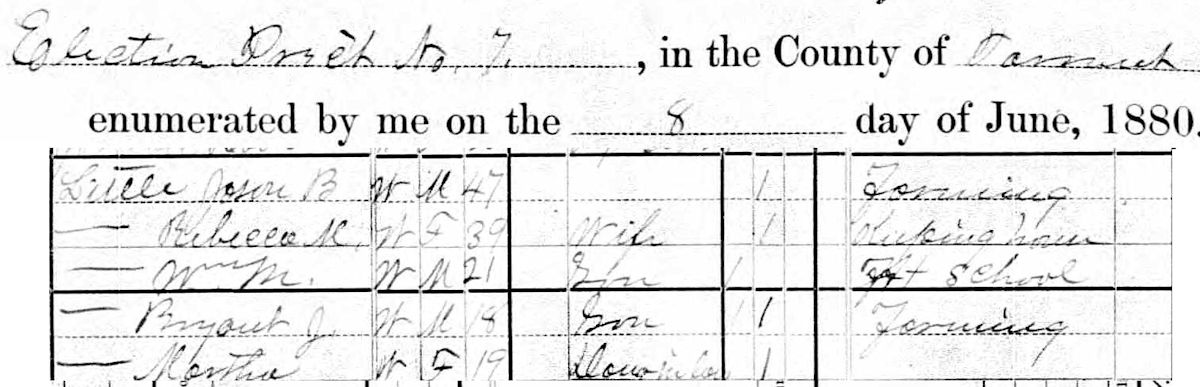

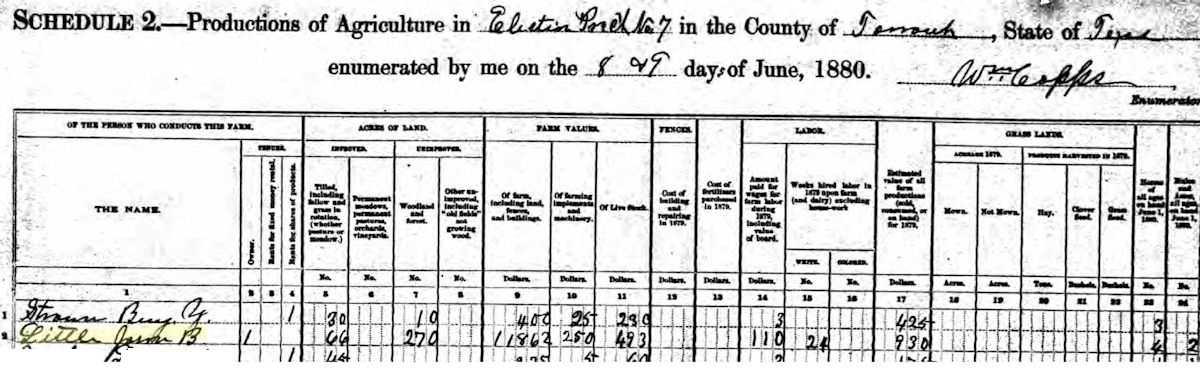

In 1880 the Littles reported sixty-six acres of field and 270 acres of woodland.

In 1880 the Littles reported sixty-six acres of field and 270 acres of woodland.

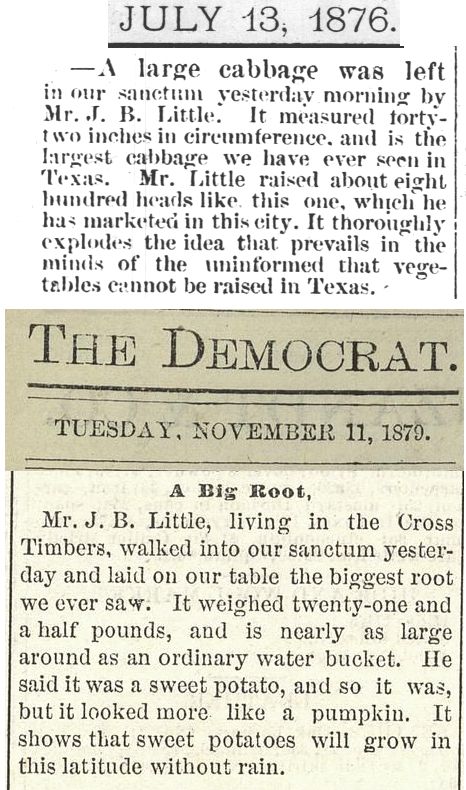

Rebecca was not the only Little with a green thumb.

Rebecca was not the only Little with a green thumb.

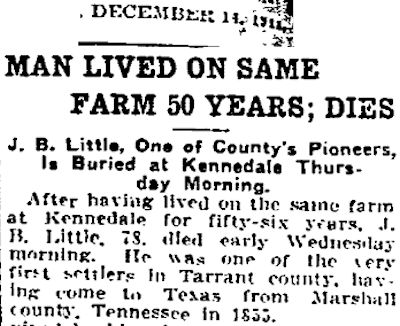

Jason Bryant Little died in 1911. Rebecca died in 1919.

Jason Bryant Little died in 1911. Rebecca died in 1919.

Pioneer families who migrated together, settled together, and married each other often were buried together. And so it was with the Littles and the Hawkinses: They are buried in Hawkins Cemetery about one mile south of the Little farm.

Pioneer families who migrated together, settled together, and married each other often were buried together. And so it was with the Littles and the Hawkinses: They are buried in Hawkins Cemetery about one mile south of the Little farm.

In 1876 Robert Andrew Randol bought the water mill that had been built in 1856 by Archibald Franklin Leonard on the Trinity River east of Fort Worth. A community, with a school, grew up around the mill.

In 1876 Robert Andrew Randol bought the water mill that had been built in 1856 by Archibald Franklin Leonard on the Trinity River east of Fort Worth. A community, with a school, grew up around the mill.

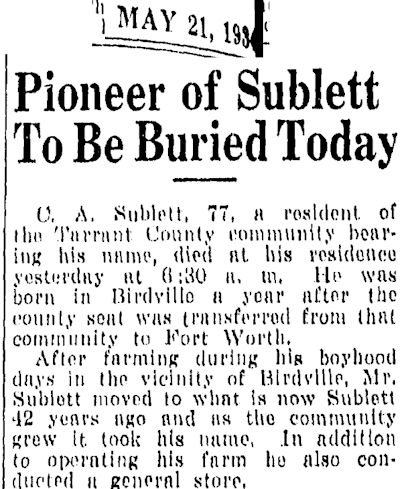

Ten miles south of Randol Mill, by 1878 there also was a school at the community of Sublett, which had grown up around the general store of Charles A. Sublett. The store also served as the Sublett post office, with Charles Sublett as postmaster. The post office received mail from Johnson Station. The Sublett postman delivered mail on horseback.

Ten miles south of Randol Mill, by 1878 there also was a school at the community of Sublett, which had grown up around the general store of Charles A. Sublett. The store also served as the Sublett post office, with Charles Sublett as postmaster. The post office received mail from Johnson Station. The Sublett postman delivered mail on horseback.

Today many residents of Sublett are buried in nearby Rehoboth Cemetery.

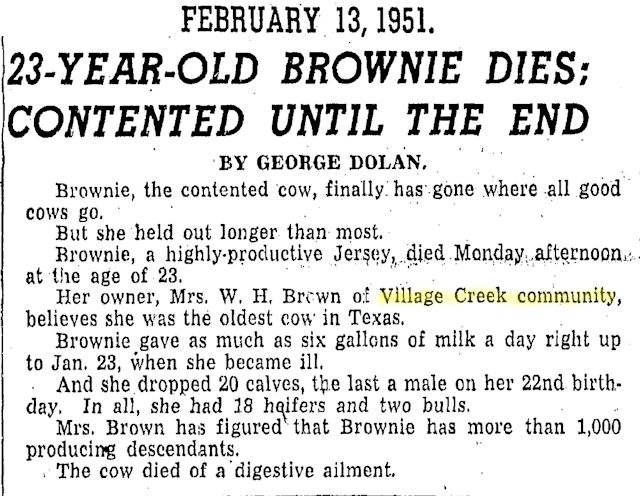

The community of Village Creek also had a school by 1878. Even in 1951, with Fort Worth’s city limits creeping ever closer, Village Creek was a “community.” Note the George Dolan byline.

The community of Village Creek also had a school by 1878. Even in 1951, with Fort Worth’s city limits creeping ever closer, Village Creek was a “community.” Note the George Dolan byline.

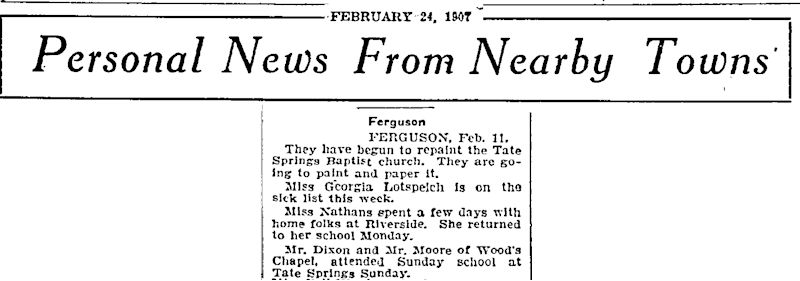

The community of Ferguson, with the homes of L., D., and J. P. Ferguson nearby, appears on an 1895 map.

The community of Ferguson, with the homes of L., D., and J. P. Ferguson nearby, appears on an 1895 map.

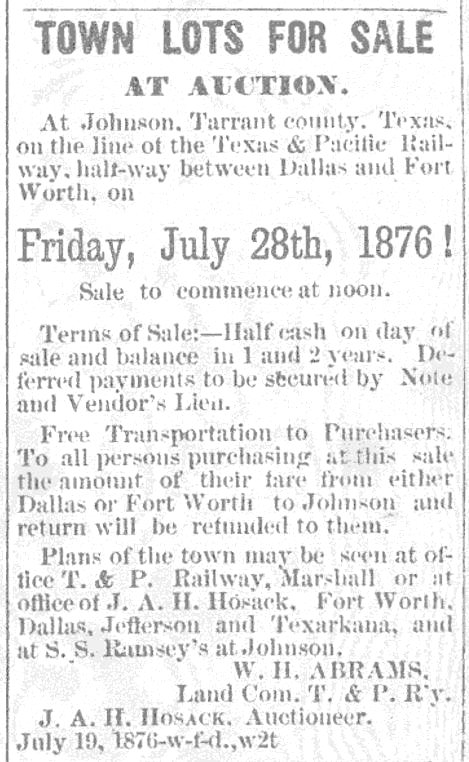

Johnson Station, of course, was named for the ubiquitous Middleton Tate Johnson. The community had a mill, school, post office, and cemetery. Today the area is in south Arlington.

Johnson Station, of course, was named for the ubiquitous Middleton Tate Johnson. The community had a mill, school, post office, and cemetery. Today the area is in south Arlington.

The community of Gertie had a church and a school. Its school district operated until at least 1943.

The community of Gertie had a church and a school. Its school district operated until at least 1943.

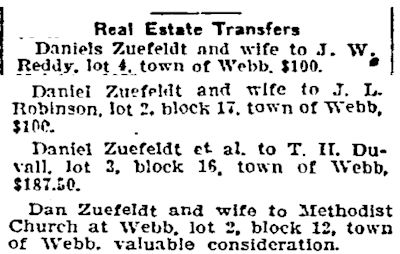

Just north of Gertie in the early 1880s Canadian-born Daniel Zuefeldt opened a general store.

Just north of Gertie in the early 1880s Canadian-born Daniel Zuefeldt opened a general store.

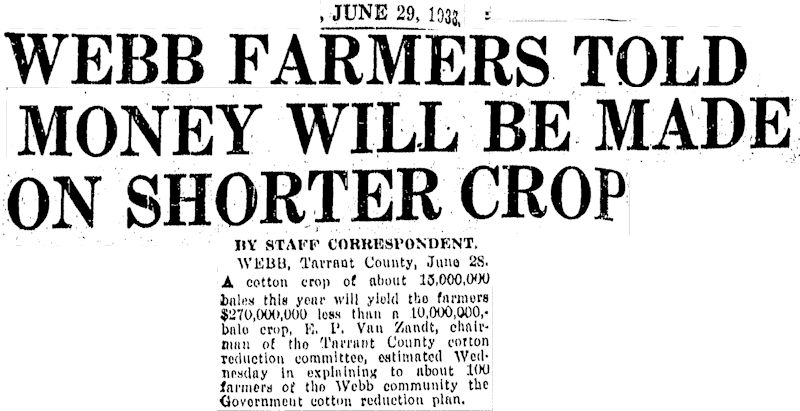

A community grew up around the store. Zuefeldt provided much of the land for that town. According to the Texas State Historical Association, the town originally was named “Bowman Spring” for a family who had settled in the area in 1852. The town was renamed “Webb” about 1895. Between 1895 and 1901 Webb had a post office, and in 1897 it had two churches. By 1976 Webb had a church, a school, a factory, and at least one other business. But in 1965 the Webb school district was absorbed by the Mansfield school district, and by 1987 Webb had fewer than fifty residents. The community is now part of Arlington.

Webb, like most of the vanished communities on the 1920 county map, was an agricultural community—farming, ranching. Social life revolved around the church and the feedstore.

Webb, like most of the vanished communities on the 1920 county map, was an agricultural community—farming, ranching. Social life revolved around the church and the feedstore.

The economy of Quadrant 4 was built on agriculture, but the railroads contributed. Handley and Arlington were located on the Texas & Pacific, and Brambleton, Kennedale, Bisbee, and Mansfield were located on the Fort Worth & New Orleans (later Houston & Texas Central).

The economy of Quadrant 4 was built on agriculture, but the railroads contributed. Handley and Arlington were located on the Texas & Pacific, and Brambleton, Kennedale, Bisbee, and Mansfield were located on the Fort Worth & New Orleans (later Houston & Texas Central).

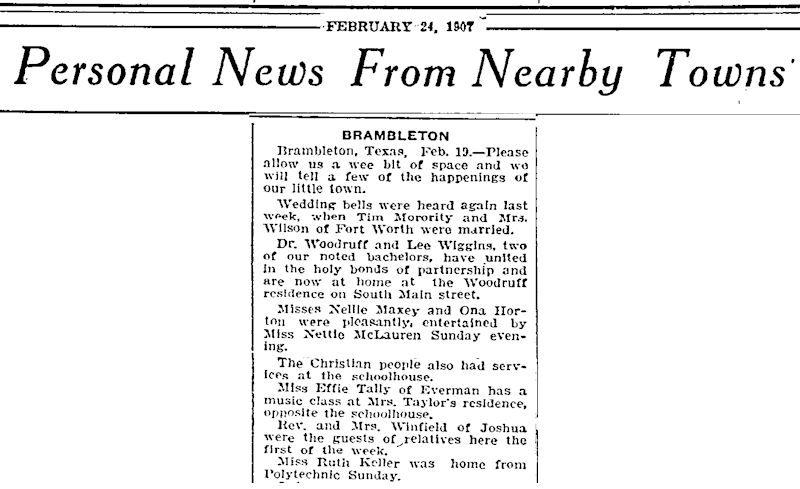

The FW&NO built its Brambleton station so close to the community of Forest Hill that the area came to be called “Brambleton.” The post office was named “Brambleton.”

The FW&NO built its Brambleton station so close to the community of Forest Hill that the area came to be called “Brambleton.” The post office was named “Brambleton.”

But Forest Hill had been around a long time—since approximately 1860, according to the city’s website. It began as a farming community and got a boost in 1886 when the FW&NO railroad built the station there.

When residents of Brambleton voted to incorporate in 1946, they reverted to the original name: “Forest Hill Village.” Three years later the name was changed to “City of Forest Hill.”

Bisbee, like Brambleton, was a community on the Fort Worth & New Orleans railroad. Bisbee, also located on the Mansfield Pike, had a gin and a brick plant.

Bisbee, like Brambleton, was a community on the Fort Worth & New Orleans railroad. Bisbee, also located on the Mansfield Pike, had a gin and a brick plant.

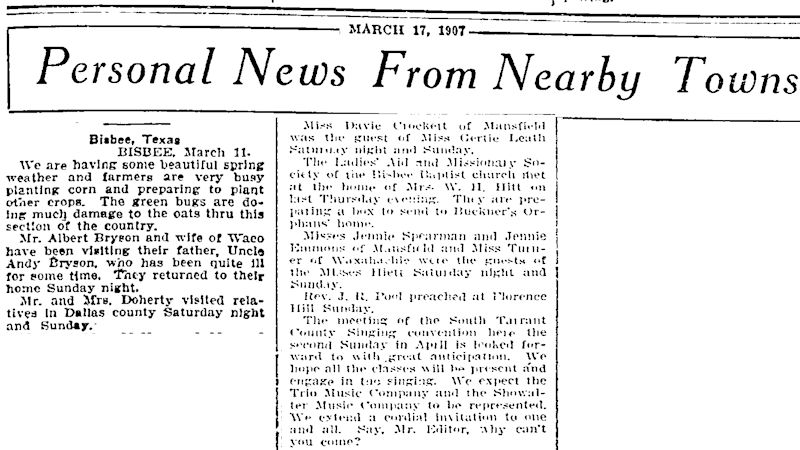

The report from the Bisbee correspondent in the Telegram’s roundup of news from nearby towns reflected the pace and priorities of rural life: how the crops were doing, who had visited whom where, who was feeling poorly.

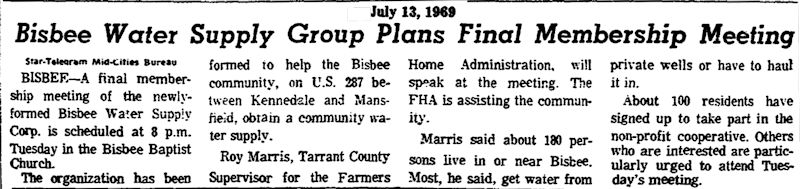

In 1969 Bisbee was still a separate community, albeit a separate community in search of a water supply.

In 1969 Bisbee was still a separate community, albeit a separate community in search of a water supply.

Bisbee was eventually absorbed by Mansfield.

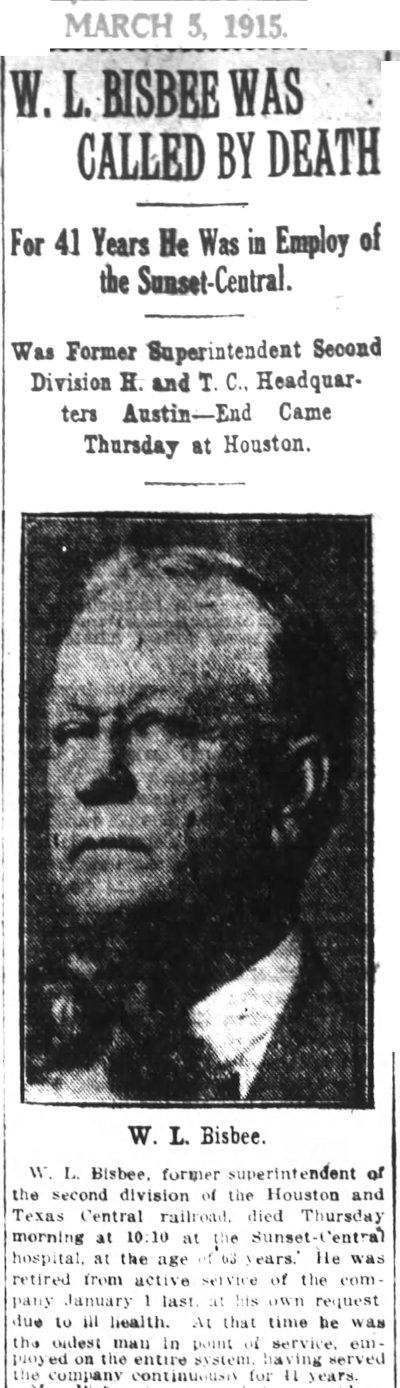

I can find no explanation of the origin of the town’s name. Personal theory: Bisbee may have been named—or renamed—for W. L. Bisbee, who worked for the FW&NO railroad for forty-two years and retired as superintendent of the division that included Tarrant County.

I can find no explanation of the origin of the town’s name. Personal theory: Bisbee may have been named—or renamed—for W. L. Bisbee, who worked for the FW&NO railroad for forty-two years and retired as superintendent of the division that included Tarrant County.

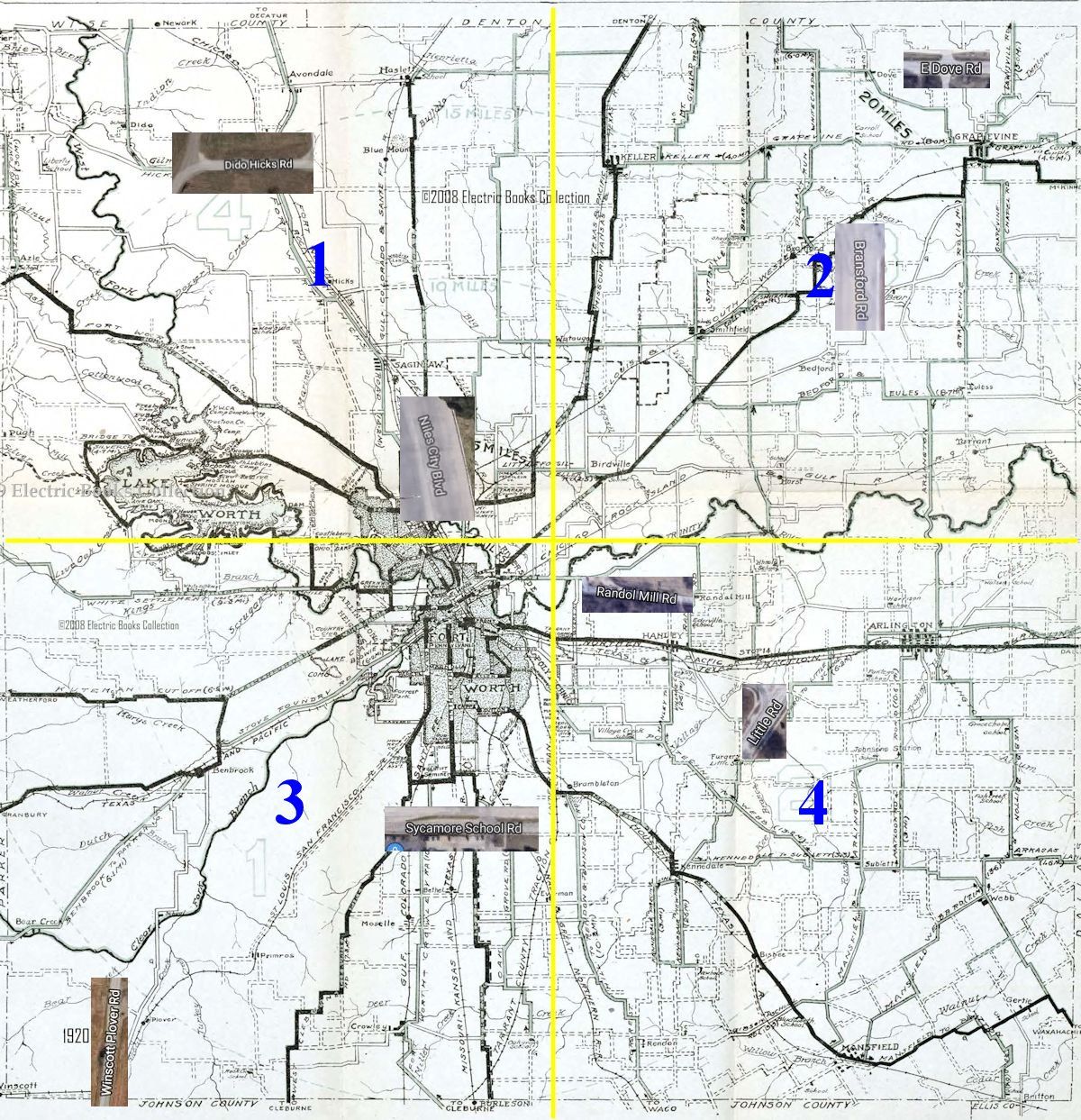

Today the names of roads in each quadrant on the map of 1920 are among the few reminders of the Tarrant County of a century ago.

Today the names of roads in each quadrant on the map of 1920 are among the few reminders of the Tarrant County of a century ago.

(Thanks to Mary Fallwell Henderson for her help.)

Do you know anything about the Wheeler school which appears to be north of Randol Mill.