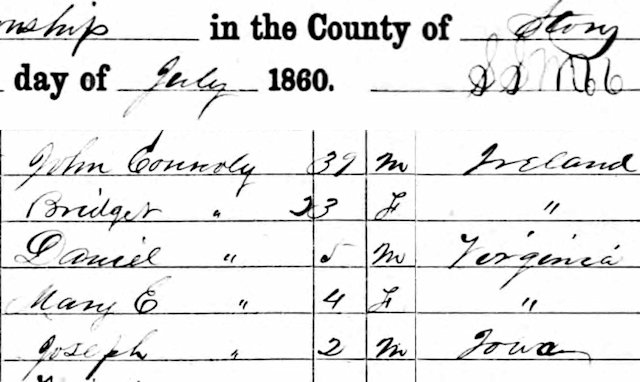

Joseph S. Connolly was born in Iowa in 1859.

His parents, John and Bridget, were Irish immigrants.

His parents, John and Bridget, were Irish immigrants.

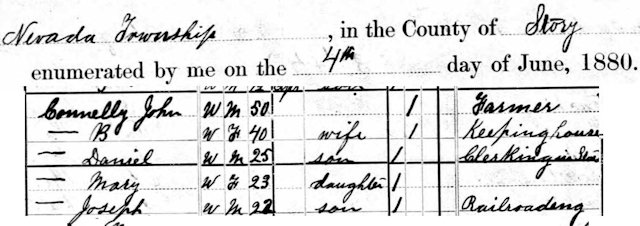

By the time Connolly was one year old Iowa had only six hundred miles of railroad track. By the time he was twenty-one, railroads were connecting America like an iron internet, creating cities and jobs, providing mass transit from coast to coast. Like many young men, Connolly was drawn to the new technology. In 1880 he was still living on his parents’ farm outside Nevada township but listed his occupation as “railroading.”

By the time Connolly was one year old Iowa had only six hundred miles of railroad track. By the time he was twenty-one, railroads were connecting America like an iron internet, creating cities and jobs, providing mass transit from coast to coast. Like many young men, Connolly was drawn to the new technology. In 1880 he was still living on his parents’ farm outside Nevada township but listed his occupation as “railroading.”

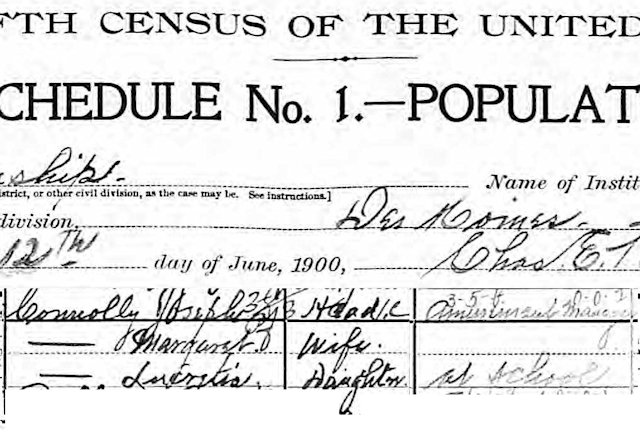

But by 1887 Connolly was living in Des Moines, where he traded the fire box for the box office: He had become a theatrical manager.

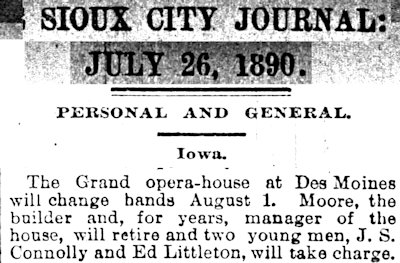

In 1890 he became co-manager of the Des Moines opera house.

In 1890 he became co-manager of the Des Moines opera house.

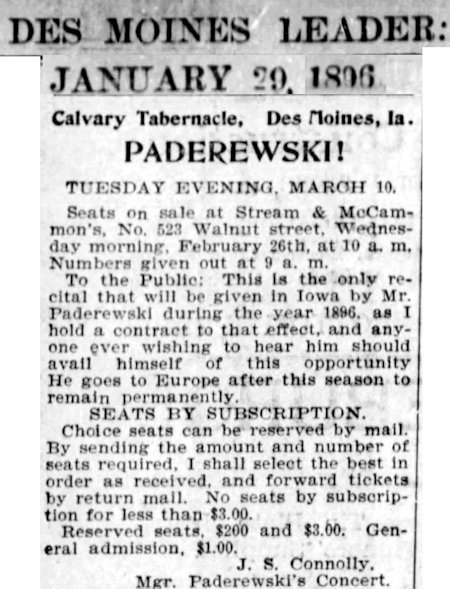

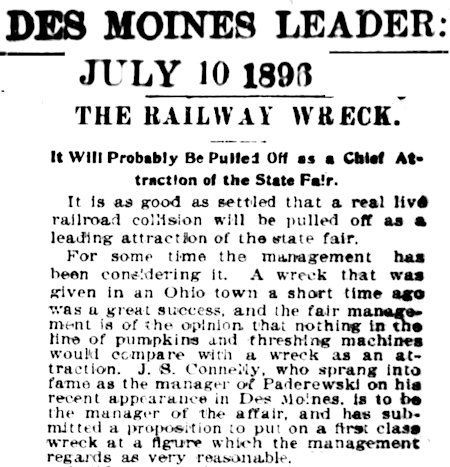

In early 1896 he managed the appearance of pianist Ignacy Paderewski in Des Moines.

In early 1896 he managed the appearance of pianist Ignacy Paderewski in Des Moines.

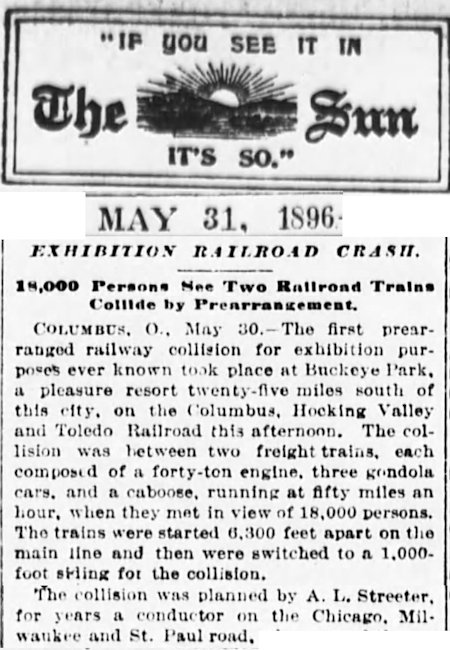

Fast-forward eleven weeks. After Paderewski wowed ’em at the Calvary Tabernacle in Des Moines, A. L. Streeter wowed ’em at Buckeye Park outside Columbus, Ohio with a different kind of crescendo.

Fast-forward eleven weeks. After Paderewski wowed ’em at the Calvary Tabernacle in Des Moines, A. L. Streeter wowed ’em at Buckeye Park outside Columbus, Ohio with a different kind of crescendo.

On May 30, 1896 Streeter, himself a former railroad man, staged an ironclad catastrophe: the head-on collision of two forty-ton steam locomotives.

The two locomotives faced each other at opposite ends of a temporary track. At a signal, an engineer at the controls of each locomotive opened the throttle. Each locomotive pulled coal tenders and a caboose as it roared down the track toward the other locomotive. One locomotive was labeled “A. L. Streeter,” the other was labeled “W. H. Fisher” (an official of the Columbus, Hocking & Toledo railroad, which supplied the locomotives).

As the locomotives neared forty miles an hour the two engineers bailed out.

Upon impact both locomotives were demolished as iron shrapnel flew in all directions from a thundercloud of steam and smoke.

Public reaction to Streeter’s spectacle ranged from adrenaline-drenched approval to stern condemnation. Preachers denounced the spectacle of “doubtful propriety and morality.” Other people defended the spectacle as “educational.”

But the true gauge of the vox populi was the “gate” that day at Buckeye Park: Twenty-five thousand people had paid perfectly good money to watch two perfectly good locomotives reduced to scrap iron.

A. L. Streeter had given the people what they wanted. And what they wanted, it seems, was controlled catastrophe.

In 1896 locomotives were billowing, belching metaphors for America’s might as an industrialized nation. Locomotives were the most powerful, fastest things on Earth. They also were physically intimidating. There was something delightfully decadent if not downright dangerous about witnessing two such behemoths butt heads like rams on rails.

Six hundred miles to the west of Columbus, Ohio, Joseph Connolly and officials of the Iowa State Fair read the “reviews” of Streeter’s spectacle. Connolly coupled his future to the new form of diversion: He combined his former job—railroading—with his current job—theatrical management.

Six hundred miles to the west of Columbus, Ohio, Joseph Connolly and officials of the Iowa State Fair read the “reviews” of Streeter’s spectacle. Connolly coupled his future to the new form of diversion: He combined his former job—railroading—with his current job—theatrical management.

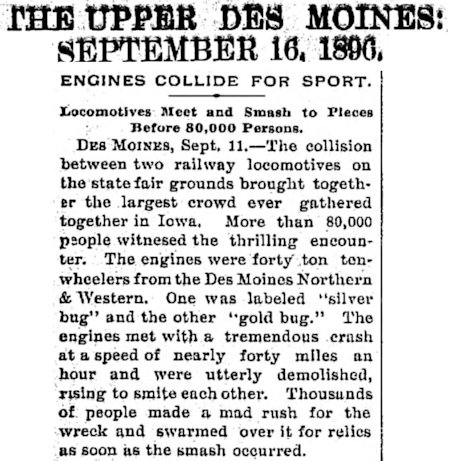

Three months after A. L. Streeter’s collision, Connolly staged his first collision at the fair in Des Moines.

Three months after A. L. Streeter’s collision, Connolly staged his first collision at the fair in Des Moines.

On September 11 two “forty-ton ten-wheelers” from the Des Moines Northern & Western railroad faced each other from opposite ends of a track. One locomotive was labeled “Gold Bug,” the other was labeled “Silver Bug,” reflecting the public debate over which metal should be the nation’s monetary standard.

When the two locomotives collided at nearly forty miles an hour, a Des Moines newspaper reported, they were “utterly demolished, rising to smite each other.”

“Thousands of people made a mad rush for the wreck and swarmed over it for relics.”

According to the newspaper, more than eighty thousand people witnessed the collision.

Joe Connolly was on his way.

He would later write: “I believed that somewhere in the makeup of every normal person there lurks the suppressed desire to smash things up. So I was convinced that thousands of others would be just as curious as I was to see what actually would take place when two speeding locomotives came together.”

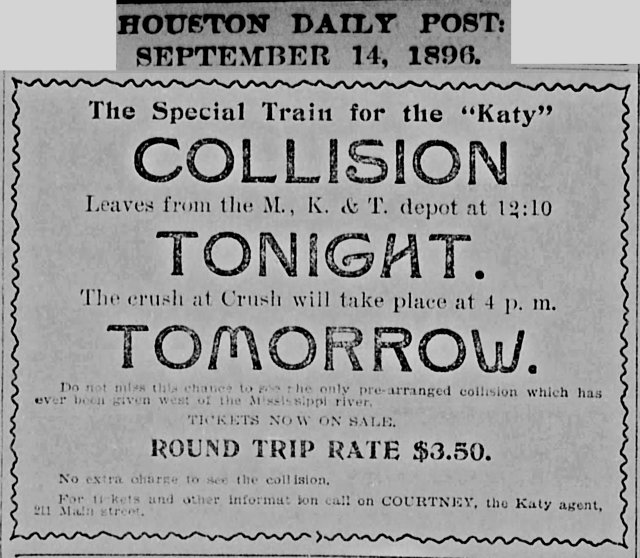

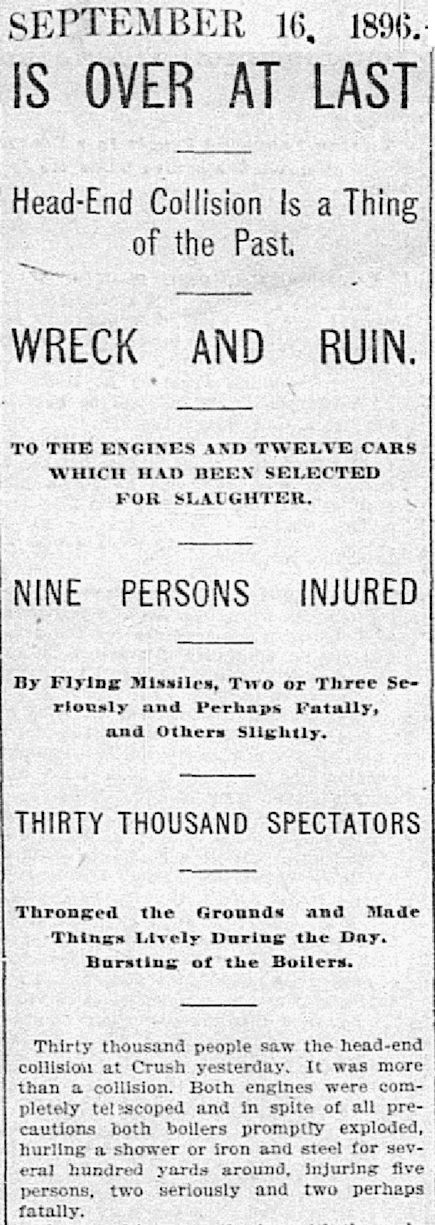

Just four days after Connolly’s first collision came the most famous staged locomotive collision of all.

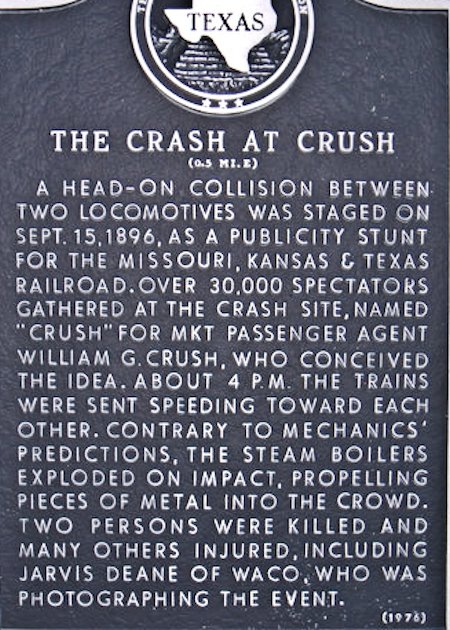

William George Crush, a passenger agent of the Missouri, Kansas & Texas (Katy) railroad, talked his superiors into letting him stage a locomotive collision as a publicity stunt promoting the Katy.

Outside Waco a temporary track was laid for two thirty-two-ton Katy locomotives. In fact, the site of the collision quickly grew into a temporary town: Two water wells were drilled. A circus tent from Ringling Brothers was erected. A grandstand, platform for reporters, two telegraph offices, and a temporary train depot were built. There were midway rides, carnival games, medicine shows, and lemonade stands and food vendors.

The “town” was called “Crush.”

The event was called the “Crash at Crush.”

To lure passengers/spectators to the Crash at Crush, the Katy railroad offered excursion trains—with reduced fares—from all over the state.

To lure passengers/spectators to the Crash at Crush, the Katy railroad offered excursion trains—with reduced fares—from all over the state.

On September 15, 1896 an estimated forty thousand people (for comparison, the population of Dallas in 1900 was forty-two thousand) gathered to gawk at Crush.

On September 15, 1896 an estimated forty thousand people (for comparison, the population of Dallas in 1900 was forty-two thousand) gathered to gawk at Crush.

One locomotive was painted red; the other, green. The locomotives were coupled to boxcars bearing large ads for the Katy, Ringling Brothers, and the Oriental Hotel of Dallas.

Just after 5 p.m. William George Crush, riding a white horse, threw down his white hat, signaling the engineers to put the two locomotives into motion.

The throng watched from what was thought to be a safe distance.

The Dallas Morning News reported: “The rumble of the two trains, faint and far off at first, but growing nearer and more distinct with each fleeting second, was like the gathering force of a cyclone. Nearer and nearer they came, the whistles of each blowing repeatedly and the torpedoes which had been placed on the track exploding in almost a continuous round like the rattle of musketry.

“They rolled down at a frightful rate of speed to within a quarter of a mile of each other. Nearer and nearer as they approached the fatal meeting place the rumbling increased, the roaring grew louder.”

The engineers bailed out.

At impact the two locomotives were traveling at about forty-five miles an hour.

The Morning News reported: “A crash, a sound of timbers rent and torn, and then a shower of splinters . . . There was just a swift instance of silence, and then as if controlled by a single impulse both boilers exploded [contrary to the assurances of Katy mechanics] simultaneously and the air was filled with flying missiles of iron and steel varying in size from a postage stamp to half of a driving wheel.”

Several spectators were severely injured.

Two were killed: Emma Frances Overstreet, the wife of a local farmer, was watching from a distance of one thousand feet when she was hit by debris. Ernest Barnell of Bremond, watching from a tree even farther away, was hit by debris.

The red-faced Katy railroad immediately fired William George Crush—and immediately rehired him after the railroad realized it was suffering no significant backlash from the tragedy. In fact, despite the two deaths and a few pesky lawsuits, the Crash at Crush was a PR success for the Katy.

The red-faced Katy railroad immediately fired William George Crush—and immediately rehired him after the railroad realized it was suffering no significant backlash from the tragedy. In fact, despite the two deaths and a few pesky lawsuits, the Crash at Crush was a PR success for the Katy.

A debacle that could have ended the nascent fad of locomotive collisions instead ensured the fad’s longevity.

Dozens of such collisions would be staged in the next forty years.

And Joseph Connolly would be among the most prominent promoters.

Connolly began to crisscross the country staging collisions from coast to coast. Connolly employed the same two engineers for years.

Sometimes he displayed advertising on the sides of the boxcars pulled by the two locomotives.

Sometimes he painted the names of political candidates and the terms of political issues on the sides of the two locomotives to give spectators incentive to root for one locomotive over the other.

According to biographer James J. Reisdorff, Connolly also used his theatrical savvy to spice up his spectacles, such as attaching dynamite to the front of the locomotives and filling boxcars with gasoline and smoldering charcoal so that the trains would be engulfed in flames upon impact.

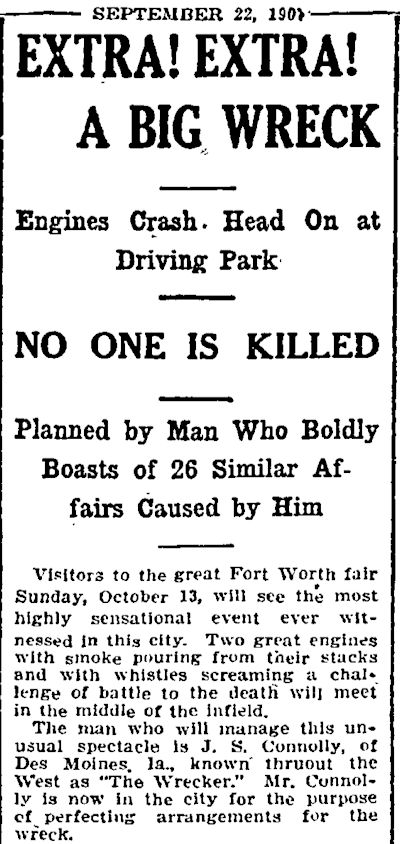

By the time Connolly rolled into Cowtown in 1907 he had staged twenty-six collisions and had earned the nicknames “Head-On Joe” and “the Wrecker.”

By the time Connolly rolled into Cowtown in 1907 he had staged twenty-six collisions and had earned the nicknames “Head-On Joe” and “the Wrecker.”

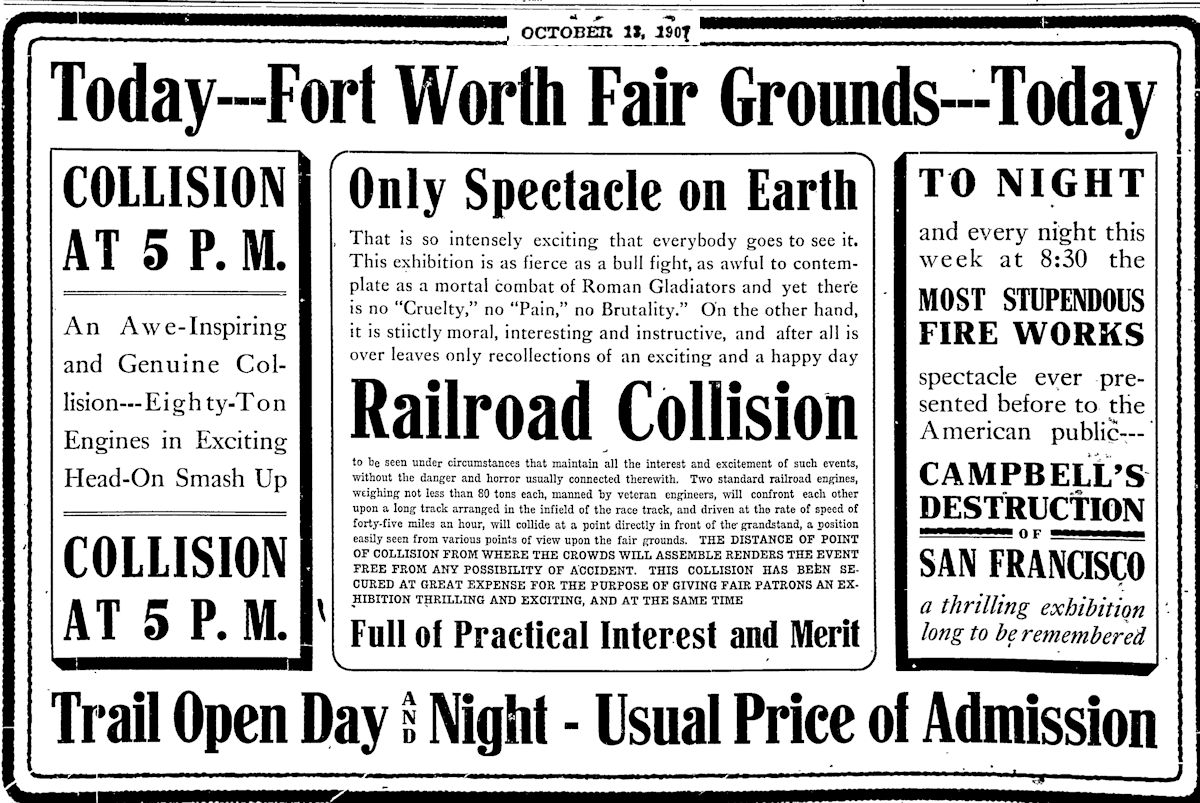

Connolly proposed staging a collision at the Fort Worth fair, held in October at the Driving Park west of downtown.

The fair was Fort Worth’s answer to the state fair in Dallas. Fort Worth’s fair included auto races, horse races, a fiddling contest, band concerts, a circus, a public wedding, and drills by the Fort Worth Fencibles militia unit.

Each day of the fair recognized a different group of people: employees of Fort Worth’s railroads and the interurban, Confederate veterans, and “old maids and old bachelors.”

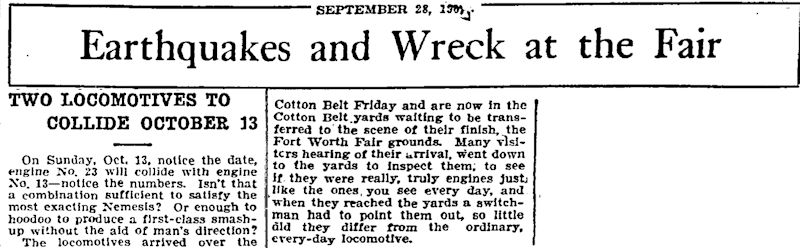

Before the fair began, Connolly’s two locomotives, which had been in passenger service in Ohio, had arrived from Cincinnati and were on display at the Cotton Belt yards near the power plant.

Before the fair began, Connolly’s two locomotives, which had been in passenger service in Ohio, had arrived from Cincinnati and were on display at the Cotton Belt yards near the power plant.

How did the two locomotives, weighing eighty tons each, get from the Cotton Belt yards to the Driving Park a mile and a half away? I do not know. The tracks of the Frisco railroad passed within five hundred feet of the Driving Park. Possibly the two locomotives were moved from the Cotton Belt yards to the Frisco track and then onto a temporary spur to the Driving Park.

The Ohio railroad had designated the two locomotives “No. 23” and “No. 133.” But then Connolly talked with No. 133’s last engineer.

“I’ll tell you, Mr. Connolly, that engine ought to be called 13 instead of 133. It’s the unluckiest affair ever put on eight wheels. Why, I’d made up my mind to quit the [rail]road if they didn’t give me a new engine.”

The engineer said No. 133 had killed fourteen people.

Upon hearing this, Connolly painted out the second 3 on the locomotive. No. 133 became No. 13.

The fair opened on October 8.

The fair opened on October 8.

Interest in the collision was keen.

Interest in the collision was keen.

In the days before the collision, a popular subject of debate was one of physics: What would happen to the two iron behemoths upon impact? There were three main possibilities:

- They would telescope horizontally.

- They would rise up from the front in an A shape.

- They would rise up from the rear in a V shape.

Another attraction of the fair was the “Destruction of San Francisco,” which simulated the earthquake of 1906.

Another attraction of the fair was the “Destruction of San Francisco,” which simulated the earthquake of 1906.

Something for everyone: Head-On Joe Connolly’s locomotive collision also was competing with a baby contest.

Something for everyone: Head-On Joe Connolly’s locomotive collision also was competing with a baby contest.

For the collision a temporary railroad track nearly a mile long was built at the fair ground, the Telegram reported. The track was laid out so that the two locomotives would crash into each other in front of the Driving Park’s grandstand.

For the collision a temporary railroad track nearly a mile long was built at the fair ground, the Telegram reported. The track was laid out so that the two locomotives would crash into each other in front of the Driving Park’s grandstand.

An ad in the Telegram declared: “This exhibition is as fierce as a bull fight, as awful to contemplate as a mortal combat of Roman Gladiators and yet there is no ‘Cruelty,’ no ‘Pain,’ no ‘Brutality.’ On the other hand, it is strictly moral, interesting and instructive, and after all is over leaves only recollections of an exciting and a happy day.”

On October 13 an estimated twenty-five thousand people turned out for the collision. The Telegram reported that “long trains from eleven trunk lines” brought people from out of town.

The Dallas Morning News reported, “A crowd estimated to number between 20,000 and 30,000 attended the Fair this afternoon to witness the head-on collision between two railway locomotives. The engines, Nos. 23 and 13, were started at either end of a . . . straight track and came together with a crush in front of the grandstand. . . . They were under full steam . . . when they came together and there was enough of realism about the mimic railway catastrophe to excite the crowd. After the locomotives had locked together in a death grip an immense cloud of smoke and escaping steam rolled up from the site, obscuring the wreckage. Small pieces of iron flew for a short distance in several directions, but as the crowd was some 500 feet away no one was injured. The engineers jumped in time to avoid the crash. The whistle of one of the locomotives, which had been left open, blew for thirty minutes after the crash came, and the sound emanating from the dense mass of smoke, steam, and dust produced a weird effect.

The Dallas Morning News reported, “A crowd estimated to number between 20,000 and 30,000 attended the Fair this afternoon to witness the head-on collision between two railway locomotives. The engines, Nos. 23 and 13, were started at either end of a . . . straight track and came together with a crush in front of the grandstand. . . . They were under full steam . . . when they came together and there was enough of realism about the mimic railway catastrophe to excite the crowd. After the locomotives had locked together in a death grip an immense cloud of smoke and escaping steam rolled up from the site, obscuring the wreckage. Small pieces of iron flew for a short distance in several directions, but as the crowd was some 500 feet away no one was injured. The engineers jumped in time to avoid the crash. The whistle of one of the locomotives, which had been left open, blew for thirty minutes after the crash came, and the sound emanating from the dense mass of smoke, steam, and dust produced a weird effect.

“Five thousand men and boys jumped the fences and made a rush for the wreckage after the collision to get a better view of the debris, and each time the boilers of the panting monsters showed signs of exploding the crowd would scatter. . . . At least one-third of those who saw the wreck were on the outside of the grounds. A railway embankment skirting the fair grounds was solidly packed for half a mile and every available tree, housetop, and telegraph pole affording a view was occupied.

“A freight train came along while this crowd on the embankment was waiting and stopped. Hundreds of men and boys climbed to the tops of the cars. The freight pulled out and got under headway so quickly that many of those on the cars were unable to alight and several hundred of these were taken to the railroad yards a mile and a half away, before the freight slowed up. This incident afforded great amusement to the occupants of the grandstand.”

The front page of the October 14 Telegram was a locomotive twofer: a photo of the collision and of a train bearing delegates of the Fort Worth Trades Excursion, which would visit seventy cities.

The front page of the October 14 Telegram was a locomotive twofer: a photo of the collision and of a train bearing delegates of the Fort Worth Trades Excursion, which would visit seventy cities.

Head-On Joe, his work here done, moved on. He staged another collision in San Antonio the next month.

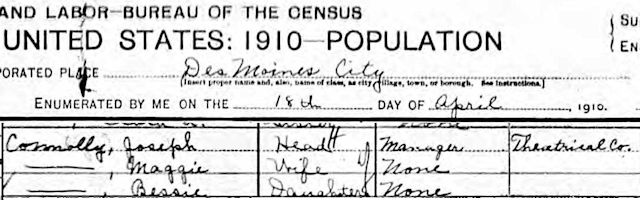

Joseph Connolly, who could claim one of the most unusual job titles in America, would continue to describe himself in prosaic terms: “amusement manager” and “manager” of a theatrical company.

Joseph Connolly, who could claim one of the most unusual job titles in America, would continue to describe himself in prosaic terms: “amusement manager” and “manager” of a theatrical company.

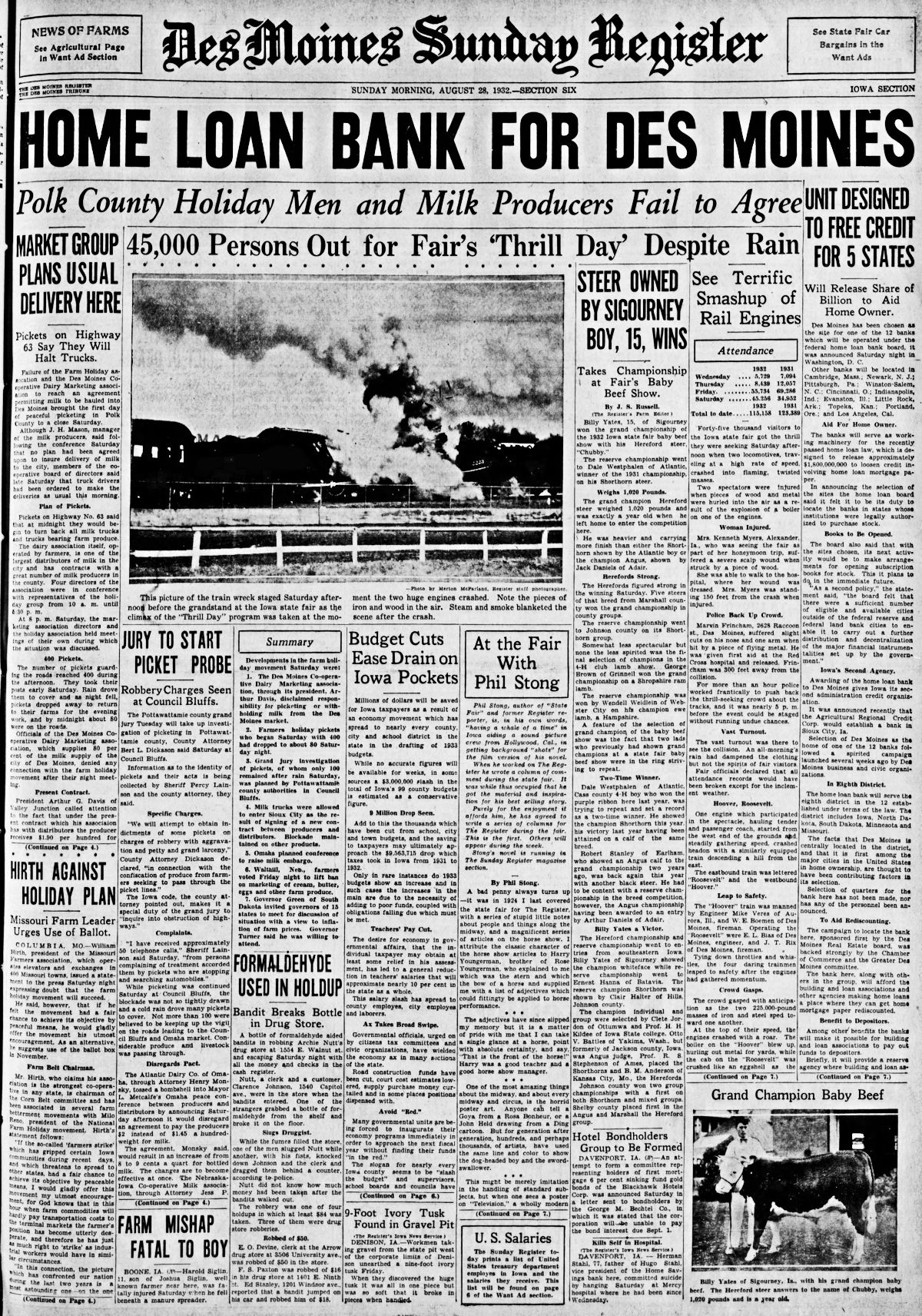

In 1932 Connolly staged his final collision, returning to where it had all begun for him thirty-six years earlier: the Iowa State Fair.

In 1932 Connolly staged his final collision, returning to where it had all begun for him thirty-six years earlier: the Iowa State Fair.

The year 1932 was an election year, and Head-On Joe’s finale had a political theme: The two locomotives were labeled “Hoover” and “Roosevelt.”

The engineers aboard the two iron surrogates tied down the throttles and whistles and bailed out before Hoover and Roosevelt smashed into each other on August 27 at almost fifty miles an hour, throwing metal and wood over a wide area.

Unlike the election in November, this Roosevelt-Hoover contest was a dead heat as Roosevelt burst into flame, and the fire spread to Hoover.

More than forty-five thousand people watched.

But by the 1930s staged locomotive collisions were losing their popularity. Amid the deprivations of the Great Depression, demolishing perfectly good locomotives seemed wasteful.

Another factor in the decline of the spectacle was changing times. By the 1930s the locomotive, once the symbol of power and speed, had been replaced in the public imagination by the airplane and the automobile. Daredevil pilots and drivers became all the rage at state fairs and other large public venues.

The last locomotive collision in America was staged in 1935.

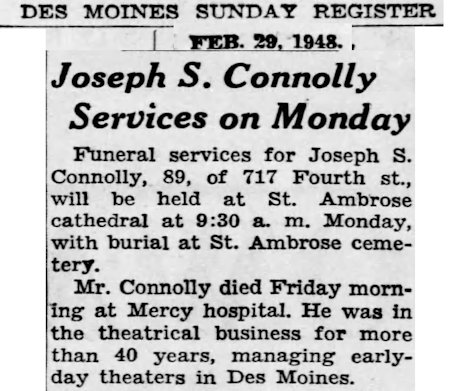

Joseph S. (“Head-On Joe”) Connolly died in 1948. His obituary in his hometown newspaper did not mention it, but from 1896 to 1932 Connolly had staged seventy-three collisions, destroyed 146 locomotives. He was proud that no one had ever been (seriously) injured at one of his spectacles.

Joseph S. (“Head-On Joe”) Connolly died in 1948. His obituary in his hometown newspaper did not mention it, but from 1896 to 1932 Connolly had staged seventy-three collisions, destroyed 146 locomotives. He was proud that no one had ever been (seriously) injured at one of his spectacles.

The Fort Worth collision probably looked a lot like this one in 1913:

(Thanks to Dennis Hogan for the tip.)

Posts About Trains and Trolleys

Your mention in this article of the Fort Worth Fencibles militia unit made me wonder if you have run across any accounts of muster days in Fort Worth.

Paul, a search of the archives for the terms “muster day/muster days” turns up nothing, which surprises me.

I have followed the “Crash at Crush” story for years. I’ve have never found where William George Crush was actually fired. Although it is suggested in many stories and is assumed that is what happened. Do you have any sources that concluded he was actually fired by the railroad? My accounts say he wasn’t. What say you?

Smithsonian Magazine and the websites wacohistory.org and mentalfloss.com say he was fired and rehired. Wikipedia also says he was fired and rehired, citing Bills, E. R. Texas Obscurities: Stories of the Peculiar, Exceptional & Nefarious. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2013.

Of course, some sources may be merely parroting other sources.