Let’s climb into the ol’ Retroplex Cruiser time machine once again and take a little spin back into the past. Buckle up while I punch in our destination and date: Fort Worth and 9 p.m. June 17, 1962.

That’s a short trip—just sixty-one years. Hang on . . . Mooz! (Mooz! is Zoom! backwards. Get it? Oh, never mind.)

Here we are: Fort Worth, June 17, 1962. According to the giant revolving clock atop the Continental National Bank building, the time is 9:02 p.m. I think we lost a couple of minutes due to turbulence as we passed through the Nixon administration.

As we hover over downtown, let’s get up to speed on what’s going on in the world in June 1962.

For starters Judgment at Nuremberg is showing at the Hollywood Theater. Popular songs on jukeboxes and car radios include “I Can’t Stop Loving You” by Ray Charles and “Palisades Park” by Freddy Cannon. Charles Hobbie on KFJZ and Kenny Sargent on KXOL are popular deejays. Among the prime time television programs are 77 Sunset Strip and Route 66.

Jack Nicklaus, twenty-two, has just won the U.S. Open golf tournament in a playoff with Arnold Palmer. In the American Association baseball league, the Dallas-Fort Worth Rangers are eight games out of first place.

More ominously, the New York Times is serializing Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring, documenting the adverse environmental effects of the indiscriminate use of pesticides. The Dow Jones industrial average has fallen 5.7 percent in the first six months of 1962. The activist organization Students for a Democratic Society has just completed its Port Huron Statement, a manifesto foreshadowing the cultural rifts that will define the decade. Ambassador John Kenneth Galbraith has just warned President Kennedy about U.S. involvement in Vietnam: “There is . . . danger we shall replace the French as the colonial force . . . and bleed as the French did.” And the Presidium of the Soviet Union has just approved Operation Anadyr to place nuclear missiles just ninety miles from Florida: The Cuban Missile Crisis is just four months in the future.

No sweat, Suzette.

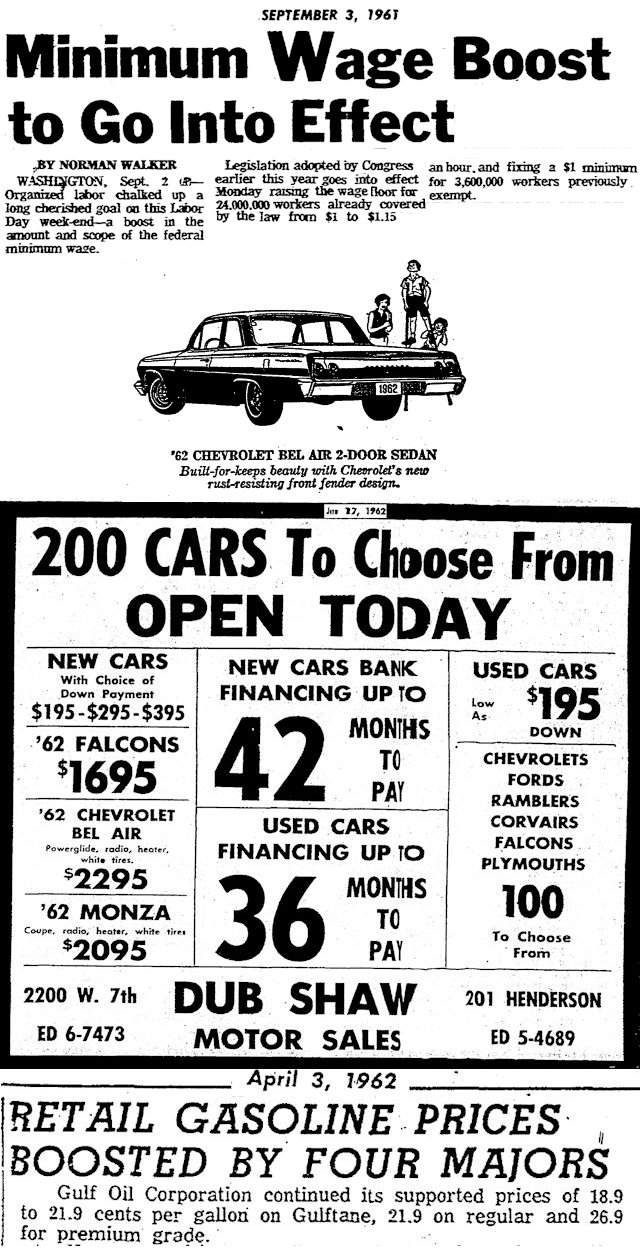

Because by June 17, 1962 the minimum wage has been raised to $1.15; on West 7th Street Dub Shaw will sell you a new Chevy Bel Air for $2,295 (with radio and heater!) or a new Ford Falcon for $1,695; at the corner Gulf station you can feed those beauties Gulftane for 18.9 cents a gallon. . . .

Because by June 17, 1962 the minimum wage has been raised to $1.15; on West 7th Street Dub Shaw will sell you a new Chevy Bel Air for $2,295 (with radio and heater!) or a new Ford Falcon for $1,695; at the corner Gulf station you can feed those beauties Gulftane for 18.9 cents a gallon. . . .

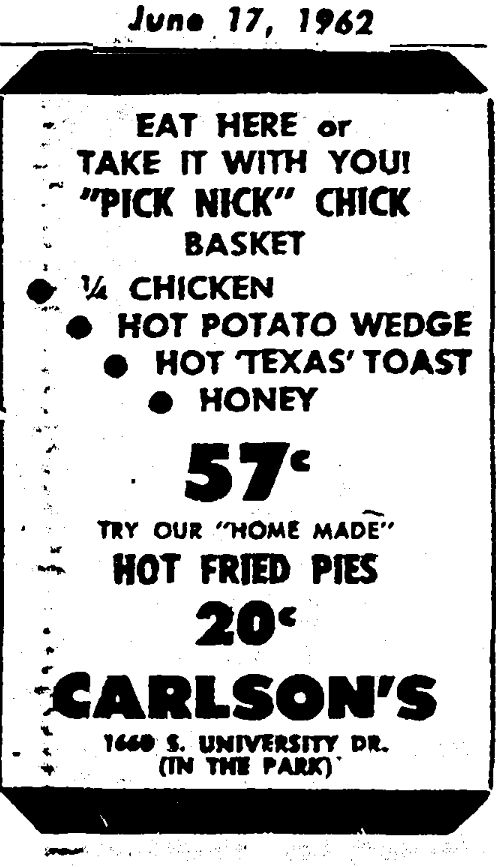

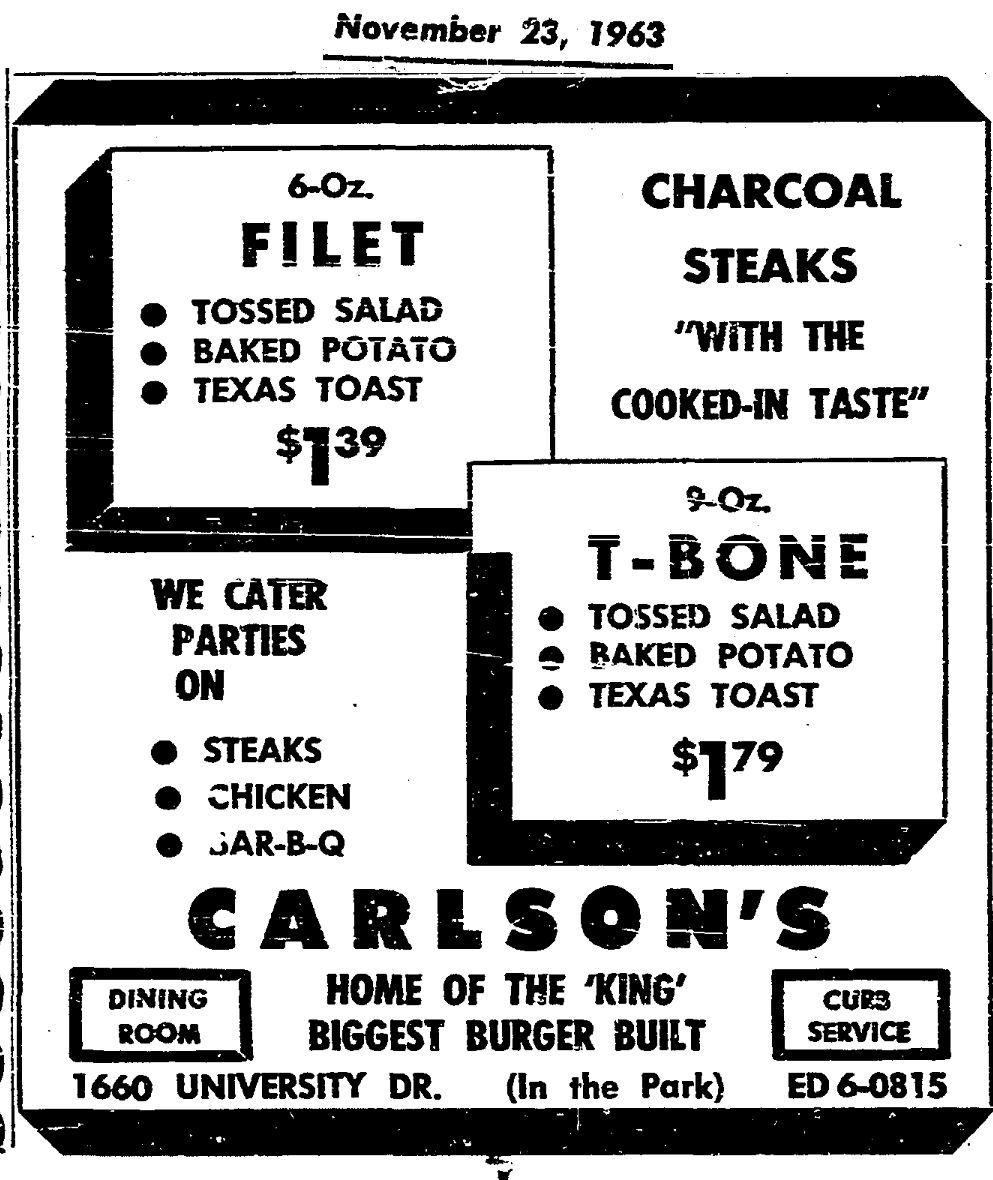

And at Carlson’s on South University Drive you can feed yourself for fifty-seven cents.

And at Carlson’s on South University Drive you can feed yourself for fifty-seven cents.

Life is good.

Let’s mooz over to Carlson’s and ease the Retroplex Cruiser into that parking space there between the cherry-red Merc coupe and the black-as-Satan’s-shadow ’40 Ford.

We’re here on a summer night, and the place is packed.

Carlson’s may be, to its owner, cooks, and carhops, to its creditors, its accountants, and others in the adult world, a business, specifically, a restaurant.

But to these teenagers around us Carlson’s tonight is no mere business. To these teenagers Carlson’s is an auto show, a fashion show, a trysting place, a clubhouse, a stage, a boxing ring, a sanctuary—a world away from the world.

Teenagers, especially students of Paschal High School and TCU, regard Carlson’s as the place to hang out, to see and be seen, to show off a new blouse or a new set of hubcaps, to meet friends, to fall in—and out of—love, to settle a score.

Oh, and if time allows, to eat a meal.

Carlson’s—even more than its Polytechnic counterpart, the Clover—is the most popular of Fort Worth’s drive-in restaurants during this, the golden age of motoring, when gas is cheap, cars are big, and teenagers as young as fourteen can get a driver’s license with a hardship waiver.

(And to a teenager, not having a driver’s license definitely qualifies as a hardship.)

For these teenagers a car is not merely a vehicle for getting from point A to point B. A car is essential for status, courtship, self-expression.

Carlson’s is a microcosm of teenage life—poodle skirts and fender skirts, ducktails and tail fins—and on display in this microcosm are all the attendant emotions of that tumultuous time of life: insecurity, bravado, infatuation, lust, jealousy, head-in-oven melancholy, head-in-clouds euphoria.

Carlson’s has a perfect location: University Drive is the West Side’s main drag from north to south (close to Forest Park, the West Freeway, TCU and Paschal, Casa Manana, Farrington Field, the Parkaire Drive-In Theater).

And, as you can see, Carlson’s also has a big parking lot.

This big parking lot is perfect for the teenage ritual of cruising. For teenagers of the West Side—and even an occasional errant teen from the East Side—cruising Carlson’s is a requisite part of a date night after a ball game or a movie or a dance.

Just watch. The ritual is almost hypnotic: a restless—but slow—bumper-to-bumper circling of souped-up, whitewalled, Turtle Waxed cars through the parking lot as drivers and passengers wave, point, preen, mug, flirt. Each car headlight shines like the lantern of a motorized Diogenes searching for . . . what?

Listen. Engines revving, horns honking, radios blaring, kids shouting, whistling, laughing.

Take a deep breath. Smell that? The night air is fragrant with a blend of Old Spice, Aqua Net, cigarettes, Clearasil, and Bardahl.

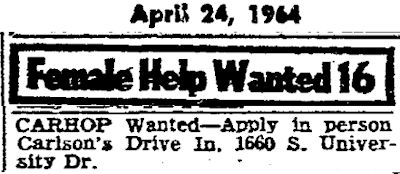

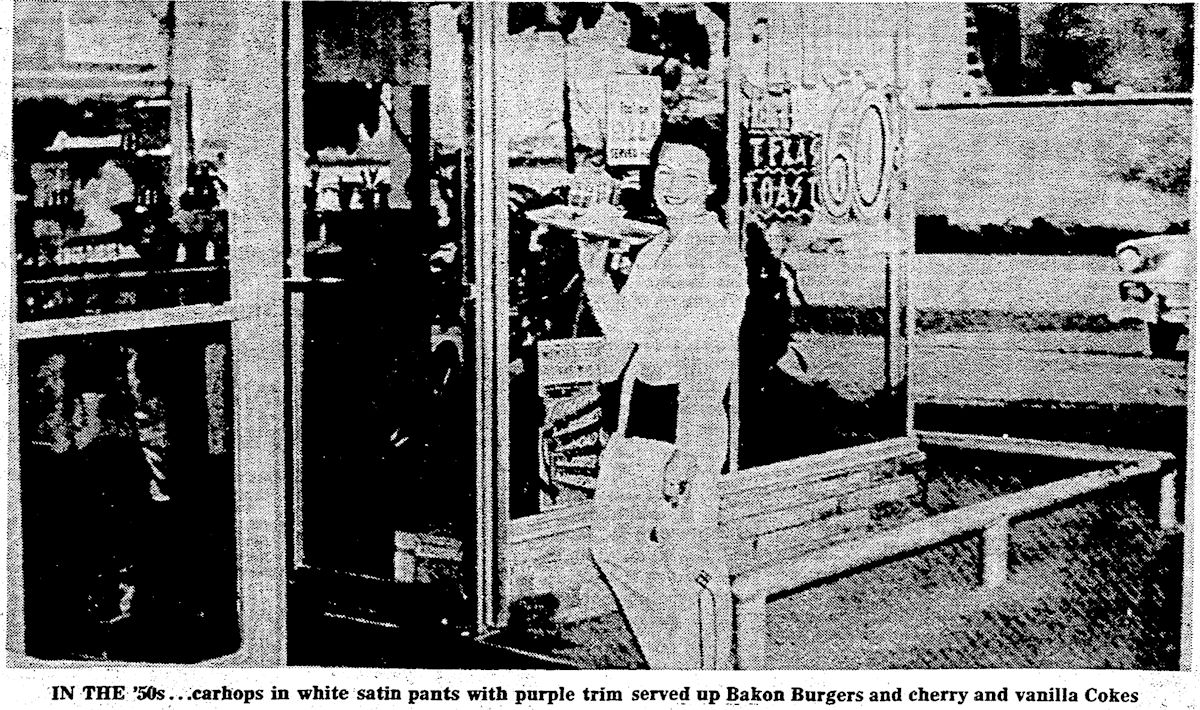

Deftly negotiating the procession of cruisers are Carlson’s carhops carrying their trays of food to car windows. Notice that the Carlson’s carhops are a bit older than the high school girls who work on roller skates at other drive-in restaurants. Most of Carlson’s carhops have husbands and children but nonetheless are young and engaging. In addition to delivering burgers and shakes to car windows, they soothe hurt feelings, play matchmaker, peacemaker, and even loan officer if a boy on a date is embarrassed by a shortage of funds.

Deftly negotiating the procession of cruisers are Carlson’s carhops carrying their trays of food to car windows. Notice that the Carlson’s carhops are a bit older than the high school girls who work on roller skates at other drive-in restaurants. Most of Carlson’s carhops have husbands and children but nonetheless are young and engaging. In addition to delivering burgers and shakes to car windows, they soothe hurt feelings, play matchmaker, peacemaker, and even loan officer if a boy on a date is embarrassed by a shortage of funds.

Among the orders those carhops are carrying are mugs of root beer, catfish baskets, “Pick Nick” Chick baskets, burgers and shakes, lime freezes, cherry and vanilla Cokes, chicken-fried steaks, barbecue, milkshakes and malts, potato wedges, banana splits.

Among the orders those carhops are carrying are mugs of root beer, catfish baskets, “Pick Nick” Chick baskets, burgers and shakes, lime freezes, cherry and vanilla Cokes, chicken-fried steaks, barbecue, milkshakes and malts, potato wedges, banana splits.

But Carlson’s signature dish is the Bakon Burger: a charbroiled cheeseburger topped with bacon and a secret barbecue sauce.

For teenagers Carlson’s is Teentown, an adult-free zone. Here there are no principals, no parents. The only authority figure is Sergeant Lawrence Wood, the storied Fort Worth police motorcycle officer.

Wood moonlights at Carlson’s, rumbling in on his Harley-Davidson at 9 p.m. each night to enforce a semblance of law and order on hundreds of hormonal teenagers. See him down there on our left? Looks like he’s writing up that kid in the De Soto Club Coupe with fuzzy dice, baby moons, and no taillights.

But Wood is generally liked by the Carlson’s crowd. He is firm but fair. He breaks up the occasional fight, pours underage drinkers’ beer down the gutter, issues the dreaded threat “Don’t make me call your ma,” or, if pushed, metes out the worst punishment of all: banishment from Carlson’s.

Lawrence Wood is the sheriff of Teentown.

(In November 1963 Wood will escort the Kennedys from and to Carswell Air Force Base.)

(In November 1963 Wood will escort the Kennedys from and to Carswell Air Force Base.)

At this point let’s freeze-frame the population of Teentown and its sheriff, crank up our Retroplex Cruiser time machine and lay rubber even further back in time: to 1914.

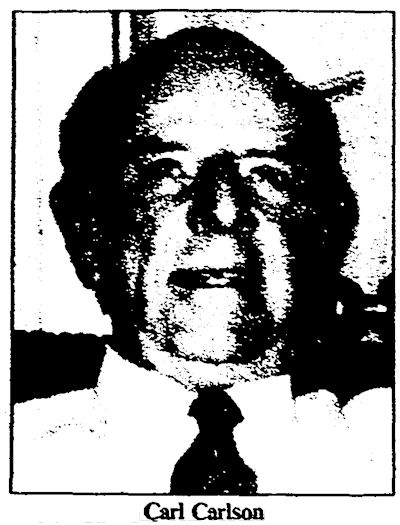

That’s when Carl Edward Carlson Jr. was born in the town of Carlson near Austin. The town was named for his grandfather, Pete Carlson, an early settler. The Carlson family moved to Fort Worth about 1925. Carl Jr. graduated from Central High School.

That’s when Carl Edward Carlson Jr. was born in the town of Carlson near Austin. The town was named for his grandfather, Pete Carlson, an early settler. The Carlson family moved to Fort Worth about 1925. Carl Jr. graduated from Central High School.

During World War II he was the executive officer of the general hospital at Camp Bowie—the one in Brownwood. After the war Carlson returned to Fort Worth.

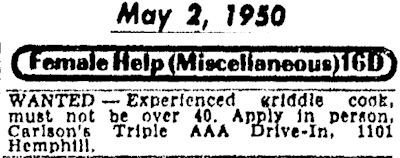

His first venture into the restaurant business was a hamburger-and-root beer stand at 1101 Hemphill at West Rosedale Street (a QuikTrip stands there today).

His first venture into the restaurant business was a hamburger-and-root beer stand at 1101 Hemphill at West Rosedale Street (a QuikTrip stands there today).

But Gulf Oil owned the property. When Gulf decided to build a service station on the property, Carlson had to relocate.

Best move he ever made.

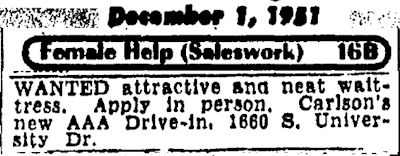

In 1951 at 1660 South University Drive Carlson opened his Carlson’s AAA Drive-In Restaurant.

In 1951 at 1660 South University Drive Carlson opened his Carlson’s AAA Drive-In Restaurant.

And an institution was born.

Thirty years later, in 1981, some of the old Carlson’s crowd shared their memories with the Star-Telegram.

The sheriff of Teentown, Lawrence Wood, recalled how boys he had banned from Carlson’s resorted to proxies:

“I told them they couldn’t come to Carlson’s for a week. Well, that meant these boys would send their girlfriends in after me. These little girls would come up and say, ‘Please, Sergeant Wood. We can’t come to Carlson’s if old Joe can’t come,’ and I’d say, ‘Well, you’d better get yourself a new boyfriend.’ But they’d stick after it and butter me up, and usually I’d get conned into letting ’em come back early.”

Wood recalled that years later he once appeared in court as a witness in a DWI case he had brought. He recognized the opposing attorneys as former Carlson’s regulars. During the trial a bitter argument developed between the two attorneys. The judge summoned them to his chamber. Wood stuck his head in the chamber door and said, “Now, boys, either you cut this out, or I’m gonna bar you both from Carlson’s for two weeks.”

That broke the tension between the two attorneys, and the trial continued more amicably.

Lou Hitt was a carhop. She worked at Carlson’s from 1958 until the restaurant closed.

“Oh, it was fun, a lot of fun,” she recalled.

Unlike the carhops at some drive-in restaurants, Hitt said, “We never wore skates, but we did have uniforms: white satin britches with purple stripes down the leg and white tops.”

(Carl Carlson knew on which side his Texas toast was buttered: Purple and white are the colors of both Paschal and TCU.)

Hitt recalled: “I imagine there were two hundred or three hundred cars on the lot if it was full. There were six carhops on the evening shift. We all got so we could take seven or eight trays out at once.”

Richard Campbell, Paschal 1950, was one of the thousands of teens who came of age at Carlson’s. He told the Star-Telegram: “We felt like bigtime Charlies driving in there in our own cars and everything. We felt like adults. But at the same time, it was a controlled situation. It was a good place for teenagers to go.”

Jean Roach, Paschal 1960, recalled: “It was a neat place to go because you knew you were always safe. I don’t think parents objected to us going because it was a good atmosphere. It was a good, clean, fun place to go, and I think Mr. Carlson’s rapport with the kids was why. Everybody respected him.”

Jim Marrs, Paschal 1962 and later a Star-Telegram writer and author of books about cover-ups and conspiracies, remembered the vague air of menace that teenage boys reveled in at Carlson’s:

“The main topic of discussion amongst all the guys that hung out at Carlson’s was what kinda rumble there might be that night with people from Poly or Arlington Heights. It was a ritual and usually a false alarm.

“At least once a night someone would screech in and yell, ‘There’s a bunch of guys from Poly over at the Clover who say we’re not tough unless we come over and see them.’ So we’d cruise over there, look around aggressively from our cars, then come back to Carlson’s and order a Coke and wait for the next false alarm.

“Occasionally it wasn’t a false alarm, but generally nothing much ever happened.

“Looking back on it now, those fights remind me of the young man initiation rites you read about in National Geographic. We’d strut around, flexing our muscles, bluffing.”

David “Smiley” Irvin, Paschal class of 1960 and later owner of Smiley’s Photography, recalled: “People would go down to Carlson’s to show off their cars, if they had one. I remember they’d roll down their windows, and guys would press their arms against the ledge to show off their muscles. Of course, I’d have to sit inside because I didn’t have any muscles.

“It was the fishbowl effect. Everybody there was on display. You’d drive around and around and around and around. More gas would be lost circling around Carlson’s than would be lost driving around town. In retrospect, it was crazy. You’d come in, drive around a few times, see who was there, and find you a place to pull in.

“If you saw someone you knew,” Irvin said, “you’d jump out and run over to their car before Sergeant Wood would see you because you weren’t supposed to do that. It was like a game of cat and mouse or musical cars.

“Another thing that happened, guys would start to rev their engines. If one guy started it, every guy started it. It was like a bunch of roosters. Of course, Sergeant Wood would get in a hissy and go around with his club thumping hoods. It was a game, a crazy, fun game.”

Other Carlson’s hijinks, the Star-Telegram wrote in 1981, included honking horns, especially by girls who belonged to social clubs that had their own coded honks; stuffing cars with as many passengers as possible; writing messages on fogged-up car windows; and waging a sudden assault on a car full of girls or wide-eyed freshmen. Such an assault often took the form of climbing onto the roof of a car, pressing teenaged noses against window glass, and other simian cavorting.

But a big change came to Carlson’s about 1962, the Star-Telegram wrote, when Carl Carlson erected barricades behind the restaurant to stop the unending circling of teenagers in cars. The ritual may have been sacrosanct to the cruisers, but it turned a parking lot into a circular parade route and was off-putting to adults who otherwise might spend money at Carlson’s.

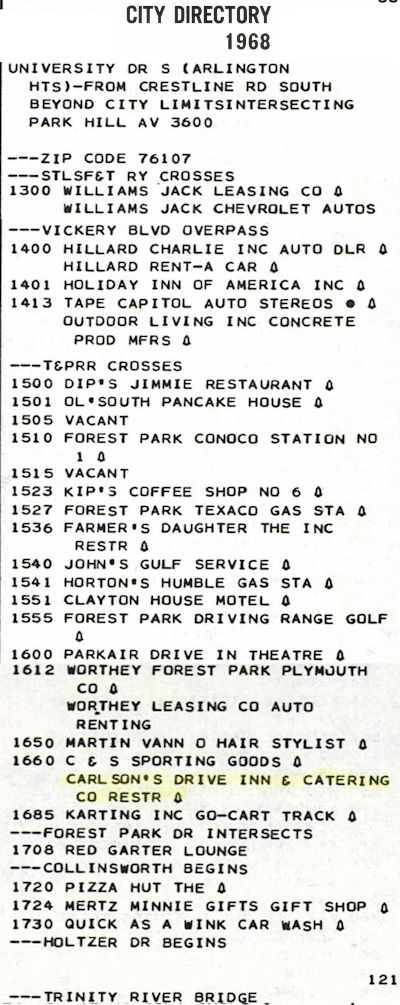

By 1968 University Drive between Forest Park and the river had developed, giving Carlson’s plenty of competition for the teenage dollar.

By 1968 University Drive between Forest Park and the river had developed, giving Carlson’s plenty of competition for the teenage dollar.

In 1970 came the biggest change of all: After nineteen years Carl Carlson converted his drive-in restaurant into an indoor restaurant. Carlson’s AAA Drive-In became Carlson’s 3Cs Restaurant.

The indoor version of Carlson’s appealed to older diners. Some of those older diners had been Carlson’s customers as teenagers. Now they were coming into the restaurant with teenagers of their own.

“We’ve had a lot of ’em bring their children in,” Carlson said. “One couple came by last year, they’d met at homecoming out there on the parking lot and got married. Their oldest kid was sixteen years old.”

Older diners had more money to spend than had the teenaged Coke-and-fries set: Carlson’s business quadrupled in the first year.

Carlson’s was changing, and the world around Carlson’s was changing. By 1970 many of the girls of Carlson’s drive-in days had traded poodle skirts for maternity dresses. Many of the boys had traded Bel Airs and Falcons for M48 tanks and armored personnel carriers and were cruising a new location: southeast Asia.

For some it would be their last ride.

On December 20, 1980 came the final change: Carl Carlson retired and closed his Carlson’s 3Cs Restaurant.

“Thirty years in the restaurant business is a long time,” he said in 1981.

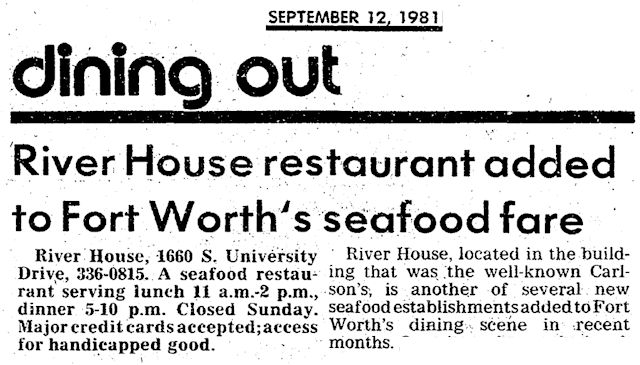

A seafood restaurant took over the Carlson’s building.

A seafood restaurant took over the Carlson’s building.

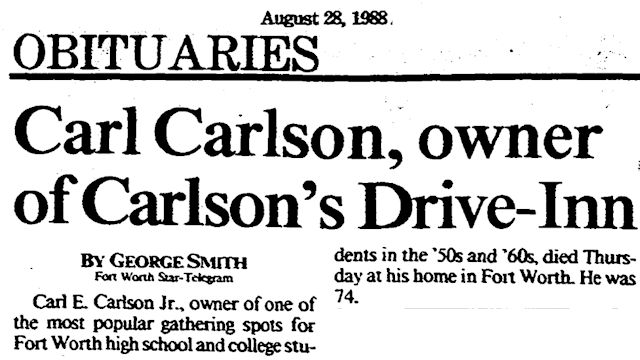

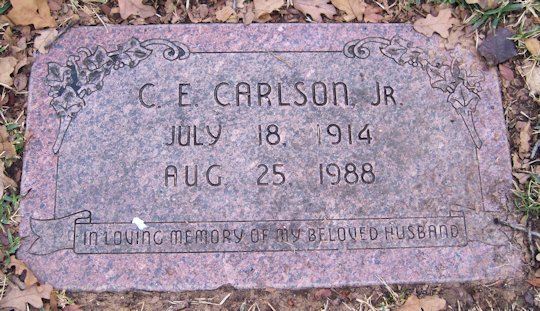

In 1988 Carl Edward Carlson Jr. died at age seventy-four.

In 1988 Carl Edward Carlson Jr. died at age seventy-four.

The man who gave teenagers a place to be teenagers is buried in Greenwood Cemetery.

The man who gave teenagers a place to be teenagers is buried in Greenwood Cemetery.

In 2001—fifty years after Carl Carlson opened his drive-in restaurant—a Staples store was built on the site.

(Thanks to Chris Murphy for the reminder.)

What did the Bacon Burger have on it?

Any veggies? What kind of cheese? Sauce?

I want to try to make it.

What memories. I met my true love there. My friends and I spent many nights cruisin there. All good clean fun.!we would also drive to the Clover in River oaks and Eastside… also the Lone Star drive-in restaurants. It was a revolving door all night. I made friends from all over FtWorth and 60 years later we are still in touch. I feel sorry for the generations since then that didn’t have that experience.i always knew it was a special time I was lucky to live in.

We have been crying since I started to read this. I read it out loud to my husband, who i met in Sept 1964. My friend Joan, drove me to Carlsons because I didn’t have a car. She set it up that Robert would come up to the car and meet me. Our first date was October 2, 1964. And the rest is history, as they say. We started “going steady”December 16, 1964. We got married June 15, 1969. We all loved Carlsons and feel so lucky it was part of our lives. Thank you so much for writing this incredible post.

Thanks for sharing. I starting working for Carl in 1972 at 16 years of age and worked for him for 5 years before departing for Sam Houston State University. I was the luckiest kid in Fort Worth, for I had two great fathers: My biological father, a great dad, and Carl who was my “dad” in the evening and on Sundays when we would work around the restaurant fixing and/or breaking things. He was a great friend, mentor, boss, and “dad”. I owe a lot of my success in life to Carl. He was one-of-a-kind!

I didn’t see any mention of Chuck Wagon, on Meadowbrook Drive, the Eastern Hills hangout.

And what, one might well ask, was a good ol’ Poly boy doing at an Eastern Hills hangout? No! Don’t tell me. Let us draw the veil of discretion over that dark passage in your ill-spent youth. Good to hear from you, Ken.

Loved the trip down memory lane. The Clover on Rosedale was our special place on the East side of Fort Worth after church on a Sunday night. I even remember that there was a Bensons’s drive-in there way before the Clover. Mom and Dad would take us there for burgers and fries on a Saturday night back in the 1940s. By 1962, I was already a Mom and lived at Abernathy, Texas out near Lubbock. There was a drive-in in Lubbock called the Hiddy-Ho that was the favorite place for teenagers, Texas Tech students and young adults on the prowl. Thanks, Mike for the memories.

Thanks, Janet. As an East Sider, I, too, remember the Clover far better than Carlson’s.

I remember I was in the first grade when my aunt would take me to see my beautiful mother who was a carhop for Carlsons. It was so much fun to get my burger with pickles only on it served on the car window tray. There was always a lot of action going on with cars going all about, and it so exciting. Lots of convertibles too. Everyone seemed happy, and the laughter going through the air was magical. Wow, those were definitely the good old days.

I remember Lou Hitt very well, I think her sister also worked at Carlson’s. Met my future husband after he returned from Vietnam at Carlson’s….. We would all chip in for gas, because we would line up on University and wait for our turn to cruise , wait even longer for a parking space. “I’ll have a Bakon Burger,a potato wedge and root beer in a frosted mug.” From Carlson’s we would head to the Lone Star Drive-In on Camp Bowie…then repeat the same rounds several times in a single night. I have a photograph of Carlson’s somewhere in “My Stuff”.

Happy Days. Change the “Carlson’s” references to “Clover,” and that was the East Side story.

Great trip! I remember many visits to Carlson’s. Root Beer & a bakon burger with fries. I had forgotten about the drive-in theater being that close! When I drove there I usually went to the Lone Star on Berry & then came up from the south & left the same direction. So many places to go, so little time. Luckily gas was cheap! Thanks for the memories!

Thanks. Many of us did not realize it then, but the Carlson’s/Clover era was a great time to be a teenager.

What a great article…I loved the years I cruised Carlson’s…..mid 60’s.

Thanks, John. Maybe I was there one night when you were-Poly kid looking suspiciously out of place.

Yup. Me and John Lunt used to make the ritual ‘Cruise to Carlson’s. We’d chat with Betty and Roxie the car hops, and hotrodders. Richard Sukup.